Chapter 4: Essential skills

Liam Frost-Camilleri

Learning Objectives

- Understand the importance of essential academic skills: reading, note-taking, and time management.

- Develop strategies for effective and resilient academic reading.

- Explore what it is to make effective notes.

- Explore various time management techniques to enhance academic productivity.

- Cultivate personal habits that support academic success, including the development of reading resilience and self-efficacy.

There are some essential skills that you are expected to develop when you are studying a university course. This chapter focuses on three important ones: reading, note-taking, and time management. While there are other important skills to develop, they are beyond the scope of this textbook. The three skills discussed in this chapter, however, are essential for your academic success. Many aspects of these skills are quite personal, so experiment with what works for you and your situation.

4.1 Reading

Let us begin with the most commonly used essential skill at university: academic reading. Even if you are an experienced reader, you might find it difficult to navigate university texts. The reason these texts are so difficult is because everyday reading (the news, novels, social media etc.) is created to entertain, whereas higher education journal articles and textbooks are designed to inform and evaluate. So, unless you find these topics especially thrilling, the reading you must complete will test your ability to focus. One older but insightful piece of research on reading discusses the importance of building reading resilience, that is, the ability to read and interpret complex texts (Douglas et al., 2016). The research concluded that reading resilience can be developed when specific conditions are met. One of these conditions is close reading, which involves a careful examination of a text to uncover its deeper meanings and connections. This process requires analysing the text’s structure and overall message while engaging in critical thinking about its content. Therefore, close reading means actively engaging with the text, not just trying to memorise the content. To better engage with your texts, try the following strategies.

Reader voice

An effective strategy when reading academic texts is to develop a reader voice. A reader voice is like an inner dialogue that interacts about the text you are reading. The ‘voice’ you use might ask questions, reiterate what is being read, explain what you do not understand and/or generally comment on the reading. It is similar to what would happen if you went to the cinema and someone in the audience just kept talking about the film. Your thinking does not have to be said out loud, but if you keep asking questions, or even just vent your frustrations, you are, in fact, developing your reader voice. Try experimenting with this idea the next time you are reading something for your course or unit.

The purpose of reading

It is important to understand that starting a reading cold and without a central question or purpose can be extremely challenging. Before you begin, have an idea of the topic you are going to read about and even a couple of questions that you are trying to answer as this will help your focus. Being generally aware of the class requirements (assessments/class discussions) can also guide you toward the purpose of your reading. If you cannot finish this statement, “I am reading this to gain a better understanding of…”, then go back and review the assessment instructions or topic description.

Asking questions

The significance of questions is discussed above, but they are extremely important when you are learning to read academic texts. Having questions before you start reading keeps you focussed and will help you relate the content to your experiences and assessments. Most of the time your questions may be unanswerable, or you will simply end up with more questions, but this is the process of learning. Questions that spawn more questions are commonplace in academia, with most academics keeping important questions burning in their minds for years. Try not to underestimate the power of questions to boost your motivation and interest levels when reading and studying.

Previewing

Previewing is the process of understanding what the text is about before you start reading. Examine the headings, subheadings, pictures, and the structure of the text and make some conclusions about what it might explore. What questions might you be able to answer with this reading based on the information you have gathered?

Skimming

Skimming involves looking at small pieces of the text to find the themes and general ideas. As a starting point, many people will skim the abstract of an article to get a general sense of the themes. You could also read the first sentence of each section and look at any tables and graphs in the article. You may also wish to make a few notes while you do this, just to highlight the main points as you discover them. If you are skimming correctly, you should be able to tell if an article is suitable for your assessments at a glance. Try not to spend hours reading an article that you might not end up using.

Scanning

Scanning is used when you are looking for specific information. If you have a question to answer or you are looking for information that will help you complete an assessment, try scanning through while keeping in mind what you are trying to answer or find out.

Detailed reading

Detailed reading requires looking closely at the text and only occurs once you have decided that the text is useful to you. It is usually done while taking notes and summarising the main points. It takes time to do well, so try to be patient. During detailed reading, your reader voice will really start to develop. Ask questions about the text and maintain a dialogue with what you are reading. What is it telling you and how might you use it to aid your understanding and the completion of your assessments?

Developing a reading habit

If you are developing your ability to read academic texts for the first time, you have probably noticed how different it is. The language used is quite academic and can include vocabulary that you have never seen before. Developing a reading habit is the same as any other habit formation. If you can spend a little time on that habit each day you will find it much easier to develop and grow. Reading academic texts for 10-15 minutes a day is better than not reading them at all. It could be worth putting on a timer to keep track, or maybe you could measure your progress based on the number of pages read each day. Put that time aside and try to align it with a reward. Rewards might include a coffee with a friend, or watching your favourite show. Try to choose a reward that makes you feel like you have achieved something.

4.2 Reading a journal article

Once you receive your first journal article to read, you may be confused about where to start. Most readers of articles do not read them in a linear or straightforward way, and, because of this, it is worth knowing the anatomy of journal articles or papers.

Journal articles usually contain the following sections: abstract, introduction, literature review, methodology, discussion/results/findings, recommendations, and conclusion. While these are the main sections of most articles, you may also see other components, like hypothesis or case studies. These may be discipline-specific (a psychology article will offer a hypothesis for instance) and will be worth looking into as you become more familiar with journals.

Here is the aim for each section:

Abstract: The abstract is a short account of the article’s main points. It will discuss why the article was written, what questions the author(s) were looking to answer and provide a brief summary of what the main findings were. You should have a clear understanding of what the article is going to tell you by reading the abstract.

Introduction: The introduction sets the scene for the article and will usually give historical or general information about the topic being explored. After reading the introduction, you should have a good understanding of the relevant background knowledge of the study.

Literature review: The literature review covers the current research relevant to the article’s topic. In this section, the author(s) highlight the main arguments and points that researchers in the field have been making. This information is then used to build the case for the article that you are reading.

Methodology: The methodology discusses how the research was carried out, what ethics approval was obtained, what the research questions are, and the type of data collected and why. If it is a research project involving participants, the methodology explains who the participants were, what they were asked, and under what circumstances they were chosen. If the purpose of the article you are reading is to review current literature, it will detail how the articles were sourced in this section.

Discussion/results/findings: Depending on the research conducted and the expectations of the publishing journal, the discussion, results, and findings may either be presented together or separated. The discussion highlights the main points arising from the research. Sometimes this section contains subheadings that highlight the points, making it easier to follow. The results and findings section interprets the points made in the discussion. In the results/findings section, the author(s) refer to the content of the literature review to highlight how their article builds on the findings of previous researchers.

Recommendations: In the recommendations section the author(s) explain the limitations of the research and offer additional questions that may be answered next. The recommendations section might also be used to suggest changes in policy or workplaces based on the research findings.

Conclusion: The conclusion of an article summarises the main points with reference to the scene set by the introduction.

Understanding the anatomy of a journal article helps you make informed reading choices. While the abstract is a great place to start, readers who are familiar about the topic might skim the discussion or recommendations section to see if the article is worth reading closely. The methodology might be the last section to be read as it focusses on how the research was conducted and would not typically be quoted in a first-year university essay.

These are quite formal reading strategies that you can utilise, but there are other elements that could support your growth here too. Try to create the right conditions to help you read, such as good light, a relaxed room with no noise (if that is your preference), and perhaps a drink bottle to stay hydrated. Adjust your reading speed to see if you can better understand the text when reading slowly or quickly. Keep a record of relevant vocabulary that you find challenging so you can refer back to it often and enhance your understanding. Make sure you choose an appropriate time to read, especially if you find early mornings or evenings difficult times to focus. Highlight sections that you believe are important, and consider annotating the reading (that is, make notes on the reading to better explain it) to help capture your thinking. Above all, try not to let frustration get the better of you. If you are feeling frustrated, it is better to calm down before continuing to read. When it comes to reading (or learning in general), regulation before expectation is always key.

Practising reading strategy is the only way to become more proficient at it. Choose a complex academic text (e.g. a journal article or textbook chapter) and undertake a close reading. Annotate the text by identifying key arguments, evidence, and connections between ideas. Reflect on the deeper meanings you uncovered and how this analysis could inform your understanding of the content. It is also a good idea to discuss your reading with somebody else who has also done the reading to compare your understanding and adjust your approach.

4.3 Note-taking

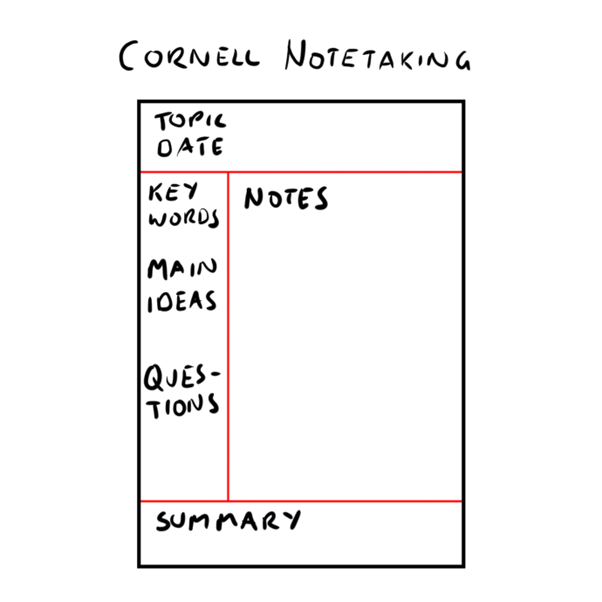

For many years the gold standard for note-taking has been the Cornell note-taking method. Professor Walter Pauk of Cornell University developed the Cornell method to make sure the notes taken by his students were fit for purpose. Before we explore what the Cornell method involves, it is useful to discuss the aim of note-taking.

Most students do one of two things when they take notes. They either write down everything from the PowerPoint and everything the lecturer says or they write down a few out-of-context lines for the entire class. Neither of these approaches fulfill the role of note-taking. The purpose of taking notes in class, or on a reading, is to clarify understanding and to have something to refer back to when you are studying or writing assessments. Notes are written for your future self to read. The notes you take in class will often be written in such a way that only you will understand them. This is why sharing notes with other students is generally ineffective. But what information should you be recording? This is where the Cornell note-taking method is useful.

The beauty of the Cornell method lies in its clearly defined spaces that detail what should be recorded. To begin, rule up your page so there is a top section, a bottom section and two rectangles in the centre, with the right rectangle wider than the left. The top section is reserved for the date, title or name of the lecture or bibliographic details of a reading. The right-hand rectangle is for detailed notes in your own words and the left rectangle is used to pull out the main ideas, keywords, or questions from those notes. Lastly, the bottom rectangle is used to summarise the entire page or lecture.

Again, this method works because the clearly defined spaces guide you on what to include. Using this note-taking system means you can always find important information when completing assessments or studying. Some students like to build on this method by adding different elements to help them review their notes later on. Getting creative in your note-taking is a terrific way to ensure that your notes are meaningful and easily followed.

Using symbols, mind maps, sketches, or pulling out important vocabulary that you are struggling with are all excellent ways of keeping your notes relevant and specific to your learning and experience. Note-taking is not an exact science, so try to experiment with it to see what feels right for you. Some students even develop a shorthand with different symbols and quick writing methods to make note-taking faster and more efficient. If you like to take a lot of notes, this could be a good option for you.

Learning Activity 4.2 Practise note-taking using the Cornell Method [PDF]

The best way for you to become more comfortable with note-taking is to practise. Choose a video that you would like to learn more about (TED talks are generally a good idea for this activity, as they are like lectures) and try taking notes using the traditional Cornell Method and then in a more creative way. Make notes on how these methods are different and how you might be able to develop your note-taking skills further.

4.4 Time management

Whenever we fail at something or wish to spend more time doing something in particular, we tend to scorn ourselves for not managing our time well. Developing your time management takes time, but there are elements you can focus on while you develop the skill. The research tells us that focusing on priority and being conscientious will lead to better time management, and it seems especially important for part-time students due to an increased need to manage competing priorities (MacCann et al., 2012). This suggests that managing our time is more about managing our space, being organised, and taking responsibility than it is about creating a schedule or sacrificing a weekend to study (although, those elements are still important). Another more recent study found a link between developing self-efficacy and time management. According to Bargmann and Kauffeld (2023), self-efficacy, or a belief in your abilities (revisit Chapter 2 for more clarity), is more important than time management when beginning university study. This importance flips once a student develops self-efficacy, with a time management strategy becoming crucial. Similarly, another study found that students only experienced poor time management when there were competing responsibilities, like work or family (Nieuwoudt & Pedler, 2023). For this reason, it is better to first focus on what is happening around your study time rather than the studying itself.

Hopefully after reading the first few chapters of this book, you are beginning to better understand who you are as a learner and the things that help you to focus and achieve your goals. With this understanding in mind, it is worth reflecting on ways that you can change your space or routine to support your learning. This can be anything from moving your laptop to be with your keys so you do not forget to take it with you, to changing the layout of your study so you are less distracted. Think deeply about the barriers to your learning and try to employ practical ways to solve some of the issues that you are facing.

It can be helpful to think about time management as energy management. The beauty of energy management is its focus on aligning tasks with your natural energy fluctuations. This is why it is so important to know yourself as a learner and work within the confines of your energy rhythms. Knowing how much energy a task will take is also beneficial, as it can help you make decisions concerning how your time is spent before and after its completion. Rather than simply scheduling tasks, focus on optimising your energy levels by incorporating breaks, conserving energy when necessary while prioritising nutrition, movement, and rest.

Once you have started to address some of your focus, energy management, and learning barriers, you can move on to using specific time management tools. Perhaps the most successful time management tool is called the Pomodoro technique. This technique seems to work especially well for students with focus issues such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). The Pomodoro technique was developed by Francesco Cirillo who was trying to combat his own procrastination while studying. He named the technique after his Pomodoro (the Italian word for tomato) shaped timer that he used to time himself.

To use this method, choose a task to be completed, then set a timer for 25 minutes. This 25-minute block of time is called a “Pomodoro”. While the timer is running, focus only on the task at hand and remove all potential distractions. When the timer rings, have a five-minute break. It is important to get up from your desk during this break time. Perhaps do some stretches or go for a short walk. You then complete the cycle (25 minutes of focus followed by a five-minute break) two to four more times. After this, you take a longer break of 15 to 30 minutes.

Importantly, you need to avoid all distractions during the Pomodoro’s. Do not check your phone, email, social media, or the time during a Pomodoro. If you are interrupted, let the person know that you are in the middle of something and that you will talk to them when the Pomodoro is complete.

When first completing a Pomodoro you might find it difficult to stick to the 25 minutes; feel free to make any adjustments you need. A 15-minute Pomodoro might be more achievable at first. There are several Pomodoro apps or websites that allow you to adjust the time of your Pomodoro’s and breaks.

The beauty of the Pomodoro technique is its short time frame. Instead of being overwhelmed by a longer task, committing to 25 minutes of focused study at a time can feel more achievable. Many students developing their skills in time management find this quite appealing. Additionally, the Pomodoro technique can help you to organise how long something might take you to complete. Writing an essay might take you 15 Pomodoro’s for instance. Scheduling those Pomodoro’s throughout the week might stop you feeling overwhelmed.

The Pomodoro technique touches on an important aspect of time management, and that is dedicated time to a task. There is no need to have every hour of every day planned out as this ignores your motivation levels and could put your mental health in jeopardy. But planning to spend concentrated time on tasks while removing distractions and giving yourself the best chance to focus is a skill worth developing.

After some time, you can adjust the length of your study to suit your own personal needs and challenges. Here are some other time management tools that you might find useful:

Eat that frog

Eat that frog is the idea that you choose the most pressing or challenging task first. Completing the most difficult task first is said to have the most positive impact on your progress. Some students also have a ‘difficult hour’, where they choose one hour a week to complete the difficult tasks that were left incomplete.

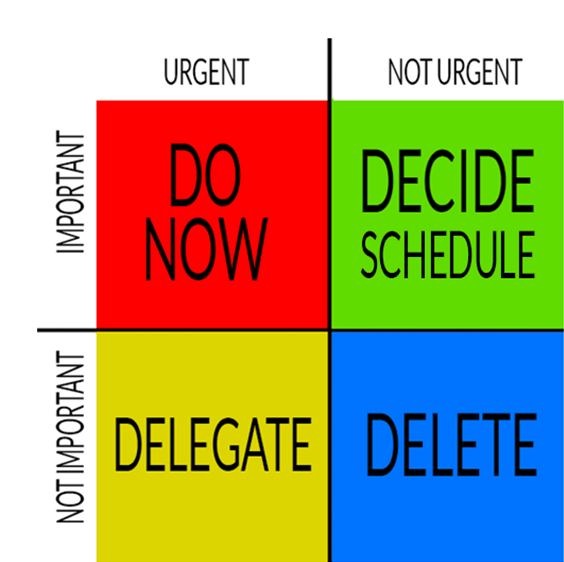

Eisenhower Matrix

This tool is great for prioritising your tasks. There are 4 quadrants, Urgent and Important; Important, Not Urgent; Urgent, Not Important and; Not Urgent, Not Important. Where the task lands helps you to choose what to do. Anything Urgent and Important should be done right away, while Important, Not Urgent tasks should be scheduled. Urgent, Not Important tasks are usually delegated to someone else (probably more important when you start working) and anything that is Not Urgent, Not Important would simply be deleted. The aim would be to avoid elements falling into the Urgent and Important category, as it can become quite stressful and is difficult to maintain long term. The colourful box below is a good guide to this tool.

Pickle jar theory

The pickle jar theory is another prioritising tool that helps you to sort tasks into three categories: important, less important, and trivial. The important tasks in this metaphor are like big pickles being put into a jar. The less important tasks are smaller pickles that fall to fill the spaces between the big pickles. Trivial tasks are like water or sand, and they fill the crevasses between the pickles. Taking the metaphor further, if we are to fill the pickle jar with sand (or the less important tasks), there will be no room for any pickles (important or less important tasks). Giving your tasks one of these three labels should help you to decide how much time should be spent on them.

Task Batching Technique

The Task Batching Technique involves grouping similar tasks together and completing them over a dedicated block of time. The idea behind this technique is to reduce cognitive load by only doing one type of task at a time. Despite popular opinion, multitasking, especially with technology, can be detrimental to our learning (Carrier et al., 2015). For example, instead of checking your emails several times a day for instance, you could have a dedicated time to check them once each day.

You can see by these techniques that time management is more about refining your priorities than what you do with your time. Some of these aspects might speak to you, and others might not, so it is advisable that you experiment as you try to master your time management skills.

4.5 Key strategies from this chapter

- Develop a reader voice: Engage in an internal dialogue when you read by asking questions, making connections, and reflecting on what you do not understand.

- Know why you are reading: Have a clear purpose or question in mind before you start reading to help maintain focus.

- Ask questions: Pose questions before and during your reading to deepen your engagement and guide your learning.

- Use reading strategies: Strategies such as previewing, skimming, scanning, and detailed reading can help you better navigate your readings.

- Developing a reading habit: Read daily to build a consistent reading habit, rewarding yourself to reinforce the practice.

- Change the way you take notes: Using the Cornell Note-taking method as a starting point, devise your own note taking system that is meaningful to you.

- Use the Pomodoro technique: Break study time into 25-minute focused intervals, followed by a 5-minute break, to improve focus and reduce procrastination.

- Explore other productive strategies: “Eat that frog”, the Eisenhower matrix, pickle jar theory, and task batching techniques are all strong strategies to prioritise and focus on your tasks.

4.6 Chapter summary

In this chapter, we have:

- focussed on reading, note-taking, and time management as crucial skills for higher education success.

- discussed reading techniques that improve overall reading strategy.

- examined the structure and anatomy of a journal article to aid in effective academic reading.

- introduced how the Cornell note-taking method could be approached creatively to make notes more meaningful and fit for purpose.

- reviewed a series of time management strategies to assist with using time more effectively.

4.7 Reflection questions

- How do your current reading habits align with the strategies discussed in this chapter? Which strategies might you incorporate to improve your reading resilience?

- Reflect on your note-taking techniques. How might the Cornell method enhance the quality of your notes?

- Which time management strategy resonates most with your personal study routine? How can you implement it to improve your academic productivity?

- Consider the barriers you face in your academic studies. How might adjusting your study environment or routine help you overcome these challenges?

- How do you manage your academic tasks in relation to other responsibilities, such as work or family? What strategies from this chapter could help you better align your priorities?

References

Bargmann, C., & Kauffeld, S. (2023). The interplay of time management and academic self-efficacy and their influence on pre-service teachers’ commitment in the first year in higher education. Higher Education, 86(6), 1507-1525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00983-w

Carrier, L. M., Rosen, L. D., Cheever, N. A., & Lim, A. F. (2015). Causes, effects, and practicalities of everyday multitasking. Developmental Review, 35, 64-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2014.12.005

Douglas, K., Barnett, T., Poletti, A., Seaboyer, J., & Kennedy, R. (2016). Building reading resilience: Re-thinking reading for the literary studies classroom. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(2), 254-266. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1087475

MacCann, C., Fogarty, G. J., & Roberts, R. D. (2012). Strategies for success in education: Time management is more important for part-time than full-time community college students. Learning and Individual Differences, 22(5), 618-623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2011.09.015

Nieuwoudt, J. E., & Pedler, M. L. (2023). Student retention in higher education: Why students choose to remain at university. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 25(2), 326-349. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025120985228

Pauk, W., & Owens, R. J. Q. (2010). How to study in college (10th ed.). Wadsworth.

I would love to hear your thoughts on this chapter, share your feedback.