Creation

Envirocare: A Collaborative Approach to Integrating Indigenous Ways of Knowing, Being and Doing into Curricula with a Digital Learning Space

Deakin University

Amanda K Edgar; Lea Piskiewicz; Sureikha Ratnatunga; Anthony Neylan; Ruary Ross; Dr Shannon Kilmartin-Lynch; Paris Beasy; and Dr Angela Ziebell

Content Advisory: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cultural Material

Please be aware that the following content may include photos featuring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who have passed. Viewer discretion is advised, and sensitive viewers are encouraged to take this into account before proceeding.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Traditional Owners of all the lands, skies and waterways across this country. We would like to express gratitude to those that participated in interviews for Envirocare and reviewed the product that have kindly helped us to disseminate their messages. Additionally, we want to thank the Traditional Custodians of this land for Caring for Country and recognise that this land (never ceded) would not be the country it is now without thousands of generations of First Nations Peoples having cared for Country.

Overview

There is a persistent gap in the understanding of Australia’s First Nations peoples’ culture and histories across Australia. This chapter presents the development of Envirocare, a digital learning space developed to support the integration of cultural intelligence and the appreciation of First Nations science into science curricula across Australian universities using the lens of Caring for Country. We present the design process of an equitable open access and sustainable space that provides choice to study at any time and at any pace, while meaningfully supporting culturally appropriate content.

The journey developing Envirocare brings together third space professionals and academics, a teaching academic, a dean’s council, young First Nations scientists, a First Nations advisory board, and 9 members of Community. We aimed to fill a resource gap at the classroom level where many educators feel unable to build their own resources either because they are resource and time poor, or they feel ill-prepared. Together, these groups and individuals have been able to meet the overarching goal of producing a resource for developing capabilities in cultural intelligence and Indigenous science, including a nascent understanding of First Nations ways of knowing, being and doing. We privilege representation from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders through stakeholder consultations with the advisory committee of First Nations rangers and educators, video interviews with the Community members, and content generation by First Nations scientists and educators.

The following is a case study that highlights the capability of embedding First Nations perspectives, through the lens of third space professionals and academics, to emphasise the opportunity for using open access to promote cultural intelligence in higher education with digital learning spaces. We acknowledge that there will never be enough space to tell all stories, but we hope that through the bringing together of these shared stories we can foster a desire for learners and educators to continue to grow.

Key stakeholders

The development of Envirocare relied on the establishment of an interdisciplinary partnership. This was initiated by the Australian Council of Environmental Deans and Directors (ACEDD) and hosted by Deakin University, with a co-design approach to incorporate many voices of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islanders.

Background

To enhance social justice and address inequalities there is a growing emphasis on ensuring graduates have the capabilities to work with and for First Nations peoples (Page, Trudgett and Bodkin-Andrews, 2019; Brinkmann, 2014). As such, Universities Australia supports higher education curricula to have Indigenous science embedded as an important step towards decolonisation of the curriculum (Universities Australia, 2022). This chapter suggests how this might be achieved in the current context: 1) where First Nations Australians are underrepresented in higher education, and 2) where non-First Nations educators are involved in respectfully designing and delivering Indigenous science curricula (Cooper et al., 2024).

First Nations science and knowledges are intimately linked to place/location, the science and knowledge is generated at that location to understand and to respectfully live in that location. Those designing First Nations curricula should generally ensure that the importance of place-based knowledge and knowledge systems is recognised and incorporated into learning (Ens et al., 2015). Therefore, here is a potential for tension to arise where a national resource is attempted. A nationwide approach, may automatically conflict with recognising that knowledge is place-based. However, the utility of a national resource delivering basic introductory content and skills was enough for the developers to attempt to walk this fine line between scalability and place-based learning.

Envirocare was deliberately designed to find a balance in respecting place-based knowledge and scalability. Envirocare does this by embracing the diversity of peoples in Australia and their shared value of Caring for Country to showcase Indigenous science and support cultural intelligence through reflective activities. Envirocare consciously avoids teaching deeper content which should generally be place-based. The role of teaching specific place–based knowledge is left to the local academics. We aim for Envirocare to be a solid introductory resource so that those local academics can focus on adding learning that does vary with place, degree and student learning level.

Reflections from third space workers

From the lens of working in the third space we share our reflections on developing Envirocare and the impact that this had on our personal and professional development. For example,

“Some instances of things…I didn’t know at all.” – project team member.

This collaboration allowed us to share experiences and reflect on how our involvement impacted our own cultural intelligence. Being part of the project, gave us the opportunity to engage in and with First Nations culture.

“…there are a lot of things that I didn’t know, and that I’m learning… it is an interesting experience and exciting, there’s not that many other opportunities to meet it, and to interact with the culture and to interact with First Nation’s people directly.” – project team member.

We were developing a space for learning, and with that space, we developed, learning about the diversity of First Nations groups and the richness of that diversity.

“We thought some plants were native when they were not, or we gathered image of a sacred dance which we learned that it’s actually not okay to share, because a sacred dance is meant for certain eyes only and not to be shared widely.” – project team member.

The reflections on our own realities moved our identities, our perceptions of the world and perceptions of what students could be learning through completing the modules.

“…and it’s a beautiful experience.” – project team member.

Our experience of learning about culture was through being involved in a collaborative project, which fostered relationships that encouraged interaction and though feedback, helped build our confidence in building First Nations learning material for students. This development of the resource allowed us to feel as if we gained a level of expertise in producing resources which privilege representations of First Nations peoples.

“…getting that guidance from them is very rich and fairly unique.” – project team member.

Guidance from First Nations peoples gave us confidence in what we were creating. By the end of the project, we developed a sense that we were a vessel for what they wanted, and needed to be created, to spread their messages. This was not just through multiple levels of collaboration, but it was through shared respect, and our natural inquiry to understand and learn.

How was Envirocare developed?

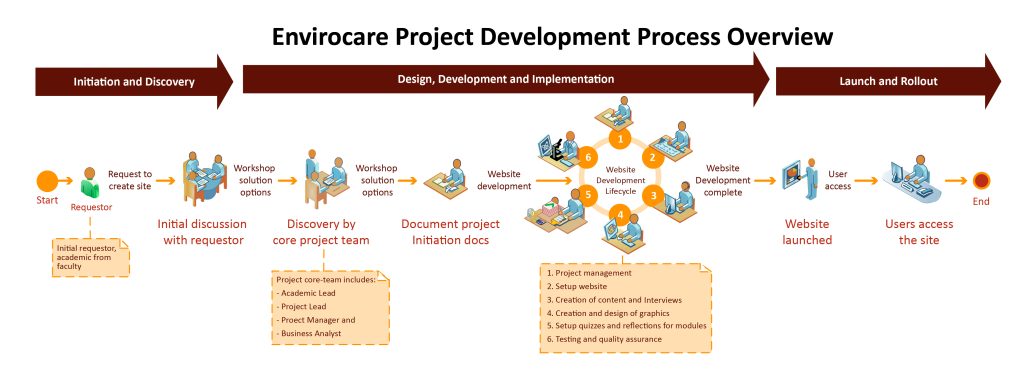

The creation of Envirocare brought complex dialogue and decisions about inclusion, representation, access and learning design (see Figure 1). These were approached with implicit openness from the project team, leading to enrichment of the digital learning space as well as personal development. The methodology for this collaborative process is described below.

Developing a framework for the digital learning space

The project team at Deakin University, with some experience in developing Indigenous knowledge learning resources with First Nations peoples in the university setting, recognised the broader pedagogical value of collaborating broadly to produce a national open access digital learning space. The team at Deakin University identified how to host a digital learning space that could allow sharing of knowledge through open access, a key challenge in the project. This platform could offer a safe learning space that featured interactive self-assessments, self-reflections and ability for students to evidence learning.

The development of the digital learning space was supported by weekly project team discussions, which brough opportunities to reflect on the projects aims and the content of Envirocare. These meetings allowed the team to assess how existing infrastructure, and systems enable these types of projects or hindered their development. Regular discussions enabled the team to evaluate the impact of this work, refine the narrative being conveyed, and explore opportunities to deepen the knowledge of the project team members.

Strategy for designing learning

The learning was designed through a collaboration between a teaching academic, the Academic Lead, Learning Designers and Indigenous Strategy and Engagement team from Deakin University and external First Nations experts. The learning design approach aimed to:

- Help student understand how their own culture and experiences influences their life and beliefs,

- Teach about the impact of colonisation including the continuing impacts,

- Introduce a large range of First Nations voices to the students,

- Ensure the resource was culturally safe for First Nation’s students,

- Teach about Indigenous science concepts that are relevant to all science students in Australia,

- Be majority written and spoken by First Nations peoples.

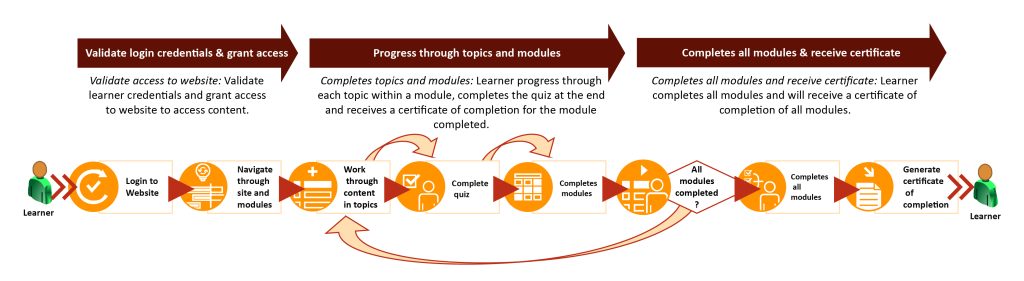

Techniques for visualisation

The graphical design for Envirocare considered how to capture diverse representation from across Australia in the visual appearance of the learning space. In doing so, the designers took inspiration from going onto Country and exploring the native flora and fauna (see Figure 2).

The visual assets that evolved demonstrate a holistic interdependence between the First Nations peoples and the environment, serving as a reminder of the deep cultural connections and responsibilities that First Nations peoples have with Country, set against the backdrop of diverse Australian landscapes.

Key outcomes

The key outcome for the project was the development of a national open access digital learning space, Envirocare, that could be accessed by students from universities across Australia to learn about Caring for Country (Figure 3). The digital learning space hosts four asynchronous modules that educators can use to support learning already happening in their class, to help students prepare for on-Country experiences, to add an element of Indigenous science which they use for assessment, or to offer students additional optional learning.

To be inclusive, modules can be completed at any time, any place, in any sequence and from anywhere with internet connection (Ciasullo, 2018). Once the modules are completed a certificate of completion is produced, per module or for the entire Envirocare content. The certificate can be submitted as evidence of attainment of the learning outcomes provided by Envirocare. This is being piloted with environmental science students and following national access the next stages are to understand how this can be embedded within curriculums and to understand the impact of such a resource.

In practice

Initially, the project seemed quite challenging, and to overcome this we brought together a strong team with a varied experience to create something that was unique. The project team focused on the quality of the product, rather than meeting short turnaround times, to ensure that what was produced gave voice and representation to First Nations peoples participants. This required utilising existing networks and building relationships over three years.

The project team aimed to create content, graphics, videos and text through an inclusive process to ensure that diversity was brought into the final product and represented examples of diversity (Edgar et al., 2024). This concerted effort towards creating engaging and informative content was aimed to accurately reflect Caring for Country.

The challenges that the project team faces were overcome by the interdisciplinary approach. This enabled collaborative discussions that touched on the technical and creative challenges faced during the website’s development, including language use, content accuracy, and interface design. It also ensured specific roles were defined with an emphasis on ensuring that team members contributed effectively to their areas of expertise, highlighting a structured approach to project management.

Image descriptions

Figure 1: Process map of the development of Envirocare

Initiation and Discovery

- Requestor started the process

- Project team request to create site

- Initial discussion with requestor and project team

Design, Development and Implementation

- Workshop options for a solution

- Discovery process was conducted by core project team

- Document project initiation document

- Website development

- Website development lifecycle includes:

- Project management

- Setup website

- Creation of content and interviews

- Creation and design of graphics

- Setup quizzes and reflections for modules

- Testing and quality assurance

- Completes website development

Launch and Rollout

- Website launched

- User access the site

- End of process

Figure 2: The creation of visual assets for the digital learning space

This composite image consists of five horizontally displayed panels, each describing a different step in a process involving illustrating native plants and fauna of Australia. It is a Five-step process involving native plants and fauna. Images show native plants, cyanotype creation, digital plant illustrations, and animal sketches with a frog photo.

- First Panel (Far Left) Step 1 Gathering native plants on country and drying them:

- Overview: Close-up photograph of yellow flowering native plants.

- Details: Bright yellow, elongated flower clusters amidst green leaves.

- Second Panel, Step 2 Exposing the leaves to the sun to create a cyanotype:

- Overview: Several pieces of leaves and flowers arranged on white rectangular papers, exposed to sunlight.

- Details: Each paper holds different plant sprigs, including leaves and small flowers, positioned on a concrete surface.

- Third Panel, Step 3 Developing the cyanotypes:

- Overview: A cyanotype image showing white silhouettes of plants on a blue background, on a sheet of paper.

- Details: Different plant shapes are outlined in white, contrasted sharply against the deep blue.

- Fourth Panel, Step 4 Creating the digital assets:

- Overview: Illustrations of various plant species, digitally scanned and recoloured.

- Details: Displayed in different colours including yellow, red, orange, and black. The plants are stylized and scattered across the white background.

- Fifth Panel (Far Right) Step 5 Drawing native fauna:

- Overview: Combined image featuring animal sketches and a photograph.

- Details: Upper part shows sketches of birds and fish in thin red-orange lines. The lower part features a clear, close-up photograph of a frog perched on brown grass, with a white outline drawing of the same frog.

Figure 3: Demonstrates the students learning journey through Envirocare

Validate login credentials and grant access

- Learner: starts with validating login credentials to grant access

- Login to website: validate access to the website

- Navigate through site and modules: progress through topics and modules

Progress through topics and modules

- Work through content topics: completes reflections and quiz items in module

- Complete quiz: completes quiz at end of each module

- Complete modules: receive a certificate of completion for each module.

Completes all modules and receive certificate

- Completes all modules: completes all modules

- Final Certificate: after completing all modules, learner receives certificate of completion.

References

Ciasullo, A. (2018). Universal design for learning: The relationship between subjective simulation, virtual environments, and inclusive education. Research on Education and Media, 10(1), 42-48. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45381107

Cooper, G., Fricker, A., & Gough, A. (2024). Promoting First Nations science capital: Reimagining a more inclusive curriculum. International Journal of Science Education, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2024.2354077

Edgar, A. K., Tai, J., & Bearman, M. (2024). Inclusivity in health professional education: How can virtual simulation foster attitudes of inclusion? Advances in Simulation, 9(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-024-00290-7

Ens, E. J., Pert, P., Clarke, P. A., Budden, M., Clubb, L., Doran, B., Douras, C., Gaikwad, J., Gott, B., & Leonard, S. (2015). Indigenous biocultural knowledge in ecosystem science and management: Review and insight from Australia. Biological Conservation, 181, 133-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.11.008

Universities Australia. (2022). Universities Australia Indigenous strategy 2022-25. https://universitiesaustralia.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/UA-Indigenous-Strategy-2022-25.pdf

Acknowledgement of peer reviewers

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following people who kindly lent their time and expertise to provide peer review of this chapter:

- Lisa Grbin, Open Education Librarian, Deakin University

How to cite and attribute this chapter

How to cite this chapter (referencing)

Edgar, A. K., Piskiewicz, L., Ratnatunga, S., Neylan, A., Ross, R., Kilmartin-Lynch, S., Beasy, P & Ziebell, A. (2024). Envirocare: A Collaborative Approach to Integrating Indigenous ways of Knowing, Being and Doing into Curricula with a Digital Learning Space. In Open Education Down UndOER: Australasian Case Studies. Council of Australian University Librarians. https://oercollective.caul.edu.au/openedaustralasia/chapter/envirocare-a-collaborative-approach

How to attribute this chapter (resuing or adapting)

If you plan on reproducing (copying) this chapter without changes, please use the following attribution statement:

Envirocare: A Collaborative Approach to Integrating Indigenous ways of Knowing, Being and Doing into Curricula with a Digital Learning Space by Amanda K. Edgar, Lea Piskiewicz, Sureikha Ratnatunga, Anthony Neylan, Ruary Ross, Shannon Kilmartin-Lynch, Paris Beasy and Angela Ziebell is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

If you plan on adapting this chapter, please use the following attribution statement:

*Title of your adaptation* is adapted from Envirocare: A Collaborative Approach to Integrating Indigenous ways of Knowing, Being and Doing into Curricula with a Digital Learning Space by Amanda K. Edgar, Lea Piskiewicz, Sureikha Ratnatunga, Anthony Neylan, Ruary Ross, Shannon Kilmartin-Lynch, Paris Beasy and Angela Ziebell is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

About the authors

Amanda Edgar is a Senior Lecturer at Deakin University, where she provides leadership on the strategic vision and execution of projects that improve learning environments for both students and staff. She has significant experience from past positions, where her innovative teaching methods and leadership have earned recognition through esteemed awards such as Deakin’s Vice Chancellor Awards and an AAUT Teaching Excellence Citation. Her research focuses on promoting inclusion, diversity, and innovation in higher education through digital and physical learning spaces, with the goal of enhancing student success. Amanda identifies as an ally to First Nations Australians and is a third generation Australian living on Wadawurrung country.

name: Lea Piskiewicz

institution: Deakin University

After graduating with her master’s degree in France, Lea moved to Australia to establish herself as a user experience designer and apply her skills and experience to the education industry. Since joining Deakin, she worked across different teams, collaborating with learning designers and academics to support the visual needs for T&L content.

She had the beautiful opportunity to work and collaborate on numerous Indigenous Knowledge and inclusive resources throughout the years. She has developed her design process around care, empathy, and close collaboration, ensuring a uniquely rich and meaningful aesthetic that supports a positive learning experience for students and staff.

name: Sureikha Ratnatunga

institution: Deakin University

Sureikha Ratnatunga is Information Technology professional working in Deakin Learning Futures (DLF), Digital Learning Team as a Business Analyst/Architect. She has significant experience in implementation of IT projects and process improvement to provide business efficiencies. Sureikha is a recipient of Deakin’s Vice Chancellor Awards for such project implemented at Deakin. Sureikha identifies as an ally to First Nations Australians and is a first generation Australian.

name: Anthony Neylan

institution: Deakin University

Tony has worked at Deakin University as Multimedia Designer for the past 20 years specialising in Web and Visual Design. His lifelong passion for art and his professional experience in various mediums has opened doors to many creative endeavours in both Australia and abroad.

name: Ruary Ross

institution: Deakin University

Ruary Ross is a technology management professional working in Deakin’s Digital Learning Futures (DLF) Team to manage the Digital Learning Environments. He has significant experience in Program and Project Management disciplines as well as Operational Management, recognised by Deakin’s Vice Chancellor Awards. Ruary identifies as an ally to First Nations Australians and is a first generation Australian.

name: Dr Shannon Kilmartin-Lynch

institution: Monash University

Dr. Shannon Kilmartin-Lynch is a proud Yowong-Illam-Baluk and Natarrak-Baluk man, belonging to the Taungurung people of Victoria’s North-East Kulin Nations. Grounded in his cultural heritage, Dr. Kilmartin-Lynch’s research embodies a profound commitment to caring for Country and mitigating the environmental impact of waste materials. With an eco-centric perspective guiding his work, he consistently upholds these values, leading to significant global impacts.

Paris Beasy is a proud Torres Strait Islander woman who is passionate about integrating Indigenous knowledge with STEM. Holding a Bachelor of Science from Monash University, she focuses on developing decolonised research methods and Indigenous science curriculums that honor traditional knowledge. As a Marketing and Communications Officer for the Office of the Pro Vice-Chancellor (Research) at Monash, Paris leverages her skills in communication, photography, and design to translate complex research for broader audiences, advocating for inclusivity and cultural awareness in STEM while bridging Indigenous and Western knowledge systems.

name: Dr Angela Ziebell

institution: Deakin University

Angela is a Chemist who used to work with biomass and nature products. More recently Angela has moved into curriculum development/teaching with her research focus now STEM education to prepare our students for their future workplaces/lives. Cultural intelligence is a large part of workplace preparation. Angela started privileging First Nations voices and science in 2018 and Envirocare is the latest project to bring engaging educational opportunities to STEM students to help them learn about First Nations science. This includes helping students understand the lasting damage that colonisation has done to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and the environment.