13 Risk assessment process: scope, objectives, engagement

13.1 Chapter overview

Cross reference to clauses 5.2 and 5.3, ISO31000 (2009), clause 6.3 ISO31000 (2018) and clause 4.2 Annex SL.

Check for key readings, webinars, and videos for complementary resources.

Definitions of italicised terms are in the Glossary.

Relevant law

- Health and Safety at Work Act 2015

- Health and Safety at Work (Worker Engagement, Participation, and Representation) Regulations 2016

Key questions

What is or will be the impact of artificial intelligence on the business?

If risk is the “effect of uncertainty on objectives”:

- what are the objectives of the organisation, activity, system, or item?

- how widely should the scope of the assessment be set?

- how widely should engagement be carried out?

- what uncertainties could affect achievement of the engagement?

Useful management techniques

- 5W1H to identify stakeholders (see section 21.3.1)

- Brainstorming (see section 21.3.4)

- Engagement, communication, and consultation process (see section 21.3.9)

- Interviews (see section 21.3.19)

- Literature or document review to understand internal, external, and wider issues (see section 21.3.22)

13.2 Scope for the assessment activity

Risk assessment is defined as the “overall process of risk identification, risk analysis and risk evaluation”. As previously, substitute in the definition of risk to give: “overall process of identification of objectives and the effects of uncertainties that could affect them, analysis of the uncertainties and evaluation of the acceptability of those effects”.

It is usual to set terms of reference for an assessment or any kind of investigation. That may require asking stakeholders for information, their opinions or guidance.

The scope of an assessment activity must be clearly stated. For a major assessment or a change in the management system the work may take weeks or months and require substantial resources. An assessment of operational risk may require less resources but also needs clear terms of reference and adequate resources.

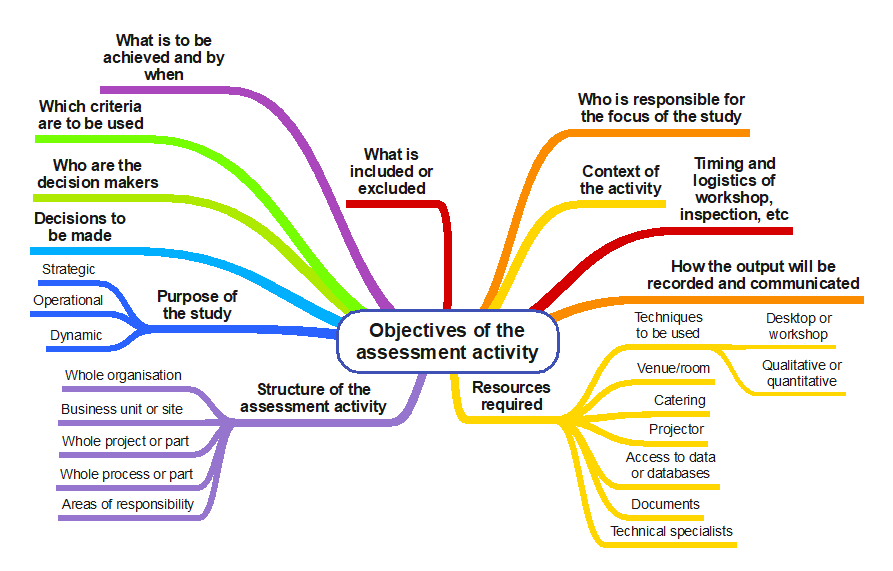

The following diagram summarises some of the issues to be considered.

13.3 Organisational objectives

- What are the objectives of the organisation, activity, system, or item?

- Cross reference to clauses 4.1 and 6.2 in management system standards.

Development of objectives

Until the late 1940s, it seems that management theorists regarded objectives as “known, obvious and given” that were somehow used “as a foundation for … planning, or at least inherent in … planning”(Drucker, 1973). Drucker worked with others to develop a range of management concepts and is often credited with developing “management by objectives” (MBO) (Greenwood, 1981)although it seems more likely he was the first to publicly use the phrase and elaborate on the concept.

Drucker argued that objectives are risk-taking decisions that are anything but known or given, and that objectives needed to be explicitly stated; that is, objectives are something that need to be set before it is possible to undertake planning. He also helped develop the “manager’s letter”, a form of contract between a manager and their superior that set out the goals, activities, and standards to be achieved in the next month; these were aligned with organisation objectives. Crucially, the letter was developed by the person who would achieve the objectives, not their manager.

If we substitute in “effect of uncertainty on objectives” we can see that junior managers should be capable of managing day-to-day uncertainties that might affect their objectives. Similarly, executive managers will be concerned with high-level objectives and wider uncertainties.

But what is an objective?

Risk is the “effect of uncertainty on objectives” and objective is the “result to be achieved” (ISO/IEC Annex SL, 2020). If risks are to be managed, it is essential to know and understand the objectives of the organisation. This part of the course handbook deals with identification of objectives to help answer the questions:

Notes to the definition of objectives (ISO31073, 2022) have been adapted to create Table 13 below to help analyse organisation objectives. OTIF means On Time In Full. For example, OTIF 95% means that (considering all orders) at least 95% should be delivered on time, complete in one shipment, to the right location, complying with all specifications including quality control. OTIF is a common key performance indicator (KPI) for quality.

Objectives can have different aspects such as financial, health and safety, and environmental goals and can apply at different levels such as strategic, organisation-wide, project, product, and process.

- All objectives should be Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Time-bound (SMART) (Bjerke & Renger, 2017).

- Strategic objectives might be couched in terms of, for example, an increase in market share of 25% within five years.

- Organisation-wide objectives might include, for example, a 10% reduction per year in waste.

- Projects need a clearly stated objective in terms of money, time, and deliverables.

- Processes (and associated procedures such as “standard operating procedures” for their achievement) also need clear objectives.

- It is also possible to define objectives in terms of system intent. For example, the system intent of a tank is to hold the contents while they are processed or until they are required elsewhere in the system.

- There can be a “cascade” of objectives within an organisation, with each manager making their individual contributions to overall organisation objectives.

Table 13 can be used to help identify organisational objectives. note that on time, in full 95% of the time can be quite difficult to achieve consistently.

Table 13. Identification of objectives template

| Financial | Operational | Customer service | Compliance obligations | Health and safety | Environmental | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategic or organisation wide | ||||||

| Project, including an audit | ||||||

| Product | OTIF 95% = on time, in full 95% of the time | |||||

| Process or activity | ||||||

| System or item |

In the table:

Process is a: “set of interrelated or interacting activities which transforms inputs into outputs(ISO/IEC Annex SL, 2020).

Activity: “an action taken in pursuit of an objective” (Oxford University Press Ltd, 2022)

Item is: “any part, component, device, subsystem, functional unit, equipment or system that can be individually described” (IEC 60300.1, 2015)

System is a: “set of interrelated items that collectively fulfil a requirement” (IEC60300)

Note 1: A system is considered to have a defined real or abstract boundary.

Note 2: External resources (from outside the system boundary) may be required for the system to operate.

Note 3: A system structure may be hierarchical, eg, system, subsystem, component, etc.

13.4 Engagement, communication and consultation

13.4.1 What is engagement?

Social Exchange Theory is one theory of worker engagement; it is simple and intuitive and proposes that we are hard-wired to repay our social debts. If we receive another person’s kindness, we feel some obligation to repay it. However, other research suggests that worker engagement will not produce its potential benefits if limited to one objective. The best results may come from engagement of contractors, sub-contractors, suppliers, and customers with the objectives of improving occupational safety and health, quality, and environmental protection. Interestingly, this was the model on which Toyota built its growth and reputation. The following table sets out some key engagement issues in a maturity model (Nickleby HFE, 2002) format.

Table 14. Stakeholder engagement

|

Attribute |

Novice |

Competent |

Proficient |

Expert |

| Engagement with stakeholders on risk | Practices include:

basic written and verbal communication little or no involvement in decision making compliance is patchy at best Workers are concerned about being blamed |

Practices include novice engagement plus engagement:

includes consultation uses pre-task briefings to discuss risks and to coordinate activities involves stakeholders in risk assessments uses suggestion schemes uses hazard-reporting schemes only uses inspections and audits just to look for unsafe conditions may be limited to one area or activity (eg, health and safety) aims for good levels of compliance |

Practices include the competent practices plus engagement:

addresses physical and social work environment uses inspections and audits to probe the quality of working relationships and conditions develops the culture of management and workers are “in it together” uses above average investment in competent internal safety advisors uses numerous sources and channels of communication aims for high levels of compliance |

Practices include the proficient practices plus engagement:

runs across the whole organisation addresses the determinants of individual risk-taking behaviour uses informal approaches by management rather than formal or written approaches uses numerous sources and channels of communication uses active reporting of non-compliances without fear of blame |

| Safety-related engagement | Workers and contractors have basic working conditions (pay, resources, etc) and do what they are paid for with no thought given to reciprocation | Workers and contractors have reasonable working conditions but only do the minimum in risk-related meetings

Only a few desirable behaviours are captured |

The organisation consistently demonstrates it cares about workers, contractors, and other stakeholders

|

There is above average investment in competent internal risk and safety advisors |

| Quality of reporting to stakeholders | None or little | Routine non-filtered analysis of data | Managed and focused reporting, including lessons learned from events | Feedback gives incentives for continued improvement

Feedback helps drive actions to change root causes in the internal and external contexts |

Benefits of “expert” engagement

Benefits of “expert” engagement have been reported to include (Cameron et al., 2007; Cheyne et al., 2012; Healey & Sugden, 2012; Lunt et al., 2008):

- reduced turnover and absenteeism

- performance of core duties to a higher standard

- workers seeking proactive and discretionary ways of supporting the organisation

- workers less likely to “walk away” from a hazard or problem

- workers volunteering to do more and give more information

- facilitation of new working methods (eg, self-managed teams)

- improved communication between projects when there might be competition for resources

- improved organisation reputation and ability to attract quality employees

- improved customer satisfaction

- better ratings by insurers.

13.4.2 Legal requirements for engagement under HSWA

Read the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 sections 34, and 58-60, and the Health and Safety at Work (Worker Engagement, Participation, and Representation) Regulations 2016.

How widely should these requirements be interpreted? Also read section 36(3)(f) and the requirement for the provision of information as part of communication. How does the concept of “informed consent” (Faden et al., 1986, pp. 274-275) influence these requirements, especially for “other persons” to whom a service is being delivered? For example, participants in adventure activities?

13.4.3 Interested party or stakeholder?

International standards have recently moved to use the term “interested party” instead of “stakeholder”, (ISO/IEC Annex SL, 2020) possibly as a result of lobbying in one of the ISO technical committees, but the two terms have the same definitions.

13.4.4 Communication and consultation about uncertainty

What is consultation?

In a civil case about airport landing charges, Cooke J wrote (Wellington International Airport Ltd v Air New Zealand, 1993):

The word “consultation” did not require that there be agreement as to the charges nor did it necessarily involve negotiations towards an agreement, although this might occur particularly as the tendency in consultation was at least to seek consensus. It clearly required more than mere prior notification. If a party having the power to make a decision after consultation held meetings with the parties it was required to consult, provided those parties with relevant information and with such further information as they requested, entered the meetings with an open mind, took due notice of what was said and waited until they had had their say before making a decision: then the decision was properly described as having been made after consultation.

Research into best practice risk communication

Research into effective risk communication led to the following recommendations (Gervais, 2007):

- formulate a communication plan

- coordinate outward bound risk communications

- use a variety of communication methods (eg, face-to-face, networking, partnerships)

- incorporate cultural nuances

- use intermediaries who are prominent in a target community

- maintain links with established contacts

- use sector-specific information

- use plain language

- establish a review process.

Risk and crisis communication best practice

The list below outlines those practices regarded as best for risk and crisis communication.

Partnerships with and listening to stakeholders

-

- Build relationships prior to crises.

- Collaborate and coordinate with credible sources.

- Understand audience interdependencies.

- Listen to people’s concerns and understand the audience.

Messaging, messages, and the media

-

- Include actionable steps to motivate action.

- Communicate with honesty, candour, and openness.

- Plan messages prior to crises.

- Meet the needs of the media (eg, deadlines for publishing or broadcasting) and remain accessible.

- Communicate with compassion, empathy, and concern.

- Include media in pre-event planning and relationship building.

- Sell risk communication as an everyday practice.

- Address emphasis on fear to overcome public’s apathy about risk/crisis perception.

- Accept uncertainly and ambiguity because risk and crisis situations evolve and change over time.

13.4.5 Communication and consultation process

See section 21.3.9 for a generic process for engagement, communication and consultation and any specific requirements for engagement.

First be clear which activity the engagement will support and then define the objectives of the engagement.

Using the generic process, identify the stakeholders in the activity, project, or risk. Stakeholders may be identified when developing the context statement, but you may need to start from first principles. This might be done using the 5W1H mind map in (section 21.3.9) in a brainstorming session with colleagues or in a more formal workshop.

Three tables are shown in section 21.3.9. The top table can be used to record the stakeholders, their importance/influence rating and outline engagement plan. Keep in mind this may be sensitive information and, in the state sector, a stakeholder may ask for such information under the Official Information Act. The table can be expanded to record as many stakeholders as you need to engage with.

The middle table is then used to analyse the stakeholders for their importance and influence in the activity, project, or risk. You will then need to develop a plan for engagement with the stakeholders. If there are two or more distinct groups of stakeholders, you may need two or more plans. Some stakeholders may only need to be communicated with. Others may need to be consulted. Some may need to be both communicated and consulted with. Make sure your plan addresses your stakeholders’ needs.

Some engagement techniques are summarised in the third table. Different approaches are likely to be needed for different stakeholders and a combination of approaches is likely to be most effective, especially for key stakeholders.

Communications policy

Policies on external and internal communications relevant to the management system should be established (ISO31000, 2009, paragraph 4.3.1; 2018, paragraph 5.4.5; ISO/IEC Annex SL, 2020, paragraph 7.4). When writing communications use plain English and aim for a reading age of about 12 years. Your readers will understand and respond more quickly to what you have written. If you have colleagues whose job is dealing with communication or consultation, ask for their help.

13.4.6 Other issues

Beware “groupthink” when consulting groups of people (Janis, 1982). There may be one person in a group who has vital information but who is prevented from speaking because the group is searching for a consensus, because of cultural reticence.

A management system must include documented information necessary for the effectiveness of the system, and mechanisms for the control of key documents (ISO/IEC Annex SL, 2020, paragraph 7.5). ISO has published Guidance on Documented Information for Quality Management Systems that has wider application and is available free at https://www.iso.org/directives-and-policies.html.

13.5 Chapter summary

This chapter has introduced scope, objectives and engagement. Use the mind map of risk management activities to help identify what needs to be done to set up a major assessment of uncertainties and their effects on objectives.

Identify and understand the objectives already set for OHS in the PCBU.

Use the generic process for engagement to help identify and understand the expectations and values of stakeholders.

13.6 References used in this chapter

Bjerke, M. B., & Renger, R. (2017). Being smart about writing SMART objectives. Evaluation and Program Planning, 61, 125-127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.12.009

Cameron, I., Hare, W., & Duff, R. (2007). Superior safety performance: OSH personnel and safety performance in construction [Research Report 07.01]. IOSH Publishing Ltd, Leicester. http://www.iosh.co.uk/safetyperform

Cheyne, A., Hartley, R., Gibb, A., et al. (2012). Talk the talk – walk the walk: An evaluation of Olympic Park safety initiatives and communication [Research Report 12.1]. IOSH Publishing Ltd, Wigston. http://www.iosh.co.uk/olympicpark

Concise Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press Ltd. (2022).

Drucker, P. (1973). Management: tasks, responsibilities, practices. Harper & Row.

Faden, R., Beauchamp, T., & King, N. (1986). A history and theory of informed consent. Oxford University Press.

Gervais, R. (2007). Effective Communication: The People, The Message and The Media [Research Report HSL/2007/35]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Greenwood, R. C. (1981). Management by Objectives: As Developed by Peter Drucker, Assisted by Harold Smiddy. Academy of Management Review, 6(2), 225-230.

Healey, N., & Sugden, C. (2012). Safety culture on the Olympic Park [Research Report RR0942]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

IEC 60300.1: 2015 Dependability management – Part 1: Guidance for management and application, International Electrotechnical Commission,, Geneva.

ISO31000: 2009 Risk management – Principles and guidelines, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

ISO31000: 2018 Risk management – Guidelines, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

ISO31073: 2022 Risk management — Vocabulary, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

ISO/IEC Annex SL. (2020). Proposals for management system standards. In Directives, Part 1: Consolidated ISO Supplement – Procedures specific to ISO (11th ed.). International Standards Organization. https://www.iso.org/directives-and-policies.html

Janis, I. L. (1982). Victims of Groupthink: A psychological study of foreign-policy decisions and fiascoes (2nd ed.). Houghton Mifflin.

Lunt, J., Bates, S., Bennett, V., et al. (2008). Behaviour change and worker engagement practices within the construction sector [Research Report RR0660]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Nickleby HFE. (2002). Framework for assessing human factor capability [Research Report OFT016]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Wellington International Airport Ltd v Air New Zealand [1993] 1 NZLR 671 Wellington Court of Appeal.