Chapter 35: Communicating your findings

Darshini Ayton

Learning outcomes

Upon completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand the important elements to include when communicating your qualitative research.

- Describe approaches to presenting qualitative data.

Formats for communicating qualitative research

It is not uncommon for qualitative researchers to complete data collection and analysis and then to be overwhelmed by the amount of data that has been collected. Presenting data in a meaningful way can be a challenge. Unlike quantitative research, which can use tables, charts and figures to succinctly present research results, qualitative research typically requires a narrative to describe and explain the themes and findings of the research, which may involve the presentation of quotes to illustrate the themes or findings (see Chapter 26).

The main formats for communicating qualitative research are:

- Research thesis – in Australia, examples include honours thesis (approximately 10 months of research, resulting in 10,000–15,000 words); masters thesis (12–24 months of research, 10,000–30,000 words) and doctor of philosophy (PhD) thesis (3–4 years of research, 60,000–90,000 words and may include publications). The benefits of presenting research in a thesis include having the space (word count) and flexibility to write about the qualitative research process and results. For example, in Chapter 26, all the examples about how to write about rigour were from a PhD thesis, which demonstrates that the student was able to write about rigour in greater detail than would have been possible in other formats.

- Conference presentation – typically, the background, methods, results and discussion/ implications of the research need to be demonstrated within a 10–20-minute presentation. Depending on the study, it can be challenging to present all the research in such a short time, and hence researchers often choose to address just one or two of the study’s research questions and focus on the results that address these.

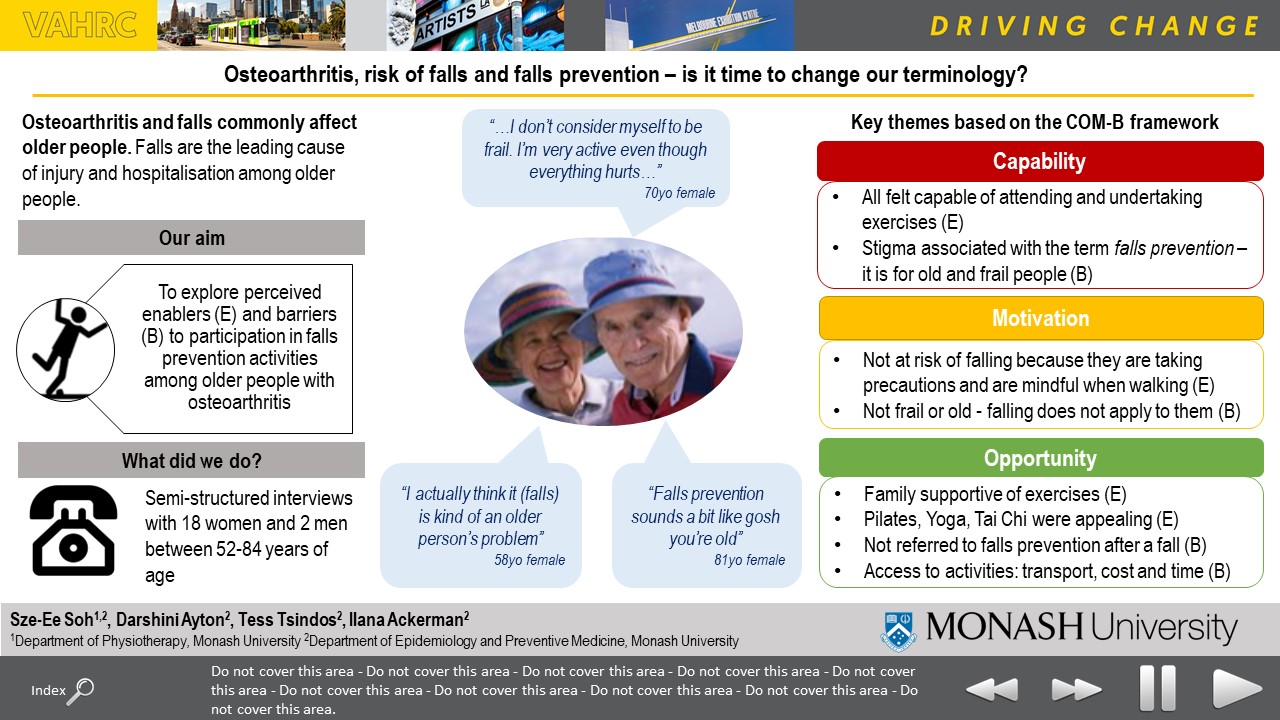

- Poster – a conference poster provides the opportunity to present study results visually, in charts and figures, and to incorporate quotes from participants to illustrate. As with the conference presentation, a poster is limited to providing a high-level summary rather than much detail (see Figure 35.1 as an example).

Figure 35.1: A poster presented at the Victorian Allied Health Research Conference in 2019. Used with permission from the authors.1

- Academic journal or book publication – most researchers wish to publish their research in academic journals and books. Journal requirements differ between disciplines. Throughout the chapters of this textbook, we have provided links to published qualitative research across health and social care journals. These articles demonstrate the diversity of qualitative research in published form. Every journal provides an outline of its focus and scope (see ‘About the Journal’ on the journal’s homepage), including the types of research it is interested in publishing. The Instructions to Authors page guides prospective authors on the types of articles the journal publishes (e.g. original research, opinion, short reports, letters to the editor), word limits, guides to writing style and formatting requirements. Examples of journal websites that provide journal information and author guidance include:

- Health and Social Care in the Community (see the About and Contribute sections)

- BMJ

- Australian Social Work (see the About this Journal and Submit an Article sections)

- Public Health

Styling and formatting qualitative research for publication

The main structure for presenting research in any form is known as IMRAD, which stands for introduction, methods, results and discussion. An outline of each of these sections is provided here, tailored specifically to the presentation of qualitative research:

Introduction

The introduction covers the why of the research by describing the background, research problem, brief literature review, the framework or theory (optional) and posits the research aim and/or question and/or objectives. See, for example:

- Misconceptions and the acceptance of evidence-based non-surgical interventions for knee osteoarthritis. A qualitative study2

- Barriers and challenges affecting the contemporary church’s engagement in health promotion3

Methods

The methods section details the research process (when, where and how the was study done), including the research design and philosophical underpinnings, research setting, population, participant selection, recruitment, data collection, analysis, reflexivity and ethical considerations and approval. As discussed in Chapter 26, it is important to provide enough information about the methods so that the reader can make sense of the results. A useful process, particularly in providing information about data collection, is to include a table showing how data was collected, including relevant activities or questions. See, for example:

- Co-designing a patient support portal with health professionals and men with prostate cancer: an action research study4 (see Table 1)

- Barriers and enablers to intervention uptake and health reporting in a water intervention trial in rural India: a qualitative explanatory study5 (see Tables 1 and 2)

- The primary care experience of adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). An interpretative phenomenological inquiry.6 (The methods section includes a good example of how to write about reflexivity and researcher positionality.)

Results

The results section explains and interprets the data generated from the research. The first part of the results section describes the participants (demographics), dates when data were collected and duration of interviews, focus groups or observations. The next part presents the themes of the study with a narrative, explains the themes of the study and provides supporting quotes. There are several ways themes can be presented: in diagrammatic form, tabular form and/or in narrative form throughout the paper. The decision of how to present the results depend on the journal’s word limit and table requirements. In general, if the word limit is low (up to 3000 words), then quotes tend to be presented in tables. If the word limit is higher (up to 8000 words), then quotes can be woven throughout the results section. See, for example:

- When immunosuppression and COVID-19 intersect: an exploratory qualitative study of young lung transplant recipient perceptions of daily life during a pandemic7 (See supplementary table 1 for the themes and quotes. The results are presented in a narrative format, with an explanation of the theme with quotes in the text.)

- ‘I literally had no support’: barriers and facilitators to supporting the psychosocial wellbeing of young people with mental illness in Tasmania, Australia8 (Figure 1 is a diagram with an overview of the themes.)

As you may observe in the examples given, qualitative researchers do not use percentages when describing themes. Since data collection is flexible and adaptable to the participant group, not all participants may be asked the same questions in the same way. Hence, it is not a structured form of data collection that enables percentages to be presented. While researchers may indicate the number of participants who described a particular experience, they rarely quantify this further; rather, they seek to describe, compare and contrast participants’ responses, using words such as some, others, most, all, a few.

Choosing quotes

The quotes in the narrative presentation and the tables should illustrate the study’s themes. This includes providing ordinary quotes, unexpected quotes, hard-to-classify quotes (or negative case quotes) and minor quotes to illustrate minor themes.

Editing quotes

Quotes from the transcript may be hard to follow and messy to read. Researchers tend to edit quotes for clarity, while being careful to not change the meaning of the quote.

For example, this original, unpublished quote from the 6-PACK pre-implementation study is lengthy, with some statements that are irrelevant to the study’s findings9:

To some extent, some falls are unpreventable… But the majority of times, things can be done to prevent them. Accidents don’t just [happen], you’re walking down the street [and] your high heel breaks, you fall. You can’t say you’re going to prevent that… I think sometimes with some of the elderly that, yes, they’re elderly and they’re demented, but we should be aware that they’re a higher risk of falling and implement things so [they don’t fall]. Having the buzzer close by, having adequate lighting, having adequate railing and stuff around [will help prevent falls]. [unpublished quote]

The same example has been edited; it uses ellipses (…) to indicate when a sentence has been redacted and square brackets to indicate when the researcher has inserted their own words to provide clarity:

To some extent, some falls are unpreventable… But in the majority of times, things can be done to prevent them… yes, they’re elderly and [have dementia], but we should be aware that they’re a higher risk of falling and implement things so [they don’t fall]. Having the buzzer close by, having adequate lighting, having adequate railing and stuff around [will help prevent falls]. [unpublished quote]

Presenting the quotes

If the quote is 40 words or longer, it should be presented as a ‘block quote’, which is an indented paragraph placed after the description of the quote. If the quote is just a few words, it can be integrated into a descriptive paragraph. This can be seen on page 9 of the article by Ayton and colleagues on the pre-implementation study of the 6-PACK falls prevention intervention.9 The bold text in the block quote following indicates the theme and the bold text in italics indicates a subtheme. Quotes in italics (or within a single quotation mark) are woven into the explanation of the theme. The final quote is presented separate from the main text as it is longer and brings together the points that have been made in the descriptive paragraph.9

Engaging staff in falls prevention. As highlighted by one senior staff participant, staff engagement is important and can be facilitated through ‘engaging hearts and minds’—both the emotional and logical aspects of falls prevention. Nurses described feeling guilty, stressed and distressed when a patient under their care experienced a fall. They also described the worry experienced if a patient suffered a fall-related injury. The emotional impact of a patient fall was seen as something that could be a motivating factor. A senior staff member at one hospital highlighted that nurses responded to interventions that emphasised the benefit to the patient. This also had implications for sustaining the project long term:

If you always promote it as best for the patient and patient-focused you’ll get staff on-board, and continuing to help drive the program. You’ve got to be able to sell it to them… first of all say this is going to be so much better for your patient outcomes. (SS1, H1)9(p10)

Discussion

The discussion section revisits the study’s aims, research questions and objectives and then presents the implications of the results within the context of the broader academic literature base. The discussion also includes the strengths and limitations of the study, and implications of the study or future research directions. In some social science journals and book, the results and discussion sections may be combined. See, for example:

- Boundary breaches: the body, sex and sexuality after stoma surgery10 (The results and discussion are presented together with concluding remarks at the end.)

- Exploring the partnership networks of churches and church-affiliated organisations in health promotion2 (The results and discussion are combined, including the section on strengths and limitations, with a conclusion at the end. This paper also provides a good example of the use of diagrams.)

In the discussion section, it is important to demonstrate that the research questions and aims have been addressed. Some researchers adopt their research questions as subheadings in the discussion. The discussion positions the research within the research discipline and published research, and presents research implications.

Considerations in determining publication of qualitative research

- Explore different journal types. Look at the reference list you have included in your paper and note which journals are mentioned often. This will provide a good rationale for submitting to one of those journals.

- Research the journal. Once you have chosen a journal to submit to, consider whether it has published qualitative research. Does it have reviewers or an editorial board member who is experienced in qualitative research? Read the author guidelines closely for guidance on submitting qualitative research, in terms of word limits, presentation style and reporting tools required (see Chapter 36 for details on reporting tools).

- Check the journal’s data–sharing requirements. Consider whether you can ethically meet these requirements. For example, Plos ONE requires authors to make their raw, de-identified data available (see https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/data-availability)

- Find an example to guide your submission. After you have identified the journal you wish to submit your paper to, find a qualitative research article that has been recently published in that journal (it does not need to be in the same topic area as your research). Use this article as a template to guide how you prepare your introduction, methods, results, discussion and conclusion.

- Persevere. It is not unusual to have to submit to a few journals before finding the right home for your article. Take on reviewer feedback (see Chapter 37) and seek advice from colleagues and peers about where to submit.

Summary

Communicating qualitative research requires the researcher to consider the form of communication and to tailor the data, results and presentation to suit the format (thesis, conference presentation, journal paper) and the needs of the audience. When presenting qualitative research, typically the IMRAD format is followed. Considering how to present data – whether in narrative form or using tables and diagrams – is often contingent on the journal’s requirements.

References

- Soh SE, Ayton D, Tsindos T, Ackerman IN. Osteoarthritis, risk of falls and falls prevention – is it time to change our terminology? Presented at: Victorian Allied Health Research Conference; 2019; Melbourne, Australia.

- Bunzli S, O’Brien P, Ayton D, et al. Misconceptions and the acceptance of evidence-based nonsurgical interventions for knee osteoarthritis. a qualitative study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477(9):1975-1983. doi:10.1097/CORR.0000000000000784

- Ayton D, Manderson L, Smith BJ. Barriers and challenges affecting the contemporary church’s engagement in health promotion. Health Promot J Austr. 2017;28(1):52-58. doi:10.1071/HE15037

- Shemesh B, Opie J, Tsiamis E et al. Codesigning a patient support portal with health professionals and men with prostate cancer: an action research study. Health Expect. 2022;25(4):1319-1331. doi:10.1111/hex.13444

- McGuinness SL, O’Toole J, Ayton D et al. Barriers and enablers to intervention uptake and health reporting in a water intervention trial in rural India: a qualitative explanatory study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;102(3):507-517. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.19-0486

- Madawala S, Warren N, Osadnik C, Barton C. The primary care experience of adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). An interpretative phenomenological inquiry. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(6):e0287518. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0287518

- Hatzikiriakidis K, West S, Ayton D, Morris H, Martin RS, Paraskeva M. When immunosuppression and COVID-19 intersect: an exploratory qualitative study of young lung transplant recipient perceptions of daily life during a pandemic. Pediatr Transplant. 2022;26(5):e14281. doi:10.1111/petr.14281

- Savaglio M, Yap MBH, Smith T, Vincent A, Skouteris H. “I literally had no support”: barriers and facilitators to supporting the psychosocial wellbeing of young people with mental illness in Tasmania, Australia. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2023;17(1):67. doi:10.1186/s13034-023-00621-y

- Ayton DR, Barker AL, Morello RT et al. Barriers and enablers to the implementation of the 6-PACK falls prevention program: a pre-implementation study in hospitals participating in a cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0171932. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171932

- Manderson L. Boundary breaches: the body, sex and sexuality after stoma surgery. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(2):405-15. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.051