Advocacy

Aligning Open Education Programs with Academic Reward and Recognition

La Trobe University

Hugh Rundle and Steven Chang

Overview

Open Education Practice (OEP) programs often wrestle with a key dilemma: how do we attract academic project participation in an institutional environment that doesn’t reward open educational practices (OEP)? Standard academic reward and recognition is tied closely to research publication outputs. By contrast, publishing teaching texts is unrewarded at best and often actively discouraged.

For teaching staff, investing time into open education initiatives will only become a priority if these projects will:

- advance a greater purpose beyond the open educational resource (OER) itself

- actively solve existing problems in learning & teaching practices

- align with academic reward and recognition program criteria.

This case study explores how the La Trobe eBureau, an open education program, tackled this problem. It focuses on how librarians used reflexive and reflective thinking to draw upon the experiences of academic open practitioners and develop solutions to this dilemma.

We suggest that the most effective way to align OEP with institutional incentives is to target award, grant, and promotion programs that are learning and teaching focused (rather than research publication focused). Our experiences highlight that the key avenues for achieving this are empowering teaching staff as open practitioners and equipping them to engage in OER-enabled scholarship of learning and teaching.

Using this case study

- Open Education teams will: Learn strategies for developing impactful open education projects and incentivising academic authors.

- Educators will: Understand the benefits to their teaching and opportunities for academic reward available by engaging with open education on its own terms.

What we were trying to solve

- Resistance or hostility from senior academics to support teaching staff time for writing OERs due to the perceived negative impact on academic progression: time writing an OER is time not writing research articles

- Struggles experienced by authors to get their OERs classified as research outputs to get recognition for the work and “justify” the workload

- The need to improve how we promote our OERs both internally and externally.

What we initially tried

- Seeking grants and funding to pay out teaching time for academics to spend the time writing their OER textbook – looking for external grants and talking to the Advancement team

- Advocating to senior academics on the merits of open textbooks from a student equity perspective

- Developing promotion and communications campaigns and holding online book launches.

Doing OER advocacy ‘smarter, not harder’

The La Trobe eBureau was founded in 2016 and has spent almost a decade engaging in serious OER advocacy, which has brought both immense successes and many failures. Recently, we shifted gears to a strategy focused on advocating for OER in a ‘smarter, not harder’ way. A key part of this change was adopting a slower, analytical, debrief-based approach powered by reflective practices. This aimed to unearth the underlying drivers for both our unexpected successes and our recurring stumbling blocks.

Formalising reflection and reflexion

In 2024, we began normalising a new practice of holding formal “retrospectives” with everyone involved in a particular open education project (both academics and professionals), scheduled just prior to the point of publication. This structured practice serves as a project debrief and provides valuable insights into what worked and did not work for each project. Crucially, it also encourages reflexive practices, which is an approach that goes deeper than reflective practice. Its distinguishing feature is that it focuses on how participants see themselves and their ‘given’ assumptions. This can cultivate thinking about how they have changed as practitioners.

This generates questions like:

- ‘how does my positioning affect my assumptions about Stakeholder A?’

- ‘how do my initial assumptions about the benefits of OER affect how I collaborate with Community A to achieve project goals X and Y?’

These insights have generated a profound rethinking process about fundamentals, which has compelled us to revisit the purpose of open education and how we reframe it to ourselves, our colleagues, and the university community. These changes have been so powerful that we have now embedded reflective practice across our whole open education program.

Reflexive practice question: how do our unexamined assumptions compromise our advocacy?

We use the term ‘reflexive practice’ here to highlight how we critically examined our own position as librarians with no lived experience being an academic. Recognising this helped us to ‘unlearn’ our assumptions about how academic workloads operate. This made us more attentive to how teaching staff experience OER barriers.

Critically understanding our own positioning helped us position our OER advocacy differently. We used this ‘smarter, not harder’ approach to recognise we were on the wrong path when we asked academics to estimate how much money would pay out teaching hours to free up time for developing open textbooks.

Feedback from teaching staff identified the following problems with this idea:

- Estimating this figure was difficult because the question “how much time do you need to write a textbook” is impossible to answer without any specific context

- Paying out teaching time withdraws teaching staff from active teaching practice which severs the “live” link between OER development and reflective practice

- Single-minded focus on a sole specific long-term task (like developing an OER) will be crowded out by competing priorities unless it is nested as a means to achieve a higher priority purpose

- Finding colleagues who can replace teaching staff is difficult. This takes a significant amount of time, handover work, and administrative planning.

In a nutshell, we identified that we were framing OER development as a separate activity to be added to and subtracted from academic workloads. This approach creates a major problem because it frames OER initiatives to teaching staff as standalone units of ‘more work’. This additive approach also separates it from teaching activities, rather than seeding projects from existing teaching practice to solve problems from within (by doing them differently). This ‘more work’ narrative means that teaching staff often (understandably) dismiss these ideas as “nice to have, but yet another thing I can’t fit into my unsustainable workload”.

Reflective practice question: what is the point of open education?

Our reflections about why our approach was failing led us to a broader examination of how we see open education and frame its purpose.

When we first launched the La Trobe eBureau, we primarily envisaged it as a social justice intervention to save textbook costs for students (Salisbury et al, 2023). This rationale was understandable at the time: it was driven partly by our institution’s values and student demographics, and partly because as an emerging program we took a lead from experienced U.S. initiatives.

However, our experiences highlight that framing student cost savings as the primary benefit of OERs has three weaknesses, particularly in Australia:

- Zero Textbook Cost programs for saving student costs aren’t directly rewarded (in their own right) in the current Australian higher education system (unlike in the U.S.)

- Framing OER as “just like commercial textbooks, but free” is enormously self-limiting, as it doesn’t recognise the full spectrum of OER capabilities for transforming teaching. For example, many La Trobe academics express frustration about the ‘one size fits all’ nature of traditional textbooks: that they are static, dry, and content-focused rather than pedagogically-focused. By contrast, OER projects can enable much more ambitious goals such as ‘fit-for-purpose’ alignment of form, content, and pedagogy. This is because they are uniquely flexible and not required to ‘be everything for everyone’ for mass market profits.

- Single-minded focus on student cost savings does not always speak to the diverse priorities of teaching staff. Putting all our eggs in this basket meant we missed the big picture: ‘OER-enabled pedagogy’. This is a radically open-ended toolbox for solving a wide spectrum of problems (Wiley, 2021). Its broad utility to all open practitioners is enabled by the defining feature of OERs: the ‘five Rs’. Many academics do care deeply about student equity but are rarely incentivised to tackle this problem, so in a time-poor environment, it is often drowned out by competing priorities. A narrow advocacy strategy focused solely on one benefit will fail to engage these other urgent priorities.

Centring the practitioner on their own terms

Bringing these three points together, we decided to broaden our view of open education beyond student cost saving benefits. We were influenced by researchers who have highlighted that teaching practitioners’ agency is decisive for widening OEP engagement (Stagg, 2023). This research suggests that practitioners are influenced by a wide ‘ecology’ of context-sensitive factors, and therefore advocacy needs to be flexible rather than singular or static.

Combining our experiences with this research, it became clear that we needed to diversify our advocacy. This pivot aimed to recognise the wide-ranging priorities of teaching staff on their own terms and actively align OEP with them. Taking this as our new starting point, we became much more effective at articulating open education as an extension of practitioners’ existing work to address goals that are meaningful to them, rather than ‘more work’ that adds new goals. This does not mean advocates should deprioritise student cost saving benefits, but it does mean situating these benefits as one element in a richer multi-pronged advocacy strategy, thereby avoiding a single point of failure.

Rethinking our fundamental vision

Fitting a square peg into a round hole

For years we wrestled with a key dilemma: how do we incentivise open textbook projects, given that OERs are excluded from the criteria for classification as research publication outputs? It makes sense that research outputs are a priority for many academics, given that it has implications for academic workload allocation. However, after investing immense efforts into diverse strategies to solve this problem, we found very little success except one sole win for the humanities open textbook Democracy in Difference. This was discouraging, but our initial disappointment enabled us to take an important step back so we could reflect and reframe our approach.

Transitioning from OER to OEP

Our pivot to searching for alternative solutions turned out to be decisive. Reflexive practices helped us to step back from the ‘librarian perspective’ and examine the big picture. We then used our new broadening understanding of open education to find better ways of supporting teaching practitioners. This meant redeveloping the La Trobe eBureau’s fundamental vision.

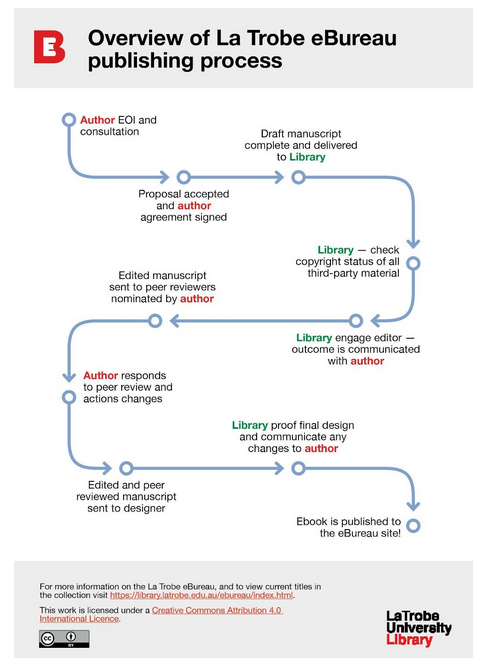

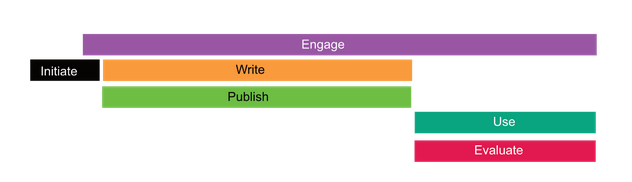

Our first step was to abandon our traditional Library-centric ‘production pipeline’ mindset in which we positioned ourselves primarily as OER publishing experts. In this schema, publishing OERs was the project endpoint in itself, rather than one key project milestone towards achieving broader transformation to achieve open practitioners’ goals. This was clearly reflected in our OER development workflow at the time, which represents a single-minded focus on OER production (see Figure 1).

This approach suffers from a fatal gap: it is not primarily framed by actual teaching staff practices and experiences. This is a key omission because these are the guiding stars for the most important pair of elements in any OER project: problem-focused ideation and post-publication implementation into learning design. These elements should drive OER production, not the other way around.

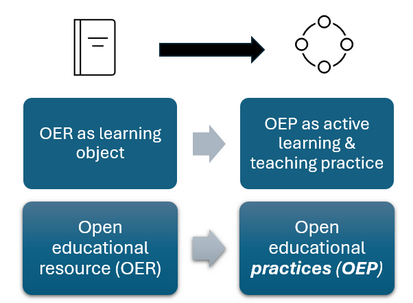

Our reflexive practices created the space for us to embrace sustained uncertainty about our new model. ‘Wiping the slate clean’ enabled us to transition towards a broader OEP-oriented framework (see Figure 2). This situates OERs in context: as a tool that must be paired with symbiotic learning & teaching practices to be impactful. Together, this pairing equips open practitioners to solve diverse problems.

Shifting focus to learning & teaching recognition

We turned our attention towards learning & teaching reward programs (e.g. teaching awards, grants, and promotions) once we recognised that it was a dead end to get OERs counted as research publications. Naturally, the criteria for these programs are much more strongly aligned with open education projects compared to research publications criteria.

However, this alignment is not plainly self-evident. These incentive programs do not mention OERs and therefore open education programs can play an invaluable role by connecting the dots to support practitioners (see Table 1). We have been successful in articulating these connections to achieve recognition, but this was only possible because of our new approach to open education.

| Academic reward/recognition criteria | Alignment with OEP |

| Innovation in learning & teaching | OER-enabled freedom to design new learning models |

| Broad recognition in the scholarly community | Open access = high visibility |

| Influencing other educators | Building communities of practice around an OER |

| Disseminating knowledge widely | Open licenses maximise dissemination |

| Evidence to support your application | Tangible portfolio of OER + related analytics/data |

| Scholarship of learning & teaching | Research projects to evaluate OEP interventions |

OER projects as evidence for teaching recognition

Academics seeking recognition face a key challenge: the bulk of their teaching labour is ephemeral and therefore often rendered invisible and difficult to evidence. OER are uniquely placed as a tangible form to embody these practice-based efforts. OER analytics are powerful for this, as quantitative indicators are easily understood by university administrators.

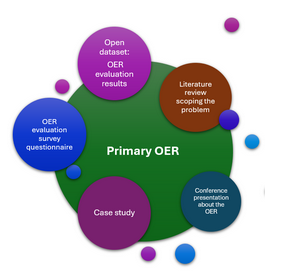

We have found this to be a transformative discovery for using ‘primary OER’ (such as open textbooks) to support award, grant, and promotion applications. So we are now piloting this strategy across the whole learning & teaching cycle (See Figure 3). We use our open repository to publish ‘secondary OER’ as open artefacts (e.g. assessment rubrics and OEP project tools / surveys). Consciously or otherwise, this exemplifies the knowledge production aspects of Hamilton and Hansen’s ‘practice-led research’ OEP model (2024).

Problem-focused OER design for impact

From our experience, there is one common factor that generates both academic motivation for open education projects and success in reward & recognition: a systematic understanding of the problem being solved. Less successful projects all suffered from vagueness in this area.

We illustrate this by examining two of our OEP projects that are successful in this way.

Example 1 – Threshold Concepts in Biochemistry

In the case of Threshold Concepts in Biochemistry, the project was driven by enthusiastic academic motivation for OER development. This energy was generated by strong clarity about the project’s greater purpose for solving specific teaching problems (it’s ‘why’). A key ingredient was investing in patient ideation for understanding the problem on a deeper level, enhanced by a collaborative ‘critical friend’ model.

Our methods included:

- classroom observations and reflective teaching practices

- analysis to identify common student errors

- a targeted literature review of biochemistry education studies

- breaking down the problem into distinct elements

- scoping out the breadth of the problem

These efforts directly generated a clear series of guiding principles for how we would achieve problem-focused OER impact (see Table 2). In turn, these naturally led to formulating well-defined project aims and scope: to develop a concise and conceptually-focused resource that specifically tackles STEM threshold concepts in an accessible way.

| Problems identified | Guiding principles for OER-enabled solution |

| Struggles learning complex “threshold concepts” | Break down threshold concepts into elements |

| Anxiety and under-confidence | Express a pastoral educator presence/voice |

| Didactic teaching models | Use a conversational tone |

| Intimidating content-heavy traditional textbooks | Tightly focused scope, exclude unnecessary detail |

| Difficulty navigating detail-level information | Provide conceptual framing to navigate details |

| Discipline-wide and global learning problem | Choose permissive open license to enable reuse |

The harmonious relationship between this project’s purpose, principles, and outcomes resulted in strong OEP alignment with all the reward criteria discussed earlier in Table 1.

This led to several career recognition achievements for the lead author (Julian Pakay) such as:

- Successful CAUL grant application

- Being commissioned by two biochemistry journals to write articles on OER

- Attracting two cross-institutional co-authors

- 12,500 web engagements; 5,633 visitors; 2,480 downloads

- International recognition through three glowing reviews on Open Textbook Library

Julian also won a Scientific Education Award in Australian biochemistry by applying similar problem-focused OER design methods for an earlier project, Foundations of Biomedical Science: Quantitative Literacy Theory and Problems.

Example 2 – Becoming a Climate Conscious Lawyer

In this example, we demonstrate how OER projects can scale up impact by seeding themselves inside larger practice-based interventions to enhance existing project goals. In this case, the educational intervention is not merely a “new open textbook”, but rather a sweeping project called Climate Conscious Lawyers led by legal educators and practitioners. It aims to fundamentally change the nature of Australian legal education by mainstreaming climate change considerations into it.

Our open textbook Becoming a Climate Conscious Lawyer forms a key part of this, but was itself generated by the preceding foundational project phase to systematically understand the problem through a national survey of law academics. This created strong clarity of purpose for the second phase to develop Becoming a Climate Conscious Lawyer as the ‘core content’ OER responding to the climate change teaching gaps expressed by the survey respondents.

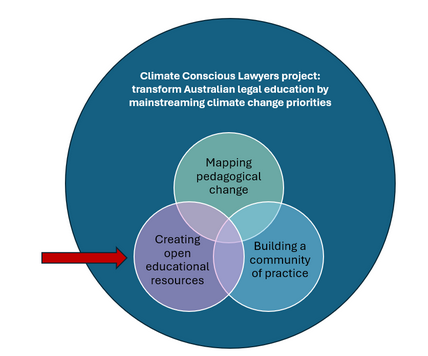

This OER is powered by an unusually large group of practitioners (many recruited as authors from the survey contact list) because the project’s problem-focused clarity resonates with their collective values and teaching experiences. This group has formed an emerging community of practice generated by their passion for solving this problem (see Figure 4).

Climate Conscious Lawyers is a project that uses OER as one of its three primary tools (see Figure 5). It is an expansive OEP-powered project to solve problems in legal education at scale, rather than a standalone OER production project. This is a more holistic approach where OER production serves a greater purpose than itself.

Impact evaluation follows from problem focus

Establishing a clear problem to be solved made it easier to assess OEP project impact. Evaluation methods follow directly from the problem-focused OER ideation phase. Like any other teaching intervention, it boils down to these questions:

- Based on our goals established to solve the problem, how do we know if the intervention worked?

- Did it work?

At this point, things came full circle to solve an unexpected earlier dilemma. We observed that our most engaged practitioners shared a common general process:

- Identify a phenomenon within teaching and learning

- Develop a hypothesis about the phenomenon

- Run a controlled teaching intervention to test the hypothesis

- Evaluate the intervention’s impact in these terms

Sure looks like a scientific experiment to us!

This simple formula generates a multitude of open publications and artefacts that directly address common institutional priorities around supporting the scholarship of learning and teaching (e.g. research-in-practice conference talks, journal papers on the teaching intervention, datasets, and other outputs). This process began as an OER evaluation method, but accidentally created a solution for our original problem: aligning OEP with reward and recognition incentives.

The process is the point: transforming practice

Our reflective practice through our ‘retrospective’ workshops has organically grounded our open education program in a concept we keep returning to: ‘process as pedagogy’. For us, this refers to how OEP acts as a learning experience in itself that transforms practitioners and changes how they relate to their teaching practices and students.

Influenced by our exposure to Indigenous Australian thinkers and worldviews (Yunkaporta, 2019), we started to question our traditional focus on the outputs, and examine the richness of the creative process itself (see Table 3). Most of the academics we collaborate with are transformed by the process of creating open textbooks and other OERs. What if the process is the point?

| Resource-centric model | Practice-centric model |

| Identify topic | Identify problem and possible solution |

| Write content | Find collaborators

Form community of practice |

| Publish content | Publish content |

| Measure usage | Evaluate impact of solution |

| Discuss and publish about intervention and impact | |

| Adjust teaching in response to findings |

We observed that the OER development process is enriched by progressively circulating new iterations of content to find collaborators, attract feedback, and form a community of practice that orbits the project. This insight drove us to revise our traditional approach to ‘book promotion’ that was originally a discrete post-publication launch phase. We replaced this with a cycle of continuous engagement that begins disseminating an initiative as soon as a project proposal is formalised.

Here is a sketch of this new process to help prospective open practitioners understand where everything fits in (see Figure 6):

But what happens after evaluation? If the evaluation finds that the resource needs to be amended or added to, someone from the community we have created might want to amend it. The process is, in fact, a never-ending cycle (see Figure 7):

What we learned

Bringing together all these elements, we believe we have resolved a number of challenges:

- Time management: The best way to tackle time management challenges is to reframe the problem by focusing on practitioners’ existing priorities and motivations. Open education projects are uniquely capable of aligning with both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. However, this requires situating OER development as a means to achieving greater ends that are meaningful to practitioners for solving an existing identified problem, rather than being an end in itself isolated from bigger priorities.

- Motivation: Most educators are intrinsically motivated to improve their experience of learning and teaching, both for themselves and their students. Empowering these practices is more effective than focusing on a ‘publishing output’, especially when advocates connect the dots between OEP and learning and teaching reward criteria. If the purpose is clearly aligned with evaluation planning, this naturally generates scholarship of learning and teaching outputs, which comes full circle to feed extrinsic motivation by publishing research.

- Impact: When practitioners frame their OER planning in a problem-focused way, evaluating the impact of the resource will follow naturally from this. Sharing evidence of impact will also drive adoption by other practitioners.

- Engagement: The OER development process generates more than the primary OER output it publishes. The concept of ‘process as output’ can continuously engage other educators and build an emerging community of practice. This group can collectively contribute and serve as enthusiastic early adopters rather than a new audience to whom we have to ‘cold sell’ the resource.

- Reward and recognition: OERs align poorly with criteria for research publication classification. By contrast, they are a natural fit with learning and teaching focused academic reward systems (when paired with synergistic teaching practices). Problem-focused OER design is more likely to create impact and enable evaluation, which in turn positions practitioners to fulfil recognition criteria related to evidencing scholarship of learning and teaching.

We started by thinking about how to attract authors and ended up in an unexpected place! The answer was essentially to turn our assumptions on their head: Academic reward and recognition follows on from addressing clear educational goals, engaging with educators in the field, and measuring the impact of the project.

In practice

Our paradigm shift in thinking means we are now focused on overhauling our existing program and processes to ensure that we:

- Connect with the diverse existing priorities of academics by demonstrating how OEP can address these. Achieve this by promoting a multi-pronged spectrum of open education benefits and avoiding narrow advocacy strategies.

- Prioritise support for teaching-focused staff to develop themselves as holistic open practitioners. Systematically integrate reflexive practices into OER development (rather than a single-minded focus on quantitative OER production).

- Identify specific teaching problems and formulate measurable goals that will solve these problems. Use this to generate meaningful motivation and guiding principles to drive projects.

- Connect the dots to align OEP programs with criteria for learning and teaching grants, awards, and promotions, rather than research publication classification criteria.

Inspired by Anna Rubinowski and Lauren Halcomb-Smith’s workshop on rubrics at the 2024 VALA conference, we are developing a rubric to guide how we critically assess new open education project proposals. In the spirit of OEP, we are sharing our current iteration – we encourage you to provide feedback or adapt it.

References

Hamilton, D., & Hansen, L. (2024). An artful becoming: The case for a practice-led research approach to open educational practice research. Teaching in Higher Education, 0(0), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2024.2336159

Rubinowski, A & Halcomb-Smith, L. (2024). Creating narrative-based rubrics for library services evaluation. VALA 2024. https://www.vala.org.au/vala2024-proceedings/vala2024-workshop-3-rubinowski

Salisbury, F., Julien, B., Loch, B., Chang, S., & Lexis, L. (2023). From knowledge curator to knowledge creator: Academic libraries and open access textbook publishing. Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication, 11(1).

Stagg, A. (2024). The Ecology of Open Educational Practices in Australian higher education: a practitioner-focused mixed methods study (Doctoral dissertation, University of Tasmania).

Wiley, D. (2021). OER-Enabled Pedagogy, in An Introduction to Open Education. https://edtechbooks.org/open_education/oer_enabled_pedagogy

Yunkaporta, T. (2019). Sand Talk: How Indigenous thinking can save the world. Text Publishing.

Image descriptions

Figure 1: a Library-centric ‘production pipeline’ schema that informed the La Trobe eBureau’s traditional practices

A diagram illustrating the original La Trobe eBureau OER development process. A flowing arrow begins at the starting stage “Author EOI and consultation” and ends at the last stage “Ebook is published to the eBureau site!”. Several stages are marked throughout this process: in order they include draft manuscript submission, copyright review, copyediting, and peer review.

Figure 2: transitioning away from a publication-focused OER-centric approach to an active OEP practice-based framework

A box showing movement from concepts on the left to those on the right. A header row shows a book with an arrow pointing right to an icon representing a circular process diagram.

Underneath the header row are two more rows. In the first is a box labelled “OER as learning object”, with an arrow pointing to “OEP as active learning & teaching practice”. The second row shows “Open educational resource (OER), with an arrow pointing to “Open educational practices (OEP) – the last two words are emphasised.

Figure 3: open artefacts generated through OEP that “orbit” a primary OER, and can be considered secondary OER recognised as both research and learning & teaching outputs

A cluster of circles indicate a “constellation” of concepts that work together. In the centre, a large green circle is labelled “Primary OER”. Around the edges of this circle are five smaller circles in various colours. They are labelled, from top-left moving clockwise:

- Open dataset: OER evaluation results

- Literature review scoping the problem

- Conference presentation about the OER

- Case Study

- OER evaluation survey questionnaire

Several other even smaller circles also surround this group – they are not labelled, representing possible (theoretical) other aspects of the project.

Figure 4: collective passion for solving a problem brings together a community of practice

A large pink circle labelled “Community of practice” is surrounded by other smaller light pink circles, several of which are labelled. These labels are, from top-right clockwise:

- Peer reviewers

- Authors

- Champions

- Editors

- OER experts

Several smaller, unnamed circles also make up the image.

Figure 5: creating OERs is one of several elements enabling a higher-level project goal

A large blue circle is labelled “Climate Conscious Lawyers project: transform Australian legal education by mainstreaming climate change priorities”. In the lower half of the circle site three smaller circles which intersect symmetrically, in a venn diagram. A red arrow points to these smaller circles from the left.

The smaller circles are labelled, from the left clockwise:

- Creating open educational resources

- Mapping pedagogical change

- Building a community of practice

Figure 6: Different elements of an OE project overlap rather than being entirely sequential. Engagement continues through most of the life of the project

Coloured bars indicate a gantt chart. The top row is purple and labelled “Engage”. This runs almost the entire length of the page. The next row has two bars – on the far left is a black box labelled “Initiate”. The prior row (Engage) begins just before the “Initiate” box ends. It is followed on the same row by a yellow box labelled “Write”. Directly underneath, matching the length and start and end points of “Write” is a green box labelled “Publish”. These boxes run for approximately 60% of the length of the chart. On the next row is an aqua box labelled “Use”, and directly under that is a matching red box labelled “Evaluate”.

Figure 7: The project timeline becomes circular, with use and evaluation providing insights that fuel the next iteration

This diagram represents the same concept and workflow as the gantt chart in figure 6. It is, however, now bent back on itself to form a series of concentric circles rather than being straight lines.

Acknowledgement of peer reviewers

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following people who kindly lent their time and expertise to provide peer review of this chapter:

- Sarah McQuillen, Academic Librarian, University of South Australia

How to cite and attribute this chapter

How to cite this chapter (referencing)

Rundle, H., & Chang, S. (2024). Aligning Open Education Programs with Academic Reward and Recognition Incentives. In Open Education Down UndOER: Australasian Case Studies. Council of Australian University Librarians. https://oercollective.caul.edu.au/openedaustralasia/chapter/aligning-open-education-programs-with-academic-reward

How to attribute this chapter (reusing or adapting)

If you plan on reproducing (copying) this chapter without changes, please use the following attribution statement:

Aligning Open Education Programs with Academic Reward and Recognition Incentives by Hugh Rundle and Steven Chang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

If you plan on adapting this chapter, please use the following attribution statement:

*Title of your adaptation* is adapted from Aligning Open Education Programs with Academic Reward and Recognition Incentives by Hugh Rundle and Steven Chang, used under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

Teaching techniques and academic practices that draw on open technologies, pedagogical approaches and open educational resources (OER) to facilitate collaborative and flexible learning.

Open Educational Resources (OER) are learning, teaching and research materials in any format and medium that reside in the public domain or are under copyright that have been released under an open license, that permit no-cost access, re-use, re-purpose, adaptation and redistribution by others.

An open education program which works with teaching staff to develop themselves into open practitioners by using OER to engage in open educational practices. Based at La Trobe University and hosted by the Library.