Leadership

The Theories of Leadership

Richard Olley

Introduction

Leadership theories have abounded since the first leadership theory was published by a historian, Thomas Carlyle, in 1840. Carlyle believed that “the history of the world is the biography of great men”; hence, the central position of this theory suggests that some people (e.g., men) are born to lead. Great leaders are therefore not made, as leadership qualities are innate. Of-course, there is very little evidence to underpin this theory, and it has little support in in our contemporary world. Since Carlyle’s first documented leadership theory, our understanding of the practice and purpose of leadership has evolved, and a range of other approaches have emerged. As leadership theory has evolved, we have come to understand that the development of the specific skills, knowledge, attributes, and abilities required for successful leadership can be learned and enhanced through training and personal growth for existing and emerging leaders.

The leadership literature contains many leadership attributes and behaviours, ranging from gender to generational perspectives. Undoubtedly, many leaders struggle with the notion that traditional leadership is about control, rules, regulations, and boundaries. In contrast, more contemporary leadership models emphasise freedom of thought, making room for creativity, valuing outcomes, welcoming new ideas, and focussing on the behaviours leaders exhibit toward their followership to create positive organisational outcomes.

Contemporary leadership thinking showcases leader behaviours, considering how leaders use personal influence to develop and inspire others in the organisation to develop and inspire people to achieve organisational goals, while also making a difference in the community being served. There is now a significant body of evidence in modern literature to support this contemporary leadership approach (Avolio, Bass, and Jung, 1999; George, 2004; George and Sims, 2007; George and Sims, 2007)

Before we discuss the literature on theories of leadership, what do you perceive as leadership?

Activity

Before progressing to the next section, take some time to document what you believe best describes leadership in the text box provided below (maximum of 100 words).

Your description does not need to be evidence-based, but should express what you consider to be the essential components of effective leadership.

Reflection

Leadership Theories

Leadership is an individual’s ability to influence, motivate, and enable others to contribute to the organisation’s effectiveness and success (House et al., 1999). Table 3.1, below, outlines the major leadership theories. Before examining the theory groups listed in Table 3.1, it must be made clear that the grouping framework developed to achieve this deliberately omits the Great Man Leadership Theory, as it does not drive the course of events in more contemporary knowledge (Mouton, 2017).

Grouping Framework for Leadership Theories

Table 3.1 shows the grouping framework developed by (Olley, 2021), summarises the more common theories, identifies notable researchers who have developed and explained the main theory concepts, and provides a broad development timeline.

Table 3.1. Grouping Framework for Leadership Theories (Adapted from Table 1 in Olley, 2021, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0)

| Theory Group | Explanation |

| Trait theories | Effective leaders share common personality characteristics known as traits (Stogdill, 1959). For those who subscribe to the Trait theory, effective leadership occurs when the traits of integrity, ethical decision-making, assertiveness, and compassion are evident (Bass and Stogdill, 1990). These traits are behaviours manifested because of the individual’s internal beliefs and processes necessary for effective leadership. These theories extend an early theory known as the Great Man Theory, asserting that individuals are born with or without the necessary leadership traits. |

| Behavioural/Motivational theories | Behavioural theories as the name suggests focus on how leaders behave and hope these behaviours can be copied by other leaders and thus created as leaders based on learned behaviours. Greenwood (1996) provides and excellent historical perspective on the the development of behavioural theories of leadership. These theories posit four types of leaders: autocratic, democratic, and passive-avoidant identified initially by Lewin and McGregor (McGregor, 1960) and more recently transformational. Other theories in this group include psychoanalytical theory of leadership, behaviourism, congitivism, ecological, humanism and evolutionary. |

| Contingency theories | Contingency theory emerged from growing evidence that there is no one correct leader type (Fiedler, 1967, Fiedler, 1971). These theories posit that leadership style is contingent upon the situation, the people, the task, the organisation, and other environmental variables. The Blake and Moutin Management Grid plots a manager’s or leader’s degree of task-centeredness versus their person-centeredness, and identifies five different combinations of the two and the leadership styles they produce (Molloy, 1998). |

| Power and influence theories | This theory group applies French & Raven’s Five Forms of Power (French and Raven, 1959). Theories that belong to this theory group highlight three forms of power; namely, legitimate, reward, and coercive power; and add two additional sources of power: expert power and referent power.Transformational and transactional leadership theories fit this group, and includes the laissez-faire style. Ethical leadership uses ethical concepts of situational ethics, cultural relativism, professional ethics, value-based ethics, rule-based ethics, and fairness-based ethics to manage subordinates (Brown et al., 2005). Ethical leadership is concerned with influencing people through the application of ethical principles (Brown and Treviño, 2006). The idea of authentic leadership is that leaders are seen as genuine and “real”. created this theory in his book Authentic Leadership, promoting leader behaviours that are transparent and ethical. Authentic leaders accept follower input and encourage the open sharing of information needed to make decisions. |

Activity

Write down what made them a successful leader in your eyes. Which of these attributes do you seek to incorporate into your leadership practice? In the square brackets following each behaviour listed below, rank each of the following leader attributes in their order of importance to you. The most important attribute is ranked 1, though the least important is ranked 7.

Perseverance [ ]

Honesty [ ]

Selflessness [ ]

Decisiveness [ ]

Trust [ ]

Integrity [ ]

Power and Influence Theories

A leader’s effectiveness comes from their ability to influence others at all levels of an organisation; hence, the ability to positively influence is an essential leadership skill. It is fundamental to success, providing the impetus for accomplishing team goals and fulfilling team responsibilities. Power and influence theories are therefore central to understanding contemporary leadership and have generated a broad body of knowledge discussed throughout this chapter.

Power and influence are deeply ingrained in human consciousness and fundamental social phenomena. Toffler (1992) argued that the human psyche is the product of power, and that fascination with power is the basis of politics (Warren, 1969). Organisational actors seek power to control and determine the future of organisations, the outcomes of interpersonal conflicts, and personal security perception in organisations (Kahn and Boulding, 1964). Hence, effective leadership requires a sound appreciation and understanding of power, and the ability to navigate and negotiate power in all circumstances.

Theories of power and influence take an entirely different approach to explaining leadership from those previously discussed. Rather than personality traits or environmental factors, these theories consider how leaders use power and influence to achieve the desired organisational outcomes.

These theories mostly examine the personal style of the leader. They include the full range leadership model of transactional and transformational approaches to leadership (Bass and Avolio, 1994). This theory group consists of the later-developed theories of authentic leadership (B. George, 2004) and ethical leadership (Brown Treviño, and Harrison, 2005). Bass and Avolio’s (1994) full-range leadership model includes three leadership styles transactional, transformational, and laissez-faire leadership.

Transactional Leadership

The transactional leadership style emphasises the importance of the relationship between the leader and followers. This theory focuses on mutual benefits derived from the ‘contract’ through which the leader delivers rewards or recognition in return for the followers’ service, commitment, and loyalty Bass and Avolio (1994), Weber (1947), (McCleskey, 2014)

According to transactional leadership theory, motivating and directing followers is primarily achieved by appealing to their self-interests (Avolio et al., 1999). Transactional leaders’ power comes from their position of authority and responsibility within the organisation. Transactional leadership achieves results by making the followers obey or comply with leaders instructions through a series of transactions and motivation is achieved by a system of leader-initiated reward and punishment (McCleskey, 2014). If a follower complies, a reward will follow. If the follower does not comply, punishment follows. Each transaction may involve observable dimensions between leader and follower, including:

- Contingent Rewards, in which transactional leaders link the goal to rewards, clarify expectations, provide necessary resources, set mutually agreed-upon goals, and offer various rewards for the successful performance of the task (Beauchamp, Welch, and Hulley, 2007).

- Active Management by Exception, in which the leader monitors team members’ work closely, looks for deviations from policy and procedure in work undertaken, and takes corrective action to prevent mistakes (Judge and Piccolo, 2004).

- Passive Management by Exception occurs when transactional leaders only intervene when unmet standards or performance are not expected (Doucet, Poitras, and Chênevert, 2009).

A leader who deploys a transactional leadership style subscribes to a strategy of granting rewards based on employee performance and functions in a heavily structured environment that encourages employees to achieve their best by applying workplace or team rules (Avolio, Bass, and Jung, 1999).

Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership theories, first described by Bass in 1985, assert that, unlike transactional leaders, transformational leaders inspire followers to abandon self-interest for the sake of the organisation. This approach has been found to have a profound impact on followers, with Bass (1985) noting a reduction in staff turnover, increased productivity, and higher staff satisfaction levels.

Transformational theories view the leader as a catalyst for a visionary approach while maintaining a strategic view of what needs doing. Transformational leaders value networking and collaboration (Bass and Avolio, 1994). These leaders are vigilant in their search for others who can demonstrate transformational leadership skills (Bass and Riggio, 2006). In terms of health and social care, the transformational leadership approach seems to have captured contemporary views on leadership. It appears to be the basis of the current industry-preferred leadership capability frameworks relating to health and aged care leadership (Australasian College of Health Services Management, 2017, Aged and Community Services Australia, 2014).

Transformational leadership theories posit that people are motivated by the task that they must perform. Those who practise transformational leadership emphasise cooperation and collective action, and individuals exist within the organisation or community context rather than in competition with each other (Bass, 2008).

Laissez-Faire Leadership

Laissez-faire leadership is a leadership style where leaders allow group members to make decisions with disengagement from the team, the organisation’s goals, and team members, expecting that they will solve problems themselves (Anbazhagan and R. Kotur, 2014). Laissez-faire leaders abrogate their responsibilities and avoid making decisions. As a result, the group can often lack direction.

Authentic and Ethical Leadership

Authentic leadership (B. George, 2004) and ethical leadership (Brown, Treviño, and Harrison, 2005) fit within the group power and influence theories and is complementary to the transactional and transformational leadership styles of the full-range leadership model (Avolio, Bass, and Jung, 1999), as they do not appear to be a subset of the full-range leadership model.

Authentic Leadership

Authentic leadership finds its conceptual roots in positive psychology, especially growth and self-fulfilment (Braun and Peus, 2016). Authentic leadership theory is a prominent and contemporary theory for which B. George (2004) is considered the primary theorist. This theory postulates that leadership is composed of four distinct components:

- Self-awareness (knowing oneself): A prerequisite is knowing one’s strengths, limitations, and values. Knowing what one stands for and what values are critical. Moreover, self-awareness is needed to develop other components of authentic leadership (George and Sims, 2007).

- Relational Transparency (being genuine): This involves being honest and straightforward in dealing with others (George and Sims (2007).

- Balanced Processing (being fair-minded): Authentic leaders consider views that are divergent from what is commonly held and consider all options on their merit before choosing a course of action. There are no impulsive actions or “hidden agendas”, and plans are well thought through and openly discussed (George, 2004).

- Internalised Moral Perspective (doing the ‘right thing’): An authentic leader has an ethical core. They know the right thing to do, driven by a concern for ethics and fairness (Walumbwa et al., 2011).

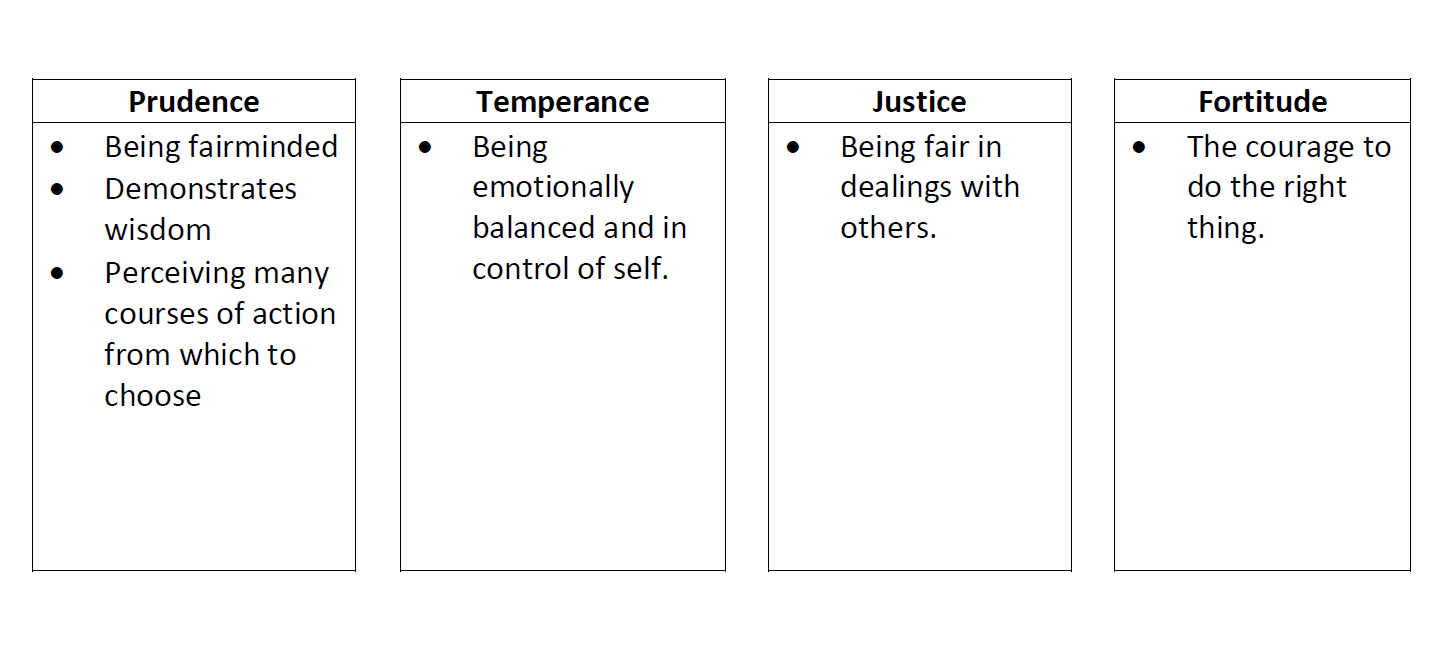

Self-reflection is common to authentic leaders who dare to do the right thing, even when a degree of selflessness or personal and organisational risk is required. Self-reflection is core to observing the roots of authentic leadership, which comes from ancient Greek philosophy that focuses on developing core or cardinal virtues (Gardner et al., 2011).

The Cardinal Qualities of Authentic Leaders

Authentic Leadership Theory has become popular as people search for leaders with previously defined qualities. George, (2004) asserted that authentic leaders demonstrate qualities of:

- understanding their purpose,

- practising solid values,

- establishing connected relationships, and

- demonstrating self-discipline.

George’s (2004) model focuses on the authentic leader’s different qualities and asserts that demonstrating these qualities or characteristics promotes the follower group to recognise they are an authentic leader. In response, their followers will display positivity and the organisation will benefit. Each of the qualities espoused by (W. George and Sims, 2007) is associated with an observable characteristic:

- Purpose and Passion: Authentic leaders display a sense of purpose to their follower group, knowing what is critical and the direction the follower group should take. The manifestation of purpose is passion (Iszatt‐White and Kempster, 2018). Passionate people are interested in what they are doing, are inspired and intrinsically motivated, and care about their work (Northouse, 2019). Authentic leadership occurs when individuals enact their true selves in their role as a leader (Leroy et al., 2012).

- Values and Behaviour: Those who practise authentic leadership have organisationally known values, know what they are, and do not compromise those values (B. George, 2004). This quality manifests itself through the leader’s behaviour, and authentic leaders act only according to their values.

- Relationships and Connectedness (Relational Transparency): The ability to build relationships with others and connect with their followers is also an attribute of authentic leaders who are willing to share their experiences, listen to others’ experiences, and communicate with their followers (Northouse, 2019).

- Self-discipline and Consistency: Self-discipline and consistency comprise the fourth dimension of authentic leadership. Self-discipline and consistency provide for leader focus and determination. Authentic leaders have a well-developed ability to focus on a goal and move forward towards that goal, even in the face of setbacks. Self-disciplined leaders remain cool, calm, and consistent during stressful situations (Northouse, 2019).

- Heart and Compassion: Importantly, leaders have “heart” and demonstrate this by showing their compassion. They are sensitive to others’ needs and are willing to help them (B. George, 2004; Northouse, 2019).

Acquiring these five dimensions of an authentic leader is not a sequential process; leaders develop continuously throughout their lives.

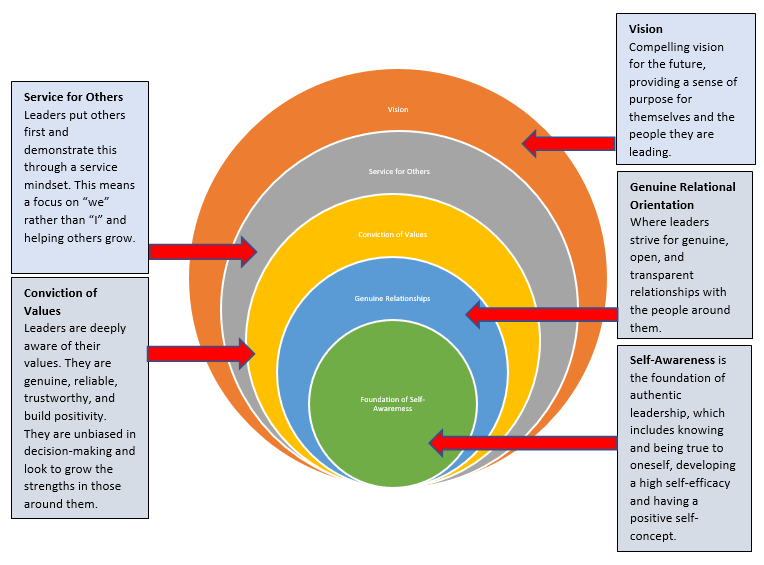

Dimensions of Authentic Leaders

Growing demand for increased transparency, integrity, and ethical behaviour within organisations has led to authentic leadership development (Gardner et al., 2011). Authentic leadership principles improve follower job satisfaction (Braun and Peus, 2016; Spence Laschinger and Fida, 2015). The figure below demonstrates the foundational relationship of self-awareness to the other attributes of authentic leaders.

The strengths of authentic leadership are that it fills a need for trustworthy leadership (Wang and Hsieh, 2013, Gill and Caza, 2015, Henley, 2018), and it provides broad guidelines for leaders with an explicit moral dimension (Sidani and Rowe, 2018). In turn, authentic leaders interact with their follower group in ways that build the team’s authentic leadership capacities, such as transparency, morality, ethical dealings, and future orientation (Avolio and Luthans, 2006, Luthans, 2003, Luthans, Norman, and Hughes 2006, May et al., 2003).

Luthans and Youssef (2016) described the emerging authentic leadership development literature succinctly:

Authentic Leadership Theory is grounded in postive psychology and has generated some criticisims; notably, that the focus on confidence, hope, optimism, and resilience, whilst important, cannot be considered in isolation from facing practical problems that require practical solutions. While there is ongoing research, it is not yet clear how authentic leadership leads to positive organisational outcomes (Breevaart et al., 2014), the moral elements of leadership, and their impact.

Authentic Leadership Theory is grounded in postive psychology and has generated some criticisims; notably, that the focus on confidence, hope, optimism, and resilience, whilst important, cannot be considered in isolation from facing practical problems that require practical solutions. While there is ongoing research, it is not yet clear how authentic leadership leads to positive organisational outcomes (Breevaart et al., 2014), the moral elements of leadership, and their impact.

Ethical Leadership

Leadership often requires decisions and deliberations that requires consideration from a moral or ethical perspective. These include allocating scarce resources, colleague and workforce issues, meeting performance targets, improving organisational culture, disclosure responsibilities, and transparency to identify errors or misadventures. At their core, decisions we describe as ‘ethical’ have a dimension of power use or abuse, values alignment or dissonance, and the creation of prevention of harm. In other words, most decisions in health care have an ethical dimension. While this list of ethical decisions is not exhaustive, the decisions made for these crucial areas in any organisation mean that ethical leadership has increasingly become an important theory of leadership. This is a complex area of leadership theory, as ethics is a pluralistic discipline, with Beauchamp and Childress (2001, p1) describing it as “a generic term for various ways of understanding and examining moral life”. Ethical leadership therefore draws on multiple ethical theories to equip leaders in navigating the moral dimensions of their leadership through various lenses to arrive at a well-considered decision. Importantly, ethical leadership requires that leaders consistently act and ethically lead, whether it is apparent to the follower group or not, and that the leader’s actions are consistent and within an ethical framework integrated into everyday leadership practice.

Ethical leadership draws upon concepts of:

- Situational ethics, where the ‘right’ action is dependent on the context of the situation (Fletcher, 1966).

- Cultural relativism determines what is ‘right’, noting the potential for harm in judging other cultures based on one’s own culture (Herskovits and Herskovits, 1972).

- Professional ethics considers that what is right is determined by a code of ethics of a specific profession that people in the profession should follow (Dinovitzer, Gunz, and Gunz, 2015).

- Value-based ethics is where a person’s values should guide their behaviour (Fusco, 2018).

- Rule-based ethics is where the rules of a specific group or organisation determine what is right, including society’s rules, religious rules, and an organisation’s rules (Fusco, 2018),

- Fairness-based ethics is a core issue of stakeholder theory in which fairness determines the ‘right’ actions and behaviours requiring fair and equal treatment of everyone (Hayibor, 2015).

While each of these elements are present in ethical decision making, ethical leadership practice requires an approach of seeing, valuing, and incorporating competing ethical interests. Ethical leaders foster trust and they value the maintenance of good relationships, provide a balance between the well-being of the followers, the wider community. Modern ethical leadership theory emphasises service in that the leader is a ‘servant’ of their followers. This understanding of leadership emerged from Greenleaf’s (1991) concept of servant leadership, which postulated that service to others is a leader’s primary concern. Recent literature has made similar claims (Wright and Quick, 2011, Sharma. Agrawal, and Khandelwal, 2019).

Ethical leadership is associated with authentic leadership, with May et al. (2003) linking authentic leadership, ethical decision-making, and positive organisational behaviour to develop a decision-making model to understand how authentic leaders make morally appropriate decisions. In organisations, ethical leadership centres around respect for others’ ethics, values, rights, and dignity and the leader’s honesty, integrity, trust, and fairness in leadership practice. Leaders demonstrate respect for ethical beliefs and values and maintain others’ dignity and rights, leading by values, vision, voice, and virtue (Brown and Treviño, 2006).

One model that may help structure ethical thinking for leaders is the 4-V Model (Center for Ethical Leadership, 2014). This model invites leaders to think about four aspects of leadership (virtues, values, vision, and voice) and align internal beliefs and values with external behaviours to pursue the common good as they apply in a particular context. The 4-V Model has four elements, with virtue being the centrepiece achieved by values, vision, and voice, and is related to trust, honesty, consideration, and charisma, as shown in this figure.

Considerable discussion continues about high profile ethical failures in leadership across a range of settings, resulting in increased interest in promoting ethical leadership (Den Hartog, 2015, Keselman, 2012, Brown and Treviño, 2006) organisational ethics, organisational behaviour, and organisational psychology to better understand how to promote ethical leadership (Den Hartog, 2015).

Unethical leadership may lead to follower disappointment and distrust, leading to a lack of interest and commitment, negatively impacting patient outcomes and organisational effectiveness (Keselman, 2012). Schaubroeck et al. (2012) examined how leadership and culture relate to followers’ ethical thinking and behaviours, and found that ethical leaders embed shared understanding through influencing ethical culture in follower teams and they positively influence followers’ ethical cognition, behaviour, and performance. Mayer et al. (2012) described similar findings, and demonstrated that employees are less likely to engage in unethical behaviour when the leader models desired ethical behaviours. Ethical leaders have less relationship conflict with co-workers, with Mayer et al. ( 2012) concluding that reinforcing leaders’ moral identities may promote ethical behaviours at several organisational levels. Ethical leadership is based on trust, respect, integrity, honesty, fairness, and justice, and promotes positive relationships. Research into the intersection of ethics and leadership remains mostly unexplored, and there are opportunities for further research and leadership practice development (Brown, Treviño, and Harrison, 2005).

Leadership theories such as transformational leadership and authentic leadership overlap with ethical leadership (Brown and Treviño, 2006). They are all ethically principled, share a social motivation, and require an engaging leadership style. Each of these approaches is associated with positive results in organisational commitment from nurses (Lotfi et al., 2018), increasing the retention of the healthcare workforce (Ibrahim, Mayende, and Topa, 2018), engagement of employees (Lahey, Pepe, and Nelson, 2017, Engelbrecht, Heine, and Mahembe, 2014), and the development of trust in the workplace (Engelbrecht, Heine, and Mahembe, 2014).

Activity

We now ask you to revisit what you thought about the person you considered the most successful leader from whom you would like to model their leadership practice earlier in the chapter.

Make any changes in the ranking based on what you have learned in this chapter.

Remember, the most important attribute is ranked 1; the least important is ranked 7.

Willingness to Listen [ ]

Perseverance [ ]

Honesty [ ]

Selflessness [ ]

Decisiveness [ ]

Trust [ ]

Integrity [ ]

Activity

Take some time to document what you believe best describes leadership (maximum of 100 words).

Your description does not need to be evidence-based, but should express what you consider to be the essential components of effective leadership.

Reflection

Revisit your description of what leadership is to you and record any differences to that description based on what you have learned in this chapter.

Key Takeaways

- There is no clear consensus on a definition of leadership.

- There is general agreement that leaders set direction and help themselves and others to do the right thing to move forward.

- Leaders achieve this by creating a vision and motivating and inspiring others to reach that vision. They also manage the delivery of the vision, either directly or indirectly, and build and coach their teams to make them stronger.

- Effective leadership is about all of this – and it’s exciting to be part of this journey!

References

Australasian College of Health Services Management. 2017. Master Health Service Management Competency Framework: ACHSM [Online]. Available: https://achsm.org.au/education/competency-framework [Accessed 7/11/2022 2022].

Aged and Community Services Australia. 2014. Australian Aged are Leadership Capability Framework. Available: https://acsa.asn.au/getmedia/56d9c659-72c7-4ac4-a26c-a33f8530cae6/Aged-Care-Leadership-Capability-Framework-2014#:~:text=The%20Aged%20Care%20Leadership%20Capability,%2C%20Purpose%2C%20Business%20and%20Change. [Accessed 27/12/2020].

Anbazhagan, S. and R. Kotur, B. 2014. Worker Productivity, Leadership Style Relationship. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 16, 62-70.

Avolio, B. J., Bass, B. M. and Jung, D. I. 1999. Re-examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the Multifactor Leadership. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72, 441-462.

Avolio, B. J. and Luthans, F. 2006. The high impact leader: moments matter in accelerating authentic leadership development, New York, McGraw Hill.

Bass, B. M. 1985. Leadership: Good, better, best. Organizational Dynamics, 13(3), pp.26-40.

Bass, B. 2008. The Bass handbook of leadership : theory, research, and managerial applications / Bernard M. Bass with Ruth Bass, New York, Free Press.

Bass, B. and Avolio, B. 1994. Improving Organizational Effectiveness through Transformational Leadership., Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications.

Bass, B. and Riggio, R. 2006. Transformational leadership, Mahwah, N.J, L. Erlbaum Associates.

Bass, B. M. and Stogdill, R. M. 1990. Bass and Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications, Simon and Schuster.

Beauchamp, T. L. and Childress, J. F. 2001. Principles of biomedical ethics. Oxford University Press, USA.

Beauchamp, M. R., Welch, A. S. and Hulley, A. J. 2007. Transformational and transactional leadership and exercise-related self-efficacy: an exploratory study. J Health Psychol, 12, 83-8.

Braun, S. and Peus, C. 2016. Crossover of Work–Life Balance Perceptions: Does Authentic Leadership Matter? Journal of Business Ethics, 149, 875-893.

Breevaart, K., Bakker, A., Hetland, J., Demerouti, E., Olsen, O. K. and Espevik, R. 2014. Daily transactional and transformational leadership and daily employee engagement. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87, 138-157.

Brown, M. E. and Treviño, L. K. 2006. Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17, 595-616.

Brown, M., Treviño, L. and Harrison, D. 2005. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 97, 117-134.

Center for Ethical Leadership. 2014. Ethical Leadership [Online]. Available: https://www.ethicalleadership.org/concepts-and-philosophies.html [Accessed].

Den Hartog, D. N. 2015. Ethical Leadership. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2, 409-434.

Dinovitzer, R., Gunz, H. and Gunz, S. 2015. Professional Ethics: Origins, Applications, and Developments. Oxford University Press.

Doucet, O., Poitras, J. and Chênevert, D. 2009. The impacts of leadership on workplace conflicts. International Journal of Conflict Management, 20, 340-354.

Engelbrecht, A. S., Heine, G. and Mahembe, B. 2014. The influence of ethical leadership on trust and work engagement: An exploratory study. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 40, 1-e9.

Fiedler, F. 1967. A theory of leadership Effectiveness, New York, McGraw-Hill.

Fiedler, F. 1971. Validation and extension of the contingency model of leadership effectiveness: A review of empirical findings. Psychological Bulletin, 76, 128-148.

Fletcher, J. F. 1966. Situation ethics: the new morality, New York, Westminster Press.

French, J. and Raven, B. 1959. The Basis of Social Power in Cartwright, D. (Ed.), Studies in Social Power, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press.

Fusco, T. 2018. Ethics, morals and values in Authentic Leadership. An Evidence-based Approach to Authentic Leadership Development. 1 ed.: Routledge.

Gardner, W. L., Cogliser, C. C., Davis, K. M. and Dickens, M. P. 2011. Authentic leadership: A review of the literature and research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 22, 1120-1145.

George, B. 2004. Authentic Leadership: Rediscovering the Secrets to Creating Lasting Value, New York, NY, Jossey-Bass [Imprint].

George, B. and Sims, P. 2007. True north: discover your authentic leadership, San Francisco, CA, Jossey-Bass.

George, B., Sims, P., Mclean, A. N. and Mayer, D. 2007. Discovering your authentic leadership. Harv Bus Rev, 85, 129-30, 132-8, 157.

George, W. 2004. Authentic Leadership: Rediscovering the Secrets to Creating Lasting Value, New York, NY, Jossey-Bass [Imprint].

George, W. and Sims, P. 2007. True north: discover your authentic leadership, San Francisco, CA, Jossey-Bass.

Gill, C. and Caza, A. 2015. An Investigation of Authentic Leadership’s Individual and Group Influences on Follower Responses. Journal of Management, 44, 530-554.

Greenleaf, R. K. 1991. Servant leadership: a journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness, New York, Paulist Press.

Greenwood, R. 1996. Leadership Theory: A historical look at its evolution. The Journal of Leadreship Studies, 3-16, 3.

Hayibor, S. 2015. Is Fair Treatment Enough? Augmenting the Fairness-Based Perspective on Stakeholder Behaviour. Journal of Business Ethics, 140, 43-64.

Henley, A. J. 2018. The Relationship Between Trustworthiness and Authentic Leadership. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Herskovits, M. J. and Herskovits, F. 1972. Cultural relativism: perspectives in cultural pluralism, New York, Random House.

House, R., Hanges, P., Ruiz-Quintanilla, S., Dickson, M. and Gupta, V. 1999. Cultural influences on leadership and organisations: Project globe. In: MOBLEY, W. (ed.) Advances in global leadership. Stamford: JAI Press.

Ibrahim, A. M., Mayende, S. T. and Topa, G. 2018. Ethical leadership and staff retention in Uganda’s health care sector: The mediating effect of job resources. Cogent Psychology, 5, 1-19.

Iszatt‐White, M. and Kempster, S. 2018. Authentic Leadership: Getting Back to the Roots of the ‘Root Construct’? International Journal of Management Reviews, 21, 356-369.

Judge, T. A. and Piccolo, R. F. 2004. Transformational and transactional leadership: a meta-analytic test of their relative validity. J Appl Psychol, 89, 755-68.

Kahn, R. L. and Boulding, E. 1964. Power and conflict in organizations, New York, Basic Books.

Keselman, D. 2012. Ethical leadership. Holist Nurs Pract, 26, 259-61.

Lahey, T., Pepe, J. and Nelson, W. 2017. Principles of Ethical Leadership Illustrated by Institutional Management of Prion Contamination of Neurosurgical Instruments. Camb Q Healthc Ethics, 26, 173-179.

Leroy, H., Anseel, F., Gardner, W. L. and Sels, L. 2012. Authentic Leadership, Authentic Followership, Basic Need Satisfaction, and Work Role Performance. Journal of Management, 41, 1677-1697.

Lotfi, Z., Atashzadeh-Shoorideh, F., Mohtashami, J. and Nasiri, M. 2018. Relationship between ethical leadership and organisational commitment of nurses with perception of patient safety culture. J Nurs Manag, 26, 726-734.

Luthans, F. 2003. Positive organizational behavior (POB): Implications for leadership and HR development and motivation, New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Luthans, F., Norman, S. M., and Hughes, L. 2006. Authentic leadership. In R. Burke and C. Cooper (Eds.), London: Routledge, Taylor and Francis.

Luthans, F. and Youssef, C. M. 2016. Emerging Positive Organizational Behavior. Journal of Management, 33, 321-349.

May, D. R., Chan, A. Y. L., Hodges, T. D. and Avolio, B. J. 2003. Developing the Moral Component of Authentic Leadership. Organizational Dynamics, 32, 247-260.

Mayer, D. M., Aquino, K., Greenbaum, R. L. and Kuenzi, M. 2012. Who Displays Ethical Leadership, and Why Does It Matter? An Examination of Antecedents and Consequences of Ethical Leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 151-171.

McCleskey, J. 2014. Situational, Transformational, and Transactional Leadership and Leadership Development. Journal of Business Studies Quarterly, 5, 117.

McGregor, D. 1960. Theory X and theory Y. Organization Theory, 358, 5.

Molloy, P. L. 1998. A review of the managerial grid model of leadership and its role as a model of leadership culture. Aquarius Consulting, 31, 2-31.

Mouton, N. 2017. A literary perspective on the limits of leadership: Tolstoy’s critique of the great man theory. Leadership, 15, 81-102.

Northouse, P. G. 2019. Leadership: theory and practice, Thousand Oaks, California, SAGE Publications, Inc.

Olley, R. 2021. A Focussed Literature Review of Power and Influence Leadership Theories. Asia Pacific Journal of Health Management, 16, 7-15 .https://doi.org/10.24083/apjhm.v16i2.807

Schaubroeck, J. M., Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., Kozlowski, S. W. J., Lord, R. G., Treviño, L. K., Dimotakis, N. and Peng, A. C. 2012. Embedding Ethical Leadership within and across Organization Levels. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 1053-1078.

Sharma, A., Agrawal, R. and Khandelwal, U. 2019. Developing ethical leadership for business organizations. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 40, 712-734.

Sidani, Y. M. and Rowe, W. G. 2018. A reconceptualization of authentic leadership: Leader legitimation via follower-centered assessment of the moral dimension. The Leadership Quarterly, 29, 623-636.

Stogdill, R. M. 1959. Individual behavior and group achievement: a theory : the experimental evidence, New York, Oxford University Press.

Toffler, A. 1992. Powershift. Revista de Filosofía, 175-178.

Walumbwa, F. O., Mayer, D. M., Wang, P., Wang, H., Workman, K. and Christensen, A. L. 2011. Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: The roles of leader–member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115, 204-213.

Wang, D.-S. and Hsieh, C.-C. 2013. The effect of authentic leadership on employee trust and employee engagement. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 41, 613-624.

Warren, D. I. 1969. The effects of power bases and peer groups on conformity in formal organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 544-556.

Weber, M. 1947. The theory of social and economic organization (T. Parsons Translation), New York NY, Free Press.

Wright, T. A. and Quick, J. C. 2011. The role of character in ethical leadership research. The Leadership Quarterly, 22, 975-978.