4 Leadership, engagement

4.1 Chapter overview

This chapter touches on material covered in detail in paper HLWB511 Health and Safety Management and Leadership.

Cross reference to ISO31000; ISO45001; Annex SL clause 5; and SafePlus (section 2.2.5).

Definitions of italicised terms are in the Glossary.

Check for key readings, webinars, interviews, and videos for other resources.

Relevant law

- Health and Safety at Work Act 2015

- Health and Safety at Work (Worker Engagement, Participation, and Representation) Regulations 2016

- Health and Safety at Work (General Risk and Workplace Management) Regulations 2016

- HSW (Major Hazard Facilities) Regulations 2016

Key questions

What is or will be the impact of artificial intelligence on the business?

If risk is the “effect of uncertainty on objectives”:

- what are the objectives of the organisation, PCBU, activity, system, or item?

- what are the uncertainties about achieving the objectives?

- how do or will those uncertainties affect achievement of those objectives?

- how should those uncertainties be overcome by leadership and engagement?

Useful management techniques

The following techniques will help identify leaders, from the front line to the boardroom, and who to engage with about uncertainty.

- 5W1H (section 21.3.1)

- Fishbone or Ishikawa analysis (section 21.3.12)

- Literature or document review (section 21.3.22)

- Organisation charts (section 21.3.25)

- SWOT analysis (section 21.3.39).

4.2 Leadership, roles and engagement

Who are the leaders? How do they exhibit leadership? One way of identifying “leaders” is to look at the organisation (org) chart for a PCBU. In a large organisation spread across several sites this can be a very useful starting point. However, sometimes org charts are out of date or very high-level. Peters & Waterman (1982) found that:

… the stronger the culture and the more it was directed to the marketplace, the less need there was for policy manuals, organisation charts, or detailed procedures and rules. In these companies people way down the line know what they are supposed to do in most situations because the handful of guiding values is crystal clear.

Often, one worker will be found to be a leader in their own area of expertise and their sphere of influence may show that senior managers defer to them.

Research by Bell et al. (2014) has shown that engaged workers exhibit “citizenship behaviours” including:

- thinking positively about their workplace

- seeking out ways to support organisational objectives and values

- performing core tasks to a higher standard than expected.

These behaviours contribute to reducing absenteeism (Mellor et al., 2008), making suggestions about their work and potential innovations (Barsh et al., 2008), and potentially leading to improved productivity and profits.

Bell et al. (2015) cite several HSE research reports and a substantial report (Macleod & Clarke, 2009) to the UK government on engagement; the latter was proposed as a way of improving the overall performance of UK industry.

Two strategies for improving worker engagement in the UK (Bell, Lekka, et al., 2015) were found to be risk profiling (identifying the ‘top five’ OHS risks in a business or undertaking) and safety observation cards (effective in businesses that understood their risk profile). In this study the benefits of worker engagement were similar to those found in earlier studies but included repeat business and a reduction in workplace injuries. Improvements required long-term persistence of senior managers in driving change and overcoming resistance of team leaders. The study concluded that “training leaders at all levels in worker involvement techniques” was essential.

4.3 Leadership style

If leadership is the key to worker engagement, what are the characteristics of positive leadership?

An early article by Cohen (1977) included the following factors associated with successful safety programmes.

Strong management commitment to safety as defined by various actions reflecting management’s support and involvement in safety activities.

Close contact and interaction between workers, supervisors, and management enabling open communications on safety as well as other job-related matters.

Management commitment to safety was believed a major, controlling influence in attaining success in industrial accident prevention efforts. Open communication between workers, supervisors, and management was also considered of great significance.

A follow-up article (Smith, M. J. et al., 1978) reported additional differences in safety programme practices that could account for plant safety performance. The data indicated that the low accident companies differed from their matched high accident rate partners in the following ways:

(1) greater management commitment and involvement in the safety program and safety matters

(2) a more humanistic approach in dealing with employees stressing frequent positive contact and interaction

(4) more frequent use of lead workers to train employees versus supervisors

Some of the factors in these two articles show leadership while others can be seen as outcomes of leadership.

The need for leadership in OHS in medical settings (Flin & Yule, 2004) drew on earlier work in the energy and manufacturing sectors, emphasising that effective performance required leadership by senior managers, middle managers and team leaders. These behaviours have been drawn from the empirical research reviewed in the paper and classified according to transactional/ formational leadership theory.

An open access review of 40 papers (Lekka, 2013) found consistent relationships between specific leadership styles and safety outcomes. The review had important implications for practice, including:

- managers should adopt a transformational leadership style, supported by a transactional style

- these should be supported by training in such skills

- managers need to actively demonstrate a commitment to safety

- leaders should use trustworthy communications to workers.

The research also identified the need for further research in high-hazard industries.

Further work by Clarke (2013) showed that transformational and transactional leadership styles are antecedents of safety behaviours and influence absenteeism (Mellor et al., 2008). Later work (Mattson Molnar et al., 2018) demonstrated the effect of a leader who:

- “gives priority to safety over other aspects’ speed and schedules

- has a proactive focus on safety work procedures and not only on the end product (ie. absence of accidents and injuries)

- keeping track of potential risks and routine safety problems apart from major problems

- overt reactions to subordinates’ conduct, ie positive and negative feedback

- initiation of actions concerning safety improvements

- communicating safety issues and values during everyday work”.

Five safety leadership styles, attributes and behaviours were described by Donovan et al (2018):

- transformational

- transactional

- empowering

- authentic

- leader-member exchange.

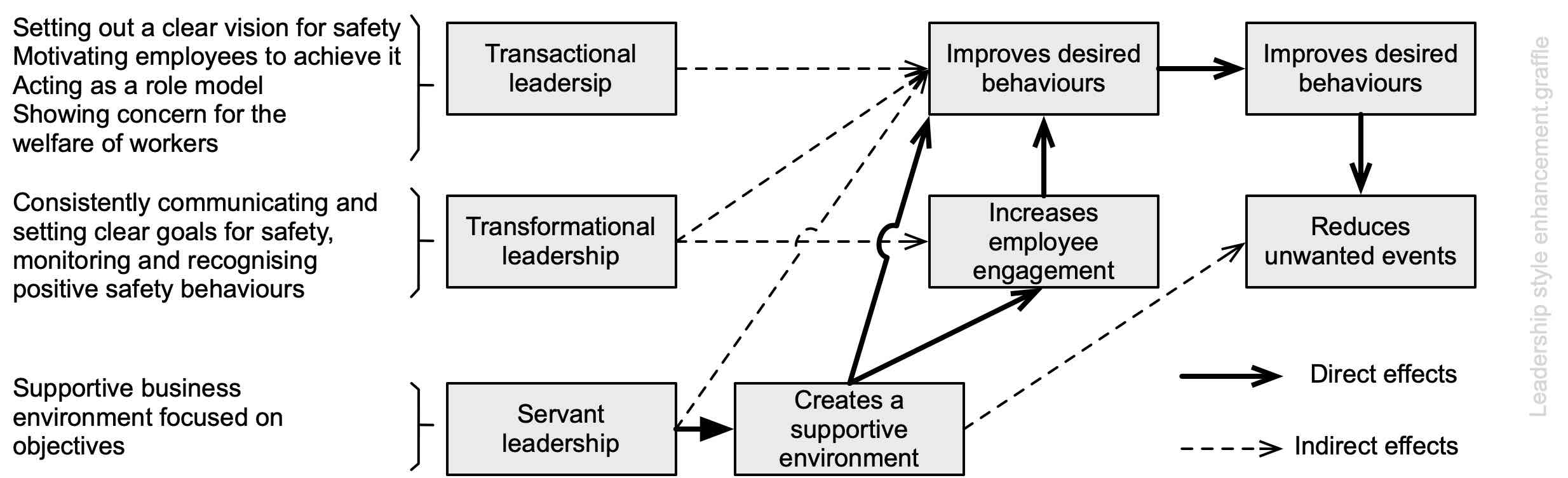

The effect of these leadership styles was summarised (Cooper, 2014) to show how transformational leadership has the greatest effect on behaviours, especially when supported by transactional and servant (ie, worker) leadership (Figure 10).

Source: Reproduced from Cooper (2014)

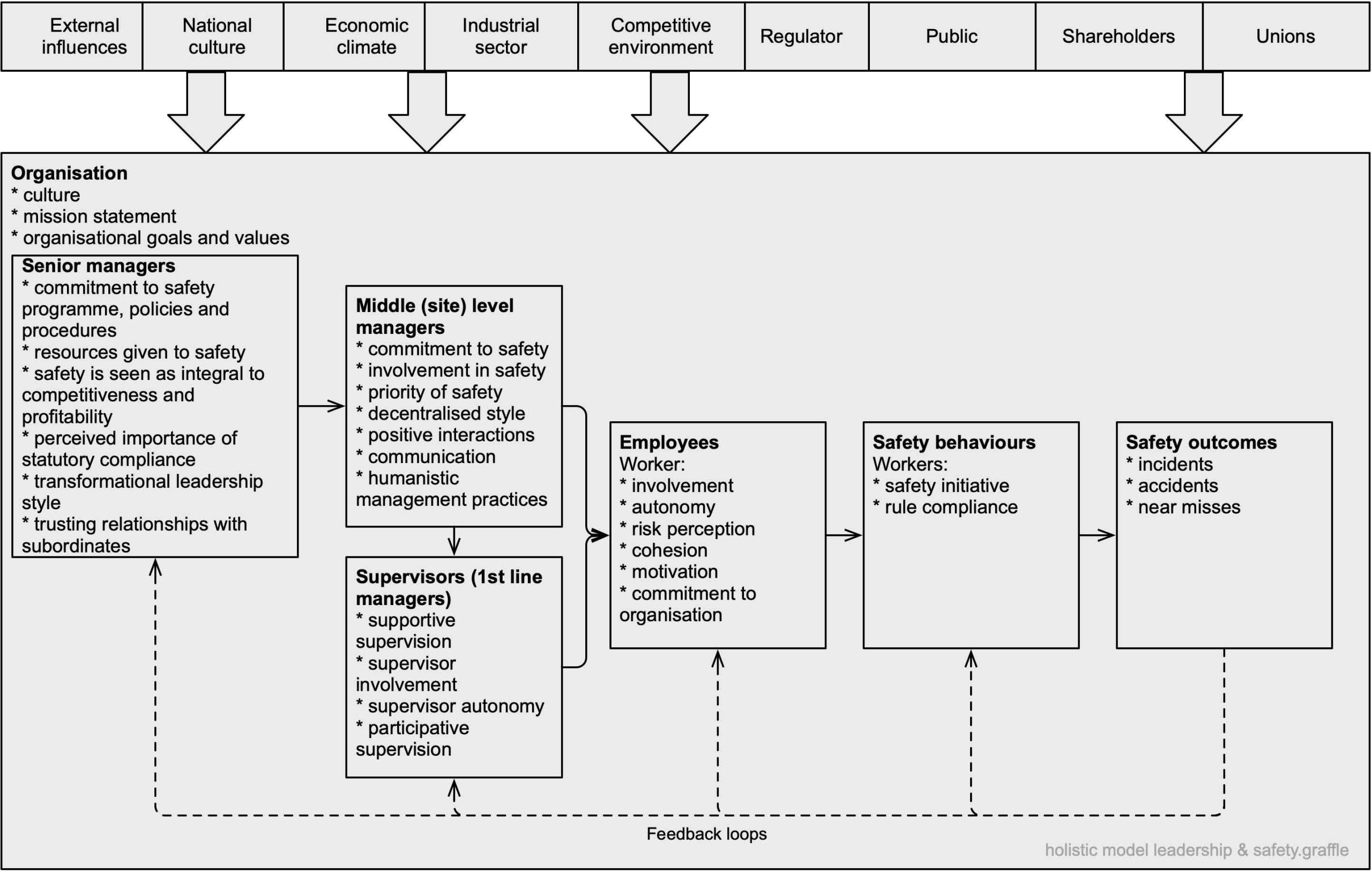

Research (O’Dea & Flin, 2003) in leadership factors at each management level led to development of a descriptive, holistic model for leadership and safety (Figure 11). Note that this model shows the range of factors external to an organisation that are likely to influence the overall culture of an organisation. Internal factors likely to have a strong influence on senior managers include mission statements, goals and values that affect the whole organisation (see the McKinsey 7-S model). Senior managers attitudes will influence middle managers who will, in turn, influence team leaders and workers. The model suggests incidents and injuries will influence future safety behaviours.

Source: Adapted from Figure 6.1 in O’Dea & Flin (2003). Contains public sector information published by the Health and Safety Executive and licensed under the https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/

Overall, the research suggests that transformational leadership, combined with transactional or contingent rewards and safety self-efficacy, lead to improvements in OHS. Such changes may be achieved by training leaders (von Thiele Schwarz et al.) but the overall effects of transformational leadership are incremental, taking many months (perhaps years) to be felt.

4.4 Roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities

4.4.1 Officers

In the UK, guidance recommended that directors lead OHS as this helped establish and maintain an effective culture. While most directors recognised this, a survey found that in 26% of the companies surveyed, health and safety was not led at director level (Miller, M. & Shearn, 2005). Reasons for director-led OHS included compliance, protection of reputation, “safety pays”, ethical or moral, and benchmarking against competitors.

A qualitative research report to the UK HSE (King et al., 2010) questioned:

1. What do directors/board members understand about the current legislative framework for health and safety?

2. What do directors/board members mean when they say they have taken action in the areas covered in the baseline study?

3. How and do board level actions translate into action on the ‘shop floor’ and genuine improvements in health and safety?

4. What is the impact of board level behaviour change from the perspective of health and safety managers?

5. Are there opportunities to influence behaviour?

Research (Boardman & Lyon, 2006) led to a best-practice framework showing seven principles thought to be fundamental to effective governance and contributed to an article on the requirements and implications of due diligence in section 44 HSWA (Peace et al., 2017).

O’Neill & Wolfe (2014) took a different perspective about due diligence, asking if the duty was an accounting problem.

Dabee (2020) argued that there was little guidance on compliance for officers. Was this primarily a problem for small and medium enterprises, did large businesses have access to substantial legal advice? In a Maritime New Zealand case Antonio Basile, an officer (the sole director of Nino’s Ltd) pleaded guilty in a prosecution by Maritime New Zealand to a breach of section 44. In his decision, Davidson J (Maritime NZ v Nino’s Ltd, Antonio Innocenzo Basile, Shane Michael McCauley, 2020) noted that:

The fishing boat was already substantially loaded with fish well in excess of the five-tonne load stability limit. A final catch, estimated to be something in the order of nine or 10 tonnes, in and of itself virtually doubling the stability limit, was being hauled on board.

The five tonnes operational limit should have been known to Basile when he purchased the trawler and should have been made known to the Master before the trawler sailed.

More recently, the section 44 duty has been clearly held to be that of an individual officer, not the board as a whole (WorkSafe NZ v Andrew Buttle, James Buttle & Peter Buttle, 2023).

[15] There is no evidence in this case of what happened behind the boardroom door at WML. There is no evidence of what discussions there may have been among the Buttles that touches on their circumstances and their responsibilities. Without that evidence, I cannot assess what a reasonable director would have done had they been placed in that director’s shoes.

[16] If WML had one director only, it would be straightforward to sheet any failures back to that one director. If there was evidence that the constitution of a PCBU required the actions and decisions of all directors to be unanimous and informed, you could perhaps sheet any failures of the PCBU back to each of the directors.

[17] But in the ordinary course of business, boards do not operate that way. They discuss, they negotiate, they disagree at times, they vote. The will of the board as a whole drives a company forward. How a company presents itself to the rest of the world reflects the will of the board as a whole, not the will of individual directors.

In contrast, in the prosecution of the ex-CEO (an officer as defined in HSWA) of Ports of Auckland, MNZ asserted that Mr Gibson had failed to meet his due diligence duties in two ways (Maritime NZ v Anthony Michael Gibson, 2024). The second was Mr Gibson did not take reasonable steps to ensure that health and safety resources were provided, and health and safety processes were followed (HSWA section 44(4) c and d). The District Court decision is long but a useful summary (Roberts, J. & Weatherall, 2024) showed that Mr Gibson did not take reasonable steps to ensure that health and safety resources were provided, and health and safety processes were followed (Particular 2).

“The key failing that led to Mr Gibson’s guilt in respect of Particular 2 was that POAL’s systems failed to identify and respond to work as done rather than work as planned. This was caused by ineffective monitoring of workers. To clarify, ‘work as done’ “is the reality of work as it is actually carried out by the workers on the ‘shop floor’” (at [324]). Essentially, this means, irrespective of policy or procedure, how, in practice, an organisation conducts its operations. ‘Work as planned’ or as it may be referred ‘work as imagined or intended’ refers to the methods of work “designed, understood or expected” by management and staff who do not undertake the work themselves (again at [324]).

Mr Gibson was aware that work at the Port was not being effectively monitored for health and safety compliance. Despite this knowledge, this shortcoming was not addressed. Implementation of a KPMG audit recommending that specific responsibilities be assigned to executives was delayed. A proposed change in team structure, which would have assigned expert coaches to specific groups of stevedores, enabling better monitoring, was abandoned. Finally, the Health and Safety Steering Committee, chaired by Mr Gibson, did not compare POAL’s health and safety performance against its policies and procedures. This meant the Committee could not confirm if workers were following the rules. Mr Gibson was able to control what POAL did in these areas. However, he failed to intervene, and monitoring remained ineffective.

Mr Gibson’s failure to ensure that work at the Port was effectively monitored meant that POAL was unable to determine whether health and safety procedures were being followed. Accordingly, dangerous practices such as corner cutting on night shifts were never addressed. This exposed POAL’s stevedores to the risk of death or serious injury. Accordingly, the Judge found that Mr Gibson had not taken reasonable steps to ensure that POAL’s safety procedures were followed”.

4.4.2 Leadership team

The leadership team is part of “top management” in a business or undertaking and is the “person or group of people who directs and controls an organisation at the highest level” (ISO/IEC Annex SL, 2020). Annex SL states that top management “has the power to delegate authority and provide resources within the organisation provided ultimate responsibility for the management system is retained”. If the scope of a management system “covers only part of an organisation, then top management refers to those who direct and control that part of the organisation”.

The definition of “officer” in section 18(b) of the HSWA includes “any other person occupying a position in relation to the business or undertaking that allows the person to exercise significant influence over the management of the business or undertaking (for example the chief executive)”. Other members of the leadership team of a PCBU might also be held to be officers.

4.4.3 Workers

For workers, changes in leadership style (eg, the overall complex web of rules and policies across an organisation) need to be decluttered (Rae et al., 2018) if they are to know which “behaviour is expected, rewarded and supported” (Zohar, 2010). Leaders need to engage with their workers to clarify any changes.

See section 19 HSWA for the definition of a worker and section 45 for the duties that every worker has. Note that managers and team leaders are also workers and so have personal duties.

4.4.4 Leadership by OHS professionals and consultants

A consultant may also be a PCBU with a duty under section 36(2) to “ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, that the health and safety of other persons is not put at risk from work carried out as part of the conduct of the business or undertaking”.

Health and safety practitioners, professionals and consultants are also workers within the meaning of the HSWA and, while at work, must (HSWA section 45(b)) “take reasonable care that his or her actions do not adversely affect the health and safety of other persons”. The Act also requires “any individual” to take care of their own safety (section 47).

See Figure 37 for a suggested approach to who might be competent to carry out a risk assessment.

Several articles have been published about the duties owed by consultants in the UK (Bridges, 2015a, 2015b; Goldman & Lewis, 2008; Heatley, 2020) and New Zealand (Lloyd & Healy, 2017; Lund, O. & Aldridge, 2020).

During the public enquiry into the Grenfell Tower fire a fire risk assessor who carried out fire risk assessments between 2010 and 2017 admitted he had misrepresented his qualifications and experience (Knutt, 2021). Another fire risk assessor who provided an inadequate assessment for a residential block in Southampton was fined £2,750, ordered to pay costs of £19,952 and a given a three-month prison sentence suspended for 18 months (Lamy, 2021).

His Honour Roberts J, (WorkSafe NZ v Precision Animal Supplements Ltd, 2018a), commented in a case before the Ashburton District Court that:

The health and safety consultant engaged did not have the experience in health risk management or hazardous substances risk management.

In 2019 an apprentice worker was overcome by fumes while cleaning the engine of a boat. His employer, Aimex Ltd subsequently pleaded guilty to a section 36(2) charge and was convicted and fined (WorkSafe NZ v Aimex Ltd, 2021). Later a whistle-blower reported to WorkSafe that the health and safety manager and a director had concealed evidence of an earlier event and lied to WorkSafe. The Police investigated and charged both with obstruction (R v William Sullivan, 2023). A summary of the cases and subsequent appeals to the High Court (Houlston & Perkins, 2023) provides more details and a legal perspective.

In 2024 a firm of consultants was convicted for failure, as contracted, to devise a traffic management plan for a client (Worksafe New Zealand v Safe Business Solutions Ltd, 2024). As a result, a worker was hit by a moving vehicle and suffered serious injury.

Such behaviours are grossly unprofessional, with the potential to adversely affect the health and safety of other people, or to lead to death or serious injury or (as in the Ashburton case) serious illness. Such an outcome might be held to be reckless conduct (section 47, HSWA).

4.5 Identifying what’s missing in the management system

The purpose of a management system is to help a PCBU achieve its objectives or goals. For work health and safety identify a specific goal that is Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Timely – SMART (Bjerke & Renger, 2017). Mapping what is already in a management system and identifying what is missing will help develop an action plan for improvement. This can be done using Fishbone or Ishikawa analysis (section 21.3.12).

4.6 Chapter summary

This chapter provides only a high-level summary of some material relevant to leadership and engagement. The cited papers give access to more of the relevant research and grey literature that can be explored for a deeper understanding.

Research needs

Little of the leadership-related research relates to the New Zealand context. Our businesses and undertakings are often SMEs with (by international standards) few workers and few managers with “overseas experience”. How does the research relate to our economy?

Ebbevi et al. (2020) provided an analysis of the literature and suggested future research into “(1) which board activities influence OHS, (2) how board activities influence OHS, (3) the influence of context and (4) the leadership role of boards of directors”.

4.7 References used in this chapter

Barsh, J., Capossi, M., & Davidson, J. (2008). Leadership and Innovation. McKinsey Quarterly, 37-47.

Bell, N., Lekka, C., & Gervais, R. (2015). Case studies to demonstrate the practical application of the Leadership and Worker Involvement Toolkit (LWIT) [Research Report RR1067]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Bell, N., Sykes, P., & Powell, C. (2014, December). Give & Take. Safety & Health Practitioner, 39-41.

Bjerke, M. B., & Renger, R. (2017). Being smart about writing SMART objectives. Evaluation and Program Planning, 61, 125-127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.12.009

Boardman, J., & Lyon, A. (2006). Defining best practice in corporate occupational health and safety governance [Research Report RR0506]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Bridges, K. (2015a, March). Could that have been me? Safety & Health Practitioner.

Bridges, K. (2015b, February). Tough on the sentencing of health and safety crime. Safety & Health Practitioner, 33(2), 15.

Cohen, A. (1977). Factors in successful occupational-safety programs. Journal of Safety Research, 9(4), 168-178.

Cooper, D. (2014, September). Making an impact. Safety & Health Practitioner. www.shponline.co.uk

Dabee, N. (2020). How to Regulate the Due Diligence Duties of Officers under the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015. Victoria University of Wellington Law Review, 51(3), 379-412. https://doi.org/10.26686/vuwlr.v51i3.6609

Donovan, S.-L., Salmon, P. M., Horberry, T., et al. (2018, 2018/01/01/). Ending on a positive: Examining the role of safety leadership decisions, behaviours and actions in a safety critical situation. Applied Ergonomics, 66, 139-150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2017.08.006

Ebbevi, D., Von Thiele Schwarz, U., Hasson, H., et al. (2020). Boards of directors’ influences on occupational health and safety: a scoping review of evidence and best practices. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 14(1), 64-86. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijwhm-10-2019-0126

Flin, R., & Yule, S. (2004). Leadership for safety: industrial experience. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 13(suppl 2). https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2003.009555

Goldman, L., & Lewis, J. (2008). Whose duty? Occupational Health, 60(3), 14.

Heatley, A. (2020). UK HSE Successfully Prosecutes a Health and Safety Advisor for Deficient Advice. Lexology. Retrieved 15 July from https://www.lexology.com/

Houlston, S., & Perkins, B. (2023). Health and Safety: The Consequences of Dishonesty. Lexology. https://www.lexology.com/

ISO/IEC Annex SL. (2020). Proposals for management system standards. In Directives, Part 1: Consolidated ISO Supplement – Procedures specific to ISO (11th ed.). International Standards Organization. https://www.iso.org/directives-and-policies.html

King, K., Lunn, S., & Michaelis, C. (2010). Director Leadership Behaviour Research [Research Report RR0816]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Knutt, E. (2021). Grenfell fire risk assessor ‘misrepresented’ his qualifications and experience. https://www.ioshmagazine.com/2021/06/03/grenfell-fire-risk-assessor-misrepresented-his-qualifications-and-experience

Lamy, M. (2021). Suspended sentence for guilty fire risk assessor. https://www.ioshmagazine.com/2021/06/29/suspended-sentence-guilty-fire-risk-assessor

Lekka, C. (2013). A review of the literature on effective leadership behaviours for safety [Research Report RR0952]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Lloyd, A., & Healy, N. (2017). Consultants at risk. Safeguard, (162), 8.

Lund, O., & Aldridge, P. (2020, March/April). Stay in your lane. Safeguard, (180).

Macleod, D., & Clarke, N. (2009). Engaging for success: Enhancing performance through employee engagement [Report 859/07/09NP. URN09/1075]. Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, London. www.bis.gov.uk

Maritime NZ v Anthony Michael Gibson [2024] NZDC 27975 Auckland District Court.

Maritime NZ v Nino’s Ltd, Antonio Innocenzo Basile, Shane Michael McCauley [2020] NZDC 2536 Wellington Wellington District Court. https://www.districtcourts.govt.nz/

Mellor, N., Arnold, J., & Gelade, G. (2008). The effects of transformational leadership on employees’ absenteeism in four UK public sector organisations [Research Report RR0648]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Miller, M., & Shearn, P. (2005). Director Leadership of Health and Safety [Research Report HSL/2005/21]. Health and Safety Executive, Sheffield. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/hsl/

Molnar, M. M., Von Thiele Schwarz, U., Hellgren, J., et al. (2018, 2018/12/07/). Leading for safety: A question of leadership focus. Safety and Health at Work. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2018.12.001

O’Dea, A., & Flin, R. (2003). The role of managerial leadership in determining workplace safety outcomes [Research Report RR0044]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrhtm/index.htm

O’Neill, S., & Wolfe, K. (2014). Officers’ due diligence: Is work health and safety an accounting problem? J Health & Safety Research & Practice, 6(1), 15-21. https://www.aihs.org.au/news-and-publications/publications

Peace, C., Mabin, V., & Cordery, C. (2017). Due diligence: a panacea for health and safety risk governance? Policy and Practice in Health and Safety, 15(1), 19-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/14773996.2016.1275497

Peters, T., & Waterman, R. (1982). In Search of Excellence: lessons from America’s best-run companies. Harper & Row.

R v William Sullivan [2023] NZDC 15041 Nelson District Court. https://www.lexology.com/

Rae, A., Provan, D., Weber, D. E., et al. (2018). Safety clutter: the accumulation and persistence of ‘safety’ work that does not contribute to operational safety. Policy and Practice in Health and Safety, 16(2), 194-211. https://doi.org/10.1080/14773996.2018.1491147

Roberts, J., & Weatherall, M. (2024). Health and Safety obligations for officers – Maritime NZ v Tony Gibson.pdf. Lexology. https://www.lexology.com/

Smith, M. J., Cohen, H. H., Cohen, A., et al. (1978). Characteristics of Successful Safety Programs. Journal of Safety Research, 10(1), 5-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2013.07.050

von Thiele Schwarz, U., Hasson, H., & Tafvelin, S. (2016). Leadership training as an occupational health intervention: Improved safety and sustained productivity. Safety Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2015.07.020

WorkSafe NZ v Aimex Ltd [2021] NZDC 14313 Nelson District Court. https://www.districtcourts.govt.nz/

WorkSafe NZ v Andrew Buttle, James Buttle & Peter Buttle [2023] NZDC 18939 Auckland District Court.

WorkSafe NZ v Precision Animal Supplements Ltd [2018a] NZDC 19342 Ashburton District Court. https://www.districtcourts.govt.nz/

Worksafe NZ v Safe Business Solutions Ltd [2024] NZDC 19761 New Plymouth District Court.

Zohar, D. (2010). Thirty years of safety climate research: Reflections and future directions. Accident analysis and prevention, 42(5), 1517-1522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2009.12.019