Chapter 7: Educational Theories that Inform Uncertainty Tolerance Teaching Practices and Learner Responses

Michelle D. Lazarus and Georgina C. Stephens

Learning Objectives

- Identify and briefly describe educational theories which relate to health professions learners’ uncertainty tolerance development.

- Relate the educational theories described in this chapter to your own practice and context.

- Identify strengths and limitations in the described educational theories as they relate to health professions learners’ uncertainty tolerance development.

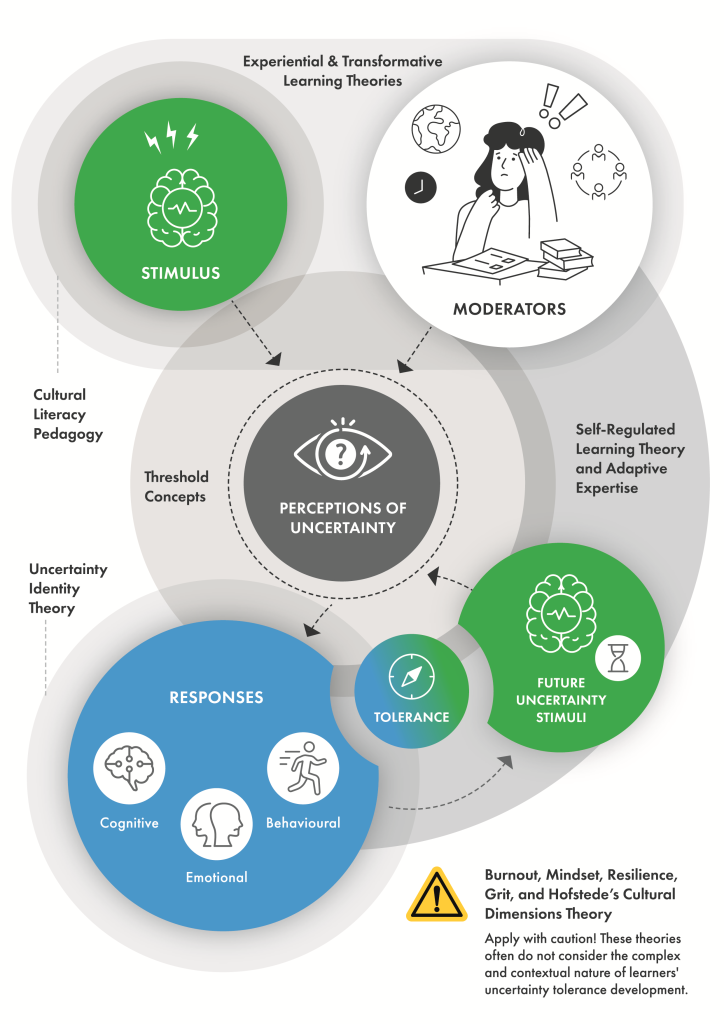

While the conceptual model of uncertainty tolerance (see Chapter 3) can be valuable as a framework for designing health professions educational activities, other learning and educational theories provide valuable insights to support these efforts. In addition to helping in the development of teaching activities, such theories can guide educators in the integration of uncertainty tolerance teaching practices across a whole unit or course, a curriculum, or a degree. They can also help educators better understand learners’ experiences and responses as they navigate the uncertainty built into the educational fabric. The theories discussed in this chapter include experiential learning theory, transformative learning theory, threshold concepts, cultural literacy pedagogy, uncertainty identity theory, and self-regulated learning theory (see Figure 7.1).

Additional theories – for example, about burnout, mindset, resilience and grit – may explain how individuals understand the world around them and how they approach challenges – of which uncertainty can be one. At a broader level, cultural dimensions theory can provide an explanation for how the culture and values of a society influence the behaviours of its members, including that society’s orientation towards the unknown. It may further contribute to our understanding of how learners and educators respond to uncertainty tolerance practices embedded in a curriculum.

Much of the literature around theories of resilience, grit, and mindset suggests that the individual is responsible for how much of a given construct they possess; therefore, application of such theories can be problematic. However, contemporary research in the field of uncertainty tolerance (as well as these other fields of study) is revealing the contribution of external factors to the manifestation of each construct within the individual. There is likely to be an interplay between the individual and the educational system that determines a learners’ uncertainty tolerance, capacity for a growth mindset, and so on – as opposed to the responsibility lying exclusively with either one or the other.

With this in mind, we provide descriptions of how the constructs of mindset, resilience, and grit may be seen as learner-centred flags which can provide signals to educators about which moderators to select and when as they consider integrating uncertainty in their educational practice. For instance, observations that learners appear ‘less resilient’ could prompt an educator to limit the extent to which uncertainty is purposefully stimulated, particularly if the learners are facing personal uncertainty (e.g., workforce shortages, high-stakes exams, or cost-of-living crises), or to consider selecting moderators that facilitate greater support for learners managing uncertainty (e.g., anonymity over responsibility for knowledge). Likewise, knowledge of learners’ cultural backgrounds may help to explain how their experiences have influenced their responses to uncertainty. It is important to remember, however, that societies are not homogenous, meaning there are considerable limitations to drawing on societal trends to understand individuals’ responses to uncertainty.

Importantly, the larger body of knowledge about uncertainty tolerance teaching practices suggests that learners are not solely responsible for or in control of their responses to uncertainty. There are contextual factors, and there may even be evolutionary factors, that impact responses, with some theories suggesting that a natural tendency to avoid uncertainty helped humans to escape danger as the species evolved (Lazarus, 2023). Given the entangled factors contributing to learners’ uncertainty tolerance, it is the responsibility of educators and institutions to engage the best-fit moderators to support learners’ uncertainty tolerance development.

Experiential Learning Theories

Theories of experiential learning focus on the role that meaningful experiences have in supporting learners to change their knowledge and behaviours (Kolb & Kolb, 2017). These theories underpin widely accepted learner-centred or active approaches in contemporary adult education, including problem-based learning, simulation, and workplace-based learning. Rather than simply experiencing events, however, experiential learning requires learners to must reflect on their experiences to understand how their developing knowledge may apply to future experiences (Kolb 1984). Consequently, experiential learning theories may help to explain why reflective learning seems to help with learning to manage uncertainty, as reflecting on uncertainty may allow learners to shift their understanding of the nature of uncertainty in healthcare and may alter learners’ responses to future experiences of uncertainty (Stephens et al., 2022a).

Experiential learning theory developed from the work of many educational scholars, including John Dewey (1938), Jean Piaget (1964), and Lev Vygotsky (1978). Among experiential learning theories, David Kolb’s experiential learning cycle is perhaps the best known and provides a model for the different stages of experiential learning (Kolb, 1984; Kolb & Kolb, 2017; Wijnen-Meijner et al., 2022). The four stages of Kolb’s experiential learning cycle are concrete learning, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation. Concrete learning occurs when a learner encounters a new experience or interprets a previous experience in a new way. Reflective observation involves the learner thinking about the experience. Abstract conceptualisation requires the learner to form new ideas or to adjust existing ideas based on the two initial stages of experience and reflection. Finally, active experimentation entails the learner applying their ideas to a new experience; this also represents the first stage in the second iteration of the cycle, which can repeat numerous times (e.g., until new learning or reinterpretation occurs) and can involve different durations of time.

When using Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning cycle, it is important to consider how learners’ new experiences relate to their prior experiences and learning (i.e., scaffolding of learning). Vygotsky’s (1978) zone of proximal development considers this aspect and is an important concept which can be drawn upon in experiential learning theory; it refers to the

distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers. (p. 86)

In other words, the zone of proximal development defines the space where a learner can perform a task only with the support of someone who is more knowledgeable (Gillespie et al., 2022; Kantar et al., 2020). Accordingly, the zone of proximal development represents the level at which a new experience should be pitched in order to continue learners’ development based on prior learning and highlights the importance of social interaction as an integral part of experiential learning (Kantar et al., 2020). Social interaction may involve educators but also peers and near-peers with greater knowledge and skills. Many of the moderators discussed in Chapter 5 (e.g., intellectual candour and pastoral care) could represent the support needed in this zone.

In health professions education, Vygotsky’s (1978) zone of proximal development underpins the ideas of safe struggle and safe fails, in which a learner is asked to undertake a task that is beyond their current capabilities but is supported by the presence of a more knowledgeable supervisor or mentor to ensure the task completion does not compromise patient safety (Gillespie et al., 2022). Critically, the task in a safe struggle is only just beyond a learner’s current capabilities, so it is realistically achievable. For example, a medical student who has already successfully learned basic suturing techniques on a foam model may be required to suture an actual wound during a supervised elective surgical procedure. Suturing a patient’s skin has greater complexity and higher stakes than suturing a model but should be within the medical student’s zone of proximal development. It may, however, be difficult for the medical student to determine the quality of their suturing and areas for improvement if they are not sufficiently supported by a more knowledgeable mentor, such as a surgeon or surgical resident.

Within the context of health professions education and uncertainty, experiential learning theory, including Kolb’s (1984) cycle and Vygotsky’s (1978) zone of proximal development, may be of relevance to curriculum design. For instance, experiential learning theory supports the need for health professions learners to repeatedly experience uncertainty relevant to their future careers in a scaffolded manner, with adequate support from others, and to engage in regular reflection on these experiences. This could involve uncertainty being purposefully introduced by educators early during a health professions program (e.g., through uncertain case-based learning, as described in Chapter 11 ), instead of educators attempting to withhold uncertainties until foundational knowledge is built. Furthermore, the active experimentation stage highlights the need for learners to trial different approaches to managing uncertainty over time, rather than educators simply providing a solution or approach to managing uncertainty. Although some learning about uncertainty may occur independently, Vygotsky’s (1978) zone of proximal development also highlights the importance of considering the roles of educators and near-peers in supporting learners to reach their full potential for managing uncertainty – aligning with educator-sourced moderators of uncertainty tolerance.

Transformative Learning Theory

Transformative learning (also known as transformation learning) theory is an educational theory typically applied to adults and explains how people adjust their perceptions of the world as they receive new information. The theory has a constructivist basis, wherein the learner constructs their own knowledge, building on knowledge they already have (Candy, 1989), rather than passively receiving knowledge as part of data transfer from teacher to learner (the latter is described as instrumental learning in transformative learning theory, representing the simplest type of learning). Often attributed in the literature to Mezirow (1991), transformative learning is described as a 10-step process where learners recast their point of view through a four-stage cycle of disorienting dilemma, critical reflection, rational dialogue, and action. Like Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning cycle and uncertainty tolerance conceptual modelling (see Chapter 3), transformative learning also emphasises the importance of reflective learning. Whereas Kolb focussed on learning through experience, transformative learning extends this to changing perspective, worldview, and identity.

The first stage of the transformative learning cycle involves presenting the learner with a disorienting dilemma, which can include challenging formerly held concepts and/or misconceptions (Mezirow, 1991, 1994). This is reminiscent of the defining characteristics of an uncertainty stimulus: an event which is complex, unknown, and/ or unpredictable (Hillen et al., 2017; Mezirow, 1994; Lazarus, Gouda-Vossos, Ziebell, et al., 2024). Essentially, what transformative learning theory can tell us about uncertainty tolerance teaching practices is that this first step, the disorienting dilemma, must be sufficiently challenging (i.e., uncertain) that learners are pushed to critically analyse assumptions they take for granted. An example related to uncertainty tolerance development might be a ‘pre-flection’ activity, such as that described by Brand et al. (2023) and in Chapters 9 and 17 (in press), where leaners’ assumptions about the people depicted in portraits are challenged.

Stimulating uncertainty alone, however, isn’t enough to lead to transformation of learners’ worldviews. Evidence suggests that stopping here could result in learner disengagement: Mezirow (1994, 2000) puts a great deal of weight on what factors (i.e., moderators of uncertainty tolerance) that have impacts on learners’ responses to the disorienting dilemma (i.e., the uncertainty stimulus).

The second stage of the transformative learning cycle includes critical reflection as a key moderating force which helps learners adapt to a new way of thinking. Learners reflect on troublesome knowledge (see the Threshold Concepts section later in this chapter) that is destabilising and consider this against their previous understanding. In the case of health professions education, an example of a disorienting dilemma could be experienced by learners when they are considering the biopsychosocial model of healthcare – in which the whole individual is considered in the treatment plan as opposed to simply giving the best treatment for the illness as if in a vacuum. This stage requires a review of current thinking alongside consideration of what actions to take in future similar situations. In transformative learning, learning is defined as the ‘social process of appropriating and construing a new or revised interpretation of an experience’ (Mezirow, 1991, 1994) which can then guide future action (Mezirow, 1994). Thus, transformative learning’s inclusion of critical reflection aligns with the strong evidence found in studies exploring uncertainty tolerance which have highlighted the valuable role that reflective learning has on moderating uncertainty tolerance. Relatedly, the ‘Model of Uncertainty Tolerance for Health Professions Learners’ (Chapter 3) includes a direct provision for critical reflection impacting future experiences with uncertainty.

The third stage in the transformative learning process is rational dialogue, in which the destabilised and reflective learner begins active communication with peers and educators to support their sense-making of this changing worldview. The second and third stages might be represented by a health professions learner exploring the different ways in which people work to support those living with mental illness. The learner may do this by talking with people who have experienced mental illness alongside their peers to discover what they think and by reaching out to mental health nurses, carers, psychologists, social workers, or psychiatrists. Through these interactions the learner who is engaged in the transformative learning process is likely to reconsider how they will act to support those with similar conditions in the future. This learning as discourse is often described in the transformative learning theory literature as communicative learning.

Rational dialogue may be enhanced through moderators identified in the uncertainty tolerance literature, such as teamwork and intellectual streaking or candour (Lazarus, Gouda-Vossos, Parasnis, et al., 2024). In the case of the learner reconsidering their role with patients who have experienced mental illness, it would be important for the professionals they consult to be transparent and open about the uncertainties they have faced in these roles.

Finally, the fourth stage requires action, referring to how the learner’s new, revised (constructed through the earlier stages of the cycle) guide their practice into the future, both immediate and longer term. Continuing with our example, this might be through a simulation or real encounter between the learner and a patient living with or who has experienced mental illness, giving the learner the opportunity to consider and apply their updated worldviews.

The transformative learning process may, based on the similarities identified above, provide an effective framework for considering uncertainty tolerance teaching practices across a unit or program of study (Lazarus, Gouda-Vossos, Ziebell, et al., 2024). For effective transformative learning to occur, educators need to engage in sufficiently destabilising practices but also to support learners as they make their way across this unstable ground. By providing opportunities for critical reflection, discourse through approaches such as teamwork, and practice of the new way of seeing the world as a health professions learner, transformative learning theory suggests that educators may be able to support learners in developing their uncertainty tolerance.

Threshold Concepts

Threshold concepts is an idea related to transformative learning theory. The threshold refers to learners being at the starting point of learning or a change to their worldview. The nature of threshold concepts is an element of ‘troublesome knowledge’. Threshold concepts, once managed, can transform learners’ thinking in a manner that cannot be ‘undone’ (i.e., learners cannot go back after crossing a threshold) (Meyer & Land, 2003): the way learners understand the world or concept is permanently changed. Threshold concepts can help educators engaging in uncertainty tolerance teaching practices to more deeply understand their learners’ experiences after an uncertainty stimulus is introduced.

An example of an uncertainty stimulus and threshold concept with relevance to health professions education is represented by professional identity development (Jones & Hammond, 2022) and understanding one’s professional role. It can be ‘troublesome’ learning to be responsible for the care of others and recognising that this isn’t always related to ‘curing a condition’. Consider a health professions learner caring for a patient who is nearing the end of their life, which may mean supporting the person with dignity, kindness, and a focus on pain management as opposed to using interventions intended to prolong life. The administered medicines and dosing in this context could result in harm to a patient in other contexts, leading to the troublesome knowledge that the effect of a particular medication could be either beneficial or detrimental, depending on the context. The threshold is crossed as the learner lives through this experience and begins to recognise that the role of a healthcare professional is diverse and not as rigid as they may have previously thought. This crossing of the threshold may be challenging and a struggle when the first such patients are encountered, but becomes a permanent part of the learner’s identity once crossed.

Jan Meyer and Ray Land (2005) are credited with developing the framework for threshold concepts, which may guide educators in steps and considerations related to transformational learning and managing uncertainty stimuli. Meyer and Land attribute seven key features to threshold concepts: they are transformative, irreversible, troublesome, integrative, bounded, discursive, and reconstructive. Many of these features point to an identity shift in the learner that becomes part of the person once managed. To reiterate, once the learner manages a threshold concept, they are forever changed and will no longer see the world in the way they once did.

The troublesome part of threshold concepts seems to have the greatest relevance with understanding uncertainty tolerance in learners. Arguably, it is the troublesome knowledge that is the start of managing a threshold concept. Troublesome knowledge can be the disorienting dilemma described by Mezirow (1991, 1994) or the uncertainty stimulus such as those described in Chapter 3. The uncertainty stimulus / troublesome knowledge propels the learner into what Meyer and Land (2005) term the ‘liminal space’, which is the ‘space between’. In the context of uncertainty tolerance, this is the space between knowns / certainty and unknowns / uncertainty. The liminal space is destabilising, because the learner is placed in wholly unfamiliar territory, teetering between comfort and discomfort, between what was and what is. According to threshold concepts, a learner who experiences an uncertainty stimulus – something ‘alien’ or ‘counter-intuitive’ (Meyer & Land, 2003, 2005) – can teeter in this in between liminal space forever. However, in doing so – in not actively progressing towards the unfamiliar, uncertain, and unknown – they are creating a psychological challenge for themselves, because this is a necessary step for progression. The goal, therefore, is for educators to be aware when learners have entered a liminal space and to support and guide them through it. In the case of supporting learners to manage their responses to uncertainty stimuli, educators can draw on moderators within their control, discussed in Chapter 5 .

There are several similarities between teaching practices which support learners’ uncertainty tolerance development and those supporting learners’ management of threshold concepts. For instance, grey cases appear to resemble the ‘real-world’ questions discussed by Meyer and Land (2003, 2005) for stimulating uncertainty and encountering troublesome knowledge. Reflective learning (discussed in Chapter 3 ) may help learners to recognise and address threshold concepts. The language used to describe threshold concepts is also similar to the language used by learners discussing their experiences with uncertainty, as noted by Lazarus, Gouda-Vossos, Parasnis, et al. (2024, p. 187):

Even the descriptors of how learners respond as they traverse the ‘liminal space’ of TC [ threshold concepts] are strikingly similar to those used by learners who are managing uncertainty in their educational endeavours. Land et al. (2014) describe how learners within the liminal space may ‘give up’ and become frustrated, missing the familiar place in which they started (Land et al., 2014). The UT [uncertainty tolerance] conceptual model similarly describes negative behavioural responses to uncertainty as ‘avoidance and inaction’ alongside cognitive and emotional descriptors such as ‘threat, doubt and worry, fear and despair’ (Hillen et al., 2017), mirroring descriptions identified in HE [higher education] learner populations (Lazarus et al., 2022; Stephens et al., 2021; Stephens et al., 2022b). Together, this evidence illustrates that uncertainty tolerance may provide a framework for supporting individual’s management of TC.

Threshold concepts can help educators engaged in uncertainty tolerance teaching practices by normalising the discomfort learners may experience when faced with an uncertainty stimulus and providing a language and series of steps to manage this uncertainty. From this perspective, threshold concepts illustrate the transformation learners will experience once they make it through a liminal space – with the help of well-thought-out educator-sourced moderators.

Cultural Literacy Pedagogy

Cultural literacy pedagogy seeks to develop learners’ skills and knowledge for understanding cultural differences and drawing meaning from this awareness (García Ochoa & McDonald, 2020, Chapter 1). It is quite distinct from cultural expertise, which focusses on reductionist categorisation of cultures and knowledge of these groups (Dogra & Carter-Pokras, 2019). At first glance, the term cultural literacy pedagogy may seem unrelated to health professions learners’ development of uncertainty tolerance. However, there is some evidence that the methods that foster cultural literacy also foster uncertainty tolerance development. Cultural literacy pedagogy relies on an experiential learning spectrum (García Ochoa & McDonald, 2019) which can provide a framework for understanding how and when to introduce uncertainty stimuli across a degree or course.

The experiential learning spectrum of cultural literacy pedagogy has three main components: critical incidents, destabilisation, and iso-immersion. Each of these stages carries with it a different set of uncertainty stimuli. The critical incidents stage is the least experiential and aligns most closely with grey cases and transferring learning uncertainty stimuli. A learner applies textbook knowledge to curated real-world cases, which allows them to practise managing uncertainty by reflecting on their experiences as they journey through the cases. This stage ‘provides learners with a preliminary exposure to uncertainty and an opportunity to pause, pay attention, reflect and practise thinking through their responses to realistic cultural contexts’ (Lazarus et al., in press). Of the three stages of cultural literacy pedagogy, critical incidents has the narrowest focus on uncertainty stimuli. The stimuli are primarily related to the case unknowns, though there may be some additional sources of uncertainty if learners work in diverse teams to approach cases.

The purpose of the destabilisation stage is ‘for students to understand how they approach and react to uncertainty’ (i.e., what actions they take when they do not yet know or have not yet experienced the situation or context), with the goal of prompting ‘introspection at a very fundamental level’ (García Ochoa et al., 2016, p. 550). Destabilisation most closely resembles simulation or acting out career-based uncertainty cases in which the learning takes place in a psychologically safe and controlled context. While critical incidents rely on reflection and thinking or talking about the knowns and unknowns of the case, destabilisation requires the learner to participate while managing this more complex environment. Because of the addition of hands-on participation, the sources of uncertainty extend from the case itself to how the actors will work through the case. In this way, the destabilisation phase focusses on embodied management of uncertainty. For successful engagement of destabilisation, cultural literacy pedagogy suggests that debriefing is critical. Following on from the destabilisation (e.g., simulation) exercise, there should be provision to reflect on the experience, clarify knowledge, discuss motivation behind actions, and identify ways to enhance future similar experiences. The goal of this stage is for learners to recognise what their perceptions and reactions tend to be and for educators to support them to potentially enhance these actions or adjust them, depending on the outcome (García Ochoa & McDonald, 2019).

Iso-immersion is the most experiential aspect of cultural literacy pedagogy and is described as offering a sink-or-swim approach. Learners are placed in a ‘real-life’ environment (e.g., clinical placements) and must contend with the numerous sources of uncertainty in the situations they face, including the people they encounter, and the system they are working within – here, the sources of uncertainty experienced can be immeasurable.

While some training starts with learners in iso-immersion, for health professions education, iso-immersion often occurs later in a program (e.g., there is an early preclinical phase followed by clinical years or placement blocks), or, when early placements are used, uncertainty is typically bounded to protect patients (e.g., learning is focussed on initial observation of healthcare professionals, with active involvement in patient care slowly increased as knowledge and skills develop). Learners can practise using the tools they have developed through the initial two cultural literacy pedagogy stages and consider what adaptations are needed in the healthcare environment. Later-stage learners may have moderators (e.g., prior experiences) which allow them to more readily manage the numerous uncertainty stimuli present in this stage.

Cultural literacy pedagogy can help educators identify steps to prepare the learning environment for learners to adaptively respond to uncertainty by raising learners’ awareness of the sources of uncertainty in these contexts. Furthermore, cultural literacy pedagogy can help with curriculum planning and programmatic uncertainty tolerance pedagogy implementation by providing a guiding framework for these across a degree. For instance, a spiral curriculum approach could be taken, in which key uncertainty stimuli that health professions learners will encounter during healthcare practice are spaced across a program with increasing difficulty and sources of uncertainty at each encounter. By working through the cultural literacy pedagogy stages in a spiral curriculum, learners may be able to build on prior skills in a manner that is applied to different contexts.

Uncertainty Identity Theory

Uncertainty identity theory is valuable when considering how learners are likely to respond to uncertainty tolerance pedagogy. Described by Hogg and Adeleman in 2013, this ‘theory suggests that when faced with high levels of uncertainty about our identities, we seek to suppress the [accompanying] discomfort by finding ways to fit in’ (Lazarus, 2023, p. 204). In the learning context, this could mean that learners familiar with excelling in schools, in which teacher-led educational approaches are common, are more likely to question themselves, their identities, and their roles and approaches to learning in educational contexts that are less familiar (i.e., more uncertain). For instance, a learner who has made it to university by engaging in rote learning and excelling at single correct answer exams may struggle with their identity when faced with more open-ended, flexible assessments. Uncertainty identity theory suggests that the response in such contexts may be to double-down on aspects of their life perceived as certain. This may mean persisting with the learning approaches that worked before but are less useful now, as the learner sits in a state of denial. The learner could appear frustrated with the educator or the content when it is uncertain, or they may fully disengage from the learning process. Recognising these maladaptive responses to uncertainty, and the relationship between them and the learners’ identity uncertainty, can help educators support learners to adapt.

Educators who acknowledge the discomfort that a novel learning environment brings and who provide a sense of purpose in the uncertain learning process can support learners as they discover their changing identity. Key elements in successfully helping learners to manage such identity shifts are psychological safety and a supportive learning environment. For instance, if a learner is struggling to engage in self-directed learning, the educator can encourage them to try out a solution, and then point to the strengths of that approach. If a learner is veering off course, the educator could guide them back towards the right path by encouraging their process but redirecting their knowledge chain by asking whether they have tried the appropriate resource. It is vital for the educator to recognise, in this situation, that the learner may be struggling not only with the assignment but also with who they are (i.e., their personal identity). The educators’ response should be gentle and provide supportive guidance without judgement or punishment. The goal is to help learners become curious about who they are to support their exploration of the best ways to learn.

Self-Regulated Learning Theory & Adaptive Expertise

Due to the inherent nature of uncertainty in healthcare (Chapter 1), even experts face uncertainties (Han et al., 2011; Simpkin & Armstrong, 2019). In the educational literature, two types of expertise are described which differ according to how they manage novel, complex, and uncertain situations. Routine expertise is found in those possessing a high level of knowledge and skills in a particular domain and who stay within defined domain boundaries (Pelgrim et al., 2022). Examples include highly skilled technicians or artisans who perform duties only within their skillset. Routine expertise may continue to develop as further experience is gained (e.g., by becoming more efficient and accurate when practising skills), but it typically does not extend in new directions. In contrast, those with adaptive expertise can apply their knowledge and skills in changing, novel, or complex situations through creativity, innovation, and improvisation (Lajoie & Gube, 2018; Pelgrim et al., 2022). This relies on a deep understanding of not just how to manage scenarios but also the evidence that supports such management, and where limitations in the evidence may exist (Pelgrim et al., 2022). It is this depth of understanding that can allow an adaptive expert to think critically, transfer knowledge, and even ‘break the rules’ to achieve an outcome. Hence, adaptive expertise, rather than routine expertise, is particularly relevant to managing healthcare uncertainties and to developing health professions learners’ uncertainty tolerance by providing a framework for successfully managing uncertainty after achieving expert status.

The differences between routine and adaptive expertise within the context of healthcare are illustrated by the respective roles of non-physician cataract surgeons and ophthalmologists. Non-physician cataract surgeons are trained to perform cataract surgery in regions underserved by ophthalmologists (i.e., doctors who specialise in the medical and surgical treatments of eye conditions) (Fortané et al., 2019). They perform and focus exclusively on cataract surgery, with generally excellent results. This contrasts with the diverse skillset and expertise of ophthalmologists, who treat and manage diverse conditions and undertake procedures related to the eye. Non-physician cataract surgeons may be considered routine experts, whereas ophthalmologists may be considered adaptive experts.

Self-regulated learning theory, and a related concept known as the ‘master adaptive learner’, provides a model for how to progress from novice health professions learner to adaptive expert. Self-regulation is defined as the ‘self-generated thoughts, feelings, and actions that are planned and cyclically adapted to the attainment of personal goals’ (Zimmerman, 2000, p. 14). Drawing on the work of Bandura (1986), self-regulation involves learners actively managing their context to promote attainment of learning goals (Sandars & Cleary, 2011).

Self-regulation occurs in a cycle, typically consisting of three stages: before or forethought, during or performance, and after or self-reflection (Sandars & Cleary, 2011). The before stage involves setting learning goals and may include learners proactively preparing for learning tasks (e.g., reading on a topic before attending a formal learning activity and identifying learning opportunities aligned with the goal). Goals may be process oriented (i.e., focussed on steps and learning strategies) or outcome focussed (i.e., the final product of learning). During the learning, self-regulated learners may seek to control their thoughts and behaviours by adjusting their environment and engaging in actions intended to enhance learning performance – for example, minimising distractions (e.g., visiting a quiet study space and muting social media notifications) and using evidence-based learning approaches (e.g., concept mapping and focussed work followed by short breaks). The after stage involves evaluation of whether learning goals were achieved and, if not, identifying factors that may have contributed to this. The cycle can then repeat with adjustments and adaptations based on self-reflection.

Research shows that those who engage with self-regulated learning are more likely to have higher academic performance than those who don’t (Sandars & Cleary, 2011). The ability to self-regulate learning is especially pertinent for healthcare professionals, for whom there is a relative lack of formal learning structures in learning and working contexts. For instance, workplace-based learning (e.g., clinical placements) typically requires learners to navigate uncertainties in how to most effectively learn when the primary goal of the workplace is the work (e.g., patient care) rather than learning (Stephens et al., 2022b). Following the conclusion of their formal education and training, healthcare professionals also need to engage in continued learning across their careers. Self-regulation of learning can assist learners along the path to adaptive expertise – a process also referred to as the master adaptive learner model (Smith, 2020).

Berkhout et al (2015) describes mechanisms to support educators’ in facilitating learners’ engagement in self-regulation. Providing initial direct instruction about the stages of self-regulation and study strategies may aid learners, particularly when they are transitioning from contexts with more teacher-led or external regulation of learning. Educators can also encourage self-regulation through feedback dialogues, especially when learners and educators work together to reflect on performances and develop strategies for improving subsequent performances. Feedback can help learners to identify where they are in the learning journey, as self-assessment is often inaccurate. The Dunning–Kruger effect occurs when learners have a high level of confidence but a low level of competency – in essence, when they are unaware of the extent of learning yet to be achieved (Kruger & Dunning, 1999). Feedback dialogues may thus aid learners to understand the limitations of their knowledge and skills, and the implications of this in the context of patient care. Fostering student engagement with feedback can be challenging but is enhanced when trust is built between the learner and the educator (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). Trust can be difficult to establish in a one-off feedback encounter, so longitudinal mentorship relationships may be needed to further aid self-regulated learning (Singh, 2018).

Because self-reflection is the third stage in the self-regulated learning cycle, opportunities for reflective learning in curricula may also assist learners to engage in self-regulation. As with self-regulated learning itself, learners may require initial instructions and feedback on how to engage in self-reflection (Stephens et al., 2022a; Stephens & Lazarus, 2024). Learners might use the What? So what? Now what? framework for self-reflection (Academy of Medical Royal Colleges et al., n.d., p. 5.). The framework prompts learners to describe an experience (what?), to explore its importance and meaning for learning (so what?), and to consider what can be learned or changed going forward (now what?). To aid critical engagement with reflection, reflective learning activities should ideally be formative tasks rather than graded assessments, as grading can result in learners presenting ‘idealised’ scenarios rather than those most useful for learning (Sandars, 2009).

If an educator perceives that their learners lack skills for self-regulated learning, they should not consider this to be the fault of the learners. Rather, they should identify strategies to enhance learners’ self-regulation, such as direct instruction on learning approaches, feedback dialogue, and opportunities for reflective learning. Approaches may ultimately facilitate life-long learning and the development of the adaptive expertise required to manage uncertainty.

Theories to Engage with Caution

The theories discussed above may be helpful for educators in designing educational activities and curricula that could holistically influence learners’ uncertainty tolerance development. The group of theories introduced in this section are often mentioned in discussions of uncertainty tolerance, but they tend to have a greater focus on individual learners and their attributes. Relying on such theories for explaining and supporting learner uncertainty tolerance can be problematic because of the complex and interdependent relationship between one’s uncertainty tolerance and the context within which it occurs. Accordingly, the following theories should be considered as signals (Figure 7.1) to educators that uncertainty stimuli and moderators may need to be adjusted to meet learners’ needs as they manage educational uncertainty.

Resilience

Resilience is a person’s ability to positively adapt and overcome difficulties: to ‘bounce back’ in some degree following negative experiences (Lin et al., 2019). Although definitions vary, elements of resilience include the ability to accept reality and the capacity to find meaning and improvise when faced with challenges (Coutu, 2002). In health professions education research generally, resilience has been described as protective against perceived stress and burnout and associated with compassion and personal meaning in patient care (Cooke et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2019). In relation to uncertainty tolerance, reduced resilience has been associated with lower measured uncertainty tolerance, suggesting that a lack of resilience negatively affects one’s ability to manage uncertainty (Cooke et al., 2013; Simpkin et al., 2018).

Despite these links, gaps remain in understanding the determinants of resilience: studies focussed on linking resilience with sociodemographic factors have yielded mixed findings (de Oliveira et al., 2017; Southwick et al., 2014). As research into the development and determinants of resilience continues, educators who perceive a lack of resilience among learners may draw on uncertainty tolerance moderators that relate to aspects of resilience. For example, the ability to find meaning when faced with the challenge of an uncertainty stimulus may be enhanced by asking learners to identify a sense of purpose. Educators may also benefit from reviewing the ways in which learners face difficulty and whether these factors are modifiable.

Considering the difficulties that health professions learners face in each context is also important for understanding an individual’s level of resilience. Should a learner face severe, repeated, or sustained difficulties (e.g., because either the system or the individual lacks the necessary resources), they could appear to lack resilience, when in fact their ability to bounce back is being impeded by the situation they are in. Further examples include learners who experience bullying and discrimination, which are unfortunately substantial problems in health professions education (Álvarez Villalobos et al., 2023), and learners who have fewer social supports than their peers (Liu & Cao, 2022). A claim of low resilience in learners who are experiencing bullying or discrimination may be used to excuse the behaviours of perpetrators; therefore, low resilience may better serve as a flag for educators to explore why a learner seems less able to overcome a challenge (e.g., managing educational uncertainty).

Grit

Grit is an individual’s ‘perseverance and passion for long-term goals’ (Duckworth et al., 2007a, p. 1087) Like research into uncertainty tolerance, research into grit has a substantive focus on scale development as a means of measuring the construct (Duckworth et al., 2007b; Duckworth & Quinn, 2009). Based on such scales, higher levels of grit are associated with higher levels of education and fewer career changes (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009). Specifically, within health professions education, higher levels of grit are associated with protection from burnout. Although lower uncertainty tolerance is associated with burnout risk (Hancock & Mattick, 2020), the single study which explored both grit and uncertainty tolerance did not identify a statistically significant association (Jumat et al., 2020). Perseverance more generally is described in the uncertainty tolerance literature as a positive behavioural response to uncertainty (Stephens et al., 2021).

Although theoretically grit may provide impetus for an individual to persevere in managing uncertainty encountered in the pursuit of their long-term goals, the construct has also been problematised, as it is perhaps less aligned with managing changes to initial goals as circumstances and contexts evolve. An example is found in the moving goal posts of post-graduate training for medical practitioners. The Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (2023) recently capped the number of times a person can apply to several surgical training programs; previously, this was open-ended. So, although grit may have enabled some to indefinitely pursue their long-term goal of becoming a subspecialty surgeon, this is no longer possible in the Australian context. Quitting the pursuit of a goal may be considered the antithesis of grit; however, quitting may also open opportunities that a hyper-focussed pursuit of the original goal would inhibit. Hence, ‘less grit, more quit’ is described as potentially beneficial, as quitting may help a learner to adapt to the changing context they find themselves in (Morgan, 2021), rather than unwaveringly pursing a goal that no longer aligns with their best interests.

Due to the inherent uncertainty related to careers in health professions (Stephens et al., 2022b), assisting learners to identify multiple possible career paths may be more helpful than encouraging rigid adherence to a single goal to the exclusion of all other opportunities. As with the facilitation of resilience described above, it may be beneficial for educators to help learners identify a sense of purpose (e.g., a motivation that aligns with their personal values, which tend to be stable over time) and to consider how this might guide them towards aligned long-term goals (Stephens et al., 2022a).

Burnout

Burnout is considered a psychological syndrome that occurs in response to chronic interpersonal job-related stressors and comprises three key dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and reduced personal accomplishment (Maslach & Leiter, 2016). Studies of healthcare professionals describe burnout as having reached epidemic proportions (American Medical Association, 2023). Hancock & Mattick(2020) reviewed the uncertainty tolerance literature and found numerous studies linking higher burnout risk with medical students and doctors who have lower uncertainty tolerance. They theorised that low uncertainty tolerance may predispose individuals to burnout, but the nature of the relationship between burnout and uncertainty tolerance remains unclear.

Importantly, the conceptualisation of burnout has shifted over time, from the view that it results from a problem with how an individual copes with job-related stressors (perhaps related to a lack of resilience or grit) to the idea that it is a multifaceted occupational syndrome caused by workplace and structural factors, such as insufficient resources, including time and personnel (Demerouti et al., 2021). This shift in understanding of burnout also reflects changes in the conceptualisation of uncertainty tolerance (see Chapter 3). If educators perceive that learners are burned out, the approach should be to understand the stressors and uncertainty stimuli learners are facing and the moderators currently at play. It may be the case that uncertainty extraneous to learning can be reduced (e.g., by providing an orientation for work-integrated learning) or resources adjusted (e.g., further time for or spacing out of assessments) (Stephens et al., 2022a).

Mindset Theory

Mindset theory developed from research into the impact of an individual’s beliefs on their intelligence, learning, and development (Dweck & Leggett, 1988). The resulting theory, developed by Carol Dweck (2006), posits that mindsets exist on a continuum from fixed to growth. The concept of growth mindset developed from the idea that some individuals are ‘mastery oriented’ and the belief that human capacities can be developed over time. Aligned with a growth mindset is the acceptance that mistakes and failures provide learning opportunities and can lead to mastery. The concept of fixed mindset developed from the ‘helpless’ response and the belief that human capacities are inherent and static. Learners with a fixed mindset may view mistakes as exposing their inherent limitations.

Although mindset theory has influenced educational practices since the 1980s, its application to health professions education has expanded considerably since the 2010s (Memari et al., 2024; Williams & Lewis, 2021). Growth mindset is associated with academic achievement, and the focus on mastery may provide an impetus to manage uncertainty in learning (Babenko et al., 2019). Because of the beneficial associations made with growth mindset, health professions have sought to identify ways to foster its development. The educational approaches described as fostering a growth mindset include those also known to foster uncertainty tolerance, such as reflective learning and providing expert guidance with actionable feedback.

Despite substantive interest in mindset theory in health professions education, and although cultivating a growth mindset may help health professions learners to learn from uncertainty, the theory has attracted some controversy. Firstly, studies of mindset theory and education (e.g., links between mindset and academic performance, and the impacts of mindset interventions) have demonstrated heterogeneous results (Yeager & Dweck, 2020). Furthermore, mindset theory is commonly misunderstood, a phenomenon known as false growth mindset (Memari et al., 2024, p. 262). Educator misconceptions include the belief that learners have either a fixed or a growth mindset and that the onus is on learners themselves to ‘correct’ their mindset. Rather, mindset theory emphasises that an individual’s mindset depends on context and that there are approaches educators can take to foster growth mindset in their learners. As with the concepts of resilience and grit, if a learner is perceived to have a fixed mindset that impairs their ability to learn to manage uncertainty, educators should firstly consider why a fixed mindset may have developed and the contextual factors that may have influenced it. For health professions learners, a major contextual factor that could cultivate a fixed mindset is the experience of high-stakes graded assessments.

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions Theory

So far in this chapter, we have focussed on theories that can inform how an individual learns to manage uncertainty. By contrast, Hofestede’s cultural dimensions theory helps to explain generalised responses to uncertainty across a society. It results from extensive research in the context of business by social psychologist Geert Hofstede (Hofstede 2001; Hofstede et al., 2010) and describes the effects a society’s culture can have on the values and behaviours of its members. The theory characterises a society’s culture according to six dimensions: power distance, individualism versus collectivism, masculinity versus femininity, uncertainty avoidance, long-term versus short-term orientation, and indulgence versus restraint. Among these, uncertainty avoidance has the greatest relevance to uncertainty tolerance.

In Hofstede’s theory (2001, 2010), uncertainty avoidance is defined as the degree to which individuals in a society avoid or feel uncomfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity. In other words, uncertainty avoidance is synonymous with the construct of uncertainty tolerance, although the former is framed negatively and the latter positively (Hillen et al., 2017), but the concept is applied to trends across a society.

Monrouxe et al. (2022) applied the cultural dimensions theory to the context of health professions education in an international survey of medical students which used a scale to measure each cultural dimension. They discovered that of all the cultural dimensions, uncertainty avoidance showed the greatest geographical variation. Groups found to have higher levels of uncertainty avoidance included those from China, Taiwan, Indonesia, and Malaysia, and groups with lower uncertainty avoidance included those from Israel, Australia, Ireland, and New Zealand. The study also found some variation according to gender; for instance, results for South Korean males indicated a high uncertainty avoidance, whereas results for South Korean females indicated a medium uncertainty avoidance.

These types of findings may help educators to broadly understand the potential impact of uncertainty tolerance teaching practices in a particular context. For example, cohorts in settings with higher uncertainty avoidance may need greater support when they encounter uncertainty tolerance teaching practices. It is important to mention, however, that individuals within a single culture may vary considerably in their individual levels of uncertainty tolerance, due to different experiences and exposures to moderators. Therefore, this theory can generate a broad sweeping generalization about potential learner responses to uncertainty, but personalized learning – where the educator observes individual learners’ responses to uncertainty – is likely to be more valuable.

Examples

This section provides examples of how the educational theories discussed above may be applied when considering uncertainty in health professions education. Click through the slides below to learn more.

Review & Reflect

End of Chapter Review

This exercise allows you to consider the relationship between uncertainty tolerance and theories which can influence learning.

Reflection

Reflect on your educational activities. This could include your experiences in developing and delivery of the activity, or in supporting learners as they engage in the activity. Use the following questions to guide your thinking.

- To what extent do you engage educational theories in the development of learning activities? List the educational theories you currently draw on and explain how they impact the learning environment.

- Which educational theories are you less familiar with but interested in? Relate the theory to an existing learning activity and describe how you could apply the theory to better understand your health professions learners’ experiences of uncertainty.

- How could you revise your learning activity to more effectively integrate your chosen theory? How might this impact learners’ experiences of uncertainty?

You may find it helpful to write down or record your responses to these questions before moving on to the next section, which describes exemplar activities that may be used to prepare learners for managing uncertainty.

References

Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, UK Conference of Postgraduate Medical Deans, General Medical Council, & Medical Schools Council. (n.d.). The reflective practitioner: Guidance for doctors and medical students. General Medical Council. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/dc11703-pol-w-the-reflective-practioner-guidance-20210112_pdf-78479611.pdf

Álvarez Villalobos, N. A., De León Gutiérrez, H., Ruiz Hernandez, F. G., Elizondo Omaña, G. G., Vaquera Alfaro, H. A., & Carranza Guzmán, F. J. (2023). Prevalence and associated factors of bullying in medical residents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Health, 65(1), Article e12418. https://doi.org/10.1002/1348-9585.12418

American Medical Association (2023, February 16). What should be done about the physician burnout epidemic. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/what-should-be-done-about-physician-burnout-epidemic

Babenko, O., Daniels, L. M., Ross, S., White, J., & Oswald, A. (2019). Medical student well-being and lifelong learning: A motivational perspective. Education for Health, 32(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.4103/efh.EfH_237_17

Bandura A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

Berkhout, J. J., Helmich, E., Teunissen, P. W., van den Berg, J. W., van der Vleuten, C. P., & Jaarsma, A. D. (2015). Exploring the factors influencing clinical students’ self-regulated learning. Medical Education, 49(6), 589–600. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12671

Brand, G., Wise, S., Bedi, G., & Kickett, R. (2023). Embedding Indigenous knowledges and voices in planetary health education. The Lancet Planetary Health, 7(1), e97–e102. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00308-4

Candy, P. C. (1989). Constructivism and the study of self-direction in adult learning. Studies in the Education of Adults, 21(2), 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.1989.11730524

Cooke, G., Doust, J. A., & Steele, M. C. (2013). A survey of resilience, burnout, and tolerance of uncertainty in Australian general practice registrars. BMC Medical Education, 13, Article 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-13-2

Coutu, D. L. (2002). How resilience works. Harvard Business Review, 80(5), 46–55.

de Oliveira, A. C., Machado, A. P., & Aranha, R. N. (2017). Identification of factors associated with resilience in medical students through a cross-sectional census. BMJ Open, 7(11), Article e017189. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017189

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Peeters, M. C., & Breevaart, K. (2021). New directions in burnout research. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 30(5), 686–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2021.1979962

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Macmillan.

Dogra, N., & Carter-Pokras, O. (2019). Diversity in medical education. In T. Swanwick, K. Forrest, & B. C. O’Brien (Eds.), Understanding medical education: Evidence, theory, and practice (3rd ed., pp. 513–529). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119373780.ch35

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007a). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087–1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007b). Grit Scale [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t07051-000

Duckworth, A. L., & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the short grit scale (Grit-S). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802634290

Dweck, C. S. & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social–cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

Fortané, M., Bensaid, P., Resnikoff, S., Seini, K., Landreau, N., Paugam, J.-M., Nagot, N., Mura, T., Serrand, C., Villain, M., & Daien, V. (2019). Outcomes of cataract surgery performed by non-physician cataract surgeons in remote North Cameroon. The British Journal of Ophthalmology, 103(8), 1042–1047. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-312428

García Ochoa, G., & McDonald, S. (2019). Destabilisation and cultural literacy. Intercultural Education, 30(4), 351–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2018.1540112

García Ochoa, G., & McDonald, S. (2020). Cultural literacy and empathy in education practice. Palgrave Macmillan.

García Ochoa, G., McDonald, S. & Monk, N. (2016). Embedding cultural literacy in higher education: A new approach. Intercultural Education, 27(6), 546–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2016.1241551

Gillespie, H., Reid, H., Conn, R., & Dornan, T. (2022). Pre-prescribing: Creating a zone of proximal development where medical students can safely fail. Medical Teacher, 44(12), 1385–1391. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2022.2098100

Han, P. K., Klein, W. M., & Arora, N. K. (2011). Varieties of uncertainty in health care: A conceptual taxonomy. Medical Decision Making, 31(6), 828–838. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989×11393976

Hancock, J., & Mattick, K. (2020). Tolerance of ambiguity and psychological well-being in medical training: A systematic review. Medical Education, 54(2): 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14031

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Hillen, M. A., Gutheil, C. M., Strout, T. D., Smets, E. M., & Han, P. K. (2017). Tolerance of uncertainty: Conceptual analysis, integrative model, and implications for healthcare. Social Science & Medicine, 180, 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.024

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Sage.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind; Intercultural cooperation and its importance for survival (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Hogg, M.A. & Adelman, J. (2013). Uncertainty–identity theory: Extreme groups, radical behavior, and authoritarian leadership. Journal of Social Issues, 69, 436-454. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12023

Jones, H., & Hammond, L. (2022). Threshold concepts in medical education: A scoping review. Medical Education, 56(10), 983–993. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14864

Jumat, M. R., Chow, P. K., Allen, J. C., Lai, S. H., Hwang, N. C., Iqbal, J., Mok, M. U., Rapisarda, A., Velkey, J. M., Engel, D. L., & Compton, S. (2020). Grit protects medical students from burnout: A longitudinal study. BMC Medical Education, 20, Article 266. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02187-1

Kantar, L. D., Ezzeddine, S., & Rizk, U. (2020). Rethinking clinical instruction through the zone of proximal development. Nurse Education Today, 95, Article 104595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104595

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall.

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2017). Experiential learning theory as a guide for experiential educators in higher education. Experiential Learning & Teaching in Higher Education, 1(1), Article 7. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/elthe/vol1/iss1/7/

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

Lajoie, S. P., & Gube, M. (2018). Adaptive expertise in medical education: Accelerating learning trajectories by fostering self-regulated learning. Medical Teacher, 40(8), 809–812. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1485886

Lazarus, M. D. (2023). The uncertainty effect: How to survive and thrive through the unexpected. Monash University Press.

Lazarus, M. D., Garcia Ochoa, G., Truong, M., & Brand, G. (in press). Uncertainty tolerance teaching practices and cultural literacy pedagogy. In J. Brady & J. Gingras (Eds.), Advancing social justice teaching in the health professions through interdisciplinary approaches. University of Regina Press.

Lazarus, M. D., Gouda-Vossos, A., Parasnis, J., Davis, E. A., Mujumdar, S., Ziebell, A., & Brand, G. (2024). The human element: How educators can prepare learners for future workplace uncertainties and troublesome knowledge. In J. P. Davies, E. Gironacci, S. McGowan, A. Nyamapfene, J. Rattray, A. M. Tierney, & A. S. Webb (Eds.), Threshold concepts in the moment (pp. 186–208). Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004680661_013

Lazarus, M. D., Gouda-Vossos, A., Ziebell, A., Parasnis, J., Mujumdar, S., & Brand, G. (2024). Mapping educational uncertainty stimuli to support health professions educators’ in developing learner uncertainty tolerance. Advances in Health Sciences Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-024-10345-z

Lin, Y. K., Lin, C.-D., Lin, B. Y.-J., & Chen, D.-Y. (2019). Medical students’ resilience: A protective role on stress and quality of life in clerkship. BMC Medical Education, 19, Article 473. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1912-4

Liu, Y., & Cao, Z. (2022). The impact of social support and stress on academic burnout among medical students in online learning: The mediating role of resilience. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, Article 938132. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.938132

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20311

Memari, M., Gavinski, K., & Norman, M. (2024). Beware false growth mindset: Building growth mindset in medical education is essential but complicated. Academic Medicine, 99(3), 261–265. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000005448

Meyer, J. H., & Land, R. (2003). Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge: Linkages to ways of thinking and practising within the disciplines. In C. Rust (Ed.), Improving student learning theory and practice: ten years on (pp. 412–424). Oxford Centre for Staff & Learning Development.

Meyer, J. H., & Land, R. (2005). Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge (2): Epistemological considerations and a conceptual framework for teaching and learning. Higher Education, 49, 373–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-6779-5

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (1994). Understanding transformation theory. Adult Education Quarterly, 44(4), 222–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/074171369404400403

Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. Jossey-Bass.

Monrouxe, L. V., Chandratilake, M., Chen, J., Chhabra, S., Zheng, L., Costa, P. S., Lee, Y.-M., Karnieli-Miller, O., Nishigori, H., Ogden, K., Pawlikowska, T., Riquelme, A., Sethi, A., Soemantri, D., Wearn, A., Wolvaardt, L., Yusoff, M. S., & Yau, S.-Y. (2022). Medical students’ and trainees’ country-by-gender profiles: Hofstede’s cultural dimensions across sixteen diverse countries. Frontiers in Medicine, 8, Article 746288. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.746288

Morgan, M. (2021). ‘Less grit, more quit’ has its benefits. BMJ, 373(8294). http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1376

Pelgrim, E., Hissink, E., Bus, L., van der Schaaf, M., Nieuwenhuis, L., van Tartwijk, J., & Kuijer-Siebelink, W. (2022). Professionals’ adaptive expertise and adaptive performance in educational and workplace settings: An overview of reviews. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 27, 1245–1263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-022-10190-y

Piaget, J. (1964). Part I: Cognitive development in children: Piaget development and learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 2, 176-186. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660020306

Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (2023, November 18). 2024 guide to surgical selection: 2025 intake. https://ww.surgeons.org/-/media/Project/RACS/surgeons-org/files/becoming-a-surgeon-trainees/Guide_to_Selection_2022_Final-Nov-2021.pdf

Sandars, J. (2009). The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE guide no. 44. Medical Teacher, 31(8), 685–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590903050374

Sandars, J., & Cleary, T. J. (2011). Self-regulation theory: Applications to medical education: AMEE guide no. 58. Medical Teacher, 33(11), 875–886. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2011.595434

Simpkin, A. L., & Armstrong, K. A. (2019). Communicating uncertainty: A narrative review and framework for future research. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 34(11), 2586–2591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04860-8

Simpkin, A. L., Khan, A., West, D. C., Garcia, B. M., Sectish, T. C., Spector, N. D., & Landrigan, C. P. (2018). Stress from uncertainty and resilience among depressed and burned out residents: A cross-sectional study. Academic Pediatrics, 18(6), 698–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2018.03.002

Singh, T. A. (2018). Self-regulated learning in professional students. The Clinical Teacher, 15(6), 513–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12965

Smith, T. M. (2020, October 5). Why the physician of the future is a master adaptive learner. American Medical Association. https://www.ama-assn.org/education/changemeded-initiative/why-physician-future-master-adaptive-learner

Southwick, S. M., Bonanno, G. A., Masten, A. S., Panter-Brick, C., & Yehuda, R. (2014). Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: Interdisciplinary perspectives. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), Article 25338. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338

Stephens, G. C., & Lazarus, M. D. (2024). Twelve tips for developing healthcare learners’ uncertainty tolerance. Medical Teacher. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2024.2307500

Stephens, G. C., Rees, C. E. & Lazarus, M. D. (2021). Exploring the impact of education on preclinical medical students’ tolerance of uncertainty: A qualitative longitudinal study. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 26(1), 53–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-020-09971-0

Stephens, G. C., Sarkar, M., & Lazarus, M. D. (2022a). Medical student experiences of uncertainty tolerance moderators: A longitudinal qualitative study. Frontiers in Medicine, 9, Article 864141. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.864141

Stephens, G. C., Sarkar, M., & Lazarus, M. D. (2022b). ‘A whole lot of uncertainty’: A qualitative study exploring clinical medical students’ experiences of uncertainty stimuli. Medical Education, 56(7): 736–746. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14743

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Wijnen-Meijer, M., Brandhuber, T., Schneider, A., & Berberat, P. O. (2022). Implementing Kolb’s experiential learning cycle by linking real experience, case-based discussion and simulation. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 9. https://doi.org/10.1177/23821205221091511

Williams, C. A., & Lewis, L. (2021). Mindsets in health professions education: A scoping review. Nurse Education Today, 100, Article 104863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104863

Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2020). What can be learned from growth mindset controversies? The American Psychologist, 75(9), 1269–1284. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000794

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. Pintrich, & Z. Moshe (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13–39). Academic Press.

Media Attributions

- Updated Concept Model of UT 4 © Kat Orgallo is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

Case-based learning activities which purposefully embed uncertainty through limiting or omitting information or by having the objective of the case focused on identifying next best steps or a differential diagnoses (as opposed to a definitive diagnosis). This type of uncertainty stimulus helps learners recognise that uncertainty is a natural part of healthcare practice. For more on this term, refer to Chapter 4.

Educational activities which challenge learners to apply knowledge learned in one context to another. Transferring learning can include applying previously learned textbook or theoretical knowledge to real-world cases or transferring skills and knowledge acquired in simulation to clinical practice. When transferring knowledge from one context to another, learners face uncertainty about which aspects of prior learned knowledge apply to the new contexts and also uncertainty about what new knowledge is needed in the novel scenario. For more on this term, refer to Chapter 4.