2 Characteristics of successful safety programmes

2.1 Chapter overview

Cross reference to ISO45001, ISO31000; Annex SL clauses 6.1 and 8.1.

Definitions of italicised terms are in the Glossary.

Check for key readings, webinars, interviews, and videos for complementary resources.

Relevant law

- Health and Safety at Work Act 2015

- Health and Safety at Work (Worker Engagement, Participation, and Representation) Regulations 2016

- Health and Safety at Work (General Risk and Workplace Management) Regulations 2016

- Health and Safety at Work (Major Hazard Facilities) Regulations 2016

Key questions

What is or will be the impact of artificial intelligence on the business?

If risk is the “effect of uncertainty on objectives” (ISO31000: 2018):

- what are the objectives of the organisation, PCBU, activity, system, or item?

- what are the uncertainties about achieving the objectives?

- how do or will those uncertainties affect achievement of those objectives?

- how can those objectives be achieved by a systematic, management approach?

2.2 Introduction – development of safety management

Early research suggested that successful safety programmes included (Cohen, 1977):

Strong management commitment to safety as defined by various actions reflecting management’s support and involvement in safety activities.

Close contact and interaction between workers, supervisors, and management enabling open communications on safety as well as other job-related matters.

A workforce subject to less turnover, including a large core of married, older workers with significant lengths of service in their jobs.

A high level of housekeeping, orderly workplace conditions, and effective environmental quality control.

Well-developed selection, job placement, and advancement procedures plus other employee support services.

Training practices emphasizing early indoctrination and follow-up instruction in job safety procedures.

Evidence of added features or variations in conventional safety practices serving to enhance their effectiveness.

This research was based on a sample of businesses in Wisconsin more than 50 years ago (Cohen et al., 1975) and some of the success factors may no longer be relevant. However, as shown by Cohen, management commitment to safety and engagement with workers remain critical factors that help to manage “people” variables. Bornstein & Hart (2010) similarly found a successful OHSMS would have:

- senior management commitment

- worker participation

- proactive, rather than reactive, risk management

- integration of the OHSMS with other management systems

- long-term focus on targets other than occupational safety

- broadly based monitoring processes rather than narrow auditing focused on short-term, easily counted outcomes.

The International Labour Organisation published the occupational health services convention (ILO C155, 1981). The convention lists the following 11 multidisciplinary basic occupational health and safety functions that might be provided by an employer.

(a) identification and assessment of the risks from health hazards in the workplace;

(b) surveillance of the factors in the working environment and working practices which may affect workers’ health, including sanitary installations, canteens and housing where these facilities are provided by the employer;

(c) advice on planning and organisation of work, including the design of workplaces, on the choice, maintenance and condition of machinery and other equipment and on substances used in work;

(d) participation in the development of programmes for the improvement of working practices as well as testing and evaluation of health aspects of new equipment;

(e) advice on occupational health, safety and hygiene and on ergonomics and individual and collective protective equipment;

(f) surveillance of workers’ health in relation to work;

(g) promoting the adaptation of work to the worker;

(h) contribution to measures of vocational rehabilitation;

(i) collaboration in providing information, training and education in the fields of occupational health and hygiene and ergonomics;

(j) organising of first aid and emergency treatment;

(k) participation in analysis of occupational accidents and occupational diseases.

Where relevant to the control of workplace health hazards the functions could be incorporated in an OHSMS. They are closely aligned with the guidance set out in ISO45001 (2018) and ACC is proposing support for an accredited employer that wishes to use ISO45001.

Five basic characteristics of any OHSMS were identified as (Zwetsloot & Kuhl, 2013):

(1) It includes all components of OSH that are relevant to the members of the organisation and the business process.

(2) In principle, its functions are: (1) to increase the effectiveness of OSH management; (2) to guarantee compliance with existing legislation; and (3) to improve OSH performance. The OSH MS objectives are to be defined by the organisation and may include ethical, economic, legal and organisational goals. Not all OSH MS have similar objectives.

(3) It is a holistic approach, specifying and requiring implementation of a series of elements and (positive) interactions between them.

(4) It has provisions for system maintenance and continuity. The functioning of an OHS MS is evaluated on a regular basis (through OSH audits). A periodic review of its objectives and effectiveness is necessary to ensure continuous improvement.

(5) Its outputs (OSH performance) are important to the evaluation of the management system.

The third point suggests the need to take account of the interdependency characteristics of the OHSMS.

Effectiveness of OHSMS

Robson et al. (2007) carried out a systematic review of the effectiveness of voluntary and mandatory OHSMS interventions and defined an occupational health and safety management system as follows.

An OHSMS is the integrated set of organizational elements involved in the continuous cycle of planning, implementation, evaluation, and continual improvement, directed toward the abatement of occupational hazards in the workplace. Such elements include, but are not limited to, an organizations’ OHS relevant policies, goals and objectives, decision-making structures and practices, technical resources, accountability structures and practices, communication practices, hazard identification practices, training practices, hazard controls, quality assurance practices, evaluation practices, and organizational learning practices.

This might have a natural appeal to any regulator or advocate for safety management systems. Implementing an OHSMS will surely provide positive results that are measurable and reproducible. Can such evidence be found in the literature?

There is continuing debate in the research literature on OHSMS about whether, or at least to what extent, they actually produce real improvements in occupational health and safety outcomes in workplaces (Bornstein & Hart, 2010). Bornstein & Hart noted that some research shows:

- “off-the-shelf” voluntary management systems may not fit specific workplaces

- “off-the-shelf” systems produce apparently impressive results that are not supported by detailed analysis (an issue identified by other researchers)

- conventional auditing systems tend to look for predefined “programmes, policies and barriers” rather than questioning if the OHSMS is adequate in design and assumptions

- some OHSMS produce a façade of self-regulation and a reduction in employee involvement.

The reasons for establishment of an ISO management system may be other than to improve OHS performance (Fernández-Muñiz et al., 2012), including “whitewashing” to disguise performance failures.

Walker & Tait (2004) found improvements in safety management in 24 SMEs that volunteered to be part of their study. However, they believed many of the components of each OHSMS were already in place before the study and the intervention worked mainly to bring them together in a system. Was this evidence for the “interdependency characteristic of systems”?

A review of the effectiveness of OHSMS in securing healthy and safe workplaces by Gallagher, Underhill, & Rimmer (2001) for the Australian National Occupational Health and Safety Advisory Committee (NOHSAC) found no conclusive evidence in favour of OHSMS. They noted that methods for evaluation of an OHSMS need to take account of the following:

- method of establishment (voluntary or mandatory)

- principle OHS control strategy (safe person/safe place)

- management structure and style (innovative or traditional)

- level of system development (meeting basic specifications or stakeholder needs)

- degree of implementation (introductory or fully operational).

Gallagher et al. (2001) concluded there were three barriers to successful implementation of any OHSMS:

- system design faults, including failure to consult with employees, and lack of integration with general management functions and systems

- inappropriate use of audit tools which can induce system design faults

- contextual constraints on OHSMS often exist in sections of a business or workforce where implementation encounters special difficulties.

Robson et al. (2007) found seven systematic studies of voluntary OHSMS, one showing no improvements and six with some improvements. However, they had reservations about methodologies in all but one of the studies. Two key concerns were:

- bias on the part of the authors as some appeared to be advocates of OHSMS implementation

- bias on the part of organisations participating in the studies as they volunteered and may have had a bias towards success.

Their studies of nine mandatory OHSMS showed improvements in OHS indicators but there were reservations about the studies, and they concluded that:

… despite the generally positive results on the effectiveness of OHSMS interventions in the published, peer-reviewed literature, the evidence is insufficient to make recommendations either in favour of or against particular OHSMSs. This is not to judge these systems as ineffective or undesirable; it is merely to say that it would be incautious to judge either way in the present state of our research knowledge.

Rocha (2010) considered institutional effects on OHSMS. As part of his article, work by others was reviewed showing conflicting arguments for and against OHSMS, summarised in Table 2.

Table 2. Arguments for and against OHSMS

|

Arguments for OHSMS |

Arguments against OHSMS |

|---|---|

| OHSMS have a significant impact in reducing both direct health care costs and absenteeism | OHSMS do not support creativity and experiment which are crucial for organisational learning |

| Organisations use OHSMS as a “searching map” to help improve health and safety and solve internal problems | An OHSMS can mask problems by directing resources to system maintenance rather than problem solving |

| In periods of low unemployment, more educated employees seek out employers who match expectations for managing work environment issues | Firms seek to emulate successful competitors without fully understanding cause, effect, and culture |

Rocha (2010) also made the point that successful introduction of OHSMS into organisations is highly dependent on the institutional environment of the country. Failure to recognise such differences may result in the “law of unintended consequences” producing unexpected outcomes from an apparently good proposal.

… firms in different countries have distinct possibilities to deal with the requirements of OHSMS, which in turn demands distinct institutional enforcement regimes for OHS: For instance, institutional mechanisms which compensate for the weak abilities of workers to interfere in OHS issues must be established. (p. 222)

That is, the consultation and collaboration arrangements within a country need to be conducive to effective engagement with the people on whom the safety management system is focused. These findings were echoed in a paper by Arocena & Núñez (2010) on the effectiveness of OHSMS in SMEs in Spain. They concluded there was good evidence in favour of the use of OHSMS to help reduce workplace injuries and ill-health and that the effectiveness of an:

… OHS system is determined by the quality of industrial relations, rate of unionization, intensity of price-based competition, access to public aid and training activities provided by the OHS public agencies, technology intensity, and the manual nature of workers’ tasks.

The issue of national culture is discussed in section 3.4 of this book. Other research papers on OHSMS discuss:

- safe place, safe person and safe system strategies (Makin, A.-M. & Winder, 2009)

- use of goals, criteria and requirements from a theoretical stance (Aven et al., 2006)sustainability of implementation projects (BOMEL Ltd, 2005b)

- evolution of SMS and barriers to their success (Hudson, 2001)

- reliability of OHS audits (Dyjack et al., 2003).

Viswanathan et al. (2024) reported that:

… U.S. establishments certified to OHSAS 18001 tend to be safer workplaces. OHSAS 18001 attracts establishments with fewer injury and illness cases than comparable establishments (a selection effect). Using propensity score matching and a difference-in-differences approach, we estimate that OHSAS 18001 certification reduces the total number of illness and injury cases by 20 percent and illness and injury cases associated with job transfers or restrictions by 24 percent. Managerial implications Our results indicate that becoming certified to a safety management standard can lead to meaningful improvements in workplace safety, and that OHSAS 18001 certification is a credible indicator of superior average safety performance, an important insight for buyers and suppliers. Given that OHSAS 18001 is the basis for the newer ISO 45001 standard that has quickly become the world’s third-most popular management system standard, this study provides promising evidence that ISO 45001 will also prove effective in distinguishing safer workplaces.

Similar work by Dyreborg et al. (2024) adds strength to the argument that OHSMSs that are already performing well may seek accreditation and then make further improvements.

2.2.1 PDCA and ISO management system standards

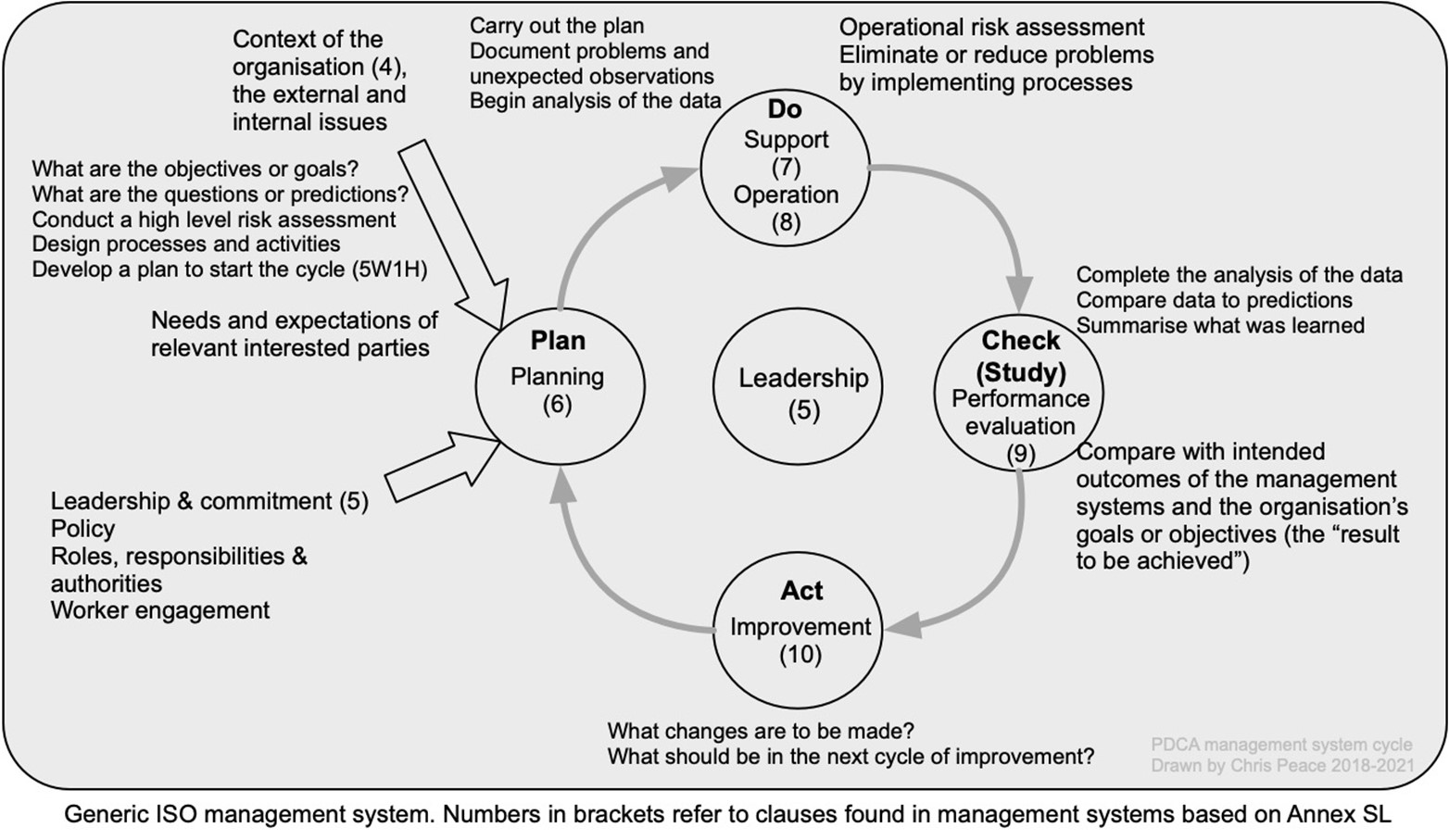

ISO management system standards use the Plan Do Check Act (PDCA) structure shown in Figure 8, annotated to show the high-level clause numbers and to include the Plan Do Study Act model (Moen, 2010) advocated by Deming. PDSA dates from work before the second world war on quality management systems that led to the PDCA. Note the similarities with SafePlus and the need for “… continuous improvement” (section 2.2.5).

Source: Author (2015-2025) using material from Moen (2010), ISO45001 (2018) and ISO/IEC Annex SL (2020)

Annex SL and management system standards

ISO/IEC Annex SL (2020) provides a high-level structure for ISO management system standards. Annex SL defines a management system as a “set of interrelated or interacting elements of an organization to establish policies and objectives and processes to achieve those objectives”. The definition then says in appended notes that a “management system can address a single discipline or several disciplines” and that the “system elements include the organization’s structure, roles and responsibilities, planning, operation, performance evaluation and improvement”. In other words, a single management system could include OHS, quality, environmental management, and other areas of interest.

AS/NZS ISO45001 (2018) Occupational health and safety management systems is based on Annex SL and the Plan Do Check Act model but some sub-clauses are specific to OHS. This common base suggests a health and safety professional (as distinct from a practitioner) could lead a project to develop a single management system for a PCBU, helping to avoid overlaps and gaps. See Peace (2024a).

2.2.2 IEC standards on dependability

The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) publishes standards on the reliability of plant (in the widest sense) and human factors. IEC60300-1 (2014) Dependability management: Guidance for management and application is part of a family of standards. It gives guidance on planning and implementation of a dependability management system through the life cycle of an item of plant considering other requirements including OHS and environmental issues.

While it does not directly relate to OHS, it gives guidance on availability, reliability, maintainability, and supportability under use. Dependable plant that is well maintained provides more certainty about achieving the objectives, its “ability to perform as and when required” (the definition of dependability).

The purpose of a system for managing dependability is to direct and control an organization with regard to dependability, coordinating with other disciplines to provide an efficient and integrated effort to achieve objectives. Organizational policies and objectives may include dependability policies and objectives, which then lead to a dependability management system that can effectively implement them (IEC60300.1, 2014, pp. 12-13).

Life cycle and OHS

A common cause of injuries and ill health due to plant is failure to consider constructability, operability, maintainability and disposal or abandonment as part of its life cycle. Life cycle is defined in IEC60300-1 as the “series of identifiable stages through which an item goes, from its conception to disposal”. Typical stages in the life cycle of an item are concept and definition; design and development; construction, installation, and commissioning; operation and maintenance; mid-life upgrading or life extension; decommissioning and disposal. These are expanded in the following table which includes a range of risk techniques that might be applied in each stage. Some are described in Chapter 21 of this book, IEC62198 (2013) and IEC/IEC/ISO31010 (2019). See Abbreviations used in this book for definitions.

Table 3. Typical phases in a project, decision points and examples of risk management techniques

|

Concept and definition |

Select pre-feasibility |

Design & develop: feasibility |

Construct, install, commission |

Operate & maintain |

Decommission, disposal or abandon |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Appraise opportunities.

Determine project feasibility & alignment with business strategy |

Select options.

Identify and appraise project development options; select the preferred one |

Define the project.

Finalise the scope and detail of the preferred option |

Deliver the project.

Produce an operating asset or service, consistent with the agreed scope |

Realise the benefits.

Evaluate the project outcome to ensure performance |

Closure.Ensure safe and acceptable closure |

| Focus of risk management activities | Strategic threats and opportunities | Risk-based options selection | Design and delivery strategy | Project delivery, test & handover | Operation and maintenance | Disposal & rehabilitation |

| Monitoring & review | Review risk assessment and related opportunities & threats | Are there alternative options including retaining the risk by choice? | Confirm context and risks have not changed | Identify and analyse operational risks

Treat to deliver controls |

Feedback deficiencies to designers for design improvements | Feedback deficiencies to designers for design improvements

Recycling opportunities |

| Possible risk management techniques | Concept mapping

Decision tree Horizon scanning Mind mapping PESTLE Scenario planning SWOT Risk workshops |

Decision tree

Process mapping Horizon scanning MCDA PESTLE SWIFT Risk workshops |

Decision tree

Environmental risk analysis Event tree analysis Fault tree analysis Process mapping Human reliability analysis MCDA SWIFT |

Nertney wheel

Bow-tie analysis FMECA HACCP HAZOP MORT Risk workshops |

Bow-tie analysis

Checklists FMECA HACCP HAZOP MORT Risk workshops |

Environmental risk analysis

Risk workshops |

Benefits of dependability management

The benefits of managing dependability may include:

1) meeting stakeholder requirements

2) achieving required service levels

3) increasing plant life expectancy and reducing life cycle costs

4) improving health and safety when hazards are eliminated or minimised

5) reducing adverse environmental effects when hazards are eliminated or minimised

6) improving product quality.

2.2.3 Common law duty of care and management of a PCBU

The New Zealand Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 is ultimately derived from English common law. Decisions under English cases sometimes give guidance on what the courts might expect in the management of a business or undertaking. For example, Denning LJ (1956) was a leading British judge who wrote in his decision in HL Bolton (Engineering) Co Ltd v TJ Graham & Sons Ltd:

A company may in many ways be likened to a human body. It has a brain and nerve centre which controls what it does. It also has hands which hold the tools and act in accordance with directions from the centre. Some of the people in the company are mere servants and agents who are nothing more than hands to do the work and cannot be said to represent the mind or will. Others are directors and managers who represent the directing mind and will of the company, and control what it does. The state of mind of these managers is the state of mind of the company and is treated by the law as such.

The relationship between English common law and management of a business was summarised as (Munkman, 1975, pp. 131-132):

The employer is responsible for the general organisation of the factory, mine or other undertaking; in short, he decides the broad scheme under which the premises, plant and men are put to work. This organisation or “system” includes such matters as the co-ordination of different departments and activities; the lay-out of plant and appliances for special tasks; the method of using particular machines or carrying out particular processes; the instruction of apprentices and inexperienced workers; and a residual heading, the general conditions of work, covering such things as fire precautions. An organisation of this kind is required – independently of safety – for the purpose of ensuring that the work is carried on smoothly and competently: and the principle of law is that in setting up and enforcing the system, due care and skill must be exercised for the safety of the workmen. Accordingly, the employer’s personal liability for an unsafe system – independently of the negligence of fellow-servants – is not founded on an artificial concept but is directly related to the facts of industrial organisation.

The report of the Robens Committee led to the British Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 (Lord Robens et al., 1972, pp. 14-15) and the report from the committee argued:

Promotion of safety and health at work is an essential function of good management. We are not talking here about legal responsibilities. The job of a director or senior manager is to manage. The boardroom has the influence, power and resources to take initiatives and to set the pattern. So far as the first of our prerequisites is concerned – awareness – the cue will be taken from the top. We know of a number of firms where the positive attitudes of the directors and senior managers are reflected in a remarkable degree of safety awareness at all levels throughout the firm. Conversely, if directors and senior managers are unable to find time to take a positive interest in safety and health, it is unrealistic to suppose that this will not adversely affect the attitudes and performance of junior managers, supervisors and employees on the shop floor. If, as we believe, the greatest obstacles to better standards of safety and health at work are indifference and apathy, employers must first look to their own attitudes. Moreover boardroom interest must be made effective. Good intentions at board level are useless if managers further down the chain and closer to what happens on the shop floor remain preoccupied exclusively with production problems (P14-15)

Are these opinions further evidence for the “interdependency characteristic of systems”? They should be seen as influential but not necessarily binding in New Zealand. As noted, the English common law duty of care was the basis of the British Health and Safety at Work Act 1974, and that legislation is the basis of the Australian Model Bill and New Zealand Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 (Brabant, 2024).

2.2.4 Leading and lagging indicators

Leading indicators are the most effective; they show whether planned or actual controls are working as intended. Individual observations of a work activity, or in a series – an inspection – can show where performance meets the standard expected in a standard operating procedure or safe system of work. Management inspections or walkabouts can be highly effective (see section 21.3.18). Other leading indicators include level of competency training and number of hazard reports closed out and removed from a risk register (Amick & Saunders, 2013; O’Neill et al., 2015) (Ward et al., 2008).

2.2.5 SafePlus

SafePlus is a “voluntary, health and safety performance improvement toolkit for businesses” (WorkSafe NZ, 2017) setting out “10 performance requirements that are fundamental to achieving good health and safety performance”. It is “organised into the three core concepts: leadership, worker engagement and risk management … underpinned by continuous improvement” listed below.

Leadership performance requirements

1.1 Officers effectively govern health and safety

1.2 Senior leaders/officers set a clear direction/vision for health and safety

1.3 Senior leaders understand the key health risks and safety risks in their business

1.4 Senior leaders monitor and verify risk control effectiveness

1.5 Senior leaders consider potential impacts on health and safety when making business decisions

2.1 Senior leaders set and communicate health and safety performance expectations and enable/support others to achieve them

2.2 Senior leaders recognise good practice and performance

2.3 Senior leaders stated commitments and actions are connected

2.4 Senior leaders create an environment of trust and fairness within the business

2.5 Senior leaders readily address unsafe actions, practices and situations

3.1 The business sets goals for health and for safety improvement

3.2 The business plans and implements actions to meet health goals and safety goals

3.3 The business monitors and evaluates progress against its health goals and safety goals

3.4 The business, with workers or their representatives, reviews and evaluates its effectiveness in risk management and broader health and safety management

3.5 The business uses ongoing monitoring, review and evaluation activity to inform business decisions and change

4.1 The business plans, directs and provides resources for the achievement of its goals, plans and activities

4.2 The business ensures that health and safety roles, accountabilities and responsibilities are clear and understood in all business relationships

4.3 The business checks that workers (including contractors) have the competence and resources necessary to perform their roles

4.4 The business integrates health and safety into procurement

4.5 The business proactively accommodates employee incapacity and ill health

Worker engagement requirements

5.1 The business’ methods and content of communication meet the needs of workers

5.2 The business is responsive in resolving disagreements or issues

5.3 The business communicates and shares learnings

6.1 The business ensures that workers have the opportunity for involvement in matters that may affect their health and safety

6.2 The business ensures that worker engagement, participation and representation practices are agreed, enabling, resourced and supportive

6.3 The business defines worker and representative authority to take action in matters that directly affect their health and safety

6.4 The business ensures workers and their representatives are effectively involved in decisions related to risk management

6.5 Workers and their representatives are directly involved in the setting and monitoring of health goals and safety goals for the business

Risk management performance requirements

7.1 The business uses a variety of methods to identify health risks and safety risks

7.2 The business applies the methods to the identification of both health risks and safety risks

7.3 The business applies the methods to the identification of risks in its supply chain and/or from the activities of other parties including contractors

7.4 The business applies the methods to the identification of risks associated with change, non-routine activities and emergencies

8.1 The business’ methods for assessing risks are relevant, effective, understood and agreed

8.2 The business applies the methods for risk assessment to all risks

8.3 The risk assessment process focuses the business’ attention and determines action

9.1 The business applies a hierarchy when controlling risks

9.2 The business identifies and applies a mix of controls to prevent, mitigate and respond to risks

9.3 The business risk assessments inform the identification and application of risk controls

9.4 The business identifies and uses guidance, standards and legal requirements when determining risk controls

9.5 The business consults, cooperates and coordinates with other parties including contractors, suppliers and those it works with or alongside when controlling risks

10.1 The business checks that identified controls for health risks and safety risks are understood and implemented

10.2 The business checks that other parties understand and implement agreed risk controls

10.3 The business tests and verifies the effectiveness of risk controls

10.4 The business identifies and takes action to strengthen risk control effectiveness

10.5 The business investigates, learns and improves risk management from success and failure

The performance requirements are assessed using a three-level maturity scale: developing, performing, and leading. How well do these performance requirements aid interdependency characteristics of systems?

2.2.6 Resources used in the development of SafePlus

SafePlus was developed for use in New Zealand by WorkSafe, ACC and the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment 2013-2017. Despite an Official Information Act request it has not been possible to access all the resources used by the officials (some were no longer available) but those that could be located are listed below. Each performance requirement appears to correlate with the requirements of ISO45001 but in January 2025 there had been no peer-reviewed research confirming the validity of SafePlus. Neither had the standard been the subject of peer-reviewed research although work by Viswanathan et al. (2024) suggested that ISO45001 might be reliable.

Amick, B. C., & Saunders, R. (2013). Developing leading indicators of work injury and illness [Report]. Institute for Work & Health, Ontario https://www.iwh.on.ca/sites/iwh/files/iwh/reports/wh_issue_briefing_leading_indicators_2013.pdf

Bigelow, P., & Robson, L. (2006). Occupational health and safety management audit instruments: A literature review [Research Report]. Institute for Work & Health, Ontario www.iwh.on.ca

Blewett, V., & O’Keeffe, V. (2011). Weighing the pig never made it heavier: Auditing OHS, social auditing as verification of process in Australia. Safety Science, 49(7), 1014-1021. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2010.12.010

Bluff, E. (2011). Something to think about: Motivations, attitudes, perceptions and skills in work health and safety [Research Report wp MAPS02]. Australian National University, Canberra

Business NZ. (2013). Wellness in the Workplace [Report]. Author, Wellington www.businessnz.org.nz

Bye, R. J., Rosness, R., & Røyrvik, J. O. D. (2016, 2016/01/01/). ‘Culture’ as a tool and stumbling block for learning: The function of ‘culture’ in communications from regulatory authorities in the Norwegian petroleum sector. Safety Science, 81, 68-80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2015.02.015

Clarke, S. (2000). Safety culture: under-specified and overrated? International journal of management reviews: IJMR, 2(1), 65-90. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2370.00031

Costante, A., Saunders, R., & Mustard, C. (2014). Suppression of workplace injury and illness claims: Summary of evidence in Canada [Research Report]. Institute for Work & Health, Ontario https://www.iwh.on.ca/

Cummings, R. (2006). Expert views on the evidence base for effective health and safety management [Research Report HSL/2006/109]. Health and Safety Laboratory, Sheffield https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/hsl/social.htm

Franche, R. L., Cullen, K., Clarke, J., Irvin, E., Sinclair, S., & Frank, J. (2005, Dec). Workplace-based return-to-work interventions: a systematic review of the quantitative literature. J Occup Rehabil, 15(4), 607-631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-005-8038-8

Frick, K. (2011). Worker influence on voluntary OHS management systems – A review of its ends and means. Safety science, 49(7), 974-987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2011.04.007

Haight, J., & Thomas, R. (2003). Intervention effectiveness research: A review of the literature on leading indicators. Chemical Health & Safety, 10(2), 21-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1074-9098(02)00454-9

HSE. (2001). A guide to measuring health & safety performance [Guidance Note]. HSE Books, Sudbury https://www.hse.gov.uk/opsunit/perfmeas.pdf

ILO-OSH: 2009 Guidelines on occupational safety and health management systems, International Labor Organization, Geneva. http://www.ilo.org/

International Labor Organization: 2001 Guidelines on occupational safety and health management systems, Author, Geneva. http://www.ilo.org/

International Labor Organization. (2002). Managing disability in the workplace [Code of Practice]. Author, Geneva https://www.ilo.org/

Kankaanpaa, E. (2010). Economic Incentives as a Policy Tool to Promote Safety and Health at Work. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health, 36(4), 319-324. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3048

La Tourette, T., & Mendeloff, J. (2008). Mandatory workplace safety and health programs: Implementation, Effectiveness, and Benefit-cost Trade-offs [Technical Report 604]. RAND Corporation, http://www.rand.org/t/RR1537

Mischke, C., Verbeek, J. H., Job, J., Morata, T. C., Alvesalo‐Kuusi, A., Neuvonen, K., Clarke, S., & Pedlow, R. I. (2013). Occupational safety and health enforcement tools for preventing occupational diseases and injuries. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(8). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010183.pub2

O’Neill, S., Cheung, A., & Wolfe, K. (2013). Issues in the assurance and verification of work health and safety information]. Safe Work Australia, NSW https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/1703/issues-assurance-verification-wh-_information-review.pdf

OHSAS18001: 2007 Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems – Requirements, British Standards Institution, London.

Pezzullo, L., & Crook, A. (2006). The Economic and Social Costs of Occupational Disease and Injury [Technical Publication 4]. National Occupational Health and Safety Advisory Committee, Wellington https://cohsr.aut.ac.nz/resources

Podgórski, D. (2015, 3//). Measuring operational performance of OSH management system – A demonstration of AHP-based selection of leading key performance indicators. Safety Science, 73(0), 146-166. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2014.11.018

Predictive Solutions Corporation. (2012). Predictive Analysis in Workplace Safety: Four ‘Safety Truths’ that Reduce Workplace Injuries: [Report]. Author, Pennsylvania https://ohsonline.com/whitepapers/2012/04/predictive-analysis-in-workplace-safety/asset.aspx

Robson, L., Clarke, J., Cullen, K., Bielecky, A., Severin, C., Bigelow, P., Irvin, E., Culyer, A., & Mahood, Q. (2005). The Effectiveness of Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems: A Systematic Review [Research Report]. Institute for Work & Health, Toronto http://www.iwh.on.ca/products/ohsms.php

Robson, L., Macdonald, S., Gray, G. C., Van Eerd, D., & Bigelow, P. L. (2012, Feb). A descriptive study of the OHS management auditing methods used by public sector organizations conducting audits of workplaces: Implications for audit reliability and validity. Safety Science, 50(2), 181-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2011.08.006

Robson, L. S., & Bigelow, P. L. (2010, Mar-Apr). Measurement properties of occupational health and safety management audits: a systematic literature search and traditional literature synthesis. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 101 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), S34-S40. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03403844

Robson, L. S., Clarke, J. A., Cullen, K., Bielecky, A., Severin, C., Bigelow, P. L., Irvin, E., Culyer, A., & Mahood, Q. (2007). The effectiveness of occupational health and safety management system interventions: A systematic review. Safety Science, 45(3), 329-353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2006.07.003

SA/SNZ4801: 2001 Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems – specification with guidance for use, Standards New Zealand, Wellington.

Tappura, S., Sievänen, M., Heikkilä, J., Jussila, A., & Nenonen, N. (2015, 2015/01/01/). A management accounting perspective on safety. Safety Science, 71, 151-159. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2014.01.011

Walters, D., Sampson, H., & James, P. (2012). The limits of influence: The role of supply chains in influencing health and safety management in two sectors [Research Report 12.2]. IOSH, Leicester https://iosh.com/guidance-and-resources/downloads/research-library/the-limits-of-influence

WorkCover NSW. (2014). National self-insurer OHS management system audit tool [Report]. Author, Canberra https://www.worksafe.vic.gov.au/resources/national-self-insurer-ohs-management-system-audit-tool-version-3

Wren, J. (1996). The Transformation of New Zealand’s Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) Legislation and Administration From 1981 to 1992: A Case of Reactionary Politics. Labour, Employment and Work in New Zealand, 201-211. https://doi.org/10.26686/lew.v0i0.978

2.3 Chapter summary

This chapter has outlined the need to see PCBUs in terms of management systems and to think about the “interdependency characteristic of systems”. The relationship of such systems to the common law origins of the British Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 1974 and now the New Zealand Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 is noted, leading to the question: Can a PCBU comply with the HSWA if it lacks a management system?

In New Zealand development of the common law duty of care stopped with implementation of the accident compensation system, and we lack a substantial body of legal decisions to inform compliance with our 2015 legislation. We also lack a body of research in management science in relation to the management of OHS.

2.4 References used in this chapter

Amick, B. C., & Saunders, R. (2013). Developing leading indicators of work injury and illness [Report]. Institute for Work & Health, Ontario. https://www.iwh.on.ca/sites/iwh/files/iwh/reports/wh_issue_briefing_leading_indicators_2013.pdf

Arocena, P., & Núñez, I. (2010). An empirical analysis of the effectiveness of occupational health and safety management systems in SMEs. International Small Business Journal, 28(4), 398-419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242610363521

AS/NZS ISO45001: 2018 Occupational health and safety management systems: Requirements with guidance for use, Standards New Zealand, Wellington.

Aven, T., Vinnem, J., & Roed, W. (2006). On the Use of Goals, Quantitative Criteria and Requirements in Safety Management. Risk Management: an international journal, 8(2), 118-132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.rm.8250006

BOMEL Ltd. (2005b). Occupational health and safety support systems for small and medium sized enterprises [Research Report RR0410]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Bornstein, S., & Hart, S. (2010). Evaluating occupational safety and health management systems: a collaborative approach. Policy and practice in health and safety, 8(1), 61-76.

Brabant, D. (2024). Health and Safety Law from the Industrial Revolution to the New Zealand Health and Safety at Work Act 2015. NZ Journal of Health and Safety Practice, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.26686/nzjhsp.v1i2.9546

Cohen, A. (1977). Factors in successful occupational-safety programs. Journal of Safety Research, 9(4), 168-178.

Cohen, A., Smith, M., & Cohen, H. H. (1975). Safety Program Practices in High vs Low Accident Rate Companies: An interim report (questionnire phase) [Research Report 75-185]. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Cincinnati.

HL Bolton (Engineering) Co Ltd v TJ Graham & Sons Ltd [1956] Court of Appeal.

Dyjack, D. T., Redinger, C. F., & Ridge, R. S. (2003). Health and Safety Management System Audit Reliability Pilot Project. AIHA Journal, 64(6), 785-791. http://www.informaworld.com/10.1080/15428110308984873

Dyreborg, J., Thorsen, S. V., Madsen, C. U., et al. (2024). Effectiveness of OHSAS 18001 in reducing accidents at work. A follow-up study of 13,102 workplaces. Safety Science, 177, 106573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2024.106573

Fernández-Muñiz, B., Montes-Peón, J. M., & Vázquez-Ordás, C. J. (2012). Occupational risk management under the OHSAS 18001 standard: analysis of perceptions and attitudes of certified firms. Journal of Cleaner Production, 24, 36-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.11.008

Gallagher, C., Underhill, E., & Rimmer, M. (2001). Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems: A Review of their Effectiveness in Securing Healthy and Safe Workplaces [Research Report 1702]. National Occupational Health and Safety Commission, Sydney. https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/1702/ohsmanagementsystems_reviewofeffectiveness_nohsc_2001_archivepdf.pdf

Hudson, P. (2001). Safety Management and Safety Culture The Long, Hard and Winding Road. Occupational Health & Safety Management Systems: Proceedings of the First National Conference, Melbourne, Australia, Crown Content. www.crowncontent.com.au

IEC60300.1: 2014 Dependability management – Part 1: Guidance for management and application, International Electrotechnical Commission, Geneva.

IEC62198: 2013 Managing risk in projects – Application guidelines, International Electrotechnical Commission, Geneva.

IEC/ISO31010: 2019 Risk management – Risk assessment techniques, International Electrotechnical Commission,, Geneva.

ILO C155: 1981 Occupational Safety and Health Convention, International Labour Organization, Geneva. https://www.ilo.org/

ISO45001: 2018 Occupational health and safety management systems: Requirements with guidance for use, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

ISO/IEC Annex SL. (2020). Proposals for management system standards. In Directives, Part 1: Consolidated ISO Supplement – Procedures specific to ISO (11th ed.). International Standards Organization. https://www.iso.org/directives-and-policies.html

Lord Robens, A., Beeby, G., Pike, M., et al. (1972). Safety and Health at Work: Report of the Committee, 1970-72 [Report Cmnd 5034]. HMSO, London. http://www.mineaccidents.com.au/uploads/robens-report-original.pdf

Makin, A.-M., & Winder, C. (2009). Managing hazards in the workplace using organisational safety management systems: a safe place, safe person, safe systems approach. Journal of Risk Research, 12(3/4), 329-343. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669870802658998

Moen, R. (2010). Foundation and History of the PDSA Cycle [Electronic article]. https://www.praxisframework.org/

Munkman, J. (1975). Employer’s liability at common law (8th ed.). Butterworths.

O’Neill, S., Wolfe, K., & Holley, S. (2015). Performance measurement, incentives and organisational culture:Implications for leading safe and healthy work [Research Report]. Safe Work Australia, NSW. https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/

Robson, L. S., Clarke, J. A., Cullen, K., et al. (2007). The effectiveness of occupational health and safety management system interventions: A systematic review. Safety Science, 45(3), 329-353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2006.07.003

Rocha, R. S. (2010). Institutional effects on occupational health and safety management systems. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries, 20(3), 211-225. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hfm.20176

Viswanathan, K., Johnson, M. S., & Toffel, M. W. (2024). Do safety management system standards indicate safer operations? Evidence from the OHSAS 18001 occupational health and safety standard. Safety Science, 171, 106383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2023.106383

Walker, D., & Tait, R. (2004). Health and safety management in small enterprises: an effective low cost approach. Safety Science, 42(1), 69-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-7535(02)00068-1

Ward, J., Haslam, C., & Haslam, R. (2008). The impact of health and safety management on organisations and their staff [Research Report]. IOSH Publishing Ltd, Leicester. http://www.iosh.co.uk/impmanagement

WorkSafe NZ. (2017). SafePlus Performance Requirements [Guidance Note]. WorkSafe NZ, Wellington. www.safeplus.nz

Zwetsloot, G., & Kuhl, K. (2013). What are occupational safety and health management systems and why do companies implement them? EU-OSHA. https://oshwiki.eu/wiki/What_are_occupational_safety_and_health_management_systems_and_why_do_companies_implement_them%3F