2 Pacing to Enable Participation

Pacing to Enable Participation

Olivia Richards and Danielle Hitch

If this is your first visit to the textbook, please take a moment to read the About This Book chapter to get the most out of your experience.

You may find some material in multiple chapters (such as an introduction to common symptoms of Long COVID) because we anticipate some readers will only access certain chapters. Please feel free to skip any material you are already familiar with.

The goal of this chapter is to present evidence-based strategies that help individuals with Long COVID engage in daily activities while managing fatigue and/or pain. Pacing, which involves balancing activity with rest, is a key strategy for avoiding overexertion and effectively controlling symptoms. By grasping the principles of pacing and how to implement them, informed and shared decision-making can assist people with Long COVID in enhancing their health, wellbeing, and quality of life. This chapter is designed to empower both clinicians and people with Long COVID to better manage energy levels, decrease the frequency and severity of symptom flare-ups, and progressively improve or sustain their ability to participate in everyday life.

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter and completing the learning activities you will be able to:

- Understand the concept of pacing and its importance in managing fatigue in Long COVID

- Identify key strategies for effective pacing.

- Recognise the signs of over exertion.

- Plan and apply pacing techniques in daily activities to manage energy levels.

- Utilise tools and resources to support pacing strategies.

Introduction

The World Health Organisation (WHO) describes Long COVID as “the continuation or development of new symptoms three months after the initial SARS-CoV-2 infection, with these symptoms lasting for at least two months with no other explanation”[1]. More recently, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) have released an updated definition, describing Long COVID as “an infection-associated chronic condition (IACC), specifies a minimum duration of 3 months, and expressly incorporates common symptoms and diagnosable conditions characteristic of Long COVID”[2]. This definition provides symptom examples, recognises intermittent symptoms, and emphasises equity in care. It also recognises that exacerbation of existing symptoms can be a manifestation of Long COVID, in contrast to the WHO description which explicitly excludes symptoms which can be attributable to a pre-existing condition.

The impact of Long COVID on participation in daily life can be profound. People may struggle with basic tasks, experience difficulties in maintaining relationships, and face emotional challenges such as anxiety and depression provoked by their ongoing issues. Creating individually tailored strategies to manage symptoms and enhance overall well-being is crucial to enabling people with Long COVID to fully participate in their own lives and communities [3]. This chapter will provide readers with practical tips, tools, and resources to support both clinicians and people with Long COVID to successfully apply pacing techniques in everyday life.

Signs and Symptoms

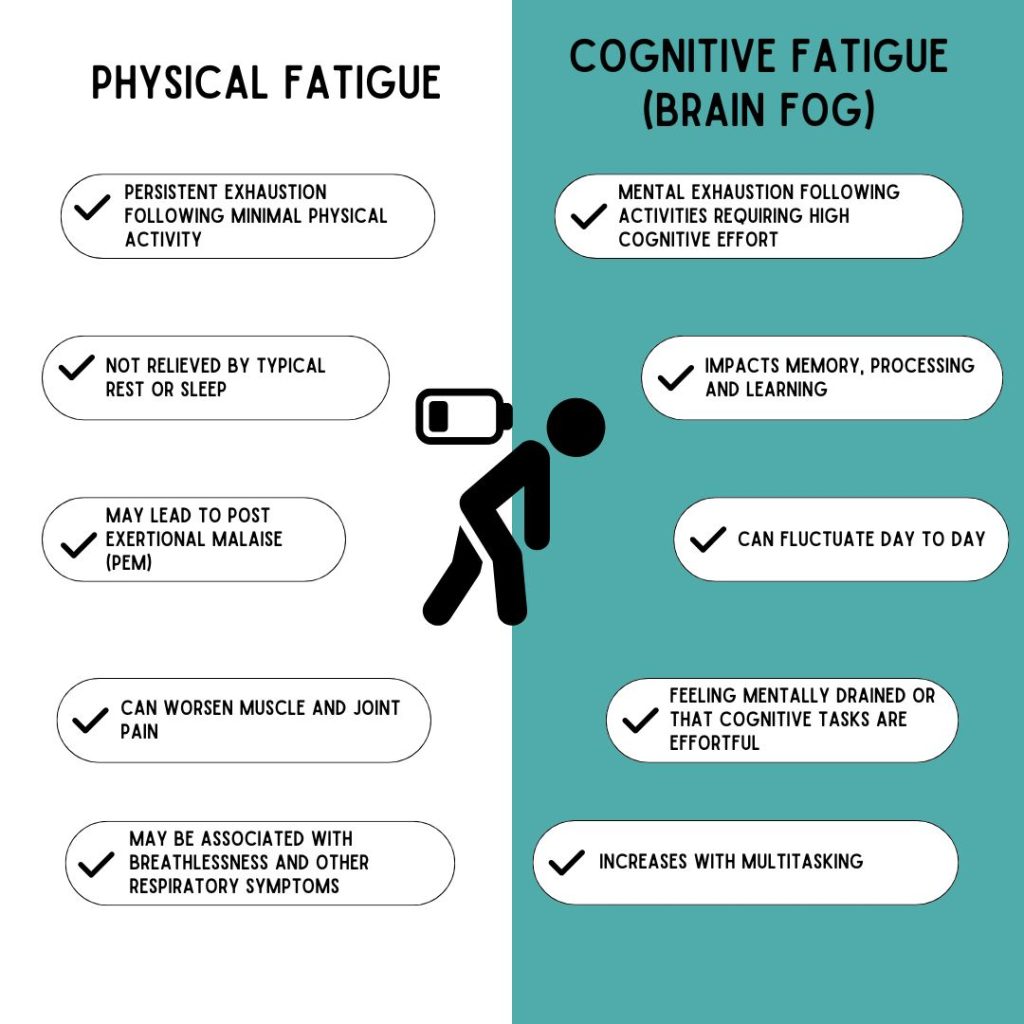

The symptoms of Long COVID differ significantly from one person to another, making accurate identification and management difficult [4]. Fatigue is one of the most common features of Long COVID and is categorised into two types: physical fatigue, which results from repeated muscle use, and cognitive fatigue, often referred to as "brain fog" [5].

"Something most people take for granted is being able to get out of bed and shower or wash daily. This is now a major task for my friend, and requires a lot of pacing and planning. Her bed is her best friend at present. Life is passing by on a daily basis, she can see life outside her window but cannot be part of it. Cognitive function has been taken from her and what she could do she cannot even think about now" [6].

Many people with Long COVID also experience sleep disturbances, due to a combination of symptoms [11]. These symptoms may include difficulties with falling asleep, staying asleep, or waking up too early. Poor sleep quality exacerbates fatigue, therefore strategies to optimise sleep should be considered to support people with Long COVID manage their feelings of fatigue. [12].

Before moving on, watch the following video summary (3 mins 50 sec) of how fatigue and PESE presents in people with Long COVID to consolidate your learning.

Recognising and Screening for Post Exertional Malaise (PEM)

Post Exaceration Malaise (PEM), also known as Post Exertional Symptom Exacerbation (PESE) refers to an exacerbation of symptoms following physical, cognitive, or emotional exertion that would have been previously manageable. This exacerbation can occur immediately or with a delayed onset, typically ranging from hours to days after the exertion. [13] [14]. Recognising and screening for Post-Exertional Malaise (PEM) is crucial for effective Long COVID management using pacing and improving the quality of life for those affected. Early identification and management of PEM prevent the worsening of symptoms and potential overall deterioration in health and wellbeing. Early screening can address these issues by enabling timely interventions tailored to individual needs. Traditional diagnostic criteria often fail to fully capture the extent or severity of PEM symptoms. Few tests are available specifically for assessing brain fog, and existing diagnostic tools often lack the sensitivity needed to accurately detect this complex symptom. Consequently, patients frequently experience delays in diagnosis and healthcare professionals often lack confidence in recognising and managing PEM.

Methods for Recognising and Screening for PEM

There are two primary approaches for recognising and screening for PEM, which includes understanding the patients' lived experience and utilising specific screening tools. Both approaches for recognising PEM should be employed to gain a comprehensive understanding of this symptoms. Remember: Low scores on the screening tools does not negate the presence or severity of PEM [15].

Patient's Lived Experience:

Self-Monitoring: People with Long COVID should be encouraged to monitor their symptoms and energy levels regularly and in a standardised way. This can be achieved by keeping detailed diaries, activity logs, or utilising wearable technology to track exertion and symptom patterns, such as a smart watch or applications like Visible.

Patient Reports: People with Long COVID are experts in their own experience of the syndrome. Their subjective reports provide valuable insights into the impact of PESE on their health and wellbeing and must be incorporated into shared decision making and goal setting with healthcare professionals.

Screening Tools:

DePaul Post-Exertional Malaise Questionnaire (DSQ-PEM): This tool was designed specifically to detect PESE and is available in original, brief and paediatric versions.

Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS): This 10-item scale evaluates general symptoms of chronic fatigue, however it is not specifically designed to detect PESE.

Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS): This tool quantifies the impact of fatigue on daily life, including its relationship to motivation, physical activity, work, family, and social life.

When you find the right balance between activity and rest, you can:

- Participate in more activities that are personally meaningful and important

- Break the cycle of 'boom and bust' (explained in this chapter)

- Have better control over your energy levels throughout the day

The hardest thing about pacing is changing existing (and often long practiced) behaviors to create new habits and routines, a process that is neither simple nor linear. Behavior change is challenging because you are asking people to break old habits while simultaneously developing new and unfamiliar actions. Change becomes even more difficult when everything is cognitively demanding, such as during periods of brain fog. These changes ofter take much longer than expected. For example, a change as simple as drinking an extra cup of water daily takes about two months to become a consistent habit. When helping people with Long COVID make behavior changes, setbacks may be mistakenly perceived as laziness or stubbornness. However, viewing setbacks as opportunities for mutual reflection and problem-solving will increase the likelihood of success. Understanding and accepting that setbacks are part of the behavior change process can help both clinicians and people experiencing Long COVID achieve their goals [16].

Reflect on a time in your own life when you tried to build a new habit. Did you succeed? How long did it take? What helped you succeed or stood in the way of success? Who did you turn to for help and support?

It is important and helpful to recognise that establishing new behaviours and habits requires repeating a chosen behavior in the same context until it becomes automatic and effortless by integrating it into the daily routine. When a behaviour becomes part of a routine, it requires less conscious effort and decision-making, decreasing its cognitive demand and increasing the likelihood of it being sustained over time. All of which enables people with Long COVID to maintain or gradually increase their participation in daily life [17].

Before moving on, watch the following video to consolidate your general knowledge about pacing as a strategy for people with Long COVID. This video is 8 minutes long, however the first 4 minutes 20 seconds contains the most essential information.

What is Pacing?

Pacing is a self-management strategy designed to prevent Post Exertional Malaise (PEM). Pacing involves performing less activity than your maximum energy level allows, breaking activities into shorter segments, and incorporating frequent rest periods. It provides a tailored approach to managing Long COVID symptoms, recognising that each person's journey to recovery is unique [18].

The primary goal of pacing is to manage energy levels, prevent overexertion, and minimise the risk of energy crashes. By prioritising tasks and incorporating regular breaks, people with Long COVID can more effectively conserve energy throughout the day, resulting in a balanced energy expenditure.

Pacing is a highly individualised process, with each person’s journey varying based on their unique circumstances, abilities, and goals. Some individuals may focus on maintaining their current energy levels rather than increasing their activity, while others might experience gradual improvements that enable them to slowly increase participation. Additionally, some individuals may go through periods of remission, allowing them to significantly enhance their activity levels. Therefore, effective pacing strategies must be customised to meet each person's specific needs, abilities, and goals to achieve the best possible outcomes.

Theories and Analogies About Pacing

Pacing as a strategy is founded on the concept of energy conservation, which provides a theoretical basis for managing many conditions which cause fatigue. Energy conservation refers to techniques and approaches for minimising energy expenditure during daily activities, with the goal of using this energy wisely to avoid exhaustion and to maintain a manageable level of activity without overexertion [19]. There are a range of strategies aimed at minimising energy expenditure during daily activities, including prioritising tasks tasks, modifying the environment and adjusting behaviour or personal prctices.

There are many theories and analogies to explain the rationale for pacing and how it works. People with Long COVID may already be familiar with one or more of them, and clinicians should aim to use theories that resonate with each individual. There is no single way to understand Long COVID, so choose a way of explaining your reasons for recommending pacing that enhances understanding without leading to information overload. Some of these theories include:

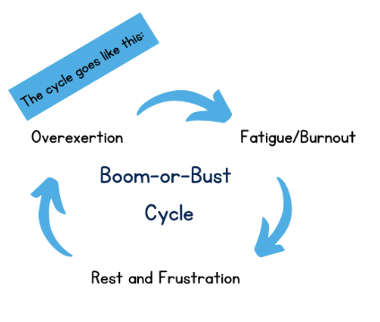

Boom/Bust Theory

The Boom-and-Bust theory describes a cycle in which individuals with chronic health conditions go through periods of high energy use, followed by fatigue or worsening symptoms. The "boom" phase involves increased activity or exertion, which is then followed by the "bust" phase, characterized by a significant drop in energy and functioning that can last for days [20]. On days when energy levels are higher, people often feel motivated to accomplish tasks and may try to make up for lost time [21]. This can lead to overexertion and ignoring the body's signals, resulting in a subsequent "crash." Continuously pushing beyond one's limits can cause more severe fatigue and longer recovery times, ultimately leading to a reduction in overall activity levels over time [22].

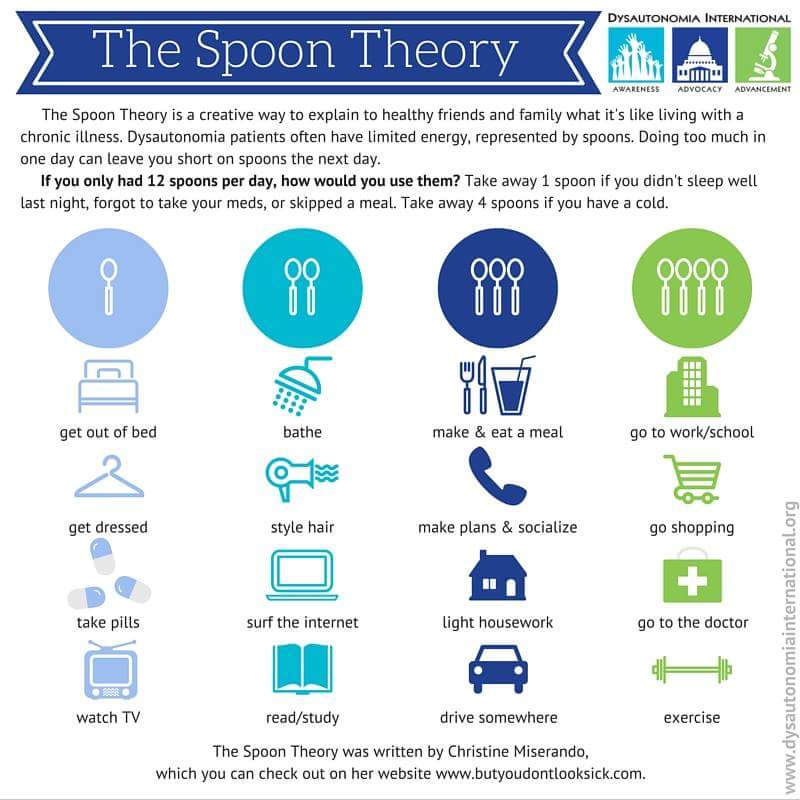

Spoon Theory

Spoon theory is a metaphor used to describe the limited energy available to individuals with chronic illnesses. In this metaphor, each "spoon" represents a unit of energy required for daily tasks, and people with chronic conditions must carefully allocate their spoons to manage their activities throughout the day [23]. Unlike those without such conditions, who may have what feels like an unlimited supply of energy, individuals with chronic illnesses start each day with a finite number of spoons. This theory helps explain the concept of pacing by highlighting the importance of conserving energy to avoid exhaustion. Everyone has a different number of spoons, and by using strategies like rest and self-care, individuals can potentially increase their supply of spoons over time [24].

Imagine you only had 12 'spoons' of energy to use throughout your day. How would you choose to use them?

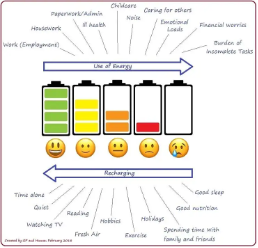

Battery Theory

The battery life metaphor is a helpful way to understand energy management for individuals with chronic conditions. Imagine your energy as a mobile phone battery. If you completely drain the battery, you'll have to wait for it to recharge before you can use the phone again. Similarly, if you exhaust your energy reserves, you'll need significant rest to recover. By using only part of the battery and recharging it regularly, your phone stays ready for use. This approach highlights the importance of balancing activity with rest. By managing energy through planned periods of activity and rest, individuals can maintain a more consistent energy level, allowing them to participate in desired activities more effectively. This metaphor illustrates the principles of pacing, demonstrating how careful energy management can improve daily functioning [25].

For the remainder of this chapter, we will be using the persona of Jennifer for learning activities. Please take the time to review Jennifer's story before continuing.

Jennifer's story contains descriptions that may be triggering or upsetting for some readers due to its detailed description of her lived experience of Long COVID. We acknowledge that this book addresses sensitive topics, and we encourage you to monitor and take care of your well-being while engaging with the material. You may choose to use another persona if you wish.

Pacing versus Graded Exercise Therapy (GET)

Paing and activity modification are often mistaken for Graded Exercise Therapy (GET) but they differ significantly in focus and application.

- GET aims to improve physical fitness through structured, incremental increases in exercise intensity, often following a set protocol rather than individual presentations. People may be encouraged to tolerate some symptom exacerbation in the interests of complying with the protocol. GET is contraindicated for people with PEM in several international guidelines [26][27][28]

- Pacing gradually increases engagement in daily life, tailored to each person’s capacity and symptoms, emphasising energy conservation and avoiding overexertion. Symptoms exacerbation is seen as a sign to stop or scale back activity in the short term.

3 P’s Principle

The 3 P's Principle for Pacing is a practical strategy designed for use in daily life, to help manage energy levels and avoid overexertion[29]. This strategy encompasses three key components: Pace, Plan, and Prioritise.

PACE

To pace, you need to think how you approach tasks, aiming to perform them more slowly or divide them into smaller segments with breaks. This ensures you have enough energy to complete activities without worsening fatigue. In contrast, pushing yourself to exhaustion means you'll need a longer recovery period [30].

The basis of successful pacing is a comprehensive understanding of the various demands each activity places on a person. These may include:

| Physical Demands | e.g. moving, standing, reaching |

| Mental Demands | e.g. concentrating, remembering, understanding information, speaking, reading, writing |

| Sensory Demands | e.g. noise, light, temperature. |

| Emotional Demands | e.g. excitement, stress, upset, fear, sadness |

| Environmental Demands | e.g. objects and places at home, work, school and in the community |

| Task Demands | e.g. time demands, opportunities to adjust the way the activity is completed |

General Strategies for Effective Pacing

- Break activities into smaller tasks and distribute them throughout the day.

- Adjust different aspects of an activity to lower energy demands.

- Incorporate rest periods into your activities to recharge.

- Sit to rest whenever you can.

- Plan and reschedule activities to less busy times of day.

- Seek help from others where possible.

- Postpone non-urgent tasks until a later day

Using Pacing

One of Jennifer's goals was to keep on top of her laundry more effectively. Her current approach is to complete the laundry all in one go in a 'big push'. She reports she needs to rest for 20 minutes after folding the clothes, and reported feeling achy and more fatigued the next day.

With the support of her clinician, she broke down this activity into more manageable steps:

- Sorting clothes: Jennifer sits down next to her laundry basket and sorts the washing loads in 5 minute blacks with breaks in between.

- Loading the washer: After resting, she loads the washer slowly, taking a seated rest break halfway through. Then breaks again after the washing is loaded, and the washing cycle has begun.

- Moving clothes: When the washing cycle ends, she transfers to clothes to the washing basket, taking a longer 15-minute break to recover, before hanging them on the clothing rack.

- Folding clothes: Finally, she folds the laundry taking short breaks after each small pile.

PLAN

As shown in the previous example, planning activities ahead of time provides the groundwork for pacing. By examine the activities the person typically engages in over the entire day or week, a plan can be created to distribute these activities more evenly. This plan will reflect each person's individual circumstances, taking into account personal interests, environment, and current level of functioning. A daily or weekly plan can include scheduled times for rest and recovery and arrange activities for times of day when the person feels more energetic [31]. Activities that already cause the person an increase in fatigue, breathlessness or pain are particularly good targets for breaking into smaller parts for completion over a longer period of time. An established plan also helps to reduce stress and cognitive load, and help to identify the current activity baseline [32].

Pacing plans should be reviewed every 1-3 months to ensure adjustment with the persons current condition and needs. This regular assessment helps to track progress, adjust to any changes in symptoms or energy levels, and incorporate new strategies as necessary. It also ensures that the plan continues to support the goals as they evolve.

General Strategies for Effective Planning

- Prepare in advance when possible.

- Establish consistent routines.

- Distribute activities over time.

- Organise the placing of necessary items so they are easily accessible.

- Seek out tools or equipment that can help minimise effort.

- Monitor and record your energy expenditure.

Other strategies

- Be gentle with yourself and avoid the pressure to accomplish everything.

- Strive for a balance between necessary and desired activities.

- If possible, delegate or eliminate tasks.

- Seek out activities that boost your energy levels.

- Instead of lifting items, try to push or slide them whenever you can.

- Remember to bend at your knees rather than your waist when picking things up.

Using Planning

With the support of her clinician, Jennifer drew up a weekly activity plan which included the following strategies for her laundry.

- Complete laundry during high energy window: Jennifer will complete her washing before lunchtime, when her energy levels are at their highest.

- Efficient setup: Jennifer has positioned washing baskets next to her washing machine and her shower to minimise walking to and from the bedroom with the laundry basket. She has also placed her clothing rack near the washing machine to reduce unnecessary movement.

- Rest Period: Jennifer has scheduled brief rest periods after each small step, and a larger one after starting the machine, and finishing her washing.

Prioritise

Prioritising helps individuals decide which activities must be completed at a specific time, and which can be delayed or deemed unnecessary. While some daily tasks are essential, others may not be as critical which provides opportunities for the establishment of new habits [33]. This process involves identifying the personal importance of activities, which reflects individual priorities and circumstances - what might be important for one person is not important to another. This approach allows for a more balanced daily routine, reducing stress related to incomplete tasks while ensuring the person can complete as many of their responsibilities as possible [34].

General Strategies for Effective Planning

Consider the following questions to determine which tasks are essential and non-essential.

- What are my must-do activities for today?

- What activities would I like to engage in today?

- Which tasks can be postponed for another day?

- Are there any tasks I can ask someone else to complete for me?

Using Prioritisation

With the support of her clinician, Jennifer identified which activities were most important to her and modified these activities to enable her participation.

- Complete essential washing only: Jennifer will wash only the clothes she needs for the next 2-3 days, ensuring each load is light.

- Delegate Task: Jennifer will ask her partner for assistance to retrieve the wet, heavy clothes out of the washing machine, reducing physical strain.

- Folding clothes: Jennifer will choose which items need to be folded and which could be placed directly in her cupboard.

- Balance domestic and leisure activities: After completing the essential laundry tasks, Jennifer will read her book, a low-energy activity she enjoys, to balance her day.

Activity (5 minutes)

Having read the examples above, answer the following questions:

- What else could Jennifer do to pace her laundry activities?

- What else could Jennifer do to further plan her laundry activities?

- What else could Jennifer do to prioritise aspects of her laundry activities?

Using the 3P's strategy on other daily activities

The 3P's strategy can be used for any and all activities in daily life. See below for a range of strategies and approaches you can use for specific activities when working with a person with Long COVID.

Grading or modifying activities

Balancing activity and rest is essential for managing fatigue and reaching daily functional goals. The initial focus should be on achieving a balance where tasks can be completed without causing fatigue. Once this balance is maintained and symptoms remain stable—typically for about a month—it suggests that the current pacing strategies are working effectively. When the person is ready to increase their activity levels, clinicians should work closely with them to determine the right timing and method for gradual progression. The goal is to safely and steadily enhance daily activity while closely monitoring fatigue levels and overall function. Generally speaking, this process starts with a specific time or task limit and gradually builds from there [35].

Ongoing symptom monitoring is vital for tracking progress and identifying any flare-ups or relapses. Progress varies among individuals but often people make quicker advances with activities which are aligned with their interests or needs. For example, a person with Long COVID might prioritise participation in activities like self-care while also prioritising their engagement with leisure pursuits such as knitting. However, they may also choose to maintain their current level of activity in tasks like meal preparation if this is less of a priority for them [36]. Starting the process of improvement with just one or two key areas at a time provides a greater sense of control and decreases the risk of flare-ups causing pain and discomfort. Gradually increasing activity, with careful monitoring, can eventually lead to higher overall activity levels and improved function but the maintenance of current levels of participation may also be a meaningful goal in the context of a person's overall health and wellbeing.

It's important to recognise that progress can vary among individuals. Some individuals may advance in certain areas based on their interests or needs. For instance, they might make progress in essential activities like self-care, while also enhancing leisure activities such as knitting. However, they might choose to maintain their current level of activity for tasks like meal preparation, particularly if they find cooking less enjoyable. It’s crucial to tailor the approach to each individual's specific needs and goals, focusing on what is most relevant and motivating for them [37].

Many people will compare their current abilities to what they could do prior to contracting Long COVID. This comparison may create additional pressure and frustration, as progress maybe slower than expected. Expectations can be managed by recognising and acknowledging that their current capacity differs from what they use to do, and setting realistic, individualised goals. Reducing self-imposed pressure to 'get better' helps support more sustainable and effective pacing

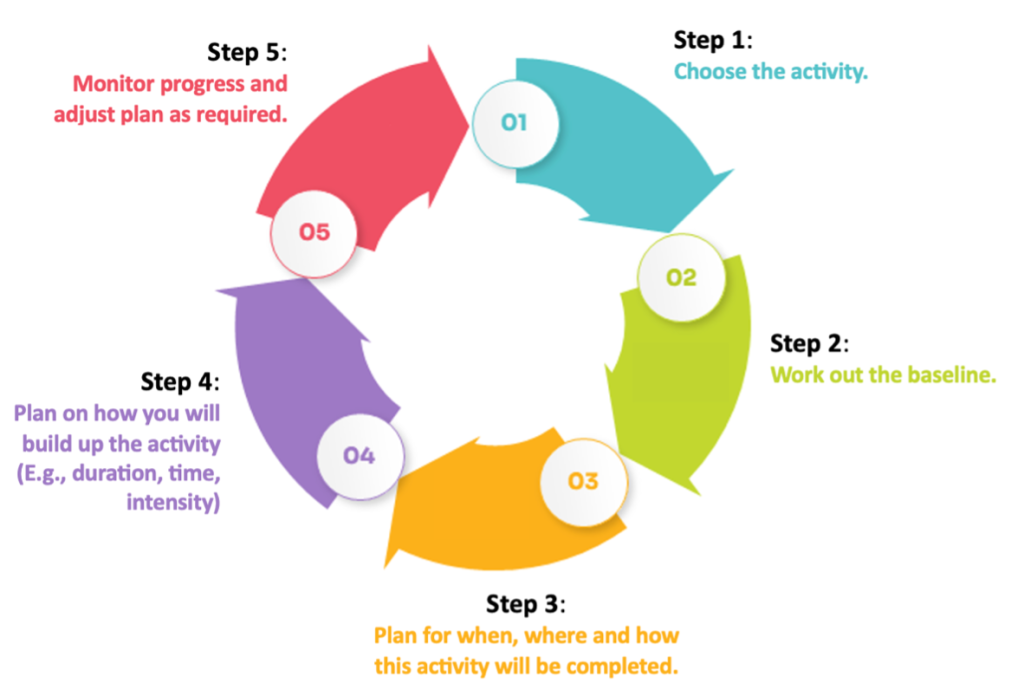

As mentioned before, changing habits and activity patterns can be incredibly challenging. Starting with one or two key areas at a time can offer a sense of control and may help in managing pain and discomfort. Building up by taking small steps can and does add up over time. As shown below, pacing is a continuous cycle of change, re-evaluation and adjustment.

A pacing plan in action

Jennifer worked with a clinician to implement pacing strategies in her daily life. The following process illustrates how the steps in the cycle played a part in increasing her participation.

1. Choose the activity

Jennifer and her clinician discussed the daily activities she wanted to do, and chose to focus on doing the laundry. Selecting a single activity simplified the introduction of pacing strategies and minimised the demands of changing habits.

2. Baseline

It is important to establish a baseline level of participation before introducing pacing. A baseline is the amount of activity that can be done on a good day or bad day, without leading to a flare up or over-exertion [38]. Identify the activities that tend to exacerbate the person's symptoms and assess how long they can do them without increasing either fatigue or pain.

It is crucial not to exceed the persons baseline level of activity to avoid exacerbating fatigue. Determining a baseline can be difficult because symptoms may fluctuate from day to day. To overcome this issue, you may need to monitor activity and participation for the person on both good and bad days over a span of 3 to 7 days, and then calculate the average to determine your baseline level. Once the persons baseline has been assessed, reduce the activity by 20% as your starting point. This ensures they will be able to adhere to the pacing strategy consistently, regardless of whether they are having a good or bad day [39].

For example; Jennifer and the clinician estimate that she can manage around 20 minutes of laundry work before becoming fatigued. The starting point for her pacing strategy is therefore 15 minutes of activity.

Watch the following video (53 secs) for a summary of the process for setting a baseline level of activity.

3. Plan for when, where and how activities are completed.

Clearly define the when, where, and how of your activity. The more specific these definitions are, the more helpful they will be to the person in their plan. Utilise the 3 P's strategy—pace, plan, and prioritise—to effectively integrate these elements into your overall plan [40].

Rest breaks are important and should be scheduled into the pacing plan to lessen the risk of over-exertion and flare-up. Think about what activities are completed during this time, and the amount of rest they offer. They may offer physical rest, cognitive rest or both depending on the person's needs.

For example; Jennifer and her clinician discuss a range of options for rest such as changing positions, going for a short walk and medication. Jennifer likes to physically rest by completing some brief stretching exercises, and she prefers to mentally rest by listening to music. These activities are scheduled into her day, either singly or together.

Other strategies that can help people with Long COVID with planning include:

- Setting a reminder on a phone or in a planner for when activities will occur,

- Inviting a friend or family member to join in

- Creating visual reminders (like sticky notes) in the place where the activity occurs

- Consideration of the order of activities during the day (i.e. which activities naturally flow on from each other?)

- Using AI platforms to automate the planning of activities. These can be programmed to take current activities and other parameters into account.

- Have the plan in multiple formats, such as in a diary, pinned to the fridge and as reminders in a phone.

Jennifer and her clinician came up with the following plan for her laundry tasks. Note the specific detail included in the plan, which makes it easier to judge whether it has been achieved or not. It may seem that this approach is 'micro managing' her day, but a higher level of guidance is needed initially when forming new habits and behaviours.

Jennifer's Action Plan for Laundry

| When? | Every 4th morning at 10am, after breakfast |

| Where? | Laundry at home |

| How? | Total time require for a wash cycle = 1 hour, 28 minutes

Place washing in washing machine (no more than 10 items of clothing) - [5 minutes] REST [5minutes] Place washing powder in washing machine, and start 50-minute wash [4 minutes] REST [2 minutes] COMPLETE OTHER TASK [48 minutes] Get assistance with carrying clothes from machine [4 minutes] REST [5 minutes] Sit down to hang out washing on drying rack, without using pegs [10 minutes] REST [5 minutes} |

| Support Strategies |

|

4. Plan how to grade or increase the activity.

Once the person with Long COVID feels comfortable with the first stage of their pacing program, plans can be made to gradually increase participation over time. Increases in activity must be undertaken slowly and with close monitoring of symptoms and overall comfort. As a guide, activity can be increased by 10% per week [41], but should be paused or even decreased if any signs of PESE or other health issues emerge.

Grading of an activity may be achieved by changing factors such as;

- Time taken or allowed to completed the task

- Distance travelled during activity

- Number of repetitions of movements or tasks

- Addition or subtraction of tasks as part of the activity

- Level of help or support received from others

- Frequency of activity performance

The 3P’s (Pace, Plan, and Prioritise) also provide avenues for grading the activity. Although these graded increments might seem small, they can significantly impact overall energy expenditure and help prevent overexertion and flare-ups. The process of gradually increasing your activity is slow but rewarding. By following a structured approach, you allow your body to adjust and build endurance safely, which can lead to more sustainable improvements in your activity levels over time.

For example; The first 2 weeks of Jennifer's pacing plan have been successful and she feel ready to try and increase her participation in laundry tasks. She wants to decrease the overall time she spends doing this activity, so based on the 10% guideline her rest periods are reduced from 5 minutes to 4 minutes and 30 seconds.

5. Monitoring progress

There are many ways for people with Long COVID to keep track of the progress they make with pacing. Some may like to keep an activity log or booklet, some may choose to map their time visually by downloading the data from their smart watch. Continuous and regular review and adjustment to the pacing plan, in line with the persons individual needs and goals, underpins momentum during recovery and also quickly identifies flare-ups or other problems [42].

For example; Jennifer chose to track the duration and intensity of her laundry tasks in a journal, where she also noted her fatigue (as a score out of 10 after completion). Over a two month period, her fatigue while doing this tasks reduced, but did not disappear completely. However, she was able to complete her laundry tasks in a reasonable timeframe and removed it from the next version of her plan to focus on other activities.

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Sunday | |

| Week 1 | √ 5/10 | √ 5/10 | |||||

| Week 2 | Too tired | √ 7/10 | √ 6/10 | ||||

| Week 3 | √ 5/10 | ||||||

| Week 4 | Too tired | Too tired | √ 5/10 | √ 4/10 | |||

| Week 5 | √ 4/10 | ||||||

| Week 6 | √ 4/10 | √ 3/10 | |||||

| Week 7 | √ 3/10 | Too tired | √ 4/10 | ||||

| Week 8 | √ 2/10 | √ 3/10 |

Activity (20 minutes)

Choose another activity that Jennifer has identified as part of her goals. Work through the following steps to build a pacing plan for this activity. Information in her persona will provide you with some background regarding her baseline level of activity, but feel free to use some creative licence when completing these tasks.

- Choose the activity

- Establish a baseline

- Plan how, when and where the activity will be completed

- Plan on how you will grade or modify the activity

- Plan how you will monitor progress

Pacing plans may vary between the many different daily activities people with Long COVID undertake. Given the various factors that influence daily activities, plans may be slightly different for each of them. This can introduce a lot of complexity into a pacing plan, and therefore careful consideration must be given to how much (or little) you are working on at any one time. It may be helpful to think of the plan as a 'pipeline' where pacing is applied to a selection of activities at any one time. They enter the pipeline as they become a priority, and leave it when the person with Long COVID is comfortable with their performance and participation. The following information gives examples of abbreviated pacing plans for several other activities identified as important to Jennifer.

| Gardening |

|

| Meal Preparation |

|

| Shopping |

|

| Walking |

|

| Study |

|

| Cleaning |

|

Activity (5 minutes)

Reflect on how many of these plans you would implement with Jennifer at any one time. Which do you think she would prioritise as an immediate focus?

Practical tips for staying on track

Working on activity and participation levels can be challenging, but careful planning and strong support networks will help to achieve goals. Here are a recap of proven strategies to help your patients remain on track [43].

- Use a planner or calendar

- Begin by scheduling essential tasks first, including enjoyable activities, exercise, and relaxation time. This ensures the activities that matter most are prioritised within the daily routine.

- Set a timer for activities

- Use a timer to monitor the duration of activity engagement. This will enable the patient to stick to their planned duration, even when they feel particularly energetic.

- Track activity patterns

- Keep a record of activity levels to identify trends and patterns, which can form the basis of adjustments to the pacing plan. However, be mindful that the cognitive load of monitoring and maintaining progress can itself contribute to fatigue and stress. To simplify the tracking process, identify tools or applications to simplify data entry and analysis or share these activities with a clinician or carer.

- Communicate the pacing plan

- Share activity goals with family and friends so they can offer encouragement as part of a wider support system. This can be challenging when the person with Long COVID expeirences misunderstanding or pressure from friends and family, who may need education about the condition and the role of pacing. Specific examples of how energy levels are impacted by particular activities and the specific adjustments required may help, and clinicians can also provide additional information and reinforcement. Setting and maintaining boundaries requires persistence, but prioritising personal health is essential for effective management of Long COVID.

- Establish a realistic progression rate

- While 10% increases may work for some patients, others may find a 2%-5% increase more manageable and effective.

- Practice regularly

- Consistency is the key. Build new habits by incorporating planned activities into the patients daily routine and build momentum.

- Encourage persistance

- It is important for the pacing plan to be followed as as consistently as possible, through good days and challenging days. Consider providing the patient with guidelines for temporary reductions in activity intensity or increases in rest breaks to accomodate their energy levels.

- Create a setback plan

- It is important to acknowledge there will be barriers to the implementation of the pacing plan. Prepare for setbacks by having alternative activities in mind. For instance, if the patient plans to do weeding in the garden, have an alternative indoor activity in case the weather is inclement.

- Use technology to track progress

- A range of applications measure biometrics like heart rate, to help people with Long COVID monitor stability, track symptoms, and observe how lifestyle changes impact their health.

Assessments for monitoring the progress of pacing plans

Along with PESE, other aspects of participation in daily life may need to be assessed and monitored during the implementation of a pacing program. Understanding how everyday activities affect energy levels, health and well-being enables the development of more effective and tailored pacing strategies. A wide range of assessment could be selected depending on the priorities and interests of the person with Long COVID. However, the following assessments provide some general options to consider:

| Outcome | Assessments |

| Participation in Daily Life / Activities of Daily Living | Activity Logs / Time Log Diaries: Activity logs record daily activities (including duration and intensity) to monitor how they affect energy levels and symptoms. Time use diaries record more detailed information about what a person with Long COVID is doing throughout the day, along with where they are doing it and who they are doing it with.

Canadian Occupational Performance (COPM): This tool is designed to capture self-perception of performance and satisfaction in everyday living over time. This assessment can only be completed by Occupational Therapists. Occupational Balance Questionnaire: This tool evaluates a person’s sense of occupational balance in relation to their current situation and daily life. This assessment can only be completed by Occupational Therapists. |

| Functional and Exercise Capacity Tests | Post-COVID-19 Functional Status Assessment (PCFS): This tool was specifically designed for people recovering from a COVID-19 infection, and measures the functional impact of COVID-19 on daily activities.

Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS): This tool assesses the impact of mental health difficulties that can result from developing Long COVID on functioning in work, home management, social leisure, and personal relationships. For more information, go to Improving the participation gap: Physiotherapy for people with Long COVID. |

| Self Management | Occupational Self-Assessment (OSA): This tool captures people's perceptions of their own occupational competence and the importance of various occupations. This assessment can only be completed by Occupational Therapists. |

| Sleep | Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS): This tool evaluates daytime sleepiness to help identify potential sleep disorders contributing to fatigue. |

| Quality of Life | EuroQOL EQ-5D-5L: This tool measures quality of life across five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression.

WHODAS 2.0: This tool assesses health and disability in domains such as understanding and communicating, getting around, self-care, and participation in society. |

Conclusion

Pacing is a deliberate approach to balancing activity and rest, with the goal of gradually increasing activity levels while carefully managing fatigue. Effectively managing Long COVID requires a comprehensive understanding of Post-Exertional Symptom Exacerbation (PESE) and skills in the practical application of pacing strategies. Recognizing and responding to fatigue and PESE is the foundation for maintaining energy balance and preventing over-exertion and flare ups.

Healthcare professionals can more accurately tailor management plans to individual needs by conducting assessments based on both lived experience and formalised screening tools. These evaluations inform sustainable and effective pacing plans which incorporate baseline establishment, detailed planning of activities, and gradual increases in participation [44]. The examples and case studies included in this chapter demonstrate that even small, incremental improvements can lead to significant progress over time [45]. Sharing practical tips such as using planners, timers, and support systems can further enhance the ability of people with Long COVID to manage symptoms and achieve their goals. Pacing is a key strategy in the management of Long COVID [46] and you now have all the knowledge you need to offer it as an option for your patients.

Chapter Key Points

- Pacing is a deliberate approach to balancing activity and rest, with the goal of gradually increasing activity levels while carefully managing fatigue.

- Recognising Post-Exertional Symptom Exacerbation (PESE) is vital for maximising the health and wellbeing of people with Long COVID, with symptoms like feeling "wired and tired" indicating a need for better pacing.

- Healthcare professionals should consider both patient-reported lived experience and formalised assessments of fatigue.

- Patients should track symptoms and energy levels through logs, diaries and/or wearable tech to build evidence about their progress and identify early warning signs.

- Establish a baseline for maximum activity levels, plan activities with rest breaks, gradually increase activity by about 10% weekly (if tolerated), and monitor progress to adjust the plan accordingly.

Additional Resources

For more information and deeper insights, please explore the following resources:

Websites:

Long COVID Physio: This website is a valuable resource for people with Long COVID, offering education, support, and advocacy. It features information on common symptoms, self-management strategies, and pacing techniques to help manage energy levels. The site is patient-led, ensuring accessibility and inclusivity for diverse audiences. It also engages in research and advocacy efforts to improve care guidelines and policies related to Long COVID.

Fatigue Learning Module (Austin Health): This website provides an interactive learning module focused on Long COVID, featuring educational content, resources, and strategies for managing symptoms. It aims to enhance understanding of Long COVID and support individuals in navigating their experiences, promoting effective self-management and recovery through engaging and accessible information.

Activity & Rest Module (Austin Health): The Activity and Rest Module by Austin Health is an interactive online resource designed to educate individuals about managing energy levels through effective pacing strategies. It provides practical guidance on balancing activity and rest, helping users understand how to optimise their daily routines for better health and well-being.

ME Action: This website is global advocacy platform for individuals affected by Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). It focuses on raising awareness, promoting research, and improving care for ME/CFS patients. Key initiatives include organising protests like #MillionsMissing, providing educational resources, and fostering community engagement through projects like MEpedia, a crowd-sourced knowledge base. The organisation emphasises patient empowerment and aims to ensure better recognition and support for those living with the condition.

- Pacing and management guide for ME/CFS

- Pacing and management guide from paediatric ME/CFS and Long COVID

The Royal College of Occupational Therapists (RCOT): The Royal College of Occupational Therapists (RCOT) is a UK professional body advocating for occupational therapy. It supports members through resources, career development, and practice guidance. RCOT emphasises diversity and inclusion while promoting the profession's value in improving health outcomes, and has a strategic plan for workforce expansion through 2035.

- Post viral fatigue and energy conservation

- How to manage post-viral fatigue after COVID-19 - Practical advice for people who have been treated in hospital

- How to manage post-viral fatigue after COVID-19 - Practical advice for people who have recovered at home

- How to conserve your energy

Consumer Lived Experience

ME Support: Navigating ME/CFS and Long COVID: Features the perspectives of seven individuals living with Long COVID and five experts in the field. Through recorded interviews, the site delves into the personal journeys of these individuals, providing in-depth insights into how Long COVID affects their daily lives and routines. This resource highlights the unique challenges and adaptations they face, underscoring the importance of understanding their experiences in developing effective support strategies.

Podcast

Action for Me: This podcast episode features a consumer sharing her lived experience of living with Long COVID. She discusses her journey in collaborating with health professionals to identify effective interventions and strategies tailored to her needs. Additionally, she offers valuable tips for supporting individuals with Long COVID, drawing from her personal insights and experiences.

- World Health Organization. Post COVID-19 Condition (Long COVID) [Internet]. www.who.int. 2022 [cited 2024 Jul 13]. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition ↵

- The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A Long COVID Definition [Internet]. National Academies Press eBooks. 2024 [cited 2024 Jul 13]. Available from: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/27768/chapter/4 ↵

- O’ Mahony L, Buwalda T, Blair M, Forde B, Lunjani N, Ambikan A, et al. Impact of Long COVID on health and quality of life. HRB Open Research. 2022 Apr 22;5:31]. Rehabiliation for people with Long COVID can include a diverse range of interventions, including education about getting high quality rest and sleep and skill building for managing energy levels. All interventions should be founded on individualised approaches to activity and energy management, which establish activity patterns that align with current energy levels and implement mutually agreed self-management strategies that quickly respond to flare-ups or relapse. This can involve identifying potential triggers, temporarily reducing activity levels, monitoring symptoms over time, and avoiding a return to normal activity levels until symptoms have subsided [footnote]Long COVID Physio [Internet]. Long COVID Physio. 2014 [cited 2024 Jul 11]. Available from: https://longcovid.physio/rehabilitation ↵

- National Health Service. Long-term Effects of COVID-19 (long COVID) [Internet]. nhs.uk. 2023 [cited 2024 Jul 15]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/covid-19/long-term-effects-of-covid-19-long-covid/ ↵

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Long COVID in Australia – a Review of the literature, Summary [Internet]. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2022 [cited 2024 Jul 12]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/covid-19/long-covid-in-australia-a-review-of-the-literature/summary ↵

- Long Covid. Long Covid Scotland [Internet]. Long Covid Scotland. 2014 [cited 2024 Jul 14]. Available from: https://www.longcovid.scot/blog/tag/Lived+Experience ↵

- Kunasegaran K, Ismail AMH, Ramasamy S, Gnanou JV, Caszo BA, Chen PL. Understanding Mental Fatigue and its Detection: A Comparative Analysis of Assessments and Tools. PeerJ [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Jul 13];11:e15744. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37637168/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control. Signs and Symptoms of Long COVID [Internet]. COVID-19. 2024 [cited 2024 Jul 14]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/covid/long-term-effects/long-covid-signs-symptoms.html ↵

- Gross M, Lansang NM, Gopaul U, Ogawa EF, Heyn PC, Santos FH, et al. What Do I Need to Know About Long-Covid-related Fatigue, Brain Fog, and Mental Health Changes? Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation [Internet]. 2023 Mar [cited 2024 Jul 14];106(6). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10028338/ ↵

- National Health Service. Long-term Effects of COVID-19 (long COVID) [Internet]. nhs.uk. 2023 [cited 2024 Jul 15]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/covid-19/long-term-effects-of-covid-19-long-covid/ ↵

- 1. Horvath G, Percze AR, Nagy A, Polivka L, Zsuzsanna K, Varga JT, Müller V. Sleep quality in long COVID-19 patients: relation to symptoms, pulmonary function and functional capacity. Sleep & Breathing disorders. 2023 ↵

- Gross M, Lansang NM, Gopaul U, Ogawa EF, Heyn PC, Santos FH, et al. What Do I Need to Know About Long-Covid-related Fatigue, Brain Fog, and Mental Health Changes? Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation [Internet]. 2023 Mar [cited 2024 Jul 14];106(6). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10028338/ ↵

- Faghy MA, Dalton C, Duncan R, Arena R, Ashton REM. Using cardiorespiratory fitness assessment to identify pathophysiology in long COVID - Best practice approaches. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2024;83:55-61. ↵

- Long COVID Physio. Post-Exertional Symptom Exacerbation [Internet]. Long COVID Physio. 2024 [cited 2024 Jul 15]. Available from: https://longcovid.physio/post-exertional-symptom-exacerbation ↵

- Skilbeck L, Spanton C, Paton M. Patients’ lived experience and reflections on long COVID: an interpretive phenomenological analysis within an integrated adult primary care psychology NHS service. Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes [Internet]. 2023 Mar 20 [cited 2024 Aug 4];7(1). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10027259/ ↵

- Accelerate Learning Community. Why is Behavior Change So Hard? [Internet]. Izzo E, Call M, editors. accelerate.uofuhealth.utah.edu. 2022 [cited 2024 Jul 14]. Available from: https://accelerate.uofuhealth.utah.edu/resilience/why-is-behavior-change-so-hard#:~:text=Behavior%20change%20is%20complicated%20and ↵

- Gardner B, Lally P, Wardle J. Making health habitual: the psychology of “habit-formation” and general practice. British Journal of General Practice [Internet]. 2012 Dec [cited 2024 Jul 17];62(605):664–6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3505409/ ↵

- Long COVID Physio. Pacing [Internet]. Long COVID Physio. 2023 [cited 2024 Jul 15]. Available from: https://longcovid.physio/pacing ↵

- Jason LA, Brown M, Brown A, Evans M, Flores S, Grant-Holler E, et al. Energy conservation/envelope theory interventions to help patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Fatigue. 2013;1:27–42. doi: 10.1080/21641846.2012.733602. ↵

- Agency for Clinical Innovation. Chronic pain and brain injury – Boom and bust [Internet]. aci.health.nsw.gov.au. 2021 [cited 2024 Jul 14]. Available from: https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/chronic-pain/brain-injury/fatigue/boom-and-bust ↵

- Neef M. The Neurodivergent Spoon Drawer: Spoon Theory for Autism and ADHD [Internet]. Insights of a Neurodivergent Clinician. 2024 [cited 2024 Jul 16]. Available from: https://neurodivergentinsights.com/blog/the-neurodivergent-spoon-drawer-spoon-theory-for-adhders-and-autists ↵

- Austin Health. Pacing yourself [Internet]. Articulate.com. 2024 [cited 2024 Jul 15]. Available from: https://rise.articulate.com/share/TD6hr7OIRLl5SBrexuCgGcYv0TbaKyn1#/lessons/vrHIKU9Y-O20hZ2a4Nm1Tf_exllqNghi ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. What Is the Spoon Theory Metaphor for Chronic Illness? [Internet]. Cleveland Clinic. 2021 [cited 2024 Jul 16]. Available from: https://health.clevelandclinic.org/spoon-theory-chronic-illness ↵

- Natale G, Pai M. “Spend your spoons wisely”: Conceptualizations of time, energy and aging invisibly with Crohn’s Disease. Innovation in Aging [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2024 Jul 14];5(Supplement_1):600–1. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8968325/ ↵

- FND Hope. Balancing Energy and Pacing [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 15]. Available from: https://fndhope.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Balancing-Energy-and-Pacing-new-FND-copy.pdf ↵

- Ministry of Health. Clinical Rehabilitation Guidelines for People with Long COVID (Coronovirus Disease) in Aoteroa New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health, 2022. ↵

- null ↵

- World Health Organization. (2023). Clinical management of COVID-19: Living guideline, 2023.2. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-clinical-2023.2 ↵

- National Health Service. How to Conserve Your Energy [Internet]. 2023 Aug [cited 2024 Jul 16]. Available from: https://www.qvh.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/How-to-conserve-your-energy-0130.pdf ↵

- National Health Service. How to Conserve Your Energy [Internet]. 2023 Aug [cited 2024 Jul 16]. Available from: https://www.qvh.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/How-to-conserve-your-energy-0130.pdf ↵

- National Health Service. How to Conserve Your Energy [Internet]. 2023 Aug [cited 2024 Jul 16]. Available from: https://www.qvh.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/How-to-conserve-your-energy-0130.pdf ↵

- Long COVID Physio. Pacing [Internet]. Long COVID Physio. 2023 [cited 2024 Jul 15]. Available from: https://longcovid.physio/pacing ↵

- National Health Service. How to Conserve Your Energy [Internet]. 2023 Aug [cited 2024 Jul 16]. Available from: https://www.qvh.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/How-to-conserve-your-energy-0130.pdf ↵

- Royal College of Occupational Therapists. Lift Up Your Everyday - Managing energy [Internet]. Royal College of Occupational Therapists. 2024. Available from: https://www.rcot.co.uk/lift-up-your-everyday/lift-up-your-everyday-by-managing-energy ↵

- FND Hope. Balance - FND Hope International [Internet]. FND Hope International. 2020 [cited 2024 Jul 16]. Available from: https://fndhope.org/living-fnd/healthy-living/balance-2/#1440649454683-b771bca0-51a2 ↵

- Austin Health. Building Up [Internet]. Articulate.com. 2024 [cited 2024 Jul 15]. Available from: https://rise.articulate.com/share/TD6hr7OIRLl5SBrexuCgGcYv0TbaKyn1#/lessons/HfgWLGbV32ABPzoEWn_sim3mZcL5gt8m ↵

- Austin Health. Building Up [Internet]. Articulate.com. 2024 [cited 2024 Jul 15]. Available from: https://rise.articulate.com/share/TD6hr7OIRLl5SBrexuCgGcYv0TbaKyn1#/lessons/HfgWLGbV32ABPzoEWn_sim3mZcL5gt8m ↵

- FND Hope. Balance - FND Hope International [Internet]. FND Hope International. 2020 [cited 2024 Jul 16]. Available from: https://fndhope.org/living-fnd/healthy-living/balance-2/#1440649454683-b771bca0-51a2 ↵

- Botha M. Activity Pacing | Newcastle Integrated Physiotherapy [Internet]. Newcastle Integrated Physiotherapy. 2021 [cited 2024 Jul 24]. Available from: https://newcastleintegratedphysiotherapy.com.au/activity-pacing/ ↵

- Botha M. Activity Pacing | Newcastle Integrated Physiotherapy [Internet]. Newcastle Integrated Physiotherapy. 2021 [cited 2024 Jul 24]. Available from: https://newcastleintegratedphysiotherapy.com.au/activity-pacing/ ↵

- Getting back to what you want to do - young painHEALTH [Internet]. young painHEALTH. 2023 [cited 2024 Aug 2]. Available from: https://youngpainhealth.com.au/pain-management/getting-back-to-what-you-want-to-do/#:~:text=You%20can%20plan%20to%20increase ↵

- Getting back to what you want to do - young painHEALTH [Internet]. young painHEALTH. 2023 [cited 2024 Aug 2]. Available from: https://youngpainhealth.com.au/pain-management/getting-back-to-what-you-want-to-do/#:~:text=You%20can%20plan%20to%20increase ↵

- Getting back to what you want to do - young painHEALTH [Internet]. young painHEALTH. 2023 [cited 2024 Aug 2]. Available from: https://youngpainhealth.com.au/pain-management/getting-back-to-what-you-want-to-do/#:~:text=You%20can%20plan%20to%20increase ↵

- Botha M. Activity Pacing | Newcastle Integrated Physiotherapy [Internet]. Newcastle Integrated Physiotherapy. 2021 [cited 2024 Jul 24]. Available from: https://newcastleintegratedphysiotherapy.com.au/activity-pacing/ ↵

- Long COVID Physio. Pacing [Internet]. Long COVID Physio. 2023 [cited 2024 Jul 15]. Available from: https://longcovid.physio/pacing ↵

- Getting back to what you want to do - young painHEALTH [Internet]. young painHEALTH. 2023 [cited 2024 Aug 2]. Available from: https://youngpainhealth.com.au/pain-management/getting-back-to-what-you-want-to-do/#:~:text=You%20can%20plan%20to%20increase ↵

Involvement in a life situation