Chapter 8: The Power of Summary: Understanding Others’ Ideas and Using Those Ideas Ethically

Michael Cop and Janel Atlas

This chapter looks at why you might summarize and provides you examples of how you might summarize:

8.1 You Are Part of a Bigger Conversation: Quoting, Paraphrasing, and Summarizing discusses the importance of summary to your university studies and distinguishes the ways of using others’ information

8.2 Summary: A Pineapple, Grape, and Banana Walk into a Bowl takes you through a step-by-step process for summarizing

8.3 Should You Summarize with AI Technology? highlights the strengths and weaknesses of using programs such as ChatGPT

8.4 To Summarize Effectively, You Must Read This argues for the single most important process in summary writing

8.5 What You Read May Structure What You Write shows the importance of genre: different genres have different conventions that can help shape a summary paragraph

8.6 Out of Cite? not only shows you how to cite information but also discusses the perils of not citing

8.1 You Are Part of a Bigger Conversation: Quoting, Paraphrasing, and Summarizing

When writing in academic settings, you read and respond to the ideas written and published by others. The core of academic writing–and what sets it apart from posting a comment online, texting or emailing a friend, or composing an entry in a personal journal–is that scholarly writing enters into conversation with the thoughts and arguments of other writers. It therefore also acknowledges to whom those thoughts and arguments belong.

There are (at least) three good reasons for citing sources of those thoughts and arguments in your work:

- To avoid plagiarism (copying the work and ideas of others without properly crediting), to gain credibility for yourself as a writer and thinker, and to make your own argument better.

- To make reading easier for your readers by providing them not only with information about what ideas you have gathered from elsewhere, but also, through correct citational practices, how they can track back and find your sources to read them firsthand.

- To give credit to those who have already done the research, thinking, and writing that laid the groundwork for you to be able to benefit from that work.

Because much academic writing requires you to express your own ideas within the context of the published writing of others, you’ll want to know how to include those ideas and words of others smoothly and honestly. How do you determine whether to include a large chunk of an article, a summary of the author’s main point, or a specific quotation in your paper?

In The Craft of Research, Booth et al. suggest the following guidelines for answering that question:

- Summarize when you want to refer to a text but the specific details of the article are not important to your argument. (See section 8.2 of this chapter for more details about writing an effective summary.)

- Paraphrase (put into your own words a key point or fact) when you can briefly point to the evidence in the other person’s writing that is pertinent to yours (2016, 200).

In contrast, a quotation is an exact word-for-word copy of what is in the reference text you are using. There are several good reasons to quote verbatim, according to Booth et al.:

- The literal words provide you with good evidence for supporting your argument.

- The source of the words is a recognized authority on the subject you’re writing about, and therefore quoting their thoughts will lend credibility to your ideas.

- “The words are strikingly original or express your key concepts so compellingly that the quotation can frame an extended discussion” (Booth et al. 2016, 200).

- You disagree with the point in the source and in order to respond to it and make your point, you want to make sure to state it ‘exactly’ as it appears in the original text (Booth et al. 2016, 200).

Importantly, if someone’s thoughts or arguments are valuable enough that you want to include them in your written work, you’ll need to provide a conceptual bridge or link so that your reader can understand why those thoughts or arguments are there. Otherwise, they are just ‘dropped in’ like a bomb, and the reader has to try to puzzle out what they mean and why you’ve quoted, paraphrased, or summarized them, which makes them less likely to have the positive effect you were hoping they’d have in service to your argument.

8.2 Summary: A Pineapple, Grape, and Banana Walk into a Bowl

When you summarize a text, you condense it, showing in brief its overall argument/point or how its examples interrelate. Part of this process is superordination, or “constructing a more general conceptual framework from the analysis and synthesis of specific information” (Kirkland and Saunders 1991, 110). In some ways, then, summary writing is pattern recognition: you look at how extended portions of text form patterns or groups or at how those portions of text are conceptually similar. As your brain recognizes patterns all the time, you likely already have some of the necessary underlying skillset to summarize effectively.

Take the following three images in Figure 1 as an example: how are these three items similar?

The differences between the items in Figure 1 might be more apparent than the similarities. For example, their colours and shapes differ. Two of the items need to be peeled before they can be eaten, but the other one has edible skin. Two grow in bunches, while the other grows individually. One grows on a flowering plant, one grows on a vine, and one grows on a tree. Despite these differences, though, you will likely have identified that they are all fruit. That is, you looked past their differences and towards the essence of the items–the ways that the three items are conceptually similar.

Let’s try again, this time in stages. The first step is largely the same process as the fruit example: classification. What is a collective term for the three bigger items in Figure 2–car, bus, and train?

You may have recognized that all three are motorized means of moving people and have therefore chosen a term such as vehicle or a phrase such as modes of transportation. If you were writing a summary sentence of these three pictures, this word or phrase would be a good place to start: make it your grammatical subject (if you need to remember grammatical subjects, revisit Chapter 6):

The vehicles…

Next, you need to say something about that particular group of vehicles: what common action or state do they share? This action or state would be your verb and object (i.e., predicate).

The vehicles have broken windows.

These previous two examples may have seemed obvious to identify an underlying concept or to categorize because you were making observations about discrete items that have clear physical referents, but the process behind those two examples is the same as for summarizing verbal texts.

To illustrate, let’s try a similar exercise with a paragraph from George Monbiot’s “Beholden to the Mob”, an article about how big grocery chain stores in the United Kingdom can affect the food market:

In 1981, the Monopolies and Mergers Commission decided that the way in which the superstores twisted the arms of their suppliers to extract special concessions was “beneficial to competition and to the consumer”(2). In 1985, the Office of Fair Trading announced, to the amazement of those who supplied the big chains, that it “was unable to identify any particular case which amounted to an abuse of buying power or other anti-competitive practice.”(3) In 1996, after discovering that the superstores were engaged in predatory pricing – driving bakeries out of business by selling bread at less than the cost of production – it decided to take no action.

…

2. Monopolies and Mergers Commission, 1981. Discounts to Retailers. The Stationery Office, London.

3. Office of Fair Trading, 1985. Competition and Retailing. The Stationery Office, London.

Mobiot, George. “Beholden to the mob.” 14 March 2006. https://www.monbiot.com/2006/03/14/beholden-to-the-mob/

As with the fruit and vehicles examples above, the Monbiot paragraph has similar items. While we put the pictures side-by-side for you in the fruit and vehicles examples, you can assume that writers often put items of similarity beside each other within paragraphs–as Monbiot does here. Paragraphs are groupings of similar ideas or examples.

If you re-read the Monbiot paragraph, you will see the following three related items:

[One] In 1981, the Monopolies and Mergers Commission decided that the way in which the superstores twisted the arms of their suppliers to extract special concessions was “beneficial to competition and to the consumer”. [Two] 1985, the Office of Fair Trading announced, to the amazement of those who supplied the big chains, that it “was unable to identify any particular case which amounted to an abuse of buying power or other anti-competitive practice.” [Three] In 1996, after discovering that the superstores were engaged in predatory pricing – driving bakeries out of business by selling bread at less than the cost of production – it decided to take no action.

When you summarize, your job is to see how such items relate to each other, which you can do by following a similar process to the process that we followed for the images. First, ask yourself about the category to which the main people, places, or things belong. Making a list may help you to classify more complex items:

- Monopolies and Mergers Commission

- Office of Fair Trading

- it (i.e., Office of Fair Trading again)

Note that the third item in the list–it–is a pronoun, a word that replaces a noun in order to avoid direct repetition. While pronouns do not repeat the word directly, they are nevertheless important for understanding the text that you are summarizing: pronouns show text-connecting relationships. The pronoun it gains its sense here from the antecedent Office of Fair Trading; the paragraph repeats an item without directly naming that item a second time.

As you did for the pineapple, grapes, and banana, you need to think of a collective word or phrase for the Monopolies and Mergers Commission and the Office of Fair Trading. You may come up with British governmental groups, the UK’s competition authorities, or even more generally the British government. Make this phrase your grammatical subject:

British governmental groups…

Again, you will need to state something about those organizations: what have they been doing or how are they similar? Look at their actions:

- decided…[superstores’ actions were] “beneficial to competition and to the consumer.”

- announced…it “was unable to identify any particular case which amounted to an abuse of buying power or other anti-competitive practice.”

- decided to take no action

You may have something like took no action against superstores’ retail practices, ruled in the favor of big grocery chain stores, or maintained that superstores were not monopolizing the food retail market. This action would be your verb and object (i.e., predicate).

British governmental groups took no action against superstores’ anti-competitive retail practices.

You may also wish to add adverbials (i.e., phrases that explain when, how, or why) to give a more nuanced sense of Monbiot’s overall claim in this paragraph:

In the 80s and 90s, British governmental groups took no action against superstores’ anti-competitive retail practices.

As several years have passed since Monbiot wrote this article, you may now know whether this governmental support has changed (or not); however, if you are relying on a specific source for this information (and you are here–Monbiot’s article), you summarize what is in that source without changing it. When you summarize, you are simply recognizing what the author has stated. So, the last step is to show your readers that this information is not yours by stating where you have obtained this information (we will discuss citations further below):

In the 80s and 90s, British governmental organizations took no action against superstores’ anti-competitive retail practices (Monbiot 2006).

This summary sentence (with the reference included) is eighteen words–about a sixth the length of the original paragraph. Of course, it does not have all of the details of the original, but it aims at retaining the essence and meaning of the original.

When you are summarizing even larger portions of text, the process is not that different, but you may need to group portions of text together yourself. While authors will sometimes group sections of text together for you through subheadings, you will still need to assess if there are further sub-groupings within those subheadings. Fortunately, such assessment is often easier than one might think: authors tend to put paragraphs about the same idea next to each other.

Let’s look at an example of two paragraphs from Nicholas Carr’s “How the Internet is Making Us Stupid” (2010):

In one experiment at a US university, half a class of students was allowed to use internet-connected laptops during a lecture, while the other had to keep their computers shut. Those who browsed the web performed much worse on a subsequent test of how well they retained the lecture’s content. Earlier experiments revealed that as the number of links in an online document goes up, reading comprehension falls, and as more types of information are placed on a screen, we remember less of what we see.

Studies of our behaviour online support this conclusion. German researchers found that web browsers usually spend less than 10 seconds looking at a page. Even people doing academic research online tend to “bounce” rapidly between different documents, rarely reading more than a page or two, according to a University College London study.

The process remains the same here across two paragraphs: you need to ask yourself who or what are the main people, places, or things in these two paragraphs. Make a list:

- US university

- German researchers

- University College London study

Once again, you will need a common term for these people or organizations. You might settle on researchers, scientists, or studies. What have those studies found?

- US university: 1) when browsing the web when receiving information, students performed more poorly on subsequent tests 2) more links in a document related to lower comprehension of that document 3) more types of information on screen related to lower retention

- German researchers/UCL study: readers bounce quickly when browsing the web

Note what is similar to those studies and state where you sourced your information:

Some studies have found that when people read on the web, they retain less information (Carr 2010).

Again, while later studies may have supplanted those which Carr discusses, your job in summarizing Carr’s article is just to report what Carr’s article shows. You can write a separate summary of (and cite) those later studies should they be pertinent to your argument or if you wish to show how our understanding of the topic is changing over time.

Here, we have seen one possible process for summary:

- Identify items or ideas of similarity that can be grouped together. The groupings may be within a paragraph or they may be across a series of paragraphs.

- Discover who or what are the main people, places, or things in that grouping.

- Find the action or the state common to those people, places, or things.

- Cite where you got the information.

- Faithfully transmit the essence of your source.

Genre (discussed below in 8.6) will further determine how you summarize.

8.3 Should You Summarize with AI Technology?

AI chatbots such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Microsoft’s CoPilot, or Google’s Gemini can indeed summarize verbal material. However, that ability does not necessarily mean that the summaries are as effective as a human can create. In order to assess the validity of an AI chatbot’s summary, you will need to read the source material and perhaps hone the summary to make it more effective. You can be assured of how effectively they summarize material only if you have indeed read the material and thought critically about the source’s meaning.

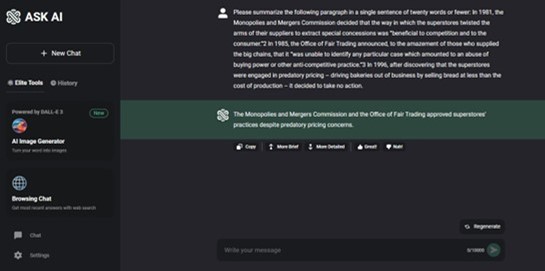

Let’s look at our Monbiot example from above (a 105-word paragraph which we condensed to an 18-word summary sentence) and see what AI does with it. When we enter the prompt “Please summarize the following paragraph in a single sentence of twenty words or fewer” and then provide the Monbiot paragraph, ChatGPT returns the following summary (see Figure 3):

The Monopolies and Mergers Commission and the Office of Fair Trading approved superstores’ practices despite predatory pricing concerns.

On the surface, this summary looks pretty similar to ours, but is it accurate: who has the predatory pricing concerns?

As many AI chatbots are quite responsive to prompts for improvements or changes in a response, we can use a follow-up prompt to ask the chatbot to clarify which people have concerns: “In the summary that you provided, could you please be clearer about who had predatory pricing concerns?” ChatGPT returned, “The Monopolies and Mergers Commission and the Office of Fair Trading approved superstores’ practices despite concerns about predatory pricing.”, which is a slight rewording of the last few words of its first summary, but not one that is much clearer about who has the concerns.

This lack of clarity might arise from the prompt, so it behooves us to reformulate prompts to see if we get different answers. To the follow-up prompt “Sorry, who has the concerns?”[1] ChatGPT returned, “Concerns about predatory pricing were raised by the Monopolies and Mergers Commission and the Office of Fair Trading.” While the initial summary that ChatGPT provided may have been vague on concerns, this final summary seems somewhat misleading: the point of Monbiot’s paragraph is mostly that the governmental agencies (at least in 1981 and 1985) didn’t have any concerns–but we wouldn’t recognize the potential inaccuracy here if we hadn’t already read the material.

AI chatbots are tools, and often very good ones at that. However, you can be assured of how effectively they summarize material only if you have indeed read the material.

8.4 To Summarize Effectively, You Must Read This

If you would like to summarize effectively (or have a chatbot help you to summarize material), you must read…the material carefully. And then read it again. And again. Fortunately, you can use some of the techniques that we have already discussed in previous chapters to help this reading (and re-reading!) process.

1) Skim

Start by skimming the whole article to get a general sense of it (see Chapter 7). Look at the title, subheadings, emphasized text, introduction, conclusion, and topic sentences. The title, introduction, and conclusion may give you a sense of the article’s overall argument, which will help if you are summarizing the whole article. The subheadings in an article and the topic sentences of its paragraphs may give you a sense of groupings that either support or nuance that overall argument.

2) Scan

After skimming, you may wish to scan the article for repeated words or phrases. When authors repeat words or phrases, those repetitions often signal concepts important to the overall argument or to any one section. While skimming will give you an initial overall sense of the article, scanning can help you determine if your your initial ‘take’ on the text is accurate or if it needs to be revised. Scanning can also help you group paragraphs together.

3) Re-read More Slowly and Annotate

Now that you have the gist of the article, re-read the article more slowly and fully, confirming or updating your understanding of the text. Annotate as you go, making notes in the margins and using brackets, arrows, or highlights to group sections of text together.

As Kirkland and Saunders (1991) have noted, summary writing requires considerable mental effort because of external and internal factors. External factors are often those beyond your control: the article that you are assigned to summarize; the people or groups for whom you are summarizing, the amount of time that you have to complete the assignment and how much that assignment is worth; and environmental factors (you might be trying to summarize in a noisy classroom, for example).

While you cannot necessarily control those external factors, you can mitigate them. You can read the source text several times to become more familiar with it. Approach the new article as you would approach someone whom you are meeting for the first time. Take quick stock of what you see (skim), then ask small-ish questions of it (scan it, confirming or rejecting your first impressions), and spend quality time with it (read it slowly) by taking it somewhere special: place yourself in a space where you can devote careful attention to it.

8.5 What You Read May Structure What You Write

One of the external factors that Kirkland and Saunders (1991) note is genre. Genre is a category or style of writing. You may, for example, read narrative, expository, or argumentative pieces at university. Identifying the style or category of writing will help you summarize effectively, particularly because different genres seem to present different challenges in summarizing (Hidi and Anderson 1986, Yu 2009, and Li 2014).

Narrative

If you are reading a narrative piece, there will likely be a main character(s)–a person or people whose story the narrative tells, whose names are frequently repeated, and who routinely act. This character will likely feature prominently in your summary, often as the grammatical subject of your sentences.

The general features of stories can help you structure what you will state about that main character. Stories typically have exposition (the information that you need to understand the characters and the story world), some sort of problem that intensifies or an obstacle that the main character(s) need to overcome, and a resolution (how the problem or obstacle is resolved). These main features might give structure as sentences or sections for your summary, as in the following summary for Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone:

In J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (1997), eleven-year-old Harry Potter begins his journey towards becoming one of our world’s most powerful wizards. Since his infancy, the orphaned Harry has been living with his neglectful aunt and uncle, who hide Harry from his magical past. When he moves to Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, he discovers that there are many other magical people and objects–such as the Philosopher’s Stone, which can ensure immortality–and that he must also protect the stone from those who will use it for evil. Because of Harry’s magical past, he is able to successfully protect the stone and survive his first year at Hogwarts.

The topic sentence of this summary gives a sense of the story as a whole–Harry’s initial foray into the world of wizardry. The second sentence provides Harry’s backstory and situates him in the story world (exposition): he is an orphan unaware that he has special powers. The third sentence recognizes the main problem that needs to be overcome (discovering and protecting the Philosopher’s Stone), and the fourth recognizes the resolution to that problem (Harry succeeds in safeguarding the stone). There are many other events that happen over the course of this 332-page book (Harry goes to Diagon Alley for the first time, gets sorted into his school house, becomes a Quidditch Seeker, etc.), but a summary of a narrative is interested in the broad view of the story. Note also that Harry (or a synonym for Harry) features as the grammatical subject of each sentence in the summary, keeping the focus clearly on the main character’s plight.

Expository Writing

Expository writing (writing that explains or describes) will not necessarily have a beginning, rising conflict, and resolution like many narratives do, but it may have more signaling devices to guide stages and potential causal, comparative, sequential, or spatial relationships. These signals often come in the form of structural or metadiscoursive markers, such as headers, sub-headers, or the numbering of steps. Take a moment to read Johanna Leggatt’s short article “What Is ChatGPT?”

The title suggests the article’s expository function; it will explain ChatGPT. The subheadings suggest how it will do so:

- What is ChatGPT?

- How does ChatGPT work?

- Other players in the AI race

- So, is ChatGPT any good?

- Pros of ChatGPT?

- Cons of ChatGPT?

To write a summary paragraph of this article, you could respond to those subsections with a sentence each. However, as we did earlier in this chapter, you may notice that some of those subheadings seem to cover similar ground. For example, the first and third subheadings point towards a similar idea: ChatGPT is one of many generative AI tools. The fourth subheading (So, is ChatGPT any good?) also seems to preview an argument of the piece (points five and six). In writing a summary, you can begin to group some of those similar concepts:

ChatGPT is one of many generative online tools that allow humans to ask questions and make requests in conversation with AI. ChatGPT is trained on enormous quantities of language, allowing it to replicate human speech patterns and converse as a virtual assistant. It is largely a reliable time-saving application that responds well to requests to refine what it produces, but it also has a relatively limited knowledge base, making it prone to errors and repetitive rhetoric and limiting its current usefulness (Leggatt 2023).

Note that the first sentence of this summary responds to the initial question (What is ChatGPT?) and therefore can act as a general topic sentence to the summary. The first sentence also uses that opportunity to contextualize that question in the third point (it is one of many large language model AI tools). The second sentence responds to the second subheading, and the third sentence groups the remaining three related subheadings.

We have used an expository example about ChatGPT to reiterate an earlier point: when you summarize a source, you report accurately that source’s position. Leggatt argues that ChatGPT was, in 2023, limited in its uses. As AI technology is changing rapidly, that position will likely change as well. However, you need to represent what that particular source reported, not what you believe to be true at the time you are writing the summary. If you would like to provide more up-to-date evidence or counter-evidence, you need to summarize that evidence accurately and cite it.

Argumentative Writing

Argumentative writing investigates a topic and takes a stance on that topic (i.e., it argues for one side of the issue or the other). An example of a short piece of argumentative writing is William Raspberry’s “Black–by Definition”, which we encourage you to read before continuing here.

Argumentative essays such as Raspberry’s will often state what topic they will explore and which side of the topic they are taking as a thesis statement. Thesis statements usually appear in introductions and are reiterated in conclusions–which is one of the reasons that we encourage you to skim those paragraphs before reading any article more fully. Raspberry’s second sentence provides his topic and argument: “one of the heaviest burdens black Americans and black children in particular have to bear is the handicap of definition: the question of what it means to be black.” His final sentence reiterates that argument: “What we seem to be doing, instead, is raising up yet another generation of young blacks who will be failures by definition.” A paraphrase or summary of this overall argument would make a good topic sentence if you were writing a summary paragraph of this article: “Black Americans are limited by America’s harmful racial binaries.”

Argumentative essays will try to support or prove their claims between their introductions and conclusions (i.e., the body of the essay), which Raspberry does through examples. As we did above, if authors do not structurally (e.g., by subheadings) or metadiscursively (e.g., using terms such as first, second, third, etc.) segment their supporting points for that argument, your job will be to recognize patterns. Let’s take a look at section of examples from “Black–by Definition”:

If a basketball fan says that the Boston Celtics’ Larry Bird plays “black,” the fan intends it–and Bird probably accepts it–as a compliment. Tell pop singer Tom Jones he moves “black,” and he might grin in appreciation. Say to Teena Marie or ‘The Average White Band’ that they sound “black,” and they’ll thank you.

As with the Monbiot example, you might decide to list the main characters and think of how you might group them:

- Larry Bird (NBA basketball player)

- Tom Jones (Welsh singer)

- Teena Marie (American singer)

While these people are all entertainers of some sort, you may choose to distinguish (as Raspberry does), classifying them as athletes and entertainers. Again, you will need to ascribe common actions or states to them:

- Play basketball “blackly”

- Dance “blackly”

- Sing “blackly”

All of those activities predominantly demonstrate physical, rather than intellectual, prowess. Indeed, one of Raspberry’s key points is that America defines physical talent as “black”, and intellectual abilities as “white”. Such groups of examples or subpoints will form the body of your summary.

Argumentative essays often make a conclusion about their topic. If you are writing a summary paragraph, you can use this conclusion to conclude your paragraph, giving your summary a similar shape to an argumentative essay itself: main argument as topic sentence; main sections of support for the argument as the body of your paragraph; and conclusion as the concluding sentence of your paragraph. That’s the shape that we have used here in our summary of Raspberry’s short essay:

Black Americans are limited by America’s harmful racial binaries. America often lauds intellectual excellence (such as good grades, communicating well, and perseverance) as “white”, but it defines physical talent (such as being good at sports and entertainment) as “black”. Americans will continue to suffer those binaries until their country promotes physical and intellectual success as being available to all individuals rather than innate to any one group of people (Raspberry 1982).

8.6 Out of Cite?

The academics who give you assignments are used to reading citation-laden research texts.[2] The academics who give you assignments are also probably used to creating citation-laden research texts. If you are doing a university assignment that has a research component, your instructors will expect to see citations in your assignment.

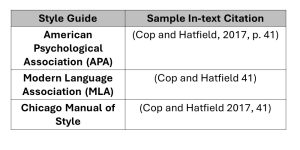

Within an academic context, there are numerous ways to cite your sources. Just as people in the same profession wear different clothes to distinguish themselves easily in a work setting (doctors might wear white coats, nurses may wear scrubs, etc.), different academic disciplines may have different citation styles. Using the correct format will identify you as someone who is part of that discourse community. To discover the appropriate citation style in your discipline, check your course outline or with your instructor.

Figure 4: Visuals Are Identifiers: Cite Using the Style of Your Discipline

If you use information from another source, you must cite that source. It doesn’t matter how you present that information–summary, paraphrase, or quotation–you must cite any information that you borrow.

The English Department uses the Chicago B citation style, a style that has some similarities with MLA and APA. Chicago B requires writers to have two parts to their citations: 1) a parenthetical citation in the body of the document and 2) a corresponding entry on the Reference List at the end of the document.

1) Parenthetical Citations

You must have a parenthetical citation (i.e., round brackets with information about the source) after the information that you have borrowed. In those round brackets, you will have at least two (but no more than three) pieces of information that will allow your reader to find the source on your Reference List:

- the last/family name of the author(s)

- the date that the article was published

- the relevant pages (if relevant or available)

The information should appear in that order: first, only the last/family name of the author(s); second, the date of publication (followed by a comma if you will have page numbers); and third, the relevant page numbers.

Earlier in this chapter, you saw the citations (Monbiot 2006) and (Carr 2010). They follow the order above. Those two citations have only the first two pieces of information because the articles were unpaginated.

In-text parenthetical citations follow the information but precede the full-stop:

In the 80s and 90s, British governmental organizations took no action against superstores’ anti-competitive retail practices (Monbiot 2006).

Some studies have found that when people read on the web, they retain less information (Carr 2010).

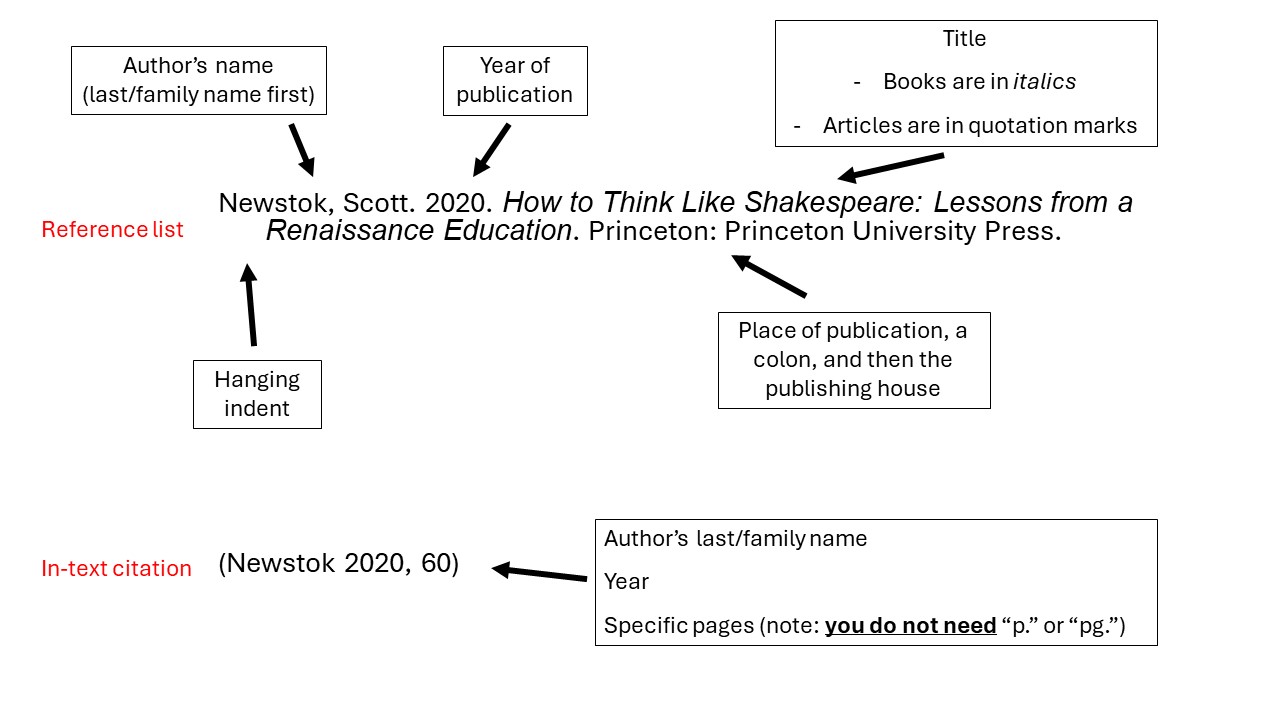

While those two examples are summaries, these rules are also true for paraphrases or quotations. For example, if you would like to quote “We can become more present to each other by sharing a common object for our focus” from page 60 of Scott Newstok’s book How to Think Like Shakespeare, you would introduce the quotation, place the quotation in quotation marks (“”), and provide whichever of the three pieces of information you haven’t already included in the sentence itself, as you can see in three different ways of presenting the same quotation:

Becoming more present does not need to be difficult: “We can become more present to each other by sharing a common object for our focus” (Newstok 2020, 60).

Newstok argues, “We can become more present to each other by sharing a common object for our focus” (2020, 60).

Newstok (2020) argues that “We can become more present to each other by sharing a common object for our focus” (60).

2) Reference List

The in-text citation is meant to help your readers find the fuller citation on your Reference List, which is why in-text citations provide the last/family name of the author(s) and the date of publication. There may be many Scotts in the world, but there will be fewer Newstoks, making the author easier to find. Your reference list is then organized alphabetically by authors’ last names to further aid readers’ search. Similarly, Newstok may have published many articles or books relevant to your research paper, but you are directing the reader towards one from a specific year. Within your reference list entries, the second piece of information is the year to help readers find the reference item easily based on the two pieces of information from your in-text citation.

There is, however, more information needed for each entry–information that would easily allow readers to find the book or article if they wanted to read it. The information needed for a basic book entry is:

- The name of the author(s): Scott Newstok

- The year of publication: 2020

- The title and subtitle of the book in italics (the latter follows a colon): How to Think Like Shakespeare: Lessons from a Renaissance Education

- The place of publication: Princeton

- The publisher: Princeton University Press

You organize the references as follows:

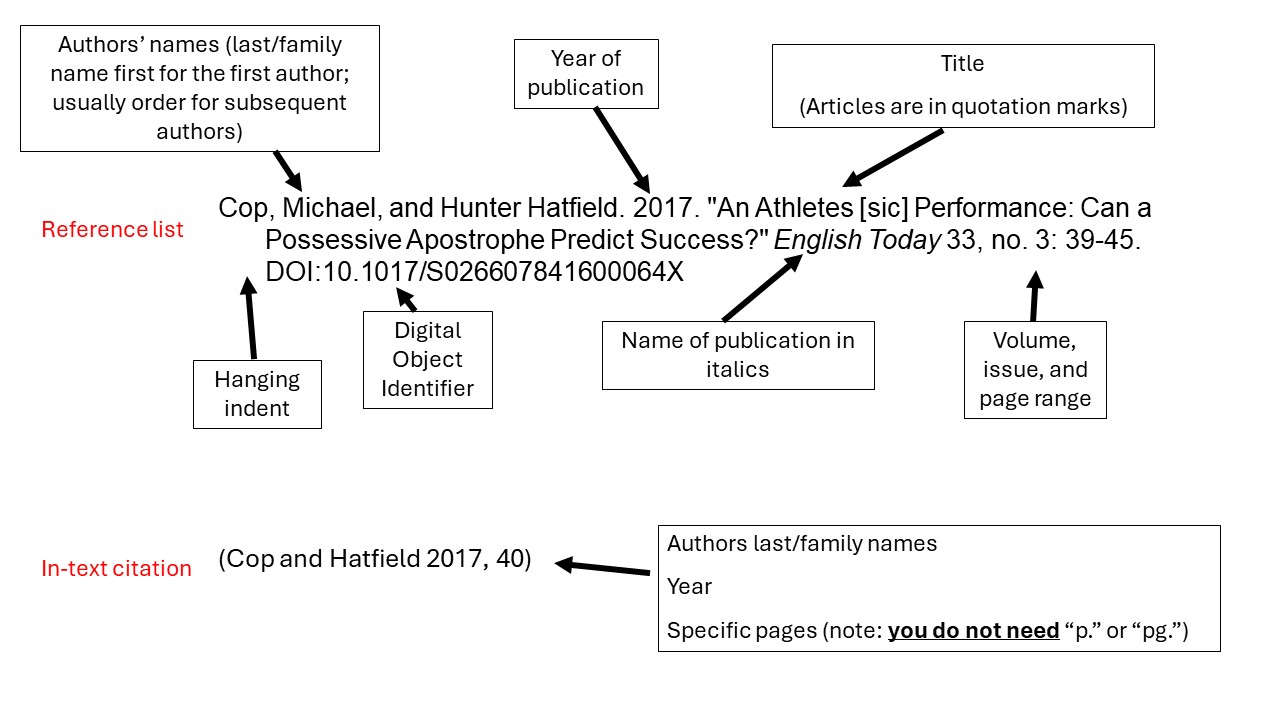

The information needed for an academic article entry is:

- The name of the author(s): Michael Cop and Hunter Hatfield (note that when there is more than one author, only the first author has his, her, or their family name first on the reference list)

- The year of publication: 2017

- The title of the article in quotation marks: “An Athletes [sic] Performance: Can a Possessive Apostrophe Predict Success?”

- The title of the journal in italics: English Today

- The volume and issue number of the publication: 33, no. 3

- The page range of the article: 39-45

- The durable URL or the DOI (Digital Object Identifier): DOI:10.1017/S026607841600064X

You organize the references as follows:

Works Cited

Booth, Wayne C., Gregory G. Colomb, Joseph M. Williams, Joseph Bizup, and William T. FitzGerald. 2016. The Craft of Research. 4th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Carr, Nicholas. 2010. “How the Internet Is Making Us Stupid.” The Telegraph. 27 August 2010. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/internet/7967894/How-the-Internet-is-making-us-stupid.html#.

The Chicago Manual of Style Online, 17th ed. 2017. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/cmos17

Cop, Michael, and Hunter Hatfield. “An Athletes [sic] Performance: Can a Possessive Apostrophe Predict Success?” English Today 33, no. 3: 39-45. DOI:10.1017/S026607841600064X

Hidi, Suzanne, and Valerie Anderson. 1986. “Producing Written Summaries: Task Demands, Cognitive Operations, and Implications for Instruction.” Review of Educational Research 56, no. 4: 473-493.

Kirkland, Margaret R., and Mary Anne P. Saunders. 1991. “Maximizing Student Performance in Summary Writing: Managing Cognitive Load.” Tesol Quarterly 25, no. 1: 105-121.

Leggatt, Johanna. 2023. “What Is ChatGPT? A Review Of The AI In Its Own Words.” Forbes. 22 March 2023. https://www.forbes.com/advisor/business/software/what-is-chatgpt/

Li, Jiuliang. 2014. “Examining Genre Effects on Test Takers’ Summary Writing Performance.” Assessing Writing 22: 75-90.

Monbiot, George. 2006. “Behold to the Mob.” 14 March 2006. https://www.monbiot.com/2006/03/14/beholden-to-the-mob/

Newstok, Scott. 2020. How to Think Like Shakespeare: Lessons from a Renaissance Education. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Raspberry, William. 1982. “Black–by Definition.” Washington Post. 6 January 1982. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1982/01/06/black-by-definition/386f6484-8f4c-4d13-9afd-535a44fdc189/

Rowling, J. K. 1997. Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. London: Bloomsbury.

Sword, Helen. 2012. Stylish Academic Writing. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Yu, Guoxing. 2009. “The Shifting Sands in the Effects of Source Text Summarizability on Summary Writing.” Assessing Writing 14, no. 2: 116-137.

Media Attributions

- Young people in conversation (Unsplash) © Alexis Brown is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Airquotes © Dronthego is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Fruit: a pineapple, a bunch of grapes and a banana © Banana by Justus Blümer (Pineapple and grapes are public domain by the US National Cancer Institute) adapted by Michael Cop is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Vehicles with broken windows © Car: Kafziel, Bus: Smiley.toerist, Train: Roger Carvell adapted by Michael Cop is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- ChatGPT’s Summary of the Monbiot Paragraph © Author screen shot is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Doctor with nurse cartoon © Videoplasty is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- An examples in three citation styles, APA, MLA and Chicago. © Michael Cop is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Book citations diagram © Michael Cop is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Article citations diagram © Michael Cop is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Note that pleasantries such as please and sorry do not seem to be necessary in prompts, but there is no harm in being polite to our soon-to-be AI overlords. ↵

- Note that even the brief Monbiot paragraph that we summarized had two citations in it. For variations in citation numbers per pages of articles among academic disciplines, see Helen Sword’s excellent 2012 book Stylish Academic Writing. ↵