5 High-level planning: objectives and key legislation

5.1 Chapter overview

Cross reference to ISO31000; ISO45001; Annex SL clause 6.1; and SafePlus (section 2.2.5).

Definitions of italicised terms are in the Glossary.

Check for key readings, webinars, interviews, and videos for complementary resources.

The following are some contemporary issues that may need to be considered:

- What is or will be the impact of artificial intelligence on the business?

- data management (Barker, 2020)

- support for the health (including mental health) of workers (Bell, Powell, et al., 2015; Brown-Haysom, 2020; Glass, 1992; Hodge & Bowler, 2023)

- fatigue (Jervis et al., 2023) and two District Court cases (2016-NZDC-16603-NZ-Police-v-Freightlines-Ltd.pdf, 2015) and (WorkSafe NZ v Michael Vining Contracting Ltd, 2018)

- development of virtual reality systems (Ahn et al., 2020; Forsyth, 2020; Leathley, 2019; Nilsson et al., 2020; Shafiq & Afzal, 2020)

- the future of office, remote and home working (Lund, S. et al., 2020; Where Now Consulting Ltd, 2020).

Relevant law

- Health and Safety at Work Act 2015

- Health and Safety at Work (Worker Engagement, Participation, and Representation) Regulations 2016

- Health and Safety at Work (General Risk and Workplace Management) Regulations 2016

Key questions

If risk is the “effect of uncertainty on objectives”:

- what are the high-level objectives of the organisation, PCBU, activity, system, or item?

- what are the uncertainties about achieving the objectives?

- how do or will those uncertainties affect achievement of those objectives?

- how can those high-level objectives be achieved by a systematic, high-level planning?

Useful management techniques

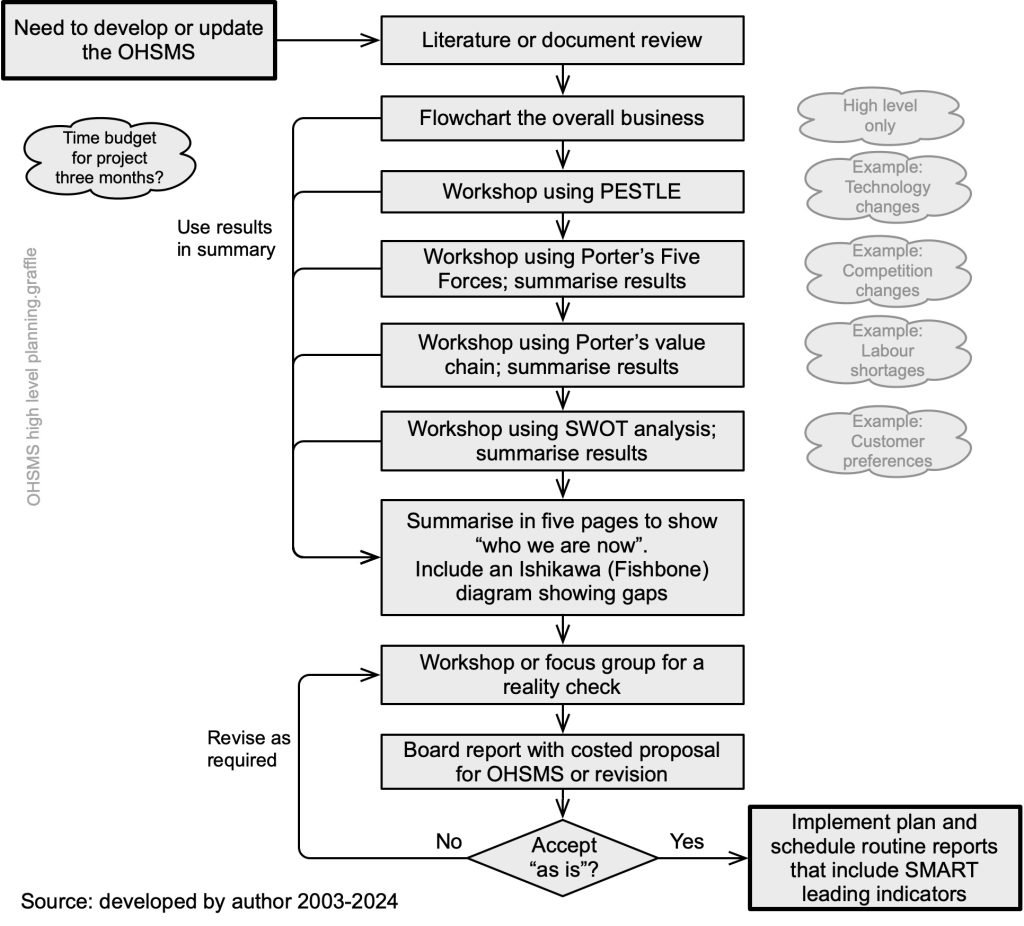

Use of the following techniques may help research to establish high-level plans for OHS (see also Figure 12).

- Flowcharting or process mapping to help understand how the overall process works (section 21.3.13)

- Fishbone or Ishikawa analysis (section 21.3.12)

- Focus groups to help discover the needs and expectations of workers and other stakeholders (section 21.3.14)

- Literature or document review, including legislation, to further help understand what the PCBU does or is required to do (section 21.3.22)

- PESTLE analysis to help understand the “big picture” of the whole PCBU (section 21.3.27)

- Porter’s Five Forces to help understand how market forces shape the PCBU (section 21.3.28)

- Porter’s Value Chain (section 21.3.29) to help understand relationships within the PCBU and with other PCBUs sharing the same duty Health and Safety at Work Act 2015, section 34

- SWOT analysis to help understand the strengths and weaknesses of the PCBU, and the opportunities it has and the threats it is exposed to (section 21.3.39).

See Figure 2 in the preface containing links between the risk management process and high-level planning.

5.2 Objectives and planning to achieve them

At this stage it will be important to identify the high-level objectives for occupational health and safety. Objective is defined by ISO as the “result to be achieved” (ISO/IEC Annex SL, 2020). Other terms, including goal, can be used to indicate what an organisation (here, a PCBU) exists to do or deliver. In the private sector objectives will include making a profit, but might include customer service or corporate social responsibility, a catchall term that incorporates OHS, quality and environmental management.

High-level objectives are set by the board or its equivalent and chief executive with the active support of the leadership team. It is often found that the objectives have been set with no planning for how they will be achieved because the key activities have not been the subject of a risk assessment – an enquiry into how the PCBU operates and the uncertainties about achieving its objectives.

5.2.1 Objectives generally

Objective defined

This subsection is from Peace (2019).

Objective is the goal or aim (Oxford University Press Ltd, 2022), or the “result to be achieved” although words with a “similar meaning (eg, aim, goal or target)” (ISO/IEC Annex SL, 2012, p. 144) can also be used. While goals or objectives may be set at an organisational level, they can have different aspects such as financial, health and safety, and environmental goals, and can apply at different levels such as strategic, organisation-wide, project, product, and process. Dettmer (2011, p. 2) described “goal” as:

The ultimate purpose for which the system exists (or was created) – the end to which a system’s collective efforts are directed. In human systems or organizations, this is the outcome that the owners say is the preeminent or paramount objective of the system.

Knowing the organisational objectives or goals is key to planning, delivery of goods or services, and development of a shared organisational purpose (Dettmer, 2007; Drucker, 1973 p. 400). The overarching goal may be an abstract, high-level outcome but is achieved through a “system of interrelated activities” (Weick & Roberts, 1993, p. 364), representing “the sum of a significant number of functional tasks or activities” (Dettmer, 2011), including risk assessments. Moreover, “to ensure safety, it is common to use a hierarchy of goals …” (Aven et al., 2006, p. 119) or organisational objectives that are supported by subordinate goals, objectives, priorities or accountabilities for managers, workers, systems and activities. Management at all levels should be involved in setting such goals and objectives and guiding the organisation to their achievement (Aven et al., 2006). This was described by Drucker (1954) as management by objectives.

Vandewalle, Nerstad, & Dysvik (2019) reviewed 40 years of goal orientation and showed that orientation away from performance goals and towards learning goals resulted in skills gains, improved decision making in complex situations, improved cognitive strategies (including using diagrams and charts), greater willingness to seek or accept feedback, and more ethical behaviours.

Reviewing 35 years of research into goal-setting, Locke & Latham (2002, p. 714) concluded that “goal-setting theory is among the most valid and practical theories of employee motivation in organisational psychology” and that goal-setting works at the organisational and individual levels. They identified four performance mechanisms affected by goals, including that goals direct attention to relevant activities and away from irrelevant activities. Provided workers have necessary resources and training, task-relevant knowledge and strategies can be applied to achievement of performance goals to “create constructive discontent with … present performance”. This can lead to self-improvement efforts that can be amplified by feedback during and on completion of tasks, resulting in a sense of accomplishment (Latham & Locke, 2006).

Guidance from ISO45001 (2018, p. 31, paragraph A.6.2.1)

Objectives are established to maintain and improve OHS performance. The objectives should be linked to risks and opportunities and performance criteria which the organization has identified as being necessary for the achievement of the intended outcomes of the OHS management system.

OHS objectives can be integrated with other business objectives and should be set at relevant functions and levels. Objectives can be strategic, tactical, or operational:

a) strategic objectives can be set to improve the overall performance of the OHS management system (eg, to eliminate noise at source);

b) tactical objectives can be set at facility, project, or process level (eg, to reduce noise at source);

c) operational objectives can be set at the activity level (eg, the enclosure of individual machines to reduce noise).

The measurement of OHS objectives can be qualitative or quantitative. Qualitative measures can be approximations, such as those obtained from surveys, interviews, and observations. The organisation is not required to establish OHS objectives for every risk and opportunity.

5.2.2 Planning to achieve OHS and other objectives

See Figure 2 of the preface, showing links between the risk management process and planning for high-level objectives.

Risk is defined in ISO31000 as the “effect of uncertainty on objectives”. When planning at a high level we need to know what the business objectives are that have been signed off by the board or equivalent and can then explore how they are intended to be achieved. This will help show where there are uncertainties about the health or safety of workers and other people. Planning requires knowledge of what is done and how it is carried out. These are found by an enquiring approach using structured techniques as suggested in Figure 12.

Description of the process for use of management techniques in high-level planning

The process for gathering information to enable high-level planning for implementation or updating an occupational health and safety management system (OHSMS) suggested in Figure 12 has an indicative time budget of three months. For a project of such a scale sign-off by the board or equivalent should be requested and a project governance framework established. The OHS professional may need support from others familiar with the PCBU at different stages. They may need to visit each site or activity and meet with local leaders and health and safety representatives.

The literature or document review should identify the key legislation, policies and other relevant documents that influence, or should influence, the OHSMS. Arising from this work one or more high-level flowcharts can be developed onto which key OHS-related information can be mapped. The flowcharts should be reviewed in a workshop to ensure they are a fair representation of activities, and any deficiencies remedied.

A series of one-hour workshops using PESTLE analysis, Porter’s Five Forces, Porter’s Value Chain, and SWOT analysis will elicit further information about how the PCBU operates generally and in relation to OHS. The results of these workshops are written up in a summary report that includes flowcharts or other graphics. Use a Fishbone or Ishikawa analysis (section 21.3.12) to help summarise the results and show gaps. Write a formal board report requesting approval for the proposed development or revision of the OHSMS.

Sometimes a PCBU may operate in dynamic circumstances or anticipate rapid change. If so, it may be necessary to carry out a simple scenario analysis (section 21.3.37) to try to anticipate circumstances in 5-10 years. The results should be checked in a workshop with knowledgeable managers and workers. Such a scenario analysis may help shape, for example, changes in management style such as a move to “Safety II” and changes in information, training, instruction, or supervision.

For further guidance on what the OHSMS might need to include read and make notes annex A in ISO45001 (2018, pp. 32-33). Hosking (2018) suggested how a policy (the “intentions and direction of an organisation as formally expressed by its top management”) might be set out. Remember to declutter and aim to achieve an integrated management system (Peace, 2024a).

5.3 Tracking progress with high-level OHS objectives

Once an event has occurred the consequences can range from a near-hit to catastrophic. Such consequences may be rare. Instead of monitoring failures using lagging indicators OHS professionals should monitor the success factors – leading indicators – that drive improvements (Gaddis, 2019). This suggests using a goal tree (section 21.3.15) to help identify the critical success factors and their necessary conditions to identify leading indicators for success. Alternatively, the MORT chart and manual (section 21.3.24) shows factors that can be converted to leading indicators. Any leading indicators will probably be specific to a PCBU but should always be SMART (Bjerke & Renger, 2017):

- Specific

- Measurable

- Achievable

- Realistic

- Timely.

SMART leading indicators may take time to develop, requiring consultation with frontline workers and managers, as well as senior managers and officers. They may rely on surveys, inspections, or observations (section 21.3.18) and could use checklists (section 9.3.3). Leading indicators can be set for individual units in a PCBU or for the whole PCBU and should form part of due diligence and governance reporting.

Chosen indicators will need a range capable of showing bands of achievement. For example,

- 0-20% achieved

- 21-40% achieved

- 41-60% achieved

- 61-80% achieved

- 81-100% achieved

5.4 High-level planning: OHS legislation and common law origins

Much of our current OHS legislation is derived from English common law, Judge-made law, that has evolved since the 1850s. To understand some of our current statutes (legislation made by Parliament) and Regulations (subordinate legislation made by virtue of a statute but approved by Parliament) we need to understand the common law.

A tort is a wrongful act or an infringement of a duty of care. It includes breach of the common law which allows various forms of legal action for damages: for example, negligence, breach of statutory duty, libel. The tort of negligence in English common law has four elements, or requirements, namely (summarised and adapted from Bennett, D., 2019; Wilby, 2019):

1 The existence in law of a duty of care

There must be a situation in which the law attaches liability for carelessness.

Negligence is the omission to do something which a reasonable man, guided upon those considerations which ordinarily regulate the conduct of human affairs, would do, or doing something which a prudent and reasonable man would not do

In Blyth v Birmingham Waterworks Co (1856) 11 Exch 781 at 784 it was decided the duty of the employer is to guard against risks and prevent exposure of the employee to risks which the employer knows of or ought to have known about. A failure to take measures to protect against a risk of which no-one was, or could have been, aware, cannot amount to negligence. Very few risks fall within this category, but an earlier investigation that suggests a problem should have put an employer on notice of the need to take action.

There must be proximity between the defendant and the person who suffered harm; this may consist of various forms of closeness (physical, circumstantial, causative, or assumed).

2 Breach of the duty of care by the defendant

3 A causal or causative connection between the defendant’s careless conduct and the damage

4 The particular kind of damage to the particular claimant is attributable because it is not so unreasonable as to be too remote

There is a continuing requirement of reasonable foresight that harm, of the kind which in fact occurred, that might include the claimant.

The defendant need not subjectively foresee harm to the person injured; it is sufficient that they ought reasonably to foresee harm to a class of persons, that being knowledge that someone in the defendant’s position would be expected to possess. The greater the awareness of the potential for harm, the more likely it is that this criterion will be satisfied.

A duty of care will only arise if it is fair, just, and reasonable to impose one in novel circumstances. An employer should be aware of reasonably available information about the reasonably practicable precautions to control a risk.

Reasonably practicable” is a narrower term than “physically possible” and it seems to me to imply that a computation must be made by the owner, in which the quantum of risk is placed on one scale and the sacrifice involved in the measures necessary for averting the risk (whether in money, time or trouble) is placed in the other; and that if it be shown that there is a gross disproportion between them – the risk being insignificant in relation to the sacrifice – the defendants discharge the onus on them. Moreover, this computation falls to be made by the owner at a point of time anterior to the accident. (Asquith LJ., 1949 in Edwards v NCB)

This is the basis of the definition of reasonably practicable in section 22 HSWA.

5.4.1 The Robens report: The start of the era of modern OHS legislation

As noted, the origins of the British Health and Safety at Work Act (1974) were in the 19th century (Brabant, 2024) and led to the appointment of the Robens Committee and its report (Lord Robens et al., 1972) published on 9 June 1972 with the preamble:

“We were appointed on 29th May 1970 by the Right Honourable Barbara Castle, M.P., then Secretary of State for Employment and Productivity, as a Committee of Inquiry with the following terms of reference:

To review the provision made for the safety and health of persons in the course of their employment (other than transport workers while directly engaged on transport operations and who are covered by other provisions) and to consider whether any changes are needed in:

(1) the scope or nature of the major relevant enactments, or

(2) the nature and extent of voluntary action concerned with these matters,

And to consider whether any further steps are required to safeguard members of the public from hazards, other than general environmental pollution, arising in connection with activities in industrial and commercial premises and construction sites, and to make recommendations”.

The brief of the Committee was not drawn from an industrial disaster but from realisation that UK legislation was out of date and not fit for the last quarter of the 20th century. Some of its major findings follow.

- 1,000 deaths per year is a fatal injury rate of 4.5 per 100,000 (this is about the same as New Zealand in the decade 2005-2014, 40 years after the Robens report was published).

- “The first and perhaps most fundamental defect of the statutory system is simply that there is too much law … The primary responsibility for doing something about the present levels of occupational accidents and disease lies with those who create the risks and those who work with them (pp 6-7)”.

- “The most fundamental conclusion to which our investigations have led us is this. There are severe practical limits on the extent to which progressively better standards of safety and health at work can be brought about through negative regulation by external agencies. We need a more effectively self-regulating system” (P12).

- “Promotion of safety and health at work is an essential function of good management. We are not talking here about legal responsibilities. The job of a director or senior manager is to manage. The boardroom has the influence, power, and resources to take initiatives and to set the pattern” (P14-15)

- “54. Whilst safety and health must be the direct operational responsibility of line management, we are equally clear that there is an important role for the specialist safety adviser or safety officer, standing in the same relationship to line management as do other specialists such as personnel officers”.

- “It is generally accepted that there is no credible way of measuring the value of consultative and participatory arrangements in terms of their direct effect upon day-to-day safety performance. Nevertheless, most of the employers, inspectors, trade unionists and others with whom we discussed the subject are in no doubt about the importance of bringing workpeople more directly into the actual work of self-inspection and self-regulation by the individual firm. There is no real dispute about these aims” (P.21).

- “We recommend therefore, that the directors’ reports lodged with the Registrar of Companies should be required to include prescribed information, including statistics, about reportable accidents and industrial diseases suffered by the company’s employees and about measures taken by the company in this regard” (P.26).

- A new Act “… should spell out the basic duty of an employer to provide a safe working system including safe premises, a safe working environment, safe equipment, trained and competent personnel, and adequate instruction and supervision. It should also spell out the duty of an employee to observe safety and health provisions and to act with due care for himself and others” (P.41).

- “397. Generally speaking, there has been no shortage of scientific research into physical and medical aspects of occupational safety and health problems. More knowledge is needed, however, about the influence of human and organisational factors in accident causation, about the interaction of multiple causative factors in actual work situations, and about the effectiveness of preventive measures”.

The Robens Committee was appointed by a UK Labour Government but its report was so well researched and had such wide support that the subsequent Health and Safety at Work Bill was enacted in 1974 under a Conservative Government. Fifty years later the British Act remained substantially as originally passed. See section 2.2.3 for further comment on the common law and management of a business.

5.5 New Zealand Health and Safety at Work Act 2015

The New Zealand Health and Safety at Work Act (2015) was adapted from the Australian Model Work Health and Safety Bill (2011) which was, in turn, adapted from the British Health and Safety at Work Act (1974). The UK Act was the result of the work of the Robens Committee (Lord Robens et al., 1972) which drew on about 150 years of UK common law. New Zealand legislation is, therefore, derived from nearly 200 years consideration in the UK and Australia of the duty of care owed by employers to their workers.

Introduction of the ACC scheme in New Zealand following the Woodhouse Report (1967) removed the common law right to sue for negligence, arguably removing a driver for effective management of occupational health and safety (Peace, 2008) and contributing to the slower development of a national culture for health and safety (Peace et al., 2019).

Person conducting a business or undertaking

“Contractorisation” has resulted in many large organisations using a wide range of contractors instead of permanent employees. Franchises and “on-call” workers in the informal or gig economy have also altered employment relationships. Introduction of the term “person conducting a business or undertaking” (PCBU) in the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 acknowledged the major changes in employment relationships that had occurred since 1990. The word “person” can be applied to human being or to a business or undertaking that is, legally, a person.

PCBU is a wider term than “employer” and “principal” and covers any size or type of organisation or self-employed person unless specifically excluded.

At this point you should read and make notes about the meaning of the term PCBU in HSWA section 17.

Workplace

A High Court case (Murray Kelvyn Sarginson v CAA, 2020) confirmed that people engaged in an activity ‘arising from work’, will be ‘at work’ for the purposes of the HSWA, regardless of where they were.

5.5.1 Duty of care

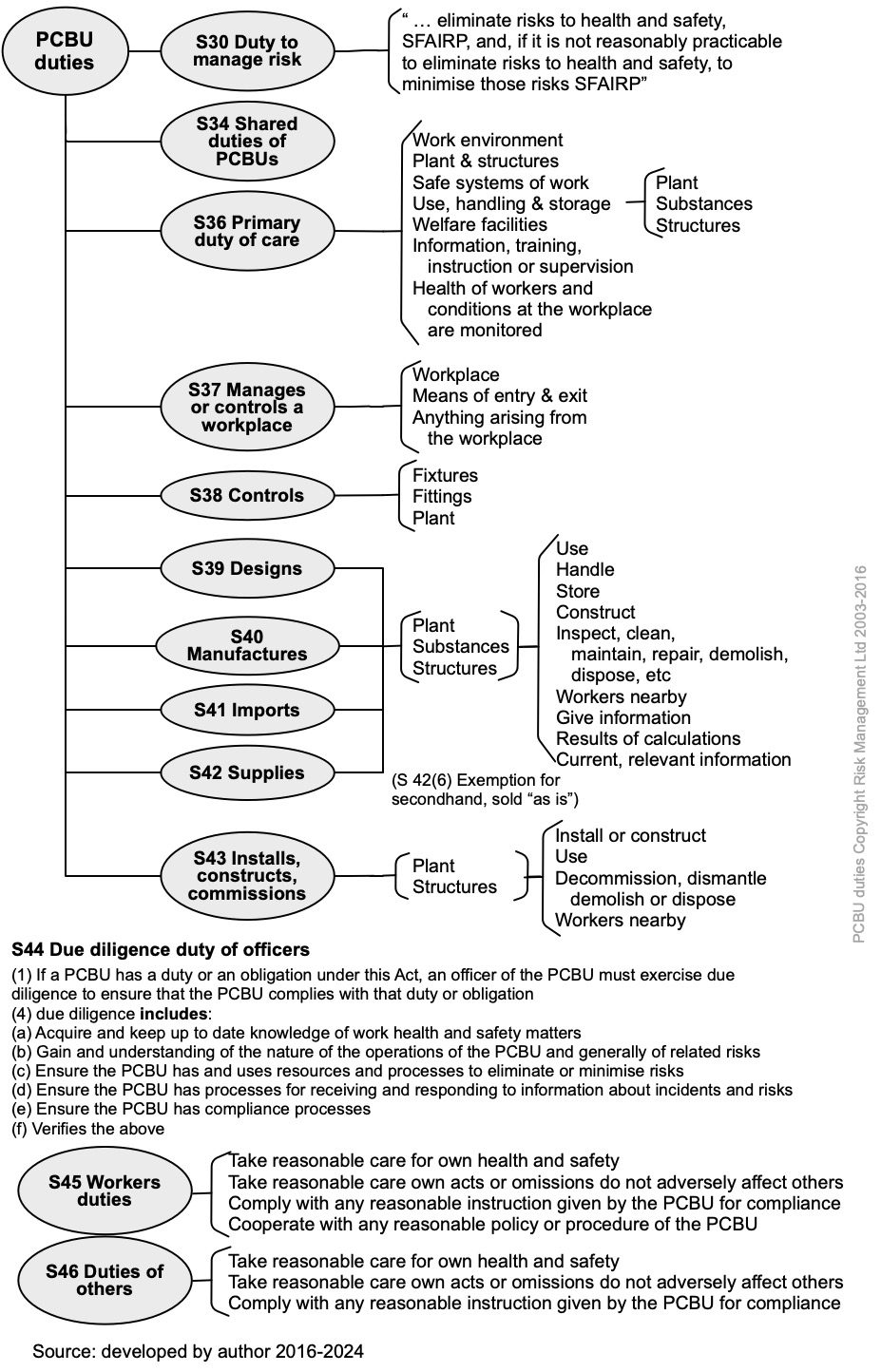

Read and make notes about HSWA section 30 which sets out the overarching general duty of a PCBU to eliminate risks to health and safety, or, if that is not reasonably practicable, to minimise those risks.

Think widely about section 34 and read summary examples of a civil law case in Australia (Ball, 2022) and criminal case (Langusch, 2023).

Read and make notes about sections 36-46 which set out duties owed by PCBUs, and by officers, workers, and other people in workplaces. Note that section 36(3) sub-sections b, c and d do not mention “health”. Is this a deliberate gap? Is it covered by the general requirement of section 36(1)? The duties are summarised in Figure 13. Also read and make notes about the General Regulations (HSWGR, 2016) to get a fuller understanding of the legal requirements.

5.5.2 Due diligence, officers, and directors

See section 4.4.1 above and Ebbevi et al. (2020), Peace et al. (2017) and (Maritime NZ v Anthony Michael Gibson, 2024). The due diligence obligations in section 44, HSWA, and similar provisions in section 137, Companies Act, are set out in the following table. Read and make notes on the law so that you can focus reports to officers on their legal obligations.

Table 4. Comparison of officers’ and directors’ duties and powers

|

Health and Safety at Work Act definitions and obligations |

Companies Act definitions and obligations |

|---|---|

| Section 18, Meaning of officer | Section 126, Meaning of director |

| Section 44, Duty of officers | Section 137, Director’s duty of care |

| There is no equivalent of section 138, Companies Act in HSWA. However, it might be reasonable to use section 138(1) as guidance on how an officer might rely on “reports, statements, and … data and other information prepared or supplied, and on professional or expert advice given” to them. Section 138(2) of the Companies Act should form part of how an officer uses such reports, etc. | Section 138, Use of information and advice |

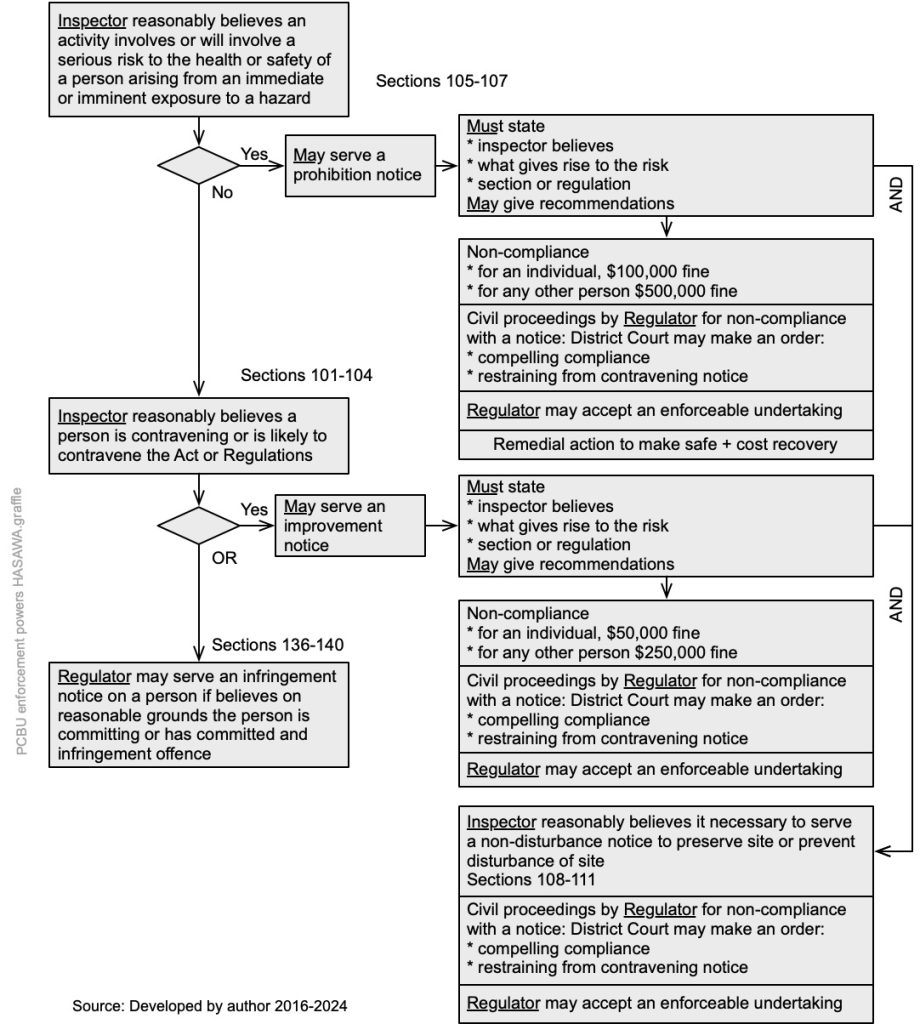

5.5.3 Enforcement powers in HSWA summarised

Figure 14 summarises the enforcement powers of an inspector or the regulator. Note there are differences between who may act (an inspector or the regulator).

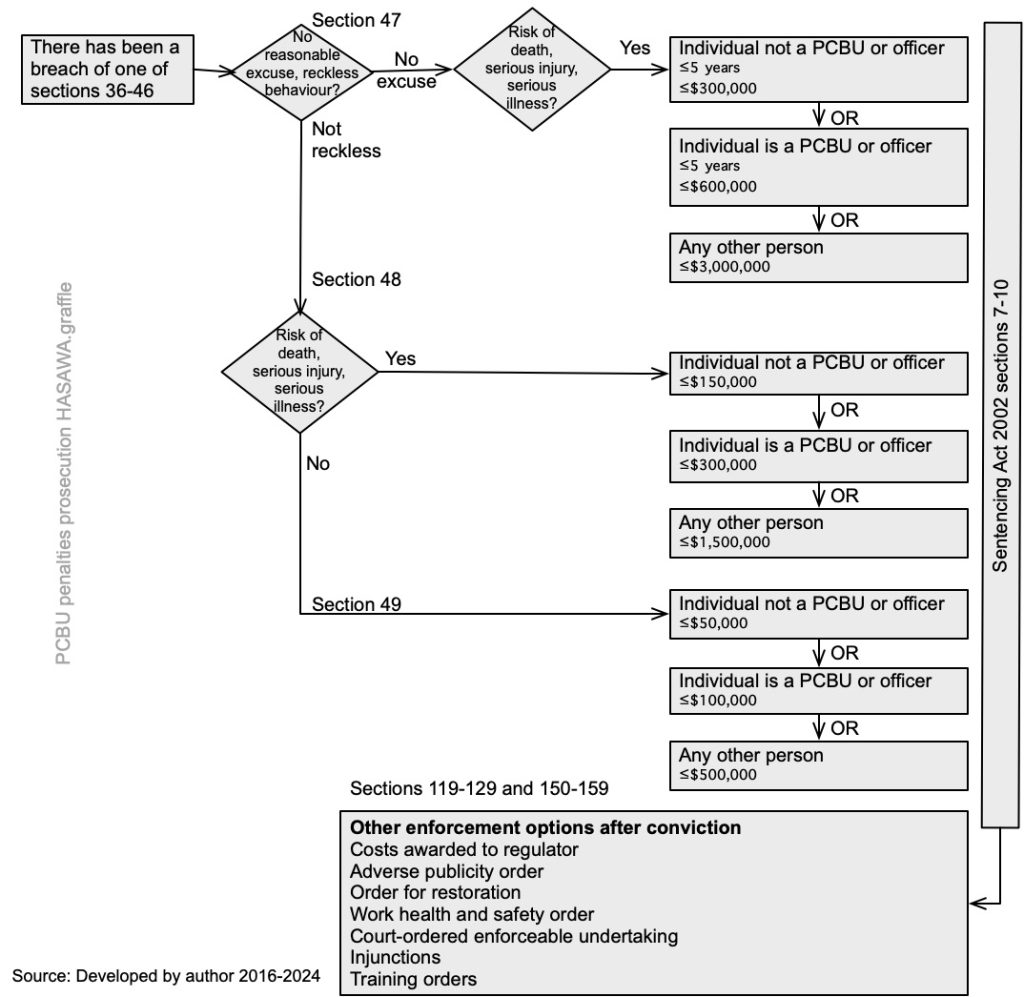

5.5.4 Penalties under HSWA summarised

Figure 15 summarises penalties under HSWA for a breach of sections 36-46.

5.6 Chapter summary

This chapter has shown a high-level approach to planning or revising how an OHSMS operates in a PCBU. To avoid duplication of documented procedures it is most important that the OHSMS is fully integrated with other management systems (Peace, 2024a). The suggested approach may also contribute to medium- or long-term improvements in management across the PCBU.

The origins of current New Zealand occupational health and safety statute law has been summarised, showing it is based on more than 170 years legal history and case law that has moved with changes in society and technology. A few District Court decisions of interest since 2016 (when the Act came into force) are mentioned.

5.7 References used in this chapter

Bennett, D. (2019). The development of employer’s liability law. In D. Bennett (Ed.), Munkman on Employer’s Liability (17th ed., pp. 1-32). Lexis Nexis.

Bjerke, M. B., & Renger, R. (2017). Being smart about writing SMART objectives. Evaluation and Program Planning, 61, 125-127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.12.009

Brabant, D. (2024). Health and Safety Law from the Industrial Revolution to the New Zealand Health and Safety at Work Act 2015. NZ Journal of Health and Safety Practice, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.26686/nzjhsp.v1i2.9546

Brown-Haysom, J. (2020). Strength in support. Safeguard, 24-26.

Dettmer, H. W. (2007). The logical thinking process: a systems approach to complex problem solving. American Society for Quality.

Dettmer, H. W. (2011). Our goal is … What is our goal? [Research paper]. Goal Systems International, http://goalsys.com/

Drucker, P. (1954). The practice of management. Harper & Row.

Drucker, P. (1973). Management: tasks, responsibilities, practices. Harper & Row.

Ebbevi, D., Von Thiele Schwarz, U., Hasson, H., et al. (2020). Boards of directors’ influences on occupational health and safety: a scoping review of evidence and best practices. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 14(1), 64-86. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijwhm-10-2019-0126

Forsyth, S. (2020). Confined animations. Safeguard, 61.

Gaddis, S. (2019). Seven leading indicators to drive safety improvement in your organization [Report]. Intelex Technologies ULC, Toronto. https://www.intelex.com/

Glass, W. (1992). The Occupational Health Audit: An Organization’s Barometer? Managerial Auditing Journal, 7(6), 13-16. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb017603

Health and Safety at Work Act (2015). New Zealand http://www.legislation.govt.nz/

Health and Safety at Work etc Act (1974). Great Britain http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1974/37

Hodge, K., & Bowler, S. (2023). It Is a Cultural Thing: Can Employers Be Held Liable for a Poor Workplace Culture? Lexology. https://www.lexology.com/

Hosking, L. (2018, March). Foundation documents: policy writing. IOSH Magazine.

HSWGR (2016), Health and Safety at Work (General Risk and Workplace Management) Regulations. New Zealand. http://www.legislation.govt.nz/

ISO/IEC Annex SL: 2012 Directives, Part 1. Consolidated ISO Supplement – Procedures specific to ISO, International Standards Organization, Geneva. https://www.iso.org/directives-and-policies.html

ISO/IEC Annex SL. (2020). Proposals for management system standards. In Directives, Part 1: Consolidated ISO Supplement – Procedures specific to ISO (11th ed.). International Standards Organization. https://www.iso.org/directives-and-policies.html

Jervis, K., Richardson, E., & Irwin-Faulks, N. (2023). Don’t hit the snooze button! It’s time for organisations to wake up to fatigue management. Lexology. https://www.lexology.com/

Langusch, J. (2023, 30 June). Legal employer, but not liable employer? Lexology. https://www.lexology.com/

Latham, G. P., & Locke, E. A. (2006). Enhancing the Benefits and Overcoming the Pitfalls of Goal Setting. Organizational Dynamics, 35(4), 332-340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2006.08.008

Leathley, B. (2019). Feeling the heat? IOSH Magazine, (December), 32-36.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a Practically Useful Theory of Goal Setting and Task Motivation. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705-717. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.57.9.705

Lord Robens, A., Beeby, G., Pike, M., et al. (1972). Safety and Health at Work: Report of the Committee, 1970-72 [Report Cmnd 5034]. HMSO, London. http://www.mineaccidents.com.au/uploads/robens-report-original.pdf

Lund, S., Madgavkar, A., Manyika, J., et al. (2020). What’s next for remote work: An analysis of 2,000 tasks, 800 jobs, and nine countries [Research Report MGI 2020]. McKinsey Global Institute, www.mckinsey.com

Maritime NZ v Anthony Michael Gibson [2024] NZDC 27975 Auckland District Court.

Model Work Health and Safety Bill (2011). Australia http://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/

Murray Kelvyn Sarginson v CAA [2020] NZHC 3199 Invercargill High Court. https://www.lexology.com/

Nilsson, T., Roper, T., Shaw, E., et al. (2020). Immersive virtual worlds: Multi-sensory virtual environments for health and safety training [Research Report ps0945]. Institution of Occupational Safety and Health, Leicester. https://iosh.com/

NZ Police v Freightlines Ltd [2015] NZDC 16603 Christchurch District Court. https://www.districtcourts.govt.nz/

Concise Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press Ltd. (2022).

Peace, C. (2008). A fresh approach to compensation. Safety & Health Practitioner, 26(5), 50-54.

Peace, C. (2019). The effectiveness of risk assessments in informing decision makers [PhD thesis, Victoria University of Wellington]. New Zealand. https://www.wgtn.ac.nz/library

Peace, C. (2024a). Integrating management systems in the energy sector: the case of the electricity industry in New Zealand. NZ Journal of Health and Safety Practice, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.26686/nzjhsp.v1i1.8680

Peace, C., Lamm, F., Dearsly, G., et al. (2019). The evolution of the OHS profession in New Zealand. Safety Science, 120, 254-262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2019.07.005

Peace, C., Mabin, V., & Cordery, C. (2017). Due diligence: a panacea for health and safety risk governance? Policy and Practice in Health and Safety, 15(1), 19-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/14773996.2016.1275497

Shafiq, M. T., & Afzal, M. (2020). Potential of Virtual Design Construction Technologies to Improve Job-Site Safety in Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Sustainability, 12(9), 3826. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093826

Vandewalle, D., Nerstad, C. G. L., & Dysvik, A. (2019). Goal Orientation: A Review of the Miles Traveled and the Miles to Go. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 6(1), 115-144. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062547

Weick, K. E., & Roberts, K. H. (1993). Collective Mind in Organizations: Heedful Interrelating on Flight Decks. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38(3), 357-381. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393372

Where Now Consulting Ltd. (2020). The future of the office and office workers [Research Report BCFA 2020]. Author, www.thebcfa.com

Wilby, D. (2019). The general principles of negligence. In D. Bennett (Ed.), Munkman on Employer’s Liability (17th ed., pp. 33-81). Lexis Nexis.

Woodhouse, O., Bockett, H., & Parsons, G. (1967). Compensation for Personal Injury New Zealand. Government printer, Wellington. http://www.library.auckland.ac.nz/data/woodhouse/

WorkSafe NZ v Michael Vining Contracting Ltd [2018] NZDC 6971 Huntly District Court. https://www.districtcourts.govt.nz/