18 Risk assessment process: Evaluating the results

18.1 Chapter overview

Cross reference to ISO31000 (2009 para 5.4.4; 2018 para 6.4.4) and ISO45001 (2018 paras 6.1.2 & 8.1.2).

Check for key readings, webinars, and videos for complementary resources.

Definitions of italicised terms are in the Glossary.

Relevant law

- Health and Safety at Work Act 2015

- Health and Safety at Work (General Risk and Workplace Management) Regulations 2016

- Health and Safety at Work (Major Hazard Facilities) Regulations 2016

Key questions

What is or will be the impact of artificial intelligence on the business?

If risk is the “effect of uncertainty on objectives“:

- what are the objectives of the organisation, activity, system, or item?

- how much uncertainty and its effects on objectives has your analysis found?

- if that level of uncertainty is unacceptable, how can it be changed?

- what is the first priority of a PCBU? (Cribby, 2023)

Useful management techniques

You may need to workshop (section 21.3.40) some effects of uncertainty on objectives (“risks”) to help judge whether they are acceptable “as is” or require modification by treatment to make them acceptable. In a workshop the results from an assessment should be openly disclosed, including any estimates or assumptions.

18.2 What is risk evaluation?

Risk evaluation is (ISO31073, 2022) the: “process of comparing the results of risk analysis with risk criteria to determine whether the level of risk and/or its magnitude is acceptable or tolerable”. In other words, when the results of the analysis are compared with the criteria, are the level of uncertainty or the consequences unacceptable? If yes, it must be treated. Before deciding if the level of risk and/or its magnitude is acceptable or tolerable, decision-makers need to ask and get answers to the following questions.

- Did this assessment follow a good process?

- Did it provide the best available information?

- What are our criteria for acceptance or rejection of such uncertainty and its effects?

- Is the nature of this uncertainty, and its effects, acceptable?

- Does this level of uncertainty exceed our criteria and/or are its effects outside our appetite?

Tests for use in evaluations

We could rely on individuals to make decisions about risks and whether they are acceptable. This is often the case if they do not understand that the issue is uncertainty and its effects. However, governments and the courts have established some policy and requirements for decision-makers to follow including:

- “reasonably practicable” (section 22, Health and Safety at Work Act)

- “due diligence” (section 44, Health and Safety at Work Act)

- “care, diligence, and skill” (section 137, Companies Act 1993)

- “reasonable grounds” (Companies Act 1993, Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013).

18.2.1 What might be included in a “reasonably practicable” evaluation of risk?

The factors to be considered when assessing if a risk is as low as reasonably practicable have been expanded on by the HSE and other writers and are summarised in the following table.

Table 32. Summary of factors affecting demonstration of reasonably practicable

| Factor | Issues to consider |

| (a) likelihood of the hazard (cause) or risk occurring; and | What is the current state of knowledge about the likelihood of harm?

Is the likelihood continuous (chronic) or sudden (acute)? Are there uncertainties about the likelihood of the harm? |

| (b) the degree of harm (the consequences) that might result from the hazard or risk; and | What would be the nature and severity of the potential harm?

What is known about harm of that nature and severity? Will harm be immediate or delayed? Is there a possibility of harm to future generations? Is the harm reversible? Are there uncertainties about the magnitude of the harm? What are the expected number and range of harms arising from the hazard? Is the harm common or dread (ie, deeply feared by some people)? Would there be no detectable adverse effect? Are vulnerable groups of the public exposed? |

| (c) what the person concerned knows, or ought reasonably to know, about:

(i) the hazard or risk

(ii) ways of eliminating or minimising the hazard or risk

|

What is the current state of knowledge about the means available to eliminate or minimise the risk?

Are guidance documents on the hazard and associated risks freely available or of restricted access? Is the hazard natural or man-made? What is the exposure relative to natural background? Is the hazard occupational or non-occupational or both? Are the people exposed to the hazard aware of it and any potential harm it might cause (ie, voluntary or involuntary)? Is the hazard familiar or novel? What could reasonably be done to discover new means to eliminate or minimise the risk? Can the hazard (causes of risk) or potential harm (consequences) be eliminated? Can a lesser hazard be substituted for the current hazard, so reducing the risk? Can the hazard be isolated from people? Can people be isolated from the hazard? Can an engineering control be used to minimise the hazard? Can administrative controls be implemented to minimise the risk? If there is still a risk, would personal protective equipment be of any benefit? |

| (d) the availability and suitability of ways to eliminate or minimise the risk | Arising from (c)(ii):

What are the current controls over the risk? What is the effectiveness of those controls? Who manages the controls? Do workers and/or the public have confidence in the quality of that management? Could emergency services cope with any incidents? |

| (e) after assessing the extent of the risk and the available ways of eliminating or minimising the risk, the cost associated with the available ways of eliminating or minimising the risk, including whether the cost is grossly disproportionate to the risk | Could relatively cheap expenditure or modifications significantly reduce risk?

If the workers are mobile or peripatetic, how will new or modified controls work? Will the new or modified controls need to be applied at each workplace?

For “grossly disproportionate” see the discussion of the “value of a statistical life” below.

|

| NZ Companies Act 1993, section 138 and NZ HSWA, section 44 | Do workers and/or the public have confidence in the independence and quality of expert advice?

How is the risk viewed considering prevailing professional practice? |

18.2.2 Reasonable

The section is provided for guidance and stimulation of thought, not as a legal opinion. You should consult your legal advisor if you need legal guidance. It is adapted with additions from Todd, S. (2005). Negligence: Breach of Duty. In Todd, S. (Ed.), The Law of Torts in New Zealand (4th ed., pp. 312-336). Wellington: Brooker’s Ltd. The 7th edition is available online in the university library.

The standard of care for compliance with a duty of care is an abstract formula. It would be impossible for the courts to lay down detailed codes of conduct to cover the whole field of human endeavour. Accordingly, they invented the ubiquitous “reasonable man”. This can be traced back to a mid-19th century case when the judge wrote (Blyth v Birmingham Waterworks, 1856):

Negligence is the omission to do something which a reasonable man, guided upon those considerations which ordinarily regulate the conduct of human affairs, would do or doing something which a prudent and reasonable man would not do.

The standard is therefore that of reasonableness. A person cannot avoid liability by saying “I am an exceptionally stupid, clumsy and accident-prone individual who never learns from experience”. The question is what should have been done, not what could have been done. The law does not consider the weaknesses of an individual but also does not set the bar at the level of the perfect citizen. Thus the courts have sought to capture the reasonable man’s ordinariness. He is the “man in the street”. He has normal intelligence and does, or does not do, what a prudent man would do.

Although the legal standard of care is that of the reasonable and prudent person, the degree of care needed to satisfy the standard is infinitely variable. Great care may be needed or only a little, but there are no “high” or “low” standards. Whether the standard of the reasonable person has been attained must be determined ultimately in the light of what is being done and in what circumstances it is being done. The flexibility of this test means that subjective factors may not be entirely excluded from consideration. Personal characteristics of the defendant, such as an incapacity to cope in unexpected circumstances, sometimes may be considered part of the circumstances. Some key issues to consider include the following.

Ordinary standards

The reasonable person is credited with ordinary intelligence and perception, and with possessing the common knowledge that enables them to appreciate danger and take steps to guard against it. If the defendant has superior knowledge, the conduct is judged by the standard of the reasonable person possessing that knowledge. Special or expert knowledge need not be demonstrated unless the defendant has presented themselves as an expert or has undertaken an activity where specialised knowledge is needed.

Professions and trades

In the case of the especially skilled, the standard of conduct must conform to that which ought to be attained by persons presenting themselves as possessing the relevant skills. Thus, architects, auditors, company directors, lawyers, doctors, engineers, and surveyors all must exhibit the care reasonably expected of skilled and informed members of their respective professions, judged as at the time the work was done [these words are of increasing importance to OHS professionals as we gain more and higher qualifications]. The standard of care expected of persons in trade or business is determined in a similar fashion.

An “error of judgement” may be completely consistent with the due exercise of professional skill but might also be glaringly below proper standards. A professional in the exercise of their professional judgement should be able to show why they took an action or gave specific advice.

A professional who purports to be an expert in a specific area must act as a reasonable professional possessing expertise in that area. Lack of skill or experience is no defence if the task in hand demands greater knowledge or experience, but whether additional specialist advice or assistance is needed is a question of fact. If specialist advice is needed the defendant is negligent if they do not obtain it. In a District Court case (WorkSafe NZ v Precision Animal Supplements Ltd, 2018b) an OHS consultant was fortunate not to be prosecuted for a breach of section 45(b) of the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015.

Generally, a person who does call in a reputable expert or specialist has taken reasonable care and is not responsible for any shortcomings on the part of the expert. For example, a building owner may not be liable for a defect in a lift if they have engaged a competent lift engineer to inspect and maintain it. However, a person may be under a non-delegable duty to take care if (a) they are in a position of control, (b) they engage another person to do work on their land or allow another person to do work on their land, and (c) the plaintiff is dependent on the defendant or is particularly vulnerable to the danger. The defendant’s duty in these cases is to ensure that care is taken. The ultimate issue is what reasonable care is required in all the circumstances of the case.

Cost of a precaution as part of reasonableness is considered in section 18.2.6.

18.2.3 Recklessness

Proving that a PCBU or individual worker was reckless (ie, in breach of section 47 HSWA) may be difficult as was found when Waste Management NZ Ltd successfully appealed its conviction (Alcom, 2022; Nicholson & Wray, 2024; Waste Management NZ Ltd v WorkSafe NZ, 2021).

18.2.4 English common law

In an English common law case Lord Reid wrote (Marshall vs Gotham Co Ltd, 1954):

If a precaution is practicable it must be taken unless in the whole circumstances that would be unreasonable. And as men’s lives may be at stake it should not lightly be held that to take a practicable precaution is unreasonable.

In another English common law case (Edwards v NCB 1949) Lord Asquith said:

“Reasonably practicable” is a narrower term than “physically possible” and it seems to me to imply that a computation must be made by the owner, in which the quantum of risk is placed on one scale and the sacrifice involved in the measures necessary for averting the risk (whether in money, time or trouble) is placed in the other; and that if it be shown that there is a gross disproportion between them – the risk being insignificant in relation to the sacrifice – the defendants discharge the onus on them. Moreover, this computation falls to be made by the owner at a point of time anterior to the accident.

(Edwards v National Coal Board (1949) 1 KB 704 at 712, CA per Asquith L: J.)

In the same case, another judge said:

This shows that in every case it is the risk that has to be weighed against the measures necessary to eliminate the risk. The greater the risk, no doubt, the less will be the weight to be given to the factor of cost.

(Edwards v National Coal Board (1949) 1 KB 704 at 712, CA per Tucker L: J.)

This decision means a PCBU must consider the consequences and their likelihood before any harm has occurred.

Sometimes it will be evident such consequences are not acceptable or tolerable “as is” and must be eliminated or minimised. Other risks require action to modify them so that they become acceptable. They are in a region often referred to as the “as low as is reasonably practicable” or tolerability region. In this region a risk is only tolerated if it gives some benefit: when workers could be killed or injured such circumstances are rare.

One major problem with the SFAIRP test is that decision-makers may not be the people exposed to harm.

Many health- or safety-related risks will be broadly acceptable and there will be no need for detailed working to demonstrate they have been reduced SFAIRP. However, the risks still need monitoring to give assurance they remain at this level.

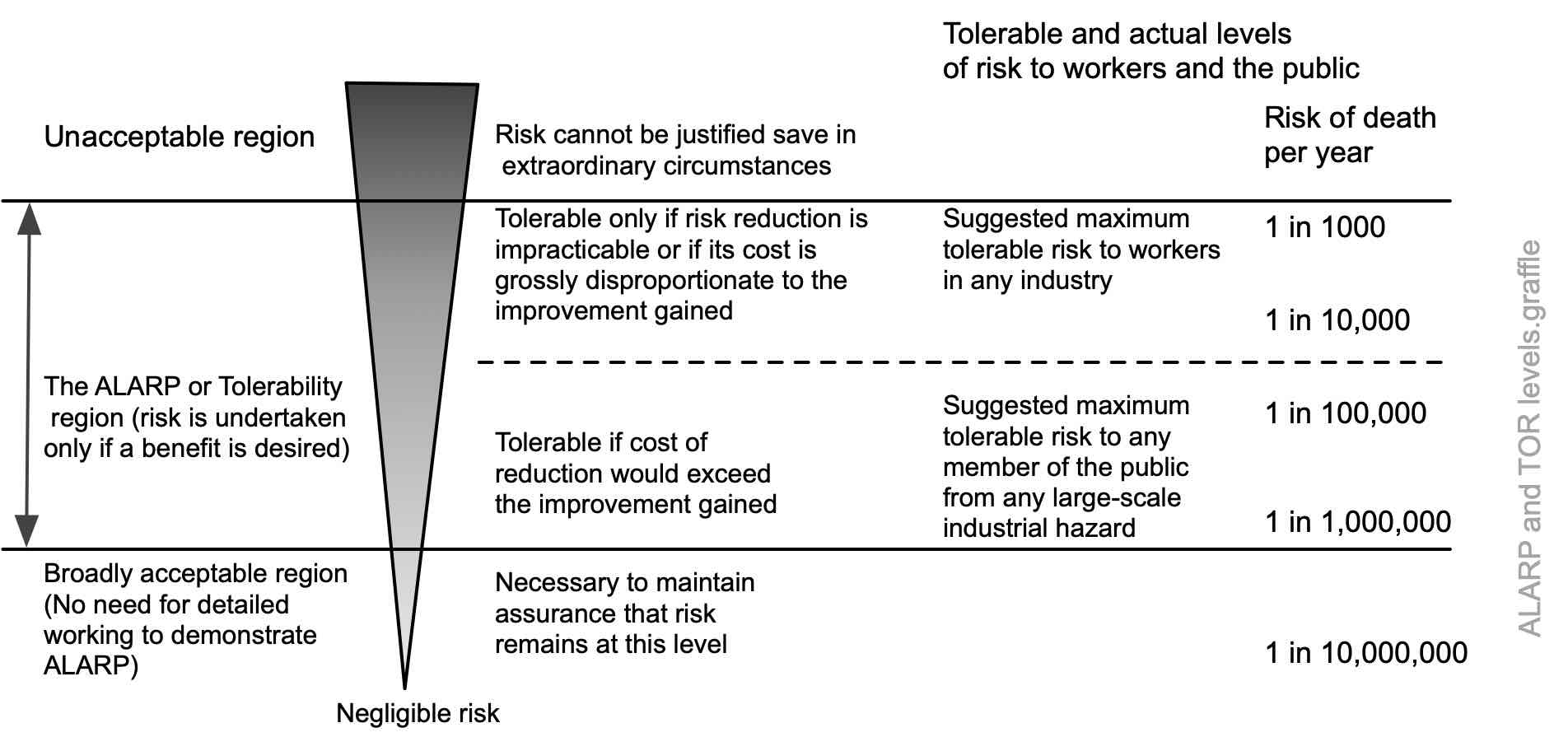

Three broad levels of risk are summarised in Figure 55, adapted from an important British Health and Safety Executive publications, Reducing Risk, Protecting People (HSE, 2001, available online free from the UK HSE website).

Source: Reproduced from HSE (2001)

The diagram shows two horizontal solid lines and a horizontal dotted line.

- Above the upper solid line is the unacceptable region where “risk cannot be justified save in extraordinary circumstances”. In this region the activity giving rise to risk must be stopped or so modified that the risk becomes at least tolerable.

- The ALARP or tolerability region is between the two solid lines. In this region, risk is tolerable only if risk reduction is impracticable or if the cost of modification is grossly disproportionate to the improvement gained. In other words, the onus is on the risk owner to find practicable and reasonable ways of modifying the risk. HSE suggested a maximum tolerable risk of death for workers in any industry of 1 in 1000 per year.

- For members of the public, risks of being killed by some large-scale work activity should not exceed 1 in 100,000 per year for an existing installation, or 1 in 1 million (often expressed as 10-6) for a new installation. For workers, a level of risk of 10-6 is also taken as acceptable and requires no further action other than maintenance of existing controls.

- Below the lower solid line, risks are generally broadly acceptable. However, the risk owner must “maintain assurance that risk remains at this level”.

The HSE also recognises there will be “negligible risk” from some work activities and suggests these equate to a risk of death of 1 in 10 million per year (approximately the annual level of risk for death by lightning strike in New Zealand).

18.2.5 What if an event could result in multiple deaths?

Many authors have discussed the problem of multiple-fatality events. The quotation below from Griffiths (1981b, pp. 67-69) sets out the problem clearly. The intervening 45 years have not resolved the problem.

There must be few discussions on risk that do not make reference to multiple-fatality accidents as a topic of special concern. The problem has often been encapsulated in statements to the effect that society is prepared to tolerate a heavy annual death toll if the incidents involve only one or two deaths at a time, but special concern surrounds events in which many deaths are suffered simultaneously. Looked at from the point of view of the average death rate the accident that takes 100 lives once every 10 years is the same as 100 single deaths spread over 10 years, but the former case appears to generate much greater concern about the risks involved. This problem raises the question of how life is valued. Wilson (1975) places a value on this concern and assumes that ‘a risk involving N people simultaneously is N2 (not N) times as important as an accident involving one person.’ There is no compelling reason to accept this particular arbitrarily chosen weighting, but one can point to reasons why simultaneous fatalities should be regarded with greater concern, eg:

(a) If the deaths occur at one time then the immediate social impact on families involves many people simultaneously, thus making the scale of the loss appear more significant against the steadier background of smaller events.

(b) If the victims are all drawn from one community then the impact is less readily absorbed than if many separate groups were involved.

(c) If the deaths occur all in one place then the scale of the loss is more apparent than otherwise (it is conceivable that a single incident could lead to many delayed deaths in diverse locations).

(d) If the deaths are all attributable to one event then there will be understandable concern that one mistake or one fault should have such large consequences. However, it is notable that this may not necessarily apply if the deaths are attributable only to one kind of activity, eg, consider the apparent acceptability of 7000 deaths a year in the UK from motoring accidents.

On the basis of such considerations one may argue that diversity of geographical or community origins of the victims would increase the acceptability of a given multiple-fatality event. For example, most aircraft accidents would involve people from many diverse groups, whereas a dam failure would involve a more localised group of communities. Whatever the outcome of such considerations may be, it seems that there is an emerging recognition that some weighting needs to be introduced in risk criteria to express this non-reciprocity between frequency and magnitude of consequences and that a line of equal ƒN product may not be an appropriate form of criterion for early deaths.

18.2.6 Value of a statistical life

In personal injury cases an economic equation poses a distasteful comparison between the material cost of avoidance and the value of a person’s health or life. An economic analysis is more easily made in cases of property damage or financial loss. The following notes are only an introduction to the concept of valuation of statistical lives for risk management purposes.

When developing risk criteria, it may be necessary to compare different types of risk. For risks with financial consequences, it should be straightforward to measure what is at risk. However, how do we compare the value of people, the natural environment, cultural artefacts, and reputation? Can we value the life of a person? Is a baby worth more than an 80-year-old? Should we spend $10 million to prevent the death of one passenger in a train crash on a commuter train or $1 million in foreign aid to prevent the deaths of many children due to malnutrition in a developing country? In policy making, and common law terms, how much would it be reasonable to spend to prevent a death or injury?

It is sometimes necessary to weigh the costs of a risk treatment against the benefits it will create (Clough, 2023; Fischer, 2016). For risks with health and safety-related consequences, we need to show that what is to be spent will achieve a commensurate benefit. While the costs are relatively easy to calculate, the benefits in life safety terms are more complex and subject to debate.

Policymakers and decision-makers need such estimates if they are to fairly allocate scarce resources. Such calculations may seem cold and cynical, but they are needed if we are to use limited resources wisely. However, we should also keep in mind that such risk decisions can drive change in technology.

The approach suggested here, and the data below, align with that used by the British Health and Safety Executive in its report Reducing Risk, Protecting People (HSE, 2001) and is useful when deciding if practicable steps to ensure the health and safety of people would be reasonable, and not grossly disproportionate.

An assessment could be done to determine the chance of injuring an actual person, taking full account of the nature, extent, and circumstances of the exposure. However, there are generally three problems that limit the usefulness of such an approach for managing risks.

- Ethical and legal requirements mean that we cannot wait for people to be exposed to harm before taking decisions about whether the chance of harm should be incurred at all, or the degree to which it should be controlled.

- The actual-person approach could be very resource intensive; exposure to most hazards is seldom confined to one person and it would be necessary to carry out an assessment for each person exposed (individuals are affected differently by risks depending, amongst other things, on their physical make-up, abilities, age, and the circumstances giving rise to their exposure).

- It would be very difficult to extract and distil useful information from all the individual assessments.

Value of a statistical life

In practice therefore, assessment of the risks to an actual person has rather limited uses. The more common alternative is to perform the assessment in relation to a “hypothetical person” – a statistical life – and calculate the value of a statistical life (VOSL). The term “hypothetical person” describes an individual who is in some fixed relation to the risk, eg, the person most exposed to it, or a person living at some fixed point or with some assumed pattern of life. To ensure that all significant risks for a particular hazard are adequately covered, there will usually have to be several hypothetical persons constructed. Some of these issues have been explored in grey literature and articles (eg, Binch & Bell, 2007; Chapple, 2020; Chilton et al., 1998; Fischer, 2016; Lower et al., 2013; O’Dea & Wren, 2012; Pathak, 2008).

The value of a statistical life concept is controversial. It is based on a “willingness to pay” approach when, in fact, people may be willing to pay more for some risk treatments (such as cancer prevention) than for others.

The Ministry of Transport (MoT 2024) revised the social cost of road crashes per fatality alone to $14.2 million for 2023. Data from the most recent MoT update report is shown in Table 33. See also Miller et al (2022) for work in this area, and Clough (2023) for commentary on the increases introduced by the MoT in 2023.

Table 33. Average social cost per crash and per injury, by cost component for 2024

|

Average cost per crash for all roads ($) |

||||

| Component | Fatal crash | Serious injury crash | Minor injury crash | Non-injury crash |

| Loss of life/permanent disability | $16,024,200.00 | $853,600.00 | $94,500.00 | $0.00 |

| Loss of output | $1,100.00 | $2,700.00 | $500.00 | $0.00 |

| Medical | $16,400.00 | $20,500.00 | $1,300.00 | $0.00 |

| Legal and court | $38,900.00 | $4,400.00 | $1,600.00 | $100.00 |

| Vehicle damage | $14,600.00 | $9,300.00 | $7,500.00 | $3,700.00 |

| Total | $16,095,200.00 | $890,500.00 | $105,400.00 | $3,800.00 |

|

Average cost per injury for all roads ($) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Fatality | Serious injury | Minor injury | |

| Loss of life/permanent disability | $14,215,300.00 | $739,200.00 | $78,200.00 | |

| Loss of output | $0.00 | $2,300.00 | $400.00 | |

| Medical | $8,100.00 | $18,000.00 | $1,100.00 | |

| Legal and court | $33,600.00 | $3,500.00 | $1,300.00 | |

| Vehicle damage | $8,600.00 | $6,400.00 | $6,200.00 | |

| Total | $14,265,600.00 | $769,400.00 | $87,200.00 | |

The average cost per fatal crash $16 million suggests we should be willing to spend that amount to prevent one fatality.

Two New Zealand cases and Pike River

In an appeal to the High Court (Martin Simmons Air Conditioning Services Ltd v Dept. of Labour, 2008) it was found that provision of a “cherry picker” (a small mobile elevating work platform) would have been a practicable precaution to prevent the victim falling though a fragile roof and the cost (about $240 at the time) would have been reasonable even though the contractor might not have been awarded the job on price grounds.

In a case heard under the Health and Safety in Employment Act 1992 (WorkSafe NZ v Ministry of Social Development 2016) Chief District Court Judge Doogue considered the availability and cost of the means to have prevented a violent client from being able to attack and murder Ministry workers. The judge considered that costs of $50,000-$180,000 would not be grossly disproportionate to prevent such harm at one site. This scaled up to a nationwide cost of between $13.1 and $27.3 million. If using a VOSL of $5 million per person, the scaled-up costs would pay for the protection of between 2.3 and 5.7 workers.

Finally, it is known that the ventilation system in the Pike River mine needed to be commissioned or replaced with a likely cost of $2 million. This would have paid for the protection of the 30 men usually on a shift from a methane gas fire or explosion.

18.2.7 Due diligence

The due diligence defence is found in a range of legislation. It allows a business or undertaking to avoid conviction if it can show it used due diligence to comply with the Act in question.

In an important English case (Tesco Supermarkets Ltd v Nattrass, 1971) heard on appeal in the House of Lords, the Law Lords decided that a board may delegate responsibilities for compliance to managers but a business or undertaking cannot use the due diligence defence unless it can demonstrate there was a compliance system in place at the time of the alleged offence. This may require an audit programme as well as a management system.

See section 44 of the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 setting out due diligence requirements for “officers” of a business or undertaking as discussed in Peace et al. (2017).

18.2.8 Offence of reckless conduct in respect of duty

Section 47(1), HSWA states:

A person commits an offence against this section if the person:

(a) has a duty under subpart 2 or 3; and

(b) without reasonable excuse, engages in conduct that exposes any individual to whom that duty is owed to a risk of death or serious injury or serious illness; and

(c) is reckless as to the risk to an individual of death or serious injury or serious illness.

Section 47 also sets out the penalties for an offence against subsection 1 clearly showing that reckless conduct is viewed more seriously than negligently causing such harm (section 48) or simply failing to comply with a duty (section 49). But what is reckless conduct?

In an article by France (1988) the concept of recklessness was reviewed and, at page 147 quoted a UK case where it was described as “recognising a risk and running it in circumstances where to do so was unreasonable”. The Concise Oxford English Dictionary (2022) defines reckless to mean “without thought or care for the consequences of an action”.

Download a copy of the Crimes Act 1961, search for “reckless”, and read sections 167 and 250. How does section 167 define murder? And, given the high level of computer-controlled systems in many workplaces, could reckless behaviour endanger many people both on and offsite – see section 250.

For other cases on recklessness see Anon (2017, a UK case), Selinger (2018, an Australian case) and Alcom (2022, a New Zealand case). Alcom shows the difficulty of proving recklessness.

18.3 Chapter summary

This chapter has outlined legal requirements to judge whether risk is acceptable before any harm has occurred. Such judgements can sometimes be very difficult and may require a PCBU to err on the side of caution, that is, to be very careful. Judging the cost of treatments – new or upgraded controls – may seem expensive but might be found to not be grossly disproportionate in court.

18.4 References used in this chapter

Alcom, B. (2022). Health & Safety prosecution: when will a defendant be ‘reckless’? [Web report]. Lexology, https://www.lexology.com/

Anon. (2017). “Reckless” businessman jailed following factory roof death. Safety & Health Practitioner. https://www.shponline.co.uk/news/reckless-businessman-jailed-following-factory-roof-death/

Binch, S., & Bell, J. (2007). The cost of non-injury accidents: scoping study [Research Report RR0585]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Blyth v Birmingham Waterworks [1856].

Chapple, S. (2020). Covid-19: How much is a NZ life worth? Newsroom. https://www.newsroom.co.nz/2020/03/17/1087345/how-much-is-a-nz-life-worth

Chilton, S., Jones-Lee, M., Loomes, G., et al. (1998). Valuing health and safety controls [Contract Research Report CRR171]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Clough, P. (2023). The value of safety improvements [Research Report 107-2023]. NZIER, Wellington. https://www.nzier.org.nz/

Cribby, P. (2023). Safety is not a company’s first priority: Myths & Misconceptions in OSH Management. Professional Safety, 68(10), 45-47.

Fischer, S. (2016, 22 October). What are you worth? New Scientist, (3096), 28-33. http://www.newscientist.com/

France, S. (1988). A reckless approach to liability. Law review (Victoria University of Wellington), 18(2), 141-153.

Griffiths, R. (1981). Introduction: The nature of risk assessment. In R. Griffiths (Ed.), Dealing with Risk: The Planning, Management and Acceptability of Technological Risk (pp. 1-20). Manchester University Press.

Griffiths, R. (1994). Discounting of delayed versus early mortality in societal risk criteria. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries, 7(5), 432-438. https://doi.org/10.1016/0950-4230(94)80062-6

HSE. (1992). The Tolerability Of Risk From Nuclear Power Stations. HSE Books,.

HSE. (2001). Reducing risks, protecting people. HSE Books, Sudbury. http://www.hse.gov.uk/

ISO31000: 2009 Risk management – Principles and guidelines, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

ISO31000: 2018 Risk management – Guidelines, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

ISO31073: 2022 Risk management — Vocabulary, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

ISO45001: 2018 Occupational health and safety management systems: Requirements with guidance for use, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

Lower, A., Pollock, K., & Herde, E. (2013, 2013/04/01). Australian quad bike fatalities: what is the economic cost? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 37(2), 173-178. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12036

Lowrance, W. (1976). Of Acceptable Risk: Science and the Determination of Safety. Harvard University.

Marshall vs Gotham Co Ltd [1954] House of Lords. http://www.safetyphoto.co.uk/subsite/case%20m%20n%20o%20p/marshall_v_gotham_co_ltd.htm

Martin Simmons Air Conditioning Services Ltd v Dept. of Labour [2008] Auckland High Court.

Miller, G. F., Barnett, S. B., Wulz, A. R., et al. (2022). Costs attributable to criminal justice involvement in injuries: a systematic review. Injury Prevention, ip-2022-044756. https://doi.org/10.1136/ip-2022-044756

Ministry of Transport. (2024). Social cost of road crashes and injuries. Author, Wellington. https://www.transport.govt.nz/

O’Dea, D., & Wren, J. (2012). New Zealand Estimates of the Total Social and Economic Cost of Injuries. For All Injuries, and the Six Injury priority areas. For Each of Years 2007 to 2010. In June 2010 dollars. [Research Report wpc133825]. Wellington. http://www.acc.co.nz/

Concise Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press Ltd. (2022).

Pathak, M. (2008). The costs to employers in Britain of workplace injuries and work-related ill health in 2005/06 [Discussion Paper 002]. Health and Safety Executive, Sudbury.

Peace, C., Mabin, V., & Cordery, C. (2017). Due diligence: a panacea for health and safety risk governance? Policy and Practice in Health and Safety, 15(1), 19-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/14773996.2016.1275497

Selinger, M. (2018). Reckless safety breaches under the spotlight. Lexology. Retrieved 24 May 2018 from https://www.lexology.com/

Tesco Supermarkets Ltd v Nattrass [1971]. http://swarb.co.uk/tesco-supermarkets-ltd-v-nattrass-HL-31-Mar-1971/

Wilson, R. (1975). The costs of safety. New Scientist, 68, 274-275.

WorkSafe NZ. (2016). Reasonably Practicable [Fact Sheet WSNZ_2191_Mar 16]. Author, Wellington. http://www.worksafe.govt.nz/

WorkSafe NZ v Ministry of Social Development [2016] NZDC 24649 Ashburton District Court. https://www.districtcourts.govt.nz/

WorkSafe NZ v Precision Animal Supplements Ltd [2018b] NZDC 19342 Ashburton District Court. https://www.districtcourts.govt.nz/