Part 2 – Design

22 Supporting Students’ Self-Regulation through Online Learning Design

Kat Kenyon

In a Nutshell

We all make assumptions that our students are all digital natives and used to interacting with online spaces, but that is not always the case. Whilst many students are well-versed in social media and using the internet for fun, learning online requires a different skill set. Part and parcel of teaching online, is teaching students how to learn online. In this chapter, we offer ideas on how you can support your students’ self-regulation so that they can become better online learners.

Why Does it Matter?

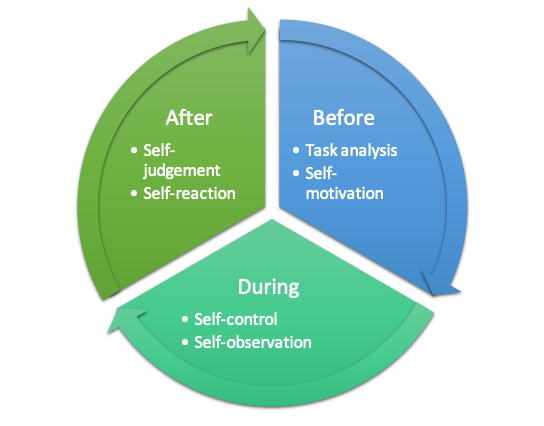

Self-regulation is the thinking, emotion, and behaviour that a learner uses to achieve their personal goals. It includes strategies such as planning, effort regulation, time management, metacognition, elaboration, critical thinking, help seeking, concentration and reflection (Burns, 2020). Different self-regulation strategies are used before (forethought), during (focus on performance) and after (reflection) each learning event (Zimmerman, 2002). By designing learning opportunities that support self-regulation in our students, we can equip them to become more successful both in their studies and as future professionals.

What does it look like in practice?

In this section:

- What is self-regulated learning?

- Course structure

- Learning Space

- Time Budget

- Checklists

What is self-regulated learning?

On-campus courses have a range of structures that help students to be motivated to self-regulate their learning. For example, there are fixed times for synchronous classes (e.g., lectures and tutorials), when students are expected to attend and actively engage with the content, the teaching team and their classmates. Peer associations are easier to build on campus, in and out of the classroom, where students can observe and discuss what others are doing in the course, indirectly helping them to stay on track with their learning.

When learning moves online, several of these structures for self-regulation are missing and this may be why students can flounder when studying online. If students can self-regulate when studying online or in blended environments, this improves their achievement and success (Broadbent 2017). Self-regulation is key to the development of lifelong learning skills, and it is therefore an extremely important skill to learn (Zimmerman, 2012).

The online learning environment needs to provide structures for students to self-regulate their learning, and provide the cognitive support to identify strategies for accomplishing learning tasks not attainable by the individual. This support or assistance is then gradually withdrawn as the learner becomes increasingly competent.

Self-regulated learning uses metacognitive, motivational and behavioural processes (Burns, 2020), and these processes are highly integrated.

- Metacognitive processes involve the student consciously thinking about and evaluating how they completed a task (the cognitive strategies used), and then adjusting these strategies as needed. Online synchronous sessions or forums are good ways for you to ask probing questions that will require students to explain their process for completing a learning activity (be it formative or summative).

- Motivational processes enable the student to set learning goals, ignore distractions, and positively learn from setbacks. This is where good feedback comes in. To learn more about this topic, see the dedicated chapter, Giving Good Feedback Online.

- Behavioural processes are typically positive behaviours associated with completing a task successfully. Some of these positive behaviours include reaching out to teaching staff for help, making a schedule for studying, and seeking additional help like a tutor for concepts or courses that they find difficult.

There are several learning design strategies and tools that can be used to help students develop a mental picture of what is required to be successful in a course and motivate themselves to engage with these within the appropriate timeframes. However, it can sometimes be a challenge for teachers to start thinking about student self-regulation as their headsets are focused on what they need to do as a teacher, rather than what students need to do as learners. Here are some suggestions on how to incorporate these strategies into your online learning design.

Course structure

A good course structure will support self-regulation before and during the learning process. Provide your students with a short video or plan to use your first synchronous online session to provide an overview of not just the course content, but how the course is run and where to find the basics on the course website (e.g., assessment information, how to get in touch with the teaching team, and how to navigate the course site itself). This will save you and them a lot of time.

Thinking about your students’ experience will also give you the opportunity to familiarise yourself with the course site from their perspective and ensure it is logical and easy to navigate. Ensure assessment instructions are clear, both in what is required of the student and how to submit the completed assessment.

A course with high levels of interaction that combines engaging content with opportunities for collaborative learning can help foster a sense of belonging and community, and increase the students’ motivation to learn (Burns, 2020). This means teaching staff should be visible and active on the course site. This might look like weekly check-ins via asynchronous (e.g., forums) or synchronous (e.g., Zoom) activities, or offering regular virtual office hours where students can contact you. Staff engagement will support students’ self-regulation behaviour during the learning process. For a more detailed discussion on educator presence, see the dedicated chapter, Building Online Communities with Your Students. Constructive feedback also helps build self-regulation after the learning process.

Learning Space

In face-to-face learning, students are usually in a lecture theatre, tutorial room, lab or clinic that has a specific purpose: to learn. Dedicated campus learning spaces carry sensory memories and give context to the activities the space is used for, thus mapping these spaces in students’ minds to traditional learning practices (Thomas, 2010). Studying online can be done from anywhere in the world, which opens a world of possibilities, but with it a world of distractions and requires more effort to develop learning practices and behaviours. Electronic devices, noise, pets, kids … these distractions can all make it harder for students to become self-regulated. Wardak, Vallis & Bryant (2021) used the hashtag #OurPlace2020 to encourage students to show their learning space during 2020 covid-19 lockdowns via video or photo, to maintain a sense of community amongst the students.

Encourage students early in the course to explore and then share their physical learning space (this will look different for everyone). It does not need to be the ‘perfect’ studying space! Students could share their intentional learning space in a forum and explain how it encourages their learning and minimises distraction or procrastination. It could be something as simple as leaving their phone in another room. This will help you understand the students’ learning spaces and where digital inequities may be occurring (Wardak, Vallis & Bryant, 2021).

This also applies to you as an educator – if you do some work away from campus, what does your teaching environment look like? What do you do to put yourself in the right frame of mind? Share this information with your students. By sharing your own space, you will help students feel connected to you and to their peers, and self-regulation is promoted before, during and after the learning process.

Time Budget

Another strategy to support online students’ self-regulation is the time budget. Time budgets are a visual map of all the student needs to do, week by week through the study period (Quinn and Wedding, 2012).

Time budgets are useful for students to self-regulate before they start studying to help plan what they need to do, but time budgets are also good during the learning process. For example, if students are finding that they are taking more time on an activity than what was allocated in the time budget, they should address their behavioural processes and seek help.

In an ideal world, students would use a tool such as a study planner (most student support units provide a template for students on their corporate website) to plan their time, but it is good to set clear and high expectations for students of what is involved in being successful learner in a course using tools such as the time budget, particularly in first year courses where students are still adjusting to university study. By creating a time budget, you can also see a visual representation of the course content and identify where content may be too heavy or too light. You can use a simple table with colour blocking to create your course Time Budget, like in this template.

Checklists

Checklists are one of the simplest strategies that can be implemented to support student self-regulation before, during and after the learning process. You can create a checklist in Microsoft Word or Excel that students can use to ensure they are meeting the learning objectives. A good example of an Excel-created checklist, which also includes time predictions, is available in Burns (2020; Figure 3).

Some Learning Management Systems (LMS) offer the possibility of creating a learning planner, which generates weekly checklists for students of what they need to know and need to do in the course. Each element on these lists can be additionally linked to the course learning outcomes that are being developed through a resource or an activity. It is useful to provide a Need to Know list, which comprises the learning objectives for the week/module/topic, and a Need to Do list, which reminds students of what activities they need to complete to meet the learning objectives.

At UniSA….

At UniSA….

UniSA Online utilises the Moodle learning planner tool to generate weekly checklists for students on what need to know and do. Each element on these lists is additionally linked to the course objective that is being developed. As the students complete each component, they can check it off and the system will remember their progress.

A self-regulation tool that is available in Moodle, is the time-management tool called the Completion progress block. This tool visually shows which activities the student needs to engage with and has a colour coding system showing where they are up to, so it supports self-regulation before, during and after the learning. As a bonus, there is also an Overview function for teachers that displays the progress of all students on one screen.

For examples of some of the strategies discussed in this chapter, take a look at the course tour for UO Critical Approaches to Online Learning (course structure) and a completed Time Budget.

Knowledge Check – What did you learn?

What does it all mean for me?

Consider how you can incorporate self-regulation strategies into your online course design. For example:

- Design a Course Overview Video:

- Create a 3-5 minute video that introduces your course. Include details about the course structure, how to navigate the course site, key contact information, and tips for succeeding in the course.

- Create a Time Budget Template:

- Develop a time budget for one of your courses. Outline the weekly tasks and estimated time requirements. Share this template with your students at the beginning of the course.

- Develop a Learning Space Activity:

- Ask your students to share a picture or description of their learning space in a discussion forum. Encourage them to explain how their chosen space supports their learning and minimises distractions.

- Implement a Weekly Checklist:

- Create a weekly checklist for your course, detailing what students need to know and do for each module or topic. Link each item to specific course objectives to provide clarity and direction.

Implement these changes and gather evaluation data (e.g. student feedback, assessment results, peer-evaluation) to check whether they are improving support of your students’ self-regulation.

References

Broadbent, J. (2017). Comparing online and blended learner’s self-regulated learning strategies and academic performance. The Internet and Higher Education, 33, 24–32.

Burns, M. (2020, March 19). Turning On, Tuning In, And Dropping Out. eLearning Industry, https://elearningindustry.com/self-regulation-in-online-learning

Quinn, D. & Wedding B. (2012). Responding to diversification: Preparing naïve learners for university study using Time Budgets, In M Brown, M Hartnett & T Stewart (eds), Future challenges, sustainable futures (pp. 743-747). Proceedings ASCILITE Wellington 2012, https://www.ascilite.org/conferences/Wellington12/2012/images/custom/quinn,_diana_-_responding_to.pdf

Thomas, H. (2010). Learning spaces, learning environments and the dis‘placement’ of learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(3), 502–511.

Wardak, D., Vallis, C., & Bryant, P. (2021). #OurPlace2020: Blurring Boundaries of Learning Spaces. Postdigital Science and Education, 4, 116-137.

Zimmerman, B.J. (2002). Becoming a Self-Regulated Learner: An Overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(2), 64-70.

Further Resources

Educator Alison Yang (2020) developed a visual guide for students to learn specific strategies to develop their motivation. The guide is under Creative Commons licence, so can be downloaded and shared on your course site with your students.

Media Attributions

- SLR

- Private: UniSA Logo