10 Internal audit

10.1 Chapter overview

This chapter provides a brief overview of: the origins of internal audits; why they are needed, sometimes required; how an audit programme can be developed and individual audits carried out; a possible structure of audit reports.

Cross-reference to ISO31000; Annex SL clause 9; clause 9 in management system standards; and SafePlus requirements (section 2.2.5).

Definitions of italicised terms are in the Glossary.

Check for key readings, webinars, interviews, and videos for other resources. See especially Hutchinson et al. (2024).

Useful resources are Dyjack et al. (2003), Leung et al. (2015) and Moroney (2022). See also three Safe Work Australia research reports (Martinov-Bennie et al., 2014; O’Neill et al., 2013; O’Neill et al., 2015), and Wassenar (2024).

Relevant law

- Health and Safety at Work Act 2015

- Health and Safety at Work (Worker Engagement, Participation, and Representation) Regulations 2016

- Health and Safety at Work (General Risk and Workplace Management) Regulations 2016

- Health and Safety at Work (Major Hazard Facilities) Regulations 2016

Key questions

What is or will be the impact of artificial intelligence on the business?

If risk is the “effect of uncertainty on objectives“:

- what are the high-level and operational objectives of the organisation, activity, system, or item?

- what are the uncertainties about achieving the objectives?

- how do or will those uncertainties affect achievement of the operational objectives?

- to what extent can internal audits confirm that the management system controls those uncertainties to an acceptable level?

- to what extent are audits reliable?

10.1.1 Useful audit techniques

The following techniques may help when auditing the effectiveness of OHS management and controls.

- Assurance mapping (see section 21.3.2)

- Controls effectiveness rating (see section 21.3.6)

- Fishbone or Ishikawa analysis (section 21.3.12)

- Flowcharting or process mapping (see section 21.3.13)

- Inspections, physical surveys, and observations (see section 21.3.18)

- Interviews (see section 21.3.19)

- Literature or document review (see section 21.3.22)

- Management oversight and risk tree (MORT, see section 21.3.24)

- Organisation charts (see section 21.3.25)

10.2 Introduction

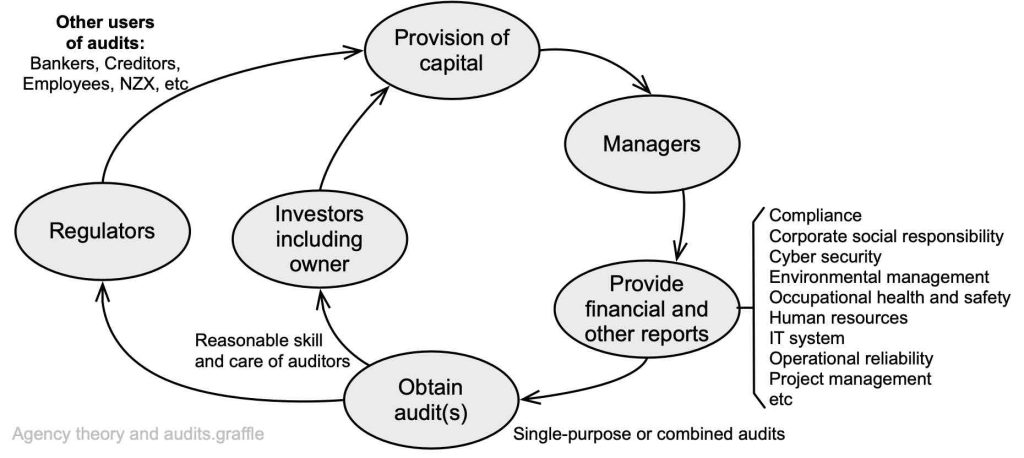

As a business grows it becomes increasingly difficult for the owner to maintain control and knowledge of all aspects of the undertaking and it becomes necessary to employ managers. However, managers may not have the same incentives or objectives as the owner and may seek to run the business for their own benefit (referred to as agency theory). The owner may then employ auditors to check the managers are carrying out their agree tasks. Audits of some form have been carried out for more than 1000 years (Leung et al., 2015, pp. 8-13) and their development and uses can be visualised as shown in Figure 31.

The information hypothesis is an alternative theory that claims audits improve the quality of information, enabling better decisions about investment in the business. Better information also helps monitor an agent’s performance.

The insurance hypothesis claims that auditors can be blamed if something goes wrong that results in major loss.

Finally, there may be legal requirements for audits, perhaps intended to protect investors who might be unable to check on the prudent management of a business.

Internal audits should be carried out at regular, planned intervals to give assurance that a management system is contributing to achievement of organisational objectives. An audit should examine whether the management system, including standard operating procedures and safe systems of work, fulfils organisational and stakeholder requirements, meets the requirements of one or more specific management system standards, and is being effectively implemented and maintained.

How ISO45001 can be used

Clause 0.5 (page viii of the standard) allows that “an organisation that wishes to demonstrate conformity … can do so by:

- making a self-determination and self-declaration, or

- seeking confirmation of its conformity by parties having an interest in the organization, such as customers, or

- seeking confirmation of its self-declaration by a party external to the organization, or

- seeking certification/registration of its OH&S management system by an external organization”.

Thus, a PCBU could use ISO45001 to progressively develop an OHSMS, making a self-determination as each part of the system is completed, and making a self-declaration to the board on conformance with that part – see section 44(4)(f) HSWA. The PCBU could also ask stakeholders to confirm conformity with requirements of mutual interest – see section 34 HSWA (“consult, co-operate with and co-ordinate activities”). When the OHSMS is believed to be complete the PCBU could then seek confirmation, certification, or registration from an external organisation.

Such a self-declaration could enable and form part of routine monitoring and review activities (0) that enable a PCBU to provide reasonable assurance of compliance with Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 sections 34-43.

SafePlus

SafePlus makes three requirements broadly related to audit and improvement.

- “3.3 The business monitors and evaluates progress against its health goals and safety goals

- 3.4 The business, with workers or their representatives, reviews and evaluates its effectiveness in risk management and broader health and safety management

- 3.5 The business uses ongoing monitoring, review, and evaluation activity to inform business decisions and change”.

These requirements could be applied in the same way as suggested above for ISO45001.

Major hazard facilities

Regulation 35 of the Health and Safety at Work (Major Hazard Facilities) requires the operator of a major hazard facility to review and revise the safety management system as necessary.

10.3 The audit programme and individual audits

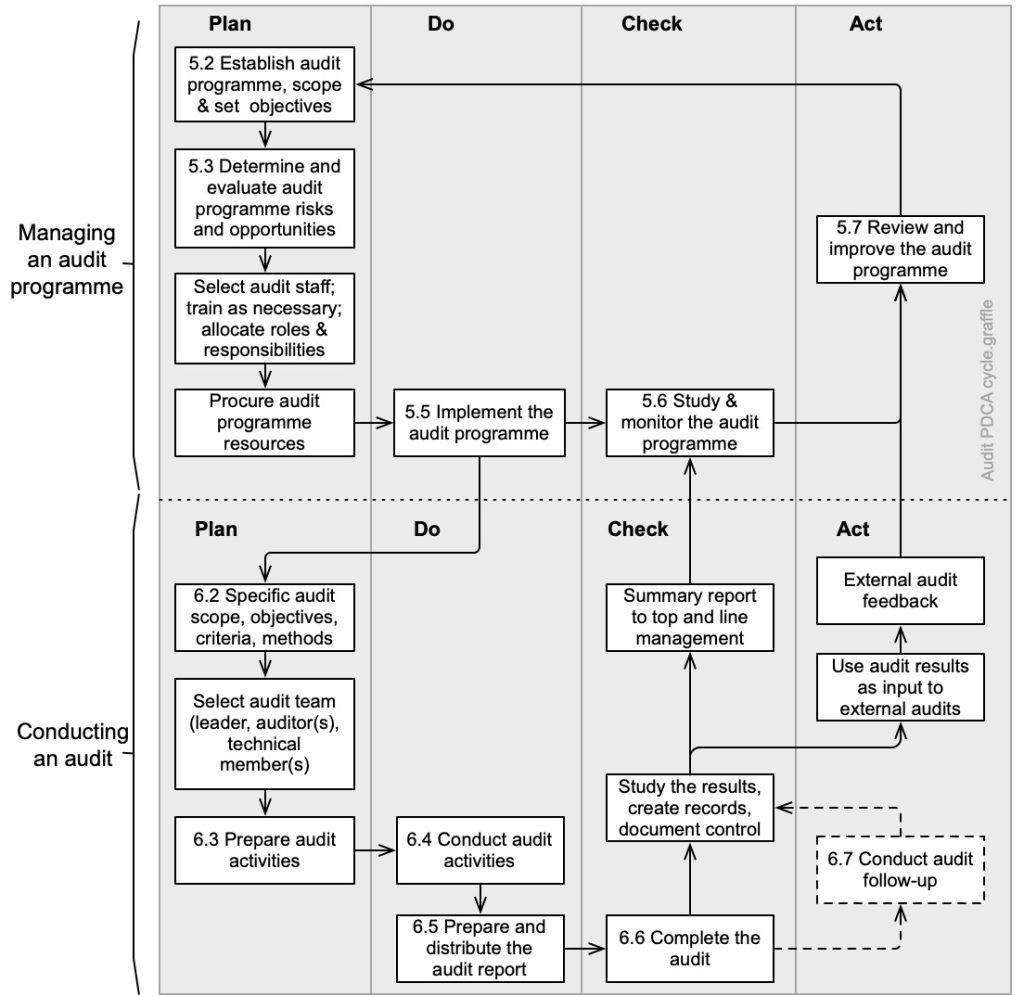

The high-level Plan Do Check Act (PDCA) process for developing an audit programme and conducting individual audits is summarised in Figure 32. See also section 2.2.1 of this book.

Source: Reproduced from AS/NZSISO19011: 2019

Figure 32 is adapted from figure 1, page 8, AS/NZS ISO19011. Numbers in each box are clause numbers in the standard. Some additional stages have been added to provide more detail, including using outputs from internal audits as inputs to external audits. For example, the internal audit programme might be agreed with the external auditor and a series of audits scheduled covering components of the OHSMS. If conducted to a standard set by the external auditor, these might be relied on as evidence. Such a standard would require sufficient independence of the internal auditor or team.

10.4 Initiating an audit

The following is a common pattern for initiating an individual audit but should be adapted to meet specific needs.

Audit scope

The audit scope is part of the audit programme.

Audit team leader

An audit team leader is appointed and reviews the audit scope. The team leader then contacts the auditee to confirm:

- audit scope

- audit dates and locations

- specific needs of the auditee, including site access and permissions

- relevant information and documents needed for the audit

- accommodation for the audit team

- specific issues about confidential or sensitive information

- acceptability of the proposed audit team members.

This discussion should help show if it will be possible to complete the audit to the required standard and within the proposed timetable and budget.

Critical, major, or key risks

Critical, major or key risks within the PCBU, activity or process to be audited should be understood by reading reports on monitoring activities (section 9.1), reviews, risk assessments and related documents. It then becomes possible to review the audit objectives in relation to the organisational objectives, document the context of the organisation and the activity or process.

Preparation of audit activities

In large audit projects it is generally necessary to arrange a regular meeting of team members who can summarise their findings so far and outline any difficulties encountered.

Kick off meeting and site tour

The first meeting is very important for setting out the audit scope – the terms of reference for the audit. This is when access to people is confirmed, and their contact details provided.

The audit team should seek a familiarisation tour of the facilities (see section 21.3.18) and the activity or process to be audited.

Specific audit activities are assigned to team members, together with relevant documents and contact details of people who are to be met or interviewed.

An important first step is to gain access to and understand the scope and scale of the documented information to be used in the audit. Documented information for the audit may include:

- manuals

- safe systems of work and standard operating procedures

- checklists.

Audit follow-up activities

Sometimes, an auditor may be asked to follow up on audit findings or suggest how non-conformances might be remedied to aid organisation improvement.

10.5 Outline of a risk-based audit report

Risk-based thinking

The term “risk-based thinking” may first have appeared in clause A.4 of ISO9001 (2015) Quality management systems which stated:

0.3.3 Risk-based thinking

Risk-based thinking … is essential for achieving an effective quality management system. The concept of risk-based thinking has been implicit in previous editions of this International Standard including, for example, carrying out preventive action to eliminate potential nonconformities, analysing any nonconformities that do occur, and taking action to prevent recurrence that is appropriate for the effects of the nonconformity.

ISO 9001:2015(E)

To conform to the requirements of this International Standard, an organization needs to plan and implement actions to address risks and opportunities. Addressing both risks and opportunities establishes a basis for increasing the effectiveness of the quality management system, achieving improved results and preventing negative effects.

Opportunities can arise as a result of a situation favourable to achieving an intended result, for example, a set of circumstances that allow the organization to attract customers, develop new products and services, reduce waste or improve productivity. Actions to address opportunities can also include consideration of associated risks. Risk is the effect of uncertainty and any such uncertainty can have positive or negative effects. A positive deviation arising from a risk can provide an opportunity, but not all positive effects of risk result in opportunities.

This International Standard applies the framework developed by ISO to improve alignment among its International Standards for management systems … (ie, Annex SL).

The definition of risk in ISO31000 is the “effect of uncertainty on objectives”. Its inclusion in “risk-based thinking” suggests auditors should be thinking about uncertainty and its effects on objectives.

Suggested headings for an audit report

The following are suggested headings for an audit report. The headings can be varied to suit the needs of the board, management, and other interested parties.

Overview

Whether the audit was a first-, second-, or third-party audit

Fit with the audit programme

The lead auditor and their competencies

The members of the audit team and their competencies

Any technical experts included in the audit team and their competencies

Audit criteria used:

-

- compliance obligations and other criteria

Audit scope and plan

Sources of audit evidence

-

- any control self-assessment by the auditee (21.3.7)

- document inspection (21.3.22)

- documented information (eg, standard operating procedures and safe systems of work)

- interviews or enquiring (21.3.19)

- observations (21.3.18)

- risk assessment by the auditor

- risk assessments by the auditee (the subject of paper HLWB509)

- site inspections (21.3.18)

- workshops (21.3.40)

Audit findings related to the objectives of the organisation

-

- causal factors or hazards

- control assurance maps

- controls currently in place, their effectiveness and any gaps

- credible consequences of events

- human factors and performance shaping factors

- legal requirements (eg, statutes, regulations, consents, contracts, legal liabilities)

- nature of current risk (ie, with controls already in place)

- level of current risk

- nature of risk if treatments are implemented

- level of risk if treatments are implemented

- other issues, including design and use of other parts of the system

- possible events

- treatment options and cost-benefit analysis

- treatment options effectiveness

Audit conclusions and recommendations

10.6 Chapter summary

This chapter has only briefly covered what internal audits are and how they might be conducted. For a deeper understanding it will be essential to read widely.

10.7 References used in this chapter

Dyjack, D. T., Redinger, C. F., & Ridge, R. S. (2003). Health and Safety Management System Audit Reliability Pilot Project. AIHA Journal, 64(6), 785-791. http://www.informaworld.com/10.1080/15428110308984873

Hutchinson, B., Dekker, S., & Rae, A. (2024). Audit masquerade: How audits provide comfort rather than treatment for serious safety problems. Safety Science, 169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2023.106348

ISO9001: 2015 Quality management systems – Requirements, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

Leung, P., Coram, P., Cooper, B., et al. (2015). Modern Auditing & Assurance Services (6th ed.). Wiley.

Martinov-Bennie, N., O’Neill, S., Cheung, A., et al. (2014). Issues in the Assurance and Verification of Work Health and Safety Information [Research Report]. Safe Work Australia, NSW. https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/doc/issues-assurance-and-verification-work-health-and-safety-information

Moroney, R. (2022). Auditing: A Practical Approach. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

O’Neill, S., Cheung, A., & Wolfe, K. (2013). Issues in the assurance and verification of work health and safety information [Review]. Safe Work Australia, NSW. https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/1703/issues-assurance-verification-wh-_information-review.pdf

O’Neill, S., Wolfe, K., & Holley, S. (2015). Performance measurement, incentives and organisational culture:Implications for leading safe and healthy work [Research Report]. Safe Work Australia, NSW. https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/

Wassenaar, B. (2024). Twice as likely to die: The failure of auditing to make an impact on health and safety outcomes in New Zealand. NZ Journal of Health and Safety Practice, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.26686/nzjhsp.v1i2.9513