Chapter 2: Understanding and Persuading Your Audience: Credibility, Emotions, and Logic

In selecting a gif and opening paragraph for this chapter, I had two goals: (1) I wanted you to continue reading so that (2) you might engage the concepts of this class. To achieve these two goals, I had to consider what your emotional reaction might be to a topic that I consider important but that you might think is dry. I chose a gif that suggested friendliness and my excitement about the topic. That is, even before I started discussing the topic at hand, I was considering your disposition towards that topic and towards me.

I could have chosen this gif, one that also is largely black and white and that has someone gesturing “hi”:

Would you have had the same motivation to continue reading? Perhaps. Maybe you would have found this gif less friendly but more intriguing. Maybe other factors would keep you reading (e.g., you need to read the chapter to get marks, you are genuinely interested in persuasion, you genuinely love terrifying clowns, etc.). Perhaps not. Maybe you would have had a strong emotional reaction to the gif (if, for example, you are afraid of clowns) or maybe you might think that an academic author who starts a chapter with a gimmicky gif isn’t credible enough for you to keep reading.

Persuasion is the communicative act of swaying someone to agree with your point of view or to act in a certain way. We make numerous rhetorical choices when we communicate–even in something as simple as starting a conversation with “hi” so that we can build to more difficult concepts. The communication choices that we make will help or hinder us from achieving our goal.

When choosing the gif with which I wanted to open this chapter, I had to consider the traditional methods of persuasion, which were first and famously delineated more than 2000 years ago by the Greek philosopher, Aristotle. In Rhetorica, Aristotle argued that “Of the modes of persuasion furnished by the spoken word there are three kinds: ethos, pathos, and logos” (1356a). While Aristotle related these three approaches to spoken discourse, we can employ these three persuasive approaches in any “text” (anything that we can “read” or interpret). This chapter will explore those three persuasive approaches: ethos (credibility/ethical), pathos (emotional), and logos (logical).

Audience and Traditional Persuasive Appeals

Ethos (Credibility/Ethical Appeal)

Ethos (ἦθος) refers to the perceived credibility of speakers and of their topics: “Persuasion is achieved by the speaker’s personal character when the speech is so spoken as to make us think him [sic] credible” (1365a). In other words, the credentials, expertise, and demeanor of a speaker can inspire an audience to believe or be persuaded by that speaker. Ideally, our audiences will perceive us as credible people whose texts are worth looking at, listening to, or reading.

You can achieve credibility through the information you present and through the way you present yourself:

- Being knowledgeable and demonstrating your expertise about your topic:

- Discover as much as you can and pare down that knowledge rather than knowing the bare minimum and bulking it out.

- Provide plentiful and credible evidence.

- Understand the opinions both for and against your topic.

- Demonstrate the source(s) of your own expertise by showing what makes you someone worthy of listening to about the subject matter.

- Presenting yourself as trustworthy:

- Ensure that you accurately relay and cite that information when you use someone else’s information.

- Avoid making false statements.

- Be empathetic.

- Acknowledge that your view is not the only possible view.

- Treat others–and their work–with dignity, even if you disagree; avoid ad hominem attacks.

Pathos (Emotional Appeal)

While ethos emanates from you, persuading by pathos (πάθος) means trying to stir the desired emotion in your audience: “persuasion may come through the hearers, when the speech stirs their emotions. Our judgements when we are pleased and friendly are not the same as when we are pained and hostile” (1356a). Humans experience numerous emotions, though, and all of those emotions can be persuasive in motivating the action or response for which you are aiming: anger, contentment, despair, fear, love, sadness, shame.

Emotional appeals can be difficult to manage well, particularly when your audience is either exceptionally diverse in outlook or hostile to you and/or your position on the topic at hand. A diverse group of people may have varied emotional reactions to the same topic and anecdotes or examples you might use. For instance, imagine that you want to persuade an audience of 100 New Zealanders from households across the country that we need to provide better protections for native birds. After all, the Department of Conservation estimates that “25 million native birds in New Zealand are killed each year by rats, stoats, possums and other introduced predators” (2024, 1). That list might elicit anger or helplessness for Kiwis who value New Zealand’s green image because that list comprises predatory animals towards which few people feel affection or sympathy. If you were to add domestic cats to that list, though, there’s a chance that up to forty people in your audience might have a different emotional reaction because New Zealand has one of the highest rates of cat ownership globally–with roughly 40% of households owning at least one cat. According to an article in The Guardian (2022), pet cats might account for over a million of those native bird deaths per year. If you added cats to that list of vicious predators slaughtering native birds, would a large portion of your audience feel shame, and would that shame work for your argument (prompting them to keep their cats indoors) or against your argument (turning to defensiveness against you and your case for inspiring those uncomfortable feelings)? That is, you might be able to guess that your examples or topic will elicit a potentially strong emotional response, but understanding what people do with those emotions can be tricky.

Logos (Logical Appeal)

Logos (λόγος) is the logical character of the content itself: “persuasion is effected through the speech itself when we have proved a truth or an apparent truth by means of the persuasive arguments suitable to the case in question” (1365a). To persuade, we need to provide suitable (credible!) examples or use appropriate reasoning.

Let’s consider the quantity and type of examples you use that lead to a claim, or enumerative induction. I suggest enumerative induction because it is the type of reasoning with and in which you are already most familiar and practiced. For example, when you were learning to write argumentative paragraphs, your writing teacher may have told you that you need to provide sufficient examples in your writing (evidence) and that your topic sentence should be a claim about those examples (argument). Depending on how you went about gathering those examples and making that claim, you may have been practicing enumerative induction. Enumerative induction is where we make a series of observations, and, based on that series of observations, we make a general claim; the greater the number of observations that we have made, the stronger the claim.

Say you bite into a green apple, and it’s tart.

You pick up another green apple, bite it, and find that it’s tart, too.

You pick up yet another green apple and bite into it: once again, tart!

Those three fruit are all slightly different, but they are similar enough for you to observe that:

Those three fruit are all slightly different, but they are similar enough for you to observe that:

- They are all green,

- They are all apples, and

- They are all tart.

You might begin to surmise that, in general, green apples are tart. Now, your collection of three green apples isn’t a lot of support for that conclusion, so you continue to try more and more green apples to strengthen that conclusion. The more green apples that you bite into and that turn out to be tart, the more confidently you’ll be able to stake a claim.

There are limits to this type of reasoning. The first we have already alluded to: how many apples make a strong claim? Moreover, even if you have tried a literal ton of apples, can you realistically make a claim about every single green apple in existence based on your evidence? For example, have you tried numerous different types of green apples: Granny Smith, Ginger Gold, Crispin, and so on? If you tried one of each, would each of those apples be representative of its type? Had the apple reached full ripeness before you tried it? Is there a counterexample: is there a type of green apple that is sweet rather than tart? Also, how long can your claim hold: can you reasonably predict future forms of green apples based on the wagonful of apples that you have tried today?

When you attempt to persuade with such a logical appeal, your figurative pile of apples also needs to include apples that your audience accepts as apples. If you include a quince as an example of how green apples are tart (after all, quinces are green fruit from the same family as apples, and quinces can taste reasonably tart), you might be able to fool your audience into thinking you have provided yet another good example, but equally your audience might recognize that quinces are not apples, and your credibility (and support) will suffer.

Moreover, do you know that your evidence comes from credible sources? Your evidence needs to come from trusted apple growers–ones that do not simply paint red apples green or that inject them with artificial flavoring. Again, if your audience discovers that your apples have been modified, your credibility (and support) will suffer.

In less figurative terms, you need to have enough examples from sources that are known to be accurate and thorough and, in an ideal world, that will resonate (emotionally and ethically) with your audience. Then, you need to relay the information from those sources accurately and cite them clearly (more on citations in Chapter 8) to put them into service of persuading your audience to feel, do, or think what you want them to.

Goals and Audience

In order to persuade someone to believe your point of view or act in a certain way, you first need to be clear about what your point of view is or how you want someone to act; it’s hard to get what you want if you don’t know precisely what you want.

Knowing what you’re aiming for is only the first step. You need to identify as precisely as possible how your audience might feel about that goal. Knowing your audience well will likely be the determining factor in whether you are able to achieve your goal, for what succeeds with one audience might fail miserably with another.

There are numerous ways of assessing your audience. You may, for example, consider the power dynamics between you and them (or among them): who has more authority? Who makes the final decision? Who may not be able to make decisions but has influence over the decision-makers? You may also consider your audience’s apparent disposition to your topic: are they supportive, wavering, indifferent, or hostile? If you cannot know the power structure or disposition of your audience, you may think in the four broader socio-economic terms (among others such as religion, occupation/vocation, income, etc.). As with any broad categories, they can be only roughly accurate:

Age: how old is your audience? People at different stages of life may have different concerns. For example, fifty-somethings may have financial concerns about paying mortgages or planning for their retirement; those concerns might lead them to buy the rental properties that you, as a student, are paying for with your rent. Your outlooks about that same rental property may therefore differ significantly.

People of different ages are also likely to have different lived experiences and reactions to those lived experiences. For instance, fifty-somethings may recall their reactions to the Chernobyl disaster, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Tiananmen Square massacre, the advent of the first internet browser, the launch of Wikipedia, the 9/11 attacks, Arab Spring, and the COVID pandemic. If you have just entered your first year at university straight from high school, you may recall only the last two. While you will certainly be familiar with the other historic events in that list, your emotional responses to them might well differ from those who remember them unfolding in real time.

Education: what does your audience know about your topic? What your audience knows will determine how much information you need to include or to explain and how you will explain it. Imagine, for instance, that you are creating a text arguing for a decrease in New Zealand’s reliance on cars as a dominant means of transportation. If you were creating that text for a general cross-section of our society, you would have to start with some basic information because not everyone will have studied or read about the issue. You might need to establish how many vehicles there are per capita: as of 2021, there were 889 vehicles per 1,000 people–one of the highest rates of vehicle ownership in the world. You might make sense of that number for the members of your audience as they might not understand where that number fits globally, noting that most of the other nations with higher rates are small states such as San Marino, Guernsey, Gibraltar, Jersey, Liechtenstein, and Andorra. However, if you were trying to persuade Te Manatū Waka Ministry of Transport, you likely would not need to include that information because it comes from their Annual Fleet Statistic document for 2021. To do so would illustrate a lack of awareness of who your audience is and what they already know.

Culture: culture is not synonymous with race or nationality; rather, culture comprises all of the shared beliefs, goals, arts, institutions, and social practices of a community, whether that community be relatively small and local (such as students at the University of Otago) or more large-scale (such as New Zealanders as whole). Ideals and outlooks can sometimes conflict between cultures of any size. In those examples, students of Otago are also part of the greater New Zealand culture, a culture that tends to support those in need through benefits such Work and Income, Ministry of Health, and the like. However, if you were arguing for an increase in Student Allowance from 200 weeks to 250 weeks (i.e., you, as a university student, may believe that university students need more time to complete a degree), you may find an audience of Otago students more receptive to the increase than an audience more representative of the general population (even though you are also part of that general population), such as those who have no desire to attend university, those who believe that people should work before entering university so that they can self-fund their study, or those who may believe in less governmental support for those in need.

Political persuasion: while easily ascertaining someone’s political persuasion can be tricky, knowing whether an audience leans right (conservative), left (liberal), or somewhere in between (moderate) can help you to understand what an audience values. While the left/right way of discussing socio-political ideologies can overly simplify complex issues, it provides a reasonably helpful spectrum: there are people who tend to value social or fiscal conservatism and others who tend to value social equality. Those tendencies might affect emotional reactions to examples or points of view.

Consider the 2024 National (generally considered to be right-leaning) coalition governmental decision to exclude the social sciences and humanities from the large Marsden research funds pool in favour of sciences. (At the time of the announcement, the Marsden Fund invested in “excellent, investigator-led research aimed at generating new knowledge, with long-term benefit to New Zealand. It support[ed] excellent research projects that advance[d] and expand[ed] the knowledge base and contribute[d] to the development of people with advanced skills in New Zealand. The research [was] not subject to government’s socio-economic priorities” (Royal Society 2017)). In her 4 December 2024 announcement, the Minister of Science, Innovation, and Technology, the Hon. Judith Collins (National), stated, “The focus of the Fund will shift to core science, with the humanities and social sciences panels disbanded and no longer supported. Real impact on our economy will come from areas such as physics, chemistry, maths, engineering and biomedical sciences” (New Zealand Government 2024). Note the emphasis of Collins’s statement (“real impact”) and where it falls (“economy”). For that government, the impact of research with “long-term benefits” seems to be measured in monetary terms, and so disciplines that may measure value in other aspects of well-being (Languages; Social and Community Work; Literature; History; Gender Studies; Media, Film, and Communication; etc.) were excluded from funding.

Identifying such socio-economic factors will help you to frame your argument in a way that makes sense to your audience. Remember that you are not trying to persuade yourself. You already know your point of view or what you want. Persuasion is the communicative act of trying to get someone to agree with your point of view or to act in a certain way, and to do so well requires that you consider who your audience is and what they may already think and believe about the matter at hand, as well as how they might be most likely to react to your text. That consideration then informs your choice of persuasive methods.

Exploring a Text: Ethos, Pathos, Logos

The Denver Nuggets won the 2023 NBA championship, and its star player, Nikola Jokic, was named MVP. Have a look at the NBA’s tweet and subsequent responses:

Take a moment to consider why the NBA might post an image of one of its marquee players holding a baby while receiving the trophy rather than post an image of him playing basketball. Do the subsequent responses suggest at least part of the rhetorical effect of that tweet?

The responses vary noticeably in content and (intentionally or not) their own rhetorical strategies; those rhetorical strategies might affect our perceptions of that content. Think about Chri$’s response. It has plenty of stylistic elements that do not conform standard written English:

- “jokic” is a proper noun and also the first word in the sentence, so it should have a capital.

- “jokic” should also be a possessive (i.e., Jokic’s ring), but it doesn’t have the apostrophe and the s.

- The response seems to comprise two sentences–the first sentence stopping between “career” and “dude”.

Do these stylistic elements matter here? Of course, tweets and academic essays are different genres, and readers will have different expectations of language and content. Perhaps Chri$’s response simply follows the conventions of Twitter (now X).

But, look at the Chri$’s response in its context: the other four responses are punctuated more fully, having at least one full stop. Chri$’s stylistic choices might affect how we read his message–even among other tweets. Perhaps the writing style reveals something about Chri$’s culture, education, or outlook towards the topic or the reader. For example, can we take the statement about Jokic’s struggles at face value: is his claim sarcastic, or should we question the claim’s logic based on the other stylistic elements?

Look at Steph’s approach, “Tooooooooo Brate!”. The exclamation point suggests excitement (i.e. tone and emotion), but why choose Serbian (“To brate” is something like “That’s it, bro”) among other replies that are in English? The answer might be as simple as Steph speaks Serbian, and she is replying in a language with which she is comfortable. It might help us to know that Jokic is also Serbian. Steph’s language choice could relate to ethos. By using the language of the person it’s recognizing, Steph’s response might seem more credible or genuine. It may also simply align Steph more closely with Jokic.

Bertina does not start with congratulations. Rather, her response reacts to the child in the NBA’s photo–perhaps trying to elicit emotions. Many people find “little ones” to be cute, vulnerable, and endearing, plus they have relatively big eyes, which research has shown appeals to us. Why–in a thread about the MVP–would Bertina mention the child before the MVP himself? Intentionally or not, the choice suggests priorities (ethos) and potentially stirs the emotions of the reader (pathos). It also suggests that the NBA’s choice of image resonated with at least some segment of their audience.

Yoav Rimon’s reply also illustrates ethos. It mentions Novak Djokovic by name alongside Jokic, but specifies only vaguely why it does so. This choice works only if others recognize the person to whom Rimon refers. It establishes Rimon’s ethos with a sports-minded audience: Rimon knows that both Djokovic and Jokic are Serbian sport stars (general international sport knowledge) and suggests that he knows Djokovic won tennis’s French Open only a few days before Jokic won basketball’s MVP (up-to-date and wide-ranging sport knowledge). The reply would also have a potentially emotional effect for Serbians (pride). Rimon is using a thread congratulating Jokic to recognize Serbian sports figures in general.

The point is that stylistic choices (such as lack of punctuation), word choices (“brate” instead of “brother”), organization (Jokic’s child before Jokic), and content itself (Djokovic and Jokic in the reply) can all affect how our messages will be received. We need to consider our rhetorical moves carefully.

Exploring Persuasive Moves

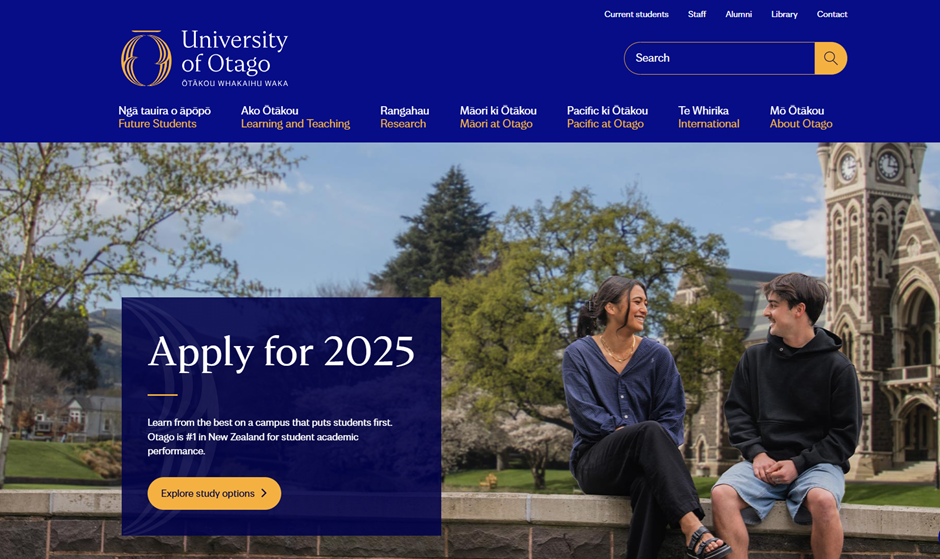

My main point is that texts rarely provide information in a neutral way. The creators of texts control (purposefully or inadvertently) the rhetorical moves put into service of achieving their own goals (whether they are clear on those goals or not). To further illustrate this control and examine how persuasion works in a text with which you are already familiar, let’s consider the rhetorical moves on the University of Otago’s landing page:

You (as a student) and I (as a staff member) likely use this website routinely for all sorts of reasons: searching our library’s articles and books; accessing our learning management software; checking important dates such as the beginning of semester, the length of study break, or the exam period; checking final grades in papers; and so on. But, look at that familiar landing page again, this time with fresh eyes: is the Otago landing page designed for us (by which I mean, are we its intended audience)? And what do you think the page’s creators are trying to achieve (what’s their goal)?

When you look at the landing page now, you might notice that this text initially offers us relatively little real estate. Up in the right-hand corner, we can indeed find links for “Staff” (me) and “Current Students” (you). There are other links in the top menu bar for “Learning and Teaching” or “Māori at Otago” or “International” (each of which offer further information for students currently enrolled at Otago), but the majority of space on the webpage seems to prioritize another goal: acquiring new students. What signs are there that this text’s authors have this goal and what means do they use to achieve that goal (persuasion)?

The most prominent writing on the page–while brief–tells us a lot. “Apply for 2025” is the largest of all phrases on the screen. It’s larger than even the name of our institution. In the wording immediately below “Apply for 2025”, the University chooses to describe itself. It could choose to describe itself in any number of ways, but the words of this landing page seem to have prospective students in mind: “Learn from the best on a campus that puts students first.” These words carry ethical and emotional appeals: we are worthy to listen to and study with (ethos), and you will be cared for (pathos). The next sentence offers some evidence (logos) while plying further ethical (we know what we are doing: join us!) and emotional (pride: you can be among the best in your country!) appeals: “Otago is #1 in New Zealand for student academic performance.”

The biggest element of the landing page by far, though, is the image. Any image could have gone here, so consider the choice of this image carefully. Look at the weather captured in the photo: do you prefer sunny days or overcast or rainy days? Certainly, Dunedin has some beautiful weather, but the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) also reports that for Otago, “Hours of bright sunshine average about 1600 hours annually and are often affected by low coastal cloud or by high cloud in foehn wind conditions” (NIWA 2024) –fewer hours of bright sunshine than most other university cities in the country. You may also notice further clues that indicate warmth: one of the students in the image is wearing open-toed shoes while the other is in shorts; some trees are blossoming in the background. Do you prefer being warm to cool?

Note, too, the buildings. The main building in clear focus is the University’s most iconic one. As a student here, how many classes do you have in it? I can confidently respond to that question with the same answer for everyone reading this text: zero. It isn’t a teaching building. What is the purpose, then, in placing it in an image to attract potential students? Does it suggest the strength of tradition? After all, it’s one of the University’s oldest buildings, perhaps reminding viewers that Otago is New Zealand’s oldest university. Or, it may simply be an aesthetic choice: are all buildings on campus equally beautiful?

The image could also signify some other underlying assumptions about what its intended audience (perspective students) values. The students appear to be happily chatting: what are they chatting about, do you think? It’s of note that no textbooks or electronic devices appear in the image that would suggest academic work. Maybe the two young people are indeed chatting about how enthralling the morning’s lecture was; the time on the clock seems to be either 12:00 or 3:00 p.m. (maybe that lecture wasn’t so early after all?). The students are also facing each other in relatively close proximity without looking at their phones; is the right foot of the student on the left brushing the left leg of the student on the right (connection!)? While one cannot be sure of gender identities by sight (either student could identify as male, female, or gender diverse), the image includes two students that both seem to conform to fairly traditional gender presentations. That is, why have an image with one (seemingly) female student sitting close to one (seemingly) male student? Why not two (or more) females or two (or more) males?

My point is that the creators of this text had practically limitless choices in selecting the words and images that they used to create the text. It is possible that the website creators (likely in the marketing and communications office of Otago) chose the words and images we see without giving them much thought, but it’s much more likely that the words and images we see are based on careful selection to achieve a goal (attracting students to apply and attend the university). Moreover, to achieve that goal, they likely made some assumptions about what their intended audience might value in order to appeal to those values and priorities.

Exercises

Imagine that you are in the marketing and communication office at Otago and that you have been tasked with changing the landing page to appeal to a different audience for a different purpose. What image and writing might you choose for the following:

| Audience | Goal |

| Parents of second-year students already at Otago | To accept an increase in fees of 25% |

| First-year students already studying at Otago | To drink responsibly |

| Lecturers at Otago | To retire early |

Truthiness

You may harbour some skepticism of my reading of that landing page–maybe you think I’m pushing the overall argument too far (Great! One of our graduate goals is critical thinking), even if some parts of my reading seem to be accurate. But, if I really want to convince you of my point of view (that the rhetorical choices of the landing page are purposeful and are pointed at a particular audience, making assumptions about that audience in order to persuade), I need to provide evidence rather than relying on truthiness. In other words, I need to increase my pile of apples.

Truthiness is a term coined by American comedian Stephen Colbert in 2005 to denote the seeming truthfulness of a statement–a statement that is taken as true not because of the evidence given by the speaker but because of the feeling the statement engenders in the listener or the general desire for the statement to be true. Truthiness comes “from the gut”, not from weighing up sometimes competing or inconclusive facts in a logical manner.

Earlier, I intimated that the University’s image containing one (seemingly) female student sitting close to one (seemingly) male student seems rather purposefully suggestive. I could point to the nature of the photo itself for support: the photo is unlikely to have been a spontaneous selfie that just so happened to end up on the landing page (i.e., neither student is holding a phone or selfie stick, there is no one else in the photo, the photo has the focus precisely on the students, the Clock Tower is easily visible, etc.), and so composition was a factor when the photo was taken. However, without interviewing the photographer or the people who subsequently selected the image for the landing page, I could point to Otago’s “Quick Statistics” page where a five-year trend shows that those who identify as female routinely outnumber those who identify as male at roughly three to two:

While these numbers span five years (more apples!) and might suggest that the image depicts a paradigm that doesn’t seem to represent the student demographics accurately, the numbers by no means prove the rhetorical moves of the text. The numbers might simply suggest that whoever chose the image didn’t care about representing the student population accurately. What, then, did they care about? We still need more apples.

There can always be more apples, so sometimes you need to rely on your audience to fill in some apple-shaped gaps, as I am doing here. I’ve shown you the University’s landing page and provided evidence that someone at the University seems to have designed it primarily to persuade new students to attend Otago rather than to support existing students or staff (though the website still does have that functionality): the size, placement, and content of the chosen text and image are easily verifiable by you. I have given examples to support my point that its creators’ most prominent words speak to the call for new students, to the University’s credibility as an educational institution, and to its pastoral care (i.e., new students will get a quality education and that they will be well looked after). I’ve also noted that the most prominent text (i.e., the main image) suggests a reasonably warm climate and beautiful environment (there are indicators that seem to support such a conclusion: blue sky and warm-weather clothing). Which leaves the choice of people in the image that don’t seem to accurately represent Otago demographics: aside from education and comfort, what other activities might be part of one’s university experience?

So, the final word on persuasion goes to brevity. People don’t always make decisions logically or even evaluate evidence; they take shortcuts and gravitate towards what they already know or believe they know. And, if you know your audience’s ethical, emotional, or logical stances on a topic, you can account for those positions to determine what you need to include and what you can elide.

But, let’s also turn the idea of truthiness towards how you will be perceived by your audience (ethos). When you are trying to persuade, have you relied on actual evidence or on what you simply believe? If you have relied on evidence (great first steps!), who created/supplied that evidence (ethos), how will your audience react to that evidence (pathos), and have you provided enough evidence (logos)? If you have relied on what you already believe without evaluating that belief (truthiness), what is the impetus for your audience to share that belief? When you attempt to persuade your audience to your point of view or to act in a certain way, you need to gauge how much information to provide based on what you believe your audience will already know, hold beliefs about, or surmise. Doing so not only increases the chance that you will be able to persuade your listeners and readers to hear and see things your way, but it will also hone your own position in beneficial and constructive ways.

Works Cited

Aristotle. 1924. The Works of Aristotle: Rhetorica. Ed. and Trans. Rhys Roberts. Oxford: Clarendon.

Buchanan, Findlay. 2022. “New Zealand’s Cats Are Decimating Native Wildlife – Should They Be Treated as Pests?” The Guardian. 7 April 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/07/new-zealands-cats-are-decimating-native-wildlife-should-they-be-treated-as-pests.

The Department of Conservation. 2024. Predator Response: Protecting Native Species 2024/25. Wellington. https://www.doc.govt.nz/globalassets/documents/our-work/national-predator-control-programme/predator-response-booklet.pdf.

National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. 2024. “Map South.” https://niwa.co.nz/map-south.

New Zealand Government. 2024. “Marsden Fund Refocused For Science With A Purpose.” 4 December 2024. https://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/PA2412/S00039/marsden-fund-refocused-for-science-with-a-purpose.htm.

The Royal Society of New Zealand. 2017. “Marsden Fund: Terms of Reference 2017.” https://www.royalsociety.org.nz/assets/Uploads/2017-Marsden-Fund-Terms-of-Reference-RF-style.pdf.

University of Otago. 2024. “Quick Statistics.” https://www.otago.ac.nz/about/quickstats.

Media Attributions

- Get Greeting Say Hi © mojitok

- Clowns Hi gif © Tenor.com

- Apple, green © Toni Cuenca is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Apple-green-diet is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Green-214133_1280 © Julenka, made available umder the Pixabay free licence

- Nice Green Apples © ProjectManhattan is licensed under a Public Domain license

- © Rhododendrites is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Private: NBA tweet about Nikola Jokic being the MVP (copied under fair dealing for criticism and review) © NBA official twitter is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Private: Jokic tweet responses (copied under fair dealing for criticism and review) © The official NBA Twitter account and other Twitter users is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Otago-Landing-Page is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Otago Gender Statistics © University of Otago website is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

The communicative act of swaying someone to agree with your point of view or to act in a certain way

An impugning statement against the person rather than against the position that they hold