Chapter 14: Nursing

James Bonnamy; Katrina Récoché; Steve Wise; and Gabrielle Brand

Uncertainty in Nursing

Nurses are the cornerstone of healthcare systems globally, making up the world’s largest health professions workforce through their diverse roles, ranging from delivering acute care in hospitals to preventive care in the community (World Health Organization, 2024). Nursing, as a profession, is rapidly evolving as governments recognise that investing in nurses is good value for money, driving improved health outcomes, global health security, and inclusive economic growth (World Health Organization, 2024). Nurses need to be prepared to respond to emerging global health issues and clinical uncertainty inherent in dynamic and ever-changing healthcare systems.

Nurses are practising in increasingly complex systems, making frequent decisions and clinical judgements, often without all relevant information. For example, a person who seeks care after being diagnosed with cancer should receive care from a multidisciplinary team (Borras et al., 2014), but referrals may take time to be actioned, and in the meantime, nurses need to plan and provide care without the multidisciplinary team’s input. In doing so, nurses are challenged by clinical uncertainty that is pervasive across settings and specialities (Ilgen et al., 2021). The natural variation that occurs in clinical practice and the subsequent inconsistencies in patient outcomes contribute to uncertainty, as do the multiple ways of knowing and solving clinical problems (e.g., personal knowledge versus prior professional experiences) (Cranley et al., 2009).

Nurses work in multidisciplinary teams, providing and receiving information for clinical decision-making. They must critique the information they receive and determine how it influences their own clinical decisions, which can stimulate uncertainty during decision-making (McCaughan, 2002). The decisions that nurses make are frequently scrutinised by other clinicians and administrators, and when care falls short of expected standards, regardless of the (often) systemic reasons, nurses’ shoulder much of the responsibility (Hughes, 2008). Some doctors are not open to nurses who seek clarification about a particular medical request, and they can become frustrated if the nurse is unable to provide the necessary information when required (LeTourneau, 2004). Gender may also contribute to uncertainty; though there are many nurses who are men, the large majority of nurses are still women, and most doctors are still men, which may draw upon the historical oppression of women in jobs, wealth, and power in society (LeTourneau, 2004). Interdisciplinary tensions also exist between doctors and nurses due to nurses increased scope of practice and role autonomy (Weiland et al., 2010), when traditionally they received ‘orders’ from doctors as subservient clinicians (Samuriwo et al., 2020).

There are many examples of career uncertainty when student nurses transition to independent clinical practice. After graduating, nurses face uncertainty in where they will undertake their supported graduate year. Graduates are matched with healthcare services which then allocate their graduates to various specialities. Some graduates may have little or no experience in their allocated speciality, meaning they face unfamiliar diseases, treatments, and experiences. Newly graduated nurses lack the tacit knowledge gained through experience and can struggle with bridging the theory and practice gap, especially when trying to comprehend rationales for care decisions made by their senior colleagues who do so seemingly without effort (Ingvarsson et al., 2019).

Uncertainty similar to that recognised in doctors is experienced by senior nurses with advanced practice roles (e.g., clinical nurse consultants, nurse practitioners, and advanced practice nurses) that involve making medical diagnoses, ordering and interpreting investigations, and making autonomous decisions (e.g., admitting or discharging patients from hospital) (Thompson & Yang, 2009). For example, new nurse practitioners face uncertainty when deploying their knowledge and skills to recognise obvious or subtle patient cues when making diagnoses or determining treatments (Barnes et al., 2004). Nurse practitioners also experience uncertainty when attempting to integrate their expanded scope of practice into their existing professional nursing identities, as well as when responding to mixed reactions from other healthcare professionals about nurses’ scope of practice and their roles in healthcare (Weiland et al., 2010).

All nurses, regardless of their career stage, face uncertainty in clinical practice. Uncertainty can be stimulated by gaps in evidence and the unpredictability that arises when caring for patients (e.g., probability, ambiguity, and complexity) (Hillen et al., 2017). Graduate nurses are expected to seek out evidence and provide evidence-based care, but evidence is not always available or is contradictory (ambiguity). For example, debate continues over whether urinary catheter maintenance solutions, used to unblock a urinary catheter, are effective or safe, leaving nurses with uncertainty about the best approach for blocked urinary catheters (i.e., using a catheter maintenance solution or replacing the urinary catheter) (Shepherd et al., 2017). Patient responses to treatment are also uncertain; for example, chemotherapy does not offer a cure for everyone diagnosed with cancer, and this uncertainty is difficult for nurses to communicate to patients who commence chemotherapy with a curative intent (probability) (Mansoori et al., 2017).

Nurses face uncertainty relating to their healthcare workplace structure, culture, and expectations. International mobility among nurses is increasing, meaning many will practise in unfamiliar environments within various healthcare hierarchies and structures. For example, in some parts of the world (e.g., Victoria in Australia, California in the United States), there are mandated nurse-to-patient ratios, stipulating the number of nurses (and midwives) required for each shift based on the number of patients on the ward or unit (Coffman et al., 2002; Safe Patient Care Act, 2015). There is also great variation in roles and titles for nurses; for example, the senior nurse responsible for hospital operations after hours and on weekends is known by up to 18 different titles in the United States (Weaver et al., 2018). There is also variation in the culture of nursing practice; some nurses, for instance, are permitted to prepare and administer injectable medications alone, whereas others must perform double-checking of the same drugs. There is even uncertainty over whether single- or double-checking of medications reduces the risk of errors (Koyama et al., 2020).

Finally, expectations and perceptions of nurses around the world vary too, with organisational, economic, sociological, demographic, and planetary health changes transpiring in global healthcare systems (Holst, 2020). Furthermore, nurses experience unpredictable community responses to their efforts, illustrated by the violence directed at nurses by anti-vaccination extremists during the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines (Zhang et al., 2023). Nurses who are men also face uncertainty over patient attitudes, with some patients holding negative views about and even refusing care from male nurses (Adeyemi-Adelanwa et al., 2016). Other forms of discrimination, such as racism, are also exhibited towards nurses by patients and colleagues (Jefferies et al., 2022).

Priorities to Prepare Learners for Uncertainty in Nursing

The presence of uncertainty in everyday nursing practice, and the discomfort it brings, risks care being reduced to tick-box episodes based on checklists (Lazarus, 2023). Most nurses can be ‘quite obsessed’ with checklists, because they help them feel in control, counterbalancing the unpredictability of a person’s health and response to care (Lazarus, 2023, p. 65). To not only cope but to thrive in increasingly complex and uncertain healthcare environments, nurses must be able to identify sources of uncertainty. Additionally, they must develop strategies to recognise and manage emotional responses to uncertainty, enabling decision-making to progress patient care in spite of uncertainty. Without this capacity to identify and manage uncertainty, nurses are more likely to suffer burnout, and when this occurs, their behaviour and actions (or omissions) negatively affect patient care (Di Trani et al., 2021). Burnout is extremely common among nurses, with rates increasing enormously since the COVID-19 pandemic, due to exhaustion from irregular working hours, frequent overtime, the risk of contracting COVID-19 at work, and subsequent concerns about infecting close family members (Ge et al., 2023). A systematic review and meta-analysis by Galanis et al. (2021) found that the overall prevalence of emotional exhaustion among nurses was 34.1 per cent, including elements of depersonalisation (12.6%) and lack of personal accomplishment (15.2%).

Nurses with lower uncertainty tolerance may waste time, healthcare resources, and cognitive reserves trying to minimise uncertainties and unknowns (Strout et al., 2018). They may also avoid making decisions (delaying patient care), feel vulnerable (impacting on interprofessional relationships), or act without thinking (causing patient harm) to avoid discomfort stimulated by uncertainty. Despite previous thinking that uncertainty tolerance is an unchanging personality trait, there is evidence that demonstrates health professions education can either hinder or foster uncertainty tolerance in learners (Stephens et al., 2021). Therefore, nurses need preparatory education to stimulate uncertainty tolerance and learn to embrace uncertainty, and this should be prioritised during their undergraduate education. The following activity demonstrates how uncertainty tolerance can be cultivated in undergraduate nursing students.

Fostering Uncertainty Tolerance in Nursing Learners

Assessment is considered a motivator for learning (Fischer et al., 2024). Embedding sources of uncertainty within nursing learners’ assessments may aid with illustrating the importance of uncertainty in healthcare and help to foster uncertainty tolerance. The exemplar activity described below is a summative assessment (which contributes to the learner’s final unit mark) that involves a reciprocal exchange of ideas between a novice learner and an expert. It demonstrates assessment for and assessment of learning. Unique to this approach is the bidirectional feedback process, in which the learner submits their assessment, receives feedback from an expert, and is then given an opportunity to critique and integrate that feedback, learning from the expert’s intellectual candour through the sharing of professional decision-making (Bearman & Molloy, 2017). The learners benefit from participating in an authentic assessment which mimics the actualities and complexities of planning care in clinical practice, including varying professional opinions, lack of clear evidence-based recommendations, and time constraints (Ajjawi et al., 2024).

Exemplar Activity: Integrating Science and Practice

Activity Origin

This case was developed and implemented in the School of Nursing and Midwifery at Monash University, Melbourne.

Sources of Uncertainty

This Integrating Science and Practice (iSAP) summative assessment case provides learners with examples of uncertainties faced by nurses who care for those diagnosed with cancer. Cancer is the second leading cause of death worldwide, with the global cancer burden expected to reach 28.4 million cases in 2040, a 47 per cent rise from 2020 (Sung et al., 2021). Due to advances in diagnosis and treatment, cancer survivorship has increased, with global numbers projected to grow to 26 million by 2040 (American Cancer Society, 2022). For many people, cancer is now a chronic disease, hallmarked by a lack of evidence of disease in the presence of ongoing complications caused by the cancer or its treatments (Pizzoli et al., 2019). Uncertainty is a core aspect of all cancer patients’ experiences, with the course of the neoplasm and treatment effectiveness both unpredictable and inconsistent among those diagnosed with the disease.

Uncertainty may present at any point in the patient’s experience with cancer, beginning with diagnosis (e.g., shock of diagnosis, extent of the spread), initiation of new treatments (e.g., anticipated side effects), and transitions of care (e.g., from curative to palliative care). Up to 30–50 per cent of cancer survivors face significant psychological distress due to the uncertainty of survivorship (Rodriguez-Gonzalez et al., 2022). The uncertainty occurs due to unfamiliar symptoms, healthcare environments, and treatments, and to expectations being inconsistent with experiences (Zhang, 2017). Support to manage uncertainty is often not delivered, which can cause sleep disturbances, depression, anxiety, and reduced quality of life for those diagnosed with cancer (Guan, Santacroce, et al., 2020). Common sources of uncertainty for cancer survivors are the follow-up scans, blood tests, and appointments; the agony caused by these is so common that it has been given a name, scanxiety (Lazarus, 2023). In addition, each physical symptom experienced during survivorship can be misinterpreted as cancer recurrence instead of something more likely.

The uncertainty of a cancer diagnosis can also extend to families of patients living with cancer. Some studies have shown that patients’ partners can experience higher levels of uncertainty than the patients themselves (Guan, Guo, et al., 2020). Worsening feelings of uncertainty in families often occurs with the progression of cancer in patients. For example, uncertainty about the outcomes of childhood cancers (e.g., relapse and recurrence) increases parental distress and dysfunctional behaviours (Vander Haegen & Etienne, 2018). Education for nurses about uncertainty tolerance is important, because the identification of uncertainty intolerance and its associated outcomes in cancer patients’ families are essential for implementation of strategies that support both the family and the patient (Vander Haegen & Etienne, 2018). For example, it has been demonstrated that parental uncertainty influences the level of uncertainty experienced by chronically ill children and children receiving treatment (Page et al., 2012). It is critical for nurses to help families to perform their familial roles and responsibilities in new and unfamiliar circumstances in order to deal with the challenges that arise following a life-threatening diagnosis (Lewandowska, 2021).

Despite being called upon to help patients and their families navigate the uncertainty associated with a cancer diagnosis, nurses themselves experience uncertainty in caring for patients and their families. Changing cancer demographics (e.g., young-onset colorectal cancer), novel treatment options (e.g., immunotherapy), and variable survival rates are sources of uncertainty for nurses caring for those diagnosed with cancer. In addition, individual patient responses to a cancer diagnosis are widely variable; for most, a cancer diagnosis is unexpected and incongruent with their previously held healthy identity (Kirby et al., 2020). A cancer diagnosis is experienced in diverse ways and is shaped by many factors which have important implications for clinical care. Consequently, nurses must be able to recognise and respond to uncertainty experienced by patients, families, and within themselves to ensure optimal care delivery.

Facilitator Guide

This activity is an oncology summative assessment task that purposefully stimulates uncertainty in learners to help prepare them for the unpredictable aspects of caring for someone following a cancer diagnosis. The activity uses an iSAP educational approach, which fuses theory with complex clinical practice situations, engaging experts to enhance learning and translate theory to practice, bridging the theory–practice gap by contextualising learning (Williams et al., 2017). An iSAP case comprises five elements:

- Case scenario

- Professional issues

- Clinical action plan

- Expert or practitioner response

- Comparative report or reflective analysis.

The aim of the activity is for learners to recognise the nurse’s role in providing high-quality, person-centred, holistic care to people living with cancer and those who care for them and to acknowledge the uncertainties that follow a cancer diagnosis. Engagement with the activity will give learners the opportunity to do the following:

- discuss and critically reflect on key principles, philosophies, and approaches that underpin the care of patients requiring oncology care

- critically examine the role of nursing within the multidisciplinary team

- critique the effectiveness of pharmacological and evidence-based complementary therapy options for pain management in cancer care

- describe common side effects experienced by patients receiving chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and adjuvant therapies.

The activity was designed for a core nursing unit which focuses on the management of pain, oncology, and palliative and end-of-life care in the second year of a three-year bachelor degree. It is built in the Moodle learning management system using the eBook function and includes an interactive HTML5 Package plug-in to improve learner engagement. The content could be integrated into any learning management system along with the plug-in activities, which are cross-platform compatible.

The assessment was implemented after learners had attended two to three clinical placements (moderator: subject proficiency). Not all learners would have cared for someone newly diagnosed with cancer; however, most would have cared for someone with a history of cancer, and with cancer being increasingly recognised as a chronic disease, the uncertainty that follows the initial diagnosis may continue for many years (Pituskin, 2022) (moderator: scaffolding uncertainty).

The author of the case scenario wrote from the lived-experience perspective of someone newly diagnosed with cancer, and the text was produced shortly after the author had finished primary cancer treatment. The accompanying documentation included their own pathology and radiology reports, as well as pictures of their recovery. Developing the activity in partnership with a young-onset colorectal cancer survivor ensured an authentic richness to the case scenario and gave learners access to the emotions that a cancer diagnosis prompts, which could not be imagined by an educator who lacked such lived experience.

To successfully facilitate this activity, the educator must have clinical oncology experience and be familiar with the uncertainties that are omnipresent for a person following a cancer diagnosis. It is beneficial for the educator to have considered these uncertainties so they can demonstrate their metacognition about the case scenario and its uncertainties when responding to learners’ clinical action plans and comparative reports.

Activity

Case Scenario

The scenario features Matthew, a young man who visits his general practitioner with painless rectal bleeding occurring intermittently for the past six months. Following a gastroscopy and colonoscopy, Matthew is advised that a large, nearly circumferential mass has been found in his distal colon/proximal rectum, with a likely diagnosis of colorectal cancer. This is a very unexpected diagnosis for Matthew, his family, and his healthcare team, who had all anticipated a less sinister cause of his rectal bleeding.

This technically based scenario is enriched with psychosocial issues to mirror the messy, complex reality of clinical practice (e.g., unexpected diagnoses, gender biases, interdisciplinary care). Matthew is only 30 years old at the time of his cancer diagnosis, challenging traditional knowledge that colorectal cancer is a disease of older age, despite the incidence in those under 50 years of age steadily increasing (Sifaki-Pistolla et al., 2022). Matthew does not have any children, so there are complexities around fertility preservation prior to commencing chemotherapy, especially when considering gender biases and norms for a young gay man.

Matthew works as a registered nurse and has provided care to people living with and dying from cancer, adding an extra layer of psychosocial complexity, as he integrates his previous clinical experiences with his own lived experience following his cancer diagnosis. Healthcare professionals who become patients can experience additional uncertainty (Bonnamy, 2020) if members of their care team take different approaches to their care once they discover their dual Identity as patient and clinician (Svantesson et al., 2016).

The case is delivered through a branching scenario in an HTML5 Package plug-in and then embedded into the iSAP (moderator: uncertainty dress rehearsal). It is infused with actual medical documentation (used with permission), including reports on radiology and pathology (moderator: scaffolding uncertainty). It also includes pictures of a painful skin reaction Matthew experiences on his hands and feet from treatment with capecitabine (chemotherapy). These documents provide context for the learners, encourage reflection (‘What if that was me?’), and stimulate further learning (moderator: reflective learning).

Clinical Action Plan

After familiarising themselves with the scenario, learners are directed to apply critical thinking to plan Matthew’s care within the scope of practice of a registered nurse (moderator: setting clear roles). Using their scientific knowledge, clinical experience, and relevant literature, they generate a clinical action plan that meets Matthew’s care needs and addresses the assessment’s learning outcomes (moderator: career value). They submit the completed clinical action plan for assessment (moderator: flexible assessments).

The clinical action plan needs to have two parts. The first relates to discharge planning considerations for Matthew and his family following his cancer diagnosis. The second involves recognising and responding to acute deterioration when Matthew is readmitted to the oncology ward after developing a fever and cough.

The question prompts for the clinical action plan are designed to reinforce concepts already taught, particularly regarding how the psychological response to a cancer diagnosis is unique and unpredictable for each individual and how this extends to their family, friends, and healthcare professionals (moderator: subject proficiency). Learners’ clinical and theoretical experience has largely had an acute inpatient care focus up to this point in their degree. Discharge planning for Matthew challenges learners to plan care to be delivered by primary and community care providers. In acute hospitals, access to a broad range of multidisciplinary professionals is common, but in the community setting, there are often long waiting lists, especially for some professional groups, and limitations on other resources and consumables. Careful planning and referrals are therefore necessary to facilitate high-quality patient- and family-centred care for Matthew. This learning is based in the real world, as the learners must grapple with the realities that patients and their families face in trying to access sometimes scarce resources after discharge from hospital.

Expert Response

An expert who is familiar with the case scenario responds to learners’ clinical action plans following their submission (moderator: expert guidance). The expert takes each learner through their approach to the scenario, including how they would identify, respond to, and escalate acute deterioration, as well as how they would thoughtfully recognise the impact a cancer diagnosis may have had on Matthew and his family when identifying relevant supports for discharge with rationales. The expert provides a holistic response: shifting the focus from acute inpatient care to primary and community care for the sustainable management of Matthew’s health and wellbeing.

Comparative Report

In this stage, learners are required to produce a comparative report or reflective analysis for assessment (moderator: reflective learning). The report or analysis must include the following elements:

Comparison between learner and expert approaches This identifies the similarities and differences between the learner’s clinical action plan and that of the expert. Dot points or a table can be used (moderator: capacity for reflection).

Reflection on learning Learners describe how the expert’s response consolidated and/or challenged their previous knowledge and understanding of the aspects of care they investigated (moderator: cognitive flexibility).

Impact on practice Learners suggest how the knowledge gained about caring for a patient with oncology needs will affect or enhance their future practice (moderator: sense of purpose). They must include at least two specific strategies that will be embedded in their practice as a result.

The purpose of this stage is to deepen learners’ understanding of complex clinical situations, to alert them to the risks of a poorly constructed or informed knowledge base to holistic care, and to identify their personal knowledge and learning gaps.

Impact

This activity was formally assessed, with anonymous feedback provided by learners through end-of-semester teaching and learning evaluations. The quotations in parentheses below are drawn from this feedback. Learners demonstrated an appreciation of the challenges people face following a cancer diagnosis. (‘This assignment has really solidified for me how time critical oncology emergencies are, both for the patient to present themselves for medical treatment, and for practitioners to respond in the clinical setting). Many students were able to recognise that an acute-care lens would be inadequate to guide holistic care for Matthew and his family following discharge into the community, which is where most people living with cancer receive their treatment. (‘Whilst I believe I did research and provide holistic community resources for Matthew, the expert referred to some areas of support I had not considered. For example, fertility support and additional allied health services.’) Students also acknowledged that a methodical approach to assessment and care may not always apply in areas of uncertainty. (‘Before viewing the expert response, I planned care components as segments. The mention of multitasking NS [neutropenic sepsis] management has challenged my isolated, black-and-white and checklist approach to nursing care.’)

As described above, the students were challenged to extend their learning and uncertainty tolerance by considering how they might apply the learning from the activity to their future practice. Students recognised the power of reflection in practice. (‘I believe reflective practices to be of benefit to my current practice and beyond … Taking the time to consider what went well, what could have been improved or perhaps areas that were missed can only improve my skills and preparation for future events that I may be a part of.’)

Adaptations and Summary

This activity was adapted following its initial implementation to further enhance learner uncertainty tolerance, with the facilitator explicitly identifying where uncertainty may appear in oncology practice as part of their expert response to learners’ critical action plans. Through sharing their metacognition and their own uncertainties about caring for someone following a cancer diagnosis and about the actions required to address the needs of patients, the facilitator made clear that uncertainty exists and that it should not provoke inaction or rushed decision-making to avoid the discomfort that comes with low uncertainty tolerance (moderator: intellectual candour).

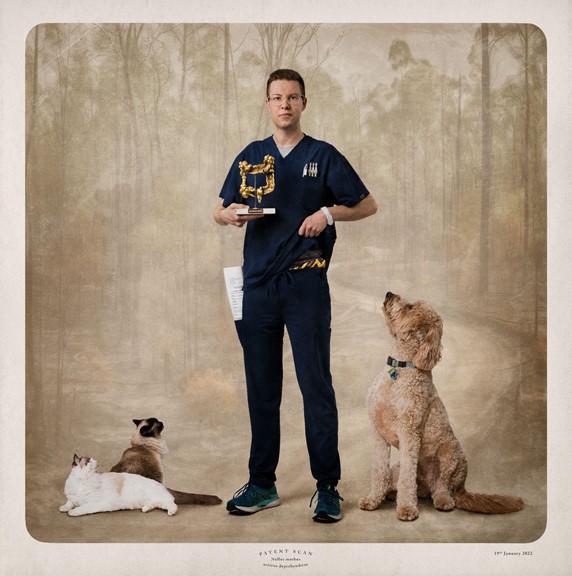

To add further layers of uncertainty and to acknowledge the voice of the person with lived experience of cancer, the scenario was adapted to include a portrait of Matthew which was available to students after they submitted their critical action plan (Figure 14.1). The portrait contains narrative artefacts important to Matthew during his experience with cancer (Bonnamy, 2020). The portrait was developed by James Bonnamy, the lead author of this chapter, whose own experience of living with cancer is shared in the scenario, and Steve Wise, a medical and portrait photographer and a co-author of this chapter, who is accomplished at listening to stories and turning them into portraits of strength. The portrait is untitled, and there is no accompanying written narrative. Learners are left to consider in their own time the narrative artefacts and meanings in the portrait and what these might mean to Matthew in the case scenario.

The background image is taken from the Australian bush, with gum trees standing tall and defiant, having survived a torrid bushfire season. Their new growth is representative of James’ personal and professional growth after his cancer diagnosis. At an undetermined point in the uncertain and winding track stands James, looking ahead. In the pocket of his scrub pants are the results of his last scan, indicating no evidence of disease – the words every cancer survivor nervously hopes to hear and which are printed in Latin at the bottom of the portrait: ‘Patent scan. Nullus morbus activus deprehenditur’ (Clear scan. No evidence of active disease). At his feet (from left to right) are Lucy, Grace, and Charlie, his beloved pets, keeping a watchful eye on him, surrounding him, and protecting him from what may arise as he continues to walk along the winding track of survivorship.

Peeking out from under his scrubs are the pyjamas he wore in hospital after his surgery; he refused to wear a gown or to acquiesce to the classic role of the ‘sick’. His hospital wristband is a shackle he wears each year, tying him to the scanxiety he experiences when he returns for follow-up procedures, a reminder of the fragility and uncertainty of cancer survivorship and recovery. In his scrub top pocket is a four-pen and three intravenous cannulas, representative of the duality of his role as a researcher-writer and registered nurse. Finally, there is a golden model bowel covered in diamantes and featuring an engraving that reads, ‘In memoriam’ – a gift from academic bioscience colleagues who knew exactly what would bring a smile to a face weary from the burden of a cancer diagnosis.

Conclusion

Nurses face uncertainty in their everyday practice. Nurses with low uncertainty tolerance are likely to experience difficulty making decisions and higher levels of burnout. Teaching undergraduate nurses uncertainty tolerance is critical, so that when they graduate, they can use reasoning and judgement to make safe decisions, even when uncertainty exists because of their environment, workplace culture, or individual patient characteristics. Significant uncertainty exists for patients and nurses following a cancer diagnosis, and patients will turn to nurses for guidance to navigate this uncertainty and to try to avoid its many negative psychological impacts. It is therefore important that nurse educators find creative ways to help nurse learners feel safe when developing strategies to tolerate uncertainty.

References

Adeyemi-Adelanwa, O., Barton-Gooden, A., Dawkins, P., & Lindo, J. L. (2016). Attitudes of patients towards being cared for by male nurses in a Jamaican hospital. Applied Nursing Research, 29, 140–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2015.06.015

Ajjawi, R., Tai, J., Dollinger, M., Dawson, P., Boud, D., & Bearman, M. (2024). From authentic assessment to authenticity in assessment: Broadening perspectives. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 49(4), 499-510. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2023.2271193

American Cancer Society. (2022). Cancer treatment & survivorship facts & figures. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/survivor-facts-figures.html

Barnes, H., Crumbie, A., Carlisle, C., & Pilling, D. (2004). Patients’ perceptions of ‘uncertainty’ in nurse practitioner consultations. British Journal of Nursing, 13(22), 1350–1354. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2004.13.22.17275

Bearman, M., & Molloy, E. (2017). Intellectual streaking: The value of teachers exposing minds (and hearts). Medical Teacher, 39(12), 1284–1285. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1308475

Bonnamy, J. (2020). Holding multiple identities: A personal narrative of young onset colorectal cancer. Journal of Cancer Education, 35, 1261–1266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01740-2

Borras, J. M., Albreht, T., Audisio, R., Briers, E., Casali, P., Esperou, H., Grube, B., Hamoir, M., Henning, G., Kelly, J., Knox, S., Nabal, M., Pierotti, M., Lombardo, C., van Harten, W., Poston, G., Prades, J., Sant, M., Travado, L., . . . Wilson, R. (2014). Policy statement on multidisciplinary cancer care. European Journal of Cancer, 50(3), 475–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2013.11.012

Coffman, J. M., Seago, J. A., & Spetz, J. (2002). Minimum nurse-to-patient ratios in acute care hospitals in California. Health Affairs, 21(5), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.53

Cranley, L., Doran, D. M., Tourangeau, A. E., Kushniruk, A., & Nagle, L. (2009). Nurses’ uncertainty in decision-making: A literature review. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 6(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6787.2008.00138.x

Di Trani, M., Mariani, R., Ferri, R., De Berardinis, D., & Frigo, M. G. (2021). From resilience to burnout in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 emergency: The role of the ability to tolerate uncertainty. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646435

Fischer, J., Bearman, M., Boud, D., & Tai, J. (2024). How does assessment drive learning? A focus on students’ development of evaluative judgement. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 49(2), 233–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2023.2206986

Galanis, P., Vraka, I., Fragkou, D., Bilali, A., & Kaitelidou, D. (2021). Nurses’ burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(8), 3286–3302. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14839

Ge, M. W., Hu, F. H., Jia, Y. J., Tang, W., Zhang, W. Q., Zhao, D. Y., Shen, W. Q., & Chen, H. L. (2023). COVID-19 pandemic increases the occurrence of nursing burnout syndrome: An interrupted time-series analysis of preliminary data from 38 countries. Nurse Education in Practice, 69, Article 103643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2023.103643

Guan, T., Guo, P., Santacroce, S. J., Chen, D. G., & Song, L. (2020). Illness uncertainty and its antecedents for patients with prostate cancer and their partners. Oncology Nursing Forum, 47(6), 721–731. https://doi.org/10.1188/20.ONF.721-731

Guan, T., Santacroce, S. J., Chen, D. G., & Song, L. (2020). Illness uncertainty, coping, and quality of life among patients with prostate cancer. Psychooncology, 29(6), 1019–1025. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5372

Hillen, M. A., Gutheil, C. M., Strout, T. D., Smets, E. M., & Han, P. K. (2017). Tolerance of uncertainty: Conceptual analysis, integrative model, and implications for healthcare. Social Science & Medicine, 180, 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.024

Holst, J. (2020). Global health: Emergence, hegemonic trends and biomedical reductionism. Globalization and Health, 16(1), Article 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00573-4

Hughes, R. G. (2008). Nurses at the ‘sharp end’ of patient care. In R. G. Hughes (Ed.), Patient safety and quality: An evidence-based handbook for nurses. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2672/

Ilgen, J. S., Teunissen, P. W., de Bruin, A. B., Bowen, J. L., & Regehr, G. (2021). Warning bells: How clinicians leverage their discomfort to manage moments of uncertainty. Medical Education, 55(2), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14304

Ingvarsson, E., Verho, J., & Rosengren, K. (2019). Managing uncertainty in nursing: Newly graduated nurses’ experiences of introduction to the nursing profession. International Archives of Nursing and Health Care, 5(1), Article 119. https://doi.org/10.23937/2469-5823/1510119

Jefferies, K., States, C., MacLennan, V., Helwig, M., Gahagan, J., Bernard, W. T., Macdonald, M., Murphy, G. T., & Martin-Misener, R. (2022). Black nurses in the nursing profession in Canada: A scoping review. International Journal for Equity in Health, 21, Article 102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-022-01673-w

Kirby, E. R., Kenny, K. E., Broom, A. F., Oliffe, J. L., Lewis, S., Wyld, D. K., Yates, P. M., Parker, R. B., & Lwin, Z. (2020). Responses to a cancer diagnosis: A qualitative patient-centred interview study. Supportive Care in Cancer, 28, 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04796-z

Koyama, A. K., Sheridan Maddox, C. -S., Li, L., Bucknall, T., & Westbrook, J. I. (2020). Effectiveness of double checking to reduce medication administration errors: A systematic review. BMJ Quality & Safety, 29(7), 595–603. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009552

Lazarus, M. D. (2023). The uncertainty effect: How to survive and thrive through the unexpected. Monash University Publishing.

LeTourneau, B. (2004). Physicians and nurses: Friends or foes? Journal of Healthcare Management, 49(1), 12–15.

Lewandowska, A. (2021). Influence of a child’s cancer on the functioning of their family. Children, 8(7), Article 592. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8070592

Mansoori, B., Mohammadi, A., Davudian, S., Shirjang, S., & Baradaran, B. (2017). The different mechanisms of cancer drug resistance: A brief review. Advanced Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 7(3), 339–348. https://doi.org/10.15171/apb.2017.041

McCaughan, D. (2002). What decisions do nurses make? In C. Thompson & D. Dowding (Eds.), Clinical decision-making and judgement in nursing (pp. 95–108). Churchill Livingstone.

Page, M. C., Fedele, D. A., Pai, A. L., Anderson, J., Wolfe-Christensen, C., Ryan, J. L., & Mullins, L. L. (2012). The relationship of maternal and child illness uncertainty to child depressive symptomotology: A mediational model. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 37(1), 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsr055

Pituskin, E. (2022). Cancer as a new chronic disease: Oncology nursing in the 21st century. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal, 32(1), 87–92. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8849169/

Pizzoli, S. F., Renzi, C., Arnaboldi, P., Russell-Edu, W., & Pravettoni, G. (2019). From life-threatening to chronic disease: Is this the case of cancers? A systematic review. Cogent Psychology, 6(1), Article 1577593. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2019.1577593

Rodriguez-Gonzalez, A., Velasco-Durantez, V., Martin-Abreu, C., Cruz-Castellanos, P., Hernandez, R., Gil-Raga, M., Garcia-Torralba, E., Garcia-Garcia, T., Jimenez-Fonseca, P., & Calderon, C. (2022). Fatigue, emotional distress, and illness uncertainty in patients with metastatic cancer: Results from the prospective NEOETIC_SEOM study. Current Oncology, 29(12), 9722–9732. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29120763

Safe Patient Care (Nurse to Patient and Midwife to Patient Ratios) Act 2015 (Vic).

Samuriwo, R., Laws, E., Webb, K., & Bullock, A. (2020). ‘I didn’t realise they had such a key role.’ Impact of medical education curriculum change on medical student interactions with nurses: A qualitative exploratory study of student perceptions. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 25, 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-019-09906-4

Shepherd, A. J., Mackay, W. G., & Hagen, S. (2017). Washout policies in long-term indwelling urinary catheterisation in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004012.pub5

Sifaki-Pistolla, D., Poimenaki, V., Fotopoulou, I., Saloustros, E., Mavroudis, D., Vamvakas, L., & Lionis, C. (2022). Significant rise of colorectal cancer incidence in younger adults and strong determinants: 30 years longitudinal differences between under and over 50s. Cancers, 14(19), Article 4799. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14194799

Stephens, G. C., Rees, C. E., & Lazarus, M. D. (2021). Exploring the impact of education on preclinical medical students’ tolerance of uncertainty: A qualitative longitudinal study. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 26(1), 53–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-020-09971-0

Strout, T. D., Hillen, M., Gutheil, C., Anderson, E., Hutchinson, R., Ward, H., Kay, H., Mills, G. J., & Han, P. K. (2018). Tolerance of uncertainty: A systematic review of health and healthcare-related outcomes. Patient Education and Counseling, 101(9), 1518–1537. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.03.030

Sung, H., Ferlay, J., Siegel, R. L., Laversanne, M., Soerjomataram, I., Jemal, A., & Bray, F. (2021). Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 71(3), 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660

Svantesson, M., Carlsson, E., Prenkert, M., & Anderzén-Carlsson, A. (2016). ‘Just so you know, the patient is staff’: Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of caring for healthcare professional–patients. BMJ Open, 6(1), Article e008507. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008507

Thompson, C., & Yang, H. (2009). Nurses’ decisions, irreducible uncertainty and maximizing nurses’ contribution to patient safety. Healthcare Quarterly, 12, e178–e185. https://doi.org/10.12927/hcq.2009.20946

Vander Haegen, M., & Etienne, A.-M. (2018). Intolerance of uncertainty in parents of childhood cancer survivors: A clinical profile analysis. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 36(6), 717–733. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2018.1499692

Weaver, S. H., Cadmus, E., & Lindgren, T. G. (2018). Profile of the administrative supervisor: What do we know? Nurse Leader, 16(2), 134–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2017.11.007

Weiland, T. J., Mackinlay, C., & Jelinek, G. A. (2010). Perceptions of nurse practitioners by emergency department doctors in Australia. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 3, 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12245-010-0214-8

Williams I., Schliephake, K., Heinrich, L. & Baird, M. (2017). Integrating science and practice (iSAP): An interactive case-based clinical decision-making radiography training program [version 1]. MedEdPublish, 6, Article 65. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2017.000065

World Health Organization. (2024, May 3). Nursing and midwifery. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/nursing-and-midwifery

Zhang, S., Zhao, Z., Zhang, H., Zhu, Y., Xi, Z., & Xiang, K. (2023). Workplace violence against healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30, 74838–74852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-27317-2

Zhang, Y. (2017). Uncertainty in illness: Theory review, application, and extension. Oncology Nursing Forum, 44(6), 645–649. https://doi.org/10.1188/17.Onf.645-649

Media Attributions

- Fig 14.1 Portrait of James Bonnamy © Steve Wise is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

A Nurse Practitioner is a Registered Nurse with the education, experience, expertise and authority to diagnose and treat people of all ages with a variety of acute or chronic health conditions.

Evaluation of student learning at the end of a topic/unit/course. Summative assessments have high point value.

Refers to the period of time following a cancer diagnosis. Survivorship is about the health and wellbeing of the person living with and beyond cancer.

Cancer of the colon and/or rectum occurring in individuals younger than 50 years.