1 People

PEOPLE & Creativity

In This Chapter:

Creativity Defined

From me to you:

When I ask people what they think creativity is, they invariably come up with the expression: thinking out of the box. My immediate question is: “Which box?” The answers vary from “the box that limits one’s thinking”, or “the box of ‘normal’ thinking”, or to something similar to Einstein’s definition: “the same type of thinking that created the problem in the first place places a box around the solutions we can find – if we are trying to find solutions we need to get out of that box”. In my mind as author, educator and entrepreneur, I see the box as the limitations society and the massification of education have set up as boundaries to our potentially limitless creativity. By this I mean the restrictions that higher education (possibly and particularly highly analytical and technically robust courses) has created by insisting on getting the “right answers” before learners can proceed to the next level. There are even more restrictive experiences in primary and secondary education (from ages 5 to 18), where “one right answer” is the norm. In sharp contrast, early-life expressions indicate a diverse range of responses to every question and problem. When a 5-year old child finds a stick, they will see it as a magic wand, then a knight’s sword, and a minute later as a gun or a fishing rod, and later still just a stick that lets them play with the dog. When a 15-year-old picks up a stick – it is merely a stick. When a fifty-year-old finds a stick, they might see a possible obstacle someone might fall over or something to get beaten with. So what? My point is that we are boxed by “growing up” and “being educated” to deliver that “one right answer”.

The one right answer is what our good-willed, well-meaning, future-focused parents wish we would regurgitate to demonstrate our progress as learners, to do well at school and to be high-functioning individuals in society. Unfortunately, children quickly learn that there is the one right answer that gets them recognition, positive affirmation and A-grades in school – driving them to conform. The 50-year-old has had so many pain points and disappointments that they might focus on the negative threats, rather than the many opportunities afforded by that stick. Creatives might resist conforming. They might like pushing boundaries and finding new sights in old scenes. This means a lot of creatives live and work slightly outside of the norm and therefore may be a little bit of “a stranger in their own land”. Some of my readers might identify with this feeling or lifestyle. Embrace it: it might just be the X-factor that will open many doors for you as we tread the path towards an ambiguous, volatile, and uncertain future!

Now You:

List a few of your favourite creatives. Can you think of at least from different domains? Have you considered: art, music, literature, movies, PC games, architecture, design, haute couture, make-up artistry, interior design, to name but a few? How about scientists? Are they creative?

Me again:

You are likely to have listed many people who are well known for their creative genius. Do you think that means that creativity is restricted to a handful of artists, musicians, scientists blessed with unusual talents reserved for a few lucky ones? Is it possible that people vary in degrees of creativity and therefore those listed are the geniuses, at the pinnacle where there is only a spot for one or two great minds? Can you (yes you) learn to be more creative? This book is entirely focused on helping you to rediscover your inherent abilities and build those areas perhaps not as well developed as they could be into strengths. As in cooking or video production, one often needs the right tools to improve and deliver output at an excellence level. This book will show you plenty of those too.

Before we even start looking at tools, skills, attributes and the hurdles that prevent us from progressing towards improved creative thinking skills, we need to define creativity in our current context. (Context is critical: e.g., a block of ice in the desert is likely to be more desirable and valuable than a block of ice floating past a survivor on a river raft. Context matters!)

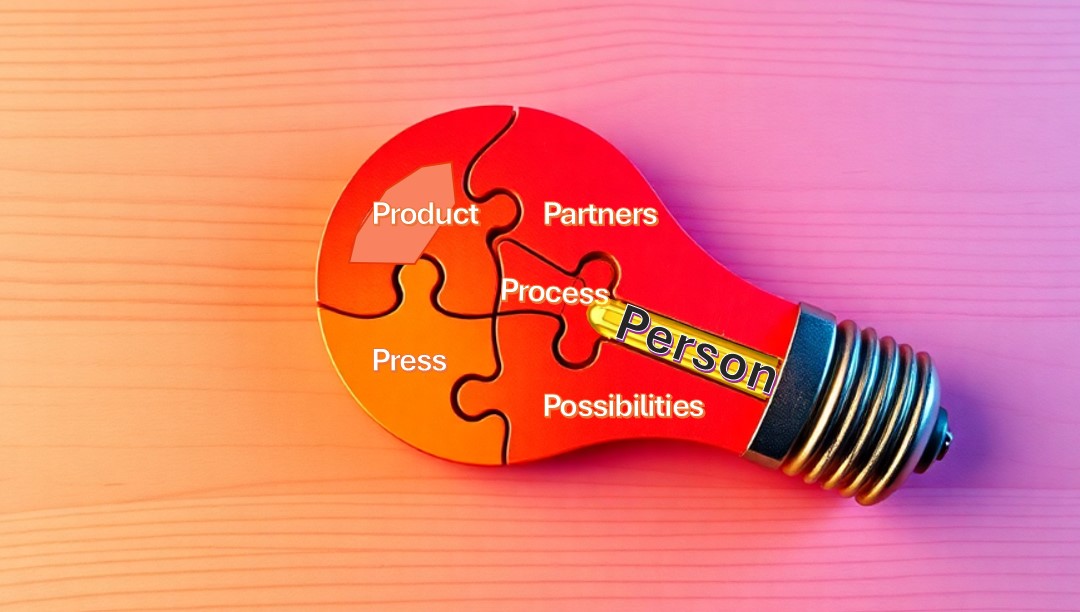

We will consider creativity in the context of work and business more closely. It is quite a tough definition as we need to consider the person (creative genii**), the output (product), the process (how we go about being creative), the context (the press), various partners (collaborators and destroyers) and possibilities (what technology and other tools afford us greater/lesser creativity, e.g. AI). Hence the title of the book: 6Ps of Creativity: How to become a creative leader and develop your creative genii. This book therefore defines creativity as:

The process, within a business context, whereby a person or team of people makes use of a range of skills and thinking tools to create novel, unusual, surprising and appropriate output(s) that can be communicated to others (stakeholders) so that they find surprising value or generative aspects within the output/product.

You might immediately realize that creativity is in the eye of the beholder. And that is totally correct. We all view the world through our own lenses – paradigms created by our past experiences and our future ambitions/hopes and desires. What is creative for one person, might not be so for another. For example, a 3-year old child stating without prompting or earlier guidance that a human is just an animal with clothes, is displaying very advanced thinking. The child is joining dots and getting to new realizations in a novel way – being creative and making associations between remote concepts (more on Remote Associations RA, later). For a 30-year old to make such as statement is neither surprising, nor (possibly) even their own thinking, but might be something they were taught and accepted as “the truth”.

**The term genii is introduced to present both singular and plural nouns for creative people. We introduce ‘genii’—a fusion of “unleashing the inner genie” and the plural of genius. Your inner genii blend rational, emotional, and irrational thinking, navigating multiple domains and collaborating. Emphasising plurality, we acknowledge creative teams, crowds, and multiple intelligences. This book focuses on helping you to unleash your genii and the genii of others.

Divergent & Convergent Patterns of Thinking

In scholarly or scientific literature, creativity is often defined as the ability to generate ideas, solutions, or products that are both novel and valuable. In scholarly views, it encompasses a combination of cognitive processes, personality traits, and environmental factors. Creative intelligence, on the other hand, refers to the capacity to solve problems and adapt to new situations in innovative ways. According to Sternberg’s Triarchic Theory of Intelligence, creative intelligence is one of three components, alongside analytical and practical intelligence (Sternberg, 1985).

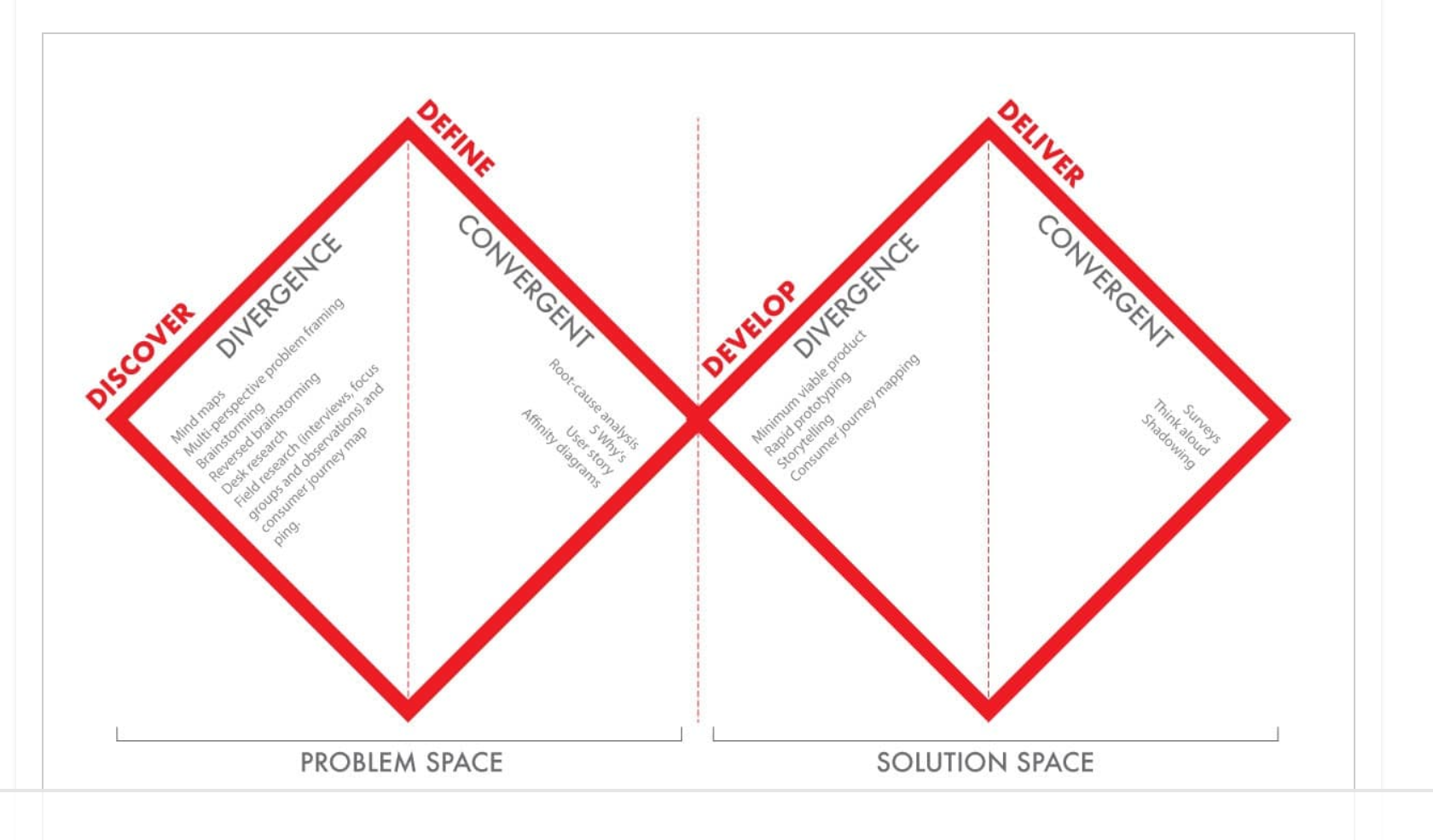

Scientific research suggests that creativity involves both divergent thinking (generating many different ideas) and convergent thinking (narrowing down ideas to find the best solution). Divergent thinking is typically associated with brainstorming and free-flowing thought processes, while convergent thinking requires critical analysis and decision-making skills and is often associated with narrowing down a potentially large number of options to a more suitable, appropriate and useful shortlist. In Design Thinking (DT later in the chapter on Processes), the DT-school facilitators talk about the double-diamond pattern of divergent, convergent thinking (as illustrated in Figure 1.5) which demonstrates that thinkers repeat the two processes of divergent-convergent thinking to get to novel, appropriate, useful and generative ideas.

Guilford’s model of creativity emphasizes the importance of fluency, flexibility, originality, and elaboration in creative thinking (Guilford, 1950; Sisk, 2021). Guilford’s model of creativity highlights four key components in creative thinking: fluency (the ability to produce many ideas), flexibility (the ability to approach problems in various ways and make connections or associations between a diverse range of domains), originality (the novelty or uniqueness of ideas), and elaboration (the ability to expand on ideas with detail). These elements collectively represent creative problem-solving and are the elements that builds the way some creative outputs are assessed.

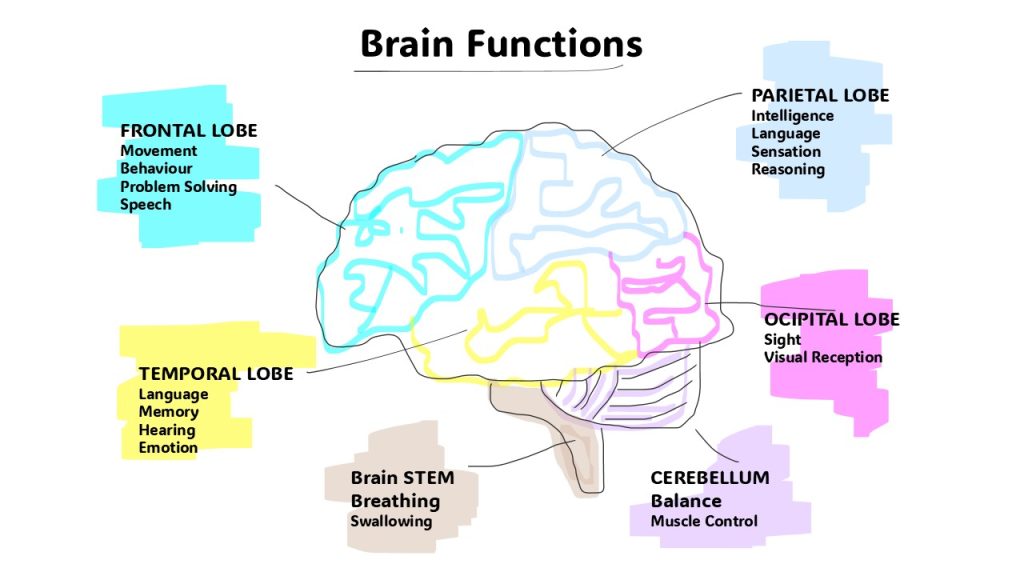

Neuroscientific studies have identified specific brain regions associated with creativity, including the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in planning and decision-making, and the default mode network, which is active during spontaneous thinking and mind-wandering. These findings suggest that both structured and unstructured thought processes are crucial for creative intelligence.

Creative Intelligence (CiQ) is a multifaceted concept that combines creativity and intelligence to produce novel and valuable outcomes. It is a form of intelligence that goes beyond traditional measures of intelligence, such as IQ, by incorporating creative thinking, problem-solving, and innovation. CiQ involves the ability to generate and develop new ideas, as well as the ability to adapt to changing situations and solve problems in unconventional ways.

CiQ is not limited to a specific field or industry and can be applied in many different areas, including art, science, business, and technology. It is a critical skill for success in the modern world, where innovation and creativity are increasingly important in driving progress and growth.

Individuals with high levels of CiQ are often referred to as “creative geniuses” and are known for their ability to produce innovative and ground-breaking ideas. They possess a unique combination of intelligence, creativity, and vision that allows them to see things from a different perspective and come up with solutions that others may not have considered.

In summary, Creative Intelligence (CiQ) is the ability to combine creative thinking, problem-solving, and innovation with traditional measures of intelligence to produce novel and valuable outcomes in any field or industry. It is a critical skill for success in today’s rapidly changing world, and individuals with high levels of CiQ are highly valued for their ability to generate new and innovative ideas.

Who are Creatives? – Attributes & Characteristics

Personality traits also play a significant role in creativity. Traits such as openness to experience, risk-taking, and intrinsic motivation are commonly linked to higher creative potential. Openness to experience, one of the Big Five personality traits, involves a willingness to engage with new and different ideas and experiences, which is fundamental for creativity. The Big Five personality traits, often remembered by the acronym OCEAN, are five broad dimensions of human personality. These traits are widely accepted in psychology and have been extensively studied in scientific literature.

1. O = Openness to Experience: This trait involves imagination, curiosity, and a willingness to explore novel ideas and experiences. People high in openness are often more creative and open-minded. McCrae and Costa highlighted that openness is crucial for intellectual curiosity and aesthetic sensitivity.

2. C= Conscientiousness: This trait reflects a person’s degree of organization, dependability, and discipline. High conscientiousness is associated with goal-directed behaviour and a strong work ethic. It is a significant predictor of academic and professional success.

3. E = Extraversion: This trait encompasses sociability, assertiveness, and enthusiasm. Extraverted individuals are often more outgoing and energized by social interactions. Research has shown that extraversion is strongly linked to positive emotions and overall life satisfaction.

4. A = Agreeableness: This trait reflects attributes such as kindness, empathy, and cooperation. Highly agreeable individuals are typically more compassionate and value harmonious relationships. Agreeableness has been linked to prosocial behavior and successful interpersonal relationships.

5. N = Neuroticism: This trait indicates a tendency toward emotional instability, anxiety, and moodiness. Individuals high in neuroticism are more likely to experience negative emotions and stress. High neuroticism has been associated with poorer mental health outcomes.

Environmental factors, such as cultural and educational influences, can either foster or hinder creativity. Environments that encourage autonomy, provide diverse experiences, and support risk-taking tend to enhance creative abilities. Conversely, environments that are overly structured or punitive can stifle creativity (Amabile, 1996).

In the context of business and management, creativity is vital for innovation, problem-solving, and competitive advantage. We discuss this in more detail in the chapters on Possibility and Press. Creative competence in business involves not only the ability to generate innovative ideas but also the skills to implement and scale these ideas effectively. This requires a blend of strategic thinking, leadership, and collaboration. Companies that cultivate a culture of creativity often outperform their competitors, as they are more adaptable and better equipped to meet changing market demands (Anderson et al., 2014).

Hurdles that Prevent Your Personal Creative Growth

Creativity can be stifled or even destroyed by both little and big things – things that may cause self-doubt, psychological anxiety or pain, or distract you to limit your creative energy or even attempts at being creative. We’ll call these creative hurdles or (following the theme of this book) Pestilences (that kill the 6Ps). I’ve made a list here below in the form of an ABC table. See if you can add some of your own personal 6P-Pestilences in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: The ABC of Pestilence that Pick on Practicing 6Ps of Creativity

|

A-Z of Pestilences |

Fears and Fallacies that Make you Falter |

Your personal pestilence |

|

Age |

You fear that you are simply too young, too old, or not young/old enough, or not born in the right era to be creative. |

|

|

Background |

You believe that one has to have the background, knowledge, and experience to be able to be creative – and you do not have that particular background. |

|

|

Career skills |

Creativity is a career skill – e.g. designers are creative, accountants are not. |

|

|

Dull |

You are feeling dull or you spend too much time in a dull environment that drains your creative spirit. |

|

|

Education |

Your education is all wrong (you do not have the right qualifications or simply too many in one area or too few in the area needed to be creative). |

|

|

Foolish |

Creativity requires a certain amount of frivolity and foolishness – and you don’t have enough of those. |

|

|

Gamble |

Many new and unusual ideas are too much of a gamble to make them worth the effort – it’s better to make small incremental changes. |

|

|

Hardwired |

Creativity is hardwired into one’s genetics and your genetic pool is not filled with creative people. |

|

|

Intelligence |

You believe that you lack the creative thinking or creative intelligence to be as creative as others. |

|

|

Joke |

People may (often) respond to your unusual ideas with put-downs and hurtful banter. |

|

|

Killers |

You feel the many put-downs and hurtful banter you endured in the past, mean that it is not worth the effort to engage in creative think tanks or activities now or in the future. |

|

|

Laughter |

You fear that others may laugh at your ideas or might not take your inventions seriously. |

|

|

Money |

It takes money (and lots of it) to be creative – and you don’t have money to spend on developing or investing in creative solutions. |

|

|

No |

You have heard “no” so often that you are no longer willing to propose creative solutions or new/unusual ideas to the team/others. |

|

|

Opportunities |

You have limited opportunities or creativity or innovation (e.g., professional, age, job scope, authority, budget, etc.) |

|

|

Paradigms |

The team’s different paradigms (boss, participants, partners) get in the way of creativity and inventiveness. |

|

|

Quitters |

You or people around quit trying too soon: once they have one appropriate or workable solution they stop trying. |

|

|

Radical |

Most of your ideas are called “radical” and either ignored or discarded. People don’t really look for new ideas, they just want old ideas in new “boxes”. |

|

|

Stress |

You have much stress in your life to be creative. You have to focus on the crises on your plate and have little or no time to be creative. |

|

|

Time |

There is no time in the day to be creative – there is too much work at the office, and at home there is no space or time for self-development or thinking beyond what’s needed in the immediate moment/ right now. |

|

|

Unappreciated |

You feel unappreciated – and it is anyway mostly the boss’s or your partners’ ideas that get accepted – therefore you have quit trying to be creative for others. |

|

|

Victim |

People around you will simply take your ideas. Seniors often present your ideas as their own and take credit for your inventions or new solutions to problems. |

|

|

Work |

You do not understand that creativity is hard work and requires dedicated attention and development (much like any other skill). You think creativity is a special “a-ha” moment that simply comes to one – or not. |

|

|

Xerox |

You believe that new ideas are just copying from other geniuses’ “old ideas”. You believe that “there is nothing new under the sun”. |

|

|

Yield |

You may believe (in full or in part) that creativity think tanks and brainstorming yield too many useless ideas and are a waste to time: serious thinking is what is required. |

|

|

Zero |

Your job/kids/life simply leaves you little time and energy to be creative. Being creative and building creative competencies are for people with loads of free time or whose jobs demand creativity. |

|

Habits That Build Creative Genii

Creative geniuses exhibit a unique set of attributes, habits, and characteristics that distinguish them from others. One key attribute is their high level of intrinsic motivation, which drives them to pursue their creative endeavours for the sheer joy and satisfaction of the process itself, rather than for external rewards (Amabile, 1996). This intrinsic motivation is often accompanied by a strong sense of curiosity and a relentless desire to explore new ideas and possibilities, as highlighted by Silvia (2008). Creative geniuses also tend to possess high levels of openness to experience, a personality trait associated with a willingness to engage with novel and complex stimuli, leading to greater creativity (McCrae & Sutin, 2009).

In terms of habits, creative geniuses often engage in regular practices that stimulate their creativity, such as maintaining a consistent routine of brainstorming, experimenting, and reflecting on their work. They also tend to exhibit perseverance and resilience, continuing to work on their ideas despite facing setbacks or failures (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996). Additionally, many creative geniuses embrace interdisciplinary thinking, drawing inspiration and knowledge from various fields to inform their work, which enhances their ability to make novel connections (Root-Bernstein & Root-Bernstein, 1999).

Characteristics commonly observed in creative geniuses include high levels of cognitive flexibility, allowing them to shift perspectives and approach problems from different angles, and a propensity for divergent thinking, which facilitates the generation of multiple, diverse ideas (Guilford, 1967). These attributes, habits, and characteristics collectively contribute to the remarkable creative output of individuals considered to be geniuses in their fields.

What I personally found remarkable when reading about and travelling through Spain, Italy and France in the footsteps of some giants in creativity (such as Spanish architect Gaudi; Italian inventor and engineer Leonardo Da Vinci; and highly inventive sculptor and painter Picasso) was their shared habit of keeping visual diaries and sketch books with notes, drawings, doodles and observations. To release your own magnificent inner genii and allow the seeds of creativity to bloom and grow, try the reflective and visual journaling at the end of this book, in our chapter called “the Toolshed”. Invest in a new habit. Daily. You will thank yourself later.

Remote Associates Test for Business Entrepreneurs (Convergent Thinking)

The test below has been designed by AI and is essentially based on the RAT test by Mednick, designed to test creative problem-solving abilities. The selected word lists below is a bit more contemporary, and challenge business entrepreneurs to think about how diverse concepts can connect, helping to develop their ability to see links between unrelated ideas: an essential skill for creative problem-solving and innovation.

60-second Executive Summary (60 ES) of Chapter 1 – PEOPLE-focus:

Creativity and creative intelligence (CiQ) are multifaceted constructs that involve cognitive processes, personality traits, and environmental influences. Scholars emphasise the importance of both divergent and convergent thinking, the role of specific brain regions, and the impact of personal and environmental factors on creative potential. Nurturing these elements, and identifying and limiting hurdles, can significantly enhance individual and organizational creative performance.

References

Amabile, T.M. (1996). Creativity in Context: Update to the Social Psychology of Creativity. Westview Press.

Anderson, N., Potočnik, K., & Zhou, J. (2014). Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1297-1333.

Barrick, M.R., & Mount, M.K. (1991). The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb00688.x

Beaty, R.E., Benedek, M., Silvia, P.J., & Schacter, D.L. (2016). Creative Cognition and Brain Network Dynamics. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(2), 87-95. doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2015.10.004

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. HarperCollins.

Guilford, J.P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 5(9), 444-454. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0063487

Guilford, J.P. (1967). The Nature of Human Intelligence. McGraw-Hill.

McCrae, R.R., & Costa, P.T. (1997). Conceptions and correlates of openness to experience. In R. Hogan, J. Johnson, & S. Briggs (Eds.), Handbook of personality psychology (pp. 825-847). Academic Press.

McCrae, R.R., & Sutin, A.R. (2009). Openness to experience. In M.R. Leary & R.H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of Individual Differences in Social Behavior (pp. 257-273). Guilford Press.

Root-Bernstein, R., & Root-Bernstein, M. (1999). Sparks of Genius: The 13 Thinking Tools of the World’s Most Creative People. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Silvia, P.J. (2008). Interest—The Curious Emotion. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(1), 57-60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00548.x

Simonton, D. K. (2012). Teaching creativity: Current findings, trends, and controversies in the psychology of creativity. Teaching of Psychology, 39(3), 217-222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628312450444

Sisk, D. A. (2021). JP Guilford: A pioneer of modern creativity research. In F. Reisman (Ed.) Celebrating giants and trailblazers: AZ of who’s who in creativity research and related fields (pp. 171-185). Creativity Book Volume VIII. KIE Publications

Sternberg, R.J. (1985). Beyond IQ: A triarchic theory of human intelligence. Cambridge University Press.