Authentic Assessment

Exploring “What if . . .?” with Renewable Assignments

University of Southern Queensland

Dr Eseta Tualaulelei

Overview

What if university assignments contributed to the greater good? What if students had a genuine audience for their assignment work rather than just a faculty member or two? What if our students could contribute to their future professions while at university developing their professional knowledge? This chapter describes an open educational practice called ‘renewable assignments’ (Wiley, 2016) and how it was used to explore these three questions. I am a senior lecturer in the School of Education at a mid-sized regional university in Australia. From 2019 to 2023, I and my colleague Dr Yosheen Pillay conducted and researched renewable assignments in projects that led to 91 students contributing to 4 online books of open educational resources (OER). In this chapter, I explain the ins and outs of the project and provide some advice from my experiences. The chapter begins by outlining the different groups of people involved in the project – including open education support staff, pre-service teachers, in-service teachers, and university educators – before explaining the project’s rationale. This is followed by a detailed explanation of how renewable assignments were implemented across undergraduate and postgraduate courses in Education at a mid-sized regional university in Queensland, Australia. The explanation includes details about how action research was built around the activities to ensure that data about specific impacts were captured. In this case, the action research focused on student engagement for two cycles and on graduate employability for another two cycles, and it produced a range of insights into how renewable assignments impact on student experiences. The chapter ends with some recommendations for those interested in running renewable assignments in their own courses and reflections from people who were involved.

Using this case study

Renewable assignments are a type of authentic assessment that can engage students with online learning and enhance their graduate employability. After reading this chapter:

- Academic staff will: Develop awareness of the benefits and processes for facilitating quality student renewable assignments to be published as an OER.

- Library staff will: Learn strategies and techniques for working with students and academics to publish high quality student created content.

Key stakeholders

Open education support staff: My university is lucky to have a unit solely devoted to open education initiatives. The two staff members of this unit at the time, Dr Adrian Stagg and Ms Nikki Andersen, were integral to conceptualising, supporting and promoting the project. Adrian is an open education expert and Nikki is a librarian specialising in inclusion and copyright so they were able to answer any questions we had about open publishing.

Our students: 91 students (pre-service and in-service teachers studying the Bachelor of Education, Master of Learning and Teaching and Master of Education – Guidance and Counselling) took the leap of faith to publish their university assignments openly.

In-service teachers: Teachers who are currently teaching in early childhood centres, primary schools and secondary schools contributed to the conceptualisation and review of the OER.

University educators: I teach early childhood and primary courses in intercultural education and literacy teaching and Yosheen teaches Educational Guidance and Counselling. I ran three cycles of the project in my courses and Yosheen ran one cycle in her course.

Background information

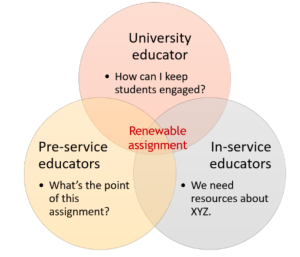

Several different needs were addressed with renewable assignments. Figure 1 shows the juncture at which the renewable assignment was located and how it responded to various stakeholder needs, including:

Pre-service educators: In every course, we hear from students how they feel about their learning and their university experiences. One of the top areas of complaint are university assignments, their expectations, their relevance to the real world and the skills and knowledge students are meant to learn from them. University assignments are often designed with professional expectations and university standards in mind, but often they disregard students’ perspectives. Renewable assignments offered an authentic assessment task, linked directly to contemporary practice, that developed research and presentation skills students would use when they became teachers.

University educators: We are constantly looking for improved ways to support and encourage student learning. The first iteration of this project came about in part because of my dissatisfaction with an assignment I had inherited that I thought was not conveying key concepts and ideas in a meaningful way. Renewable assignments offered an avenue for thinking outside the box about how I could improve this particular assignment for students and strengthen the links between what we were doing at university and the teaching profession.

In-service teachers: In professional development sessions I have run over the years, teachers have expressed their need for resources. While the internet provides an endless array of resources, their quality and relevance varies. In an area such as intercultural education, place-based and local resources are more valuable than generic ones. Similarly, in literacy teaching, techniques, ideas and methods are constantly being updated and explored. The busy literacy teacher does not have time to keep on top of all these developments but me and my students do. I saw an opportunity to infuse this knowledge into resources that could be shared with the profession.

Project description

Renewable assignments are those that “both support an individual student’s learning and result in new or improved open educational resources that provide a lasting benefit to the broader community of learners” (Wiley & Hilton, 2018, p. 137). They are a type of authentic assessment that is shared publicly with an open license. Mindful that there are different approaches to renewable assignments, I will explain my specific project through three different processes: running a renewable assignment, involving professionals and how to research your project.

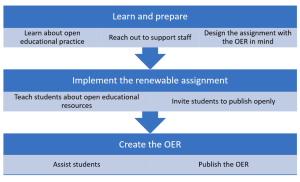

Running a renewable assignment

Learn and prepare: I was a complete novice to open education but the academic literature is accessible and high quality. I tried to learn as much about open education and open educational resources as I could. Support staff were invaluable as they provided insights into a range of matters (digital platforms to host the OER, open licenses, technological advice, copyright requirements for multimedia etc.). What I learned in this stage helped me to design and visualise the OER that my students would produce. When preparing the assignment instructions for students, I mentioned the possibility of their work being openly published. As I didn’t know whether a student would pass the assignment or the course overall, open publishing was only mentioned as a possibility and resources were shared for their educative value.

Implement the renewable assignment: I ran the assignment as I usually would in a course. In later iterations, I integrated resources into the course about open education; the United Nations (2019) actually recommends that this knowledge is incorporated in all initial teacher education courses. After the course had finished and grades were finalised, I invited students who has passed both the assignment and the course to contribute to the open publication. I was not concerned with whether the students achieved a low or high grade; so long as they passed, they were invited to contribute a chapter to the online book.

Create the OER: Those who accepted the invitation were given guidance with the purpose of the book and who the audience was (in-service teachers). They could publish their assignment artefact exactly as they had submitted it or they could modify it as they wished. Students were advised, however, that all chapters would be edited for accuracy and readability. With later books, students were given a template for their chapter so that the OER would present as a cohesive collection. Before these projects, I had never published and edited a collection of anything so this was a useful training ground for that whole process. For each book I worked with a co-editor and the open education support staff.

Involving in-service educators or professionals

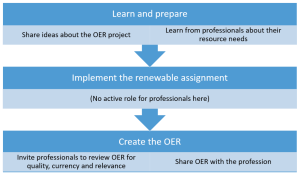

Learn and prepare: We offered professional development to early years educators and guidance counsellors to share ideas about the OER project and gather their insights. For instance, we learned that educators were drawing from Department of Health resources because the Department of Education did not have what they needed. We learned about the types of day-to-day concerns that guidance and counselling professionals wanted guidance with. In particular, we learned about the profession’s resource needs, particularly because we wanted to create OER that would be useful and contribute positively to professions.

Implement the renewable assignment: There was no active role for professionals in this stage as implementation was an internal course activity.

Create the OER: Quality is often a concern about student-generated OER (Wiley et al., 2017), so we invited professionals to review the chapters. They were asked to comment on the currency, quality and relevance of the work and in two of our books, we openly published excerpts from these reviews. The OER were shared back with the professionals who helped conceptualise our projects and they have been shared more widely across the teaching profession as well.

Figure 3. Summary of steps for involving in-service educators or professionals

Researching renewable assignments

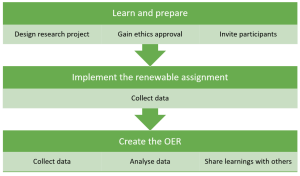

Learn and prepare: I designed my project with the intention of researching it from the outset because this was a new teaching practice for me and I wanted to know what impacts, if any, it would have for my students. Utilising the pragmatic approach of action research, I designed tools to collect data through surveys, semi-structured interviews and researcher reflections. We gained ethics approval and then invited students to participate. In the early cycles of the project, students were invited to participate while they were creating the OER, but in later cycles, we were interested in knowing what students knew about open education so we invited them earlier in the process.

Implement the renewable assignment: While the assignment was being implemented we collected data as teacher educators, reflecting on the process of integrating knowledge about open education in our courses.

Create the OER: Surveys and semi-structured interviews were conducted after the OER were published. Once data were analysed, we shared our learnings at various conferences and our students presented alongside us at some of these (see next section).

Key outcomes

A total of 91 students published four online books:

- Gems and nuggets: Multicultural education for young children (Tualaulelei & Hawkins, 2020)

- Hidden Treasures: Intercultural resources for early years educators (Tualaulelei & Macdonald, 2021)

- Hearts and minds: Mental health support for schools (Pillay & Tualaulelei, 2022)

- Co-creating multimodal texts with young children (Tualaulelei & Pillay, 2023)

Student-authors Katelyn Jackson, Kim Rohde, Sophie Woodward and Jillian Stansfield presented with Yosheen and I at our university’s 2022 Open Week to celebrate open education. I also presented with Sophie at the Australian Literacy Educators Association Digital Energy Symposium 2023 and again in 2023 for that association’s Teacher Education Special Interest Group.

I found evidence that renewable assignments increased student engagement (Tualaulelei, 2020) and enhanced some graduate attributes (Tualaulelei & Pillay, 2022). Our findings have also been shared through university events, teaching and learning blogs and professional development.

In 2021, OEGlobal gave me a UNESCO OER Implementation Award for collective impact and for demonstrating exemplary leadership in advancing the UNESCO Open Education Resource Recommendation in our own practices (there were 294 global recipients for this award). In 2022, the Special Issue for the Journal of Multicultural Education edited by Stacy Katz and Jennifer Van Allen that included our article Tualaulelei and Green (2022) won an OEGlobal Open Research Award.

What’s next for this project is more dissemination of the practice of renewable assignments and of the project’s findings.

Learnings and recommendations

Work in teams: I did the first two cycles of this project as an individual and this was difficult. Working in a team of two or more people is recommended to help manage time and effort. I collaborated with two early years experts, Karen Hawkins and Jacqueline Macdonald, to help me edit the first two volumes of OER and later worked with Yosheen Pillay. This helped lighten the load because there was a lot of decision-making involved in each project.

Use available support: Academics are usually quite busy with a range of work. To keep your project moving forward, draw upon the expertise of others, particularly open education support staff, librarians and anyone else who can help you. For example, Yosheen had the university photographer assist her creating the cover of Mental Health for which she had a specific idea in mind (those are her hands that are artfully arranged on the cover).

Work ethically: There are times when open publication is appropriate and times when it is not (Orozco, 2020) and it helps to be aware of these. Try to think about your students and their best interests so that they do not produce OER that may impact them negatively.

Share your project and learnings: In looking for guidance, the only academic source I could find several years ago was a thesis by Dr Mais Fatayer that described something similar to what I wanted to do. There are far more resources available now but more are always welcome. Sharing your work helps others.

Champions

Student feedback:

- I was very excited to be published. It is an honour to be recognised for our research and expertise.

- It was very exciting to contribute to a profession which I will soon be a part of as well as sharing with family and friends the work which I have been doing (you do not get this opportunity often as an adult).

- Amazing idea! Amazing to be a part of . . . Most importantly, it is an excellent collaborative action and a great resource. I have never seen this done before.

Early years educator feedback: “I like that there is a variety of information available. I feel that the information given is informative and valued. I also like that other educators can share their knowledge also.” (Elena Weatherall, Swallow Street Child Care Association)

In this promotion video for Hidden Treasures, you’ll hear Liza Corrie (former pre-service teacher) talk about her experiences with our project.

In practice

Advice for future projects: Do it! This chapter has only scratched the surface of the benefits this project had for everyone involved. As a teacher educator, I’m more aware of the immense experience our students bring with them to our courses; our students feel validated and accomplished; and early years educators and teachers can access our resources that respond specifically to their concerns.

Acknowledgement of peer reviewers

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following people who kindly lent their time and expertise to provide peer review of this chapter:

- Nicole Gammie, Senior Learning Librarian, La Trobe University Library, La Trobe University

How to cite and attribute this chapter

How to cite this chapter (referencing)

Tualaulelei, E. (2024). Exploring “What if . . .?” With Renewable Assignments. In Open Education Down UndOER: Australasian Case Studies. Council of Australian University Librarians. https://oercollective.caul.edu.au/openedaustralasia/chapter/exploring-what-if-with-renewable-assignments

How to attribute this chapter (reusing or adapting)

If you plan on reproducing (copying) this chapter without changes, please use the following attribution statement:

Exploring “What if . . .?” With Renewable Assignments by Dr Eseta Tualaulelei is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

If you plan on adapting this chapter, please use the following attribution statement:

*Title of your adaptation* is adapted from Exploring “What if . . .?” With Renewable Assignments by Dr Eseta Tualaulelei, used under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

References

Orozco, C. M. (2020). Informed open pedagogy and information literacy instruction in student-authored open projects. In A. Clifton, K. D. Hoffman, R. I. Berkman, E. Daly-Boas, L. E. J. Easterly, M. Garcia, D. F. Rossen-Knill, & K. Totleben (Eds.), Open pedagogy approaches: Faculty, library, and student collaborations. Milne Publishing/Pressbooks. https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/openpedagogyapproaches/chapter/informed-open-pedagogy-and-information-literacy-instruction-in-student-authored-open-projects/

Pillay, Y., & Tualaulelei, E. (Eds.). (2022). Hearts and minds: Mental health support for schools. Pressbooks. https://usq.pressbooks.pub/heartsandminds/.

Tualaulelei, E. (2020). The benefits of creating open educational resources as assessment in an online education course. In S. Warburton & S. Gregory (Eds.), Australiasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education [ASCILITE] 37th International Conference on Innovation, Practice and Research in the use of Educational Technologies in Tertiary Education (pp. 282-288). University of New England. https://2020conference.ascilite.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/ASCILITE-2020-Proceedings-Tualaulelei-E.pdf

Tualaulelei, E., & Green, N. C. (2022). Supporting educators’ professional learning for equity pedagogy: The promise of open educational practices. Journal for Multicultural Education, 49(1), 99-122. https://doi.org/10.1108/JME-12-2021-0225

Tualaulelei, E., & Hawkins, K. (Eds.). (2020). Gems and nuggets: Multicultural education for young children. Pressbooks. https://usq.pressbooks.pub/gemsandnuggets1/.

Tualaulelei, E., & Macdonald, J. (Eds.). (2021). Hidden Treasures: Intercultural resources for early years educators. Pressbooks. https://usq.pressbooks.pub/gemsandnuggets2/.

Tualaulelei, E., & Pillay, Y. (2022). How can renewable assignments enhance students’ graduate attributes? Insights from an action research project. In S. Wilson, N. Arthars, D. Wardak, P. Yeoman, E. Kalman, & D. Y. T. Liu (Eds.), 39th International Conference on Innovation, Practice and Research in the Use of Educational Technologies in Tertiary Education (ASCILITE 2022) (pp. e2221071-e2221076). Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education (ASCILITE). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14742/apubs.2022.107

Tualaulelei, E., & Pillay, Y. (Eds.). (2023). Co-creating multimodal texts with young children. Pressbooks. https://usq.pressbooks.pub/multiliteracies/.

UNESCO. (2019). Recommendation on Open Educational Resources (OER). UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373755/PDF/373755eng.pdf.multi.page=3

Wiley, D. (2016, July). Toward Renewable Assessments. Improving learning. https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/4691

Wiley, D., & Hilton, J. (2018). Defining OER-enabled pedagogy. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(4), 133-147. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v19i4.3601

Wiley, D., Webb, A., Weston, S., & Tonks, D. (2017). A preliminary exploration of the relationships between student-created OER, sustainability, and students’ success. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(4), 60-69. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i4.3022