4 An introduction to open licensing and the public domain

Learning outcomes

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify open licences and define the public domain

- Understand and implement the Creative Commons licences

Open licensing

What is an open licence?

A licence is a document that specifies what can and cannot be done with a work – whether sound, text, image or multimedia. It grants permissions and states restrictions. Broadly speaking, an open license is one which grants permission to access, re-use and redistribute a work with few or no restrictions (Open Knowledge Foundation, n.d.).

You can identify resources with an open licence by a notice that will be displayed with the work, stating which licence it has been released under, with a link to the licence. See figures 4.1-4.6 below.

The most widely used open licences are Creative Commons (CC). However, it is important to know that there are other types of open licences which you may come across. Some examples are open source software licences, such as the GNU General Public Licence. which can also be used for material. Also, bespoke open licences, such as those used by the stock photography platforms Unsplash and Pixabay. are other examples. In this book, we will be focusing on Creative Commons.

Figures 4.1-4.6: 1. A Guide to the Gothic by Jeanette A. Laredo, CC BY 4.0; 2. Department of Education Copyright Webpage by Commonwealth of Australia, CC BY 4.0; 3. Green cactus by rocky mountain during daytime by George Pagan III, Unsplash licence; 4. Cultural transmission of traditional songs in the Ryukyu Archipelago by Yuri Nishikawa and Yasuo Ihara, CC BY 4.0; 5. Elk Hunt – Montana by David Wipf, CC BY 2.0; 6. The essential role of music in education by Richard Gill, CC BY 3.0.

Creative Commons (CC)

Creative Commons is a nonprofit organisation that was founded in 2021. They publish a set of free, public licences that give everyone from individual creators to large companies and institutions a clear, standardised way to grant permission to others to use their work. Watch the following video to learn how Creative Commons (CC) licences work.

Watch: Creative Commons licence explained [5:32 mins]

Watch: Creative Commons licence explained [5:32 mins]

Note: Closed captions are available by clicking on the CC button in the video.

Reflect: Creative Commons licensing

Reflect: Creative Commons licensing

Licence design

CC licences function within copyright law, granting permissions for as long as the underlying copyright lasts or until the licence terms are violated. Although they’re legally enforceable, they have been designed in a way to make them accessible to non-lawyers.

The licences are built using a three-layer design (as shown in Figure 4.7):

- The legal code contains the “lawyer-readable” terms and conditions that are legally enforceable in court.

- The commons deeds are the web pages that summarise the legal code, laying out the key licence terms in so-called “human-readable” terms.

- The “machine readable” layer is a summary of the key freedoms granted and obligations imposed written into a format that applications, search engines, and other kinds of technology can understand. When this metadata is attached, CC licenced works are more discoverable.

Figure 4.7: Three Layers of License by Nathan Yergler and Alex Roberts, licensed under a CC BY 3.0 licence.

Licence elements

Creative Commons (CC) licences are made up of elements that tell users how the work can be used. There are four possible elements, which are outlined below:

|

BY – Attribution | Credit must be given to the creator. |

|

SA – Share Alike | Adaptations must be shared under the same terms. |

|

NC – Non-Commercial | Only non-commercial uses of the work are permitted. |

|

ND – No Derivatives | No derivatives or adaptations of the work are permitted. |

Table 4.1: Licence elements by University of Melbourne Library, licensed under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence.

Sometimes people can be confused about what a non-commercial use or an adaptation is. These are explored in more detail below.

Non-Commercial

The legal code of the licence defines a non-commercial purpose as one that is “not primarily intended for or directed towards commercial advantage or monetary compensation”. Note that the definition depends on the use, not the user. Visit the CC NonCommercial Interpretation page for more information and examples.

Adaptations

The no derivatives element prevents adaptations and the share-alike element requires adaptations to be shared under the same licence. What constitutes an adaptation is dependent on the applicable copyright law. In Australia, adaptations include creating a movie based on a book, translating a book into another language, and arranging music. The legal code of the licence also defines some specific uses as either adaptations or not.

While it can be tricky to determine exactly what is and is not an adaption, the following handy rules can help:

- Technical format shifting is NOT an adaption, e.g. digital to physical format

- Fixing minor problems with spelling or punctuation is NOT an adaption

- Syncing a musical work with a moving image IS an adaption

- Reproducing and putting works together into a collection is NOT an adaption, e.g., combining articles into an open textbook

- Including an image in a book, blog post, powerpoint, or an article, is NOT an adaptation unless the image itself is adapted.

Licence types

There is no single CC licence. The licence elements – BY, SA, NC, ND – can be combined to make up six different licences. This provides a range of options for creators who wish to share their works.

The six licences, from least to most restrictive in terms of the freedoms granted users, are:

|

The Attribution licence or “CC BY” allows people to use the work for any purpose (even commercially and even in modified form) as long as they give attribution to the creator. |

|

The Attribution-ShareAlike licence or “BY-SA” allows people to use the work for any purpose (even commercially and even in modified form), as long as they give attribution to the creator and make any adaptations they share with others available under the same or a compatible licence. |

|

The Attribution-NonCommercial licence or “BY-NC” allows people to use the work for non-commercial purposes only, and only as long as they give attribution to the creator. |

|

The Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike licence or “BY-NC-SA” allows people to use the work for noncommercial purposes only, and only as long as they give attribution to the creator and make any adaptations they share with others available under the same or a compatible licence. |

|

The Attribution-NoDerivatives licence or “BY-ND” allows people to use the unadapted work for any purpose (even commercially), as long as they give attribution to the creator. |

|

The Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence or “BY-NC-ND” is the most restrictive license. It allows people to use the unadapted work for noncommercial purposes only, and only as long as they give attribution to the licensor. |

Table 4.2: Creative Commons licence types

Public domain

There’s a common misconception that everything freely available online is in the public domain – and sometimes the term is used interchangeably with public sphere to refer to publicly available knowledge or public discourse. However, when it comes to copyright, public domain means something very specific.

Material is in the public domain when no one holds copyright, and therefore, there are no copyright restrictions on how the material can be used. There are two main ways material enters the public domain: via copyright expiry or the CC0 Public Domain Dedication.

Copyright expiry

Copyright lasts a long time, but not forever. In Australia, copyright typically expires 70 years after the death of the creator, while in Aotearoa New Zealand it’s currently 50 years after death. However, duration can vary depending on factors such as the type of material and copyright owner. Amendments to copyright law also mean that it can be difficult to determine if material has expired.

You can visit the following resources to help determine if copyright has expired in material:

- Australia: Duration of copyright and Copyright term flow charts by the Australian Libraries and Archives Copyright Coalition

- Aotearoa New Zealand: Duration of copyright by the New Zealand Intellectual Property Office

While there is no central register of material in the public domain, Creative Commons has created a Public Domain Mark. This can be used to clearly indicate when something is in the public domain due to copyright having expired (or never been applicable).

|

The Public Domain Mark indicates that there is no known copyright in any jurisdiction. |

Table 4.3: Public domain mark

It should be noted that most public domain material does not have this mark and you’ll need to determine for yourself if copyright has expired in your jurisdiction. One reason for the limited use of the mark is that it’s only meant to be applied to material which is in the public domain everywhere in the world, which is a high standard to prove.

CC0 Public Domain Dedication

While copyright expiry was traditionally the main way material entered the public domain it is now also possible for creators to dedicate their material to the public domain.

Creators who want to take a “no rights reserved” approach and disclaim copyright entirely can use the Creative Commons public domain dedication tool (CC0). This is different from the CC licences discussed in the last section as CC0 material has absolutely no conditions attached, you don’t even need to provide an attribution.

|

The CC0 Public Domain Dedication indicates that the creator has waived all of their rights to the work worldwide under copyright law. |

Table 4.4: CC0 public domain dedication

Using openly licensed and public domain material in practice

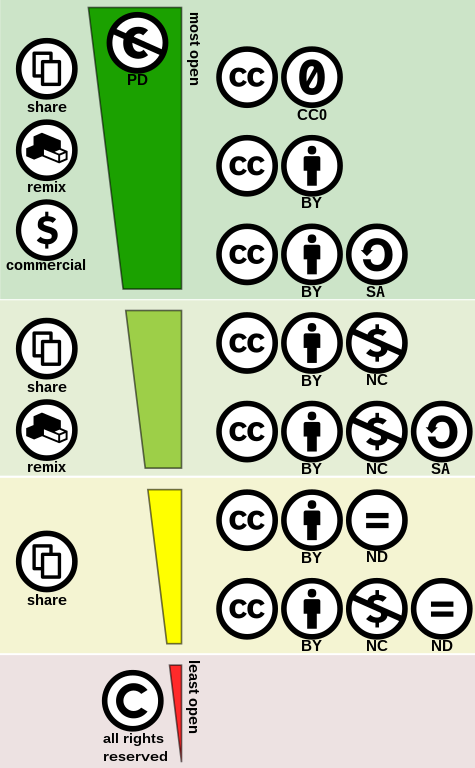

Having read about the public domain and different CC licences, you now understand that some options are more open than others. The infographic below shows the spectrum of openness from the most to least open options

Figure 4.8: Creative Commons license spectrum by Shaddim, licensed under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

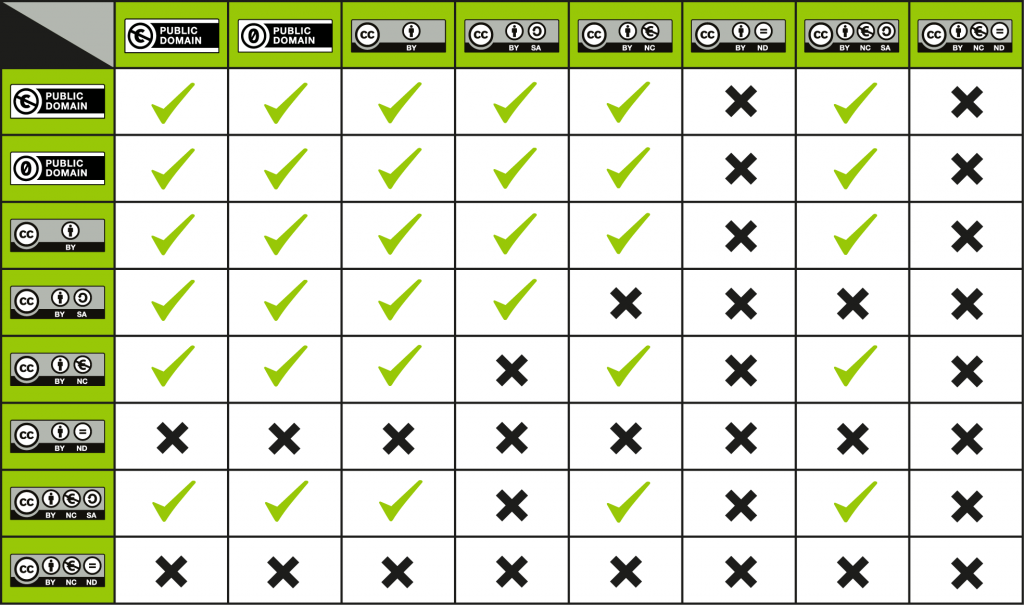

Compatibility of licences

In an ideal world, you would always be able to find resources with the most open licences. However, you’ll be more likely dealing with resources with different licences. This can be complicated as not all CC licences are compatible. For example, you cannot create a remix using works with a CC BY-SA licence, and a CC BY-NC-SA licence since both require the remixed work to be released under the same licence. The following chart can be used to help determine if resources with different licences are compatible.

Figure 4.9: CC License Compatibility Chart by Kennisland, licensed under CC0

For more information about licence compatibility, see the Combining and adapting CC material FAQs.

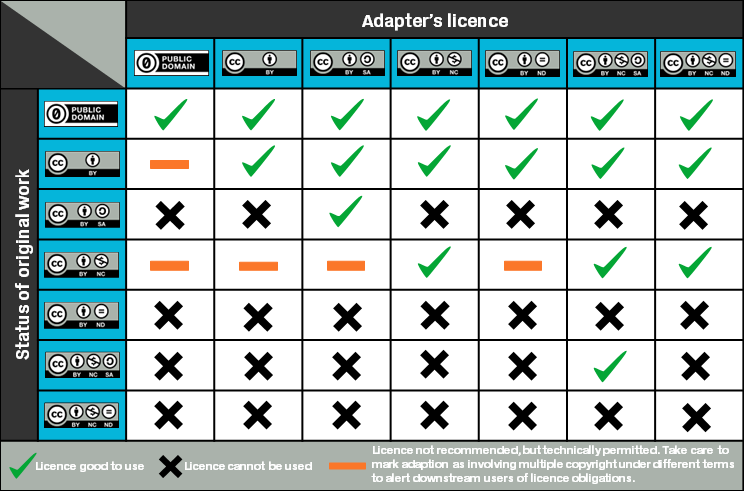

Licensing adaptations

How the original resources are licensed also affect what licence can be applied to a remix. CC refers to this as the adapter’s licence. There are a number of factors to consider, but CC recommends choosing the more restrictive of the original licences for the adapter’s licence. This is because it eases reuse for downstream users. The following chart can be used to select an adapters licence.

Figure 4.10: CC Adapter’s Licence Chart adapted from Creative Commons, licensed under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

Figure 4.10: CC Adapter’s Licence Chart adapted from Creative Commons, licensed under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

Copyright, the public domain, and open licensing are integral concepts related to OER. This is because copyright automatically applies to teaching and learning materials and typically prevents the 5Rs from being exercised. Specifically, copyright prohibits unauthorised:

- copying, which prevents the right to retain,

- public performance, which prevents the right to reuse,

- adaptations, which prevents the right to revise and remix,

- publication, which prevents the right to redistribute; and

- communication, which also prevents the right to redistribute.

In order for these rights to be allowed, material must be in the public domain or openly licensed. Even with an open licence, the conditions of certain licences may prevent some uses. It’s therefore important that librarians have a good understanding of copyright and open licences if they are to lead or contribute to open education initiatives. With this knowledge you will be able to:

- find material with an open licence,

- identify material in the public domain,

- interpret and apply licence conditions; and

- explain to others how public domain and openly licensed material can be used.

Reflect: Think about copyright and open licensing within your university context.

Reflect: Think about copyright and open licensing within your university context.

- Can you think of a situation in which you would need some basic understanding of copyright and open licensing in relation to your OER practice?

- How would you approach a complicated copyright or open licensing question which you didn’t feel confident answering? What resources do you have at your disposal to help, e.g. internal/external information resources and/or experts?

- When advising others on how they can use openly licensed resources, what would you need to consider?

Do: Copyright and open licensing quiz

This quiz will test your understanding of copyright, the public domain, and open licences in relation to open educational resources. Completing it will provide you with an opportunity to demonstrate your knowledge and identify any areas which may require review or clarification.

Read: Why, oh why, CC-BY?

Read: Why, oh why, CC-BY?

This blog post outlines the experience of one librarian’s decision to apply Creative Commons licences to her scholarly output.

Reflect: Switching licences

Reflect: Switching licences

Key takeaways

In this chapter we learnt that:

- Copyright automatically restricts how material can be used and generally inhibits the 5Rs.

- Material in the public domain can be used without restriction.

- Material can enter the public domain either through copyright expiry or dedication.

- Copyright owners can apply an open licence to material.

- An open licence grants permission to use the material in certain ways along with any limitations and conditions.

- Some open licences are more open than others, with the most open license being CC BY and the most restrictive one being CC BY-NC-ND.

- The licence type dictates if resources can be remixed together, and what licence can be applied to adaptions.

Next chapter, we will discuss other ways you may be able to use material which isn’t in the public domain or openly licensed. We’ll also explore the concept of attribution in more detail.

References

- Australian Libraries and Archives Copyright Coalition (n.d.). Duration of copyright. Retrieved July 28, 2022 from https://alacc.org.au/duration-of-copyright/

- Creative Commons. (2021). Creative Commons Certificate for Educators, Academic Librarians and GLAM. Retrieved July 28, 2022 from https://certificates.creativecommons.org/cccertedu/

- New Zealand Intellectual Property Office. (n.d.). Duration of copyright. Retrieved July 28, 2022 from https://www.iponz.govt.nz/about-ip/copyright/duration/

- Open Knowledge Foundation. (n.d.). Open definition. Retrieved July 28, 2022 from https://opendefinition.org/guide/

- University of Melbourne. (2022). Introduction to Open Educational Resources (OERs): A professional development program for Scholarly Services staff. Retrieved November 30, 2022 from https://melbourne.figshare.com/articles/educational_resource/Introduction_to_Open_Educational_Resources_OERs_A_professional_development_program_for_Scholarly_Services_staff/21060673

Copyright

This module has been adapted in part from:

- Module 1: What are OERs from Introduction to Open Educational Resources (OERs): A professional development program for Scholarly Services staff by Zachary Kendal & Amy Perkins, University of Melbourne Library, licensed under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

- Creative Commons Certificate for Educators, Academic Librarians and GLAM by Creative Commons, licensed under a CC BY 4.0 licence

- Open definition by Open Knowledge Foundation, licensed under a CC BY 4.0 licence

- Find Open Content by OER Africa, licensed under a CC BY 4.0 licence