3 Co-Produced Best Practice Principles for Working with People Experiencing Long COVID

By Danielle Hitch & Sara Holton

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter and completing the learning activities, you will:

- Reflect on your current assumptions about what constitutes ‘best care’ for people with Long COVID.

- Review the concepts of ‘best care’ and ‘best care practices’ more broadly, including the tools available to translate them into practice.

- Self-assess your current approach to partnering with people experiencing Long COVID.

- Understand the co-design process used to develop best care principles for people with Long COVID.

- Identify and describe seven best practice principles in both plain language and clinical or professional terms.

- Complete an Action Plan to make improvements on working with people with Long COVID

- Translate your new knowledge about ‘best care’ to two personas and examine factors which influence individuals outcomes.

Introduction

Health professional and other caregiver (such as family) generally want to provide the best care possible to every person with Long COVID. In some practice areas, there are clear guidelines about best care practices built on an established evidence base – we know what works, for whom and in what circumstances. Sadly, that isn’t the case regarding recovery from COVID-19 infection and Long COVID at the moment. As stated in the previous chapter, “we are currently building the plane while flying it”.

This chapter provides an overview of best care and best care practices for people with Long COVID in healthcare. The co-design process employed to develop best care principles for people with Long COVID is then described in detail to provide a template for other services wishing to do the same with their local communities. A key output of this process was seven best practice principles that reflect what best care looks like to people with Long COVID. These are presented in both plain language and clinical or professional terminology.

The chapter includes several reflection and learning activities to help you translate the best care principles into your practice. These activities consider your current understanding of best care in Long COVID, a self-assessment of your current approach to partnering with people experiencing Long COVID, the development of an Action Plan to improve your or your services work with these patients and the opportunity to apply your new understanding to two of the personas in this book. This chapter will provide you with an overview of what ‘best practice’ looks like, and there will be many opportunities to dive more deeply into the substance of each principle in other chapters throughout this book.

Reflection (10 mins)

What are your current assumptions about best care practices in the care of people with Long COVID?

- Who do you think it includes?

- Who delivers or receives it?

- Where does it happen?

- When does it happen?

Brainstorm your ideas with colleagues to highlight different approaches to this question, or show your ideas to someone else and discuss.

Providing the best care for people living with Long COVID.

Before considering best care principles, it is worth reflecting on what we mean by ‘best care’. The concept of best care refers to the highest possible standard of care that a patient can receive, including accessibility, personalisation and effectiveness. Best care is described as working in partnership with colleagues and patients to achieve high-quality care that is safe, person-centred, right and coordinated [1]. Best care is closely linked to patient expectations; however, patients are just one of many perspectives on what is considered best care [2]. Best care is often characterised as being founded on specific values, including compassion, excellence, and respect for a patient’s dignity and autonomy [3]. Another related (but distinctive) concept relevant to best care is value-based care, which asserts that best care must provide good financial value to both the patient and the broader community, thereby ensuring limited healthcare resources are being allocated to the greatest possible benefit [4]. The video below explains the concept of value-based healthcare, which is increasingly perceived as being synonymous with the best care and the promotion of equity.

Video by Australian Centre for Value-Based Health Care, via YouTube

Given the novelty of COVID-19 and the complexity of Long COVID, providing the best care for patients will be extremely challenging for some time. The lack of certainty about which interventions are effective and acceptable in supporting an optimal recovery from COVID-19 can be a source of moral distress and frustration for health professionals and other caregivers. Moral distress occurs when it is impossible for health professionals and other caregivers to act in a way they consider ethically correct or provide best care [5]. International studies have highlighted that many healthcare workers are currently experiencing poor mental health, and their mental health may be deteriorating due to the sustained pressure of the COVID-19 pandemic [6] [7]. Healthcare workers face potential barriers to providing best care, including sudden changes in clinical practice as new waves of COVID-19 infection arrive and the overall extreme pressure healthcare systems continue to experience. Health professionals and other carers are also, of course, members of the general community and have, therefore, also experienced the negative impacts of the pandemic, such as concerns about family members becoming infected, managing school-aged children who are learning remotely or experiencing job insecurity.

“The experience at the hospital was good. There were a few misses here and there, but it wasn’t over the top or anything. They were just doing the best they could” (Female, 40-49 years)People with Long COVID understand the restrictions and challenges their healthcare workers are facing. While many people with Long COVID are understandably frustrated about the slow pace of progress in identifying effective treatments and therapies, they also understand that Long COVID is a novel condition. Therefore, healthcare professionals are still learning about and researching the condition and the best ways to provide care for people with Long COVID. A consistent theme from the participants in an ongoing Australian qualitative study [8] has been they wish healthcare workers would be honest about the limits of their knowledge. Perceptions that healthcare workers are overstating their expertise in this area can particularly damage therapeutic relationships. “I don’t know, but I’ll try to find out for you” is a perfectly acceptable answer.

Tools to support best care in practice.

To deliver the best care to people with Long COVID, we need to adopt the best practices. Best practice is a broad concept, and there is no single accepted definition. However, most definitions emphasise that best practice should be based on the latest scientific evidence, supplemented by clinical expertise and supported by resources such as formalised guidelines, protocols and processes [9]. As stated by Hamilton, “Best practice refers to the clinical practices, treatments, and interventions that result in the best possible outcome for the patient and the health care facility providing those services” [10]. Best practice can occur in any area of healthcare, including health promotion, prevention, acute treatment, management of chronic conditions and quality assurance measures (such as patient safety and infection control).

While the role of patients has become more explicit in definitions of evidence-based practice in recent years, recognition of their contribution to quality healthcare is yet to be included in formal definitions of ‘best practice’. Healthcare system perceptions of best practices are still founded on the expertise offered by research and clinicians. Patient involvement is most often found at the direct care level as they participate in their own healthcare treatment [11]. However, changes in the way patients are included in healthcare systems worldwide have the potential to enable our aspirations of providing ‘best care’ to become a reality in everyday practice.

Reflection (60 mins)

- Read pages 7 to 29 of the Safer Care Victorian Partnering in Healthcare Framework.

- Review the Partnering in Healthcare Self-Assessment Tool, and choose one of the domains. Evaluate your current practice with people experiencing Long COVID and identify opportunities to further develop your partnerships. Please note: You do not have to share your assessment with anyone, and only services in the Australian state of Victoria have the option (if they wish) of sharing it with Safer Care Victoria.

This framework is one of many that describe patient engagement. You may choose to complete this activity using another framework that better reflects the needs of your service or your local community. Regardless of the framework you choose, the Self-Assessment Tool above provides guidance on the key prompts and questions you should consider.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted both the potential and fragility of consumer and community engagement in health service and evidence base development, with the initial wave of cases provoking a 58% drop in projects involving patients in the United Kingdom alone [12] [13]. This was reflected in the Rehabilitation Research Framework for Patients with COVID-19 produced by WHO and Cochrane Rehabilitation in May 2020, which was drafted without the input of patients, families, or representatives of consumer organisations [14]. The exclusion of consumers (and the broader community) from COVID-19 research is counterproductive, given how important trust in scientific guidance is to reducing the spread of COVID-19 [15], and the strong influence of politics and culture on how both patients and the broader community make sense of Long COVID and the pandemic overall [16].

Co-Producing Best Practice Principles for Working with People Experiencing Long COVID.

More recently, there has been improvement in patient involvement in COVID-19 research and service development as the world has adjusted to its ‘new normal’. Both the Australian [17] and United Kingdom [18] Clinical practice guidelines for the clinical care of people with COVID-19 include contributions from consumer panels. Patient-led research began early in the pandemic by groups such as Body Politic [19] and is ongoing. Nevertheless, patient-led or co-designed models of care, quality standards or principles for health services remain a rarity despite repeated calls for their development in the literature [20] [21].

Existing Best Practice Guidelines for People with Long COVID

Ladds et al. [22] proposed clinical quality standards for healthcare services about the care of people with Long COVID based on the findings of a study about healthcare workers experiencing this syndrome after infection in the initial 2020 pandemic waves. This qualitative study (n=114) explored the lived experience of these consumers and their preferences around the support and services that would help their recovery. The participants emphasised a need for patient-centred and personalised care, early identification and intervention, support for self-management and access to multidisciplinary treatment and rehabilitation. They also highlighted the importance of involving lived experience experts and their carers in developing future services for people with Long COVID. The table below summarises the clinical quality principles developed from the researcher’s analysis of these interviews.

This research and the resulting principles have made a valuable contribution to our understanding of the lived experiences and needs of Long COVID patients. The authors were the first to suggest the importance of underpinning care principles when developing and implementing new health services to meet the needs of people with Long COVID. Although the study had a relatively large sample size and explored consumer preferences, healthcare workers are a very specific group of people living with Long COVID. They tend to be more highly educated and health literate and have better resources. Their status as ‘insiders’ could also be interpreted as a double-edged sword; they may be better placed to recommend workable quality standards but could also unintentionally perpetuate existing limitations within the system. The quality standards developed in the research were also initially drafted by the research team before being presented to the consumers for comment and feedback, which reflects a consultation ( ‘doing for’) rather than a co-design or co-production (‘doing with’) approach to patient engagement [23]. In terms of co-production, ‘doing with’ is far preferable to ‘doing for’.

The Process of Co-Producing with Lived Experience Experts

In 2021, a team of researchers and people with Long COVID (lived experience experts) worked together to co-produce Long COVID best care practice guidelines. Co-production of these best care principles occurred as part of a research project which received ethics approval from an Australian metropolitan public health service (Western Health, Melbourne) (HREC/2020/WH/70312). The project was undertaken in partnership with the Institute of Health Transformation at Deakin University, Geelong, which provided a seeding grant to support its completion. This study utilised a co-design process that incorporated and built upon existing evidence to support rapid translation into practice. The co-design process was founded on the principles of Experience-Based Co-Design (EBCD) [24] and collected both quantitative (numerical) and qualitative (text) data [25]. While engagement with consumers from the beginning of the co-design process is considered best practice [26], the abbreviated approach adopted ensured the feasibility of the study in the context of Australia’s third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (September – December 2021) and the redeployment of co-design team members to frontline COVID-19 response duties. Each step of the co-design process is described in greater detail below.

As shown in the e-booklet below, the co-production process included contributions from multiple stakeholder groups and multiple data sources. The following description is intended to provide an overview of the process, and more specific detail about each step is available from the authors upon reasonable request.

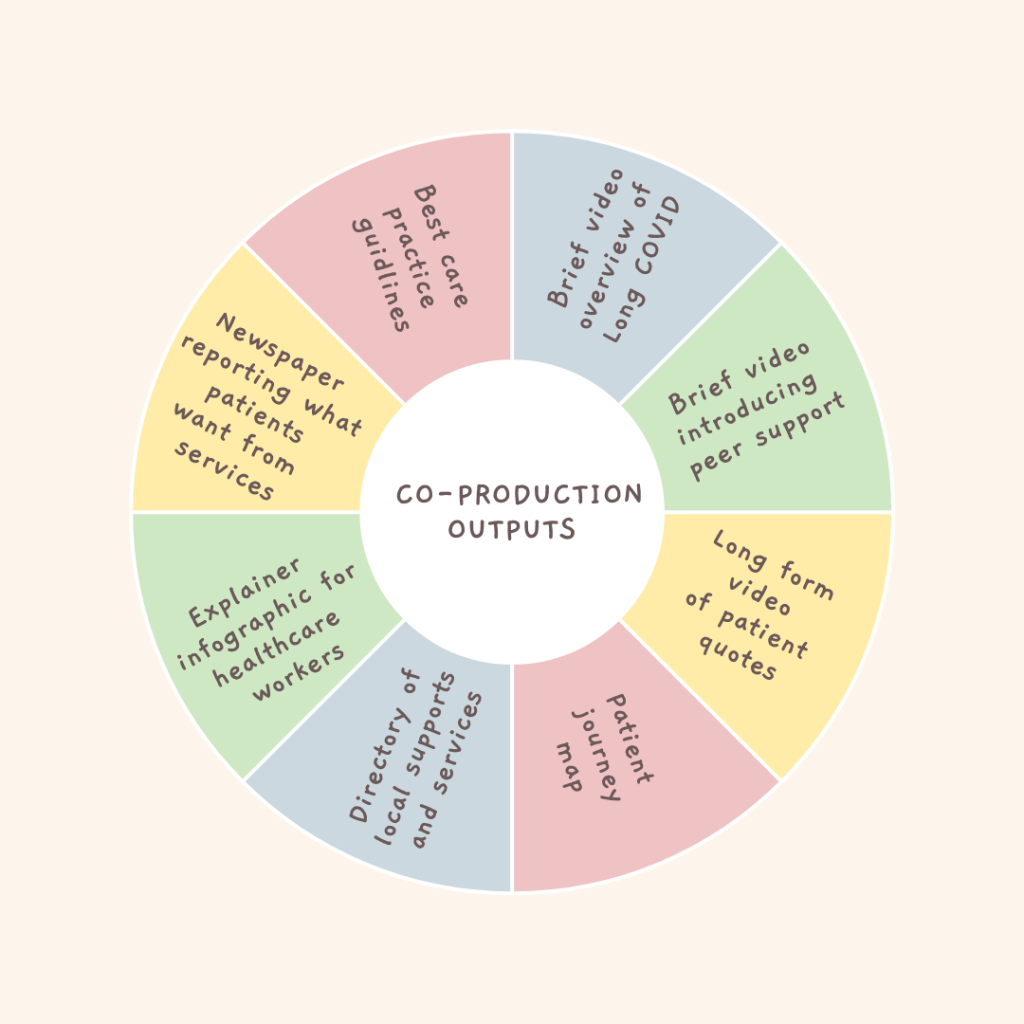

The best practice principles described here were just one of several outputs from this co-design process, all of which were consciously designed to be accessible and embedded in the evidence gathered by the team and available in the broader literature.

Throughout the co-design process, continual data analysis allowed the timely review and discussion of findings to inform the next step. All quantitative data from the outcome measures and the healthcare worker survey were analysed using SPPS (Version 27) [27] and evaluated with descriptive statistics. Reflexive thematic analysis was employed to analyse the patient interviews and qualitative healthcare worker survey data, following the methodology outlined by Braun and Clarke [28]. The Dedoose online platform [29] was used to manage the large amount of quantitative and qualitative data collected during the co-design process, which supported interrogation between the quantitative and qualitative findings. Comparative analysis between all data sources continued iteratively throughout the study to support triangulation, ensuring rigour and providing coherence to the overall findings.

Communicating Co-Produced Best Practice Principles

The co-design team frequently reflected on language and held the shared belief that ‘words matter’. These discussions prompted the research team to reflect on the concept of health literacy, which is usually defined as a patient’s ability to access, understand, and use information to make informed decisions about their health [30].

“At the moment, it’s Facebook groups, and I don’t know what these people are saying … I don’t know if it’s, you know, all wacky” (Female, 30-39 years).Improving patient health literacy requires a transdisciplinary approach to care and promoting health literacies [31] across multiple formats, including print, oral and digital communications [32]. Some approaches to health literacy also involve consumer education about critically appraising health information from online forums, which was also commented upon by one of the research participants. However, most current health literacy approaches reflect a ‘deficit’ approach, where information generally flows from one direction (i.e. from health experts to the patient). This approach emphasises a gap between the valued (and sometimes paternalistic) knowledge of health experts and the less knowledgeable patients. From this perspective, it is the patients’ responsibility to educate themselves and bridge the gap [33]. This approach to communicating our best practice principles seemed at odds with the overall values and philosophy of co-production.

The finalised best practice principles, therefore, reflected a dialogue approach to science communication, which engages with context and encourages a collaborative approach to translate the findings into practice [34]. Dialogue approaches are designed to encourage symmetrical and mutual communication between researchers, healthcare workers and lived experience experts by including non-scientific perspectives and not assuming scientific authority is privileged [35]. The producers of new knowledge (in this case, the co-design team) and the people who will use it in practice (healthcare workers) are interdependent, and successful dialogues depend on both the sender and the receiver.

In this spirit, the principles are expressed in everyday language and then translated into ‘professional’ language to educate healthcare workers on how they can be translated to their practice. The lived experience experts in the co-design team emphasised the need for plain language principles as an authentic expression of the voice of patients. While jargon and technical language are necessary for effective communication in some situations, the description of general behaviour offered by these principles is appropriately conveyed in the everyday language of patients. By privileging plain language, these best practice principles, therefore, flip traditional approaches to health literacy and offer an opportunity for health professionals and other carers to improve their ‘patient literacy’.

The Principles.

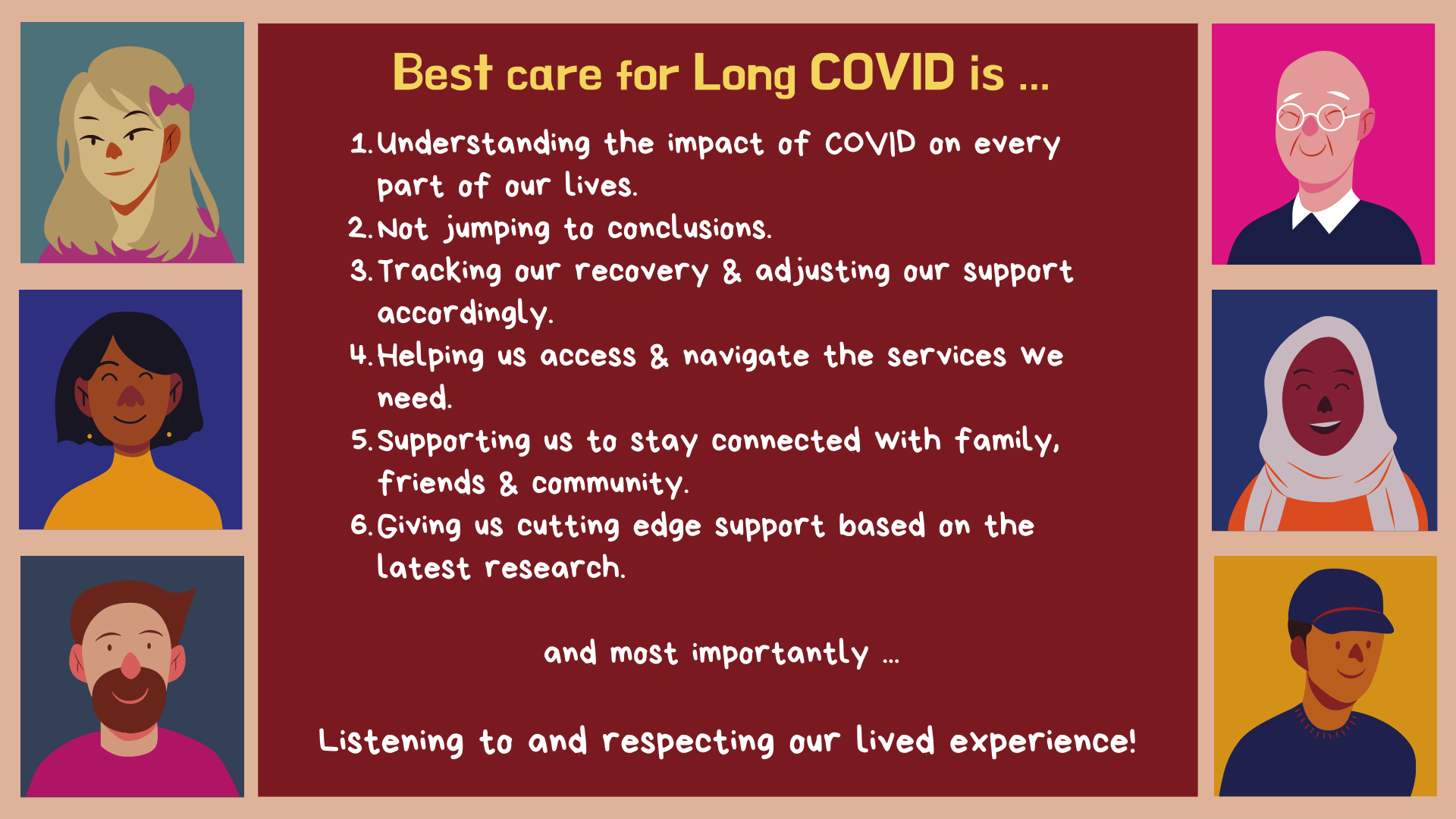

Seven best practice principles were identified and developed by the co-design team, which reflect the preferences of people with Long COVID regarding best care practices. The following flash cards will introduce you to the best care practice principles in plain language (front) and their related professional terms (back).

The following poster summarises the best care principles in plain language and reflects the inclusive approach that lay at the foundation of their development.

Reflection (20 mins)

Many of the ‘big issues’ in modern healthcare have a direct relationship with these best care principles. Consider what they ‘look like’ in your own practice or the practices of your service. Use a copy of the table below to identify what you (or others) might say and do that reflects the influence of these issues (Downloadable Table Template). You may use dot points, and each response should be brief. It’s OK if you don’t have a response for some of these issues …. these may be aspects of the principles you choose to develop in the future.

Please note: Not all health professionals diagnose as part of their role, and this term can be reworked as ‘assessment error’.

| Principle | Healthcare Issues & Terminology | What do you (or others) say? | What do you (or others) do? |

| 1 | Comprehensive biopsychosocial assessment | ||

| 2 | Diagnostic / assessment error | ||

| 2 | Gaslighting | ||

| 3 | Goal setting | ||

| 3 | Outcome measures | ||

| 4 | Integrated Care | ||

| 4 | Care Co-Ordination | ||

| 5 | Social Inclusion | ||

| 6 | Evidence-Based Practice | ||

| 6 | Evidence-Informed Practice | ||

| 7 | Co-Production | ||

| 7 | Person Centred Practice |

How can I take ‘best care’ from aspiration to reality?

Now is the time to translate the best care practice principles into your own practice as a healthcare professional or other caregiver. Every practice context is different, and undertaking a Strength, Weakness, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) analysis will help you to the identify internal and external factors that impact on your ability to provide best care to people with Long COVID. Please watch the following video to get an overview of how SWOT analyses can inform practice improvements.

“SWOT Analysis” by DIY Toolkit – YouTube is licensed under CC BY 3.0.

Learning Activity

Complete the Action Plan template below which provides an opportunity to complete a SWOT analysis for each of the 7 principles of best care practice when working with people with Long COVID.

- The Action Plan can be completed either individually or as a group.

- No time guide has been provided for this activity as it can be completed in a number of different ways. You may choose to complete all principles at once or select one or more to focus on.

- We would encourage you to consider the principles from both your individual perspective and the organizational perspective of your healthcare service. However, you may choose to only focus on one of these domains.

- The template is in an editable Word format, and each box can expand to include as much or as little detail as you wish. You can also download and save the template for future reference or updates.

- Please remember to correctly attribute this template whenever you refer to it in publications or presentations.

Please click here to download: Best Care Principles Goals and Action Plan V1

Providing best care to people with Long COVID.

These best care principles can be modified or adapted to meet the needs of individual patients in many different ways. This process is part of their ‘translation’ to practice, and no two applications of these principles will be exactly the same due to variations in individual circumstances and needs. As you’ve seen in the learning activity above, the principles can be applied from the service provider’s perspective to benchmark current practices and identify opportunities for further development and improvements. They can also provide a foundation for vision or mission statements and for developing key performance indicators that articulate expected behaviours when working with people experiencing Long COVID.

However, best care principles can also be helpful for working with individual patients and families. The principles presented here were derived specifically from the lived experience of people with Long COVID, and the alignment of treatment plans could document and guide collaborative discussions with patients. For example, treatment plans could be supplemented by plain language summaries of the evidence available for a specific intervention or include a specific section about promoting social connections. Patient education resources could be developed for each of these principles as part of an overall model of care, which illustrates how these broad concepts inform specific goals or actions. Ensuring that patients know you or your service’s commitment to these principles can also promote accountability, particularly if you encourage people with Long COVID to give you feedback about your performance against each of them.

Learning Activity (30 mins)

Read the ‘COVID-19’ section of the personas of Josh and Jen (from Acute Infection to Current Situation). Using the worksheet below, note down aspects of their lived experience that reflect each of the principles of best care practice.

- Can you identify areas of good practice? Were there also some examples of areas for improvement?

- What do you think the supports and services they access could do different in future?

- What factors do you think influenced the differences in their experiences? Could these factors be acted upon to promote better outcomes?

Please click here to download: Applying Best Care Principles to Josh and Jen

Conclusion

Two perspectives on the question “What is Long COVID?” have been presented in this chapter – the current knowledge of healthcare researchers and practitioners and the lived experience expertise of patients. Clearly, this syndrome is far more than a collection of commonly co-occurring symptoms. The COVID-19 pandemic has been as much a social phenomenon as a global healthcare emergency, and the knowledge required to engage with its pervasive impact (including Long COVID) originates from multiple disciplines and ways and understanding [36]. Long COVID, in particular, highlights the complex and constant interplay between the multitude of biopsychosocial factors that influence health and well-being. No wonder researchers, healthcare practitioners and patients alike feel overwhelmed.

As highlighted in this chapter, Long COVID means different things to different people, and a ‘one size fits all’ approach cannot be applied. Our knowledge of Long COVID is evolving at lightning speed, with multiple new challenges and opportunities always emerging. Ultimately, Long COVID reminds us of the inherent unpredictability of life and spotlights the limitations of our knowledge. It forces us to confront the fact that sometimes we have to live with uncertainty and discomfort – for the foreseeable future, we will be ‘flying the plane while building it’. [37]. This chapter has, therefore, just scratched the surface of what there is to know and understand about Long COVID … but we all have to start somewhere.

For More Information

The following links will provide you with additional general information about Long COVID from creditable sources. These listings are not exhaustive, and you are encouraged to seek out locally relevant information for your community.

- An analysis of supports and opposition to patient-centric culture during the pandemic: Patient-centric culture and implications for patient engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- A commentary on the impact of the pandemic on co-production: Co-Production during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: Will it last?

- A video presenting both patient and physician perspectives on Long COVID: “The Effects of Long COVID: A physicians and patient’s perspective” by Patient Safety Movement is licensed under CC BY 3.0.

- Western Health. (2019). Best Care Framework June 2019. Available from www.westernhealth.org.au/Careers/Documents/Best%20Care%20Framework%20document.pdf ↵

- Krause, F., Boldt, J. (2018). Understanding Care: Introductory Remarks. In: Krause, F., Boldt, J. (eds) Care in Healthcare. Palgrave Macmillan ↵

- Halligan A. (2008). The importance of values in healthcare. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 101(10), 480–481. ↵

- Rech Ramos, P. (2021). Value-Based Healthcare. IntechOpen. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.93378 ↵

- Beltrao, J.R., Figueiredo, B., Sachetim, G., Aihara, L., Aihara, L., & Corradi-Perini, C. (2022). Healthcare professional’s moral distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: an integrative review. Research, Society and Development, 11(14), e281111436435. ↵

- Hitch, D., Booth S., Wynter K., Said, C., Haines, K., Rasmussen, B., & Holton S. (2023) Worsening general health and psychosocial wellbeing of Australian hospital allied health practitioners during the COVID-19 pandemic. Australian Health Review, 47, 124-130. ↵

- Gholami, M., Fawad, I., Shadan, S., Rowaiee, R., Ghanem, H., Hassan Khamis, A., & Ho, S. B. (2021). COVID-19 and healthcare workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of infectious diseases : IJID : official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases, 104, 335–346. ↵

- Hitch, D., Deféin, E., Lloyd, M., Rasmussen, B., Haines, K., & Garnys, E. (2023). Beyond the case numbers: Social determinants and contextual factors in patient narratives of recovery from COVID-19. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 47(1), 100002. ↵

- Hamilton, K. (2011). What Constitutes Best Practice in Healthcare Design? Health Environments Research & Design Journal (HERD) (Vendome Group LLC), 4(2), 121–126. ↵

- Hamilton, K. (2011). What Constitutes Best Practice in Healthcare Design? Health Environments Research & Design Journal (HERD), 4(2), 121–126. ↵

- Horvat, L. (2019). Partnering in healthcare for better care and outcomes. Safer Care Victoria, State Government of Victoria: Melbourne. ↵

- Denegri, S., & Starling, B. (2021). COVID-19 and patient engagement in health research: What have we learned? Canadian Medical Association Journal, 193(27), E1048-E1049. ↵

- Health Research Authority. (2021). Public involvement in a pandemic: lessons from the UK COVID-19 public involvement matching service. London: National Health Service ↵

- Negrini, S., Mills, J., Arienti, C., Kiekens, C., & Cieza, A. (2020). “Rehabilitation Research Framework for Patients With COVID-19” Defined by Cochrane Rehabilitation and the World Health Organization Rehabilitation Programme. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 102, 1424-1430. ↵

- Pagliaro, S., Sacchi, S., GPacilli, M., Brambilla, M., Lionetti, F., Battache, K., Bianchi, M., Biella, M., Bonnot, V., Boza, M., Butera, F., Ceylan-Batur, S., Chong, K., Chopova, T., Crimston, C., Álvarez, B., Cuadrado, I., Ellemers, N., Formanowicz, M., Graupmann, V., Gkinopoulos, T., Jeong, E., Jasinskaja-Lahti, I., Jetten, J., Bin, K., Mao, Y., McCoy, C., Mehnaz, F., Minescu, A., Sirlopú, D., Simić, A., Travaglino, G., Uskul, A., Zanetti, C., Zinn, A., & Zubieta, E. (2021). Trust predicts COVID-19 prescribed and discretionary behavioral intentions in 23 countries. Plos ONE, 16(3), e0248334. ↵

- Campbell, S. (2021). Interpretation of illness and COVID-19. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 9(4), 1-4. ↵

- National Covid-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce. (2022). Caring for people with COVID-19: Living Guidelines. Available from https://covid19evidence.net.au/#living-guidelines. ↵

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), & Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP). (2022). COVID-19 rapid guideline: Managing the long-term effects of COVID-19. Version 1.14. In. London: NICE, SIGN, RCGP. ↵

- McCorkell, L., Assaf, G., Davis, H., Wei, H., & Akrami, A. (2020). Patient-Led Research for COVID-19: Embedding Patients in the Long COVID Narrative. Available from https://osf.io/n9e75/ ↵

- Hensher, M., Angeles, M., de Graaff, B., Campbell, J., Athan, E., & Haddock, R. (2021). Managing the long-term health consequences of COVID-19 in Australia. In. Canberra Deeble Insitute for Health Policy Research. ↵

- McClymont, G. (2021). The role of patients and patient activism in the development of Long COVID policy. Cambridge Journal of Science & Policy, 2(1), 1-12. ↵

- Ladds, E., Rushforth, A., Wieringa, S., Taylor, S., Rayner, C., Husain, L., & Greenhalgh, T. (2021). Developing services for long COVID: lessons from a study of wounded healers. Clinical Medicine, 21(1), 59-65. ↵

- Australian Mental Health Commission (2017). Consumer and carer engagement: A practical guide. vailable from www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/getmedia/afef7eba-866f-4775-a386-57645bfb3453/NMHC-Consumer-and-Carer-engagement-a-practical-guide. ↵

- Dimopoulos-Bick, T., O’Connor, C., Montgomery, J., Szanto, T., & Fisher, M. (2019). “Anyone can co-design?”: A case study synthesis of six experience-based co-design (EBCD) projects for healthcare systems improvement in New South Wales, Australia Patient Experience Journal, 6(2), Article 15. ↵

- Cresswell, J., & Plano Clark, V. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE. ↵

- Fylan, B., Tomlinson, J., Raynor, D. K., & Silcock, J. (2021). Using experience-based co-design with patients, carers and healthcare professionals to develop theory-based interventions for safer medicines use. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 17(12), 2127-2135. ↵

- IBM Corp. (2020). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 27.0) [Computer software]. IBM Corp. ↵

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. London: Sage ↵

- Dedoose Version 9.0.17, cloud application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed-method research data (2021). Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC www.dedoose.com. ↵

- Peerson, A., & Saunders, M. (2009). Health literacy revisited: what do we mean and why does it matter? Health Promotion International, 24(3), 285–296, ↵

- Mackert, M., Champlin, S., Su, Z., & Guadagno, M. (2015) The Many Health Literacies: Advancing Research or Fragmentation? Health Communication, 30(12), 1161-1165, ↵

- Nutbeam, D. (2009). Defining and measuring health literacy: what can we learn from literacy studies? International Journal of Public Health, 54, 303–305. ↵

- Stocklmayer, S. (2012). Engagement with science: Models of science communication. In: Gilbert JK, Stocklmayer S, editors. Communication and engagement with science and technology: Issues and dilemmas - A reader in science communication. London: Taylor & Francis Group, 19-38. ↵

- Trench, B. (2008). Towards an analytical framework of science communication models. In: Cheng D, Claessens M, Gascoigne T, Metcalfe J, Schiele B, Shi S, editors. Communicating science in social contexts. Dordrecht: Springer, 119-135. ↵

- Gross, A.G. (1994). The roles of rhetoric in the public understanding of science. Public Understanding of Science, 3(1), 3-23. ↵

- Leach, M. (2020). Pandemics are social phenomena, demanding breadth of expertise. WONKHE. Available at https://wonkhe.com/blogs/pandemics-are-social-phenomena-demanding-breadth-of-expertise/ ↵

- Hitch, D. (2023). Long COVID: Why isn't anyone listening? Available at https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2023/8/long-covid-why-isnt-anyone-listening/ ↵