Chapter 1: Overview of Interpersonal Communication

Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt

Tama and John have been friends since they were in preschool. They are both applying to the same university, hoping to be flat mates in their first year. Tama gets accepted, but John does not. Tama is crushed because he wanted to share his university experience with his best friend. John tells Tama to go without him, and he will try again next year after attending the local polytechnic for a semester. Tama is not as excited to go to university anymore because he is worried about John, and so he talks about different options with his whanau, and he discusses options with his online friends, too. This idea of sharing our experiences, whether it be positive or negative, mediated or face-to-face, is interpersonal communication. Interpersonal communication is when we offer information to other people and they offer information towards us.

Interpersonal Communication can be informal (the checkout line in a grocery store or a conversation at a friend’s flat) or formal (lecture classroom or job interview). It can be mediated (text, phone calls, social media platforms), but interpersonal communication often occurs in face-to-face contexts (unmediated). This type of interpersonal communication is often unplanned, spontaneous, and ungrammatical.

In this chapter, you will learn the concepts associated with different aspects of interpersonal communication and how certain variables can help you achieve your goals. You will learn about communication models that might influence how a message is sent and/or received. You will also learn about characteristics that influence the message and can cause others not to accept or understand the message that you were trying to send.

1.1 Purposes of Interpersonal Communication

Learning Objectives

- Explain Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and its relationship to communication

- Describe the relationship between self, others, and communication

Meeting Personal Needs

Communication fulfills our physical, personal, and social needs. Research has shown a powerful link between happiness and communication.1 In this particular study that included over 200 college students, they found that the ones who reported the highest levels of happiness also had a very active social life. They noted there were no differences between the happiest people and other similar peers in terms of how much they exercised, participated in religion, or engaged in other activities. The results from the study noted that having a social life can help people connect with others. We can connect with others through effective communication. Overall, communication is essential to our emotional wellbeing and perceptions about life. Research has shown that couples who engage in effective communication report more happiness than couples who do not,2 but communication is not an easy skill for everyone. As you read further, you will see that there are a lot of considerations and variables that can affect how a message is relayed and received.

Effective interpersonal communication is also important for our professional lives. For example, doctors, nurses, and other health professionals need to be able to listen to their patients to understand their concerns and medical issues. In turn, these health professionals have to be able to communicate the right type of treatment and procedures so that their patients will feel confident that it is the best type of outcome and they will comply with these medical orders.

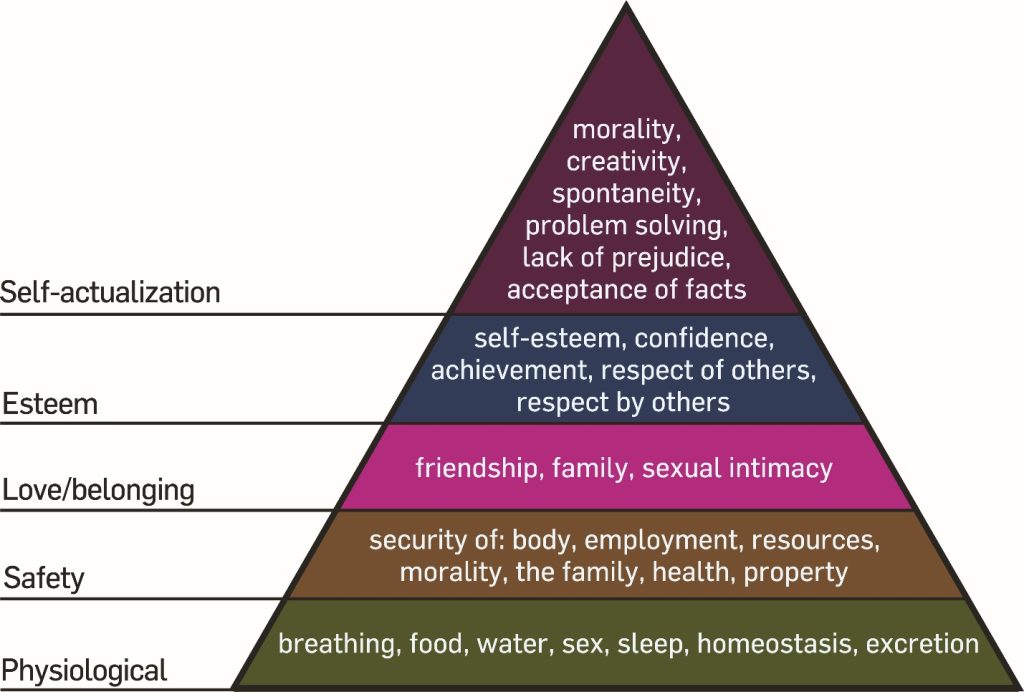

As Figure 1.1 indicates, psychologist Abraham Maslow (1908-1970) believed that human needs emerge in order starting from the bottom of the pyramid. At the basic level, humans must have physiological needs met, such as breathing, food, water, sex, homeostasis, sleep, and excretion. Once the physiological needs have been met, humans can attempt to meet safety needs, which include the safety of the body, family, resources, morality, health, and employment. A higher-order need that must be met is love and belonging, which encompasses friendship, sexual intimacy, and family. Another higher-order need that must be met before self-actualization is esteem, which includes self-esteem, confidence, achievement, respect of others, and respect by others. Maslow argued that all of the lower needs were necessary to help us achieve psychological health and eventually self-actualization.3 Self-actualization leads to creativity, morality, spontaneity, problem-solving, lack of prejudice, and acceptance of facts.

Communicating and Meeting Personal Needs

It is important to understand that people communicate to satisfy their needs, but each person’s need level is different. To survive, people need their physiological and safety needs to be met. Through communication, humans can work together to grow food, produce food, build shelter, create safe environments, and engage in protective behaviors. Once physiological and safety needs have been met, communication can then shift to love and belonging. Instead of focusing on survival, humans can focus on building relationships by discussing perhaps the value of a friendship or the desire for sexual intimacy. After creating a sense of love and belonging, humans can move forward to working on “esteem.” Communication may involve sharing praise, working toward goals, and discussion of strengths, which may lead to positive self-esteem. When esteem has been addressed and met, humans can achieve self-actualization. Communication will be about making life better, sharing innovative ideas, contributions to society, compassion and understanding, and providing insight to others. Imagine trying to communicate creatively about a novel or express compassion for others while starving and feeling unprotected. The problem of starving must be resolved before communication can shift to areas addressed within self-actualization.

Critics of Maslow’s theory argue that the hierarchy may not be absolute because it could be possible to achieve self-actualization without meeting the lower needs.4 For example, a parent/guardian might put before the needs of the child first if food is scarce. In this case, the need for food has not been fully met, yet the parent/guardian is able to engage in self-actualized behavior. Other critics point out that Maslow’s hierarchy is rather Western-centric and focused on more individualistic cultures (focus is on the individual needs and desires) and not applicable to cultures that are collectivistic (focus is on the family, group, or culture’s needs and desires).5

Other people may have different needs from us. This difference can influence how a message is received. Imagine the following scenario. Shaun and Dee have been dating for some time. Dee wants to talk about wedding plans and the possibility of having children. However, Shaun is struggling to make ends meet. He is focused on his paycheck, where he will get money to cover his rent, and what his next meal will be. Shaun finds it difficult to talk to Dee about their future plans when he is so focused on his basic physiological needs for food and water. Dee is on a different level, love and belonging, because she doesn’t have to worry about finances. In such a scenario, communication can be difficult when two people have very drastic needs that are not being met. Dee may feel like Shaun doesn’t love her because he refuses to talk about their future together. Shaun is upset with Dee because she doesn’t seem to understand how hard it is for him to deal with such a tight budget. If we are not able to understand to recognize that people may have different needs and identify where the other person’s needs are, then we might not be able to have connective conversations. Needs may factor into the context of interpersonal communication (or in other places in communication models), which is one of the factors in interpersonal communication models, as we shall now see.

1.2 Elements of Interpersonal Communication

Learning Objectives

- Understand that communication is a process.

- Differentiate among the components of communication processes and communication models.

- Describe the differences between the sender and receiver of a message.

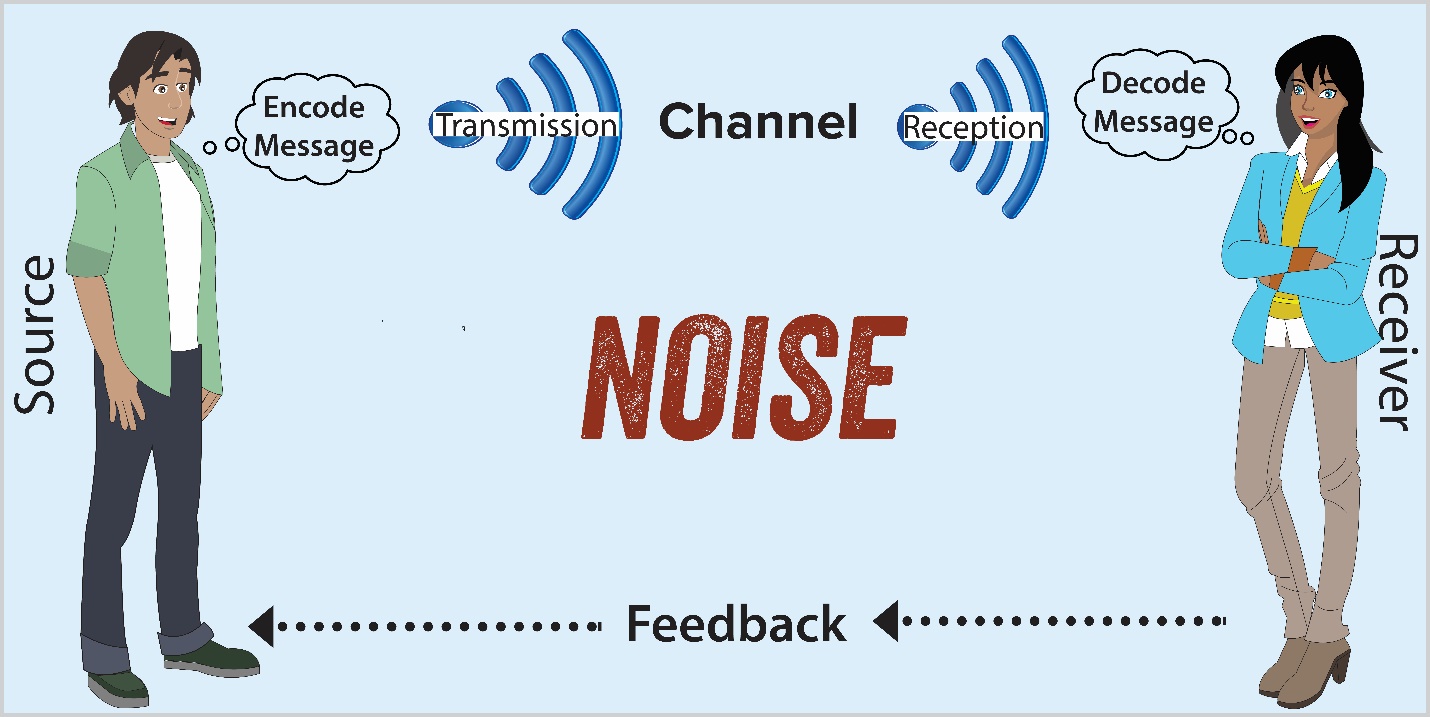

You may think that communication is easy. However, at moments in your life, communication might be hard and difficult to understand. We can study communication similar to the way we study other systems. There are elements to the communication process that are important to understand. Each interaction that we have will typically include a sender, receiver, message, channel, feedback, and noise. Let’s take a closer look at each one.

Sender

Humans encode messages naturally, and we don’t often consider this part of the process. However, if you have ever thought about the exact words that you would use to get a later curfew from your parents/guardians and how you might refute any counterpoints, then you intuitively know that choosing the right words – “encoding” – weighed heavily in your ability to influence your parents/guardians successfully. The language you chose mattered.

The sender is the encoder or source of the message. The sender is the person who decides to communicate and the intent of the message. The source may decide to send messages to entertain, persuade, inform, include, or escape. Often, the sources will create a message based on their feelings, thoughts, perceptions, and past experiences. For instance, if you have feelings of affection towards someone but never communicate those feelings toward that person, they will never know. The sender can withhold or release information.

Receiver

The transactional model of communication teaches us that we are both the sender and receiver simultaneously. The receiver(s) is the individual who decodes the message and tries to understand the source of the message. Receivers have to filter messages based on their attitudes, beliefs, opinions, values, history, and prejudices. People will encode messages through their five senses. We have to pay attention to the source of the message to receive the message. If the receiver does not get the message, then communication did not occur. The receiver needs to obtain a message.

Daily, you will receive several messages. Some of these messages are intentional, and some of these messages will be unintentional. For instance, a person waving in your direction might be waving to someone behind you, but you accidentally think they are waving at you. Some messages will be easy to understand, and some messages will be hard to interpret. Every time a person sends a message, they are also receiving messages simultaneously.

Message

Messages include any type of textual, verbal, and nonverbal aspects of communication, in which individuals give meaning. People send messages intentionally (texting a friend to meet for coffee) or unintentionally (accidentally falling asleep during lectures). Messages can be verbal (saying hello to your parents/guardians), nonverbal (hugging your parents/guardians), or text (words on a computer screen). Essentially, communication is how messages create meaning. Yet, meanings differ among people. For instance, a friend of yours promises to repay you for the money they borrowed, and they say “sorry” for not having any money to give you. You might think they were insincere, but another person might think that it was a genuine apology. People can vary in their interpretations of messages.

Channel

With advances in technology, cell phones act as many different channels of communication at once. Consider that smartphones allow us to talk and text. Also, we can receive communication through Facebook, Twitter, Email, Instagram, Snapchat, and Reddit. All of these channels are in addition to our longer-standing channels, which were face-to-face communication, letter writing, telegram, and the telephone. The addition of these new communication channels has changed our lives forever. The channel is the medium in which we communicate our message. Think about breaking up a romantic relationship. Would you rather do it via face-to-face or via a text message? Why did you answer the way that you did?

It may seem like a silly thing to talk about channels, but a channel can make an impact on how people receive the message, and some channels themselves might contribute to the meaning of the message. The channel can affect the way that a receiver reacts and responds to your message. For instance, a handwritten love letter might seem more romantic than a typed email for a variety of reasons: the paper has been in the other’s hand whereas an email is an electronic transmission; handwriting is unique to an individual whereas fonts are standardized; mailing a letter is a more effortful process (sourcing a paper, pen, envelope, and stamp, walking to find a mailbox, etc.); and so on. On the other hand, if there was some tragic news about your family, you would probably want someone to call you immediately rather than sending you a letter. The same process of letter writing may seem less mindful of the urgency of the message.

Overall, people naturally know that the message impacts which channel they might use. In a research study focused on channels, college students were asked about the best channels for delivering messages.6 College students said that they would communicate face-to-face if the message was positive, but use mediated channels if the message was negative.

Feedback

Feedback is the response to the message. If there is no feedback, interpersonal communication would be less effective. Feedback is important because the sender needs to know if the receiver got the message. Simultaneously, the receiver usually will give the sender some sort of message that they comprehend what has been said. Negative feedback is when there is no feedback or if it seems that the receiver did not understand the message. Positive feedback is when the receiver understood the message. Positive feedback does not mean that the receiver entirely agrees with the sender of the message, but rather the message was comprehended. Sometimes feedback is not positive or negative; it can be ambiguous. Examples of ambiguous feedback might include saying “hmmm” or “interesting” (be careful, though, because these can also be examples of active listening, discussed in subsequent chapters). Based on these responses, it is not clear if the receiver of the message understood part or the entire message. It is important to note that feedback doesn’t have to come from other people. Sometimes, we can be critical of our own words when we write them in a text or say them out loud. We might correct our words and change how we communicate based on our internal feedback.

Environment

The context or situation where communication occurs and affects the experience is referred to as the environment. We know that the way you communicate in a professional context might be different than in a personal context. In other words, you probably won’t talk to your boss the same way you would talk to your best friend. (An exception might be if your best friend was also your boss.) The environment will affect how you communicate. For instance, in a library, you might talk more quietly than normal so that you don’t disturb other library patrons. However, in a nightclub or bar, you might speak louder than normal due to the other people talking, music, or noise. Hence, the environment makes a difference in the way in which you communicate with others.

It is also important to note that environments can be related to fields of experience or a person’s past experiences or background. For instance, a town hall meeting that plans to cut primary access to lower socioeconomic residents might be perceived differently by individuals who use these services and those who do not. Environments might overlap, but sometimes they do not. Some people in university have had many family members who attended the same school, but other people do not have any family members that ever attended university.

Noise

Anything that interferes with the message is called noise. Noise keeps the message from being completely understood by the receiver. If noise is absent, then the message would be accurate. However, usually, noise impacts the message in some way. Noise might be physical (e.g., television, cell phone, fan, etc.), or it might be psychological (e.g., thinking about your parents/guardians or missing someone you love). Noise is anything that hinders or distorts the message.

There are four types of noise. The first type is physical noise. This is noise that comes from a physical object. For instance, people talking, birds chirping, a jackhammer pounding concrete, a car revving by, are all different types of physical noise.

The second type of noise is psychological noise. This is the noise that no one else can see for you unless they can read your mind. It is the noise that occurs in a person’s mind, such as frustration, anger, happiness, or depression. When you talk to a person, they might act and behave like nothing is wrong, but deep inside their mind, they might be dealing with a lot of other issues or problems. Hence, psychological noise is difficult to see or understand because it happens in the other person’s mind.

The third type of noise is semantic noise, which deals with language. This could refer to jargon, accents, or language use. Sometimes our messages are not understood by others because of the word choice. For instance, if a person used the word “lit,” it would probably depend on the other words accompanying the word “lit” and or the context. To say that “this party is lit” would mean something different compared to “he lit a cigarette.” If you were coming from another country, that word might mean something different. Hence, sometimes language-related problems, where the receiver can’t understand the message, are referred to as semantic noise.

The fourth and last type of noise is called physiological noise. This type of noise is because the receiver’s body interferes or hinders the acceptance of a message. For instance, if the person is blind, they are unable to see any written messages that you might send. If the person is deaf, then they are unable to hear any spoken messages. If the person is very hungry, then they might pay more attention to their hunger than any other message.

Mindfulness Activity

We live in a world where there is constant noise. Practice being mindful of sound. Find a secluded spot and just close your eyes. Focus on the sounds around you. Do you notice certain sounds more than others? Why? Is it because you place more importance on those sounds compared to other sounds?

Sounds can be helpful to your application of mindfulness.7 Some people prefer paying attention to sounds rather than their breath when meditating. The purpose of this activity is to see if you can discern some sounds more than others. Some people might find these sounds noisy and very distracting. Others might find the sounds calming and relaxing. There will be many times in life where you will be distracted because you might be overwhelmed with all the noise. It is essential to take a few minutes, just to be mindful of the noise and how you can deal with all the distractions. Once you are aware of the things that trigger these distractions or noise, then you will be able to be more focused and to be a better communicator.

Key Takeaways

- Communication is a process because senders and receivers act as senders and receivers simultaneously, with the receiver’s feedback serving as a key element to continuing the process.

- The components of the communication process involve the source, sender, channel, message, environment, and noise.

Exercises

- Think of your most recent communication with another individual. Write down this conversation and, within the conversation, identify the components of the communication process.

- Think about the different types of noise that affect communication. Can you list some examples of how noise can make communication worse?

- Think about the advantages and disadvantages of different channels. Write down the pros and cons of the different channels of communication.

1.3 Perception Process

Learning Objectives

- Describe perception and aspects of interpersonal perception.

- List and explain the three stages of the perception process.

- Understand the relationship between interpersonal communication and perception.

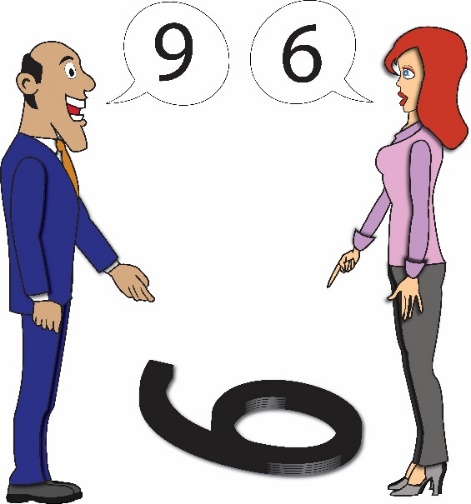

As you can see from Figure 1.2, how you view something is also how you will describe and define it. Your perception of something will determine how you feel about it and how you will communicate about it. In the figure, do you see it as a six or a nine? Why did you answer the way that you did?

Your perceptions affect who you are, and they are based on your experiences and preferences. If you have a horrible experience with a restaurant, you probably won’t go to that restaurant in the future. You might even tell others not to go to that restaurant based on your personal experience. Thus, it is crucial to understand how perceptions can influence others.

Sometimes the silliest arguments occur with others because we don’t understand their perceptions of things. Just like the figure shows, it is important to attempt to understand how the other person see things. In other words, put yourself in their shoes and see it from their perspective before jumping to conclusions or getting upset. That person might have a legitimate reason why they are not willing to concede with you.

Perception

Many of our problems in the world occur due to perception, or the process of acquiring, interpreting, and organizing information that comes in through your five senses. When we don’t get all the facts, it is hard to make a concrete decision. We have to rely on our perceptions to understand the situation. In this section, you will learn tools that can help you understand perceptions and improve your communication skills. As you will see in many of the illustrations on perception, people can see different things. In some of the pictures, some might only be able to see one picture, but there might be others who can see both images, and a small amount might be able to see something completely different from the rest of the class.

Many famous artists over the years have played with people’s perceptions. Figure 1.3 is an example of three artists’ use of twisted perceptions. The first picture was initially created by Danish psychologist Edgar Rubin and is commonly called The Rubin Vase. Essentially, you have what appears to either be a vase (the white part) or two people looking at each other (the black part). This simple image can be both images and neither image at the same time. The second work of art is Charles Allan Gilbert’s (1892) painting “All is Vanity.” In this painting, you can see a woman sitting in a chair with her back to the viewer, staring at herself in a round mirror so that the viewer sees her reflection in that mirror. At the same time, the image is also a giant skull, where that round mirror forms the outline of the top of the skull and the tablecloth forms the jawline. Lastly, we have William Ely Hill (1915) “My Wife and My Mother-in-Law,” which may have been loosely based on an 1888 German postcard. In Hill’s painting, you have two different images, one of a young woman and one of an older woman: the young woman turns away from the viewer so that her partial profile is visible to the viewer; that same jawline forms the nose of the older woman who is much larger and in full profile. These visual images are helpful reminders that we don’t always perceive things in the same way as those around us do. There are often multiple ways to view and understand the same set of events.

When it comes to interpersonal communication, each time you communicate to other people, you make choices. Sometimes you represent yourself more fully or accurately, and other times you may present an edited version of yourself; people may perceive those presentations in ways that we might not have anticipated. Other people can also present themselves how they want others to see them. For example, influencers might present themselves positively on social media in ways that foster strong relationships in the digital realm or have positive financial outcomes. Then, their followers or fans get shocked to learn when those presentations might not match with what happens outside of the digital realm. In this section, we will learn that the perception process has three stages: attending, organizing, and interpreting.

Attending

The first step of the perception process is to select what information you want to pay attention to or focus on, which is called attending. You will pay attention to things based on how they look, feel, smell, touch, and taste. At every moment, you are obtaining a large amount of information. So, how do you decide what you want to pay attention to and what you choose to ignore? People will tend to pay attention to things that matter to them. Usually, we pay attention to things that are louder, larger, different, and more complex to what we ordinarily view.

When we focus on a particular thing and ignore other elements, we call it selective perception. For instance, when you are in love, you might pay attention to only that special someone and not notice anything else. The same thing happens when we end a relationship, and we are devasted; we might see how everyone else is in a great relationship, but we aren’t.

There are a couple of reasons why you pay attention to certain things more so than others.

The first reason why we pay attention to something is because it is extreme or intense. In other words, it stands out of the crowd and captures our attention, like an extremely good looking person at a party or a big neon sign in a dark, isolated town. We can’t help but notice these things because they are exceptional or extraordinary in some way.

Second, we will pay attention to things that are different or contradicting. Commonly, when people enter an elevator, they face the doors. Imagine if someone entered the elevator and stood with their back to the elevator doors staring at you. You might pay attention to this person more than others because the behavior is unusual. It is something that you don’t expect, and that makes it stand out more to you. “Different” could also be something that you are not used to or something that no longer exists for you. For instance, if you had someone very close to you pass away, then you might pay more attention to the loss of that person than to anything else. Some people grieve for an extended period because they were so used to having that person around, and things can be different since you don’t have them to rely on or ask for input.

The third thing that we pay attention to is something that repeats over and over again. Think of a catchy song or a commercial that continually repeats itself. We might be more alert to it since it repeats, compared to something that was only said once. When we discuss effective oral presentations, we will consider how important repetition is in solidifying concepts for an audience and in emphasizing your key points.

The fourth thing that we will pay attention to is based on our motives. If we have a motive to find a romantic partner, we might be more perceptive to other attractive people than normal, because we are looking for romantic interests. Another motive might be to lose weight, and you might pay more attention to exercise advertisements and food selection choices compared to someone who doesn’t have the motive to lose weight. Our motives influence what we pay attention to and what we ignore.

The last thing that influences our selection process is our emotional state. If we are in an angry mood, then we might be more attentive to things that get us angrier. If we are in a happy mood, then we will be more likely to overlook a lot of negativity because we are already happy. Selecting doesn’t involve just paying attention to certain cues. It also means that you might be overlooking other things. For instance, people in love will think their partner is amazing and will overlook a lot of their flaws. We are so focused on how wonderful they are that we often will neglect the other negative aspects of their behavior.

Organizing

Look again at the three images in Figure 1.3. What were the first things that you saw when you looked at each picture? Could you see the two different images? Which image was more prominent? When we examine a picture or image, we engage in organizing it in our head to make sense of it and define it. This is an example of organization. After we select the information to which we are paying attention, we have to make sense of it. This stage of the perception process is referred to as organization, and information can be organized in different ways. After we attend to something, our brains quickly want to make sense of this data–hence why you may have prioritized one image in the figures above the others.

There are four types of schemes that people use to organize perceptions.8 First, physical constructs are used to classify people (e.g., young/old; tall/short; big/small). Second, role constructs are social positions (e.g., mother, friend, lover, doctor, teacher). Third, interaction constructs are the social behaviors displayed in the interaction (e.g., aggressive, friendly, dismissive, indifferent). Fourth, psychological constructs are the dispositions, emotions, and internal states of mind of the communicators (e.g., depressed, confident, happy, insecure). We often use these schemes to better understand and organize the information that we have received. We use these schemes to generalize others and to classify information.

Let’s pretend that you came to class and noticed that one of your classmates was wildly waving their arms in the air at you. This behavior will most likely catch your attention because you find this behavior strange. Then, you will try to organize or makes sense of what is happening. Once you have organized it in your brain, you will need to interpret the behavior.

Interpreting

The final stage of the perception process is interpreting. In this stage of perception, you are attaching meaning to understand the data. So, after you select information and organize things in your brain, you have to interpret the situation. As previously discussed in the above example, your friend waves their hands wildly (attending), and you are trying to figure out what they are communicating to you (organizing). You will attach meaning (interpreting). Does your friend need help and is your friend trying to get your attention, or does your friend want you to watch out for something behind you?

We interpret other people’s behavior daily. Walking to class, you might see an attractive stranger smiling at you. You could interpret this as a flirtatious behavior or someone just trying to be friendly. There are a variety of factors that influence our interpretations:9

Personal Experience

First, personal experience impacts our interpretation of events. What prior experiences have you had that affect your perceptions? Maybe you heard from your friends that a particular restaurant was really good, but when you went there, you had a horrible experience, and you decided you never wanted to go there again. Even though your friends might try to persuade you to try it again, you might be inclined not to go, because your past experience with that restaurant was not good. Another example might be a traumatic relationship break up. You might have had a relational partner that cheated on you and left you with trust issues. You might find another romantic interest, but in the back of your mind, you might be cautious and interpret loving behaviors differently, because you don’t want to be hurt again.

Involvement

Second, the degree of involvement impacts your interpretation. The more involved or deeper your relationship is with another person, the more likely you will interpret their behaviors differently compared to someone you do not know well. For instance, let’s pretend that you are a manager, and two of your employees come to work late. One worker just happens to be your best friend and the other person is someone who just started and you do not know them well. You are more likely to interpret your best friend’s behavior more altruistically than the other worker because you have known your best friend for a longer period. Besides, since this person is your best friend, you likely interact and are more involved with them compared to other friends.

Expectations

Third, the expectations that we hold can impact the way we make sense of other people’s behaviors. For instance, if you overheard some friends talking about a mean professor and how hostile they are in class, you might be expecting this characterization to be true. Let’s say you meet the professor and attend their class; you might still have certain expectations about them based on what you heard. Even those expectations might be completely false, and you might still be expecting those allegations to be true.

Assumptions

Fourth, there are assumptions about human behavior. Imagine if you are a personal fitness trainer, do you believe that people like to exercise or need to exercise? Your answer to that question might be based on your assumptions. If you are a person who is inclined to exercise, then you might think that all people like to work out. However, if you do not like to exercise but know that people should be physically fit, then you would more likely agree with the statement that people need to exercise. Your assumptions about humans can shape the way that you interpret their behavior. Another example might be that if you believe that most people would donate to a worthy cause, you might be shocked to learn that not everyone thinks this way. When we assume that all humans should act a certain way, we are more likely to interpret their behavior differently if they do not respond in a certain way.

Relational Satisfaction

Fifth, relational satisfaction will make you see things very differently. Relational satisfaction is how satisfied or happy you are with your current relationship. If you are content, then you are more likely to view all your partner’s behaviors as thoughtful and kind. However, if you are not satisfied in your relationship, then you are more likely to view their behavior has distrustful or insincere. Research has shown that unhappy couples are more likely to blame their partners when things go wrong compared to happy couples.10

Conclusion

In this section, we have discussed the three stages of perception: attending, organizing, and interpreting. Each of these stages can occur out of sequence. For example, if your parent/guardian had a bad experience at a car dealership based on their interpretation (such as “They overcharged me for the car and they added all these hidden fees.”), then it can influence their future selection (looking for credible and highly rated car dealerships), and then your parent/guardian can organize the information (car dealers are just trying to make money, the assumption is that they think most customers don’t know a lot about cars). Perception is a continuous process, and it is very hard to determine the start and finish of any perceptual differences.

Key Takeaways

- Perception involves attending, organizing, and interpreting.

- Perception impacts communication.

- Attending, organizing, and interpreting have specific definitions, and each is impacted by multiple variables.

Exercises

- Take a walk to a place you usually go to on campus or in your neighborhood. Before taking your walk, mentally list everything that you will see on your walk. As you walk, notice everything on your path. What new things do you notice now that you are deliberately “attending” to your environment?

- What affects your perception?

- Look back at a previous text or email that you got from a friend. After reading it, do you have a different interpretation of it now compared to when you first got it? Why? Think about how interpretation can impact communication if you didn’t know this person. How does it differ?

1.4 Models of Interpersonal Communication

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate among and describe the various action models of interpersonal communication

- Differentiate among and describe the various interactional models of interpersonal communication

- Differentiate among and describe the various transactional models of interpersonal communication

We have several different models to help us understand what communication is and how it works. A model is a simplified representation of a system (often graphic) that highlights the crucial components and connections of concepts, which are used to help people understand an aspect of the real-world. For our purposes, the models have all been created to help us understand how real-world communication interactions occur. The goal of creating models is three-fold:

- to facilitate understanding by eliminating unnecessary components,

- to aid in decision making by simulating “what if” scenarios, and

- to explain, control, and predict events on the basis of past observations.11

The next few paragraphs will examine three different types of models that communication scholars have proposed to help us understand interpersonal interactions: action, interactional, and transactional.

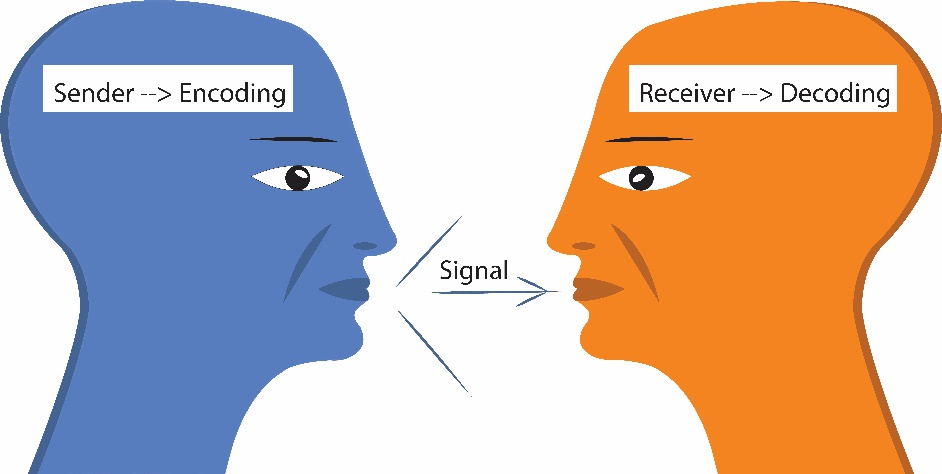

Action Models

The purpose of using models is to provide visual representations of interpersonal communication and to offer a better understanding of how various scholars have conceptualized it over time. The first type of model we’ll be exploring are action models, or communication models that view communication as a one-directional transmission of information from a source or sender to some destination or receiver.

Shannon-Weaver Model

Shannon and Weaver were both engineers for the Bell Telephone Labs. Their job was to make sure that all the telephone cables and radio waves were operating at full capacity. They developed the Shannon-Weaver model, which is also known as the linear communication model (Weaver & Shannon, 1963).12 As indicated by its name, the scholars believed that communication occurred in a linear fashion, where a sender encodes a message through a channel to a receiver, who will decode the message. Feedback is not immediate. Examples of linear communication were newspapers, radio, and television.

Early Schramm Model

The Shannon-Weaver model was criticized because it assumed that communication always occurred linearly. Wilbur Schram (1954) felt that it was important to notice the impact of messages.13 Schramm’s model regards communication as a process between an encoder and a decoder. Most importantly, this model accounts for how people interpret the message. Schramm argued that a person’s background, experience, and knowledge are factors that impact interpretation. Besides, Schramm believed that the messages are transmitted through a medium. Also, the decoder will be able to send feedback about the message to indicate that the message has been received. He argued that communication is incomplete unless there is feedback from the receiver. According to Schramm’s model, encoding and decoding are vital to effective communication. Any communication where decoding does not occur or feedback does not happen is not effective or complete.

Berlo’s SMCR Model

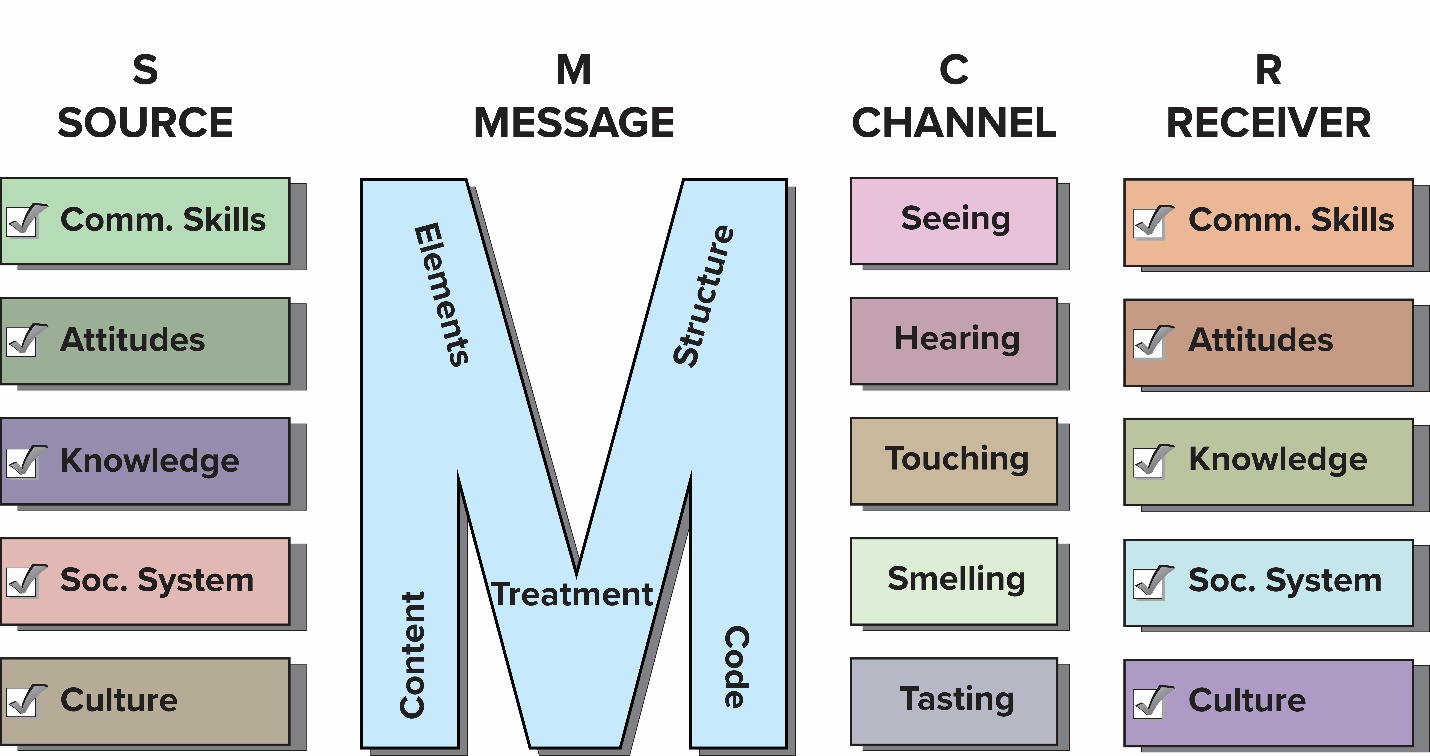

David K. Berlo (1960)14 created the SMCR model of communication. SMCR stands for sender, message, channel, receiver. Berlo’s model describes different components of the communication process. He argued that there are three main parts of all communication, which is the speaker, the subject, and the listener. He maintained that the listener determines the meaning of any message.

In regards to the source or sender of the message, Berlo identified factors that influence the source of the message. First, communication skills refer to the ability to speak or write. Second, attitude is the person’s point-of-view, which may be influenced by the listener. The third is whether the source has requisite knowledge on a given topic to be effective. Fourth, social systems include the source’s values, beliefs, and opinions, which may influence the message.

Next, we move onto the message portion of the model. The message can be sent in a variety of ways, such as text, video, speech. At the same time, there might be components that influence the message, such as content, which is the information being sent. Elements refer to the verbal and nonverbal behaviors of how the message is sent. Treatment refers to how the message was presented. The structure is how the message was organized. Code is the form in which the message was sent, such as text, gesture, or music.

The channel of the message relies on the basic five senses of sound, sight, touch, smell, and taste. Think of how your mother might express her love for you. She might hug you (touch) and say, “I love you” (sound), or make you your favorite dessert (taste). Each of these channels is a way to display affection.

The receiver is the person who decodes the message. Similar to the models discussed earlier, the receiver is at the end. However, Berlo argued that for the receiver to understand and comprehend the message, there must be similar factors to the sender. Hence, the source and the receiver have similar components. In the end, the receiver will have to decode the message and determine its meaning. Berlo tries to present the model of communication as simple as possible. His model accounts for variables that will obstruct the interpretation of the model.

Interaction Models

Interaction models view the sender and the receiver as responsible for the effectiveness of the communication. One of the biggest differences between the action and interaction models is a heightened focus on feedback.

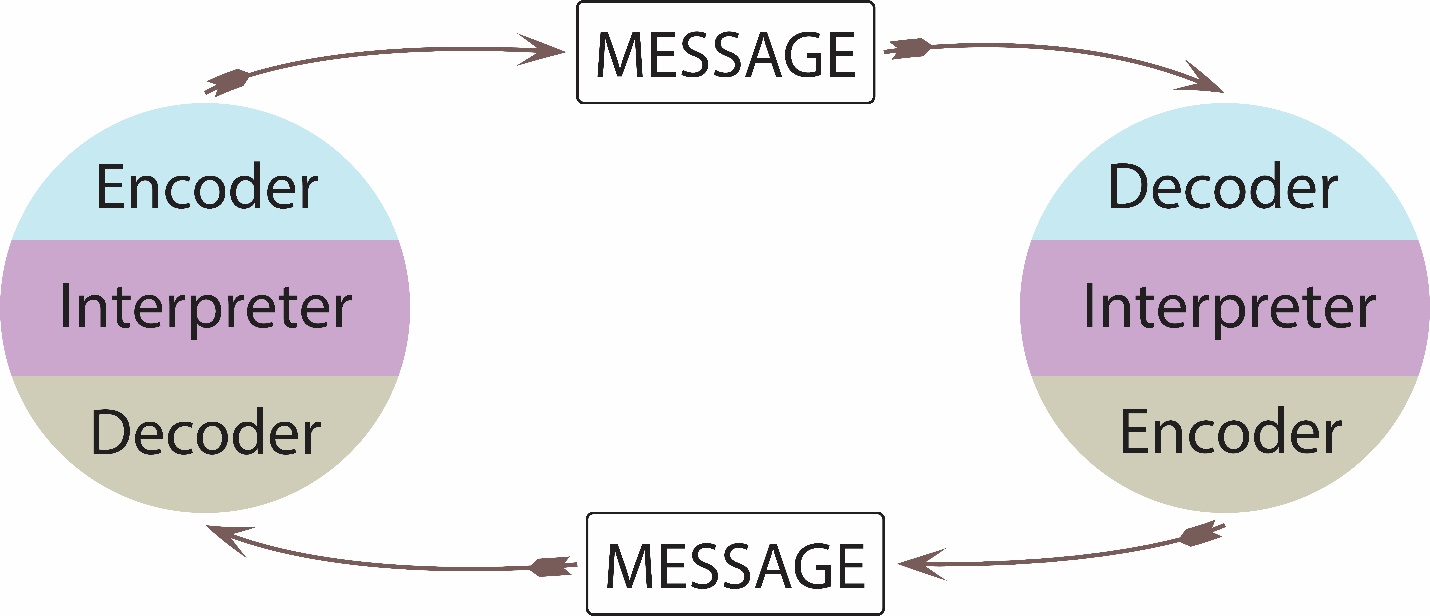

Osgood and Schramm Model

Osgood-Schramm’s model of communication is known as a circular model because it indicates that messages can go in two directions.15 Hence, once a person decodes a message, they can encode it and send a message back to the sender. They could continue encoding and decoding into a continuous cycle. This revised model indicates that: 1) communication is not linear, but circular; 2) communication is reciprocal and equal; 3) messages are based on interpretation; 4) communication involves encoding, decoding, and interpreting. The benefit of this model is that the model illustrates that feedback is cyclical. It also shows that communication is complex because it accounts for interpretation. This model also showcases the fact that we are active communicators, and we are active in interpreting the messages that we receive.

Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson Model

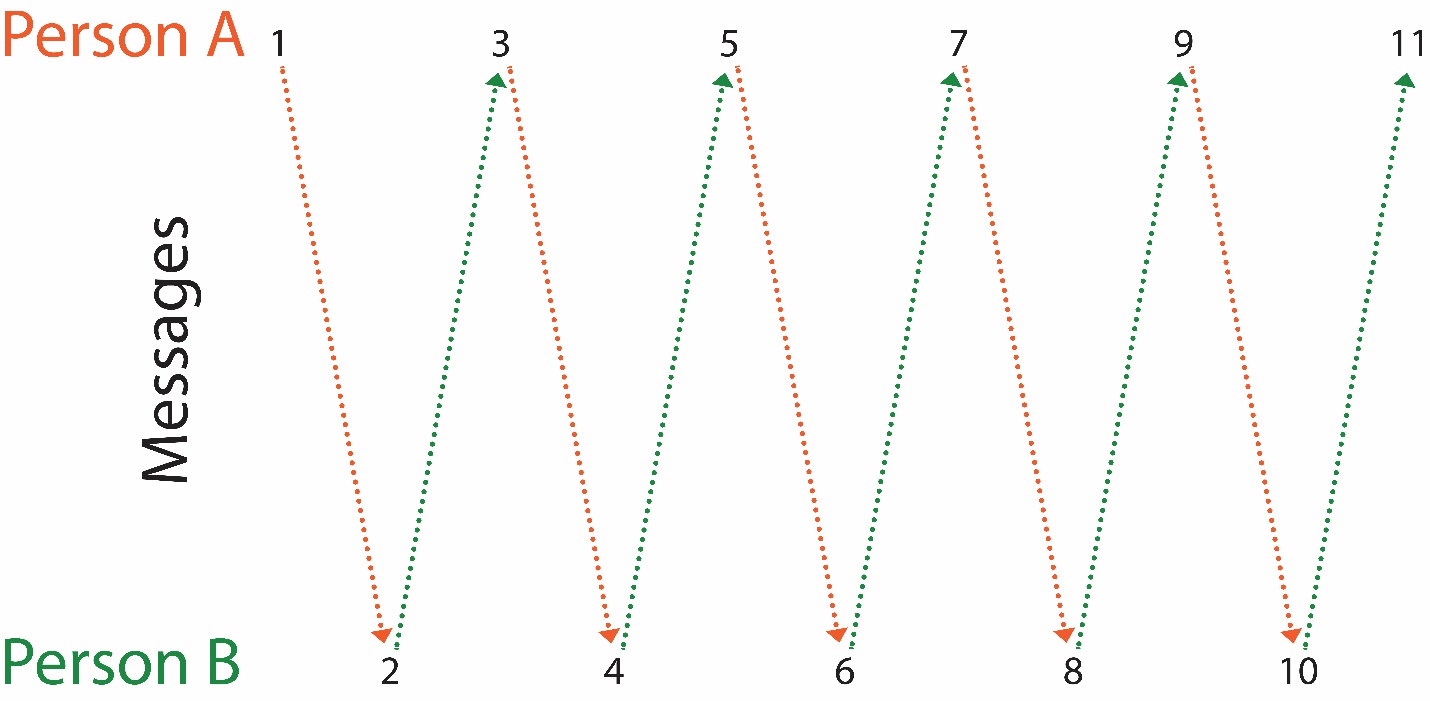

Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson argued that communication is continuous.16 The researchers argued that communication happens all the time. Every time a message is sent, a message is returned, and it continues from Person A to Person B until someone stops. Feedback is provided every time that Person A sends a message. With this model, there are five axioms.

First, one cannot not communicate. This dynamic means that everything one does has communicative value. Even if people do not talk to each other, then this lack of talking still communicates the idea that both parties do not want to talk to each other. The second axiom states that every message has a content and relationship dimension. Content is the informational part of the message or the subject of discussion. The relationship dimension refers to how the two communicators feel about each other. The third axiom is how the communicators in the system punctuate their communicative sequence. The scholars observed that every communication event has a stimulus, response, and reinforcement. Each communicator can be a stimulus or a response. Fourth, communication can be analog or digital. Digital refers to what the words mean. Analogical is how the words are said or the nonverbal behavior that accompanies the message. The last axiom states that communication can be either symmetrical or complementary. This binary means that both communicators have similar power relations, or they do not. Conflict and misunderstandings can occur if the communicators have different power relations. For instance, your boss might have the right to fire you from your job if you do not professionally conduct yourself.

Transaction Models

The transactional models differ from the interactional models in that the transactional models demonstrate that individuals are often acting as both the sender and receiver simultaneously. Sending and receiving messages happen simultaneously.

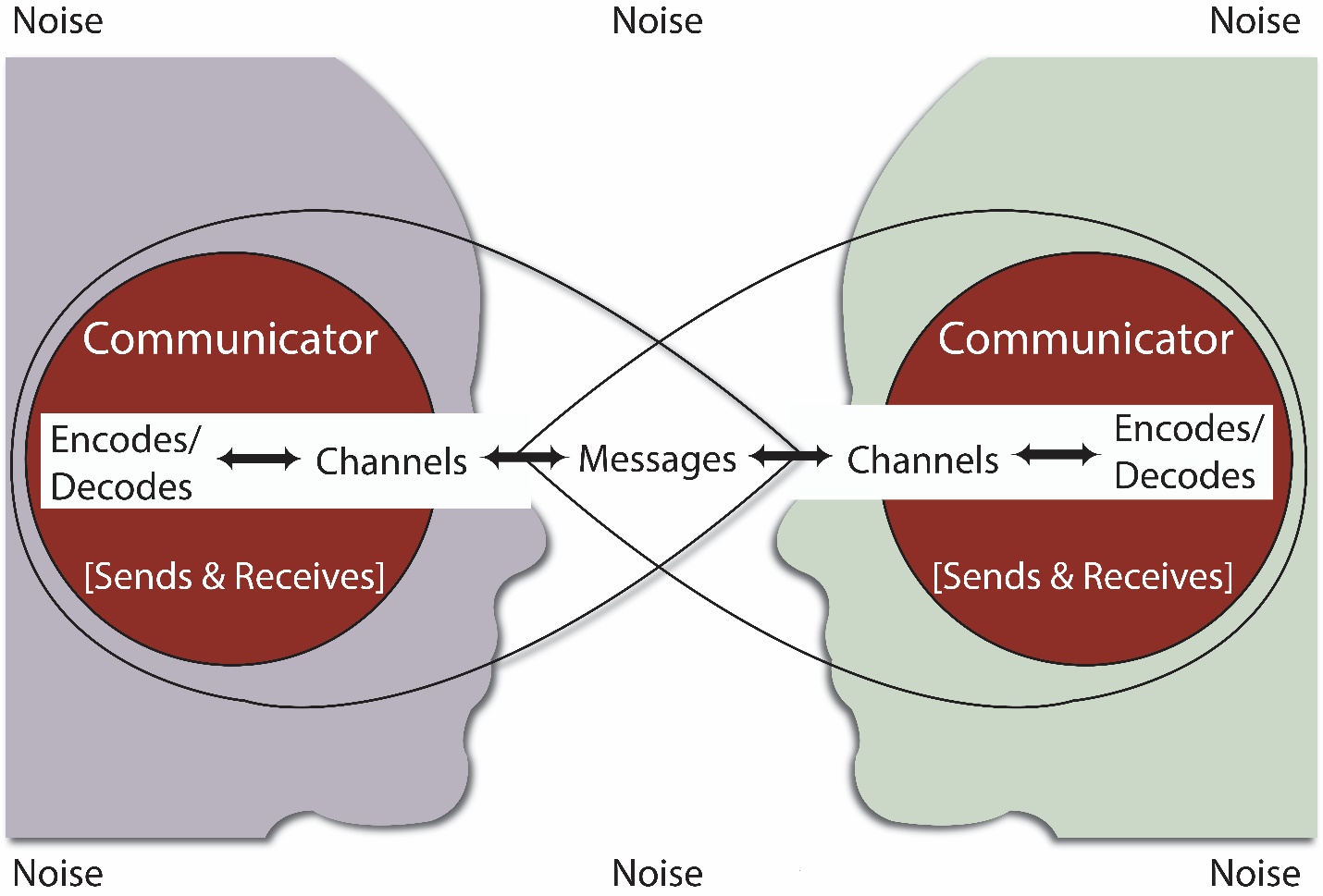

Barnlund’s Transactional Model

In 1970, Dean C. Barnlund created the transactional model of communication to understand basic interpersonal communication.17 Barnlund argues that one of the problems with the more linear models of communication is that they resemble mediated messages. The message gets created, the message is sent, and the message is received. For example, we write an email, we send an email, and the email is read. Instead, Barnlund argues that during interpersonal interactions, we are both sending and receiving messages simultaneously. Out of all the other communication models, this one includes a multi-layered feedback system. We can provide oral feedback, but our nonverbal communication (e.g., tone of voice, eye contact, facial expressions, gestures, etc.) is equally important to how others interpret the messages we are sending we use others’ nonverbal behaviors to interpret their messages. As such, in any interpersonal interaction, a ton of messages are sent and received simultaneously between the two people.

The Importance of Cues

The main components of the model include cues. There are three types of cues: public, private, and behavioral. Public cues are anything that is physical or environmental. Private cues are referred to as the private objects of the orientation, which include the senses of a person. Behavioral cues include nonverbal and verbal cues.

The Importance of Context

Furthermore, the transactional model of communication has also gone on to represent that three contexts coexist during an interaction:

- Social Context: the rules and norms that govern how people communicate with one another.

- Cultural Context: the cultural and co-cultural identities people have (e.g., ability, age, biological sex, gender identity, ethnicity, nationality, race, sexual orientation, social class, etc.).

- Relational Context: the nature of the bond or emotional attachment between two people (e.g., parent/guardian-child, sibling-sibling, teacher-student, health care worker-client, best friends, acquaintances, etc.).

Through our interpersonal interactions, we create social reality, but all of these different contexts impact this reality.

The Importance of Noise

Another important factor to consider in Barnlund’s Transactional Model is the issue of noise, which includes things that disturb or interrupt the flow of communication. Like the three contexts explored above, there are another four contexts that can impact our ability to interact with people effectively:18

- Physical Context: The physical space where interaction is occurring (office, school, home, doctor’s office, is the space loud, is the furniture comfortable, etc.).

- Physiological Context: The body’s responses to what’s happening in its environment.

- Internal: Physiological responses that result because of our body’s internal processes (e.g., hunger, a headache, physically tired, etc.).

- External: Physiological responses that result because of external stimuli within the environment (e.g., are you cold, are you hot, the color of the room, are you physically comfortable, etc.).

- Psychological Context: How the human mind responds to what’s occurring within its environment (e.g., emotional state, thoughts, perceptions, intentions, mindfulness, etc.).

- Semantic Context: The possible understanding and interpretation of different messages sent (e.g., someone’s language, size of vocabulary, effective use of grammar, etc.).

In each of these contexts, it’s possible to have things that disturb or interrupts the flow of communication. For example, in the physical context, hard plastic chairs can make you uncomfortable and not want to sit for very long talking to someone. Physiologically, if you have a headache (internal) or if a room is very hot, it can make it hard to concentrate and listen effectively to another person. Psychologically, if we just broke up with our significant other, we may find it difficult to sit and have a casual conversation with someone while our brains are running a thousand kilometers a minute. Semantically, if we don’t understand a word that someone uses, it can prevent us from accurately interpreting someone’s messages. When you think about it, with all the possible interference of noise that exists within an interpersonal interaction, it’s pretty impressive that we ever get anything accomplished.

More often than not, we are completely unaware of how these different contexts create noise and impact our interactions with one another during the moment itself. For example, think about the nature of the physical environments of fast-food restaurants versus fine dining establishments. In fast-food restaurants, the décor is bright, the lighting is bright, the seats are made of hard surfaces (often plastic), they tend to be louder, etc. This noise causes people to eat faster and increase turnover rates. Conversely, fine dining establishments have tablecloths, more comfortable chairs, dimmer lighting, quieter dining, etc. The physical space in a fast-food restaurant hurries interaction and increases turnover. The physical space in the fine dining restaurant slows our interactions, causes us to stay longer, and we spend more money as a result. However, most of us don’t pay that much attention to how physical space is impacting us while we’re having a conversation with another person.

Although we used the external environment here as an example of how noise impacts our interpersonal interactions, we could go through all of these contexts and discuss how they impact us in ways of which we’re not consciously aware.

Transaction Principles

As you can see, these models of communication are all very different. They have similar components, yet they are all conveyed very differently. Some have features that others do not. Nevertheless, there are transactional principles that are important to learn about interpersonal communication.

Communication is Complex

People might think that communication is easy. However, there are a lot of factors, such as power, language, and relationship differences, that can impact the conversation. Communication isn’t easy because not everyone will have the same interpretation of the message. You will see advertisements that some people will love and others will be offended by. The reason is that people do not identically receive a message.

Communication is Continuous

In many of the communication models, we learned that communication never stops. Every time a source sends a message, a receiver will decode it, and it goes back-and-forth. It is an endless cycle because even if one person stops talking, they have already sent a message that the communication needs to end. As a receiver, you can keep trying to send messages, or you can stop talking as well, which sends the message to the other person that you also want to stop talking.

Communication is Dynamic

With new technology and changing times, we see that communication is constantly changing. Before social media, people interacted very differently. Some people have suggested that social media has influenced how we talk to each other. The models have changed over time because people have also changed how they communicate. People no longer use the phone only to call other people; instead, they might text message others because they find it easier or less invasive.

Final Note

The advantage of this model is it shows that there is a shared field of experience between the sender and receiver. The transactional model shows that messages happen simultaneously with noise. However, the disadvantages of the model are that it is complex, and it suggests that the sender and receiver should understand the messages that are sent to each other.

Key Takeaways

- In action models, communication was viewed as a one-directional transmission of information from a source or sender to some destination or receiver. These models include the Shannon and Weaver Model, the Schramm Model and Berlo’s SMCR model.

- Interactional models viewed communication as a two-way process, in which both the sender and the receiver equally share the responsibility for communication effectiveness. Examples of the interactional model are Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson Model and Osgood and Schramm Model.

- The transactional models differ from the interactional models in that the transactional models demonstrate that individuals are often acting as both the sender and receiver simultaneously. An example of a transactional model is Barnlund’s model.

Exercises

- Choose one action model, one interactional model, and Barnlund’s transactional model. Use each model to explain one communication scenario that you create. What are the differences in the explanations of each model?

- Choose the communication model with which you most agree. Why is it better than the other models?

Key Terms

action model

Communication model that views communication as a one-directional transmission of information from a source or sender to some destination or receiver.

attending

The act of focusing on specific objects or stimuli in the world around you.

channel

The pathways in which messages are conveyed.

emotional intelligence

People who are aware of their emotions and are sensitive to the emotions of others are better able to handle the ups and downs of life, to rebound from adversity, and to maintain fulfilling relationships with others.

environment

The context or situation in which communication occurs.

ethics

The set of moral values each person carries throughout life—concepts of what is right and wrong, good and bad, or just and unjust.

feedback

Information shared back to the source of communication that keeps the communication moving forward and thus making communication a process.

interaction model

Communication model that views the sender and the receiver as responsible for the effectiveness of the communication.

interpreting

Interpretation is the act of assigning meaning to a stimulus and then determining the worth of the object (evaluation).

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Theory of motivation proposed by Abraham Maslow comprising a five-tier, hierarchical pyramid of needs: physiological, safety, love, esteem, and self-actualization.

model

A simplified representation of a system (often graphic) that highlights the important components and connections of concepts, which are used to help people understand an aspect of the real-world.

noise

Anything that can interfere with the message being sent or received.

organizing

Organizing is making sense of the stimuli or assigning meaning to it.

perception

The process of acquiring, interpreting, and organizing information that comes in through your five senses.

receiver

The receiver decodes the message in an environment that includes noise.

source

The person initiating communication and encoding the message and selecting the channel.

transactional model

Communication model that demonstrate that individuals are often acting as both the sender and receiver simultaneously.

Chapter Wrap-Up

In this chapter, we have learned about various things that can impact interpersonal communication. We learned that Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs can impact how messages are received. We learned about the perception process and the three states of the perception process: attending, interpreting, and organizing. We also discussed the various communication models to understand how the process of communication looks in interpersonal situations.

Notes

Media Attributions

- Maslow’s hierarchy of needs © Saul McLeod is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- The Rubin Vase – based on Edgar John Rubin’s (1915) “Vase Ambiguous Figure” © Edgar John Rubin is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Charles Allan Gilbert “All is Vanity” © Charles Allan Gilbert is licensed under a Public Domain license

- “My Wife and My Mother-in-Law” © William Ely Hill is licensed under a Public Domain license

The person initiating communication and encoding the message and selecting the channel.

The receiver decodes the message in an environment that includes noise.

The pathways in which messages are conveyed.

Information shared back to the source of communication that keeps the communication moving crward and thus making communication a process.

The context or situation in which communication occurs.

Anything that can interfere with the message being sent or received.

The process of acquiring, interpreting, and organizing information that comes in through your five senses.

The act of focusing on specific objects or stimuli in the world around you

Organizing is making sense of the stimuli or assigning meaning to it.

Interpretation is the act of assigning meaning to a stimulus and then determining the worth of the object (evaluation).

A simplified representation of a system (often graphic) that highlights the important components and connections of concepts, which are used to help people understand an aspect of the real-world.

Communication model that views communication as a one-directional transmission of information from a source or sender to some destination or receiver.

Communication model that views the sender and the receiver as responsible for the effectiveness of the communication.

Communication model that demonstrate that individuals are often acting as both the sender and receiver simultaneously.