Chapter 10: Letter Writing

Will Fleming

This chapter will examine formal letters, focusing on cover letters. In the following video, “Writing in the Workplace, Pt. 1,” University of California alumni talk about how writing skills learned in college apply to their everyday work and career development:

McGraw, Darrin and Knight, Tara, directors. "Writing in the Workplace Pt. 1." UC San Diego. Uploaded by SixthCATatUCSD, 5 June 2009, Youtube.com. |

10.1 Business Letters (General)

Writing business letters may be quite different from writing that you may have done in the humanities, social sciences, or other academic disciplines. Technical writing often strives to be clear and concise rather than evocative or creative; it stresses specificity, accuracy, and audience awareness. Nevertheless, business letters still need to persuade readers to take action or to agree to a proposition. In Chapter 2, we looked at how stylistic elements and choices affect the message of a tweet; here we examine the stylistic choices (layout, word choice, grammar, etc.) that might affect the message of a letter.

When you write a business letter, you can assume that your readers have limited time to read it and are likely to skim the document in search of its main points. They want to know why you’re writing and what they need to do in response. The sections below provide guidelines for effectively formatting and structuring the standard block-style business letter.

Common Components of Business Letters

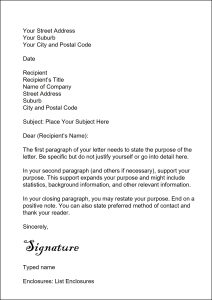

Heading: The heading contains the writer’s address and the date of the letter. The writer’s name is not included. If you are using a letterhead that includes your address, only a date is needed.

Inside address: The inside address shows the name and address of the recipient of the letter. This information can help prevent confusion at the recipient’s offices. Also, if the recipient has moved, the inside address helps to determine what to do with the letter. In the inside address, include the highest honorific for the recipient (particularly for first contact) and copy the name of the company exactly as that company writes it:

-

- Ms. (any woman regardless of marital status)

- Mr. (any man regardless of marital status)

- Dr. (a PhD or MD)

- Prof. (a higher rank bestowed on some academics)

- Rev. (some Christian clergy)

- Hon. (judges of the High Court of New Zealand)

- Rt. Hon. (The Governor General, The Chief Justice, etc.)

If you are not sure what is correct for an individual, try to find out how that individual signs letters or consult the forms-of-address section in a dictionary.

Salutation: The salutation directly addresses the recipient of the letter and is followed by a colon or a comma. If you don’t know whether the recipient is a man or a woman, the traditional practice has been to write “Dear Sir” or “Dear Sirs”–but that’s exclusionary. To avoid this problem, salutations such as “Dear Sir or Madame,” “Dear Ladies and Gentlemen,” “Dear Friends,” or “Dear People” have been tried–but without much general acceptance. Deleting the salutation line altogether or inserting “To Whom It May Concern” in its place, is not ordinarily a good solution either–it’s impersonal.

The best solution is to call to the organization and ask for a name or to do a web search for the individual in the role. Less effectively, you couldor address the salutation to a department name, committee name, or a position name: “Dear Personnel Department,” “Dear Recruitment Committee,” “Dear Chairperson,” or “Dear Director of Financial Aid,” for example.

Subject or reference line: The subject line announces the main business of the letter.

Body of the letter: The actual message, of course, is contained in the body of the letter–the paragraphs between the salutation and the complimentary close.

Complimentary close: The “Sincerely yours” element of the business letter is called the complimentary close. Other common ones are “Sincerely yours,” “Sincerely,” “Cordially,” “Respectfully,” or “Respectfully yours.” Notice that only the first letter of the complimentary close is capitalized, and it is always followed by a comma.

Signature block: Usually, you type your name four lines below the complimentary close and sign your name in between. If you identify as female and want to make your marital status clear (which is becoming increasingly rare unless there is a reason to do so), use Miss (unmarried) or Mrs. (married) before the typed version of your first name. Whenever possible, include your title or the name of the position you hold just below your name. For example, “Technical writing student,” “Sophomore data processing major,” or “Tarrant County Community College Student” are perfectly acceptable.

End notations: Just below the signature block are often several abbreviations or phrases that have important functions.

-

- Initials: The initials in all capital letters in the preceding figures are those of the writer of composer of the letter, and the ones in lower case letters just after the colon are those of the typist.

- Enclosures: To make sure that the recipient knows that items accompany the letter in the same envelope, use such indications as “Enclosure,” “Encl.,” “Enclosures (2).” For example, if you send a resume and writing sample with your application letter, you’d write this: “Encl.: Resume and Writing Sample.” If the enclosures are lost, the recipient will know.

- Copies: If you send copies of a letter to others, indicate this fact among the end notations also. If, for example, you were upset by a local merchant’s handling of your repair problems and were sending a copy of your letter to the Better Business Bureau, you’d write something like this: “cc: Mr. Raymond Mason, Attorney.”

Note the example of a properly formatted block style business letter:

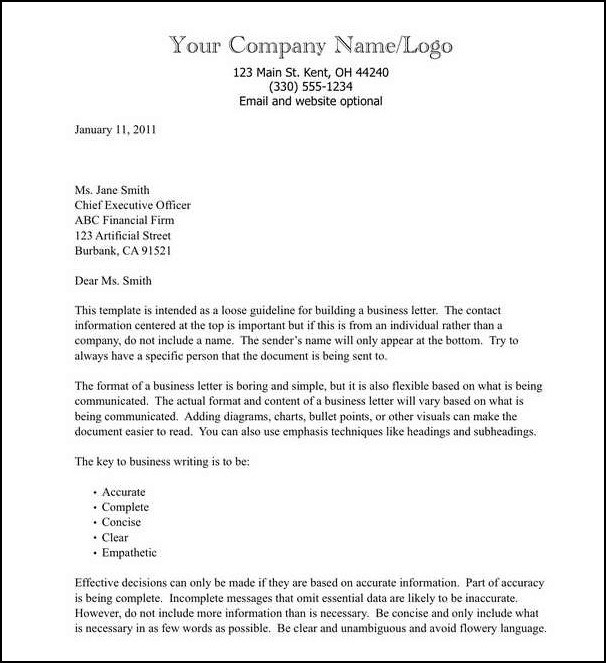

The following is another example of a properly formatted business letter: Block Style Letter Sample

For more information, watch the following video, “Writing the Basic Business Letter,” from Upwrite Press:

Formatting Tips for Business Letters

- Use white space to draw attention to headings. White space helps show what elements on your page are the most important. It’s also easier on readers’ eyes.

- Add white space between paragraphs. Adding white space between paragraphs and around blocks of text and images makes documents easier to read and navigate; it also helps people understand what they’re reading.

- Widen the margins. Generally speaking, widening the margins can help readability—sometimes putting less information on the page is less daunting to the reader.

- Use bullet points when appropriate. Bullet points aren’t appropriate for all information, but they are generally helpful to readers by helping to identify important points in the document.

In this figure note the use of the visual elements described above:

General Tips for Writing and Revising Business Correspondence

Keep the following points in mind when you write and revise your business letters or memos.

State the main business, purpose, or subject matter right away. Let the reader know from the very first sentence what your letter is about. Remember that when business people open a letter, their first concern is to know what the letter is about, what its purpose is, and why they must spend their time reading it. Therefore, avoid round-about beginnings. If you are writing to apply for a job, begin with something like this: “I am writing to apply for the Sales Manager position (Job #84491) as advertised on Student Job Search.” If you have bad news for someone, you should need not spill all of it in the first sentence. Here is an example of how to avoid negative phrasing: “I am writing in response to your letter of July 24 in which you discuss problems you have had with an electronic spreadsheet purchased from our company.” We will discuss buffers further in lectures.

If you are responding to a letter, identify that letter by its subject and date in the first paragraph or sentence. Busy recipients who write many letters themselves may not remember their letters to you. To avoid problems, identify the date and subject of the letter to which you respond: “I am writing in response to your 1 September 2019 letter in which you describe problems you’ve had with one of our products.”

Keep the paragraphs of most business letters short. The paragraphs of business letters tend to be short, some only a sentence long. Business letters are not read the same way as articles, reports, or books. Usually, they are read rapidly. Big, thick, dense paragraphs over ten lines, which require much concentration, may not be read carefully—or read at all.

To enable the recipient to read your letters more rapidly and to comprehend and remember the important facts or ideas, create relatively short paragraphs of between three and eight lines long. In business letters, paragraphs that are made up of only a single sentence are common and perfectly acceptable.

Compartmentalize the contents of your letter. When you compartmentalize the contents of a business letter, you place each different segment of the discussion—each different topic of the letter—in its own paragraph. If you were writing a complaint letter concerning problems with the system unit of your personal computer, you might have the following paragraphs:

-

-

- A description of the problems you’ve had with it

- The ineffective repair jobs you’ve had

- The compensation you think you deserve and why

-

Study each paragraph of your letters for its purpose, content, or function. When you locate a paragraph that does more than one thing, consider splitting it into two paragraphs. If you discover two short separate paragraphs that do the same thing, consider joining them into one.

Provide topic indicators at the beginning of paragraphs. Analyze some of the letters you see in this chapter in terms of the contents or purpose of their individual paragraphs. In the first sentence of anybody paragraph of a business letter, try to locate a word or phrase that indicates the topic of that paragraph. If a paragraph discusses your problems with a personal computer, work the word “problems” or the phrase “problems with my personal computer” into the first sentence. Doing this gives recipients a clear sense of the content and purpose of each paragraph. Here is an excerpt before and after topic indicators have been incorporated:

Problem: I have worked as an electrician in the Decatur, Illinois, area for about six years. Since 2005 I have been licensed by the city of Decatur as an electrical contractor qualified to undertake commercial and industrial work as well as residential work.

Revision: As for my work experience, I have worked as an electrician in the Decatur, Illinois, area for about six years. Since 2005 I have been licensed by the city of Decatur as an electrical contractor qualified to undertake commercial and industrial work as well as residential work.

List or itemize whenever possible in a business letter. Listing spreads out the text of the letter, making it easier to pick up the important points rapidly.

Place important information strategically in business letters. Information in the first and last lines of paragraphs tends to be read and remembered more readily. These are high-visibility points. Information buried in the middle of long paragraphs is easily overlooked or forgotten. For example, in application letters which must convince potential employers that you are right for a job, place information on your appealing qualities at the beginning or end of paragraphs for greater emphasis. Place less positive information in less highly visible points. If you have some difficult things to say, a good (and honest) strategy is to de-emphasize by placing them in areas of less emphasis (such as by placing them in a subordinate clause). If a job requires three years of experience and you only have one, for example, you could bury this fact in the middle or the lower half of a body paragraph of the cover letter (the following sections of this chapter will discuss job application/cover letters in more detail).

Focus on the recipient’s needs, purposes, or interests instead of your own. Avoid a self-centered focus on your own concerns rather than those of the recipient. Even if you must talk about yourself in a business letter a great deal, do so in a way that relates your concerns to those of the recipient. This recipient-oriented style is often called the “you-attitude,” which does not mean using more “you” but making the recipient the main focus of the letter.

Avoid pompous, inflated, legal-sounding phrasing. Watch out for puffed-up, important-sounding language unless you are using technical terms expected by the reader’s discourse community. For example, some phrasing may be expected in legal documents; but why use it in other writing situations? When you write a business letter, you should to strive for confidence while avoiding arrogance.

*A note on style: Technical writing can vary from a less formal, more conversational style to a more formal, or even legalistic, style found in documents such as contracts and business plans. Writing that is too formal can alienate readers while overly casual writing can come across as insincere or unprofessional. When writing business letters, as with all writing, you should know your audience. Adopting a style somewhere between formal and conversational will work well for the majority of your memos, emails, and business letters.

Give your business letter an “action ending” whenever appropriate. An “action-ending” makes clear what the writer of the letter expects the recipient to do and when. Ineffective conclusions to business letters often end with noncommittal statements, such as “Hope to hear from you soon” or “Let me know if I can be of any further assistance.” Instead, specify the action the recipient should take and the schedule for that action.

As soon as you approve this plan, I’ll begin contacting sales representatives at once to arrange for purchase and delivery of the notebook computers. May I expect to hear from you by Friday, 1 June?

Additional Resources

- “Writing the Basic Business Letter,” a website resource from Purdue OWL

- “Types of Business Letters,” a video from Gregg Learning

CHAPTER ATTRIBUTION INFORMATION"2.1 Business Correspondence." Open Technical Writing. [License: CC BY 4.0] "The Key Forms of Business Writing." Uploaded by UpWritePress, 6 Mar. 2009, Youtube.com. |

10.2 Cover Letters

This chapter focuses on the cover letter (sometimes called an application letter), which typically accompanies your resume in an employment package. In fact, your cover letter is often the potential employer’s first introduction to you.

The purpose of the cover letter is to draw a clear connection between the job you are seeking and your qualifications listed on the resume. Put another way, your cover letter should match the requirements of the job with your qualifications, emphasizing how you are right for that job.

*NOTE: The cover letter is not simply a lengthier or narrative version of your resume. The cover letter should selectively illustrate how the information contained in the resume is relevant to the position.

Common Types of Cover Letters

To begin planning your letter, decide which type of letter you need. This decision is, in part, based on the employers’ requirements and, in part, based on what your background and employment needs are. Here are the two most common cover letter types:

-

-

- Objective letters: This type of letter says very little: it identifies the position being sought, indicates an interest in having an interview, and calls attention to the fact that the résumé is attached. It also mentions any other special matters that are not included on the résumé, such as dates and times when you are available to come in for an interview. This letter does no salesmanship and is very brief.

-

-

-

- Highlight letters: This type of letter (the type you would do in most technical writing courses) tries to summarize the key information from the résumé, key information that will emphasize how you are a good candidate for the job. In other words, it selects the best information from your résumé and summarizes it in the letter—this type of letter is especially designed to make the connection with the specific job.

-

Common Sections in Cover Letters

As for the actual content and organization of the paragraphs within the application letter (specifically for the highlight type of application letter), consider the following common approaches.

-

-

- Introductory paragraph: That first paragraph of the application letter is the most important; it sets everything up—the tone, focus, as well as your most important qualification. A typical problem in the introductory paragraph involves diving directly into your work and educational experience. A better idea is to do some combination of the following in the space of a very short paragraph (some introductory paragraphs are a single sentence):

- State the purpose of the letter—to apply for an employment opportunity.

- Indicate the source of your information about the job—a website posting, a newspaper ad, a personal contact, or other.

- State one attention-getting thing about yourself in relation to the job or to the employer that will cause the reader to want to continue.

- Main body paragraphs: In the main parts of the application letter, you present your work experience, education, and training—whatever makes that connection between you and the job you are seeking. Remember that this is the most important job you have to do in this letter—to enable the reader to see the match between your qualifications and the requirements for the job.

- Introductory paragraph: That first paragraph of the application letter is the most important; it sets everything up—the tone, focus, as well as your most important qualification. A typical problem in the introductory paragraph involves diving directly into your work and educational experience. A better idea is to do some combination of the following in the space of a very short paragraph (some introductory paragraphs are a single sentence):

-

Author Steven Graber in his article “The Basics of A Cover Letter” suggests the following points for developing your cover letter’s body paragraphs:

-

-

- First (Introductory): “State the position for which you’re applying. If you’re responding to an ad or listing, mention the source.”

- Second: “Indicate what you could contribute to this company and show how your qualifications will benefit them.…discuss how your skills relate to the job’s requirements. Don’t talk about what you can’t do.”

- Third: “Show how you not only meet but exceed their requirements—why you’re not just an average candidate but a superior one.”

- Fourth: “Close by saying you look forward to hearing from them” and “thank them for their consideration. Don’t ask for an interview. Don’t tell them you’ll call them.”

- Closing: “Keep it simple—‘Sincerely’ followed by a comma suffices.”

-

There are two common ways to present this information:

-

-

- Functional approach: This one presents education in one section and work experience in the other. Whichever of these sections contains your “best stuff” should come first, after the introduction.

-

-

-

- Thematic approach: This one divides experience and education into groups such as “management,” “technical,” “financial,” and so on and then discusses your work and education related to them in separate paragraphs.

-

Of course, the letter should not be an exhaustive or complete summary of your background—it should highlight just those aspects of your background or experience that make the connection with the job you are seeking.

General Guidelines for Writing Successful Cover Letters

-

-

- Specify what it is you want (to apply for the position, inquire about a summer internship, etc.);

- Explain how/where you learned of the position;

- Highlight key areas of your education and professional experience (volunteer work counts!);

- Be as specific as possible, using examples when appropriate;

- Use language that is professional and polite;

- Demonstrate your enthusiasm and energy with an appropriate tone;

- Use simple and direct language whenever possible, using clear subject-verb-structured sentences;

- Appeal to the employer’s self-interest by showing that you have researched the company or organization;

- State how you (and perhaps only you) can fulfill their needs, telling them why you’re the best candidate;

- Give positive, truthful accounts of accomplishments and skills that relate directly to the field or company;

- Stress what you have done rather than what you haven’t and what you do have rather than what you don’t (in other words, don’t apologize for your lack of experience, expertise, or education);

- Emphasize what you can and will do rather than what you cannot or will not;

- Highlight what you can do specifically for the company/organization rather than why you want the job.

-

Length

A cover letter can be fairly short (usually a single page, but this is not a rule). It should be long enough to provide a detailed overview of who you are and what you bring to the company.

Accentuate the positive

Your cover letters will be more successful if you focus on positive wording rather than negative simply because most people respond more favorably to positive ideas than to negative ones. Words that affect your reader positively are more likely to produce the response you want. A positive emphasis helps persuade readers and create goodwill.

In contrast, negative words may generate resistance and other unfavorable reactions. You should therefore be careful to avoid words with negative connotations. These words either deny—for example, no, do not, refuse, and stop—or convey unhappy or unpleasant associations—for example, unfortunately, unable to, cannot, mistake, problem, error, damage, loss, and failure. Be careful in your cover and/or inquiry letters of saying things like, “I know I do not have the experience or credentials you are looking for in this position…” These kinds of statements focus too much on what you don’t have rather than what you do. Also, don’t call attention to gaps in employment—let that come up in the interview.

*NOTE: Just because your résumé will be attached, don’t make the all-too-common mistake of thinking that your resume should or will do all the work. If something is important, be sure to discuss it in your cover letter because there’s no guarantee that your reader will even look at your resume. Part of your task in crafting a cover letter is to keep your reader interested and engaged.

Additional resources

- “Cover Letter” from Purdue OWL

Reference

Graber, Steven. “The Basics of A Cover Letter.” Strategies for Business and Technical Writing, edited by Kevin Harty, Pearson, 2011.

Material in this chapter is adapted from “Job Application Letters.” Online Technical Writing. [License: CC BY 4.0] “Tips for Creating A Great Cover Letter.” Uploaded by GCFLearnFree.org, 29 May 2018, Youtube.com.

Media Attributions

- Letter 3

- Formatted business letter © Will Fleming