Collaboration

Values Based Approaches to Evidence for OER Advocacy

University of Southern Queensland

Emilia C. Bell; Nikki Andersen; and Dr Adrian Stagg

Overview

Data collection to support open education is often viewed as a stage of institutional maturity, and concentrates on evidence aligned with student success and equity (Colvard, Watson, & Park, 2018). Cost savings versus traditional commercial textbooks, number of student users, and downloads are all used by advocates to demonstrate the value of open education initiatives, usually in forms of advocacy (such as securing resources to continue programs). Increasingly, student achievement data is collected, linking the access and authenticity of open educational resources (OER) access and authenticity to improvement in academic performance (Tlili et al., 2023). However, in most cases, the platforms and infrastructure supporting data collection and presentation are determined without including those whose experience the data represents, or purportedly benefits.

At the University of Southern Queensland (UniSQ) Library, open educational practice (OEP) is built on a community of practitioners who contribute and feel empowered to share their practice. ‘Practitioner’ refers to “any staff member engaged with OEP (whether enacting OEP in teaching and learning directly with students, or providing direct support for OEP such as that provided by academic librarians, learning designers, and Copyright officers)” (Stagg, 2023, p. 3). This community-based approach aligns with the values-based approach that the Library’s Evidence Based Practice team takes to encourage agency in open narratives (Bell et al., 2023a). The UniSQ Library’s use of data and dashboards to demonstrate the value of OER and support ongoing evaluation empowers open textbook authors, giving agency to advocate for open education and share practices.

Dashboards and institutional reporting do not often provide space for relational approaches; however, UniSQ Library achieves this through intentional data practices that centers and elevates people. Such a relational approach situates the university in its community and helps to position open education advocacy in its greater social context, recognising relationships and interdependencies that are dynamic and impact how our practices evolve (Lacković & Olteanu, 2024). In taking a relational approach, shared community values are realised and highlight the ’why’ of being open and evidence-based (Bell et al., 2023b). Being both evidence- and values-based places evidence and values as complementary – they exist in partnership (Fulford, 2008; Stoyanov et al., 2020). Values-based practice emphasises that decision-making needs to consider “preferences, needs, hopes, [and] expectations” (Fulford, 2008, p. 10) alongside evidence.

Using this case study

This case study is beneficial for library staff, academics, and open education practitioners. Readers will:

- Develop their understanding of how evidence-based and values-based practice can support value and impact assessment and continuous improvement for open textbooks.

- Gain practical insight into the development of a data dashboard and the importance of community-building to situate data in its social context.

- Learn how questions can guide intentional data practices to elevate people and community needs in decision-making and reporting.

Key stakeholders

At UniSQ, the Library’s Open Educational Practice team has adopted the slogan ‘open is everyone’s business.’ This means they look for ways to build a community that encourages sharing. It is also an invitation for every team at UniSQ to consider what they can contribute to open education or the extent to which open education can help achieve existing goals or meet specific challenges that closed systems cannot. This has led to a long-standing relationship with the Library’s Evidence Based Practice team, prompting collaborations that support continuous improvement, value and impact, and decision-making for open education. This cross-team library collaboration and the shared values that underlie it support practitioner engagement with open practices.

Practitioner engagement with OEP is ‘complex, personal, contextual, and continually negotiated’ (Cronin, 2017, p. 28) and needs to be framed at the individual level. The lived experience, or ‘lifeworld,’ of each practitioner is mediated by complex, nuanced relationships between the individual, the institution, and society, creating an ecology of practice: a lens through which broader practice can be understood (Stagg, 2017). As such, the centrality of practitioner values is critical to an understanding of OEP, and to support communities of practitioners at the institutional level.

Background

Practitioners – and educational activities – are driven by values and a belief in ideals (whether expressed explicitly or implicitly) such as social responsibility, social justice, and empowerment (Warren, 2000). Constructing a culture in which open education is a viable and supported learning and teaching approach requires deliberate and purposeful community-building predicated on shared values and trust. In supporting OEP, trust builds social capital among participants and extends to all aspirations, interactions and outcomes of practice – both individually, and as a community (Stagg & Partridge, 2019). Coleman (1990, p. 4) asserts “a group whose members manifest trustworthiness and place extensive trust in one another will be able to accomplish much more than a comparable group lacking that trustworthiness and trust.” Therefore, supporting open practitioners is predicated on engaging with practitioner values and beliefs. The framework for this engagement at UniSQ is Fullan and Stiegelbauer’s Theory of Educational Change (1991). The framework situates change in practice as deeply personal and dependent on a supportive community for success, and expressly privileges agency and autonomy within the process. Predicated on positioning OEP as educational change, community formation recognises that change requires scaffolding, ownership by those enacting change, and sufficient time and (safe) space to experiment. Sustainable change of practice, ownership of the new, and a commitment to continual experimentation in learning and teaching is reliant on engaging deeply with practitioners – a process underscored by recognising the role of individual and professional values, aligning practice with values, and building a cadre of practitioners who explicitly explore and respect community values.

To realise the full benefits of community-building and partnership, OER requires a functional alignment and integration of OEP and evidence-based practices. Evidence-based library and information practice (or EBLIP) is a process that involves collecting, interpreting and applying evidence, including research, to support decision-making and continuous service improvement (Howlett & Thorpe, 2018). This extends to assessing or evaluating the value and impact of library services and resources. Evidence-based practice overlaps with the concept of ‘library assessment,’ and it is the term typically used in Australian libraries. This familiar concept can be applied to evidence-based OER advocacy.

A data dashboard

To tell these stories about the reach of OER or students’ access requires asking the right questions to collect the right evidence. Questions drive the evidence-based practice process and are the starting point to help us define the problem or decision to be addressed. At UniSQ, our questions resulted in a data dashboard that academic authors and library staff could access. In the lead-up to creating a data dashboard, initial discussions and reflection between the Library’s Open Educational Practice team and Evidence Based Practice took place to assess the ‘right’ evidence to be collected and its feasibility. Reflections were supported by an OPEN (Objective, Purpose, Evidence, and Narrative) approach that helped to articulate what needed to be known, collected, and communicated from evidence for library staff and academic authors (Bell et al. 2023a). The discussions were expanded to include consultation and drop-in session with academics which further helped to determine which specific metrics were important and why the data was relevant to practice.

This discussion process started by considering the overarching values around openness, helping to understand the wider social and cultural context driving our questions. From this, UniSQ Library teams drilled down to questions that could be answered with the data initially available, exploring how the data could inform decisions around creating and publishing the text itself. Authors were asked what data was important to them and why.

- Was it relevant to their research, learning, or teaching?

- Would it help with academic promotion?

- Was there any data already being collected that was not relevant or needed?

This enabled us to achieve a dashboard that situates evidence and data within its social context. Community partnerships and relationships informed what UniSQ Library did or did not choose to collect.

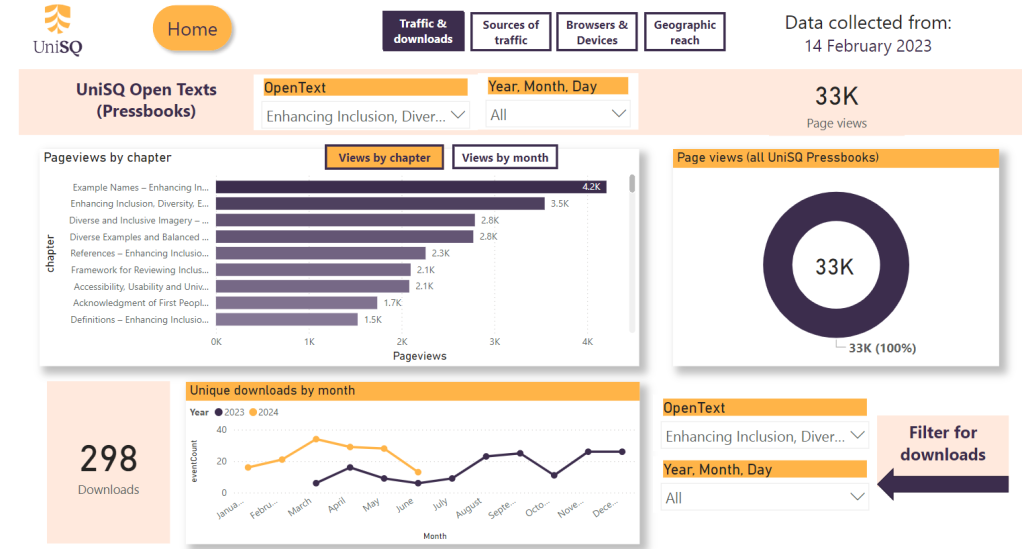

The Power BI report produced has a dedicated page for each of UniSQ’s open texts and can be accessed by individual authors. The data dashboard predominantly uses web analytics data to demonstrate the attention and reach of open texts as an initial proxy for impact. It is designed for our open textbook authors to track the use and reach of their work and highlight how it contributes to the overall success of open education at UniSQ. The main feature of the data dashboard is access. Authors have immediate access to the data. Community input was vital to ensuring a good understanding of what evidence the library and authors needed, but also understanding the purpose behind this data in relation to OEP values and the community that uses the dashboard.

Key outcomes

The dashboard has highlighted the attention open texts receive and has been a new way to promote OER output. The dashboard is split into four tabs for authors to navigate:

The process of EBP can help to facilitate critical reflection on practice, driving its continuous improvement and the potential to change. Where reflective practice provides a link between theory and practice, EBP can support the application of knowledge gained from reflection into decision-making. This may include decisions on accessibility, the form of openness, platforms used, or how practice fosters values of openness and facilitates learning.

One of our most popular open texts, Fundamentals of Anatomy and Physiology is read by a diverse cohort, with many UniSQ students unable to access the online version due to connectivity issues in rural and remote regions. Hence, it was important to use an evidence-based approach to discover students’ reading strategies and educational reality. UniSQ found that PDF versions of the text and reading on mobile phones were popular for these students. Here, the data dashboard helps to facilitate an evidence-based approach to understanding these educational realities and what access might look like for students in their local context. As a direct result, the team sought to ensure Pressbooks tools for readability were adopted (e.g., that all tables used the TablePress plugin in lieu of HTML coding, thus improving the mobile device experience) and responded to feedback asking for more H5P activities to support self-assessment and revision. The PDF versions contained links to online content, allowing students to revise core content, and use their internet connection time more strategically to focus on specific learning content. Additionally, this evidence has provided a foundation for discussions with other authors to encourage the extension of practice into more interactivity, enhancing the learning design of their content.

Not only is evidence being used for decision-making and continuous improvement, but also for advocacy of the value of OER. By starting with questions, UniSQ is intentional in choosing what to collect and supported acknowledging the values and social justice orientation of open education. When thinking about the value of OERs (e.g., economic, social, equitable), it meant also thinking about values (e.g., social justice, accessibility). The Library needed to incorporate the trust that was built into open education communities into the choices made when collecting, analysing, or sharing evidence. It was important to go beyond focusing on the processes and structure of evidence-based practice and instead to understand the relational aspects of it that can elevate people. Since its inception in September 2021, the open textbook data dashboard has been positively received by all authors, and the data has supported research (conference papers and journal articles), teaching and learning practice (identifying key areas for continuous improvement or evaluation of changed practice), and professional endeavours (the data has been included in performance reviews, applications for external funding, and promotions documentation).

Learnings and recommendations

A challenge in using web analytics data is its ease of access. It can be easily measured and appear overly promising, creating appeal for its use. This reinforces the importance of collecting meaningful and accurate data and ensuring transparency in communicating data limitations and its use. It is where asking the right questions matters (Drabinski & Walter, 2016) and where evidence-based practice extends into open practices. Asking questions helps us to recognise the broader context, motivations, and needs that drive why UniSQ Library was collecting evidence in the first place. Questions can ensure evidence aligns with the contributions that OER make to social justice and promote ongoing reflection into why and how UniSQ engages in open practice.

In being intentional and purposeful in what UniSQ chooses to collect, critical reflection on whose voices, values, and perspectives are contributing to our evidence is key. A person-centred approach is taken that relates evidence back to individuals. The evidence collected is recognised as existing in partnership with underlying values and a wider social context and can contribute positively to the communities that open education partners with. There is potential to see evidence-based practice (or library assessment) as a relational process. Douglas (2020, p. 47) describes “assessment as care,” a concept that prioritises connection and people over reporting and products. It can, however, be uncomfortable work, as it complicates the process of data collection and visualisation that makes up dashboards, as such outputs do not usually create space for concepts like care or connection (2020, p. 6). Community partnerships and user experience, which require greater time and connection, are easily neglected as evidence as their human nuance and complexity cannot seamlessly be displayed in a quantitative data dashboard.

In practice

The authors offer the following advice for others wanting to create a dashboard to track open textbook analytics:

- Prioritise people and connection over analytics and reporting – engage open textbook authors in developing a dashboard and give them agency over their data.

- Be intentional and purposeful in the data you collect – start by asking the right questions to collect the right evidence.

- Be transparent about data limitations and their use. UniSQ Library approached this by providing examples of appropriate data use-cases, adding disclaimers to the dashboard for data limitations, and providing drop-in sessions that invited data literacy questions and education.

References

Bell, E. C., Andersen, N., & Stagg, A. (2023a). Access and agency: Evidence and values-based approaches to OER value and impact [Conference presentation]. North East Regional OER Summit. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14394/37217

Bell, E. C., Andersen, N., & Stagg, A. (2023b). Evidence and values-based approaches in OER. ALIA LARK. https://web.archive.org/web/20240412204236/https://lark.alia.org.au/evidence-values-based-oer/

Colvard, N. B., Watson, C. E., & Park, H. (2018). The impact of open educational resources on various student success metrics. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 30(2), 262-276, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1184998

Douglas, V. A. (2020). Moving from critical assessment to assessment as care. Communications in Information Literacy, 14 (1), 46-65. https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2020.14.1.4

Drabinski, E., & Walter, S. (2016). Asking questions that matter. College & Research Libraries, 77(3), 264-268. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.77.3.264

Lacković, N., & Olteanu, A. (2023). Relational and multimodal higher education: Digital, social and environmental perspectives. Taylor & Francis.

Howlett, A., & Thorpe, C. (2018). “It’s what we do here”: Embedding evidence-based practice at USQ Library [Conference presentation]. Asia-Pacific Library and Information Conference (APLIC), Deakin, ACT.

Stagg, A., & Partridge, H. (2019). Facilitating open access to information: A community approach to open education and open textbooks. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 56(1), 477-480. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.76

Stagg, A. (2023). The ecology of open educational practices in Australian higher education: a practitioner-focused mixed methods study. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Tasmania]. https://doi.org/10.25959/26010949.v1

Tlili, A., Garzón, J., Salha, S., Huang, R., Xu, L., Burgos, D. & Wiley, D. (2023). Are open educational resources (OER) and practices (OEP) effective in improving learning achievement? A meta-analysis and research synthesis. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00424-3

Image descriptions

Figure 1: Screenshot of statistical dashboard

Statistical dashboard for the open text “Enhancing Inclusion, Diversity, Equity and Accessibility in Open Educational Resources” which shows the number of page reviews (33k), downloads (298) and most popular chapters. The top of the dashboard has four tabs: traffic and downloads, sources of traffic, browsers and devices, and geographic reach.

Acknowledgement of peer reviewers

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following people who kindly lent their time and expertise to provide peer review of this chapter:

- Ash Barber, Academic Librarian, University of South Australia

How to cite and attribute this chapter

How to cite this chapter (referencing)

Bell, E., Andersen, N. & Stagg, A. (2024). Values based approaches to evidence for OER Advocacy. In Open Education Down UndOER: Australasian Case Studies. Council of Australian University Librarians. https://oercollective.caul.edu.au/openedaustralasia/chapter/values-approaches-to-advocacy/

How to attribute this chapter (reusing or adapting)

If you plan on reproducing (copying) this chapter without changes, please use the following attribution statement:

Values based approaches to evidence for OER Advocacy by Emilia Bell, Nikki Andersen and Adrian Stagg is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

If you plan on adapting this chapter, please use the following attribution statement:

*Title of your adaptation* is adapted from Values based approaches to evidence for OER Advocacy by Emilia Bell, Nikki Andersen and Adrian Stagg, used under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.