1 What is Long COVID?

By Danielle Hitch

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter and completing the learning activities, you will be able to:

- Reflect upon your current knowledge about Long COVID, and identify areas you wish to develop.

- Understand how Long COVID is currently described and defined.

- Identify the most common symptoms of Long COVID.

- Analyse a sub-phenotype presenting in an individual with Long COVID.

- Examine the lived experience of Long COVID from the patient’s perspective.

- Create a patient journey map for an individual with Long COVID.

- Identify further resources to support your ongoing development in this area.

Introduction

Long COVID affects millions of people worldwide, and its impact on individuals, healthcare systems, economies and broader society is still not fully understood. This chapter aims to provide a comprehensive overview of Long COVID, including its characteristics, symptoms, and risk and protective factors. We will also provide an overview of the current evidence in this field and explore the lived experience of Long COVID from the patient’s perspective. There is a huge amount to learn about Long COVID, and this chapter will provide you with a launching pad for your further learning in this area.

What do you already know about Long COVID?

There is growing recognition of Long COVID, as the longer-term effects of COVID-19 infection become more apparent. It’s likely you already have at least some understanding of this condition, even if you have not studied it or treated people that experience its symptoms. Before you begin reading this chapter, we would like you to reflect on what you know already – this is the foundation you will build upon.

Reflection (10 mins)

Use the Padlet below to post what you know about Long COVID. What are the symptoms? What issues can it cause people? What causes Long COVID, and what treatments are available? You can also comment on other posts, but remember – This is a public board, and please do not include any identifying information.

Have you identified any gaps in your knowledge? If so, note them down and see if this chapter helps you develop your knowledge.

As an introduction to this chapter, take a couple of minutes to watch the following video. It was co-produced with people experiencing Long COVID and included the information they want people in the broader community to know about the syndrome.

While most people fully recover from acute COVID-19 infection, some continue to experience symptoms that persist for months or years. There are many names for these symptoms – Post-Acute COVID19 Syndrome (PACS), Post-Acute COVID19 Condition (PACC), Chronic COVID Syndrome (CCS), Long-haul COVID, Persistent Post-COVID19 Syndrome (PPCS), and Long-term effects of COVID (LTEC) [1] [2]. As stated in the introduction chapter, the term Long COVID is used in this textbook in recognition of its identification by consumers and common use in the community. [3] [4] [5] [6] [7]

Definitions and descriptions of Long COVID.

Several definitions and descriptions of Long COVID are available internationally, most of which are broadly similar. Five of these descriptions are presented in the boxes below for your review.

Learning Activity (20 mins)

Using a copy of the table below (Downloadable Table Template ), identify the similarities and differences between the definitions and descriptions in the information wall.

| WHO | NICE | CDC | Great Ormond Street | Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al. | |

| Evidence of COVID-19 | |||||

| The time point for identification | |||||

| Trajectory of symptoms | |||||

| Impact on daily life |

Do the differences between the definitions and descriptions matter to your clinical work? Discuss or reflect upon why or why not.

The impact of Long COVID on the human body.

This section will provide you with general information about the etiology (causes), diagnosis (symptoms), course (recovery) and prognosis (outlook) of Long COVID. Further detail about the syndrome’s impact on specific body functions and body structures will be available in future chapters of this book.

What causes Long COVID?

The short answer is Long COVID is caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Like most aspects of COVID recovery, it’s not as simple as that… Not everyone with an acute COVID-19 infection goes on to have Long COVID. While prevalence estimates vary, many fall within 10%-15% of COVID-19 infections[8]. Currently, we can’t be certain why this amount of people with acute COVID-19 infection experience persistent symptoms long after most others have recovered. However, there are five general hypotheses about potential contributors to Long COVID. None of these factors are considered to be the ‘sole’ cause of Long COVID. Rather, it is likely that they interact in fluid and complex ways.

Possible Causes of Long COVID

Viral Persistence:

- Studies suggest that viral persistence may be caused by the immune system failing to completely clear the virus or by mild persistent infection. Some organs seem particularly susceptible to becoming viral reservoirs, including the lungs [9], the intestines [10] and the olfactory mucosa [11]. More research is needed to fully understand how viral persistence occurs and its relationship to Long COVID. Better knowledge in this area could lead to the effective use of antiviral therapies and immunomodulatory treatments, or the repurposing of existing drugs.

Autoimmune responses:

- These responses occur when a person’s immune system overreacts to the virus or mistakenly attacks their own body. This leads to persistent inflammation and damage to healthy tissues, which can result in a wide range of chronic diseases, several share some similar symptoms with Long COVID (such as rheumatoid arthritis, chronic fatigue syndrome and lupus). While patients with pre-existing autoimmune disorders are considered at higher risk of COVID-19 infection in the first place [12], there is also evidence to suggest there is an increased risk of developing a range of autoimmune diseases following COVID-19 infection[13].

Cardiovascular complications:

- COVID-19 can cause both primary and secondary damage to blood vessels, resulting in reduced blood flow to vital organs [14]. The development of ‘micro-clots’ post-infection has received a lot of attention (some of which is contentious), given their potential to cause hypoxia, oxidative stress and inflammation [15]. The inflammatory response appears to be the main cause of acute cardiovascular complications in COVID-19 [16], which can include myocardial infarction, myocarditis, arrhythmia, heart failure, shock, and venous thromboembolisms / pulmonary embolisms [17].

Neurological Damage:

- Recent studies indicate the COVID-19 virus can cross the blood-brain barrier, potentially causing demyelination or axonal damage [18]. Regardless of the need for hospitalisation in the acute phase of COVID-19, patients are at higher risk of a wide range of neurological problems for at least 12 months following infection. These problems include stroke, cognition and memory disorders, peripheral nervous system disorders, migraine, epilepsy, extrapyramidal and movement disorders, mental health disorders, musculoskeletal disorders, sensory disorders, Guillain–Barré syndrome, and encephalitis or encephalopathy [19]. Structural damage can also occur to neurological organs and tissues, with persistent white matter changes found in COVID-19 patients one year after their infection [20].

Mental Health:

- The anxiety caused by COVID-19 infection may be compounded by the general distress experienced by the community from the broader impacts of the pandemic. Both sources of stress may have long-lasting effects on mental health, which can contribute to Long COVID symptoms. Mental health symptoms are commonly reported by people with Long COVID, including anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances [21]. These symptoms can have a significant impact on the functioning, wellbeing and quality of life of people with Long COVID, who may require multidisciplinary support from healthcare and other sectors to support their recovery [22].

Learning Activity (10 mins)

Along with the potential causes listed above, a better understanding of risk and protective factors for Long COVID is beginning to emerge in the international literature. The strength and quality of evidence supporting these factors and our knowledge of them will likely change and develop in the coming years. Answer the following questions to review current knowledge about risk and protective factors for Long COVID.

[23] [24] [25] [26] [27] [28] [29] [30] [31] [32] [33] [34] [35]

What are the symptoms of Long COVID?

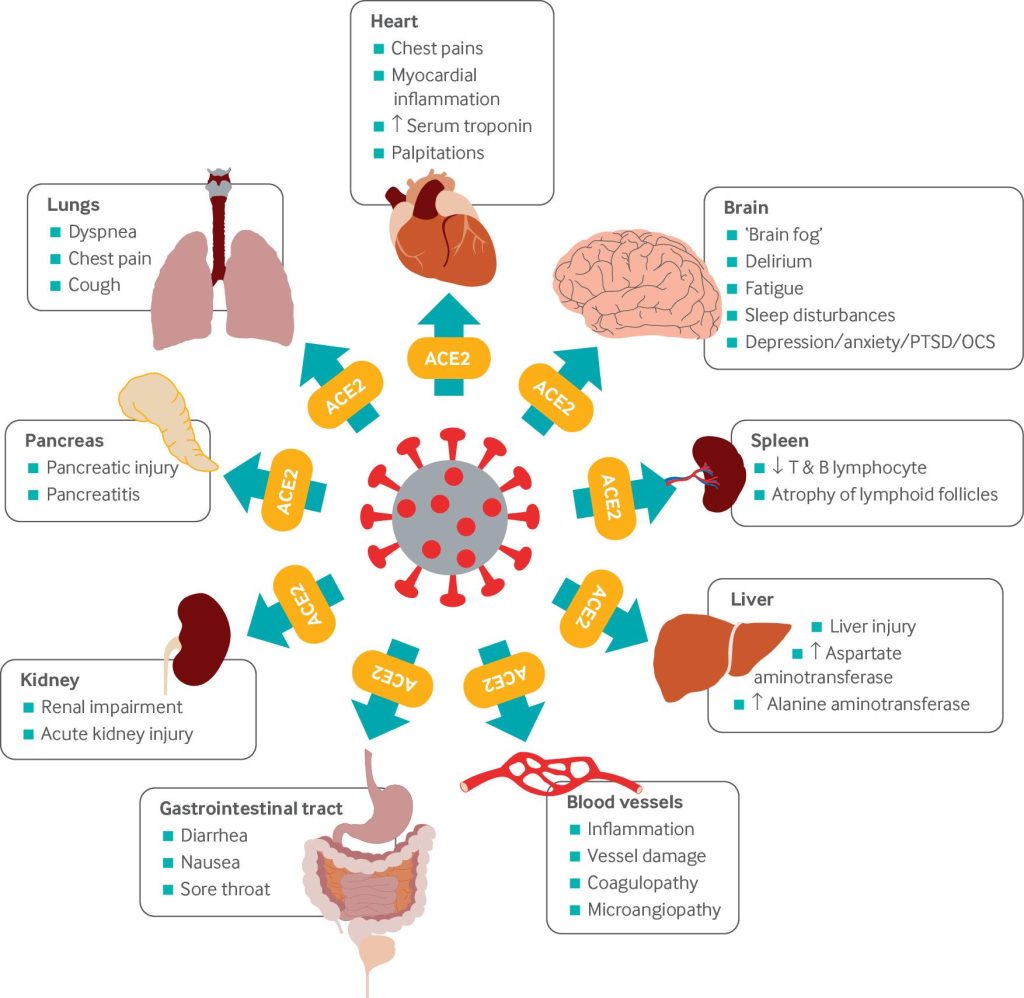

One of the great challenges Long COVID poses is the diversity of its associated symptoms. The syndrome can impact any and all body functions and body structures, with over 200 distinctive symptoms identified by people with Long COVID across 56 countries [36]. Some people may experience only one or two symptoms, while others may experience a constellation of multiple symptoms. As indicated in the figure below, the pervasive effect of the SARS-Cov-2 virus is mediated by its ability to use ACE2 receptors as a means of entering multiple organs.

Learning Activity (15 mins)

Some of the more common symptoms of Long COVID are listed below and were identified from a systematic review and meta-analysis of multiple studies [37]. Word-finding puzzles are a great way to remember new concepts and are much more fun than memorising a list!

What does that mean? [38]

- Ageusia – Loss of taste

- Anosmia – Loss of smell

- Apnoea – Breathing disruptions

- Dyspnoea – Breathlessness

- Dysphonia – Voice changes

- Palpitations – Forceful or irregular heartbeat

- Polypnea – Rapid breathing

- Sputum – Secretions that you cough up

- Tachycardia – Abnormally high heart rate

- Tinnitus – Noise or ringing in your ears or head not explained by external sounds.

The diversity of possible symptoms for Long COVID has led some researchers to try and identify specific phenotypes of symptoms that tend to occur together. Up to 33 characteristics have been identified within the overall Long COVID phenotype [39] [40]. Another general Long COVID phenotype was also shown to differentiate between people effectively hospitalised with Long COVID symptoms from those managed in the community or with no history of COVID-19 infection [41].

Several sub-phenotypes have also been proposed, describing between 3 and 33 distinctive symptom clusters. Some of these sub-phenotypes are also characterised by the number of symptoms they include, with those involving more symptoms generally considered more severe [42] [43] [44]. There is considerable diversity in identified sub-phenotypes, with some overlap between the various clusters of symptoms between the studies. This reflects the complexity of Long COVID and the emerging nature of the research in this field. However, identifying Long COVID phenotypes remains an important goal to ensure consistency across studies, facilitate comparisons between different populations, identify high-risk patients and develop targeted treatment and management strategies for COVID-19.

Learning Activity (15 mins)

Read a persona of your choice from this textbook (see Persona section). List the symptoms the person identifies and their associated body structure or system. You may also draw an outline of the human body and map the symptoms visually. Reflect on the following questions:

How many symptoms do they experience, and what body structures or systems are affected?

Have some of the symptoms changed or resolved over time?

How do the symptoms they have experienced following COVID-19 infection relate to any pre-existing health problems?

Choose an activity of daily living identified as meaningful or important to the person, and imagine them performing this task. Which symptom/s are likely to impact their participation? How might these symptoms pose a barrier to them completing this activity?

What does it feel like to recover from COVID-19?

The narratives of COVID-19 recovery in this section come from an ongoing Australian study, which seeks to understand how patients describe their lived experience of COVID recovery. Five key themes have been identified in their stories: 1) Getting back to my normal, 2) Trajectories of recovery, 3) The importance of work, 4) Fears and uncertainties and 5) Stigma and discrimination.

Getting back to my normal

For most people, the destination for COVID-19 recovery was getting ‘back to normal’. This was conceptualised as their ‘normal’ rather than an externally defined standard, and therefore recovery looked different for each participant. Despite this individual variation, people recovering from COVID-19 could evaluate and describe their personal recovery to a high degree of specificity. Some people described their ongoing recovery from COVID-19 in reference to their symptoms, particularly those who experienced complete recovery; This emphasis on symptoms was also reflected in narratives of post-acute investigations, where test results or professional opinions often conflicted with the lived experience of recovery. The inability of healthcare representatives to explain why they didn’t feel better when test results indicated full recovery was particularly frustrating and disconcerting for many people.

However, in most narratives, being ‘back to normal’ involved more than resolving symptoms. Most described how their participation in daily life changed as their recovery progressed and described how COVID-19 had an impact on all areas of their daily life, including personal and domestic activities, hobbies, exercise, and social or community activities. People who were recovering (rather than recovered) from COVID-19 described dissatisfaction with their current ability to take part in life roles and daily activities. Some had initiated a process of adaptation in response to their residual symptoms and functional issues to maintain some connection with these activities, albeit using a modified format or process. Therefore, recovery entailed adjusting to a new sense of ‘my normal’ rather than returning to their baseline.

Uncertainty about what sort of ‘normal’ could be expected post-COVID-19 was also a prevalent theme. ‘Normal’ for people with pre-existing conditions already included persistent symptoms and functional impairments, which made it difficult to determine what experiences were directly attributable to COVID-19. Many also wondered if their current health resulted from COVID-19 infection, normal ageing, or the pervasive societal changes everyone has experienced due to the pandemic. ‘My normal’ is perceived within the context of the ‘new normal’ to which everyone has needed to adjust. During the earlier phases of the pandemic, public health measures such as restrictions and lockdowns were a compounding factor that delayed or impeded recovery for some people with COVID-19; The impact of these measures on usual levels of physical activity was also described in several narratives as particularly detrimental to cardiovascular, respiratory, and musculoskeletal recovery.

Only people recovering from COVID-19 can define what ‘their normal’ looks like, and they are best placed to evaluate their progress towards it.

- “I think I’m pretty well getting back to normal now” (Female, Aged 50+)

- “I’m like 90% back to not having the impacts of it” (Male, Aged 30-49)

Symptoms provide a benchmark for progress towards recovery.

- “[The health department] cleared me on the 18th, and that was purely according to my symptoms.” (Female, Aged 30-49).

- “I got an email from the [health department] just telling me I’m well enough to go back to work. It was 10, 11 [days] or something. So, I rang them, and I said, no, no, no, you obviously haven’t communicated between you all. I’m still really not well enough” (Female, Aged 50+).

- “The resounding response from everybody is we don’t know … It’s okay; your lungs are okay. Uh, yes, we can see that [you’re] not right. (Female, Aged 30-49)

COVID-19 recovery is also about what the symptoms mean to your ability to participate in daily life.

- “I was feeling quite reckless, getting from our bedroom, which was on the first floor, down to the kitchen and back again. So I struggled with that for a couple of weeks, but now, all sort of well and recovered” (Female, Aged 50+)

- “I’m back, walking, playing golf, doing all the things that I do” (Male, Aged 50+).

- “I can’t carry out my daily activities as well, pre-COVID diagnosis. So, they’re the main things that I’m dealing with at the moment” (Female, Aged 30-49).

- “So, it’s stuff that I’m adapting to, to make sure that I am still managing it well, but it is just something that I’ve had to adjust to.” (Female, Aged 18-29)

What even is normal anymore?

- “You will be talking and then, but again, I’m 62 … (is) this a sign of something else? What was that word? Or what was that?” (Female, Aged 50+).

- “I think the biggest trauma’s been to be honest in my opinion, the lockdowns and the emotional stress of that side of it” (Male, Aged 50+).

- “I don’t know whether I’m just going to put it down to the fact that I couldn’t get over the lack of fitness in my legs after four weeks of doing not much around home, like you couldn’t even go for a walk around the block” (Male, Aged 50+).

Trajectories of Recovery from COVID-19

The participants in the study described three distinct trajectories of recovery: 1) complete recovery, 2) gradual improvement and 3) cyclic/relapsing. Around a third of the narratives described complete recovery, with symptoms resolving during their acute illness. While the focus of this textbook is on Long COVID, it remains important to understand all aspects of recovery from the COVID-19 infection as a potential route to prevention and early intervention. The complete recovery trajectory was predominantly described by younger participants, some of whom recovered before their diagnosis.

However, most people recounted new or persisting symptoms that improved gradually and had progressively less impact on daily life. The speed of improvement varied between participants and between specific symptoms. This slow but steady trajectory also impacted pre-existing conditions for some participants, which were exacerbated by COVID-19 and took many months to return to baseline. It is important to note that the World Health Organisation case description for Long COVID [45] explicitly excludes symptoms that can be attributed to another diagnosis, meaning these patients would not necessarily be identified as having the syndrome.

The third trajectory described cycles of alternating relapse and improvement within an overall course of gradual improvement. Some people experienced a period of feeling better or ‘normal’ before symptoms returned or new problems emerged. Relapses also occurred on a background of gradual improvement, with periods of improvement or plateaus generally becoming longer over time. However, experiences of this trajectory differed from sustained gradual improvement, as their journey felt ‘bumpier’.

Younger people most often reported complete recovery during the acute phase of their COVID-19 infection.

- “I got a phone call on the Wednesday saying that I tested positive, and I was actually completely fine at the time … it was like a bit of a cold for one or two days and then just left” (Female, Aged 18-29).

Recovery from COVID-19 is most often a process of slow but steady improvement.

- “It was a real slow process of feeling better. I went out for some exercise probably [a] week after that, and I could walk maybe 200 metres, and then that was it” (Female, Aged 30-49)

- “So the palpitations are less prominent now, but I still get palpitations most days. And that’s the main feature of my day” (Female, Aged 30-49).

- “After COVID for the first two or three months, my sugar was everywhere. But my sugar has improved a lot, we had got that back on track” (Male, Aged 50+).

Relapses, plateaus and improvements can all occur within a gradually improving recovery.

- “Five weeks, six weeks … I felt like nothing ever happened, did resume as normal activity as I could during lockdown, but then afterwards it kinda came back, and that’s when I thought, Oh God, have I got it again, because (it felt like) what I’ve had in May” (Male, Aged 30-49).

- “So it’s sort of like a two spike sort of attack. It gets really hard, then you get better and then it comes back and hits you a second time” (Male, Aged 50+).

Learning Activity (30 mins)

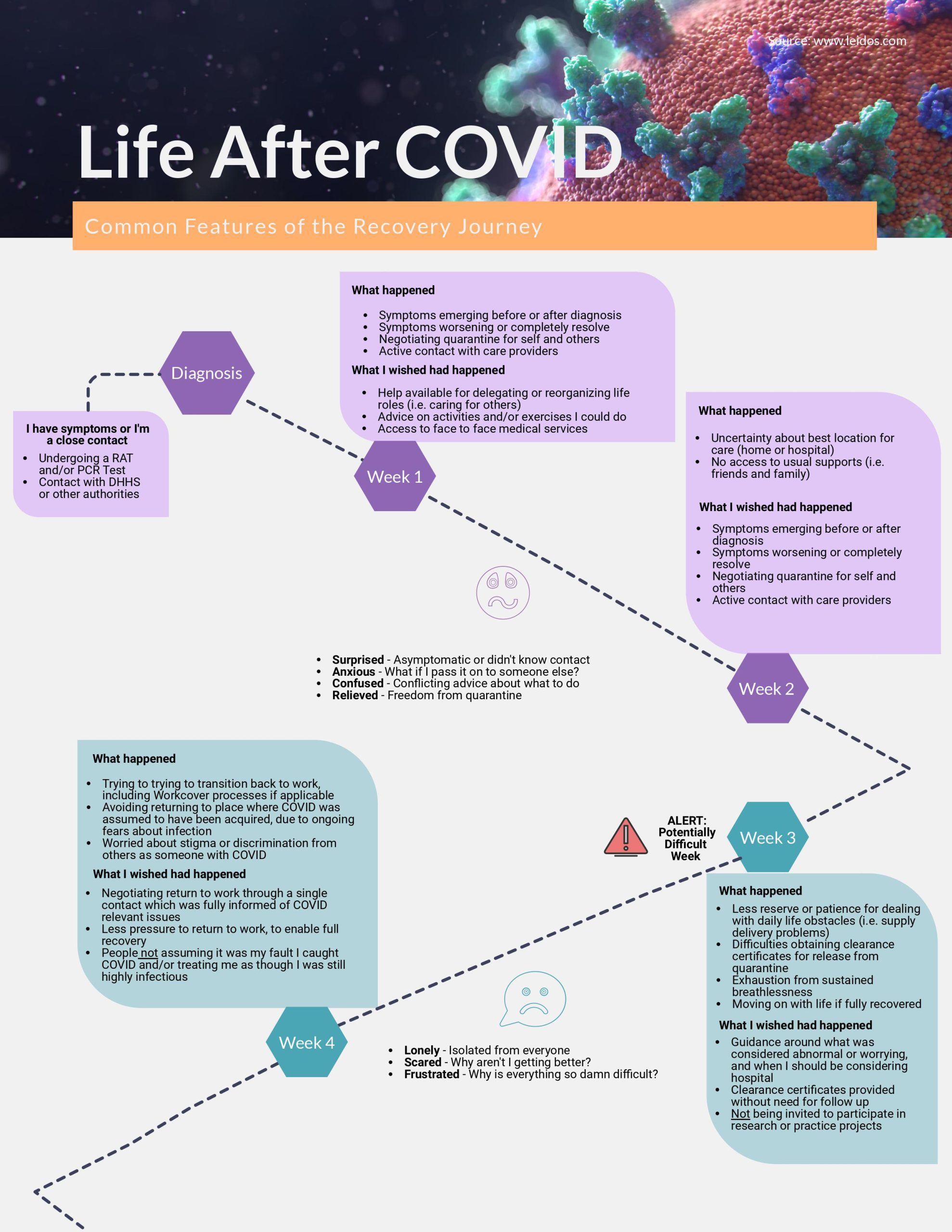

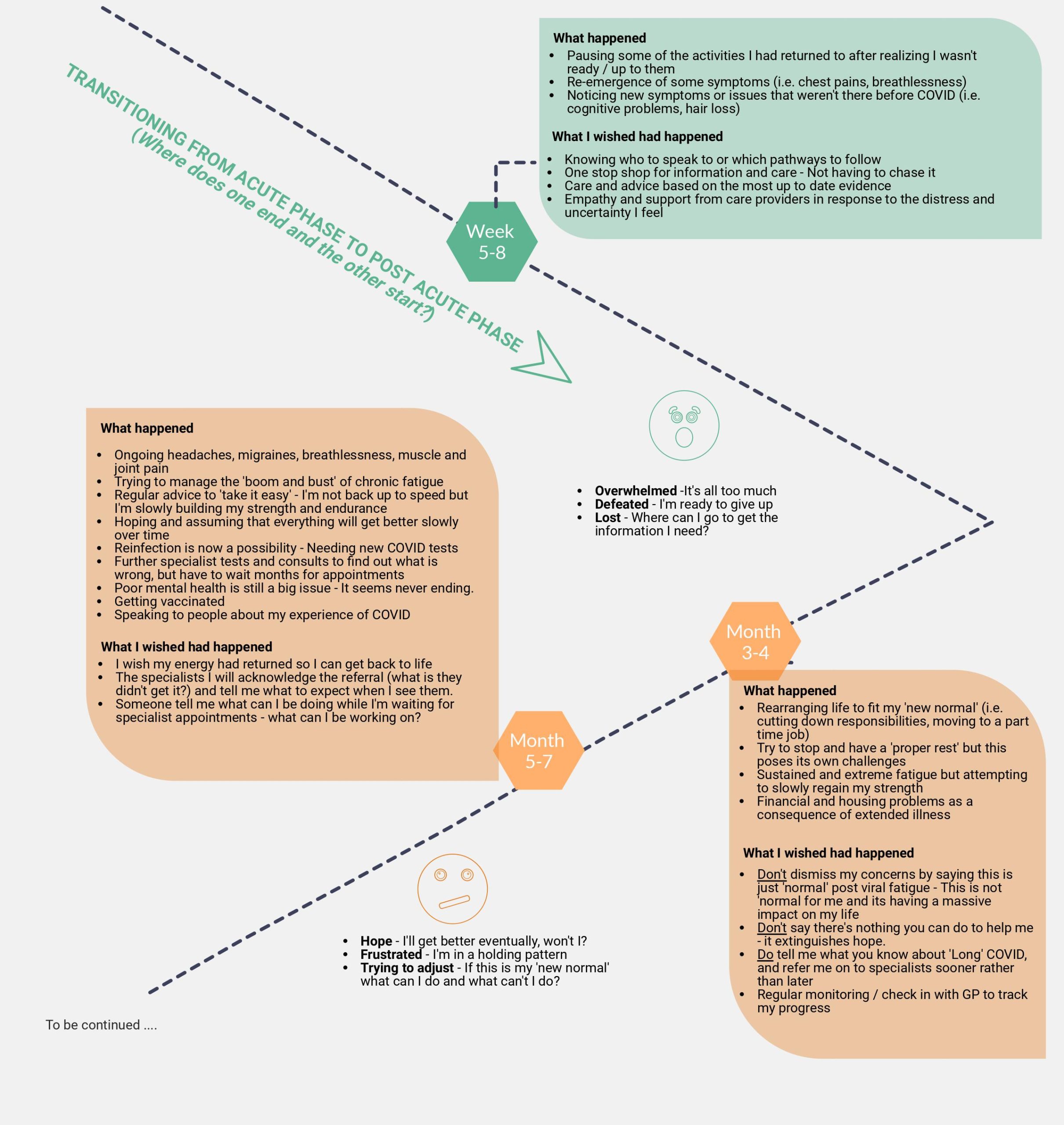

Return to the persona that you chose for the previous learning activity. In this activity, you will be drawing a patient journey map that describes their experience of Long COVID to date. A patient journey map is a diagram of a patient’s experience with a healthcare provider or healthcare system. It shows the patient’s interactions, experiences, and emotions throughout their healthcare journey, from the initial point of contact through treatment and follow-up care. The map outlines key ‘touch points’ in the patient’s journey – these are experiences or contacts with the provider or system which provide an opportunity to improve the patient’s experience. Mapping these ‘touch points’ enables healthcare practitioners to identify areas for improvement in providing patient-centred care.

The following brief video provides an example of patient journey mapping through planning, receiving and recovering from surgery. It shows how every aspect of the person’s care is identified for point in their assessment and treatment.

However, not all patient journey maps are focused exclusively on healthcare services or systems. In late 2021, the following patient journey map was co-produced with six people experiencing Long COVID. The map’s purpose was to illustrate how their lived experience changed over time, although there are references to some of the contacts they had with healthcare providers. Review this map, and in particular, consider how visual features are used to convey the contents and changes over time.

Draw a patient journey map for your chosen persona. You may choose to focus on their healthcare interactions, their lived experience or both. You may choose any format, visuals or aspects of the persona you wish. While this activity can be completed individually, you may find it more helpful to work within a pair or team to ensure multiple perspectives are incorporated into your map.

The importance of work

Many people think of paid employment when considering work; however, there are other productive activities that may be impacted by COVID-19 recovery (including education, voluntary duties and childcare). While the people in this study mostly spoke about paid employment, it is likely their experiences are also relevant to other forms of work. Returning to work was a key sign that things were returning to ‘my normal’ for many people recovering from COVID-19. This was particularly true for healthcare workers, who described the additional stress caused by returning to where they had acquired the virus. Return to work processes were also often experienced as onerous and prevented people from moving beyond their experiences of COVID. Assessment and documentation requirements were an even greater burden for people experiencing brain fog and other functional issues.

Similar to their recovery trajectories, people recounted various return-to-work pathways. Some returned to their previous roles, although the initial weeks were often marked by significant fatigue. Others required a graded return to work with progressively longer hours, while some moved to new positions better suited to their ‘new normal’. Often these new positions involved fewer hours or less demanding duties to take their ongoing symptoms into account, which had a negative impact on their income and potential career progression. The provision of specialist vocational rehabilitation support for these consumers would prevent a considerable loss of productivity to the broader community but is not always available under local jurisdictions and healthcare systems. Implementation of reasonable accommodations in the workplace may also need legislative support, such as recognition of Long COVID as a disability within disability discrimination legislation.

Healthcare workers recovering from COVID-19 face distinctive challenges regarding their work.

- “it’s very triggering to come back into that environment and continually face that over and over again” (Female, Aged 30-49).

- “You are dealing with a few different agencies, you are sort of dealing with your own line management, you are dealing with the [health department] and then in my case I was dealing with [organisation name] as well… and anyone else who wants to know if you are alright. So, you end up dealing with a lot, talking about COVID a lot.” (Male, Aged 30-49).

- “I’m working as a PPE spotter. That’s all I can do […] for the foreseeable future … because I’m still not ready to look after a patient. I don’t have the brain concentration. I don’t have the energy.” (Female, Aged 30-49).

Access to and requirements for vocational rehabilitation and return to work support vary significantly.

- “So the response to COVID by [my] employer has been kind of okay. My husband’s has been appalling. They’re insane and they don’t communicate and their leadership has really been shown up. It’s extremely poor. Disaster. Complete morons, I work at [employer] and they’ve been the total opposite. Absolutely excellent. So the stress associated with the ridiculous behavior of the [husband’s employer] has not helped as well.” (Female, Aged 30-49).

- “I was, when I did come back to work I was offered all the support services, like the counseling people that go through work, I cant remember what their name was but I was offered that as a choice. You know, I could even do that if I still even want to two now, which probably wouldn’t be a bad idea to sort of download it all to someone else other than me”. (Female, Aged 18-29).

- “The support to access [organisation] to get paid OHS leave, those support mechanisms weren’t really there. And even returning to work was quite challenging and I think underappreciated, it’s not just kind of being unwell. There is this sort of stigma, this sort of stigma that does sit with it.” (Male, Aged 30-49).

- “But in terms of at a systems level, they’ve got really no clue from an HR or workplace rehab. I really like our workplace rehab coordinator, but I was offering and sending her information.” (Female, Aged 30-49).

Fears and uncertainties

A complex range of psycho-social factors influences and interact with the lived experience of people recovering from COVID-19. Many people described their fears about Long COVID, some of which related to new symptoms developed following their infection. Study participants also acknowledged they might have become hyper-vigilant about symptoms. Still, they had few ways of checking whether their concerns were reasonable given how little is known about Long COVID. The abrupt disruption experienced by many following acute illness was also traumatic, but few had access to mental health support. An additional contributor to the stress experienced by healthcare workers was a sense of shame for ‘letting themselves’ get infected, given their professional responsibilities to practice good infection control. Other people also discussed the guilt they experienced when they were ‘patient zero’ in their social group, especially if they felt they had passed on the virus to a vulnerable friend or relative. The overall lack of certainty or detailed knowledge about the syndrome was, therefore, very disruptive to their mental health and overall well-being.

Post COVID-19 symptoms can provoke anxiety or be overwhelming.

- “My biggest fear is like choking to death or drowning, something where my oxygen, you know, where I can’t breathe. So, during this sort of process my anxiety level has increased, because the symptoms are mimicking, what I fear most” (Male, Aged 30-49).

- “Now anything that happens like that, we look at it sideways and wonder if it’s COVID”. (Female, Aged 50+)

- “Yeah, it is a massive challenge, and if I had a direction in which to go, rather than just going for test after test, which is what we’ve been doing … you don’t know when it’s going to end”. (Female, Aged 30-49).

Many people recovering from COVID-19 struggle to obtain support for its emotional impact.

- “All these emotions just started coming out, and I didn’t even know I was holding onto it, and I just started crying ‘cause I just said, I just don’t feel myself… he said, “we probably don’t need to go to the point of an antidepressant at the moment, but he said, you know, obviously it’s something on the radar”. (Female, Aged 30-49).

- “There was a lot of talk around lapses in PPE and errors in putting it on and taking it off … it felt like to all of us were kind of shamed and a bit of blame for that. It was our fault for getting infected”. (Female, 30-49)

Stigma and discrimination

The final theme describes the stigma and discrimination many people recovering from COVID-19 have experienced due to their condition or the broader conditions of the pandemic. The following three vignettes illustrate how this experience has continued long after the initial turmoil and confusion of the pandemic had passed.

Conclusion

Two perspectives on the question “What is Long COVID?” have been presented in this chapter – the current knowledge of healthcare researchers and practitioners and the lived experience expertise of patients. Clearly, this syndrome is far more than a collection of commonly co-occurring symptoms. The COVID-19 pandemic has been as much a social phenomenon as a global healthcare emergency, and the knowledge required to engage with its pervasive impact (including Long COVID) originates from multiple disciplines and ways and understanding [46]. Long COVID, in particular, highlights the complex and constant interplay between the multitude of biopsychosocial factors that influence health and well-being. No wonder researchers, healthcare practitioners and patients alike feel overwhelmed.

As highlighted in this chapter, recovering from COVID-19 and Long COVID means different things to different people, and a ‘one size fits all’ approach cannot be applied. Our knowledge of Long COVID is evolving at lightning speed, with multiple new challenges and opportunities always emerging. However, it doesn’t always feel like this for people with Long COVID as much of the progress to date has remained within the research and development realm. Ultimately, Long COVID reminds us of the inherent unpredictability of life and spotlights the limitations of our knowledge. It forces us to confront the fact that sometimes we have to live with uncertainty and discomfort – for the foreseeable future, we will be ‘flying the plane while building it’. [47]. This chapter has, therefore, just scratched the surface of what there is to know and understand about Long COVID … but we all have to start somewhere.

For More Information

The following links will provide you with additional general information about Long COVID from creditable sources. These listings are not exhaustive, and you are encouraged to seek out locally relevant information for your community.

World Health Organisation

Children and Adolescents

A clinical case definition for post COVID-19 condition in children and adolescents

Webinar on Post COVID-19 Condition in Children

Adults

A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition

Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Post COVID-19 Condition Questions and Answers

Australian College of General Practice

Post–COVID-19 syndrome/condition or long COVID: Persistent illness after acute SARS CoV-2 infection

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

References

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C. (2022). Long COVID: Current definition. Infection, 50, 285–286. ↵

- Soriano, J. B., Murthy, S., Marshall, J. C., Relan, P., & Diaz, J. V. (2022). A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 22(4), e102-e107. ↵

- World Health Organisation (WHO). (2021). A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Geneva: WHO. ↵

- Enter your footnote content here. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), & Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP). (2022). COVID-19 rapid guideline: Managing the long-term effects of COVID-19. Version 1.14. London: NICE, SIGN, RCGP. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Long COVID or Post-COVID Conditions 2022 [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/index.html.] ↵

- Stephenson, T., Allin, B., Nugawela, M. D., Rojas, N., Dalrymple, E., Pereira, S. P., ... & CLoCk Consortium. (2022). Long COVID (post-COVID-19 condition) in children: a modified Delphi process. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 107(7), 674-680. ↵

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C., Palacios-Ceña, D., Gómez-Mayordomo, V., Cuadrado, M.L., & Florencio, L.L. (2021). Defining Post-COVID Symptoms (Post-Acute COVID, Long COVID, Persistent Post-COVID): An Integrative Classification. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 2621. ↵

- Ayoubkhani, D., Pawelek, P., & Gaughan, C. (2021). Technical article: Updated estimates of the prevalence of post-acute symptoms among people with coronavirus (COVID-19) in the UK: 26 April 2020 to 1 August 2021. London: Office of National Statistics. ↵

- Caniego-Casas, T., Martínez-García, L., Alonso-Riaño, M., Pizarro, D., Carretero-Barrio, I., Martínez-de-Castro, N., ... & Palacios, J. (2022). RNA SARS-CoV-2 persistence in the lung of severe COVID-19 patients: a case series of autopsies. Frontiers in microbiology, 13, 824967. ↵

- Swank, Z., Senussi, Y., Manickas-Hill, Z., Yu, X. G., Li, J. Z., Alter, G., & Walt, D. R. (2023). Persistent Circulating Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Spike Is Associated With Post-acute Coronavirus Disease 2019 Sequelae. Clinical infectious diseases, 76(3), e487–e490. ↵

- de Melo, G. D., Lazarini, F., Levallois, S., Hautefort, C., Michel, V., Larrous, F., … Lledo, P. M. (2021). COVID-19-related anosmia is associated with viral persistence and inflammation in human olfactory epithelium and brain infection in hamsters. Science translational medicine, 13(596), eabf8396. ↵

- Akiyama, S., Hamdeh, S., Micic, D., & Sakuraba, A. (2021). Prevalence and clinical outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with autoimmune diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 80, 384-391. ↵

- Chang, R., Chen, T. Y. T., Wang, S. I., Hung, Y. M., Chen, H. Y., & Wei, C. C. J. (2023). Risk of autoimmune diseases in patients with COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine, 56, 101783. ↵

- Kondo, M., & Yamanaka, K. (2021). Possible HSP reactivation post-COVID-19 vaccination and booster. Clinical Case Reports, 9, e05032. ↵

- Willyard, C. (2022). Could tiny blood clots cause long COVID’s puzzling symptoms? Nature, 608, 662-664. ↵

- Grant, J.K., Vincent, L., Ebner, B., Hurwitz, B.E., Alcaide, M.L., & Martinez, C. (2020). Early Insights into COVID-19 in Persons Living with HIV and Cardiovascular Manifestations. Journal of AIDS and HIV Treatment, 2(2): 68-74. ↵

- Dou, Q., Wei, X., Zhou, K., Yang, S., & Jia, P. (2020). Cardiovascular manifestations and mechanisms in patients with COVID-19. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 31(12), 893-904. ↵

- Desforges, M., Le Coupanec, A., Dubeau, P., Bourgouin, A., Lajoie, L., Dubé, M., & Talbot, P. J. (2019). Human Coronaviruses and Other Respiratory Viruses: Underestimated Opportunistic Pathogens of the Central Nervous System? Viruses, 12(1), 14. ↵

- Xu, E., Xie, Y. & Al-Aly, Z. (2022). Long-term neurologic outcomes of COVID-19. Nature Medicine, 28, 2406–2415. ↵

- Huang, S., Zhou, Z., Yang, D., Zhao, W., Zeng, M., Xie, X., …. Liu, J. (2022). Persistent white matter changes in recovered COVID-19 patients at the 1-year follow-up. Brain, 145(5), 1830–1838. ↵

- Samper-Pardo, M., Oliván-Blázquez, B., Magallón-Botaya, R., Bartolome-Moreno, C., & Leon-Herrera, S. (2023). The emotional well-being of Long COVID patients in relation to their symptoms, social support and stigmatization in social and health services: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 23, 68. ↵

- Haneef, R., Fayad, M., Fouillet, A., Sommen, C., Bonaldi, C., Wyper, G.M.A. …. Gally, A. (2023) Direct impact of COVID-19 by estimating disability-adjusted life years at national level in France in 2020. PLoS ONE 18(1): e0280990. ↵

- Guzman-Esquivel, J., Mendoza-Hernandez, M. A., Guzman-Solorzano, H. P., Sarmiento-Hernandez, K. A., Rodriguez-Sanchez, I. P., Martinez-Fierro, M. L., Paz-Michel, B. A., Murillo-Zamora, E., Rojas-Larios, F., Lugo-Trampe, A., Plata-Florenzano, J. E., Delgado-Machuca, M., & Delgado-Enciso, I. (2023). Clinical Characteristics in the Acute Phase of COVID-19 That Predict Long COVID: Tachycardia, Myalgias, Severity, and Use of Antibiotics as Main Risk Factors, While Education and Blood Group B Are Protective. Healthcare, 11(2), 197. ↵

- Durstenfeld, M. S., Peluso, M. J., Peyser, N. D., Lin, F., Knight, S. J., Djibo, A., ... & Beatty, A. L. (2023). Factors Associated with Long Covid Symptoms in an Online Cohort Study. Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 10(2), ofad047. ↵

- Wong, M. C. S., Huang, J., Wong, Y. Y., Wong, G. L. H., Yip, T. C. F., Chan, R. N. Y., ... & Chan, F. K. L. (2023). Epidemiology, Symptomatology, and Risk Factors for Long COVID Symptoms: Population-Based, Multicenter Study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 9(1), e42315. ↵

- Abu Hamdh, B., & Nazzal, Z. (2023). A prospective cohort study assessing the relationship between long-COVID symptom incidence in COVID-19 patients and COVID-19 vaccination. Scientific Reports, 13, 4896. ↵

- Hirahata, K., Nawa, N., & Fujiwara, T. (2022). Characteristics of Long COVID: Cases from the First to the Fifth Wave in Greater Tokyo, Japan. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(21), 6457. ↵

- Tam, C. C., Qiao, S., Garrett, C., Zhang, R., Aghaei, A., Aggarwal, A., & Li, X. (2022). Substance use, psychiatric symptoms, personal mastery, and social support among COVID-19 long haulers: A compensatory model. medRxiv, 2022-11. ↵

- Florencio, L. L., & Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C. (2022). Long COVID: Systemic inflammation and obesity as therapeutic targets. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 10(8), 726-727. ↵

- Cazé, A. B. C., Cerqueira-Silva, T., Bomfim, A. P., de Souza, G. L., Andrade Azevedo, A. C., Aguiar Brasil, M. Q., ... & Boaventura, V. S. (2022). Prevalence and risk factors for long COVID after mild disease: a longitudinal study with a symptomatic control group. medRxiv, 2022-09. ↵

- Khan, N., Mahmud, N., Patel, M., Sundararajan, R., & Reinisch, W. (2023). Incidence of Long COVID and impact of medications on the risk of developing Long COVID in a nationwide cohort of Inflammatory Bowel Disease patients, Journal of Crohn's and Colitis, 17 (Supp 1), i392–i393 ↵

- Heubner, L., Petrick, P.L., Güldner, A. et al. (2022). Extreme obesity is a strong predictor for in-hospital mortality and the prevalence of long-COVID in severe COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Scientific Reports, 12, 18418. ↵

- Sudre, C. H., Murray, B., Varsavsky, T., Graham, M. S., Penfold, R. S., Bowyer, R. C., ... & Steves, C. J. (2021). Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nature medicine, 27(4), 626-631. ↵

- Crook, H., Raza, S., Nowell, J., Young, M., & Edison, P. (2021). Long COVID – Mechanisms, risk factors, and management. British Medical Journal, 374, n1648 ↵

- Paul, E., & Fancourt, D. (2022). Health behaviours the month prior to COVID-19 infection and the development of self-reported long COVID and specific long COVID symptoms: a longitudinal analysis of 1581 UK adults. BMC Public Health, 22, 1716. ↵

- Davis, H. E., Assaf, G. S., McCorkell, L., Wei, H., Low, R. J., Re'em, Y., ... & Akrami, A. (2021). Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine, 38, 101019. ↵

- Lopez-Leon, S., Wegman-Ostrosky, T., Perelman, C., Sepulveda, R., Rebolledo, P. A., Cuapio, A., & Villapol, S. (2021). More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific reports, 11(1), 16144. ↵

- Marcovitch, H (Ed). (2017). Black's Medical Dictionary, 43rd Edition. A&C Black. ↵

- Deer, R. R., Rock, M. A., Vasilevsky, N., Carmody, L., Rando, H., Anzalone, A. J., ... & Robinson, P. N. (2021). Characterizing long COVID: deep phenotype of a complex condition. EBioMedicine, 74, 103722. ↵

- Estiri, H., Strasser, Z. H., Brat, G. A., Semenov, Y. R., Patel, C. J., & Murphy, S. N. (2021). Evolving phenotypes of non-hospitalized patients that indicate long COVID. BMC medicine, 19, 1-10. ↵

- Mayor, N., Meza-Torres, B., Okusi, C., Delanerolle, G., Chapman, M., Wang, W., ... & de Lusignan, S. (2022). Developing a Long COVID Phenotype for Postacute COVID-19 in a National Primary Care Sentinel Cohort: Observational Retrospective Database Analysis. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 8(8), e36989. ↵

- Kenny, G., McCann, K., O’Brien, C., Savinelli, S., Tinago, W., Yousif, O., ... & Mallon, P. W. (2022, April). Identification of distinct long COVID clinical phenotypes through cluster analysis of self-reported symptoms. In Open Forum Infectious Diseases (Vol. 9, No. 4, p. ofac060). US: Oxford University Press. ↵

- Zhang, H., Zang, C., Xu, Z., Zhang, Y., Xu, J., Bian, J., ... & Kaushal, R. (2023). Data-driven identification of post-acute SARS-CoV-2 infection subphenotypes. Nature Medicine, 29(1), 226-235. ↵

- Frontera, J. A., Thorpe, L. E., Simon, N. M., de Havenon, A., Yaghi, S., Sabadia, S. B., ... & Galetta, S. L. (2022). Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 symptom phenotypes and therapeutic strategies: A prospective, observational study. Plos one, 17(9), e0275274. ↵

- World Health Organisation. (2021). A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus, 6 October 2021. World Health Organisation. ↵

- Leach, M. (2020). Pandemics are social phenomena, demanding breadth of expertise. WONKHE. Available at https://wonkhe.com/blogs/pandemics-are-social-phenomena-demanding-breadth-of-expertise/ ↵

- Hitch, D. (2023). Long COVID: Why isn't anyone listening? Available at https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2023/8/long-covid-why-isnt-anyone-listening/ ↵

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus (World Health Organisation)

Sustained and persistent symptoms following COVID19 infection which have an impact on a person's quality of daily life.

The physiological functions of body systems (including psychological functions). (ICF, WHO)

Anatomical parts of the body, such as organs, limbs and their components. (ICF, WHO).

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome CoronaVirus 2

The observable characteristics of a disease, resulting from its genetic makeup (genotype) and environmental factors.

The execution of a task or action by an individual (ICF, WHO)

Involvement in a life situation (ICF, WHO)

Personal Protective Equipment

Occupational Health and Safety