12 Assessing risks and uncertainty – pitfalls and a solution

12.1 Chapter overview

Links with management system standards, ISO31000 and SafePlus.

See SafePlus requirements and clauses 6.1, 7.5 and 8.1 in management system standards.

Definitions of italicised terms are in the Glossary.

Readings and resources

Check for webinars, interviews, and videos for complementary resources.

Key questions

- What are the OHS objectives of the organisation, activity, system, or item?

- What are the uncertainties about their achievement?

- What is or will be the impact of artificial intelligence on the business?

Useful management techniques

Literature or document review (see section 21.3.22).

12.2 What is “risk assessment”?

Risk assessment is (ISO31000, 2018) the “overall process of risk identification, risk analysis and risk evaluation”. The substitution approach shows this becomes:

The “overall process of identification, analysis and evaluation of the effect of uncertainty on objectives”.

As part of an assessment it will be important to communicate and consult with stakeholders to keep them in touch with what you are doing. You should also monitor and review the context and risk-related information you are using to see if it has changed in circumstances. It is also possible some change will make the risk assessment more urgent (with a change in terms of reference) or redundant (in which case it should be halted).

The best available information

An organisation is a “person or group of people that has its own functions with responsibilities, authorities and the relationships to achieve objectives”(ISO/IEC Annex SL, 2020). The larger the organisation the less any one person can know about effects of uncertainty on objectives – about risk – in that organisation and the business environment it operates in. We therefore need to engage with stakeholders (also called interested parties) who may know something or hold a view that can affect the organisation.

ISO31000 (2018, p. 3) sets out principles for effective risk management. Principle f states:

“Best available information

The inputs to risk management are based on historical and current information, as well as on future expectations. Risk management explicitly takes into account any limitations and uncertainties associated with such information and expectations. Information should be timely, clear and available to relevant stakeholders.”

It is not necessary to carry an encyclopaedia of data in your head – much reliable information is accessible free of charge – but the relevance and reliability of grey literature need to be judged if it is to be used to inform a decision.

Gathering the best available information can be done in a variety of ways, including (but not limited to) those described in this book. Probably the most powerful way of gathering the best available information is engagement, using conversations, interviews and workshops with as wide a range of stakeholders as possible.

Benefits of an effective risk assessment

Application of an effective risk assessment may have major positive effects beyond those expected (Anon, 2023; Morris & Raffle, 1954).

12.3 When to carry out a “risk assessment”

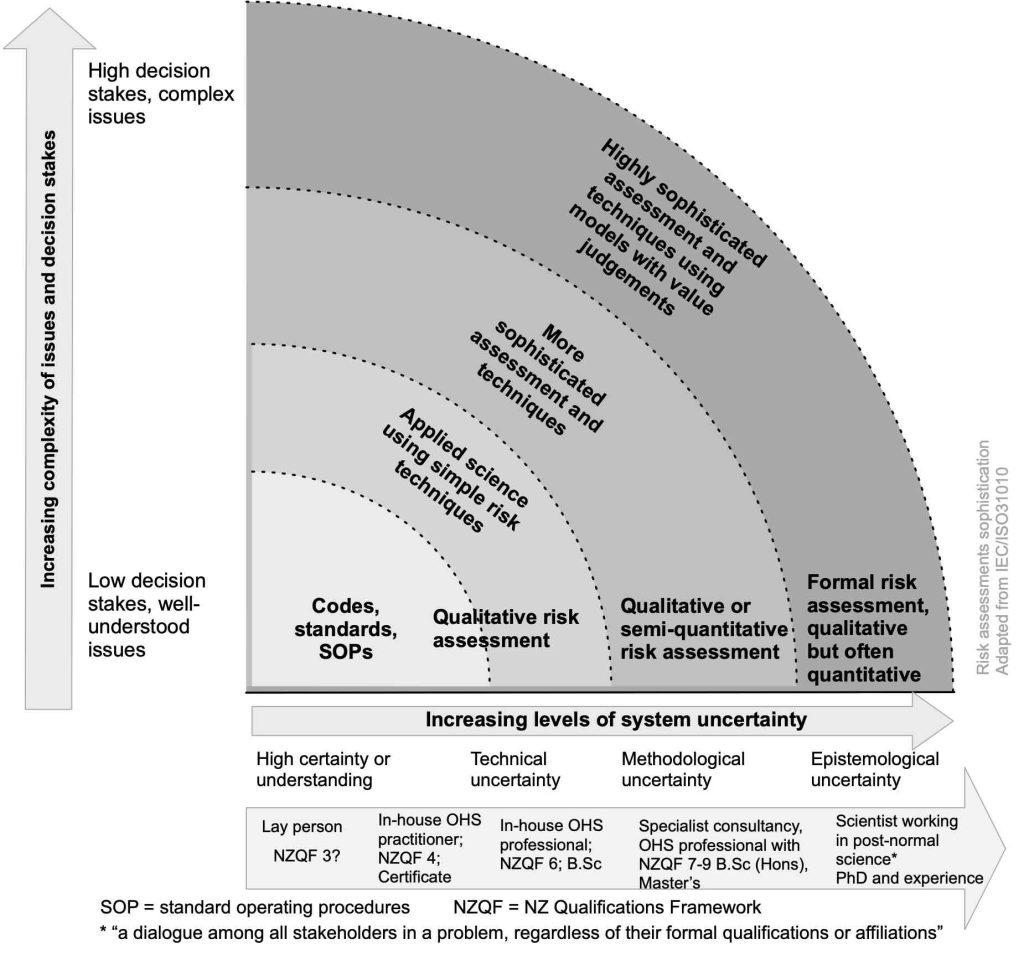

Risk assessments help inform effective decisions but may not be necessary if there is low uncertainty and the decision is simple. The greater the uncertainty and/or complexity the greater the competence an assessment team or assessor should have. This is illustrated in Figure 37.

In the diagram, codes, standards, standard operating procedures (SOPs) should be written in ways that workers and line managers are able to interpret and apply them in low-complexity, well understood “if-then” circumstances. As uncertainty and complexity increase, simple risk assessments using qualitative techniques should be carried out by trained managers or team leaders who have the competency to develop the required information. More complex risks would require qualitative (sometimes quantitative) work by an in-house professional or a professional consultancy, while highly complex risks with high uncertainty may require quantitative and qualitative work by scientists.

In the final Whakaari case Judge Thomas decided (WorkSafe NZ v Whakaari Management Ltd, 2023) that the “charge under s 37 of the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 is proved and WML is convicted”. In his full decision the judge wrote:

88. Had WML complied with its duty and obtained the necessary expert advice on risk and health and safety, it would have fully understood the risk. It would have had two options:

(a) stop tours entirely 101. The failure to do so exposed any individual to a risk of death or serious injury; and

(b) implement effective controls if that were possible. Such controls, to be effective, would have eliminated or minimised the risk. The failure to do so resulted in tours occurring to Whakaari without adequate controls, exposing individuals to a risk of death or serious injury.

101. Dr Peace considered this the only reasonable outcome: formal statement of Christopher Peace, exhibit WSE.008.02502 at paras 7.23 and 7.26.

12.4 OHS practitioners, professionals, and expert witnesses

How should an occupational health and safety professional distinguish themselves from a practitioner (INSHPO, 2017)? An IOSH report (Smith, A. & Wadsworth, 2009) and at least three articles have indicated what might be expected (Lloyd & Healy, 2017; Lund, O. & Aldridge, 2020; Nicholson & Welsh, 2019). Read these articles to help get clear what the job of a health and safety professional is.

In Britain, Regulation 7 of the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations (1999) requires that:

7.—(1) Every employer shall, subject to paragraphs (6) and (7), appoint one or more competent persons to assist him in undertaking the measures he needs to take to comply with the requirements and prohibitions imposed upon him by or under the relevant statutory provisions and by Part II of the Fire Precautions (Workplace) Regulations 1997.

The word “competent” can be interpreted using the Annex SL definition of “competence”.

“ability to apply knowledge and skills to achieve intended results”

In the Britain, OHS practitioners have been prosecuted and convicted under the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 (Bridges, 2015a; Lamy, 2022b; Mundell, 2019).

Our duty of care

In New Zealand, a prosecution by WorkSafe of a PCBU making animal feed (Anon, 2019; WorkSafe NZ v Precision Animal Supplements Ltd, 2018b) could have (but did not) include the consultant who lacked the competence to advise on the substances that workers were exposed to.

If a health and safety consultant is commissioned by a PCBU to provide particular services, they should commence and complete that work in a reasonable time. Safe Business Solutions (SBS, a safety consultancy) “[1] … were contracted by another company who I shall refer to as “Westown” to devise a traffic management plan. SBS did not provide an effective traffic management plan and as a result one of Westown’s workers was hit by a moving vehicle and suffered serious injury. … [28] For reasons that are suppressed the amount that SBS are to actually pay is $70,000.” (Worksafe New Zealand v Safe Business Solutions Ltd, 2024)

The duty of care owed by health and safety practitioners in NZ was strongly emphasised by Judge Ruth in the prosecution of William Sullivan for lying to WorkSafe when it investigated the near-death of a worker (R v William Sullivan, 2023).

[23] If anyone in this company has any direct responsibility for Mr Palmer’s plight it is you, it is on your shoulders. Your dereliction of duty is outrageous. Why you then continued with the lie I cannot know, but you have to be held to account and so do those who undertake work of a health and safety nature. It is absolutely imperative that health and safety regulations be strictly abided by and that people do not put their own interests before the health and safety of those who they are tasked with caring for. They must ensure that employees do work in a safe environment, so that they do go home at the end of the day not in an ambulance but under their own steam.

[27] The real question is, how do I impose a sentence that is consistent with the purposes and principles of the Sentencing Act in relation to the remaining nine month residual sentence? My view is that in a case such as this that deterrence, both general and specific, must be the overriding and overwhelmingly important factors of this sentencing. Those who are tasked with and who have obligations under health, work and safety legislation must get the message that this is serious and a failure to carry out obligations in the way you failed to has to have consequences that everyone can understand.

[28] I take the view after having very carefully thought about all of the sentencing options in the Sentencing Act, having regard to all of the submissions and having regard to such case law as there is, that there is no other sentence that can meet the Sentencing Act requirements but a term of imprisonment.

[29] You will therefore be imprisoned for nine months.

Was Sullivan a worker who owed a duty of care to the injured worker, Mr Palmer (see section 45(b) HSWA)? Was Sullivan “reckless” (see section 47, HSWA)? For more on “recklessness” see Nicholson & Wray (2024).

Expert witnesses

We also need to remember that any professional person who is called as an expert witness will need to demonstrate their qualifications as a witness and how and why they reached their opinion. The Evidence Act (2006), section 4, defines “expert” to mean ”a person who has specialised knowledge or skill based on training, study, or experience”. It also defines expert evidence to mean “the evidence of an expert based on specialised knowledge or skill of that expert and includes evidence given in the form of opinion”. Section 25 of the Act describes the admissibility of expert opinion evidence, saying that it is admissible “if the fact-finder is likely to obtain substantial help from the opinion in their understanding of other evidence in the proceeding or in ascertaining any fact that is of consequence to the determination of the proceeding”.

A case in the England showed the importance of understanding the status and duties of expert witnesses and a summary article merits reading (Scognamiglio, 2019). As a result of their lies and deceit, a lawyer and medical doctor were sent to prison.

It may not be enough for a health and safety practitioner say “I used my professional judgement”; such a judgement should be founded on how the question was answered using the best available information, elicited by using relevant management techniques.

The process suggested in this, and subsequent, chapters might help the court understand how a professional reached their conclusions.

12.5 Common pitfalls associated with risk assessments

Some research found the following common pitfalls associated with occupational health and safety-related risk assessments (Gadd et al., 2004). While the research was based on safety-related risk assessments, most of the findings can be applied more widely.

| Carrying out a risk assessment to attempt to justify a decision that has already been made

Carrying out a risk assessment using inappropriate good practice Carrying out a detailed quantified risk assessment without first considering whether any relevant good practice was applicable, or when relevant good practice exists Making decisions on the basis of individual risk estimates when societal risk is the appropriate measure Only considering the risk from one activity Dividing the time spent on the hazardous activity between several individuals – the ‘salami slicing’ approach to risk estimation Not involving a team of people in the assessment or not including employees with practical knowledge of the process/activity being assessed Not linking hazards with risk controls |

Using a generic assessment when a site-specific assessment is needed Ineffective use of consultants Failing to fully consider all possible outcomes Failing to identify all hazards associated with a particular activity Inappropriate use of data Inappropriate definition of a representative sample of events Inappropriate use of risk criteria Not considering ALARP or further measures that could be taken Inappropriate use of cost benefit analysis Using ‘Reverse ALARP’ arguments (ie, using cost benefit analysis to attempt to argue that it is acceptable to reduce existing safety standards) Not doing anything with the results of the assessment |

After the global financial crisis, research found the following six causes of enterprise risk management failures (Stulz, 2008).

1) Mismeasurement of known risks

2) Failure to take risks into account when making decisions

3) Failure in communicating the risks to top management

4) Failure in monitoring risks

5) Failure in managing risks

6) Failure to use appropriate risk metrics

12.6 WorkSafe SafePlus requirements

The SafePlus model requires that (WorkSafe NZ, 2017):

7.1 The business uses a variety of methods to identify health risks and safety risks

7.2 The business applies the methods for the identification of both health risks and safety risks

7.3 The business applies the methods to the identification of risks in its supply chain and/or from the activities of other parties including contractors

7.4 The business applies the methods to the identification of risks associated with change, non-routine activities and emergencies

8.1 The business’ methods for assessing risks are relevant, effective, understood and agreed

8.2 The business applies the methods for risk assessment to all risks

8.3 The risk assessment process focuses the business’ attention and determines action

SafePlus is covered in section 2.2.5 of this book on occupational health and safety management systems.

12.7 Useful assessment and management techniques

Using a systematic and structured approach to assessment and management of uncertainty is more likely to give effective results than simple professional judgement. An international standard IEC/ISO31010 (2019) sets out 40 techniques and includes a graphic adapted from Peace (2017a) (see section 21.2 of this book) identifying where a range of techniques might be used.

Several other sources set out potentially useful structured techniques that can be applied in the ISO31000 process, including a research report by Goldberg et al (1994) for NASA that provided a useful system engineering “toolbox” for design-oriented engineers; a chapter by Swallom et al (2003, pp. 497-540) that describes system safety principles and methods; and a research report for the UK Health and Safety Executive (Gould et al., 2005) that provides a review of hazard identification techniques.

12.8 Carrying out an assessment: the risk canvas

In the block course we will use the risk canvas, an A1 pre-printed sheet, to help understand what an effective assessment might cover and when officers might rely on such an assessment. Electronic copy will be provided to you on Nuku.

The risk canvas can be used for any “risk” and as described here, will work reasonably well for proposals or activities to be reported on to executive management or “officers” of a business or undertaking. It helps a workshop group to work through a structured process using structured techniques to help gather the best available information to inform decisions about the effects of uncertainty on identified objectives. It also acts as a simple tool to help record information.

Use of the risk canvas will be covered in more detail over the next few chapters.

After you have worked on your risk canvas …

Uncertainties

The definition of risk in ISO31000 Risk management: principles and guidelines is the “effect of uncertainty on objectives”. Looking at your risk canvas, have you shown where there is uncertainty, perhaps because, for example:

- the information that was available to you was not the best available information

- assumptions were found to be untenable

- the process for the assessment was incomplete

- some controls are not effective, perhaps assumed to be effective

- there are control gaps.

Reporting, monitoring, and review

Later we will cover reporting, monitoring, and review in more detail. Here it is enough to know that when you have finished work using the risk canvas you can re-draw your bow tie analysis with a suitable graphics package and insert it into a report. You could also use Post-it notes and a flipchart sheet or glass wall to capture a large bow tie analysis.

The report becomes an important record of how a proposal or activity was assessed. It should be saved for regular review but will also help anyone who is monitoring or reviewing the activity or carrying out an audit or review. Review each assessment of a “major effect of uncertainty on objectives” at least annually as part of the routine cycle of management reporting. The review should be by a competent but independent person.

Using the risk canvas in this way should give you a reasonable assessment, including some identified treatments (action points) you or colleagues need to follow up on. Some stakeholders may be satisfied with your work and findings, but some may be concerned about the findings or the level of uncertainty and may ask you for better information. Either outcome will be an assessment success because awareness of uncertainty and assumptions has been raised.

12.9 Chapter summary

This chapter has covered some major issues, including:

- there is no commonly agreed definition of “risk”; we should therefore focus on uncertainty, its effect on objectives, and assumptions made

- following a good assessment process, informed by reliable techniques, will help gather the best available information

- a health and safety practitioners and professionals owe a duty of care to our fellow workers and (if consultants) our clients.

12.10 References used in this chapter

Anon. (2019, January/February). Workers’ complaints ignored. Safeguard, 173, 6.

Anon. (2023, 7 September). How London bus drivers changed the world, and led to the invention of exercise. The Economist.

Bridges, K. (2015a, March). Could that have been me? Safety & Health Practitioner.

Evidence Act (2006). New Zealand http://www.legislation.govt.nz/

Gadd, S., Keeley, D., & Balmforth, H. (2004). Pitfalls in risk assessment: examples from the UK. Safety Science, 42(9), 841-857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2004.03.003

Goldberg, B., Everhart, K., Stevens, R., et al. (1994). System Engineering “Toolbox” for Design-Oriented Engineers [Reference Publication 1358]. NASA, Alabama. http://snebulos.mit.edu/

Gould, J., Glossop, M., & Ioannides, A. (2005). Review of hazard identification techniques [Research Report HSL/2005/58]. Health and Safety Laboratory, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/hsl/

IEC/ISO31010: 2019 Risk management – Risk assessment techniques, International Electrotechnical Commission,, Geneva.

INSHPO. (2017). The Occupational Health and Safety Professional Capability Framework: A Global Framework for Practice [Standard]. International Network of Safety and Health Practitioner Organizations, Park Ridge, Il, USA. https://www.inshpo.org/

ISO31000: 2018 Risk management – Guidelines, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

ISO/IEC Annex SL. (2020). Proposals for management system standards. In Directives, Part 1: Consolidated ISO Supplement – Procedures specific to ISO (11th ed.). International Standards Organization. https://www.iso.org/directives-and-policies.html

Lamy, M. (2022b). ‘Obvious and ignored risk’ led to scaffolder’s death in church collapse [Case Study]. IOSH Magazine. https://www.ioshmagazine.com/2022/03/29/obvious-risk-ignored-which-led-scaffolders-death-church-collapse

Lloyd, A., & Healy, N. (2017). Consultants at risk. Safeguard, (162), 8.

Lund, O., & Aldridge, P. (2020, March/April). Stay in your lane. Safeguard, (180).

Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations (1999), The Stationery Office, London. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/

Morris, J. N., & Raffle, P. A. B. (1954). Coronary Heart Disease in Transport Workers. A Progress Report. British Journal of Industrial Medicine, 11(4), 260-264. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.11.4.260

Mundell, K. (2019, October). Caravan site and safety consultant fined after holiday maker nearly drowned. IOSH Magazine. www.ioshmagazine.com

Nicholson, G., & Welsh, O. (2019, March/April). Inexpert advice. Safeguard, (174), 30.

Nicholson, G., & Wray, E. (2024). Crime and Punishment: Is the existing offence for reckless breaches of health and safety duties working, or does New Zealand need something new? NZ Journal of Health and Safety Practice, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.26686/nzjhsp.v1i2.9544

Peace, C. (2017a). The reasonably practicable test and work health and safety-related risk assessments. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 42(2), 61-78.

R v William Sullivan [2023] NZDC 15041 Nelson District Court. https://www.lexology.com/

Scognamiglio, D. (2019). Liverpool Victoria Insurance Co Ltd v Zafar. Lexology. https://www.lexology.com/

Smith, A., & Wadsworth, E. (2009). Safety culture, advice and performance [Research Report]. IOSH Publishing Ltd, Leicester. http://www.iosh.co.uk/

Stulz, R. M. (2008). Risk Management Failures: What Are They and When Do They Happen? [Working Paper 2008-18]. http://www.ssrn.com/abstract=1278073

Swallom, D., Lindberg, R., & Smith-Jackson, T. (2003). System Safety Principles and Methods. In Handbook of Human Systems Integration (pp. 497-540). John Wiley & Sons.

WorkSafe NZ. (2017). SafePlus Performance Requirements [Guidance Note]. WorkSafe NZ, Wellington. www.safeplus.nz

WorkSafe NZ v Precision Animal Supplements Ltd [2018b] NZDC 19342 Ashburton District Court. https://www.districtcourts.govt.nz/

Worksafe NZ v Safe Business Solutions Ltd [2024] NZDC 19761 New Plymouth District Court.

WorkSafe NZ v Whakaari Management Ltd [2023] NZDC 23224 Auckland District Court.