Collaboration

Reimagining Open Textbooks Through a Decolonising Lens: Non-Linear Practices for Holistically Integrating First Nations Knowledges into Curriculum

La Trobe University

Dr Shirley Godwin; Dr Andrew Buldt; Steven Chang; Sebastian Kainey; Wendy Ratcliffe; Vivian Luker; Melissa Digiacomo; and Emerson Taylor

We acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the unceded sovereign lands on which this work was done, the Wurundjeri, Dja Dja Wurrung and Wergaia peoples, and pay respects to Elders past and present of all First Nations Communities. We acknowledge First Nations peoples as the original creators and teachers of knowledge in this country.

We recognise there is not one preferred term to represent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia nor can one term reflect the immense diversity of cultural ways of being across all Nations. We respect the right of all peoples to self-determine their identity. First Nations is the predominant term used in this work to represent sovereignty and diversity.

Using this case study

This case study will be useful to several cohorts of readers.

Overview

This case study describes our project to transform an undergraduate open textbook at La Trobe University. At the time of writing this case study the revised version of the text is forthcoming. Here we share one of our key outcomes: the collaborative process we are using to make the transformative revisions.

We reflect on a First Nations-led cultural safety review process that is enabling health science academics and library staff to jointly reconstitute this Open Education Resource (OER) as a culturally responsive text that is inclusive and accessible for diverse learners. We highlight the role of First Nations staff in leading a decolonising agenda and how non-Indigenous practitioners are supporting them through culturally responsive practices.

We focus on how the project embodies First Nations ways of knowing, being, and doing through Third Spaces that foster power equity and mutually beneficial two-way learning. These ways of working provide an active alternative to the emotionally based paralysis that commonly affects non-Indigenous people, stemming from a fear of “doing the wrong thing”. This often demobilises their capacity to transform beyond allyship on an individual level (which can be tokenistic or performative and a way to stay comfortable) into ‘accomplices’ striving for wider systemic change, regardless of personal or professional discomfort (Finlay, 2020; Rix et al., 2023).

Our approach is part of a broader paradigm shift to integrate First Nations knowledges into higher education curriculum in a meaningful way that is holistic rather than tokenistically additive. This paradigm shift reflects a decolonising approach which requires de-centreing dominant Western perspectives by challenging deeply rooted conventional norms and principles, and re-positioning colonial power in collaborative relationships (Smith, et al., 2018).

We conclude our case study with some final reflections as prompts for practitioners to use for normalising culturally responsive practices in the Australian open education movement. We invite open education practitioners to join us on this shared journey.

Beginnings and new ways of thinking

Our project started as an initiative to update an open textbook but took us on a greater journey of growth where we created new ways of thinking and working. Enhancing our team’s capacity to work in culturally responsive ways took time and cultivation by overcoming knowledge gaps that our non-Indigenous project members had. We recognise this is an ongoing learning process.

First Nations knowledges not on the radar

The idea of integrating First Nations knowledges was quite peripheral to our initial plan. Our priority had been to create a new edition of the OER Research and Evidence in Practice, the prescribed text for a core research methods subject across undergraduate health disciplines. The 1st edition was published in 2018 and needed major updates to stay current, including enhanced interactivity and accessibility. We assembled an initial team of one health sciences academic and two open education staff from the La Trobe eBureau (all non-Indigenous).

Since the publication of the original edition, First Nations content has been included in the health science subject, and as part of that, an appraisal of the OER textbook was also arranged. The insights of a First Nations academic led us to recognise that the 1st edition of the text was not culturally responsive in its perspective and content. This in itself was an important lesson; OERs enable powerful potential for social justice (Lambert, 2018), but it does not follow that all OERs are therefore automatically culturally safe (Nusbaum, 2020). It quickly became clear that a cultural safety review was needed.

Understanding cultural safety

We increasingly drew on the perspective of the First Nations team member, which was decisive for identifying a greater range of limitations than we had first understood. We first focused on minimising limitations, but we soon reached a tipping point where we recognised the need to solve more fundamental problems. As a result, this collaboration has become increasingly reflexive as we reassessed our purpose.

A key lesson was to understand the distinction between culturally responsive practices and creating actual cultural safety. We learnt that the rapid proliferation and differing interpretations of terminology in this space means deliberate clarity is essential for authentic practice. Based on First Nations-led understandings and appreciating that there are shared features, here is how we understand this pair of concepts:

This distinction enabled us to be clearer about the expanded purpose of our project. It also meant we grasped how we would judge whether our work achieves our goals. For example, recognising the definition of cultural safety meant we used the term more judiciously. As part of this, we understand that the primary criteria for determining whether our open textbook is culturally safe or not for First Nations educators and learners can only be judged by First Nations peoples.

Tangible resourcing for First Nations engagement

During the initial planning stage, we had advanced our awareness, but our non-Indigenous project members had no lived experience of a cultural safety review. We recognised the need for such reviews and saw it as a high priority because of both informal and institutional leadership in our work environments (within the University and the OER community) about embedding First Nations knowledges. Despite our enthusiasm, our inexperience and biases led to our naïve assumption that including a cultural safety review in the project would be as simple as inviting a First Nations expert to provide one as a separate process to the main work.

Through reflective shared practice, we soon recognised that the work involved in undertaking a cultural safety review is demanding and time-consuming. First Nations people make up a small proportion of university staff, and these practitioners are often overburdened with requests like these in addition to their regular duties. Tangible support is therefore a key enabler of cultural safety projects to mitigate the risks of burnout for First Nations staff. Ideally, this support provides direct funding for the labour, expertise, and experience required.

In July 2023 the University Library was pursuing diverse avenues to sustainably fund open education projects at the La Trobe eBureau. We successfully identified a funding opportunity through collaboration with the Alumni and Advancement Office. These funds were donated by the family of an international student who tragically passed away during his studies at the University. The family’s wish was to fund a project with lasting impact for as many learners as possible (as opposed to a short-term single scholarship).

Several candidate open education projects needed funding, but our proposal was successful because of the advocacy by non-Indigenous professional staff in communicating the project’s alignment with both the donor family’s wishes and Library management priorities. This advocacy was driven by our fresh recognition of how important it is to tangibly support First Nations contributions, rather than just rely on goodwill and passion.

Moving forward with new ways of working

Successfully funding the project was a major outcome that laid the foundation for committing to sustained ways of working together cross-culturally and across the traditional academic and professional divide.

The Third Space: Lateral collaboration across conventional boundaries

We organically created collaborative practices that resemble the ‘Third Space’. Features of this Third Space include lateral collaboration across departments to bring together different expertise and experiences, non-conventional project roles and shared responsibilities, and co-leadership with joint navigation of paradoxes and dilemmas (Whitchurch, 2012, 2015). The non-hierarchical nature of our work within this Third Space enables a two-way, critically reflective process of knowledge sharing and decision making.

Figure 1: The Third Space as a shared space of mutual learning: we deliberately avoided using a Venn diagram to emphasise our equal positioning within this shared space. Click the plus signs for details of the cross-departmental project team and for examples of how our practices aligned with the features of a Third Space.

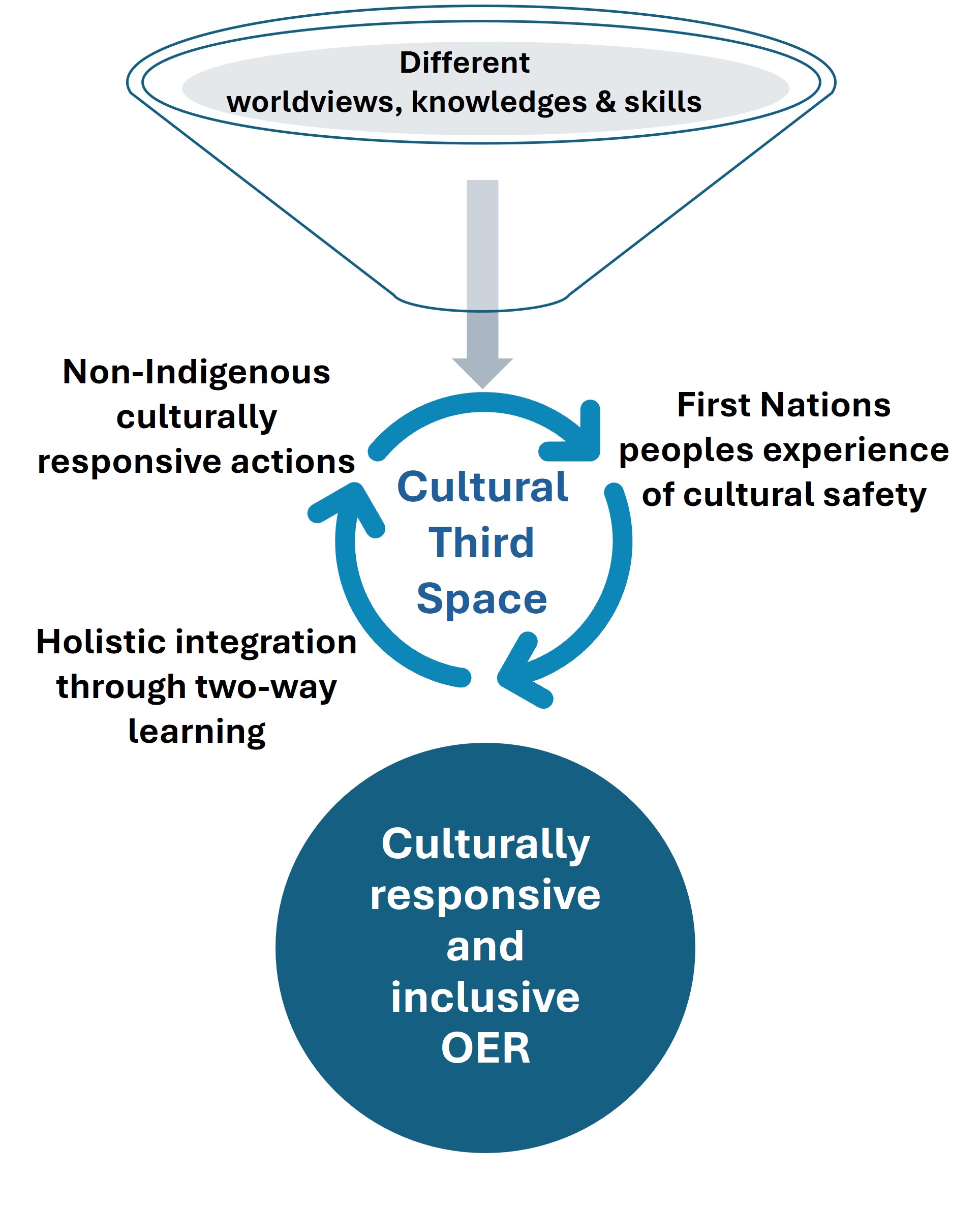

The Cultural Third Space (a cultural interpretation of the academic-professional Third Space nexus) is another helpful way of explaining how we work. It is a cultural interface where respectful co-leadership can create overlapping spaces to join up synergies between both First Nations and Western knowledges (Nakata, 2002; Dudgeon & Fielder, 2006).

For example, in reimagining our revised OER, we do not discard the teaching of Western scientific methods simply because it is Western in origin. Instead, we use First Nations perspectives to critically expose the ways these conventional methods exclude First Nations ways of creating knowledge, including storytelling, as research tools and First Nations worldviews and lived realities,s which provide important context for quantitative statistics, and how this all adds up to cause significant harm in health sciences research and practice. Combining the benefits of Western scientific methods with knowledge creation based on millennia of First Nations ways of knowing, being and doing supports a decolonising approach that facilitates epistemic equity and justice (Dudgeon & Gray, 2023). Working within this space also shifts the sole responsibility for explaining and justifying the inclusion of First Nations perspectives from First Nations peoples to shared positioning across the team.

Figure 2: The Cultural Third Space, an intersection where First Nations and Western knowledges are equally valued and merge to co-create new understandings. Click on the plus sign to see key features of the Cultural Third Space created for this project.

Inclusion of First Nations knowledges

Our approach to creating an authentic Cultural Third Space was powerful for planning how to integrate First Nations knowledges into the adapted OER. A “butcher’s paper” approach of ideating, reflecting, and reconfiguring different schemas helped us to transition from an additive approach to a holistic approach.

Limitations of the default “additive” approach

We initially set out to include First Nations knowledges through a cultural safety review of the book and adding a new separate section or chapters to what existed. What we call the “additive” approach here is a common method used by default, where First Nations perspectives are added to fill a gap with minimal changes to existing core content.

The leadership of our First Nations project member enabled us to recognise that simplistically adding content in this way tends to generate problematic outcomes.

Figure 3: A simplistic additive approach to including First Nations knowledges in the revised OER. Click on the plus sign to see the problematic outcomes of this approach.

Solution – an integrated holistic approach

We consciously decided not to treat First Nations knowledges as separate from the OER’s main content, so we are developing a holistic approach that involves:

- Distinguishing between Indigenisation (adding First Nations content as optionally relevant) and Decolonisation (integrating First Nations content as equally valid)

- Interweaving First Nations knowledges within our explanations, examples, and objectives in every chapter

- A paradigm shift in ways of thinking and working

- Self-determined input from First Nations academic with shared responsibility and ownership of outcomes across the team

Some examples of culturally responsive holistic integration include:

Figure 5: Outcomes of holistic integration of First Nations knowledges and worldviews. Click on the plus signs for details of outcomes in each category.

This integrative approach makes the final product everyone’s responsibility and leads to more authentic inclusivity. The paradigm shift in ways of thinking and working can provide a leading example of how to integrate First Nations knowledges into the higher education curriculum more broadly. It is valuable as a respectful approach that is culturally responsive and holistic rather than tokenistic.

Recognising process as an output

A theme that arose many times is the value of process, not solely as a means to an end, but as a powerful way of transforming our fundamental ways of thinking and working. When expressed clearly and aligned with certain purposes, these ways of working are outputs in their own right that can model effective collaboration for others. This is especially useful in the open education movement, as projects driven by open educational practices (OEP) naturally encourage open ways of working. By sharing these practices as openly licensed artefacts (e.g. this case study), we can extend the “five Rs” of OER to cover not just content but also practices for benefiting the whole OEP community.

We have developed and continue to refine strong collaborative processes in carving out spaces for generating culturally responsive ways of working together that cultivate mutually beneficial two-way learning. Through critical engagement with the process, our understanding of the project has changed in an organic way, and the final product will be better as a result.

Non-linear “process as pedagogy”

A powerful aspect we want to highlight is the non-linear nature of how we arrived at where we are. We often found ourselves diverging from “the meeting agenda” into conversations that would conventionally be labelled “tangents”. Normally, this might seem like a waste of precious time. On the contrary, it turned out to be the key to reaching our most important lessons and decisions like choosing a holistic way to integrate First Nations knowledges into the OER.

If this involves significant mutual learning, a way to frame this might be “process as pedagogy”.

Figure 6: Non-linear ideation. Sometimes in order go forwards, you need to go backwards or follow unplanned tangents first. Click on the plus signs for details of practical enablers and outcomes of non-linear ways of working.

Barriers and Enablers

Through critically reflexive practice, we were able to identify barriers and enablers for transformative ways of thinking and working to achieve our intended outcomes. These are represented in Figures 7 and 8.

Figure 7: Barriers to culturally responsive practice and the potential outcomes. Click on the plus signs to see more details.

Figure 8: Enablers of culturally responsive practice for creating Cultural Third Spaces and the potential outcomes. Click on the plus signs to see more details. See Figure 2 for features of the Cultural Third Space.

Navigating open licensing

We encountered and resolved a series of complex open licensing challenges during our journey. Major OER adaptation projects are relatively new to Australian learning & teaching practices. So here we outline these barriers and how we resolved them as our contribution to suggesting norms around these practices.

The first challenge we needed to resolve was the restrictive ND (No Derivatives) license that applied to the original edition of the OER we set out to revise.

Secondly we needed to reflect on norms for transformative adaptations of open content and consider how best to respect the integrity of the original authors’ work while not limiting the changes we feel are necessary.

A third challenge we encountered was navigating the importance of protecting the sovereignty and integrity of First Nations intellectual property in open licensing contexts which allow for not only access to information but also the freedom to reuse, potentially inappropriately.

Final Reflections

Reflecting on our involvement in the project, we’ve identified key principles that can guide open education practitioners in fostering culturally responsive practices, especially in decolonising knowledge. These principles emphasise the need for intentionality, incorporating diverse perspectives, collaborating with First Nations peoples, and actively challenging existing power structures in education. By adopting these approaches, practitioners can create a more equitable and culturally rich educational environment, ensuring that open educational resources (OERs) not only share knowledge but also respect and reflect diverse ways of knowing.

Our experience highlights key lessons that can be adapted by the Australasian OEP community:

OERs do not inherently promote social justice. While they have the potential to increase access to knowledge and enable culturally responsive adaptations of content, achieving true equity depends on the open practitioner’s agency to support thoughtful planning, intentional effort, and advocate for funding diverse expertise. Practitioners must go beyond merely creating or sharing resources; they need to address imbalances in representation, accessibility, and cultural relevance to make a meaningful impact on systemic inequalities.

Gently navigating complexity is critical when generating new knowledge or driving cultural change. It’s not just about working with different methods side by side but embracing the challenges and nuances that arise in creating something new. This complexity demands flexibility, patience, and openness to different perspectives, often leading to more innovative and transformative thinking. Practical steps can support these approaches, such as proactively creating agenda time to accommodate non-linear thinking and scheduling dedicated debrief workshops to mark project milestones. For example, we used this reflective debrief template designed for open education projects, and this getting-started guide can help with early ideation.

Effective project planning involves more than just adhering to deadlines. It requires prioritising relationship-building, fostering safe connections, and allowing space for tangents that lead to deeper insights. Balancing timelines with an organic, flexible process is essential for genuine collaboration. Regular meetings and clear communication ensured the team stayed aligned, allowing us to adapt goals and evolve as the project progressed.

Lastly, while non-Indigenous individuals can engage in meaningful work independently, authentic decolonisation and true progress occurs when the work is done in collaboration and shared leadership with First Nations partners. Working together, with co-leadership, fosters respect, shared knowledge, and a culturally informed process. This collaborative approach enhances the quality of the work and has the potential to drive sustainable, transformative change at both the individual and institutional levels, benefiting educational communities as a whole.

Conclusion

We set out to achieve a standard, strict-to-timeline, efficient output of an updated undergraduate open textbook. Our cultural safety review of the 1st edition acted as a catalyst to create a whole new range of practices and artefacts. We needed to re-examine what we were trying to achieve and critically reflect on how to produce something that is truly culturally responsive, inclusive, engaging and accessible. We didn’t take the easy route or step back from challenging conversations.

Both the text and our processes engage with First Nations ways of knowing, being and doing and are a step towards normalising holistic and integrated approaches to incorporating First Nations knowledges in education resources. Our case study demonstrates how respectful, reciprocal collaborative partnerships between First Nations and non-Indigenous team members can provide a decolonising lens to challenge entrenched conventional ways of working and reimagine OERs as culturally safe resources designed for universal accessibility.

In creating and working within an authentic Cultural Third Space, we have identified future directions for expanding culturally responsive practices in the growing Australian OER movement and invite open practitioners to use the story of our journey as a catalyst for wider change.

In practice

By adopting these approaches, practitioners can create a more equitable and culturally rich educational environment, ensuring that open educational resources (OERs) not only share knowledge but also respect and reflect diverse ways of knowing.

The following key lessons can be adapted by the Australasian OEP community:

- OERs do not inherently promote social justice

- Gently navigating complexity is critical when generating new knowledge or driving cultural change

- Effective project planning involves more than just adhering to deadlines

- While non-Indigenous individuals can engage in meaningful work independently, authentic decolonisation and true progress occurs when the work is done in collaboration and shared leadership with First Nations partners. Working together, with co-leadership, fosters respect, shared knowledge, and a culturally informed process.

Image descriptions

Figure 4: Holistic approach to integrating First Nations knowledges and worldviews

Image represents bringing together different worldviews, knowledges and skills creates a Cultural Third Space encompassing culturally responsive actions by non-Indigenous peoples, holistic integration through two-way learning and culturally safe experiences for First Nations peoples. The outcome from working in the Cultural Third space is a culturally responsive and inclusive OER.

References

Dudgeon, P., & Fielder, J. (2006). Third spaces within tertiary places: Indigenous Australian studies. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 16(5), 396–409. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.883

Dudgeon, P., & Bray, A. (2023). The Indigenous Turn: Epistemic Justice, Indigenous Knowledge Systems, and Social and Emotional Well-Being. In: J. Ravulo, K. Olcoń, T. Dune, A. Workman, & P. Liamputtong (Eds.), Handbook of Critical Whiteness. (pp. 1-19) Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-1612-0_31-1

Finlay, S. M. (2020). Where do you fit? Tokenistic, ally—or accomplice?. Croakey Health Media. https://croakey.org/where-do-you-fittokenistic-ally-or-accomplice/

Indigenous Allied Health Australia (2019). Cultural Responsiveness in Action: An IAHA Framework. https://iaha.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/IAHA_Cultural-Responsiveness_2019_FINAL_V5.pdf

Janke, T. (2021). True Tracks: Respecting Indigenous knowledge and culture. UNSW Press, Sydney

Lambert, S. R. (2018). Changing our (Dis)Course: A Distinctive Social Justice Aligned Definition of Open Education. Journal of Learning for Development, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.56059/jl4d.v5i3.290

Mohamed, J., Stacey, K., Chamberlain, C., & Priest, N. (2024). Cultural safety in Australia. Lowitja Institute, https://www.lowitja.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/CulturalSafetyinAustralia_DiscussionPaper_August2024.pdf

Nakata, M. (2002). Indigenous Knowledge and the Cultural Interface: Underlying issues at the intersection of knowledge and information systems. IFLA Journal, 28(5–6), 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/034003520202800513

Nusbaum, A. T. (2020). Who gets to wield academic Mjolnir? On worthiness, knowledge curation, and using the power of the people to diversify OER. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2020(1). https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.559

Ramsden, I. (2002). Cultural safety and nursing education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu [Doctoral dissertation]. Victoria University of Wellington.

Rix, E., Doran, F., Wrigley, B., & Rotumah, D. (2024). Decolonisation for health: A lifelong process of unlearning for Australian white nurse educators. Nursing Inquiry, 31(2), Article e12616. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/nin.12616

Smith, L. T., Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (Eds.). (2018). Indigenous and decolonizing studies in education: Mapping the long view. Taylor & Francis Group.

Whitchurch, C. (2012). Reconstructing Identities in Higher Education: The rise of “Third Space” professionals. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203098301

Whitchurch, C. (2015). The rise of Third Space Professionals: Paradoxes and dilemmas. In U. Teichler & W. K. Cummings (Eds.), Forming, recruiting and managing the Academic Profession (pp. 79–99). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16080-1_5

Acknowledgement of peer reviewers

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following people who kindly lent their time and expertise to provide peer review of this chapter:

- Mais Fatayer, Manager, Learning Experience Design, University of Technology Sydney

How to cite and attribute this chapter

How to cite this chapter (referencing)

Godwin, S., Buldt, A., Chang, S., Kainey, S., Ratcliffe, W., Luker, V., Digiacomo, M. & Taylor, E. (2024). Reimagining open textbooks through a decolonising lens: Non-linear practices for holistically integrating First Nations knowledges into curriculum. In Open Education Down UndOER: Australasian Case Studies. Council of Australian University Librarians. https://oercollective.caul.edu.au/openedaustralasia/chapter/reimagining-open-textbooks-through-a-decolonising-lens.

How to attribute this chapter (reusing or adapting)

If you plan on reproducing (copying) this chapter without changes, please use the following attribution statement:

Reimagining open textbooks through a decolonising lens: Non-linear practices for holistically integrating First Nations knowledges into curriculum by Dr Shirley Godwin, Dr Andrew Buldt, Steven Chang, Sebastian Kainey, Wendy Ratcliffe, Vivian Luker, Melissa Digiacomo, and Emerson Taylor is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

If you plan on adapting this chapter, please use the following attribution statement:

*Title of your adaptation* is adapted from Reimagining open textbooks through a decolonising lens: Non-linear practices for holistically integrating First Nations knowledges into curriculum by Dr Shirley Godwin, Dr Andrew Buldt, Steven Chang, Sebastian Kainey, Wendy Ratcliffe, Vivian Luker, Melissa Digiacomo, and Emerson Taylor, used under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

Cultural safety for First Nations peoples requires an analysis of power relations to create an environment where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples report that:

• their experiences are believed and validated

• their cultures are centred and valued in policy development, research, evaluation

and service design and delivery

• they feel welcomed and respected in policy, research, evaluation and service

environments

• they see other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people working in the policy,

research, evaluation or service context

• they do not experience any form of racism in policy, research, evaluation and service

contexts or processes

A deeper level of self-examination than reflective practice, focusing on the practitioner’s own biases, assumptions, and influence on their work in order to develop a more nuanced and ethical approach to their work.

About the authors

name: Dr Shirley Godwin

institution: La Trobe University

Dr Shirley Godwin is a proud Badimaya Yamatji woman whose unceded Country is located in what is now known as the central wheatbelt area of Western Australia. Shirley’s early professional career was spent in health research, initially in a biomedical research lab and then in Community-based Aboriginal health research. Since completing a MBBS at the University of Melbourne in 2010, Shirley has been working in First Nations health and Cultural Safety education, firstly with medical students and GPs-in-training in WA, and now across a range of health disciplines as a Senior Lecturer at the La Trobe University Rural Health School. The focus of this work is to support a decolonised curriculum that challenges power inequities to privilege First Nations voices, facilitate self-determination, and apply strength-based approaches to create culturally safe teaching and learning spaces.

Cultural safety for First Nations peoples requires an analysis of power relations to create an environment where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples report that:

• their experiences are believed and validated

• their cultures are centred and valued in policy development, research, evaluation

and service design and delivery

• they feel welcomed and respected in policy, research, evaluation and service

environments

• they see other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people working in the policy,

research, evaluation or service context

• they do not experience any form of racism in policy, research, evaluation and service

contexts or processes

A deeper level of self-examination than reflective practice, focusing on the practitioner’s own biases, assumptions, and influence on their work in order to develop a more nuanced and ethical approach to their work.

name: Dr Andrew Buldt

institution: La Trobe University

Dr Andrew Buldt is a senior lecturer from the Discipline of Podiatry at La Trobe University, Andrew also coordinates a large core first year subjects for first year undergraduate students enrolled in Allied health, nursing and health science degrees.

Cultural safety for First Nations peoples requires an analysis of power relations to create an environment where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples report that:

• their experiences are believed and validated

• their cultures are centred and valued in policy development, research, evaluation

and service design and delivery

• they feel welcomed and respected in policy, research, evaluation and service

environments

• they see other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people working in the policy,

research, evaluation or service context

• they do not experience any form of racism in policy, research, evaluation and service

contexts or processes

A deeper level of self-examination than reflective practice, focusing on the practitioner’s own biases, assumptions, and influence on their work in order to develop a more nuanced and ethical approach to their work.

name: Steven Chang

institution: La Trobe University

Steven Chang coordinates open education programs at the La Trobe eBureau. His focus is on empowering teaching academics and professional staff as emerging open practitioners through collaborative ‘Third Space’ projects. Steven is a Co-Convenor of the Open Educational Practices ASCILITE special interest group. His current role is Coordinator, Open Education & Scholarship at La Trobe University.

Cultural safety for First Nations peoples requires an analysis of power relations to create an environment where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples report that:

• their experiences are believed and validated

• their cultures are centred and valued in policy development, research, evaluation

and service design and delivery

• they feel welcomed and respected in policy, research, evaluation and service

environments

• they see other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people working in the policy,

research, evaluation or service context

• they do not experience any form of racism in policy, research, evaluation and service

contexts or processes

A deeper level of self-examination than reflective practice, focusing on the practitioner’s own biases, assumptions, and influence on their work in order to develop a more nuanced and ethical approach to their work.

name: Sebastian Kainey

institution: La Trobe University

Digital Discovery Officer (Library)

Cultural safety for First Nations peoples requires an analysis of power relations to create an environment where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples report that:

• their experiences are believed and validated

• their cultures are centred and valued in policy development, research, evaluation

and service design and delivery

• they feel welcomed and respected in policy, research, evaluation and service

environments

• they see other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people working in the policy,

research, evaluation or service context

• they do not experience any form of racism in policy, research, evaluation and service

contexts or processes

A deeper level of self-examination than reflective practice, focusing on the practitioner’s own biases, assumptions, and influence on their work in order to develop a more nuanced and ethical approach to their work.

name: Wendy Ratcliffe

institution: La Trobe University

Wendy is a Librarian with 30 years of experience in academic libraries, having held various roles at La Trobe University, including subject liaison and learning services. Currently, she serves as a Senior Coordinator in the Learning Support team, overseeing the delivery of On-Demand support to the LTU community across LTU’s six campuses, both virtually and in person. Wendy also manages subject-specific support for health streams within the La Trobe Rural Health School, Allied Health, Sport Science, Agriculture, Biomedicine, and Environment. Her main goal is to enhance the student experience by developing academic, information, and digital literacy skills, ensuring student success and fostering lifelong learning.

Cultural safety for First Nations peoples requires an analysis of power relations to create an environment where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples report that:

• their experiences are believed and validated

• their cultures are centred and valued in policy development, research, evaluation

and service design and delivery

• they feel welcomed and respected in policy, research, evaluation and service

environments

• they see other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people working in the policy,

research, evaluation or service context

• they do not experience any form of racism in policy, research, evaluation and service

contexts or processes

A deeper level of self-examination than reflective practice, focusing on the practitioner’s own biases, assumptions, and influence on their work in order to develop a more nuanced and ethical approach to their work.

name: Vivian Luker

institution: RMIT University

Vivian Luker is an Information Literacy Librarian at RMIT University. Vivian works with vocational, undergraduate and masters by coursework students to improve their search and information literacy skills and equip them for study at university.

Cultural safety for First Nations peoples requires an analysis of power relations to create an environment where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples report that:

• their experiences are believed and validated

• their cultures are centred and valued in policy development, research, evaluation

and service design and delivery

• they feel welcomed and respected in policy, research, evaluation and service

environments

• they see other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people working in the policy,

research, evaluation or service context

• they do not experience any form of racism in policy, research, evaluation and service

contexts or processes

A deeper level of self-examination than reflective practice, focusing on the practitioner’s own biases, assumptions, and influence on their work in order to develop a more nuanced and ethical approach to their work.

name: Melissa Digiacomo

institution: La Trobe University

Melissa Digiacomo is a Senior Learning Librarian at La Trobe University. Melissa collaborates with academic staff to design and create constructively aligned, student-centred learning experiences, supporting students to develop discipline-specific information and digital literacy skills. In her role, she also works with academic staff and the Library’s Scholarly Collections Team to ensure students have equitable access to prescribed library resources, promoting the inclusion of Open Educational Resources.

Cultural safety for First Nations peoples requires an analysis of power relations to create an environment where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples report that:

• their experiences are believed and validated

• their cultures are centred and valued in policy development, research, evaluation

and service design and delivery

• they feel welcomed and respected in policy, research, evaluation and service

environments

• they see other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people working in the policy,

research, evaluation or service context

• they do not experience any form of racism in policy, research, evaluation and service

contexts or processes

A deeper level of self-examination than reflective practice, focusing on the practitioner’s own biases, assumptions, and influence on their work in order to develop a more nuanced and ethical approach to their work.

name: Emerson Taylor

institution: La Trobe University

Emerson Taylor is a Learning Librarian at La Trobe University. He completed his Master of Information Studies at Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington in 2023. In 2024 he published ‘Depiction of library use in video games: a content analysis’ with Dr Chern Li Liew in the Journal of Documentation.

Cultural safety for First Nations peoples requires an analysis of power relations to create an environment where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples report that:

• their experiences are believed and validated

• their cultures are centred and valued in policy development, research, evaluation

and service design and delivery

• they feel welcomed and respected in policy, research, evaluation and service

environments

• they see other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people working in the policy,

research, evaluation or service context

• they do not experience any form of racism in policy, research, evaluation and service

contexts or processes

A deeper level of self-examination than reflective practice, focusing on the practitioner’s own biases, assumptions, and influence on their work in order to develop a more nuanced and ethical approach to their work.