7 Planning to eliminate or minimise operational causes of harm

7.1 Chapter overview

Cross-reference to ISO31000; clause 8 in management system standards; and SafePlus requirements (section 2.2.5).

Definitions of italicised terms are in the Glossary.

Check for key readings, webinars, interviews, and videos for other resources.

Relevant law

- Health and Safety at Work Act 2015

- Health and Safety at Work (Worker Engagement, Participation, and Representation) Regulations 2016

- Health and Safety at Work (General Risk and Workplace Management) Regulations 2016

- Health and Safety at Work (Major Hazard Facilities) Regulations 2016

Key questions

What is or will be the impact of artificial intelligence on the business?

If risk is the “effect of uncertainty on objectives”:

- what are the operational or tactical objectives of the organisation, activity, system, or item?

- what are the uncertainties about achieving the objectives?

- how do or will those uncertainties affect achievement of the operational objectives?

Some readings

Potential content for general emergency plans is in the OHS BoK chapter on emergency management (Stanbury, 2019). There may be other requirements for emergency plans (eg, for evacuation following fire or earthquake) and there may be benefits in developing integrated plans (Borak & Silverstein, 1999; Byrne, 2012).

Useful management techniques

The following management techniques may help find information to develop operational plans to eliminate or minimise operational uncertainties or their effects on objectives.

- Fishbone or Ishikawa diagram (see section 21.3.12)

- Flowcharting or process mapping (see section 21.3.13)

- Goal tree (see section 21.3.15)

- HAZOP analysis (see section 21.3.15)

- Hierarchical task analysis (see section 21.3.17)

- MORT chart (see section 21.3.24.

7.1.1 Operational risk assessments

This chapter provides only a high-level summary of relevant material. See paper HLWB509 Identification, Assessment and Control of Hazards and Risks for more detail.

7.1.2 Operational controls: Development and application

Design of a safe system of work or standard operating procedure

Section 36(3)(c) HSWA requires a PCBU to provide and maintain safe systems of work and many prosecutions have led to District Court decisions that there was no such system or that any system was less than adequate. Little has been published about the meaning, design, implementation, and maintenance of a safe system of work although an article (Caponecchia & Wyatt, 2021) suggested a working definition, and a structured approach to the design of a safe system of work has been described (Braun et al., 2021). Further research into the term is needed.

Standard operating procedures seem to broadly fall into two types (Hale et al., 2012b):

… relatively static, rationalist, top–down view of rules as the one best way of working, devised by experts distant from the workplace, imposed on operators as a way of constraining incorrect or inadequate behaviour, where violations are seen as aberrations to be suppressed.

… relatively dynamic, bottom–up view of rules as local, situated, socially constructed, devised by those at the sharp end, embodying their tacit knowledge from their experience of diverse reality.

Note the similarity to system I and system II safety management (Dekker, 2014). This distinction requires that any safe system of work or standard operating procedure must be designed to avoid conflict with the culture of the PCBU.

Written standard operating procedures (a form of administrative control) are frequently used as part of a control system. If well written and implemented, they can be effective. However, they can also be a source of uncertainty with adverse consequences for occupational health or safety. Research (Praino & Sharit, 2016) focused “on the identification, understanding, and modelling of the risks potentially associated with written work procedures” arising from behavioural variability. They developed “a proposed modelling framework intended for translation or adaptation by organizations as a practical means for assessing what is referred to as ‘procedure risk’ – the risk resident in procedures”.

Decluttering

In a PCBU there may be conflicts between organisational policies and procedures, or excessive numbers of standard operating procedures. As part of any risk assessment or management review it may be found necessary to declutter operational controls (Adams, G. S. et al., 2021; HSE, 2019; Rae et al., 2018) to help ensure a focus on the key business objectives. Decluttering may also be known as business process reengineering.

7.1.3 Management of change

Basic management of change process

Any significant change to a system, process or organisation should be controlled by a management of change (MOC) process (CSB, 2001a) . This will require a document setting out:

- the context of the change to be managed (organisation chart, people, roles and responsibilities, culture, scope of the system, plant, design, processes, process variables, materials, equipment, procedures, software, design changes and external circumstances)

- relevant controls, proposed treatments and how implementation of the change and treatments will be monitored and how success will be measured

- the technical and managerial basis of each change and integration with other organisation and operational procedures

- a risk assessment for each change and all likely consequences of the changes

- engagement with all employees and contractors who might be affected by the change

- selection, training and (if necessary) qualification of employees and contractors whose jobs could be affected by the change before they interact with the changed process

- changes to any equipment or hardware starting with any conceptual and detailed designs, and acceptance tests

- updated standard operating procedures, drawings and other information affected by the change, including necessary consultation with workers or contractors

- descriptions summarising how the people, equipment and procedures will interact after the change

- if the change is temporary, a time limit for allowing the change to exist without further review.

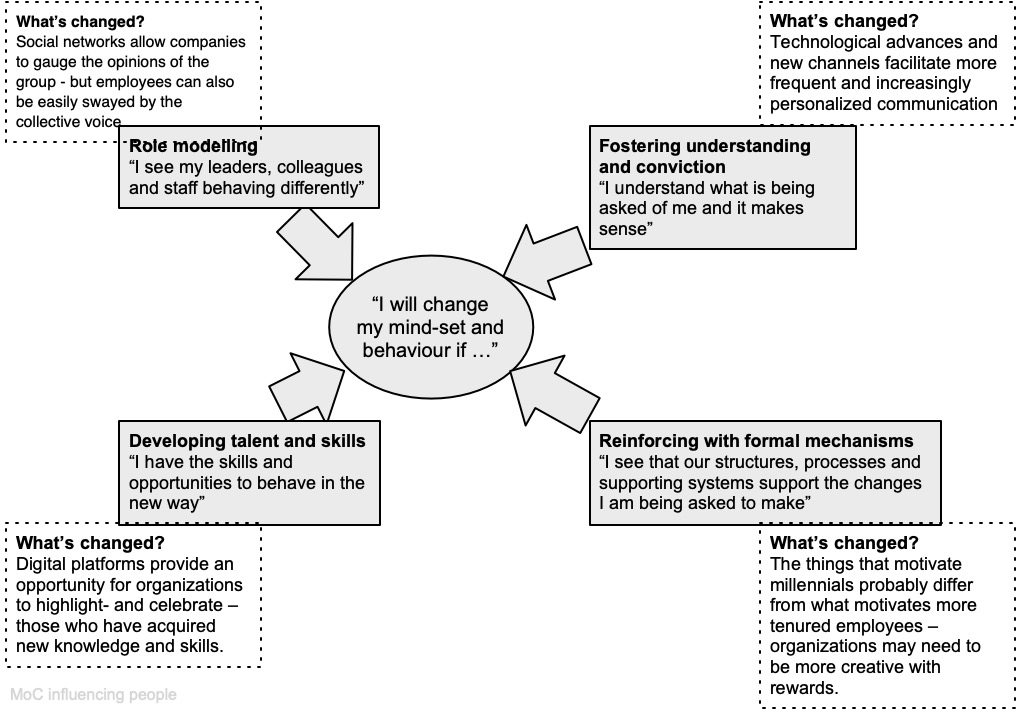

Winning hearts and minds for change

Any major change requires engagement with all employees and contractors who will be affected by the change. Figure 23 from McKinsey summarises how this might be done. Refer back to the McKinsey 7-S model (Figure 5) to see how change must operate across an organisation.

Two case studies

The US Chemical Safety Board (CSB) has published reports of investigations showing MOC processes that were less than adequate, including a refinery incident that occurred in 2001 at a refinery in Delaware City (CSB, 2001b) in which one worker was killed, eight were injured, and there was significant offsite environmental impact. The report identified the root and contributing causes of the incident and made recommendations on mechanical integrity, engineering management, management of change, and hot work systems.

Transport Accident Investigation Commission reports sometimes identify MOC systems that were less than adequate and that led to an incident. In a 2013 railway incident (Miskell, 2015) a passenger train travelling from Porirua to Wellington was derailed and four of the 315 passengers on board the train received minor injuries. A component from the train’s braking system had fallen onto the track, jammed against the underslung machinery and forced an air compressor up through the floor of one coach and into the passenger compartment. The component fell because, more than 10 weeks before the accident, maintenance staff had omitted to fit retaining split pins to bolts that were holding the component in place.

7.1.4 Nertney wheel

The Nertney Wheel (Nertney, 1987) represents people, equipment and procedures and the interfaces between each and can be used to aid development of a management of change system. See section 21.3.25.

7.2 Procurement of goods and services

See sections 39-43 Health and Safety at Work Act

7.3 Developing a compliance programme

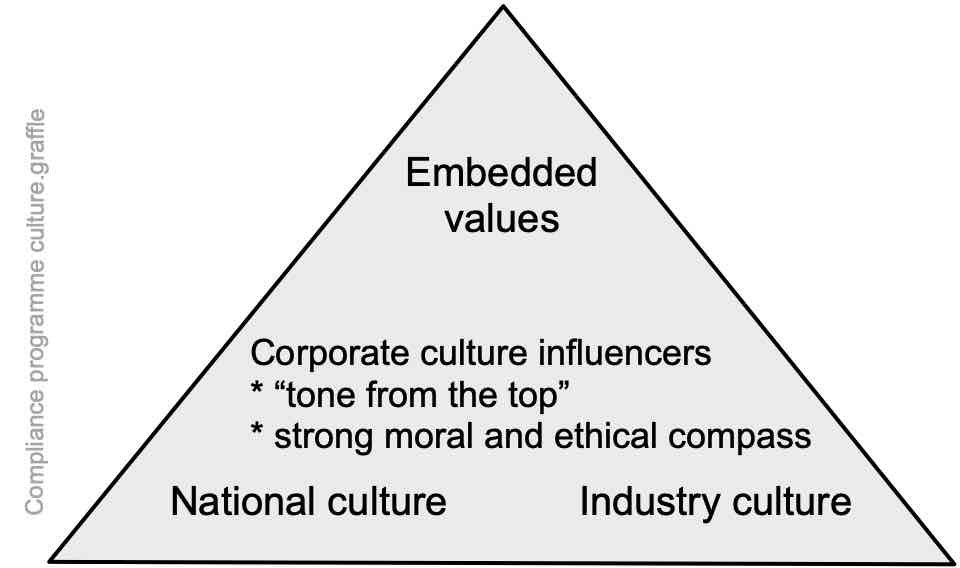

Developing a compliance programme is the first step in developing a compliance culture. The programme might be the “best ever developed”, but without a strong moral and ethical culture to support it (a “just culture” (Dekker, 2014, 2019; Reason, 1998)) the programme will fail.

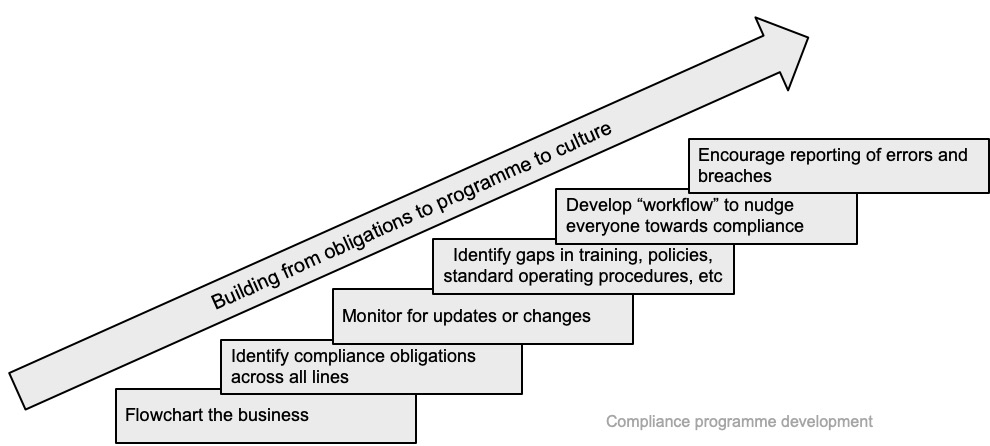

The following diagram illustrates development of a compliance culture, starting with an understanding of the business and context, process mapped in a workshop with a mix of subject matter experts and line managers. It includes “Trojan Horse messaging” to “nudge” workers to follow safe practices (Mark & Jeroen Van der, 2015; Sapsford et al., 2009; Steel Construction Institute, 2005; Thaler & Sunstein, 2008).

Compliance obligations are identified, and process mapped, starting with laws and regulations, then the organisational rules and finally the social norms the organisation is expected to follow.

Source: Author but inspired by Hammerich & Lewis (2013)

The pyramid summarises the cultural issues. The national and business sector cultures must be conducive to a compliance culture. This can be a significant problem for companies with foreign subsidiaries operating in a national or business culture where corruption or non-compliance is accepted.

The tone from the top must lead all managers and workers by encouraging development of embedded values of moral and ethical behaviour. A major test of this culture is that reporting of breaches is encouraged.

How can compliance be consistently achieved to an acceptable level?

There is no simple or single answer to this question, but the following table summarises some of the work done in one large organisation leading to an integrated approach to compliance 2001-2005. Breaches of the Commerce Act had previously resulted in fines in the order of $1.5 million. Matters were complicated because the business had workers and contractors who were engaged in physical works, and many customers, and competitors willing to take advantage of any adverse publicity. The organisation (and its competitors) remained subject to tight regulatory control by the Commerce Commission for several years.

Table 6. People, rules, techniques, and monitoring

| People | Rules | Risk techniques | Monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| Board mandate and senior management team commitment | Assess compliance obligation-related risks arising from: • NZ or business-as-usual sources • strategy- or project-related sources (might include foreign sources) • foreign legislation with local effects |

Establish a common language for: • risk • compliance • contingency or business continuity planning • safety • operational |

Routine reports to the senior management team, board and audit and risk committee |

| Promote a just reporting culture to ensure reporting of bad news | Establish core policies, standards, and guidelines | Develop a toolkit for assessment of compliance-related risks | Regularly review the risk and compliance management framework and processes |

| Set and clarify accountabilities | Integrate compliance in business-as-usual procedures and processes | Develop summaries of key compliance obligations | Develop and implement monitoring and reporting on compliance |

| Train relevant staff in assessment of compliance-related risks | Focus resources on higher risk areas | Integrate compliance-related rules in all forms of training (induction, on-the-job and task) | Plan and implement internal audits and control self-assessments |

| Train all staff to recognise compliance issues in their work | Document and communicate compliance-related rules and procedures | Create resource kits to enable self-help; include “who to ask for further information” | Encourage discussion and reporting of issues and near-hits |

| Train all staff in compliance obligations relevant to their work | Establish “if in doubt, ask” rules | Develop a learning management system | Monitor customer complaints and other feedback |

| Commend and reward complaint behaviour and creative enhancements

Penalise compliance failures |

Compliance obligations register | Establish annual plans to keep compliance fresh | |

| Develop and promote a compliance culture and as part of organisation values | Make compliance reporting part of all activities, including the annual report | ||

| Routine communications and awareness | Regular reporting to and contact with regulatory authority |

7.4 First aid and emergency preparedness

See section 17.4 for additional analysis of health and safety legislation and controls.

Regulation 13 of the HSW (General Risk and Workplace Management) Regulations 2016 sets out a duty to provide first aid. Provision of effective first aid may also help reduce the frequency of workplace injuries (Lingard, 2002; McKenna & Hale, 1981, 1982). Additional or specific first aid and rescue plans may be needed in some occupations (Adisesh et al., 2009) or activities (Selman et al., 2019), and members of the public using public transport may require post-event first aid (Miskell, 2016). Mental health has become a major occupational health issue. Mental health first aid has been advocated but with little evidence that it works (Bell et al., 2019; Workplace Health Expert Committee, 2021) and may need to be applied with care.

Table 7. Planning the development of first aid and emergency plans

|

Dimensionless rating |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reg. 14(3) & (4) requirements | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Nature of the work at the workplace | Office or similar sedentary work

|

Light engineering

Distribution centre |

Hard physical work

Construction

|

||

| Adventure activity examples | Guided walk over easy terrain | Bungee jumping | Kayaking during good weather | Whitewater rafting | Extreme adventure activity |

| Nature of the hazards at the workplace | Obvious slips, trips, and falls

Use of low-hazard substances |

Static plant | Highly hazardous substances, mobile plant, temperatures, or pressure

Work at heights, fast flowing, or cold water |

||

| Adventure activity examples | Slippery surfaces

|

Unstable slopes or cliffs | |||

| Size of the workplace | Small, single-storey building or open air

Single PCBU |

Large building or multiple buildings

Multiple PCBUs, difficult to coordinate |

|||

| Adventure activity examples | Well delimited or fenced area | No obvious boundaries | |||

| Location of the workplace | In an urban or suburban area, easy access for emergency services in 5-10 minutes | In a remote rural area; an hour or more for emergency services access or evacuation | |||

| Adventure activity examples | |||||

| Number of the workforce | Small, stable group | Large, dynamic group | |||

| Adventure activity examples | |||||

| Number of non-workers | Easy to control non-workers | Non-workers difficult to control | |||

| Adventure activity examples | |||||

| Composition of the workforce | Mature, experienced workers | ||||

| Adventure activity examples | |||||

| Characteristics of non-workers | Physically fit, | ||||

| Adventure activity examples | |||||

| Fire | No flammable material used in the workplace

Easy to walk away unaided from a fire to a safe place |

Highly flammable materials used in the workplace

Open flames are part of work |

|||

Regulation 14 of the HSW (General Risk and Workplace Management) Regulations sets out a duty to prepare, maintain, and implement emergency plans. Regulations 31-32 of the HSW (Major Hazard Facilities) Regulations sets out similar duties to prepare and test emergency plans. An emergency plan for a lower tier major hazard facility may form part of a plan developed under the General Regulations. The HSW General Regulations set out four parameters to be considered when developing first aid or emergency plans. These have been developed into the tentative model shown in Table 7. Detailed guidance is in WorkSafe (2020).

Table 7 is an incomplete model but is intended to draw attention to higher risks requiring greater first aid and more complex emergency planning. The table should be used twice, once for first aid planning and once for emergency planning.

NB 1: There is no evidence to support this model. It was developed to facilitate qualitative judgement using knowledge of the work and workplace under consideration.

NB 2: Sometimes it may be difficult to distinguish between the provision of first aid and development of effective emergency plans that incorporate first aid arrangements.

7.4.1 Emergency planning case studies

Read the following summaries and then use Table 7 to help show deficiencies.

The victim, a forestry worker, was breaking out at the cable logging forestry operation when they were pinned to the hill by the rope (WorkSafe NZ v Marris Couper Logging, 2018). There was no breaking out plan on the day of the incident and other workers had not been adequately informed of the site-specific hazards or the emergency plan. There was no equipment for the workers to measure safe retreat distances and the only form of communication was a radio. When workers were made aware of the incident, they stopped work and rescued the victim. However, the accident site was steep hill country with logging debris covering the ground making getting to the victim difficult. At no time was 111 called. The victim suffered fracture of the lateral tibia plateau to the left leg. This required four days hospitalisation including open reduction internal fixation surgery.

A kayak hire operator was prosecuted after two kayakers in a party of 11 died on Lake Tekapo (Maritime NZ v Ricky John Harnett t/a Aquanorts, 2016). The operator had not told Maritime NZ he was operating kayaks commercially and had not registered under the Maritime Operator Safety System (MOSS), so was not audited. He had inadequate safety systems in place and reacted too slowly to the emergency when windspeeds rose and conditions on the lake rapidly deteriorated. His safety briefing was inadequate as was his safety boat (source: SafeGuard January/February 2017).

7.4.2 First aid case studies

Read the following summaries and then use Table 7 to help show deficiencies.

Two dairy assistants were manually cleaning a stainless steel milk storage vat following milking, as the automatic cleaning system was broken (WorkSafe NZ v Point Blank Farms Ltd, 2014). To clean the vat, 10 litres of water were mixed with 20mls of “Avoid” (a heavy-duty alkaline cleaning product). One worker climbed into the vat to clear the walls of the vat and the other poured the mixed solution into the bottom of the vat. Upon completing cleaning she noticed her knee was burning. She was advised to place her knee in a bucket of warm water but to no avail. Then she was given Aquaklenz HV (an acidic heavy-duty cleaner) with warm water. The first aid the employee received was not as recommended on the safety data sheet for “Avoid”.

A tourist on a sightseeing trip to a glacier on the West Coast had one of her fingers partially amputated and other fingers crushed while getting into a helicopter with moving rotors (CAA v Alpine Guides Fox Glacier Ltd, t/a Fox Glacier Guiding, and Mountain Helicopters Fox Glacier Ltd, 2020). The tourist waved as she was getting back into the helicopter to fly back from the glacier and her hand was struck by the moving rotor of the helicopter, partially amputating the middle finger on her right hand. She received first aid at Fox Glacier Guiding’s base before an ambulance took her to a nearby medical centre. She was later released by the medical centre and her husband took her to a hospital in Greymouth. She was transferred to a hospital in Christchurch the next day, where she underwent surgery. She spent a total of three days in hospital. The CAA was critical of Fox Glacier Guiding’s response to the incident and questioned why arrangements were not in place to fly the woman to hospital. Fox Glacier Guiding denied its response was inadequate and said neither ambulance staff nor the medical centre staff considered the victim needed to be flown to a hospital.

The PCBU and the director of the business were prosecuted after a student hang glider pilot died while being towed behind a car on beach south-west of Auckland (CAA v Aqua Air Development and Patrick Neil Monro, 2020). The student became airborne, rising to 30-50 metres when they should have been limited to two metres. The student experienced a lockout (a sideways drift), could not regain control, fell to the beach, and died at the scene from blunt force trauma. The small first aid kit was inadequate, there was no mobile phone coverage, and the nearest medical help was about 30 minutes away.

7.5 Chapter summary

This chapter has outlined some aspects of planning operational procedures to eliminate or minimise harm to workers and “other persons” whose health and safety might be put at risk by the conduct of the business or undertaking. The weaknesses of administrative controls and reliance on personal protective equipment are emphasised.

7.6 References used in this chapter

Adams, G. S., Converse, B. A., Hales, A. H., et al. (2021). People systematically overlook subtractive changes. Nature, 592(7853), 258-253. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03380-y

Adisesh, A., Robinson, L., Codling, A., et al. (2009). Evidence-based review of the current guidance on first aid measures for suspension trauma [Research Report RR0708]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Basford, T., & Schanginger, W. (2016, April). The four building blocks of change. McKinsey Quarterly. http://www.mckinsey.com/

Bell, N., Evans, G., Beswick, A., et al. (2019). Summary of the evidence on the effectiveness of Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) training in the workplace [Research Report RR1135]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Borak, J., & Silverstein, B. D. (1999). Emergency response plans: The benefits of integration. Occupational Hazards, 61(9), 44-48.

Braun, C., Brophy, S., Jassim, M., et al. (2021). A structured approach to the concept of a safe system of work. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 46(2), 4-19. https://doi.org/10.24135/nzjer.v46i2.64

Byrne, R. (2012, August). Keep calm and carry on. Safety & Health Practitioner, 38-40.

CAA v Alpine Guides Fox Glacier Ltd, t/a Fox Glacier Guiding, and Mountain Helicopters Fox Glacier Ltd [2020] Christchurch District Court. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/crime/122914687/tourists-finger-partially-amputated-by-helicopter-rotor

CAA v Aqua Air Development and Patrick Neil Monro [2020] Manukau District Court.

Caponecchia, C., & Wyatt, A. (2021). Defining a “safe system of work”. Safety and Health at Work, 12(4), 421-423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2021.07.001

CSB. (2001a). Management of change [Bulletin]. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board, Washington, DC. http://www.csb.gov/

CSB. (2001b). Refinery Incident – Motiva Enterprises LLC [Incident Investigation report 2001-05-I-DE]. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board, Washington, DC. http://www.csb.gov/

Dekker, S. (2014). The Field Guide to Understanding ‘Human Error’ (3rd ed.). Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

Dekker, S. (2019). Foundations of safety science: A century of understanding accidents and disasters. CRC Press.

Fire and Emergency New Zealand (Fire Safety, Evacuation Procedures, and Evacuation Schemes) Regulations 2018. https://www.legislation.govt.nz/regulation/public/2018/0096/latest/LMS46332.html?search=y_regulation%40regulation_2025_2018_rc%40rinf%40rnif_an%40bn%40rn_25_a&p=1

Hale, A., Borys, D., & Else, D. (2012b). Management of safety rules and procedures: A review of the literature [Research Report 12.1]. IOSH Publishing Ltd, Wigston. www.iosh.co.uk

Hammerich, K., & Lewis, R. (2013). Fish can’t see water: How national culture can make or break your corporate strategy. John Wiley & Sons.

HSE. (2019). Understanding the impact of business-to-business health and safety ‘rules’ [Research Report]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Health and Safety at Work (General Risk and Workplace Management) Regulations 2016. https://www.legislation.govt.nz/regulation/public/2016/0013/latest/DLM6727530.html?search=ta_regulation%40regulation_H_rc%40rinf%40rnif_an%40bn%40rn_25_a&p=2

Lingard, H. (2002). The effect of first aid training on Australian construction workers’ occupational health and safety motivation and risk control behavior. Journal of Safety Research, 33(2), 209-230. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4375(02)00013-0

Maritime NZ v Ricky John Harnett t/a Aquanorts [2016] Queenstown District Court.

Mark, K., & Jeroen Van der, H. (2015). From mechanism to virtue: Evaluating Nudge theory. Evaluation, 21(3), 276-291. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389015590218

McKenna, S. P., & Hale, A. (1981). The effect of emergency first aid training on the incidence of accidents in factories. Journal of Occupational Accidents, 3(2), 101-114. https://doi.org/10.1016/0376-6349(81)90003-1

McKenna, S. P., & Hale, A. (1982, 6//). Changing behaviour towards danger: The effect of first aid training. Journal of Occupational Accidents, 4(1), 47-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/0376-6349(82)90055-4

Miskell, P. (2015). Derailment of metro passenger Train 8219 Wellington [Investigation Report 13-104]. Transport Accident Investigation Commission, Wellington. www.taic.org.nz

Miskell, P. (2016). Passenger train collisions with Melling Station stop block [Incident Investigation report RO-2014-103]. Transport Accident Investigation Commission, Wellington. http://www.taic.org.nz/

Nertney, R. (1987). Process Operational Readiness and Operational Readiness Follow-on [Working Paper]. System Safety Development Center, EG&G, Idaho Falls, ID.

Praino, G., & Sharit, J. (2016, 2//). Written work procedures: Identifying and understanding their risks and a proposed framework for modeling procedure risk. Safety Science, 82, 382-392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2015.10.002

Rae, A., Provan, D., Weber, D. E., et al. (2018). Safety clutter: the accumulation and persistence of ‘safety’ work that does not contribute to operational safety. Policy and Practice in Health and Safety, 16(2), 194-211. https://doi.org/10.1080/14773996.2018.1491147

Reason, J. (1998). Achieving a safe culture: Theory and practice. Work & Stress, 12(3), 293-306. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678379808256868

Sapsford, D., Pythian-Adams, S., & Apps, E. (2009). Behavioural economics: A review of the literature and proposals for further research in the context of workplace health and safety [Research Report RR0752]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Selman, J., Spickett, J., Jansz, J., et al. (2019, 2019/03/01/). Confined space rescue: A proposed procedure to reduce the risks. Safety Science, 113, 78-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2018.11.017

Stanbury, A. (2019). Emergency management. In Core Body of Knowledge for Generalist OHS Professionals. Australian Institute of Health and Safety. https://www.ohsbok.org.au/

Steel Construction Institute. (2005). Trojan horse construction site safety messages [Research Report RR0336]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrhtm/index.htm

Thaler, R., & Sunstein, C. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth and happiness. Yale University Press.

Workplace Health Expert Committee. (2021). Evaluating interventions in work-related ill health and disease [Evidence Review Paper WHEC-17]. Health and Safety Executive, https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/workplace-health-expert-committee.htm

WorkSafe NZ. (2020). First aid at work [Guidance Note WKS17]. author, Wellington. http://worksafe.govt.nz

WorkSafe NZ v Marris Couper Logging [2018] Blenheim District Court. https://www.worksafe.govt.nz/laws-and-regulations/prosecutions/court-summaries/marris-couper-logging-limited/

WorkSafe NZ v Point Blank Farms Ltd [2014] Gore District Court. https://www.worksafe.govt.nz/laws-and-regulations/prosecutions/court-summaries/point-blank-farms-limited/