3 Process

PROCESS of Creativity

In this Chapter:

Introduction: P3 = Process

Most scholars who study creative genii and creative intelligence (Amabile, Baron, Choi, Kilgour, Pinkow, Runco, and Schilling) agree that generating creative ideas involves combination processes. Creative people are able to take two previously unconnected ideas and combine them in a new way to generate an idea that is novel (surprising), appropriate (relevant), and elegant (aesthetically pleasing). For example, a new creative style of cooking may merge two distinct national cooking styles to develop a unique taste sensation (e.g., Asian Fusion), or an engineer may add appendages to a drone so that it is able to clean high rise buildings or fit new lights to high-rise towers). These combination processes involve combining ideas within our minds that are unique, as they are based upon our individual knowledge bases. As humans with different experiences and backgrounds, we possess different knowledge, and as this knowledge is the basis for developing creative ideas, the human potential for creative ideas is vast. This does not mean that developing, refining, and presenting creative ideas is a simple process, or that everyone demonstrates creative intelligence. While we all have the potential for generating creative ideas, developing highly original and appropriate ideas and getting these ideas accepted by others is a complex process. Humans can obviously be assisted by other humans or AI, by providing new information that we can use as the basis for these combination processes, but it is still the individual that comes up with the new combination (even during prompt engineering) or offers the spark for the creative idea.

To reduce this complexity, it is useful to break the process into stages. Once these critical stages of the creative thinking process are understood, it is much easier to improve your creativity by focusing attention and energy on each stage.

Wallas proposed a four-stage model of the creative process in his 1926 work, “The Art of Thought,” one of the earliest models. His 4-stage model consisted of: (i) Preparation, (ii) Incubation, (iii) Illumination, and (iv) Verification. In the first stage genii define and make concerted efforts to understand the problem. Stage two involves taking a break from actively working on the problem and allowing one’s mind to subconsciously think about the problem and generate new connections. Stage three involves the ‘aha’ moment where there is a sudden conscious breakthrough – a new connection is made. Stage four then involves work around refinement and verification of the new idea. This model is criticised for not being different enough from normal, analytical thinking, but it has been the basis of many new models created by a host of subsequent researchers.

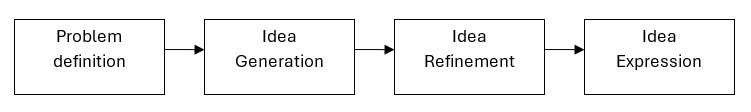

Mark Kilgour proposed the 4-Stages Model of the Creative Thinking Process, as set out in Figure 3.2. The four-stage creative thinking process model incorporates findings from a variety of prominent creative thinking researchers and the related cognitive processes.

These stages of the creative idea development process are iterative, and not as linear as the model might indicate at first sight (Figure 3.2). To help us to think clearly about the thought processes within each stage, it is illustrated as a cyclical and repeated (iterative) process in Figure 3.3.

Thinking of the stages in this consecutive fashion allows us to better understand the thought processes within each step and we therefore separate the stages out. In understanding these, we can develop the tools and cognitive processes particular to each stage. Unfortunately, sometimes thinking habits that help boost creativity at one point can actually hinder it later, i.e. if you get too much detail early on when defining a problem, you might get stuck in a particular way of thinking, known as functional fixedness (FF). This is when you can’t think of new solutions because you’re too focused on the details you already know. For example, if you’re thinking about making a new beverage, you might only think about fruity flavours, sugar and carbonated water, ignoring other options such as teas, herbs, minerals, or perhaps tastes like chilli to stimulate the taste buds without the gaseous carbonated elements.

Adding more detail can be really helpful when you are refining your ideas. It allows you to tweak your concepts and make sure others understand and accept your creative ideas.

Most creativity techniques focus on the second stage, which is coming up with ideas (e.g., brainstorming and think tanks). These techniques usually aim to help you think of more original ideas. The success of these techniques depends on the person or team using them. For example, if someone already knows how to combine ideas creatively, basic training won’t help much. But for someone new to creative thinking, that same training can be very useful. However, if you don’t also work on refining and expressing those ideas, they might only make sense to you and not to others.

Creating great ideas is complex, and the effectiveness of different techniques varies depending on when and how they’re used, and the person’s existing knowledge. Some people think creativity is just something you’re born with, but that’s not true. Like running, while only a few can become Olympic sprinters, anyone can improve their running with training. Similarly, everyone can enhance their creativity with the right techniques. Since the 1950s, studies have shown that creative skills can be developed, and understanding the four stages of creativity can help explain why.

A Creativity Process Model

Stage 1: Problem Definition

Research shows that how a problem is defined greatly impacts the creativity of the solutions. Creative thinking often requires redefining problems to move beyond obvious, existing solutions. For example, simply asking, “Who can clean my windows?” might lead you to hire the same company as before. However, asking, “How can I clean my windows more cost-effectively?” might inspire innovative solutions, such as using drones instead of traditional people-based cleaning services and methods.

Framing the right question is crucial. A well-defined problem can spark creative solutions by forcing us to think outside the box. Conversely, straightforward or overly “ tight” questions often lead to conventional answer. For example, “Which board games could we play when it rains?” will lead to only games being considered, but if the problem is reframed as: “How can we entertain ourselves indoors while it’s raining?” might lead to alternatives such as baking, painting, building Lego cities, using kitchen utensils in a percussion band. By actively redefining problems, we can explore new possibilities and foster creativity. For instance, while early drones weren’t cost-effective for window cleaning in the early days, those who initially considered them gained a competitive advantage as the technology improved.

Research also delves into “problem operators,” which are ways of using existing knowledge versus new information to solve problems. If we rely on past solutions, we tend to come up with routine, uncreative answers. But if we use information from the problem itself, especially if it’s framed unusually, and a little loosely we are more likely to think creatively. Studies indicate that people often default to familiar solutions, even when the problem has evolved. To combat this, it’s essential to actively seek creative problem definitions.

For instance, defining a problem broadly can lead to diverse solutions. Consider the issue of cats killing native birds. Defining it as “too many cats” yields different solutions than “how can we protect native birds.” The former might suggest cat curfews or spaying cats, while the latter could inspire protective measures for birds. Considering a diverse range of different perspectives (e.g., the perspectives of a doctor, urban planner, or hunter, a conservationist for the cat/bird dilemma), can lead to varied problem definitions and, consequently, diverse solutions. For example, the urban planner might think about cat-scapes (areas enclosed and attached to the house so that cats can roam in a restricted area on their own property and not beyond that). The conservationist might offer solutions like moving the birds to an island sanctuary where no wild predators are allowed (e.g., Tiritiri Matangi Island in New Zealand: https://maps.app.goo.gl/bR8pWKLHgbod84Wf8 at 36°36’10.6″S 174°53’34.5″E)

Problem Definition & the Environment

Environmental factors and chance encounters often lead to great inventions. For example, Alexander Fleming’s accidental discovery of penicillin happened when a fungus contaminated his petri dish, leading to the breakthrough of antibiotics. Such serendipity highlights the importance of considering unexpected factors and information.

To enhance creativity, we must intentionally redefine problems. People tend to avoid deep cognitive effort, relying on automatic decision rules even when circumstances change. This is evident when outdated methods persist despite new technologies. To innovate, we must integrate new information and think across domains. Redefining problems encourages us to explore different categories of solutions. Techniques like seeking input from others or considering opposite, contrasting or even directly opposing perspectives help to break habitual thinking patterns. This proactive approach minimizes reliance on random insights and promotes deliberate creativity. As Einstein is quoted to have said: “We cannot solve our problems with the same level of thinking that created them.”

Guilford’s concept of “search parameters” emphasizes that narrowly defined problems restrict creative thinking. Broadening the scope allows for cross-domain solutions and more significant innovations. Narrow problem definitions limit creative potential, while broad, diverse problem-framing fosters creativity. This is often called mental set fixation and is one of the reasons why experts in a certain domain find it hard to escape the domain to be creative beyond their own field of expertise. As an example, when seeking additional exposure for a new product, an expert in media relations is likely to suggest promotions, online media, influencers and PR. Whereas a genii may also include a number of alternatives related to member-seek-member campaigns, sponsorships, partnerships, lead-generation alliances and networks. Another example I often use in my classes is to ask, “What is half of twelve” or “How could we halve 12? Since the very question seems to imply numbers (12 is so obviously a number), students assume that the answer must be 6, or some smarty-pants might say 3*4/2, or 1+5, or 22X 31 or, or even √144*0.5). But these examples indicate a mental set fixation in the domain of numbers. Should one expand the domain (set) to time (hours, months, clocks) the answers already explode into a variety of responses like daylight, lunchtime, and may include the creative response of “too little sleep for healthy living”, etc. Should one further expand the sets to include (say) language, “twelve”, half could be “twe” or “lve”. These are novel, appropriate, elaborate and somewhat surprising creative answers, going beyond mere mathematical calculations within the set of numbers. If one then adds other domains like time (12 hours), sport (12 team members), retail (a dozen eggs) a whole host of new answers come to mind.

Mental set fixation (MSF) as a debilitating factor, is followed quite closely by stopping the thought processes too early, labelled premature ejection. Laypeople literally just stop thinking about creative solutions too quickly. It’s only really when thinkers get beyond 100 (immediate) possible answers that the results enter Big-C territor: beyond the rote, the normal, the routine, to the novel, unusual and surprising. The emphasis is on remote associations. So, the first hundred or so ideas are not remote, but are more likely to be within easy reach of most thinkers of a similar standing and therefore not novel or surprising.

Stage 2: Idea generation

The second stage of the creative thinking process is the one that has traditionally generated the most attention and is often seen (in isolation) as “creative thinking”. The focus is on how creatives can generate creative ideas? We know that creative ideation processes involve combining different areas, concepts from different sets or domains of knowledge. The more unusual those domains the more original will be the new connections.

Divergent thinking, a concept introduced by Guilford in 1967, is all about thinking outside the box and making connections between different ideas. Researchers have been exploring this idea for years, showing how important it is for creative thinking (Kirton, 1976; Scott & Bruce, 1994; Baughman & Mumford, 1995; Schilling, 2005). The follow-up question is: can we teach people to think divergently? The answer is yes! Multiple scientific studies over three decades show that even novices can learn to think this way.

Divergent thinking involves encouraging associative thinking, where you draw connections between unrelated concepts. For instance, experienced creatives in advertising use forced divergence techniques. One might randomly pick a word from a dictionary to spark new ideas, while another might brainstorm the exact opposite of the client brief. These methods help break free from routine thinking (De Bono, 1967; McFadzean, 2000).

However, thinking across different knowledge domains is challenging and mentally demanding. It’s a skill that needs to be built over time. Linking this to problem definition, starting with a broad or unusual problem helps set the stage for creative thinking. For example, the discovery of penicillin by Dr. Fleming showed how a broad problem definition and environmental factors can trigger innovative ideas.

Simonton’s (2003) investigation into creative geniuses revealed that many worked on multiple projects simultaneously, which fuelled their creative breakthroughs. Juggling different projects provides diverse information, fostering new idea combinations. It also highlights the importance of having time to think and make internal connections, a concept known as incubation. It further highlights the critical nature of being willing to invest time to learn about multiple domains and become a specialized generalist (knowing quite a bit about quite a few topics and domains).

Taking breaks and letting your mind wander can help form these distant connections (Wells, 1993). Teaching yourself or your team to generate more divergent ideas is possible through associative techniques. These might involve using random words, metaphors, or other creative prompts. The techniques should match the participant’s skill level – the more experienced they are, the more challenging the technique should be. It stresses the importance of diverse teams with a range of diverse interests and experiences, allowing cross-pollination of ideas and the germination of new interests vaguely related to the problem.

For young entrepreneurs, embracing divergent thinking can be a game-changer. Start by defining problems broadly and experimenting with different techniques to spark creativity. Remember, the more you practice, the better you’ll get at making those unique connections that lead to innovative solutions. Keep an open mind, be willing to explore various domains, and give yourself the time to let those creative juices flow. This approach will not only help you come up with fresh ideas but also ensure they are effective and valuable in the real world.

Many authors and influencers offer insights about using AI to help with ideation and “as a midnight brainstorming buddy” as a good faith way to solve problems and challenging communication, such as writing in the voice of the reader, or making reading more concise and analytical, or less analytical and more a story, when emotional impact is required.

Stage 3: Idea Refinement

Having a wild idea is not enough to be considered creative – everybody has those and sometimes when they see a new product or invention they might even exclaim “I thought of that first”. Creative ideas combine unusual elements, which makes them original. However, making them appropriate and relevant is the hard part. An idea needs to be practical and valuable to others. For instance, a high-protein ice cream for pets may sound good, but if pet owners can produce it easily for themselves, or they do not trust the safety or value, it will not appeal to frugal pet owners. Making an idea relevant is key to the creative process and is often the most challenging part. Even if you see the potential in your idea, others need to see it too. In business, it’s crucial that others appreciate your idea for its impact, feasibility, and potential – not just you.

A new product idea that’s far ahead of current technology is just a novel idea, not necessarily practical. A a great idea that is not practicable or remains unexecuted is just a thought. People can be encouraged to think outside the box, but they must focus resources (time, money energy, effort) to make those ideas workable.

The third stage of the creative process is refining your ideas. This means taking your wild, divergent ideas and making them practical and relevant. After you come up with an initial creative idea, you need to refine it. This involves logical thinking and connecting your new idea back to the original problem or original criteria as set out in the brief (client requirements). It’s about making the idea clear and justifiable.

This “A-ha!” moment happens when you connect two unrelated concepts in your mind. This is also called the moment of “insight” by some authors. The connection between these remote ideas (often from disparate domains) may make full sense to you, but others might not see this connection. If your idea combines very different domains (Big-C ideas), it’s unlikely others will understand its relevance without further explanation. To make others see the value of your idea, you need to refine it. This means developing the links between those different domains so that they make sense to others. It means uncovering and shining a light on the leaps between the domains. This process is called convergent thinking. It involves making the connections clear and logical from the perspective of someone who doesn’t have your expertise. This refinement can take time, especially for very novel ideas.

Generating creative ideas and refining them requires different approaches. Divergent thinking is about making unusual connections and avoiding too much initial information that could limit creativity. On the other hand, refining ideas (convergent thinking) requires understanding how to make them relevant, which involves using information from different domains to develop the idea further.

Both divergent and convergent thinking need strong knowledge bases. You need to know about different fields to come up with creative ideas and to refine them. Divergent thinking techniques can help make unusual connections, but refining those ideas requires in-depth knowledge and sometimes input from experts. This process is not a quick fix but rather a long-term development of knowledge and skills. We cover this diamond of divergent-convergent ideas in more detail in the section on design thinking (DT).

Stage 4: Idea Expression

The final step in the creative process is taking your developed ideas and presenting them for evaluation. While it’s helpful to get feedback from others, the core creative idea usually comes from your own thinking. Once you have a creative idea, you need to share it with others to see if it holds up. Evaluating highly creative ideas can be tricky. While models exist to assess new product ideas, applying evaluation criteria too early can limit creativity. It’s better to evaluate ideas after they’ve been developed and refined, allowing for more originality.

Expressing your novel and unusual creative ideas well is crucial. Even if your idea is new and useful, it must be communicated effectively for others to see its value. Creative ideas are often unusual, making it easy to show their originality but harder to prove their relevance.

Getting others to listen and give feedback early on can help refine your ideas. Sharing your ideas with knowledgeable people can provide valuable insights and help you improve them. This process might involve multiple stages of feedback and an iterative process of idea and message refinement. (See the chapter focussed on the Expressing/Persuasive/Appropriate P of Creativity.)

Most creative ideas fail not because they’re bad but because they’re poorly presented. You need to be able to explain and showcase your ideas in a way that others can understand and appreciate. This involves good storytelling and presentation skills to cover heart, mind and wallet. These short phrases capture the full meaning or addressing emotional needs, cognitive (knowledge and thinking) needs and value (financial and functional) needs of the decision-makers or intended clients. Good story-telling that demonstrates the hidden drivers and anticipate users/decision-makers fears are essential. I therefore devote an entire chapter to these critical skills of persuasion and influence for genii (Chapter 5).

It is critical to mention the key traits genii will have to develop alongside the thinking processes. Creative individuals often need high self-confidence, some willingness to not have to confirm to societal norms, and resilience to handle rejection. It’s important to keep trying and refining your ideas. Creating an environment that encourages idea expression and accepts failure is crucial for fostering creativity. By understanding these steps and traits, you can increase the chances of your creative ideas being successful.

In summary

It seems some of the biggest problems with creative thinking are not a lack of intelligence or ability, but rather the processes people follow, further complicated by mental set fixation (MSF), over-analysis and prolonged or intensive data gathering in the early stages of the process, premature ejection (PE), and most unfortunately after the entire creative process, their inability to present or sell new solutions!

We discuss another tried and tested process that is particularly useful for business executives and new product developers. The Design Thinking Process (DT) is covered briefly in the following sections. (You may also want to refer back to Edward de Bono’s 6 Thinking Hats as a generalized creative process to use in various creative think tanks and business meetings.)

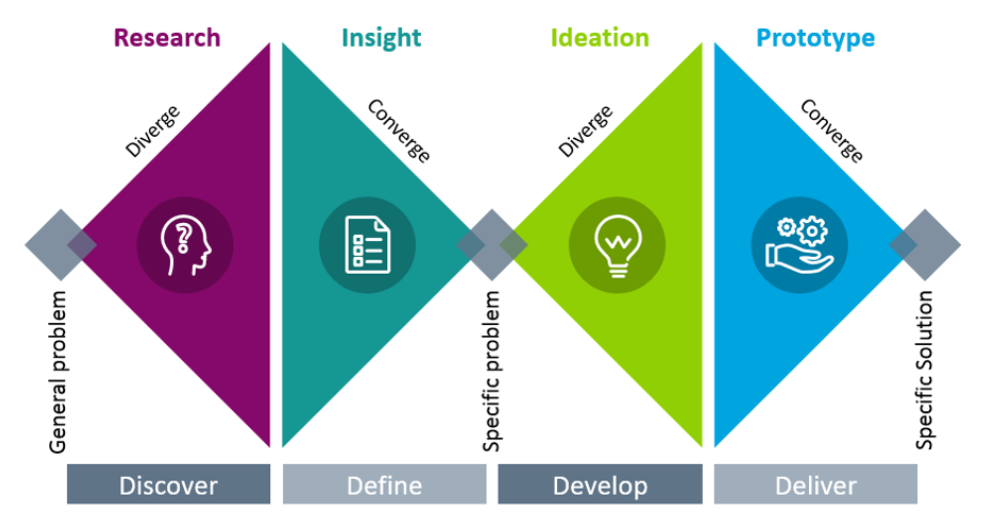

Double diamond process of Design Thinking (DT)

DT is a shift in our way of thinking and a collection of hands-on methods and tools, Various top business schools (Harvard, MIT, Stanford) and DT Academies offer a range of stage-based processes, but to focus our attention and for ease of learning and retention, I cover the DT iterative process here. In my experience this is a very useful process for business executives who lead multi-disciplinary teams of innovators, ideators, intrapreneurs and other problem-solving roles.

Traditionally, design focused on physical objects. Nowadays, as Professor David Keller from Stanford Business School explains, Design Thinking (DT) is seen as a powerful tool for solving tough problems and driving innovation. DT involves a double-diamond process that helps creative thinkers address various aspects like context, needs, and capabilities to refine problems, explore solutions, prototype, fail quickly, and improve for practical outcomes. Tim Brown, CEO of IDEO, says designers use DT to solve many creative and business challenges, such as developing new strategies, markets, products, and services. Major brands like Adobe, Apple, Google, and McDonald’s use DT.

Thinking Styles

Before we get into the nitty-gritty of the process, it’s prudent to cover the thinking styles that make DT such a powerful and advanced creative thinking process.

Design thinking (DT) is about how we process information and solve problems, emphasizing a human-centred approach. This means understanding and empathizing with users, thinking through doing, and using both creative (divergent) and practical (convergent) methods. DT involves observing and collaborating with customers to deeply understand their needs. DT is primarily about balancing human needs with business goals and exploring new possibilities beyond current knowledge. It’s driven by the desire to innovate and find new opportunities, understanding that there is no single answer to a problem. Defining the problem clearly and understanding the context is vital. DT teams often reframe problems to see them from different angles. They use integrative thinking to balance different ideas and constraints, aiming for solutions that combine the best elements of each idea.

DT is a step-by-step process where you constantly create and test prototypes to quickly learn and improve. This method helps bring ideas to life and explore various solutions. Instead of just discussing ideas, DT encourages taking action and engaging with real users to inspire new thinking. Further, visualization is key in DT. Designers use symbols, models, and mock-ups to make ideas understandable and to show how different elements interact. Collaboration is also crucial, involving diverse teams and stakeholders to find a wide range of solutions.

Lastly, two key ways of thinking in design thinking (DT) are integrative and abductive thinking. Integrative thinking involves balancing different ideas to create a better solution that combines the best parts of each. It means considering technical, business, and human aspects to find a well-rounded answer. DT balances user needs with business goals and mixes practical and creative thinking. In contrast abductive thinking is about exploring new possibilities beyond current knowledge. It challenges existing ideas and norms, aiming to create something new and find fresh opportunities. Tim Brown highlights that DT recognizes there’s no single answer to a problem. Instead, it’s about exploring and balancing different ideas to innovate effectively.

Practices of DT

The “practices dimension” of Design Thinking (DT) involves specific activities, tools, and ways of working together. Key elements include:

- Human-centred approaches: Focusing on solving problems for people.

- Thinking while doing: Learning and solving problems through action.

- Collaboration: Working together in multi-disciplinary teams.

- Visualizing and prototyping: Making ideas tangible to test and improve them.

- Divergent and convergent thinking: Generating many ideas and refining them into solutions.

DT emphasizes putting people first, considering all stakeholders, especially those with the problem that needs the solution. Practitioners explore various problem statements and solutions, using a rapid, systematic, and continuous process of prototyping, testing, and redesigning. This iterative approach helps formulate ideas, share knowledge, and facilitate discussions by demonstrating and making concepts tangible.

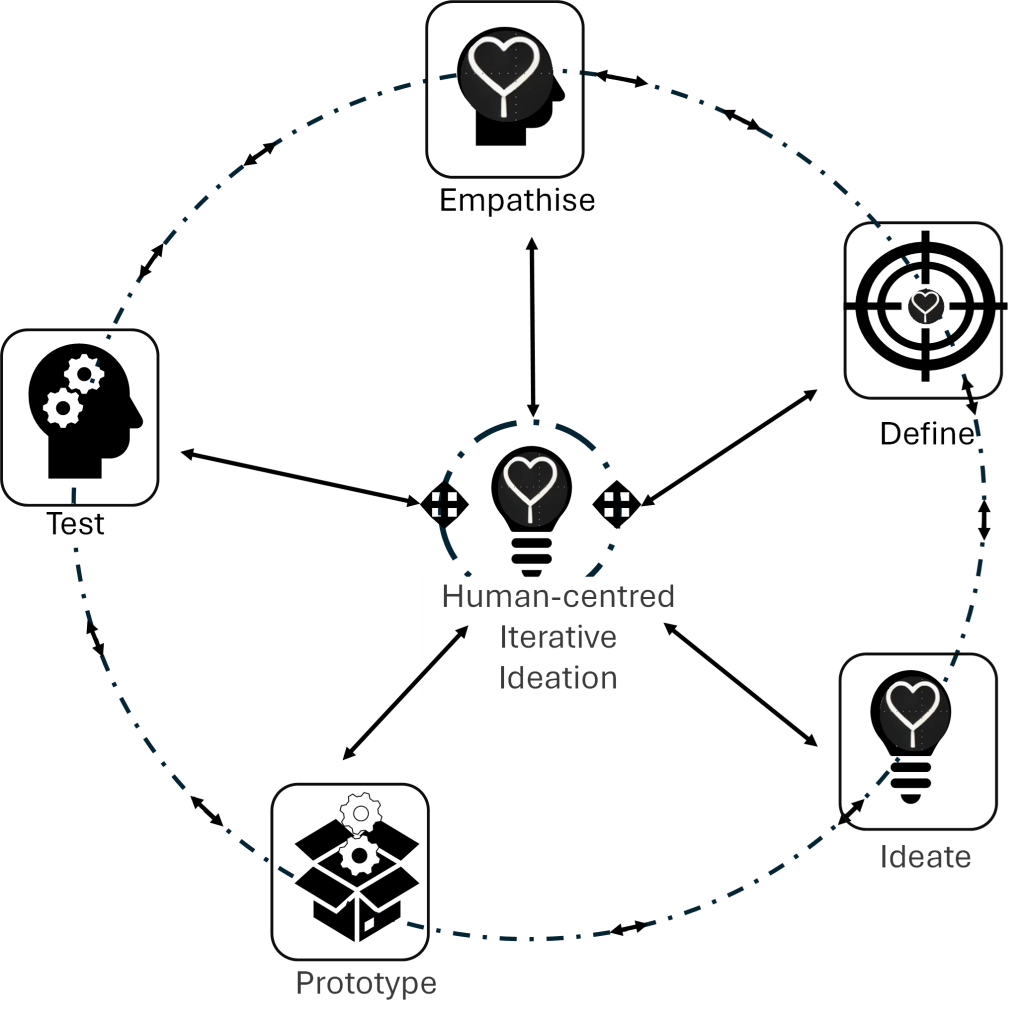

The Five Stages

DT tackles complex problems in five iterative stages, with the key to the iterative process is to constantly visit and revisit pure unimpeded understanding of the human(s) at the centre of the problem:

- Empathizing: Understanding the human needs involved.

- Defining: Re-framing and defining the problem in human-centric ways.

- Ideating: Creating many ideas in ideation sessions.

- Prototyping: Adopting a hands-on approach in prototyping.

- Testing: Developing a prototype/solution to the problem.

Stage 1: Empathise

Design thinkers (DTers) focus on understanding the context of the problem they need to solve, emphasizing a human-centred approach. This means deeply understanding the needs and desires of all stakeholders, especially the end users.

Empathy Building

DTers actively try to understand the feelings, values, and experiences of users. DTers make every “effort” to see the world through the eyes of others, understand the world through their experiences, and feel the world through their emotions”. Tim Brown suggests:

- Conducting interviews

- Shadowing customers and users

- Using the product themselves

- Engaging non-judgmentally to see and feel the world through others’ perspectives.

Tools for Understanding:

- Customer Complaints: Reading and analyzing complaints to identify issues

- Interviews and Observations: Engaging with users to gather insights

- Immersive Experiences: Experiencing the user’s context first-hand through methods like mystery shopping and shadowing

- Empathy Map: Developed by Dave Gray, this tool helps organizations understand customer experiences and expectations.

A practical example: Flight Onboarding: To understand customer frustrations, research both frequent flyers and first-time travellers to improve the booking-in process by enhancing good experiences and minimizing bad ones.

Refining the Problem Statement:

After gaining insights from these activities, DTers refine the original problem statement. This refined statement then guides the next phases of solving the problem, ensuring solutions are tailored to the actual needs and experiences of users.

In summary, design thinking involves deeply understanding users’ perspectives through various empathetic actions and tools, leading to better problem definition and more effective solutions.

Stage 2: Define

The Define Phase in design thinking is about organizing and making sense of the data gathered to create a clear problem statement. This phase involves understanding the context, needs, and desires of users and stakeholders. Here’s a simplified breakdown for young entrepreneurs:

Gather Insights:

- Collect various perspectives and analyze user needs.

- Study the initial problem thoroughly.

Create Outputs:

- Develop a mutually acceptable problem statement.

- Use methods like Story-share and Capture, and Structuring Insights to synthesize team learnings.

Story-Share and Capture:

- Teams share insights from interviews and observations.

- Write key points on sticky notes and group them into themes.

- Discuss recurring themes to generate new ideas and solutions.

Structure Insights:

- Turn findings into actionable insights.

- Identify causes behind observed behaviors to better respond to design challenges.

- Ask questions to determine the quality of insights and how they can influence design.

Problem Statement:

- Define a clear problem to guide the team.

- Make sure the problem is the right one before finding solutions.

- Identify key users (groups with fairly homogenous needs) and their needs.

How Might We (HMW) Questions:

- Frame the problem as “How might we…?” to inspire solutions.

- Use HMW questions to turn insights into actionable challenges.

- Ensure questions are broad enough to inspire creativity but focused enough to provide direction.

Personas:

- Create fictional characters representing different (real-world) user types.

- Use personas to understand user needs, behaviors, and goals or target groups.

- Personas help guide the design process and ensure solutions meet user needs.

Tools for Understanding Users:

- Interviews and Observations: Talk to users and observe their behaviour to gather insights.

- Immersive Experiences: Engage in activities like mystery shopping and shadowing to experience user contexts firsthand.

- Empathy Map: A tool to visualize and understand user experiences and expectations. (See the Toolshed).

The Define Phase helps design thinkers clarify the problem and understand user needs deeply. By using methods like Story-share, Structuring Insights, HMW questions, and Personas, teams can develop meaningful and effective solutions that resonate with users. This process ensures that the solutions are not only innovative but also relevant and practical for the end users.

Stage 3: Ideate

In the Ideate phase, designers generate a wide range of possible solutions after analyzing observations from the Empathy and Define stages. They focus on idea generation using techniques such as analogical thinking, brainstorming, Braindumping, BrainWriting, BrainSketching, metaphorical thinking, ideation heuristics such as Random Word Technique (RWT), SCAMPER, Worst Possible Idea, CUPPCO and many more. (For a range of tools and their application see the Tools Shed at the end of this book). The goal is to come up with as many potential solutions as possible. Towards the end of this phase, prototyping is used to test the suitability and effectiveness of these ideas, helping to identify and overcome any barriers to implementation. So, the main purpose of the Ideation stage is to generate as wide a range of potential solutions using creative techniques as possible.

Stage 4: Prototype

Prototyping involves creating an early, inexpensive version of the product to test its functionality and identify any issues. It helps users visualize the solution and provides valuable feedback on how they think and feel about it. Prototypes can be refined based on user experiences and feedback, helping the team improve the design before moving forward. Create early versions of the product to test and refine ideas. In the words of Ideo’s CEO Tim Brown:

“By taking the time to prototype our ideas, we avoid costly mistakes such as becoming too complex too early and sticking with a weak idea for too long.”

Stage 5: Test

In the Test phase, designers rigorously test the most promising prototypes. This phase aims to deepen understanding of how users interact with the product and identify any remaining problems. Feedback from users is crucial to ensure the solution is practical and effective. Both qualitative and quantitative research methods, such as surveys and usability tests, are used to gather insights and refine the product further. It is important to rigorously test prototypes to ensure they meet user needs and identify any issues before final implementation.

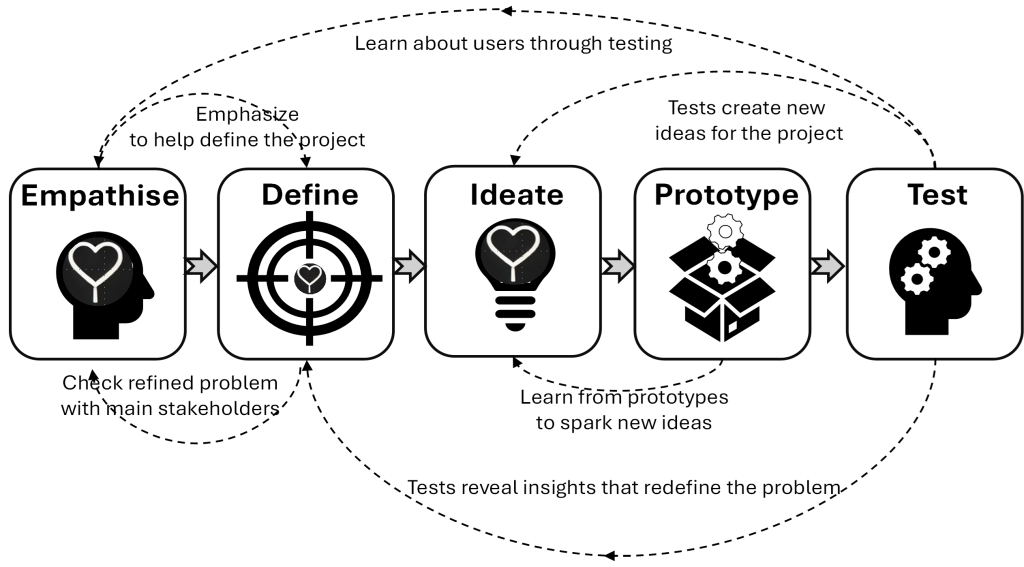

Note that these stages are not linear, but iterative. This means that practitioners of DT often return to previous stages to correct or adjust their thinking or erroneous perceptions because of new insights gained from the next stage. For an illustration of this iterative process and how insights are improved and incorporated into the next stage, see Figure 3.10.

Uniquely Personal Processes

Although the two processes above seem highly standardized and even formulaic, in my experience creatives follow their own uniquely adapted processes to optimize the way they interpret the brief (what the client says they need or perceive the problem to be), but they share five common themes as indicated in the processes above: (i) genii spend a large proportion of their creative time on planning, interpreting and understanding the needs of the client/user or person with the problem. Albert Einstein is reported to have said: “If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and five minutes thinking about solutions.” (ii) Adept creatives look for inspiration and ideas in a wide range of domains and often refer to nature and other genii’s work (in the same or alternative domains), to selectively borrow ideas with merit, both as inspiration and for instigation (providing a starting point). For example, trying to solve a problem with building a tunnel, engineers might look at how earth worms or badgers, foxes and rabbits burrow tunnels and learn from those experts. (iii) Genii understand and invest in the hugely useful process of “incubation”. Incubation is a valuable tool for boosting creative thinking. It involves taking a break from actively trying to solve a problem and allowing your mind to wander. During this period, your subconscious mind continues to work on the problem without the pressure of focused thinking. This can lead to unexpected insights and fresh ideas when you return to the task. Essentially, incubation gives your brain time to make new connections and come up with creative solutions that might not emerge during concentrated effort. (iv) Iterative thinking, rethinking, and meta-cognitive processes. Reflective and meta-cognitive thinking processes are crucial for creatives as they involve evaluating one’s own thought processes and strategies. When engaging in meta-cognitive processes, one monitors and assesses one’s own thinking, recognizing strengths and areas for improvement. This self-awareness helps in identifying effective strategies, learning from past experiences, and adapting to new challenges. By reflecting on their creative processes, individuals can better understand what methods work best for them, leading to more efficient and innovative problem-solving. In essence, meta-cognition allows creatives to fine-tune their approach, enhance their skills, and produce higher-quality work. (v) Most of the creatives I work with are fully aware of the role of incubation – just letting the ideas simmer away in the subconscious mind. Some genii take a brief nap (NASA suggests 26 min to fully refresh and rewire); others play a game or do something with their hands (fold origami, mould clay, play racquet ball or darts – some kind of fine motor skills are used); and still others pretend they are some part of the problem. They visualize themselves as some object that is right in the middle of the issue and try to think “like a cog in the wheel”. Finally, (vi) creative genii appreciate and embrace the criticality of diverse thoughts and actively pursue alternative viewpoints, partnerships with a diverse range of participants and broaden their access to a range of expertise in multiple domains. Creative minds are curious and restless in their pursuit of new and interesting ideas. In my experience creatives read widely and actively seek the latest developments and trends in their domains and those closely related (e.g., a fashion designer will not only study new fabric and innovations in fasteners and accessories, but will also read up on new hairstyles, make-up, body-shaping and related body-image enhancements.)

In summary, as you progress on your journey as creative, you will have to test and re-test methods and processes that align best with your natural learning and thinking styles. The bases offered by Kilgour’s and DTers’ processes are useful to establish starting points but do not feel in any way limited or excluded from finding your own creative rhythm – including when and where to allow for periods of incubation and reflection.

60-second Executive Summary (60 ES) of Chapter 3 – PROCESS-focus

Creativity relies on two main thinking competencies: divergent and convergent thinking. Creatives follow uniquely personal, iterative processes, which allow for periods of incubation and deliver remote associations over a diverse range of domains. Genii constantly reflect, iterate – revisiting problem definitions and solutions to emphasize with the stakeholders. Involving teams of people with diverse interests is an integral part of best practices.

References

Amabile, T. M. (2017). In pursuit of everyday creativity. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 51(4), 335–337. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.200

Chavula, C., Choi, Y. & Young, S. (2022). Understanding Creative Thinking Processes in Searching for New Ideas. CHIIR ’22: Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Human Information Interaction and Retrieval, pp 321-3 https://doi.org/10.1145/3498366.3505783

De Villiers, R. (2025). Firefly generative AI to produce picture. Prompt here: A breathtaking, stylized frog on a rock in the middle of a calm but flowing clear river, surrounded by yellow-green new trees and lime green ferns and orange wild flowers. The frog has large friendly eyes and seem to know a secret, expressive, large eyes. The background glows yellow, light green and turquoise colours and the frog’s colours complement the hopeful and light theme of the picture and accents. The artwork features a painterly style with vibrant yellow lime green and turquoise green hues, capturing the joyful and hopeful light spirit of the happy frog.leap

Dam, R. F. and Teo, Y. S. (2024, December 3). What is Design Thinking and Why Is It So Popular?. Interaction Design Foundation – IxDF. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/what-is-design-thinking-and-why-is-it-so-popular

Kilgour, M. (2022). Creative Thinking: Designed for Humans. In R. De Villiers (Ed.) (2022). The Handbook of Creativity & Innovation in Business. (pp. ). Springer.

Mumford, M. D., Blair, C., Dailey, L., Leritz, L. E., & Osburn, H. K. (2006). Errors in creative thought? Cognitive biases in a complex processing activity. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 40(2), 75–109. https://doi. org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.2006.tb01267.x

OpenAI. (2025). Scientist observing a petri dish through a microscope in a 1930s laboratory setting [AI-generated image]. DALL·E. https://chat.openai.com

OpenAI. (2025). Stylized representation of the word “TWELVE” [AI-generated image]. DALL·E. https://chat.openai.com (Prompt: old, artistic typography. The design incorporates dynamic colours, geometric shapes, and Xii and the number 12)

Runco, M. A. (2012). Divergent Thinking, Creativity, and Ideation. In J. C. Kaufman & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.). The Cambridge handbook of creativity (pp. 413–446). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511763205.026

Runco, M. A. (2015). Meta-creativity: Being creative about creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 27(3), 295–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2015.1065134

Sadler-Smith, E. (2015). Wallas’ Four-Stage Model of the Creative Process: More Than Meets the Eye? Creativity Research Journal, 27(4), 342-352 https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2015.1087277