19 Risk assessment process: Using analysis results

19.1 Chapter overview

By the end of this part you will:

- be able to distinguish between a control and treatment

- be able to use the control hierarchy to aid identification of treatments

- know how to test treatment options for their effectiveness in modifying uncertainty and its effects.

Cross reference to ISO31000 clause 6.3 and Annex SL clauses 6.1 and 8.1.

Check for key readings, webinars, and videos for complementary resources.

Definitions of italicised terms are in the Glossary.

Relevant law

- Health and Safety at Work Act 2015

- Health and Safety at Work (Worker Engagement, Participation, and Representation) Regulations 2016

- Health and Safety at Work (General Risk and Workplace Management) Regulations 2016

- Health and Safety at Work (Major Hazard Facilities) Regulations 2016

- Civil Defence Emergency Management Act 2002

Key questions

What is or will be the impact of artificial intelligence on the business?

If risk is the “effect of uncertainty on objectives“:

- what are the objectives of the organisation, activity, system, or item?

- what needs to be changed to make uncertainty or its effects acceptable?

Useful management techniques

The following techniques may help identify treatments that are practicable and reasonable.

- The treatment effectiveness rating can be used for a rough guide (see section 21.3.41).

- Bowtie analysis to identify control deficiencies or gaps (see section 21.3.3).

- Brainstorming to identify what might be practicable (see section 21.3.4).

- Cost-benefit analysis to identify whether an option would be “reasonable” (see section 21.3.8).

- Flowcharting an activity before and after treatment to identify changes (see section 21.3.13).

- Analysis of an activity using hierarchical task analysis before and after treatment to identify changes (see section 21.3.17).

- Risk velocity to identify changes before and after treatment to identify changes that will allow an effective, planned response (see section 21.3.36).

See the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 requirement for:

- the provision and maintenance of safe systems of work (section 36(3)(c) and section 2.2.3)

- the provision of “information, training, instruction or supervision” in section 36(3)(f).

Interventions will often need to be tailored to the specific context of the PCBU and activity (Karanikas et al., 2022; Workplace Health Expert Committee, 2021).

19.2 What is risk treatment?

Risk treatment is (ISO31073, 2022) a “process to modify risk”. Substituting for the definition of risk gives: a “process to modify the effect of uncertainty on objectives”. It is the identification, development and implementation of interventions.

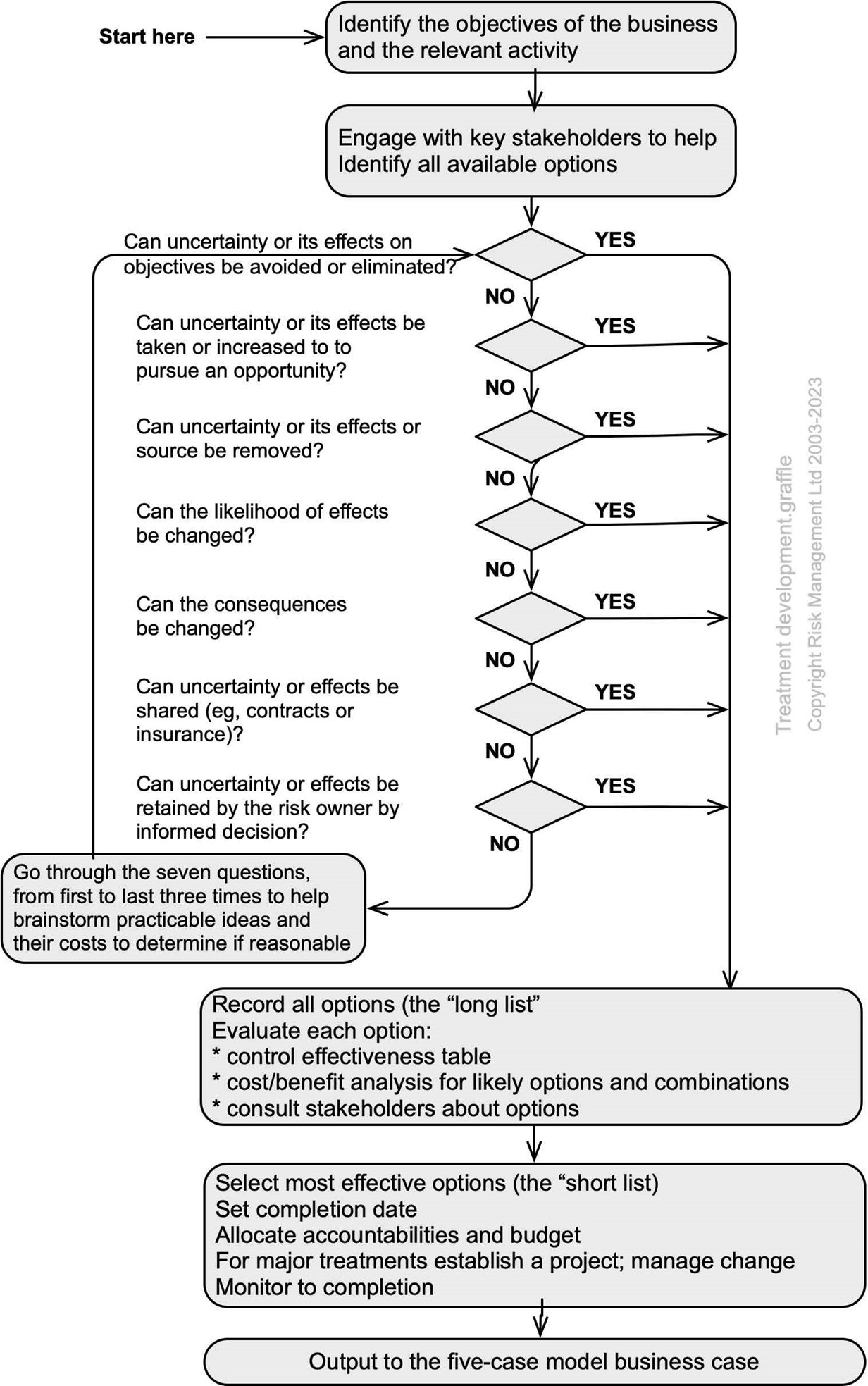

The first note to the definition of risk treatment states that treatment can involve “avoiding the risk by deciding not to start or continue with the activity that gives rise to the risk; taking or increasing risk in order to pursue an opportunity; removing the risk source; changing the likelihood; changing the consequences; sharing the risk with another party or parties [including contracts and risk financing]; and retaining the risk by informed decision”. This note to the definition was used to develop the hierarchy of control shown in Figure 16. Review the risk model (Figure 35, page 113) to see where uncertainty and its effect could be treated by modifying the context of the business or undertaking or activity, sources of uncertainty, initiating events, events, consequences, impacts on objectives and objectives. Compare that model with Figure 17, the Haddon model.

Important points

- When managing OHS, “sharing the risk” will require compliance with section 34 of the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015, to “consult, co-operate with and co-ordinate activities” when two or more PCBUs share a duty.

- Here, “informed decision” implies an effective assessment that provides the best available information, the weight of evidence; this will enable a decision maker to decide to give informed consent (Faden et al., 1986, pp. 274-275) to some proposed action.

- When completed, a treatment may become a control.

- Treatment may be needed if a control has failed or does not give the level of intended control.

- If uncertainty and its effect have been evaluated by comparing it with the relevant criteria and found not to be acceptable or tolerable “as is” they must be treated, even if by making an informed decision to retain it “as is” (but this may be highly unacceptable to WorkSafe or a District Court judge).

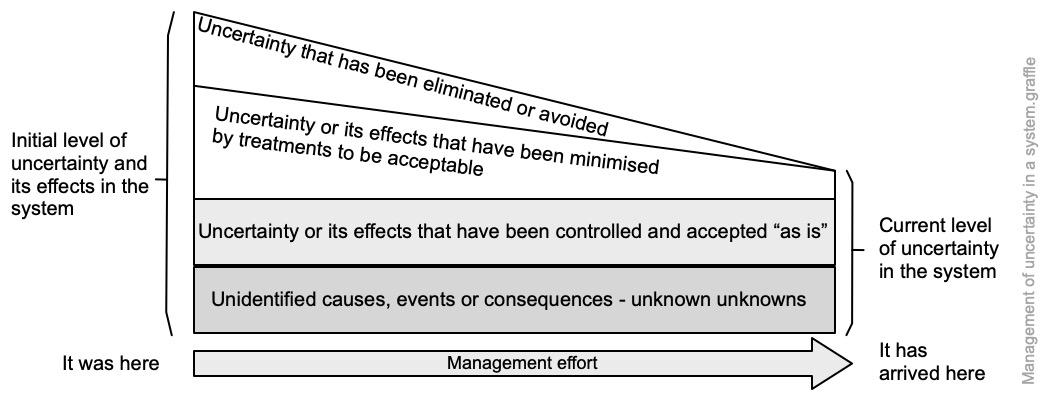

Visualising the current level of uncertainty

A way of conceptualising uncertainty is shown in the following diagram. Reading down the diagram, some uncertainty (the top wedge) has been eliminated or avoided, some was already minimised to an acceptable level and others can be treated to bring them to an acceptable level. The initial level of uncertainty is on the left-hand side of the diagram and current level on the right-hand side. Is this current level of uncertainty acceptable? If it is health or safety-related uncertainty, has it been minimised “so far as is reasonably practicable”? And what of the effects on objectives – the consequences?

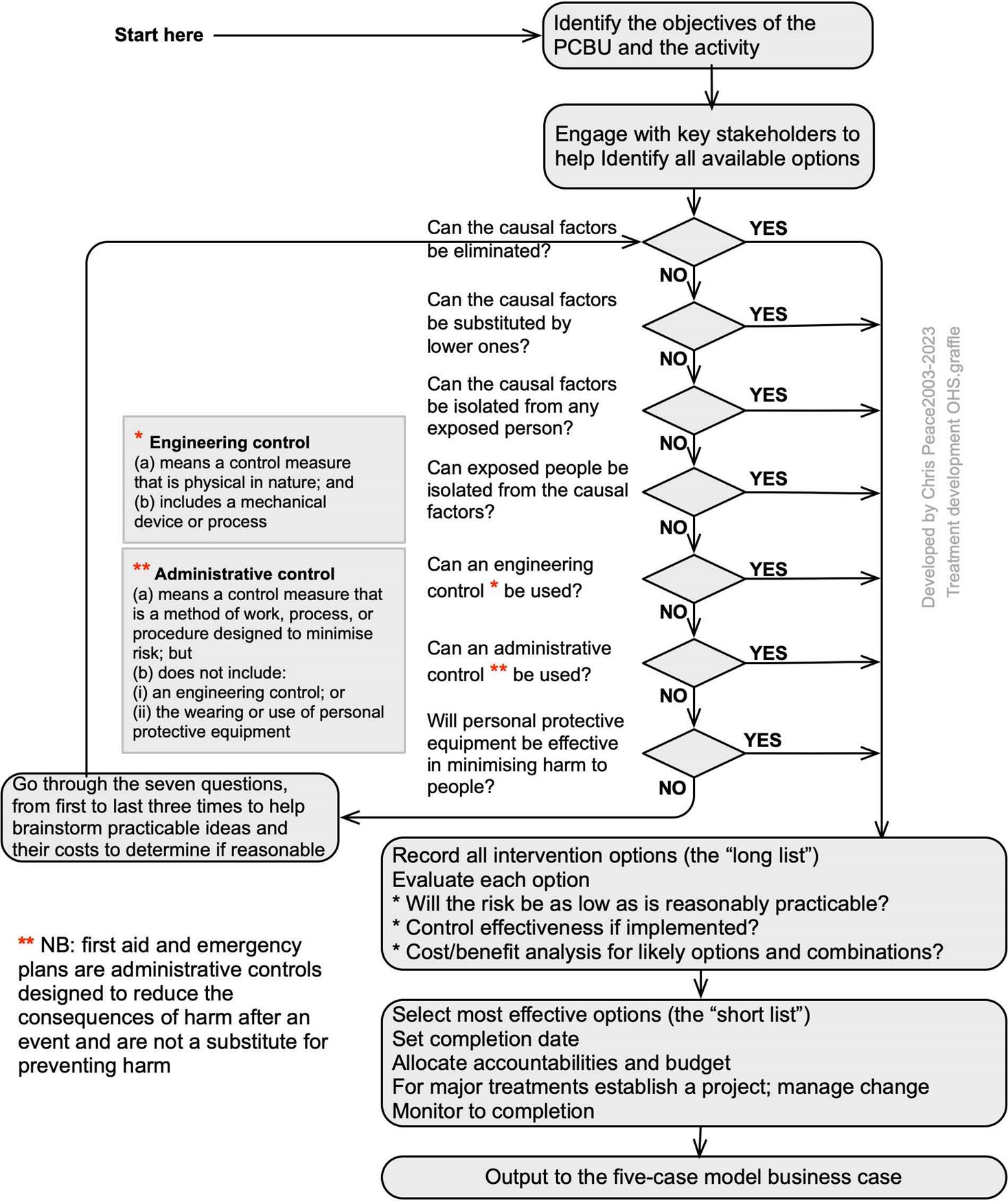

19.2.1 Identifying treatments for unacceptable uncertainty with effects on OHS objectives

Use either Figure 57 for uncertainty and its effects on OHS-related objectives, or Figure 58 for uncertainty and its effects with no OHS-related objectives. When OHS could be severely affected use both decision processes and the Haddon model to help give a high level of assurance that all practicable options that are reasonable have been considered.

Identifying OHS-related treatment or intervention options

Figure 57 sets out a generic process for the development of health- or safety-related controls using definitions in Regulation 3 and the hierarchy of control set out in Regulation 6 of the Health and Safety at Work (General) Regulations 2016. It assumes options will be addressed in a workshop using the best available information and weight of evidence from assessments. The output from this flowchart can be used to justify the best treatment options or as input to a business case.

Administrative controls include safe systems of work (HSWA section 36(3)(c)) and Information, training, instruction, or supervision (HSWA section 36(3)(f)). First aid and emergency plans (sections 7.4 and 17.3.7) are also regarded as administrative controls that may reduce the consequences of an event.

19.2.2 Identifying non-OHS treatment or intervention options

Figure 58 is a decision tree based on the definition of risk treatment that identifies the stages in identifying options for treatments or interventions when the effects of uncertainty other than on people have been assessed as unacceptable. The output from this flowchart can be used to justify the best treatment options or as input to a business case.

Retaining by informed decision

The option to retain the uncertainty and its effects by choice arises if, for example, an organisation currently lacks the resources or technology to treat a risk. The risk must then be retained until the resources or technology become available. It may also apply to a safety-related risk that is as low as is reasonably practicable or tolerable and cannot be further modified.

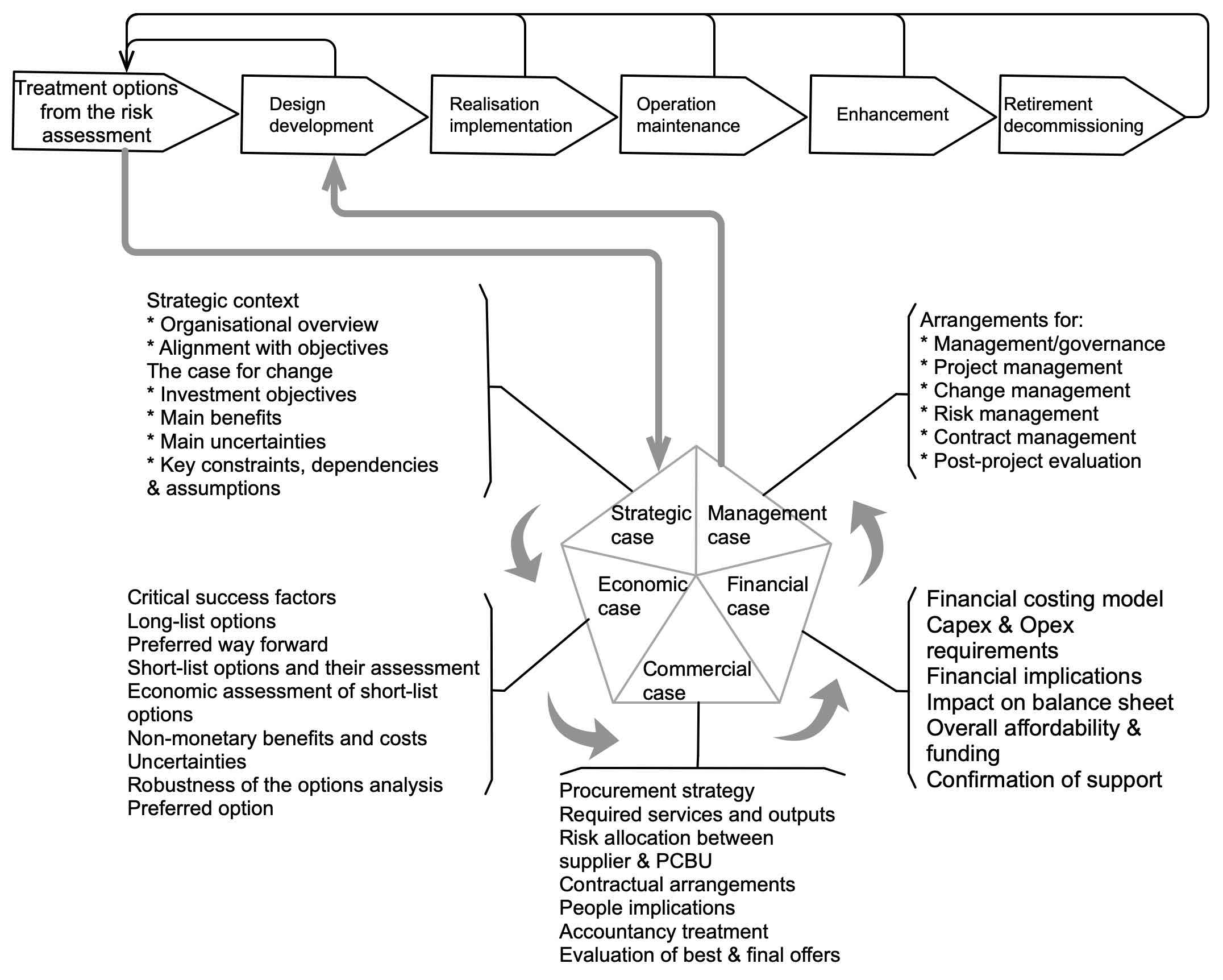

19.2.3 Developing a business case for treatments

This subsection is based on New Zealand Treasury Five Case Model framework (The Treasury New Zealand, 2023). Treatment or intervention options from either or both of the decision trees above act as the input to the strategic case. An alternative approach is in section 21.3.8.

Building the business case then moves anticlockwise in Figure 59:

- strategic case

- economic case

- commercial case

- financial case

- management case.

The output from the five cases is then used for development of a full business case for the most effective treatment or set of treatments. Note that issues discovered in the design and development phase may require the chosen treatment options and five cases to be reviewed and revised (AS/NZS IEC62198, 2015). Other issues throughout the process, including retirement or decommissioning, may also require review or revision of records.

Source: Adapted from The Treasury Five Case Model framework

Although not all treatments or interventions will require a full business case it is good practice to have a policy (sometimes called delegated financial authority) setting out when a business case is required. Such a policy also should set out who has authority to spend money under business-as-usual and emergency circumstances.

19.2.4 Improving human factors

The following are some solutions that may be both practicable and reasonable ways of eliminating or minimising performance variability and “human errors” – and possibly increasing productivity. They should form part of an overall safe system of work (Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 section 36(3)(c)).

Table 34. Performance shaping factors: some solutions

|

Performance shaping factors |

Solutions for such factors |

| Work environment stressors such as extremes of heat, humidity, noise, vibration, lighting, or workspace | Reduce the stressors and improve work environment conditions

Enable communication despite high noise levels |

| Social and organisation stressors such as inadequate staffing levels, work schedules, interpersonal conflicts, peer pressure and conflicting attitudes to health and safety | Address the conditions and reduce the stressors that increase the frequency of errors

Design jobs to avoid the need for tasks involving very complex decisions, diagnoses, or calculations (eg written procedures for rare events) |

| Personal stressors such an inadequate training and experience, fatigue, reduced alertness, family problems, ill-health, misuse of drugs or alcohol | Improve training and supervision, especially for inexperienced employees or for tasks where there is a need for independent checking

Ensure standard operating procedures and instructions are clear, concise, available, up-to-date, and accepted by or developed jointly with users Give workers appropriate personal protective equipment, branded for the organisation, to increase perceived status when worn in or outside the workplace |

| Equipment stressors such as poorly designed displays and controls, inaccurate and confusing instructions, and procedures | Design plant and equipment to prevent slips and lapses or to increase the chance of detecting and correcting them

Use better design to improve posture, usability of controls or equipment, access to working positions Improve reliability of instrumentation Improve alarm signalling and avoidance of false alarms |

| Extreme task demands such as workload, tasks demanding high levels of concentration, tasks that are monotonous or repetitive, situations with many distractions and interruptions | Ensure proper supervision, especially for inexperienced staff or for tasks where there is a need for independent checking

Monitor and review of tasks and jobs |

| Illogical or poorly written standard operating procedures resulting in “violations” of procedures or rules

Rules seen as restrictive in a given situation |

Review the rules to identify any that have become unnecessary or impractical

Explain the rules to help make them relevant Engage with workers to draw up rules agreed to be acceptable and practical |

| Jobs are seen as boring or limited | Use job enlargement to include additional tasks similar to those already being carried out (ie, horizontal job enlargement to multitasking)

Improve standard operating procedures (eg, language, layout, and ease of reading) Use job enlargement to include additional decision-making responsibilities or more challenging tasks (ie, vertical job enlargement to increase autonomy and variety) Form autonomous work groups given responsibility for achieving their group work objectives Use job rotation to increase task variety Seek simple, practicable changes to systems of work that have been designed by or in collaboration with employees |

| Incidents and near-hits are blamed on “human error” | Include human factors in all incident investigations

Get employees involved in risk assessments and incident investigations so they can identify deficiencies in equipment, systems of work and documentation, leading to practicable options for risk modification When a risk assessment or incident investigation has identified the need for capital expenditure, develop a business case, keep employees informed of progress and set dates for completion of changes |

Sector-specific examples include, for workplace transport (Harley & Cheyne, 2005), aircraft maintenance (Hobbs & Williamson, 1997), construction (Lunt et al., 2008), and major hazards industries (Simpson et al., 2003; Widdowson & Carr, 2002). Interventions and techniques for use in small and medium enterprises were described by Stephens et al. (2004).

19.3 Critical success factors for successful treatment of the effects of uncertainty

Research has shown the critical success factors for treatment are:

- multiple alternative options from which to choose the most effective option

- assumption testing before making the choice

- well-defined criteria and goals against which to test options

- dissent and debate about the risk, its assessment, and the treatment options before selecting options

- perceived fairness by all stakeholders.

19.4 Monitoring, review and reporting

Read clause 5.6 in ISO31000 (2009) or clause 6.6 in ISO31000 (2018).

19.4.1 Reporting on major or critical uncertainties and their effects

Major or critical risks (“extreme” despite current controls) are the “10 or so” risks that might be thought of as “life threatening” for an organisation. They should be reported to the Audit and Risk Committee or equivalent on a regular basis and in a common format. This will help “top management” (the “person or group of people who directs and controls an organisation at the highest level” – ie, directors, the executive management team or equivalent) to be kept sufficiently informed about such risks.

They then can challenge the risk owner (the “person or entity with the accountability and authority to manage a risk”) to give assurance that such risks are under effective management.

Outline report on an activity with high uncertainty

A report on the effects of such high uncertainties on objectives could be structured in different ways. The following example can be adapted to meet the specific needs of top management (including officers) and regulatory agencies. It draws on information gathered as part of an assessment using some of the techniques outlined in this book.

Each major “effect of uncertainty on objectives” is written up and tabled for top management review, one per month so that each is reviewed at least annually.

One page summary

A one-page plain English summary that sets out the following:

-

- the name of the activity having the potential to cause major harm or disruption

- the name of the “owner” of the activity

- who was engaged (ie, consulted) in the assessment

- the key background papers or sources of information

- key contextual issues found from the PESTLE analysis

- the current SWOT issues relevant to the effects of uncertainty

- major effects of uncertainty on key objectives

- the key controls and their effectiveness

- what else is being done to modify the uncertainties so its effects on objectives will be made more acceptable

- three sets of “traffic lights” showing the level of uncertainty with no controls, with current controls (at their known effectiveness), and after any further modification.

Bowtie analysis

A bowtie analysis showing:

-

- the key causal factors of an event and the consequences

- the controls currently in place

- the planned or “work in progress” risk modifications.

Appendices

Appendices summarising the background information that enabled the one-page summary and bowtie analysis. These need not be given to top management but should be available on request. They should be kept up-to-date and available for regulatory people to read.

19.5 Chapter Summary

This chapter has examined how to decide if the level of uncertainty and its effects are acceptable and, if unacceptable, how to identify and evaluate possible treatments.

When designing treatments remember they are interventions that will affect much more than the area under immediate consideration. Karl Popper, a famous philosopher/scientist, wrote something like:

We can never be certain about the consequences of our interventions. We can only narrow the area of uncertainty.

19.6 References used in this chapter

AS/NZS IEC62198: 2015 Managing risk in projects – Application guidelines, Standards New Zealand, Wellington.

Dekker, S. (2014). The Field Guide to Understanding ‘Human Error’ (3rd ed.). Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

Faden, R., Beauchamp, T., & King, N. (1986). A history and theory of informed consent. Oxford University Press.

Harley, R., & Cheyne, A. (2005). Review of key human factors involved in workplace transport accidents [Research Report RR0398]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Hobbs, A., & Williamson, A. (1997). Aircraft Maintenance Safety Survey – Results [Research Report sir199706_002]. http://atsb.gov.au/media/30080/sir199706_002.pdf

IEC62508: 2015 Human aspects of dependability, International Electrotechnical Commission, Geneva.

ISO31000: 2009 Risk management – Principles and guidelines, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

ISO31000: 2018 Risk management – Guidelines, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

ISO31073: 2022 Risk management — Vocabulary, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

Karanikas, N., Khan, S. R., Baker, P. R. A., et al. (2022, 2022/12/01/). Designing safety interventions for specific contexts: Results from a literature review. Safety Science, 156, 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2022.105906

Lunt, J., Bates, S., Bennett, V., et al. (2008). Behaviour change and worker engagement practices within the construction sector [Research Report RR0660]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Simpson, G., Tunley, C., & Burton, M. (2003). Development of human factors methods and associated standards for major hazard industries [Research Report RR0081]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Stephens, P., N, H., Gaskell, L., et al. (2004). Occupational health and SMEs: Focused intervention strategies [Research Report RR0257]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

The Treasury New Zealand. (2023, December 4). Better business cases. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/state-sector-leadership/investment-management/better-business-cases

Widdowson, A., & Carr, D. (2002). Human factors integration: Implementation in the onshore and offshore industries [Research Report RR0001]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Workplace Health Expert Committee. (2021). Evaluating interventions in work-related ill health and disease [Evidence Review Paper WHEC-17]. Health and Safety Executive, https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/workplace-health-expert-committee.htm