Chapter 1: Introduction to Outdoor Education Curriculum in Victoria

Josh Ambrosy and Sandy Allen-Craig

Learning Intentions

- Describe the structure of this book and identify its purpose

- Analyse reasons for including outdoor education in the school curriculum

- Define outdoor education and outdoor learning within your own contexts

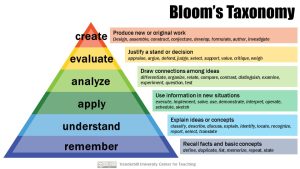

- Explain how Bloom’s taxonomy underpins the curriculum in Victoria

- Describe how this book can be used to develop your knowledge of teaching outdoor education

1.1 Why Teach Outdoor Education as Part of the School Curriculum?

Outdoor Education offers students a unique opportunity to learn about themselves and the world around them. It develops resilience, criticality and other personal competencies in young people that are key to surviving the complexities of our ever-changing world. Through outdoor education, students develop a greater understanding of the natural world and the impacts that changing human lifestyles are having on the planet. Via direct outdoor experiences, along with theoretical lessons, students question their own and a range of other peoples’ relationships with outdoor environments and how these relationships have changed over time.

Outdoor education, as a curriculum area, offers young people who partake in both experiences and the study of outdoor education more than simply the discipline-based knowledge that many would expect from other parts of the curriculum. It offers us, as teachers, an opportunity to engage with young people during some of their most significant developmental stages and equip them as resilient young people to manage the challenges they face now and into the future (Wattchow, 2023).

Victoria, Australia, has been at the forefront of outdoor education curriculum for over 40 years. Outdoor education in Victorian schools is both well-established and diverse in its take-up. Common articulations include the inclusion of specialist elective subjects and intensive experiences using a diverse range of outdoor environments. Despite the widespread uptake of outdoor education in Victoria and a significant body of research to support it, there is currently a lack of literature specific to teaching outdoor education curricula in Victoria to guide teachers in the development and deployment of their programs.

This book has been written to support initial teacher education students and teachers who want to develop their skills and knowledge to develop and implement outdoor education curricula in schools. Through writing this book, we aim to empower you as a teacher to build confidence in planning outdoor education programs that align with the Victorian Curriculum F-10 (VCF-10) and VCE Outdoor and Environmental Studies (VCE OES). This book has been written to respond to a gap in the literature, being a practical guidebook for teachers of outdoor education in Victoria. We hope that it is of value to you, and we wish you well in your future endeavours teaching outdoor education.

1.2 Curricula in Victoria

Curriculum in Australia is a complex and often politically driven tool that is used to dictate what happens in schools. Governments, parents, policymakers, academics, the broader community, and teachers all share a common interest in what is included in our curriculum and what is left out. As a teacher or future teacher, reading this book, you may have—or possibly through reading this book, you will have—developed your own views about what should and shouldn’t be included in the curriculum. Such thoughts are very worthwhile and should be part of your work as a teacher. This is because the curriculum is not, and should not, be treated as a stagnant or fixed apparatus. Rather, the curriculum is an ever-moving and continuously updated set of ideas that reflects society’s broader social and political movements. To enforce this point, we echo Yates et al. (2011) who offer that “Curriculum is a deceptively complicated topic” (p. 1). Through this book, we aim to help you feel more comfortable as a teacher working with the curriculum. In turn, we also hope it empowers you to understand that teachers can and should influence the curriculum in their classrooms, at schools and at a system level.

Australia is a federation of states. When you delve into the curriculum across the country, the impact of a federated system of government becomes prevalent. Historically, education, and in turn curriculum, was a state responsibility. A landmark decision in 2008 (Ministerial Council on Education, 2008) by all education ministers of the time led to the formation of ACARA (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority), and the development of a national curriculum—The Australian Curriculum. Despite the newly formed body, the responsibility for the implementation of the curriculum was left to each of the individual states. This has resulted in Victoria, like some other states of Australia, creating its own version of the curriculum and retaining a unique senior secondary curriculum.

In Victoria, there are two parts to the school curriculum: the Victorian Curriculum F-10 (VCF-10) and the Victorian Certificate of Education (VCE)[1]. The Victorian Curriculum F-10 is the state-based version of the Australian Curriculum F-10. It is an adaptation of ACARA’s curriculum that embodies state-based priorities. The VCE is Victoria’s senior secondary curriculum, through which students choose several subjects that are of interest to them. Through recent VCE reforms, students can also choose to study a vocationally focused VCE.

Outdoor Education is a significant part of many schools’ curriculum. Despite this, it is not formally included in all aspects of the curriculum in Victoria. Outdoor education is explicitly included in Victoria through the inclusion of VCE OES. VCE students can also elect to undertake vocational Outdoor Recreation certificates from the ‘Sport, Fitness and Recreation Training Package’. Despite this longstanding inclusion in the senior years’ curriculum (see 8.2), outdoor education does not have a formal recognition within the VCF-10 curriculum. Rather, teachers of outdoor education working in the F-10 year levels have two current options to develop curriculum for their classes[2]. The first is to use other learning areas, along with the general capabilities to develop integrated units of work, and the second is to deliver other areas of the curriculum through outdoor learning activities. In this book, we provide practical advice to help you develop a curriculum for your classes using both approaches, along with guidance on teaching VCE OES. This book does not focus on the teaching of vocational outdoor recreation certificates as the teaching of the content for those is heavily prescribed by the Sport, Fitness and Recreation Training Package.

1.3 Outdoor Education vs. Outdoor Learning

1.3.1 Outdoor Education

Outdoor education is a unique subject area. It has its own established curriculum, which in Victoria, is both formalised within the VCE and enacted (Marsh & Willis, 1999) within many schools at other year levels. Outdoor education differs from outdoor learning, which we return to at the bottom of this section. Although no single definition of outdoor education exists, it is important to preface this book with some common understandings of outdoor education. Outdoor education has been defined before as follows.

Outdoor Education focuses on personal development through the interaction with others and responsible use of the natural environment. It involves the acquisition of knowledge, values and skills that enhance safe access, understanding and aesthetic appreciation of the outdoors, often through adventure activities. (Victoria. Board of Studies (1995) Curriculum and Standards Framework (CSF). Melbourne: Board of Studies)

Through interaction with the natural world, outdoor education aims to develop an understanding of our relationship with the environment, others and ourselves. The ultimate goal of outdoor education is to contribute towards a sustainable community. (“Education Outdoors – Our Sense of Place.” 12th National OE Conference (2001) Bendigo, VIC)

Through interaction with the natural world Outdoor Education provides unique opportunities to develop relationships with the environment, others and ourselves. These relationships are essential for the well-being and future of individuals, society and our environment. (“The Human Face of Outdoor Education.” 11th National OE Conference (1999) Perth, WA.)

(S. Allen-Craig, personal communication, November 10, 2023. With permission)

1.3.2 Outdoor Learning

Outdoor learning is a pedagogical approach that can be used to deliver curriculum from other subjects. It is commonly used to teach curricula such as science, geography, health and physical education. Outdoor learning is not simply the process of taking students outside, rather, it is the delivery of curriculum through and with the outdoors as a site of learning. There are comprehensive resources to support the development of outdoor learning programs on the Outdoors Victoria website.

Learning Activity 1.1

Outdoor education and outdoor learning are terms that are often used interchangeably. We argue that this is not helpful and that a better understanding of each term is needed by teachers. Furthermore, outdoor education and outdoor learning, like many parts of education, are not fixed terms. Rather, their meanings are continually socially constructed by those who use them. Complete the following activity to help you better understand these terms.

- Define, in your own words, outdoor education and outdoor learning.

- Provide an example that you have observed in schools, or your own education, of each outdoor education and outdoor learning.

- Share your examples and definitions with a peer, and provide each other feedback on them.

- Revise steps 1 and 2 as needed following the feedback.

1.4 Bloom’s Taxonomy

Understanding Bloom’s Taxonomy as a teacher will help you to understand the underpinning structure of both state-level curricula and the curriculum you develop for your own classes.

Background Information

In 1956, Benjamin Bloom with collaborators Max Englehart, Edward Furst, Walter Hill, and David Krathwohl published a framework for categorising educational goals: Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Familiarly known as Bloom’s Taxonomy, this framework has been applied by generations of K-12 teachers and college instructors (or university lecturers) in their teaching.

The framework elaborated by Bloom and his collaborators consisted of six major categories: Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, and Evaluation. The categories after Knowledge were presented as “skills and abilities,” with the understanding that knowledge was the necessary precondition for putting these skills and abilities into practice.

While each category contained subcategories, all lying along a continuum from simple to complex and concrete to abstract, the taxonomy is popularly remembered according to the six main categories.

The Original Taxonomy (1956)

Here are the authors’ brief explanations of these main categories in from the appendix of Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Handbook One, pp. 201-207):

- Knowledge “involves the recall of specifics and universals, the recall of methods and processes, or the recall of a pattern, structure, or setting.”

- Comprehension “refers to a type of understanding or apprehension such that the individual knows what is being communicated and can make use of the material or idea being communicated without necessarily relating it to other material or seeing its fullest implications.”

- Application refers to the “use of abstractions in particular and concrete situations.”

- Analysis represents the “breakdown of a communication into its constituent elements or parts such that the relative hierarchy of ideas is made clear and/or the relations between ideas expressed are made explicit.”

- Synthesis involves the “putting together of elements and parts so as to form a whole.”

- Evaluation engenders “judgments about the value of material and methods for given purposes.”

The Revised Taxonomy (2001)

A group of cognitive psychologists, curriculum theorists and instructional researchers, and testing and assessment specialists published in 2001 a revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy with the title A Taxonomy for Teaching, Learning, and Assessment. This title draws attention away from the somewhat static notion of “educational objectives” (in Bloom’s original title) and points to a more dynamic conception of classification.

The authors of the revised taxonomy underscore this dynamism, using verbs and gerunds to label their categories and subcategories (rather than the nouns of the original taxonomy). These “action words” describe the cognitive processes by which thinkers encounter and work with knowledge:

Remember

- Recognizing

- Recalling

Understand

- Interpreting

- Exemplifying

- Classifying

- Summarizing

- Inferring

- Comparing

- Explaining

Apply

- Executing

- Implementing

Analyze

- Differentiating

- Organizing

- Attributing

Evaluate

- Checking

- Critiquing

Create

- Generating

- Planning

- Producing

In the revised taxonomy, knowledge is at the basis of these six cognitive processes, but its authors created a separate taxonomy of the types of knowledge used in cognition:

Factual Knowledge

- Knowledge of terminology

- Knowledge of specific details and elements

Conceptual Knowledge

- Knowledge of classifications and categories

- Knowledge of principles and generalizations

- Knowledge of theories, models, and structures

Procedural Knowledge

- Knowledge of subject-specific skills and algorithms

- Knowledge of subject-specific techniques and methods

- Knowledge of criteria for determining when to use appropriate procedures

Metacognitive Knowledge

- Strategic Knowledge

- Knowledge about cognitive tasks, including appropriate contextual and conditional knowledge

- Self-knowledge

Why Use Bloom’s Taxonomy?

The authors of the revised taxonomy suggest a multi-layered answer to this question, to which the author of this teaching guide has added some clarifying points:

- Objectives (learning goals) are important to establish in a pedagogical interchange so that teachers and students alike understand the purpose of that interchange.

- Organizing objectives helps to clarify objectives for themselves and for students.

- Having an organized set of objectives helps teachers to:

-

-

- “plan and deliver appropriate instruction”;

- “design valid assessment tasks and strategies”; and

- “ensure that instruction and assessment are aligned with the objectives.”

-

From Bloom’s Taxonomy [Teaching Guide], by Patricia Armstrong and Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. CC-BY-NC-4.0 .

1.4.1 Bloom’s Taxonomy and Outdoor Education Curriculum in Victoria

Bloom’s Taxonomy underpins the organising structure for both the Victorian Curriculum F-10 and the VCE. Both curriculum documents present a series of constructs and levels of application. The constructs tell us as teachers what is to be taught, whilst the level of application (of skill) articulates the cognitive level. Although named differently, in the F-10 vs. VCE curriculum, they function similarly. We discuss the specifics of the structures of the VCF-10 and the VCE in their respective parts of this book.

The taxonomy shown in section 1.4 demonstrates one understanding of a taxonomy of the application of knowledge from relatively low order thinking skills (name, identify) to more complex processes (evaluate, create, etc.). Whilst debate exists between scholars, teachers and policymakers alike around the use of a single taxonomy of application to underpin the curriculum in Victoria—the above is still a useful tool for teachers as they plan their outdoor curriculum as it prompts intentional planning beyond the question of ‘what is to be learnt?’ and furthers the planning process by encouraging us to think about ‘what level will this be learnt at?’ and ‘what level of achievement am I expecting from my students?’. As you undertake your planning for outdoor education curriculum, you should consider not only what is being taught but also the level of application that is desired.

1.5 Using this Book

This book has been written to assist both pre-service teachers and teachers of outdoor education to develop the skills and knowledge required to structure outdoor programs of study in Victoria. Pre-service teachers are emerging professionals, and hence, throughout this book, when we refer to the role of teacher, we collectively refer to both pre-service and qualified teachers. Each chapter begins with a series of learning outcomes to help frame the focus and learning of the chapter. As you work through the chapters, you should refer to and reflect on these outcomes. The learning outcomes are worded using Bloom’s terms in a similar way that they are articulated in both the VCE OES study design and the Victorian Curriculum F-10.

A series of learning activities for you to undertake are embedded within each chapter. These activities are designed to help you apply, in a practical manner, the skills and knowledge you are learning about. These activities range from analysing a case study to developing tools to use with your class. Each chapter concludes with a series of reflection questions. You might complete these in your own time or discuss them with others who are reading the book, such as your colleagues or university classmates. The book also contains a number of appendices through which we have provided examples, including unit planners and assessment tasks.

1.6 Overview of Book and Chapters

This book is divided into two parts, each with a distinct focus. Each contains a series of chapters offering practical advice about different aspects of the outdoor education curriculum in Victoria. The chapters are broken down as follows.

Chapters 2-7: Outdoor Education in the Middle Years. This section guides teachers in how to develop programs using the Victorian Curriculum F-10. This section explores how units of outdoor education can be developed using integrated curriculum structures drawing upon a range of learning areas in the Victorian Curriculum F-10 and the general capabilities. This section concludes with information about advocating for outdoor education in the middle years at both a school and a broader level.

Chapter 8-12: VCE Outdoor and Environmental Studies (VCE OES). This section unpacks the process for planning the curriculum for VCE OES. It has a significant focus on the development of assessment tasks for students and preparation strategies that can be used to help students prepare for both school-assessed coursework (SAC) tasks and examinations.

There are also a series of appendices that serve as examples of practice. Those numbered 1.1-3 relate to the Victorian Curriculum F-10, and those numbered 2.1-3, are related to chapters 8-12.

1.7 Glossary of Terms

The following terms are useful for outdoor education teachers. The terms defined here align with the VCAA’s use of these terms. They are useful for understanding the information in this book, the curriculum, and the associated curriculum support materials.

- Outdoor education: A field of study that teaches students about themselves, others and the environment through both study and experience of outdoor environments.

- Outdoor environments: refers to any outdoor places that students may visit or study as part of their curriculum. These vary from environments with minimal intervention by people to developed and urban areas.

- Outdoor experience: refers to a broad range of activities students undertake during outdoor education and outdoor learning programs. Activities during outdoor experiences vary from adventure activities to more passive pursuits.

- Outdoor learning: A pedagogical approach to teaching content and skills in other learning areas of the curriculum through outdoor experiences.

Chapter Summary

This chapter introduces the purpose and structure of the book, outlining how it supports both pre-service and in-service teachers in developing outdoor education programs aligned with the Victorian Curriculum F-10 and VCE Outdoor and Environmental Studies (VCE OES). It explores the significance of outdoor education, highlighting its role in fostering resilience, environmental awareness, and personal development. The chapter also provides an overview of curriculum structures in Victoria, discussing the complexities of curriculum development and the challenges outdoor education faces due to its lack of formal inclusion in the F-10 curriculum. Additionally, it distinguishes between outdoor education and outdoor learning, explaining their pedagogical differences, and introduces Bloom’s Taxonomy as a framework that underpins curriculum planning. Finally, it outlines how the book is structured, the key chapters, and how teachers can use it as a practical guide to enhance their professional practice.

Reflection Questions

- What can you expect to learn in this book?

- Why would you include outdoor education in the school curriculum?

- How does Bloom’s Taxonomy underpin the curriculum in Victoria?

- How can this book be used to develop your knowledge of teaching outdoor education?

References

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy [Teaching Guide]. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/

Marsh, C., & Willis, G. (1999). Curriculum: Alternative approaches to ongoing issues (2nd ed.). Merrill.

Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs. (2008). Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians. http://www.curriculum.edu.au/verve/_resources/National_Declaration_on_the_Educational_Goals_for_Young_Australians.pdf

Wattchow, B. (2023). ‘Through the unknown, remembered gate’: the Brian Nettleton lecture – Outdoors Victoria conference, 2022. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-023-00130-8

Yates, L., Collins, C., & O’Connor, K. (2011). Australian curriculum making. In L. Yates, C. Collins, & K. O’Connor (Eds.), Australia’s curriculum dilemmas: State cultures and the big issues (pp. 3-22). Melbourne University Publishing.

- Most schools in Victoria use the VCF-10 and the VCE; however, a small number of schools have chosen to implement the various components of the International Baccalaureate (IB) programs instead. ↵

- There have been longstanding calls for the inclusion of a formal outdoor education curriculum in Victoria. We discuss this further in chapter 6 ↵