11 Hazard, risk, and uncertainty

11.1 Chapter overview

Cross reference to ISO31000 clause 6.3 and Annex SL clauses 6.1 and 8.1.

Check for key readings, webinars, and videos for complementary resources.

Definitions of italicised terms are in the Glossary.

Relevant law

- Health and Safety at Work Act 2015

- Health and Safety at Work (General Risk and Workplace Management) Regulations 2016

- Health and Safety at Work (Worker Engagement, Participation, and Representation) Regulations 2016

- Health and Safety at Work (Major Hazard Facilities) Regulations 2016

Key questions

What is or will be the impact of artificial intelligence on the business?

If risk is the “effect of uncertainty on objectives”:

- what are the high-level and operational objectives of the organisation, activity, system, or item?

- what uncertainties could affect achievement of those objectives?

- how widely should the scope of the risk assessment be set?

Useful management techniques

Interviews (see section 21.3.19)

Inspections (see section 21.3.18)

Literature or document review (see section 21.3.22)

Links with management system standards, ISO31000 and SafePlus

See ISO management system standards (section 2.2.1) and SafePlus requirements (section 2.2.5).

Readings and resources

Check the library of webinars, interviews, and videos for complementary resources.

Guidance on occupational health risk assessments for the mining and metals sector has been published by the International Council on Mining and Metals .

11.2 Hazard and risk

Hazard and risk are two different concepts. Hazards should be thought of causal factors whereas risk means … whatever someone says it means (despite many published definitions). In this book I use the definition in ISO31000 – the “effect of uncertainty on objectives” (ICMM, 2016).

11.2.1 Hazard

Hazard is not the same as risk and perhaps should be thought of as a causal factor that might combine with other causal factors to result in an event. The Health and Safety at Work Act 2015, section 16 defines hazard to include:

… a person’s behaviour where that behaviour has the potential to cause death, injury or illness to a person (whether or not that behaviour results from physical or mental fatigue, drugs, alcohol, traumatic shock, or another temporary condition that affects a person’s behaviour).

Although this appears to be focused on behavioural or human factors, note that it is an inclusive definition and other factors could also cause death, injury, or illness to a person.

ISO45001 (2018) defines hazard as “source with a potential to cause injury and ill health” and notes “hazards can include sources with the potential to cause harm or hazardous situations, or circumstances with the potential for exposure leading to injury and ill health”.

A hazard is something with “the potential to cause adverse effects” (Benke & Cross, 2019, p. 35). A hazardous substance can be harmful if it is toxic, and a worker is exposed to the right concentration that can be absorbed. Some hazardous substances are not hazardous to health in one state but become hazardous if that state changes. For example, metalworking fluid as a liquid is not usually hazardous, but if cleared from a surface using a compressed airgun (eg, in a in machining workshop) forms a mist that can be inhaled (Bailey et al., 2022).

We can manage human factors – performance-shaping factors – that lead to errors; we all make mistakes, forget to do things, get tired (before, during and because of work), do things in the wrong sequences, break rules – or in some other way create a performance error.

11.2.2 Risk: in search of a perfect definition

Any assessment of risk in an organisational setting (and thus understanding of the effectiveness of risk assessments in informing decision makers) requires understanding what risk is. Ideally, a definition of risk would be broadly acceptable to lay people, decision makers, practitioners, and academics. However, definitions of risk always seem to result in controversy and debate – even in the same edition of a journal (Leitch, 2010; Purdy, 2010). Is it possible to arrive at a “Goldilocks definition” of risk – one that is “just right”?

Definitions of risk from academic literature

While many people have attempted to define risk, there is no commonly agreed definition of risk within, let alone between, academic disciplines (Aven & Renn, 2009). Different people, disciplines, groups, and cultures perceive and define risk differently – a problem that has been discussed by many authors – and this may contribute to frequent mismatches between the findings of risk assessors and the needs of decision makers and other stakeholders. An extensive review of the definitions of risk (Boholm et al., 2016) concluded that risk carries so many quantitative and qualitative meanings that it is difficult to define the word in any single way that is acceptable to most, let alone all, users.

Some seemingly objective definitions of risk are based on how risk is measured (eg, probability, size of loss, variance of the distribution of all possible consequences), but remain estimates of uncertainty (Alcock et al., 2011; Walker, P. L. et al., 2003; Warner, 1983). Other definitions consider subjective or objective perceptions of risk, showing the distinct differences between “social scientists” and “engineers” (Douglas & Wildavsky, 1982; Warner, 1992, p. 2; Wynne, 1992). Some definitions of risk are a way of measuring risk (eg, risk = likelihood x consequences) or are a conceptual formula (Risk is proportional to Hazard x Exposure or R ∝ H x E) (Benke & Cross, 2019, p. 35) but neither explains what risk is.

For some authors the social and subjective dimensions of risk are more important than considerations of the technical content (Zinn & Taylor-Gooby, 2006), although a few have pragmatically attempted to deconstruct the notion that the subjective and objective are independent and antithetical concepts (Bourdieu, 1977).

March & Shapira (2011) reviewed managerial perspectives on risk as a factor in decision making. They noted that classical decision theory saw risk as variations in possible outcomes, their likelihoods, and their subjective values: a risky outcome being one where negative variance is large or uncertain. Their review of empirical studies showed managers pay less attention to uncertainty about positive outcomes and that decision makers may define risk differently from academic writers. Similarly, Sitkin & Pablo (1992, p. 10) defined risk in relation to decision making as:

…the extent to which there is uncertainty about whether potentially significant and/or disappointing outcomes of decisions will be realised.

Jüttner, Peck, & Christopher (2003, p. 200) defined supply chain-related risk as “the variation in the distribution of possible supply chain outcomes, their likelihood, and their subjective values”. Reference to “variation” and “subjective” suggest uncertainty.

For sociologists the “dominant discourse of risk” has been summarised as being a body of knowledge represented by a range of documents such as articles, textbooks and standards (including ISO31000, 2009, 2018) that bring “risk” as a subject into existence (Hardy & Maguire, 2016, p. 81). While this knowledge may be used by those such as risk assessors who determine and report on the nature and level of risk so that others can respond to their findings, are they using the same knowledge as the responders?

A review of the epistemology of risk covered definitions used in mathematics and logic, science and medicine, economics, sociology, the arts, philosophy and theology, and concluded (Althaus, 2005, p. 580):

If risk is defined as the application of some form of knowledge to the unknown in an attempt to confront uncertainty and make decisions, then each discipline can be said to apply its own forms of knowledge to uncertainty that uniquely “creates” varying types of risk.

Inclusion of “the application of some form of knowledge” in a risk definition was unusual in such a review but the reference to uncertainty confirmed the key role this plays in approaches to risk in many disciplines. While Althaus’ inclusion of sociology, the arts, philosophy, and theology acknowledged differences between subjective and objective risk it left unanswered how those differences might be reconciled. Hansson (2010, p. 236) succinctly summarised some of those differences suggesting:

… an accurate and reasonably complete characterisation of a risk must refer both to objective facts about the physical world and to (value) statements that do not refer to objective facts about the physical world.

This aligned with “the need for awareness of both the factual and the value dimensions of problems, and of the complexities in both” (Funtowicz & Ravetz, 1992, p. 253), capturing the duality of subjective and objective risk, the need to take account of the tangible and intangible character of risk and of the articulated and unarticulated concerns of stakeholders.

Dunning-Kruger effect

A major problem in risk management is overconfidence and ignorance of a person of their own ignorance, the “inability of the incompetent to recognize their incompetence” (Pennycook et al., 2017), their unknown unknowns. This is often referred to as the Dunning-Kruger effect in which (Dunning, 2011):

… poor performers in many social and intellectual domains seem largely unaware of just how deficient their expertise is. Their deficits leave them with a double burden—not only does their incomplete and misguided knowledge lead them to make mistakes but those exact same deficits also prevent them from recognizing when they are making mistakes and other people choosing more wisely.

Uncertainty and risk

Knight (1921, pp. 19-20) attempted an early definition of risk, arguing it sometimes means “a quantity susceptible of measurement” (ie, objective) while at other times there was such uncertainty that risk was not measurable. This led Knight to see risk and uncertainty as two distinct concepts: “if you don’t know for sure what will happen, but you know the odds, that’s risk, and if you don’t know the odds, that’s uncertainty”, a view that has prevailed in some disciplines. However, uncertainty now forms part of many definitions of risk and may be ontological (incapable of reduction by further investigation) or epistemic (capable of reduction by collecting better data to enable better structural understanding). This might be done by establishing a common framework for discussion leading to different people gaining an appreciation of alternative points of view. However, although each may have access to the same data, they may reach different conclusions.

Uncertain means “the conscious awareness of ignorance” (Spiegelhalter, 2024, p. 19) or “not known, reliable, or definite” while certain means “able to be firmly relied on to happen or be the case” (Concise Oxford Dictionary, 2011).

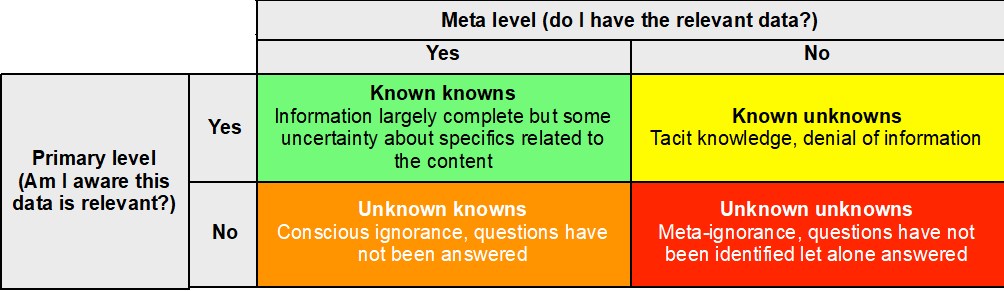

Bammer et al. (2008) summarised uncertainty about knowledge, arguing there are three types of unknowns, while Evans (2012) suggested a fourth combination of knowns and unknowns as summarised in Figure 33.

Uncertainty has been researched by many academics, including Ale (2002) (who argued that only some uncertainties can be assessed using structured techniques and that uncertainty pervades all stages in risk assessments) and Aven (2011) (who, discussing uncertainty in the application of the precautionary principle, showed why uncertainty may not be fully understood by some risk practitioners or decision makers).

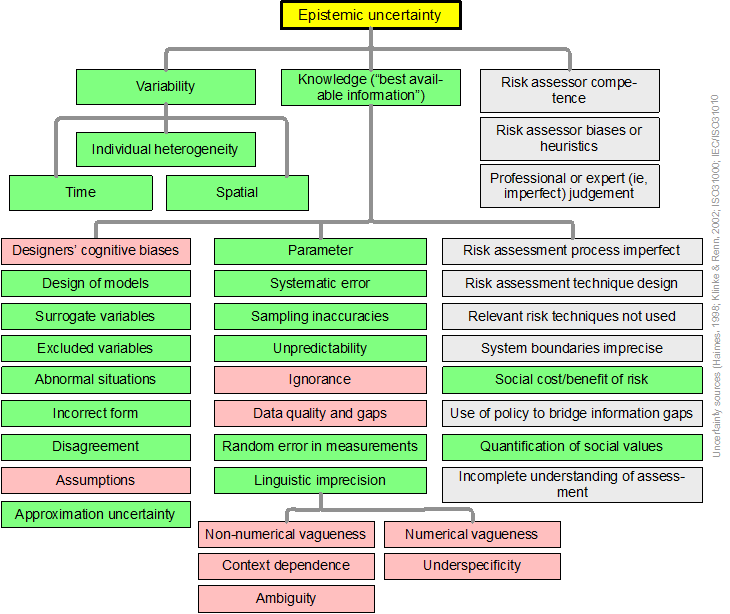

Haimes (1998, pp. 238-252) summarised some of the many sources of epistemic uncertainty shown in Figure 34 (expanded to include the work of other authors), leading to the conclusion that uncertainty is part of risk and so should form part of all risk assessments. In Haimes’ basic taxonomy (green in Figure 34), there may be variability across time, geography and the individuals who are the subject of a risk assessment. The knowledge used to inform a risk assessment may be selected inappropriately due to, for example, the biases of assessors or model designers and gaps in data. Poor design of a risk assessment or failure to train assessors in relevant risk techniques may also result in uncertainty. The US National Research Council (2009) report also suggested areas of uncertainty (pink in Figure 34) as did other authors (not colour coded).

Sources: Adapted by author from Haimes (1998), Kasperson (2008), Morrison & Morgan (1999), National Research Council (2009) and Regan, Colyvan & Burgman (2002)

As Figure 34 shows, there are so many variables that no risk assessment can claim to respond to them all accurately and even an “expert judgement” based on the best available information may be inaccurate (Fischhoff et al., 1980). Thus, results of expert or professional judgement should be expressed in confidence ranges (Burgman, 2016). At its simplest, a manager can be asked how sure they are that an objective will be achieved. Perhaps: “send me an email with your certainty estimate in it – how probable is it that this will be achieved?”.

Finally, definitions of risk might matter little provided they are clearly stated in any risk assessment or risk management activity (Aven, 2013). This enables some rational discussion about risk but may not respond to the concern that control of the definition of risk “is an exercise in power”, capable of swaying the results of a risk assessment (Slovic, 1999, p. 699).

In summary, in the objectivist academic literature, risk is often defined as either:

- the effect of uncertainty on something of human value (eg, personal or organisational objectives), or

- the combination of probability of a consequence or, sometimes, the probability of an event (a way of measuring risk, not defining it).

Subjectivists see risk more as the intangible concerns of stakeholders. Thus, inclusion of uncertainty (and its effects on something of value) and subjective elements are important components of the definition of risk.

Definitions of risk from legislation, standards, and guidance documents

When the NZ Parliamentary Transport and Industrial Relations Committee (2015, p. 5) reported the Health and Safety Reform Bill (2014) back to the New Zealand House of Representatives it said: “We prefer the common meanings of ‘risk’ and ‘hazard’, to encourage people to consider what risk means to them, in their particular circumstances”. Given the nature of the duties of care set out for different PCBUs under the Health and Safety at Work Act (2015) this was an unfortunate decision because each duty-holder in a workplace might define risk differently, with potentially conflicting results of assessments.

Standards, codes, and guidance on risk management appear to be dominated by:

- ISO31000 (2018) Risk management – guidelines

- Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO, 2004, 2016) Enterprise Risk Management

- Project Management Institute’s Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBoK) (PMI, 2013)

- Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organization Procedural Manual (FAO/WHO, 2013)

- World Organization for Animal Health Terrestrial Animal Health Code (WOAH, 2014)

- Secretariat of the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC, 2004) Pest risk analysis for quarantine pests including analysis of environmental risks and living modified organisms.

These definitions are analysed in Table 10. Note that ISO45001 gives two different definitions of risk.

ISO31000, COSO and PMBoK are commonly used standards in the corporate sector. The FAO/WHO, WOAH and IPPC documents are widely used in relation to trade, food safety and animal health, and the Society for Risk Analysis glossary (SRA, 2015, not summarised above) provides several qualitative and quantitative definitions of risk, emphasising variations in how practitioners might use the word. Other standards give different definitions of risk (eg, the “combination of the probability of occurrence of harm and the severity of that harm” (Safety of Machinery ISO12100, 2010)).

During the development of ISO31000 difficulties in defining “risk” were experienced by the multinational team of 40 experts, one of whom reported (Purdy, 2019): “When we decided on the ‘effect of uncertainty on objectives’ at the ISO RM WG in Vienna, we were clear that the ‘objectives’ were the highest level rationale for the organisation to exist. This succinct definition was unclear to some people and had to be elaborated on by five notes (reduced to three in the 2018 edition)”.

ISO45001 (2018, p. 5) OHS management systems contains two definitions of risk:

occupational health and safety risk: combination of the likelihood of occurrence of a work-related hazardous event or exposure(s) and the severity of injury and/or ill health that can be caused by the event or exposure(s)

risk: effect of uncertainty

The first defines risk in terms of how it is measured, not what it is, and implies the probability and severity of harm are certain (they rarely are). It is not consistent with the second definition (taken from ISO/IEC Annex SL (2020)) that is close to the ISO31000 definition but does not include objectives.

Table 10. Summary of definitions of risk from standards, codes, and guidance

| ISO31000 (2018) | ISO45001 (2018) | COSO ERM (2004, 2016) | PMBoK (PMI, 2013) |

FAO/WHO (2013) WOAH (2014) |

|

| Risk is … | effect of uncertainty on objectives | effect of uncertainty

OR OHS risk is combination of the likelihood of occurrence of a work-related hazardous event(s) or exposure(s) and the severity of injury and ill health that can be caused by the event(s) or exposure(s) [Similar to note 4 to the ISO31000 definition] |

… the possibility that events will occur and affect the achievement of strategy and business objectives | … an uncertain event or condition that, if it occurs, has a positive or negative effect on one or more project objectives such as scope, schedule, cost, and quality | … a function of the probability of an adverse health effect and the severity of that effect, consequential to a hazard(s) in food |

| An effect | Explicitly included | Explicitly included in the plain definition but not in the second definition | Explicitly included | Explicitly included | Explicitly included |

| Objectives | Explicitly included and examples given | Not included | Explicitly included and examples given | Explicitly included and examples given | Not explicit but other documents refer to the objective of human health |

| Positive or negative | Both included | Negative only in the second definition | Negative only | Both included | Negative only |

| Multiple potential causes | Multiple causes are included via the definition of “event” | Multiple causes are included | Not mentioned | Multiple causes included | Not mentioned |

| Potential events | Explicitly included in note 3 | Not mentioned | Explicitly included | Explicitly included | Not mentioned |

| Multiple potential consequences | Consequences as plural included in note 3 | Human health only | Not mentioned | Multiple consequences explicitly included via use of the word “impacts” | Implies single effects |

| Combination of consequences and their likelihood (as distinct from likelihood of an event) | Included in note 4 | Uses likelihood of an event | Not specifically stated | Not specifically stated | Uses the probability of an adverse consequence |

| Uncertainty | Explicitly discussed in note 5 and applicable to context, causes, events, or consequences | Not discussed but the second definition uses the uncertain word “likelihood” | Implied by use of the word “possibility” | Explicitly included | Implied by use of the word “probability” |

Definitions used in guidance documents have increasingly referred to uncertainty as part of risk (Aven, 2023). In the definitions of risk this is either plainly stated or implied. Thus, any risk assessment is an uncertain estimate of future outcomes and how they will affect objectives, the accountabilities of managers (Birkinshaw & Jenkins, 2010), or some human values. This is especially clear in ISO31000 (which sees uncertainty existing in relation to objectives) and PMBoK, and least clear in the WHO/FAO guidance.

In this book the ISO31000 definition is used unless otherwise stated.

A model of risk

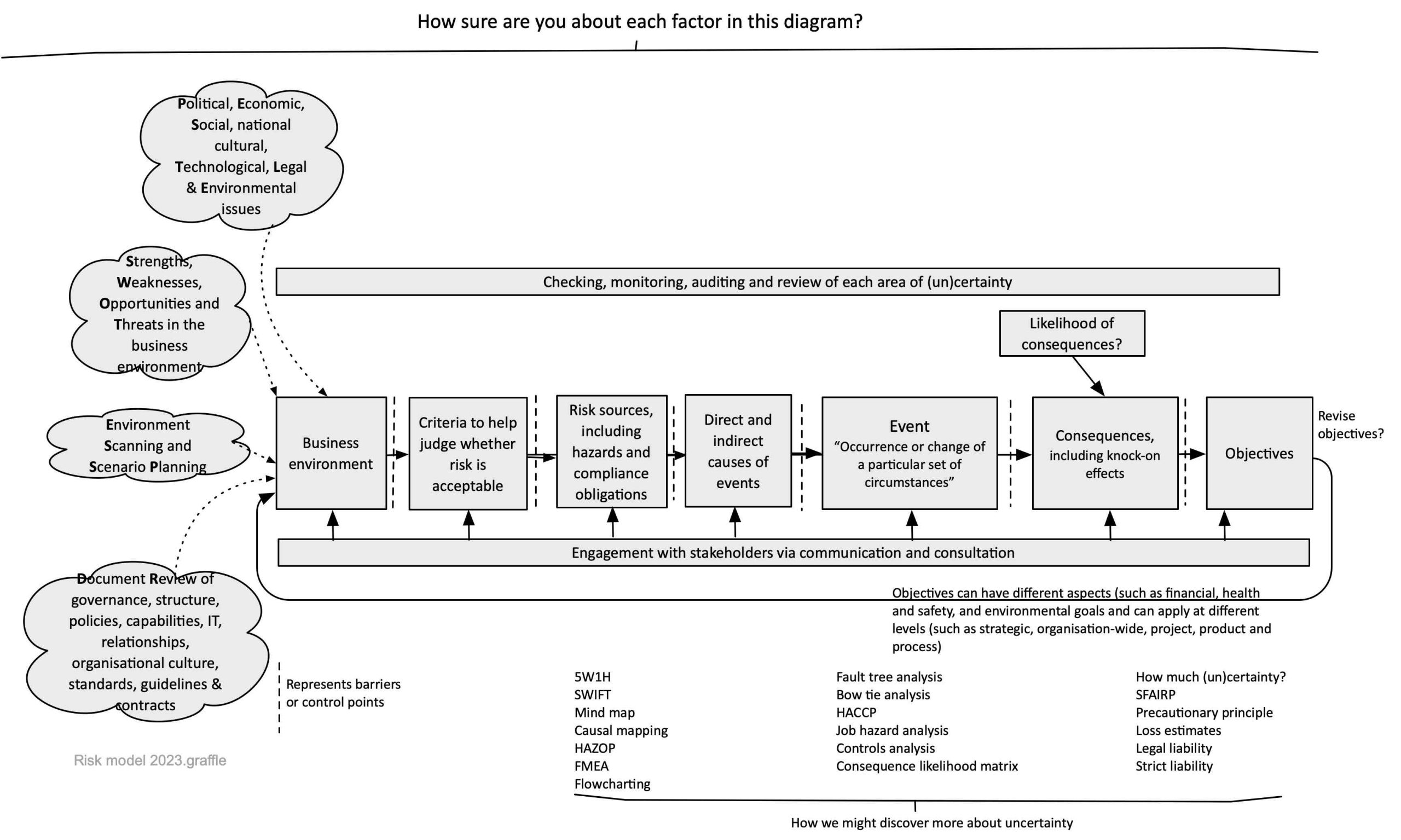

Figure 35 illustrates how risk may arise due to factors in the external or internal context, or both. As the causal factors flow from left to right in the diagram, they become events that give rise to consequences. These in turn impact on objectives.

At the risk analysis stage, risk factors such as the probability or likelihood of the consequences, the velocity, or speed from initiation to effect on objectives, the effectiveness of controls, and the uncertainty of each factor are considered. Risk may be described as “inherent” (no controls in place or considered), “residual” (taking account of current controls), or after treatment (if planned treatments are implemented as intended).

If a risk is evaluated as unacceptable “as is” (whether the consequences are positive or negative), it must be treated. The selected treatments may be designed to modify the context, sources of risk, initiating events, events, consequences, or their impacts on objectives.

However, uncertainty remains about each factor unless and until a risk has eventuated and is no longer uncertain. At that point in time, the risk has become an issue requiring some management attention. Each issue arising from a risk that has eventuated may, in turn, become a risk with or without knock-on effects.

This approach to risk suggests how people in governance and management can think about risk and its management. It also links with a variety of risk techniques that help us assess risks, also as suggested in Figure 35.

This risk model helps us think about how risks come to exist and change over time. For example:

- When a change in the external context occurs and gives rise to uncertainty (risk), how does your organisation respond? Is there a coordinated response?

- When a change in the internal context is planned, is there a coordinated approach to reduce uncertainty?

11.3 Risk management – managing uncertainty

What is risk management?

Risk management is the “coordinated activities to direct and control an organisation with regard to risk” (ISO31000, 2018). We can substitute the definition of risk into this definition to give:

“Coordinated activities to direct and control an organisation with regard to effect of uncertainty on objectives”.

When interpreted like this it becomes clearer that most people and organisations do manage uncertainty to some extent, but some do so better than others.

If risk management is to be effective, it must be:

- directed from the governance level (the “tone from the top”)

- coordinated by executive management

- consistently implemented by management at all levels.

This approach to risk management is based on ISO Annex SL (ISO/IEC Annex SL, 2020) – section 2.2.1 of this book. It is aligned with quality, environmental and other areas of management covered by management system standards (eg, AS/NZS ISO 14001, 2016; ISO9001, 2015) and the COSO (2017) and Project Management Institute PMBoK (PMI, 2013) models.

Risk management is about managing uncertain causes, events, consequences, and the likelihood of those consequences. While you will need to find out what your stakeholders understand by “risk” and “risk management” you should seek out those uncertainties and report on them and the uncertainties associated with your approach to “risk assessments” and the techniques you use.

Neil Crockford (first published in 1975, reprinted in 2005) argued that “risk management must become part of the function of all managers whatever their job title, and its techniques an expected management skill” and noted “the development of risk management is part of a more general development of managerial science”. Most tellingly, Crockford argued:

… all management is risk management. It should not be thought, because the ultimate responsibility for the management of serious risk will remain with the board, that risk management is a technique to be used by top management only, with the technical assistance of a corporate risk manager. Responsibility for risk management, if it is to be effective, must be among the responsibilities of line management.

11.3.1 The risk management process and risk assessments

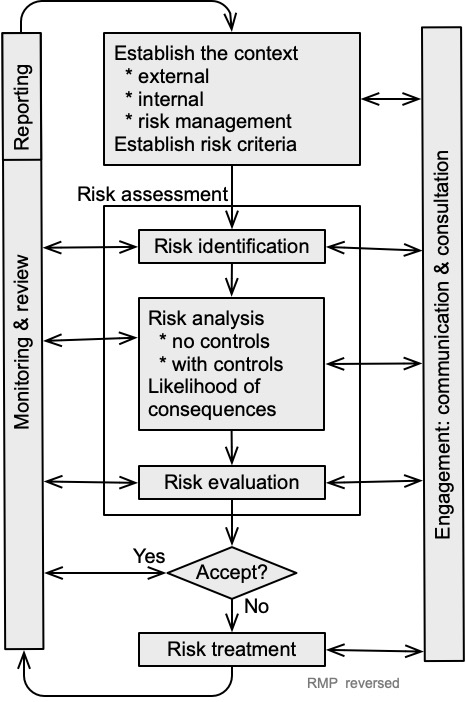

An amended version of the risk management process in ISO31000 (2018) is shown below.

Some key points

- Engagement (communication and consultation) should be part of each stage in the process.

- It is essential to understand the context – the business environment – in which a risk is assessed and managed.

- Monitoring and review should be part of each stage in the process.

- Criteria for risk evaluation are developed from factors in the context.

- Risk assessment includes three sub-stages:

- risk identification

- risk analysis

- risk evaluation.

- If a risk is not acceptable “as is” it must be treated.

- Risk analysis is part of risk assessment.

Decision makers can use the process to help check if risks are being assessed using a good process, including engagement (communication and consultation).

Hazard management doesn’t work as well as risk management

- Hazard, as defined, has no relationship with objectives and has purely negative consequences.

- A hazard might be called a “significant hazard” or a “major hazard”, but each requires assessment of the hazard and how it might affect people.

- There are too many hazards to manage them all but as soon as we start to rank them for attention, we are assessing risk, the effect of uncertainty on objectives.

- To manage risk we need to manage uncertainty and its effects on objectives.

These problems were among the reasons the Health and Safety in Employment Act 1992 resulted in pointless arguments about “hazard” and “significant hazard” management.

Often, management systems are a response to an unacceptable nature or level of uncertainty and its effect on objectives. For example:

- our workers and other stakeholders might find current occupational health and safety performance unacceptable: the management response is to revise or implement a safety management system

- our reputation will suffer, or the regulatory agencies will prosecute us if we cause pollution or damage the environment: the management response is to revise or implement an environmental management system

- our customers may not buy our product if the quality is variable, or it fails to work as intended: the management response is to revise or implement a quality management system.

However, there is good evidence that implementing such management systems may not work if they are adopted for the wrong reasons (eg, our competitors are doing it so it must be good; we will get insurance rebates if we implement a safety management system).

What are critical success factors for effective risk management?

Some critical success factors (CSF) and necessary conditions (NC) for effective management of uncertainty and its effect on objectives are summarised in the following table.

Table 11. Some critical success factors for effective management of uncertainty and its effect on objectives

|

CSF: Supportive organisation |

CSF: Competent people |

| Clear objectives form part of the governance structure

Continual communications about management of uncertainty and its effect on objectives performance The organisation places a real emphasis on continual improvement Availability of adequate resources Buy-in from all stakeholders A culture that recognises that uncertainty is inevitable Uncertainty is assessed and acted on whenever modification or changes are planned or occur to the organisation, people, processes, or plant Acceptance of the need to change in response to uncertainty and its effect on objectives Suitable contractual framework to support the process for management of uncertainty and its effect on objectives |

Designated individuals fully accept accountability for the management of uncertainty and its effect on their objectives

Shared understanding of the key concepts and principles of management of uncertainty and its effect on objectives A common language and agreement of key management terms Recognition of the need for continuous training of staff Competent staff (ie, relevant qualifications and experience) Combination of theoretical knowledge, behaviours, and attitudes |

|

CSF: Appropriate methods, tools, and techniques |

CSF: Simple, scalable process |

| Relevant level of infrastructure and software tools to support appropriate level of implementation

Training in the selected methods, tools, and techniques Integrated toolkit, both internally coherent and interfacing with other business tools and systems The organisation uses a consistent and structured approach to risk assessment |

Uncertainty and assumptions and their management are considered in all decision making

Recognition that “one size fits all” is the wrong approach The framework for management of uncertainty and assumptions are part of the overall business management framework A documented process for management of uncertainty and assumptions and their effect on objectives Clear instructions on “what to do” when uncertainty or the assumptions are too large |

11.3.2 Research: the benefits of effective management of uncertainty and assumptions

In the private sector, effective adherence to compliance obligations is increasingly seen by market analysts as evidence of effective management leading to greater stability in earnings. At the organisation level, effective risk management helps develop resilience in the face of risks with negative consequences while enabling taking opportunity from risks with positive consequences.

There is good experience and research evidence that effective risk management adds value to private sector organisation (eg, increased share price, profits, dividends) and public sector and not-for-profit organisation (eg, service delivery, dependability, service quality). A summary of some research on such benefits is in Table 12.

Effective management of uncertainty and its effect on objectives (“risk”) enables change and adaptation when technology, policies, markets, or expectations change, or when legislation imposes new or increased expectations. It also increases trust in governance of a PCBU.

Table 12. Evidence for the benefits of effective risk management

| Activity | Research findings |

| OHS in construction | In the UK the Construction (Design and Management) Regulations (CONDAM) were introduced to comply with a European Union Directive and to help reduce the rate of harm to workers. The Regulations seem to have driven professionalisation of some parts of the construction industry and led to designers becoming involved earlier in projects than was previously the case (Bennett, E. & Gilbertson, 2006) |

| OHS in construction | “Human characteristics like respect, trust, clarity, pre-emption, challenge, consistency, collaboration, motivation, empowerment, communication, openness, fairness and assurance” were key to the positive outcomes for the London Olympic Park. Many of the research findings offer benefits across a wide range of construction projects and for different companies in the construction supply chain (Bolt et al., 2012; Cheyne et al., 2012) |

| OHS in construction | Company profitability increases with a low number of accidents but reduces as the number of accidents increases (Estudillo et al., 2024; Forteza et al., 2017). |

| OHS & financial | Collective action in the process industry helps reduce the destruction of financial and non-financial value if a major event causes significant loss of life (Brown, G. D. et al., 2015) |

| OHS | Safety management has a positive influence on safety performance, competitiveness performance, and economic-financial performance and provides evidence of the compatibility between worker protection and corporate competitiveness (Fernández-Muñiz et al., 2009) |

| OHS | There is increasing evidence that a healthy and safe working environment can increase productivity and, in turn, business profits. Certain necessary ingredients are required, including effective engagement of employees by management (Finneran et al., 2012) |

| OHS | There is some evidence for a link between occupational health and safety, business performance and productivity in New Zealand but the data is skewed towards larger firms, often in the USA (Lamm et al., 2007) |

| OHS | A desktop audit of management of safety-related risks by the 150 largest companies listed on the ASX found a positive link between corporate safety management and share price (Larsson et al., 2007) |

| Corporate governance and share market performance | Australian research investigated companies that had adopted the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) Corporate Governance Council’s Principles of Good Corporate Governance and Best Practice Recommendations (ASX Corporate Governance Principles). The companies with greatest compliance with the Principles were found to outperform less compliant companies in shareholder performance, operating performance and one-year sales growth (Brown, R. & Gørgens, 2009) |

| Share price | A positive effect on share price was found in companies forming captive insurers (although other research has found no benefits or even dis-benefits) (Cross et al., 1986) |

| Supply chain disruption | On average, supply chain disruption led to a 10% reduction in share price. Later research found the reduction could be as high as 40%(Hendricks & Singhal, 2003, 2005a, 2005b). Firms with operational slack experienced less negative effect on their share price (Hendricks et al., 2009) |

| Share price | A reputation for social responsibility has been found to protect companies from a fall in share prices after a crisis(Knight, R., 2020). Sudden positive increases in share price due to unforeseen events can be maintained (while negative effects can be reduced) by competent and assertive responses from a company (Knight, R. & Pretty, 2003) |

| Trust in organisations | Trust is hard to create and maintain and easy to destroy. While trust is intangible its loss can lead to financial damage to the value of “goodwill” (Kramer, 1999; Schnietz & Epstein, 2005) |

| Environmental events | Environmental incidents have an effect on company value in Europe but less so in the USA, with European companies taking more voluntary action to avoid such events (Lundgren & Olsson, 2010) |

| Firm value | Using the recent Standard & Poors risk management rating, there was evidence of a positive relationship between increasing levels of risk management capability and company value (McShane et al., 2011) |

| Price/earnings ratio | Effective management of physical or insurable risks was found to reduce the frequency of losses and so improve the price/earnings ratio. The study found that companies with strong management of physical risks (caused by, for example, fire, flood, or earthquake) on average had earnings that fluctuated by 17.9% whereas companies with weak physical risk management practices, on average, had earnings that fluctuated by 31.4%. “The stronger the physical risk management practices, the lower the earnings volatility; the weaker the physical risk management practices, the higher the earnings volatility” (Pretty, 2011). See also (Knight, R., 2020) |

| Organisational health and safety | Management practices focusing on “hard” incentives, rewards, and consequences, as well as on employees’ mind-sets and values, make workplaces safer (Lim et al., 2018) |

| Economic performance of construction firms | Risk on site influences accident rates and these influence economic performance (Forteza et al., 2017). See also Lari (2024) |

11.3.3 Alternative approaches – dynamic risk management

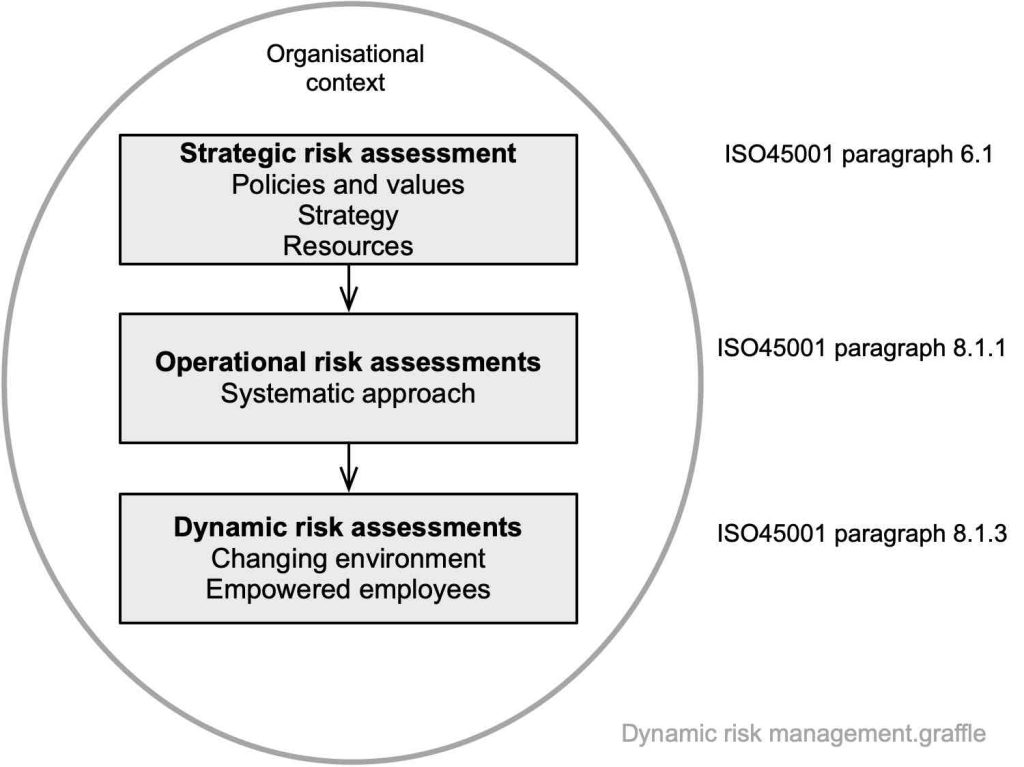

The concept of dynamic risk management has evolved since 1998 (Anon, 1998) when it was advocated for use in the UK fire services (Asbury, 2014). As summarised in Figure 36, this approach suggests establishing policies at a strategic level to give shape and direction for what an organisation exists to do. A systematic approach is developed at an operational level, while dynamic decisions are made at a local level in response to an environment that is volatile, uncertain, complex or ambiguous (“VUCA”) (Bennett, N. & Lemoine, 2014a, 2014b).

Reference to three key clauses in ISO45001 have been added to suggest how this model might be used in an occupational health and safety management system.

Finally, alternative views on risk and risk management are given in Rausand (2020) and Spencer & Jerman (2019, p. 42) who discuss the need for clarity and (within an organisation) a single meaning for the word risk.

11.3.4 Summary

This brief review shows there is no perfect definition of risk – one that is “just right”. The wide range of definitions of risk demonstrates as much about the origins and disciplines of authors as the definitional differences and, in some situations, this might require negotiation of an agreed definition. Failure to understand differences in definitions of risk may result in failure to communicate and consult effectively with stakeholders, including decision makers, each of whom may have different definitions and perceptions of risk.

While the above suggests a risk assessor should define risk in the context of their work and make clear to stakeholders how the word is being used, the analysis in Table 10 suggests ISO31000 provides an adequate definition of risk (“effect of uncertainty on objectives”) because it links objectives – what organisations exist to achieve – and uncertainty. This view is supported by the COSO and PMBoK definitions which also refer to objectives. Inclusion of uncertainty in the ISO31000 definition is important because there is never certainty about achievement of organisational objectives unless and until they have been achieved. Such causal uncertainties need to be identified as part of a risk assessment.

Rather than use a contentious word, risk, we should use something more readily understood – uncertainty. Perhaps Estall & Purdy (2020) are right when they argue we should confront uncertainty and the assumptions we make, rather than (as so many people do) worry about what we mean by risk. Estall & Purdy give well-developed arguments for their opinion, and you will find this book follows a similar journey but in different words using different techniques.

I will try to use “uncertainty” in preference to “risk” but sometimes must use “risk” to help explain a concept. Crucially, always state what you mean by risk when writing a report. A reader may disagree with you, but they at least know what you are writing about.

11.4 References used in this chapter

Alcock, R., MacGillivray, B., & Busby, J. (2011). Understanding the mismatch between the demands of risk assessment and practice of scientists — The case of Deca-BDE. Environment International, 37(1), 216-225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2010.06.002

Ale, B. (2002, 2002/02/01/). Risk assessment practices in The Netherlands. Safety Science, 40(1), 105-126. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-7535(01)00044-3

Althaus, C. (2005). A disciplinary perspective on the epistemological status of risk. Risk Analysis, 25(3), 567-588. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2005.00625.x

Anon. (1998). Dynamic management of risk at operational events [Guidance Note J55076]. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, Norwich. https://www.ukfrs.com/sites/default/files/2017-09/Dynamic%20Management%20of%20Risk%20at%20Operational%20Incidents.pdf

AS/NZS ISO 14001: 2016 Environmental management systems – Specification with guidance for use, Standards New Zealand, Wellington.

Asbury, S. (2014). Dynamic risk assessment: the practical guide to making risk-based decisions with the 3-level risk management model. Routledge. https://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9781315858722

Aven, T. (2011). On Different Types of Uncertainties in the Context of the Precautionary Principle. Risk Analysis, 31(10), 1515-1525. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01612.x

Aven, T. (2013). On the meaning of a black swan in a risk context. Safety Science, 57(0), 44-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2013.01.016

Aven, T. (2023). On the gap between theory and practice in defining and understanding risk. Safety Science, 168, 106325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2023.106325

Aven, T., & Renn, O. (2009). On risk defined as an event where the outcome is uncertain. Journal of Risk Research, 12(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669870802488883

Bailey, C., Brookes, J., & Evans, G. (2022). Metalworking fluid and use of compressed airguns in machining: expert workshop [Research Report RR1171]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Bammer, G., Smithson, M., & Goolabri Group. (2008). The nature of uncertainty. In G. Bammer & M. Smithson (Eds.), Uncertainty and Risk: Multidisciplinary Perspectives (pp. 289-304). Earthscan Publications Ltd.

Benke, G., & Cross, M. (2019). Occupational health, basic toxicology and epidemiology. In S. Reed, D. Pisaniello, & G. Benke (Eds.), Principles of occupational health & hygiene: an introduction (3rd ed., pp. 27-51). Allen & Unwin.

Bennett, E., & Gilbertson, A. (2006). The commercial case for applying CDM [Research Report RR0467]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Bennett, N., & Lemoine, G. J. (2014a, 2014/05/01/). What a difference a word makes: Understanding threats to performance in a VUCA world. Business Horizons, 57(3), 311-317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2014.01.001

Bennett, N., & Lemoine, G. J. (2014b). What VUCA Really Means for You. Harvard Business Review(January/February).

Birkinshaw, J., & Jenkins, H. U. W. (2010, Winter2010). Making better risk management decisions. Business Strategy Review, 21(4), 41-45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8616.2010.00704.x

Boholm, M., Möller, N., & Hansson, S. O. (2016). The Concepts of Risk, Safety, and Security: Applications in Everyday Language. Risk Analysis, 36(2), 320-338. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12464

Bolt, H., Haslam, R., Gibb, A., et al. (2012). Pre-conditioning for success: Characteristics and factors ensuring a safe build for the Olympic Park [Research Report RR0955]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge University Press.

Brown, G. D., Corbet, S., McMullan, C., et al. (2015, 12//). Do industrial incidents in the chemical sector create equity market contagion? Journal of Safety Research, 55, 115-119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2015.08.009

Brown, R., & Gørgens, T. (2009). Corporate governance and financial performance in an Australian context [Working Paper 2009 – 02]. The Treasury, Canberra. http://www.treasury.gov.au/documents/1495/PDF/TWP_2009-02.pdf

Burgman, M. (2016). Trusting Judgements: How to Get the Best out of Experts. Cambridge University Press.

Carson, P. A., & Snowden, D. (2011). Health, safety and environment metrics in loss prevention – part 2. Loss Prevention Bulletin(221), 12-17.

Cheyne, A., Hartley, R., Gibb, A., et al. (2012). Talk the talk – walk the walk: An evaluation of Olympic Park safety initiatives and communication [Research Report 12.1]. IOSH Publishing Ltd, Wigston. http://www.iosh.co.uk/olympicpark

Concise Oxford Dictionary. (2011). (12th ed.). Oxford University Press Ltd.

COSO. (2004). Enterprise Risk Management – Integrated Framework: Application techniques [Report]. Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission, Jersey City, NJ.

COSO. (2016). Enterprise Risk Management – Aligning Risk with Strategy and Performance [Report ]. Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission, Jersey City, NJ.

COSO. (2017). Enterprise Risk Management – Aligning Risk with Strategy and Performance [Executive Summary]. Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission, Jersey City, NJ. https://www.coso.org/Pages/erm.aspx

Crockford, G. N. (2005). The Changing Face of Risk Management (first published in 1976 in The Geneva Papers)*. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance Issues and Practice, 30(1), 5-10. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.gpp.2510019

Cross, M., Davidson, W., & Thornton, J. (1986). The Impact of Captive Insurer Formation on the Parent Firm’s Value. The Journal of Risk and Insurance, 53(3), 471-483.

Douglas, M., & Wildavsky, A. (1982). Risk and Culture. University of California, Berkeley.

Dunning, D. (2011). The Dunning–Kruger Effect: On Being Ignorant of One’s Own Ignorance. In J. M. Olson & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 44, pp. 247-296). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-385522-0.00005-6

Estall, R., & Purdy, G. (2020). Deciding: A guide to even better decision making [Book ISBN 9798632417471].

Estudillo, B., Carretero-Gómez, J. M., & Forteza, F. J. (2024). The impact of occupational accidents on economic Performance: Evidence from the construction. Safety Science, 177, 106571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2024.106571

Evans, D. (2012). Risk intelligence: how to live with uncertainty. Atlantic Books.

FAO/WHO. (2013). Procedural Manual. Food and Agriculture Organisation, Rome. https://www.lexology.com/

Fernández-Muñiz, B., Montes-Peón, J. M., & Vázquez-Ordás, C. J. (2009). Relation between occupational safety management and firm performance. Safety Science, 47(7), 980-991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2008.10.022

Finneran, A., Hartley, R., Gibb, A., et al. (2012). Learning to adapt health and safety initiatives from mega projects: an Olympic case study. Policy and Practice in Health and Safety, 10(2), 81-102.

Fischhoff, B., Lichtenstein, S., Slovic, P., et al. (1980). Approaches to Acceptable Risk: A Critical Guide [Research Report NUREG/CR-1614: ORNL/S~b-7656/]. Oak Ridge National Laboratory,

Forteza, F. J., Carretero-Gómez, J. M., & Sesé, A. (2017, 2017/04/01/). Occupational risks, accidents on sites and economic performance of construction firms. Safety Science, 94, 61-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2017.01.003

Funtowicz, S., & Ravetz, J. (1992). Three types of risk assessment and the emergence of post-normal science. In S. Krimsky & D. Golding (Eds.), Social theories of risk. Praeger.

Haimes, Y. (1998). Risk modelling, assessment and management. John Wiley & Sons.

Hansson, S. O. (2010). Risk: objective or subjective, facts or values. Journal of Risk Research, 13(2), 231-238. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669870903126226

Hardy, C., & Maguire, S. (2016, 01//). Organizing risk: discourse, power, and “riskification”. Academy of Management Review, 41(1), 80-108. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2013.0106

Health and Safety at Work Act (2015). New Zealand http://www.legislation.govt.nz/

Health and Safety Reform Bill (2014). New Zealand http://www.legislation.govt.nz/

Hendricks, K. B., & Singhal, V. R. (2003). The effect of supply chain glitches on shareholder wealth. Journal of Operations Management, 21(5), 501-522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2003.02.003

Hendricks, K. B., & Singhal, V. R. (2005a, May 1, 2005). Association Between Supply Chain Glitches and Operating Performance. Management Science, 51(5), 695-711. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1040.0353

Hendricks, K. B., & Singhal, V. R. (2005b). An Empirical Analysis of the Effect of Supply Chain Disruptions on Long-Run Stock Price Performance and Equity Risk of the Firm. Production and Operations Management, 14(1), 35-52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-5956.2005.tb00008.x

Hendricks, K. B., Singhal, V. R., & Zhang, R. (2009). The effect of operational slack, diversification, and vertical relatedness on the stock market reaction to supply chain disruptions. Journal of Operations Management, 27(3), 233-246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2008.09.001

Hillson, D., & Simon, P. (2007). Practical Project Risk Management: the ATOM methodology. Management Concepts.

ICMM. (2016). Good practice guidance on occupational health risk assessment [report 2nd edition]. International Council on Mining and Metals, www.icmm.com

IPPC. (2004). Pest risk analysis for quarantine pests including analysis of environmental risks and living modified organisms [Guidance Note ISPM11]. Secretariat of the International Plant Protection Convention, Geneva. https://www.ippc.int/file_uploaded/1146658377367_ISPM11.pdf

ISO9001: 2015 Quality management systems – Requirements, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

ISO12100: 2010 Safety of machinery — General principles for design — Risk assessment and risk reduction, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

ISO31000: 2009 Risk management – Principles and guidelines, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

ISO31000: 2018 Risk management – Guidelines, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

ISO45001: 2018 Occupational health and safety management systems: Requirements with guidance for use, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

ISO/IEC Annex SL. (2020). Proposals for management system standards. In Directives, Part 1: Consolidated ISO Supplement – Procedures specific to ISO (11th ed.). International Standards Organization. https://www.iso.org/directives-and-policies.html

Jüttner, U., Peck, H., & Christopher, M. (2003). Supply chain risk management: outlining an agenda for future research. International Journal of Logistics: Research & Applications, 6(4), 197-210.

Kasperson, R. (2008). Coping with deep uncertainty: challenges for environmental assessment and decision-making. In G. Bammer & M. Smithson (Eds.), Uncertainty and Risk: Multidisciplinary Perspectives (pp. 337-348). Earthscan Publications Ltd.

Knight, F. (1921). Risk, uncertainty and profit (1957 reprint ed.). Houghton Mifflin.

Knight, R. (2020). Corporate Reputation in Crisis: The Impact on Shareholder Value. Oxford Metrica, Oxford. https://www.oxfordmetrica.com/en/web/reputation-and-risk.aspx

Knight, R., & Pretty, D. (2003). Managing the risks behind sudden shifts in value. http://www.oxfordmetrica.com/public/CMS/Files/599/02RepComEY.pdf

Kramer, R. M. (1999). Trust and distrust in organizations: Emerging perspectives, enduring questions. Annual Review of Psychology, 50(1), 569.

Lamm, F., Massey, C., & Perry, M. (2007). Is there a link between Workplace Health and Safety and Firm Performance and Productivity? New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 32(1), 72-86.

Lari, M. (2024, 2024/02/01/). A longitudinal study on the impact of occupational health and safety practices on employee productivity. Safety Science, 170, 106374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2023.106374

Larsson, T., Mather, E., & Dell, D. (2007). To influence corporate OH&S performance through the financial market. International Journal of Risk Assessment and Management, 7(2), 263-271.

Leitch, M. (2010). ISO 31000:2009 – The New International Standard on Risk Management. Risk Analysis, 30(6), 887-892.

Lim, R., Rousseau, J.-B., & Weddie, B. (2018). The symbiotic relationship between organizational health and safety. McKinsey Quarterly. www.mckinsey.com

Lundgren, T., & Olsson, R. (2010). Environmental incidents and firm value-international evidence using a multi-factor event study framework. Applied Financial Economics, 20(16), 1293-1307. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603107.2010.482516

McShane, M. K., Nair, A., & Rustambekov, E. (2011). Does Enterprise Risk Management Increase Firm Value? Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 26(4), 641-658. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148558×11409160

Morrison, M., & Morgan, M. (1999). Models as mediating instruments. In M. Morgan & M. Morrison (Eds.), Models as mediators: perspectives on natural and social science (pp. 10-37). Cambridge University Press.

Mullen, P. (2007). How management behaviours associated with successful health and safety performance relate to those associated with success in other domains [Research Report RR0744]. Health and Safety Executive, Buxton. https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/publish.htm

National Research Council. (2009). Science and decisions: advancing risk assessment. National Academies Press.

Peace, C. (2019). The effectiveness of risk assessments in informing decision makers [PhD thesis, Victoria University of Wellington]. New Zealand. https://www.wgtn.ac.nz/library

Pennycook, G., Ross, R. M., Koehler, D. J., et al. (2017). Dunning–Kruger effects in reasoning: Theoretical implications of the failure to recognize incompetence. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 24(6), 1774-1784. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-017-1242-7

PMI. (2013). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (5th ed.). Project Management Institute,. www.pmi.org

Pretty, D. (2011). The Price/Earnings Ratio: new perspectives for achieving bottom-line stability [White Paper P09232]. FM Global, Johnston, RI. www.fmglobal.com

Purdy, G. (2010). ISO 31000:2009—Setting a New Standard for Risk Management. Risk Analysis, 30(6), 881-886.

Purdy, G. email to C. Peace, 5 May 2019,

Rausand, M. (2020). Risk assessment: theory, methods, and applications (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Regan, H. M., Colyvan, M., & Burgman, M. A. (2002). A taxonomy and treatment of uncertainty for ecology and conservation biology. Ecological Applications, 12(2), 618-628. https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2002)012[0618:ATATOU]2.0.CO;2

Schnietz, K. E., & Epstein, M. J. (2005). Exploring the Financial Value of a Reputation for Corporate Social Responsibility During a Crisis. Corporate Reputation Review, 7(4), 327-345. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1540230

Sitkin, S. B., & Pablo, A. L. (1992). Reconceptualizing the Determinants of Risk Behavior. Academy of Management Review, 17(1), 9-38.

Slovic, P. (1999). Trust, Emotion, Sex, Politics, and Science: Surveying the Risk-Assessment Battlefield. Risk Analysis, 19(4), 689-701. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1007041821623

Spencer, D., & Jerman, C. (2019). Risk-Led Safety: Evidence-Driven Management (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis Ltd.

Spiegelhalter, D. (2024). The art of uncertainty. Penguin Random House.

SRA. (2015). Glossary [Report]. Retrieved 15 June 2017, from https://www.lexology.com/

Transport and Industrial Relations Committee. (2015). Health and Safety Reform Bill. NZ House of Representatives, Wellington. http://www.parliament.nz/

Walker, P. L., Shenkir, W. G., & Barton, T. L. (2003). ERM in practice. Internal Auditor, 60(4), 51.

Warner, F. (Ed.). (1983). Risk Assessment: A Study Group Report. The Royal Society.

Warner, F. (Ed.). (1992). Risk: analysis, perception and management. The Royal Society.

WOAH. (2014). Terrestrial Animal Health Code [International agreement]. World Organisation for Animal Health, Paris.

Wynne, B. (1992). Risk and social learning: reification to engagement. In S. Krimsky & D. Golding (Eds.), Social theories of risk. Praeger.

Zinn, J., & Taylor-Gooby, P. (2006). Risk as an interdisciplinary research area. In P. Taylor-Gooby & J. Zinn (Eds.), Risk in Social Science. Oxford University Press.