5 Attribution and using copyright material in OER

Learning outcomes

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Inform others of the basics of copyright in relation to open education

- Provide attributions appropriate for a range of resources and uses

Using copyright material in OER

Material which isn’t in the public domain or openly licensed is not recommended to be used in OER. This is fundamentally because it doesn’t meet the definition of an OER and copyright impacts the right to retain, reuse, revise, remix, and redistribute. That said, there are occasions where it may be necessary to use copyright material[1]. For example, if you are working on an open textbook and need to include unique copyright material to explain a concept. This could be a quote from a literary work, an image from a seminal research paper, or an excerpt from a video.

Using copyright material in OER raises a number of issues. First of all it can only be used when it is legally allowed. This can be difficult to determine and take up a significant amount of time. The three strategies which may allow copyright material to be used are:

- Copyright exceptions

- Linking/embedding

- Permissions

These three strategies will be discussed in more detail later in this section.

Even when the use is legal, the copyright material will need to be carved out from the open licence that is applied to the OER. It’s therefore important that the copyright material is clearly identified and that the open licence statement explicitly states that it is excluded. When different conditions are applied to separate components of an OER it makes it difficult for users to fully exercise the 5Rs. For this reason, it’s preferable to avoid using copyright material wherever possible. Alternative public domain or openly licensed material can often be found, or material can be created from scratch.

Copyright exceptions

Both Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand copyright law contain exceptions that allow material to be used in specific circumstances. Unfortunately, most exceptions contain limitations that typically make them incompatible with OER. For example, under “fair dealing for research or study”, a person may be able to copy something for their own use, but they cannot share it with others. This means that the exception cannot be used since sharing is the most fundamental aspect of an OER.

In comparison, “fair dealing for criticism or review” and “fair dealing for parody or satire”, doesn’t prevent the new material from being shared. However, universities have different approaches to Fair Dealing exceptions. If your university approves of such use, include a disclaimer/note in your OER indicating that Fair Dealing has been applied to xx items and that they are excluded from the open licence of the OER.

If you’re working on an OER project you should check what approach your university has adopted around exceptions and seek advice from your university copyright officer if you plan to rely on them.

Linking/embedding

If the material is available online you can choose not to exercise any copyright rights by providing a link, or possibly embedding it directly in your OER.

When you provide a link, people are directed to visit the original site where the material is hosted – no copy is made. You still need to be careful when providing links and avoid linking to:

- Illegitimate material: this is material which has been made available online without the copyright owner’s permission.

- Material behind a paywall: this includes library subscription databases. While this is common practice within universities, it is important to remember that OER are not limited to an institutional cohort, so anyone outside of the subscribed institution won’t have access to the linked material.

- Material with other login requirements: even if there is no cost involved in creating an account, you should consider the privacy of users and if they will need to give up personal information to access the material.

- Unprofessional sites: such as sites with an overwhelming amount of pop-up ads.

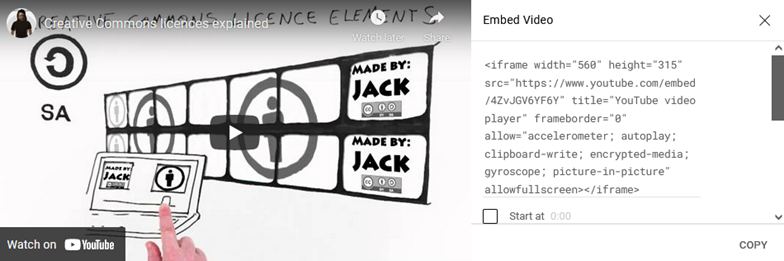

Embedding is like linking in that no copy is made, but users do not need to separately visit the site where the material is hosted. This is done by copying the embed code, usually symbolised as < >, and pasting it into the html of a page (see Figure 5.1). The code does not create a copy, but allows the material to be viewed within the resource. You need to be careful when embedding. The material needs to be legitimate and you should only embed material when the hosting site enables it to be embedded. For example, YouTube allows videos on their platform to be embedded on other sites by providing the code for this under the “share” options.

Figure: 5.1: Code from YouTube which was copied to embed the Creative Commons licences explained video by Process Arts, licensed under a CC BY 3.0 NZ licence, which was used in the previous chapter.

Permissions

You will need to seek permission from the copyright holder if you want to use copyright material in an OER and can’t rely on an exception and are unable to link to it. You’ll also need permission to use openly licensed materials if they have incompatible licences, e.g. combining CC BY-SA and CC BY-NC materials, or if your use falls outside the licence scope, e.g. adapting CC BY-ND material.

Firstly, check the copyright status and terms and conditions of the material. Many people and companies set out the terms relating to permission to use their copyright material on the site itself. This usually happens in one of three ways:

1. The material itself may contain information on its permitted uses (there may be an indication near where the content is posted).

Figure 5.2: Screenshot of NGV website showing collection image and text which appears when the “Download” link is clicked, used under the terms as indicated.

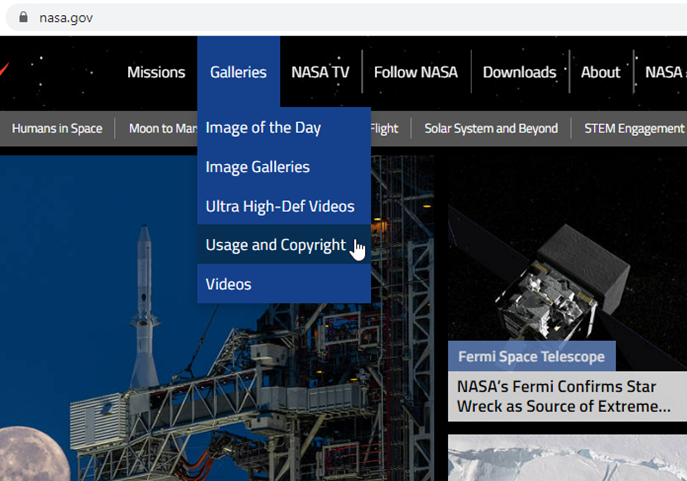

2. A section of the website entitled ‘Copyright’, ‘permissions’ or similar will contain copyright and permissions information for material on the site.

Figure 5.3: Screenshot of NASA website showing link to Usage and Copyright page, used under permission as outlined on the page.

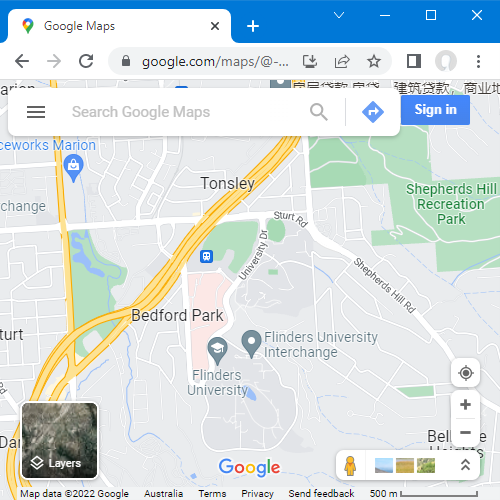

3. The site’s terms and conditions of use will specify how material can be used

Figure 5.4: Screenshot of Google Maps showing link to Terms at bottom of the page, used under terms outlined on the page and the additional Using Google Maps, Google Earth, and Street View permissions page.

If you want to use copyright material in your OER, in a way that is beyond the conditions of the express licence, then you will need to contact the copyright owner for further permission. You’ll need to seek permission in writing and outline how you plan to use the material, where your OER will be hosted, and the type of Creative Commons licence it will have.

Attribution

Even when you can legally use a resource, it is important that you acknowledge the work of others. This is a legal moral right and an important academic integrity principle. It is also a cornerstone condition of open licenses. An attribution statement provides credit to the original creator and is a legal requirement of an open licence.

Attribution vs. citation

You are probably already familiar with the concept of citation. A citation allows authors to provide the source of any quotations, ideas, and information that they include in their own work based on the copyrighted work of other authors. An attribution is similar to a citation, but there are also differences. These are summarised in Table 5.1 below:

| Citation | Attribution |

| Purpose is academic (e.g., avoiding plagiarism) | Purpose is legal (e.g., following licensing conditions) |

| Does NOT typically include licensing information for the work | Includes licensing information for the work |

| Can paraphrase, but cannot typically change the work’s meaning | Can typically change the work (e.g., advanced permission granted with licence) |

| Many citation styles are available (e.g., APA, Chicago, and MLA) | Attribution statement styles are still emerging, but there are some defined best practices |

| Cited resources are typically placed in a reference list | Attribution statements are typically found near the work used (e.g., below an image) |

Table 5.1: Attribution vs Citation adapted from Abbey Elder (adapted from Citation vs. Attribution by Laura Aesoph). All tables licensed CC BY 4.0

Attribution statements

There is no one correct way to provide an attribution statement, but the best practice is to include the full TASL information for the resource. TASL is:

- T = Title

- A = Author (creator)

- S = Source (link to the resource)

- L = Licence (link to licence deed)

If you don’t have all of the TASL information about the resource, do the best you can and include as much detail as possible in the attribution statement.

The attribution statement under Figure 5.5 is a good example of a statement as it includes all of the TASL information with appropriate links provided, where:

- Title is “Creative Commons 10th Birthday Celebration San Francisco”

- Author (creator) is “tvol” hyperlinked to his profile page

- Source is “Creative Commons 10th Birthday Celebration San Francisco” hyperlinked to original Flickr page

- Licence is CC BY 2.0 hyperlinked to licence deed

Figure 5.5: Creative Commons 10th Birthday Celebration San Francisco by tvol, licensed under CC BY 2.0.

When a work is adapted, changes need to be indicated in the attribution statement along with the creator of the original work. An example is demonstrated in the statement for Figure 5.6 below:

Figure 5.6: This work, “90fied”, is a derivative of “Creative Commons 10th Birthday Celebration San Francisco” by tvol, used under CC BY “90fied” is licensed under CC BY by [Your name here].

Using Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property

Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) refers to the right of Indigenous Australians to protect their cultural heritage, including all aspects of art, knowledge systems, and culture (Janke, 2022). When planning to include Indigenous content in OER, it is important to be cognisant of ICIP and to respect the rights of Indigenous individuals and communities to be consulted and provide consent.

It is crucial to seek appropriate Indigenous permissions to use or disseminate Indigenous knowledge. The following sources provide guidance and information about Indigenous Protocols:

- The Australia Council for the Arts’ Protocols For Using First Nations Cultural And Intellectual Property In The Arts

- Oxfam Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cultural Protocols

- True Tracks, by Indigenous lawyer Terri Janke, provides information about the legal protection of Indigenous art, cultures and knowledge.

Be aware that Indigenous cultural IP may not fit into traditional areas of copyright and reuse. It’s best to seek out help from those who have expertise in this area. Contact your University’s Indigenous unit for more information.

Although there is a huge amount of openly licensed material available it’s likely that there’ll be times when you want to use copyright material. This means you need to know if and how this is legally possible. It’s also important that you can explain this to others. For example, academic staff may identify copyright material they want to use and are already familiar with the rules that allow them to do this in courses they typically teach. You’ll need to explain the reasons why these rules don’t apply to OER and to provide them with a solution.

Reflect: Misconceptions and differences

Reflect: Misconceptions and differences

There are many misconceptions about copyright and openly licensed material. For example, one misconception is that it’s legal to use 10% of copyright material for any purposes, as long as you credit the creator. Whereas the truth is that even using a small portion of copyright material may be an infringement depending on the circumstances.

- Identify one common misconception about copyright and/or openly licensing that you have encountered, and think about how you would address it.

- What do you see as the greatest difference between using openly licensed and copyright material?

Case study: Combining copyright and openly licensed material

Nikki Andersen is the Open Education Content Librarian at the University of Southern Queensland. It is her role to design and ensure the copyright compliance of open textbooks. When producing open textbooks, Nikki uses a copyright tracker to keep track of the copyright statuses of content within the text. It is her job to check the third-party content, apply for permissions, suggest alternative replacements, ensure compatibility of licences, and ensure correct attributions.

Do: Analyse the copyright details

Do: Analyse the copyright details

Read the licence and copyright metadata from the textbook How To Do Science, published by the University of Southern Queensland. Scroll through the first chapter Science and the Scientific Method, paying attention to the figure attributions and copyright note.

Reflect: How to Do Science

Reflect: How to Do Science

- Is this text an adaptation or original work?

- The book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 licence, which is one of the more restrictive CC licences. Why would the University of Southern Queensland select this licence? What would they have needed to consider when choosing the licence?

- Some of the figures used in the book have different CC licences. Do you see any problems with this?

- Read the ‘copyright disclaimer’ at the bottom of the book’s landing page. It lists content in which permission was sought. What implication does this have for others wishing to adapt or reuse the text?

Case study: Attribution

The importance of attribution was demonstrated in the following two court cases.

Court case one: Drauglis v. Kappa Map Group, LCC

This case from the United States concerned the use of the “Swain’s Lock” photograph by Art Drauglis. The photograph was posted on Flickr under a CC BY-SA 2.0 licence and subsequently used on the cover of an atlas published by Kappa Map Group.

Figure 5.7: Swain’s Lock by Art Drauglis, licensed under a CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

Drauglis argued the CC licence was violated in several ways:

- The use of his photograph as a cover of an atlas constituted a “derivative work” which therefore would have had to have been shared under a CC-BY-SA licence to be compliant.

- There was inadequate information about the CC licence in the text of the atlas.

- The attribution term was not met because attribution was not appropriate, as the credit for the photograph was on the back cover in small font while the image was on the front.

Drauglis was unsuccessful, with the court finding that:

- The use of the photograph on the cover did not constitute a “derivative work”. Because the atlas was published “in its entirety in unmodified form” it was a “collective work” rather than a “derivative work”, which is “a work based upon the Work”

- The inclusion of “CC BY-SA 2.0” was adequate information about the CC licence and a link or the text of the licence was not required. This is because the CC licence refers to a URI (Uniform Resource Identifier) which can either be a Uniform Resource Link (URL) or the Uniform Resource Name (URN), which in this case was CC BY-SA 2.0.

- Credit was appropriate when compared with the credits given to the maps included in the atlas.

Court case two: Gerlach vs. DVU

This case from Germany concerned the use of a photograph of politician Thilo Sarrazin by Nina Gerlach. The photograph was released under a CC BY-SA 3.0 licence and subsequently used on the website of the German political party, DVU, without any attribution statement.

Figure 5.8: Thilo Sarrazin am 3. Juli 2009 by Nina Gerlach, licensed under a CC BY-SA licence

Gerlach first sent a notice and takedown letter which the party ignored so then sought a preliminary injunction against the unauthorised publication of the picture. This was granted as the court found that the licence terms were breached which meant the licence could not be relied on to use the work.

Do: Knowledge check

Key takeaways

This week we learnt that.

- Relying on exceptions to use copyright material in OER is complex and institutions take different approaches.

- Copyright material can sometimes be linked to or embedded in OER.

- In some cases you may need to seek permission from the copyright owner to use copyright material.

- Any copyright material that is used in OER needs to be clearly identified and it can affect how the OER is licensed.

- All material (openly licensed and copyright) needs to be properly attributed, this is both a legal requirement and an important academic integrity principle.

In the next chapter, we will start on Part 3 which is all about finding and evaluating OER.

References

Janke, T. (2022). Indigenous cultural and intellectual property (ICIP). Terry Janke and Company. Retrieved August 24, 2022 from https://www.terrijanke.com.au/icip

Copyright

This module has been adapted in part from:

- Module 1: What are OERs from Introduction to Open Educational Resources (OERs): A professional development program for Scholarly Services staff by Zachary Kendal & Amy Perkins, University of Melbourne Library, licensed under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

- Creative Commons Certificate for Educators, Academic Librarians and GLAM by Creative Commons, licensed under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Drauglis v. Kappa Map Group, LLC from the CC Wiki Links to an external site., licensed under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Gerlach vs. DVU from the CC Wiki, licensed under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- The OER Starter Kit by Abbey Elder, licensed under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Self-Publishing Guide: A reference for writing and self-publishing an open textbook by Lauri M. Aesoph, licensed under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- In this chapter we refer to “copyright material” as material which has all rights reserved to distinguish it from “openly licensed material”. However, as you know from the previous chapter, openly licensed material is also protected by copyright but for the sake of brevity we will use these terms. ↵