Preface

Welcome to this book on Achieving acceptable certainty in the workplace. It draws on research, practice and international standards and was developed for people who work in occupational health and safety in New Zealand. It may also help other professionals who need to apply a structured approach to aspects of internal and external consultancy in workplaces.

The journey to this book

Some of the contents of this book mark way stations in my career from 1974 when I started work enforcing the British Health and Safety at Work Act (1974): through managing aspects of safety; consultancy work in insurance and risk management; work as a corporate risk manager; freelancing; expert witness; and now as a lecturer and researcher at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington. I also helped develop New Zealand and joint Australia/New Zealand standards and handbooks and contributed to international standards on risk.

I started that journey with a somewhat deterministic philosophy but little by little doubts crept in. These crystallised with the definition of risk in the first edition of AS/NZS4360 Risk management in 1995. We were dealing with the “chance of something happening that will have an impact on objectives”. Chance and objectives became significant issues.

But then ISO31000: 2009 Risk management was published and adopted in Australia and New Zealand as a replacement for AS/NZS4360. Risk was now defined as the “effect of uncertainty on objectives”, requiring more thought about, and attention to, uncertainty as well as objectives. How much uncertainty are we faced with? Whose objectives should we pay attention to?

As part of my PhD research, I examined the effectiveness of risk assessments in informing decision makers. The result was a little depressing. In my case studies little thought seemed to be given to the meaning of risk and risk assessment, the identification of business objectives and the effect of uncertainty on them, and there seemed to be no structured approach to finding the best available information to inform decisions.

This book also has its origins in undergraduate level papers I taught at Massey University 2004-2012 and two-day short courses I ran 2004-2019. The handouts for that teaching were never subject to a unifying edit to remove overlaps and gaps, and the short courses were not referenced.

The teaching and training resources I developed helped crystallise some of my thinking. Work on two joint Australia/New Zealand standards committees and an International Standards Organization committee added to the depth and breadth of my thinking. I met and debated (sometimes argued) with people who further informed my thinking.

Some of that teaching material inspired parts of my PhD and was then subject to editing and revision. When I started teaching at Victoria University of Wellington in April 2020 (just as the pandemic lockdowns started!) I quickly adapted and revised the old material to create two fully referenced handouts based on ISO31000: 2018 Risk management – guidelines, ISO45001 Occupational health and safety management systems and other standards. But overlaps and gaps remained, and some material had not been properly revised for several years. In early 2021 it was time to merge the two handouts into the first edition of this book. now, for 2025, the whole book has been revised and the graphics refreshed.

A longer timeline

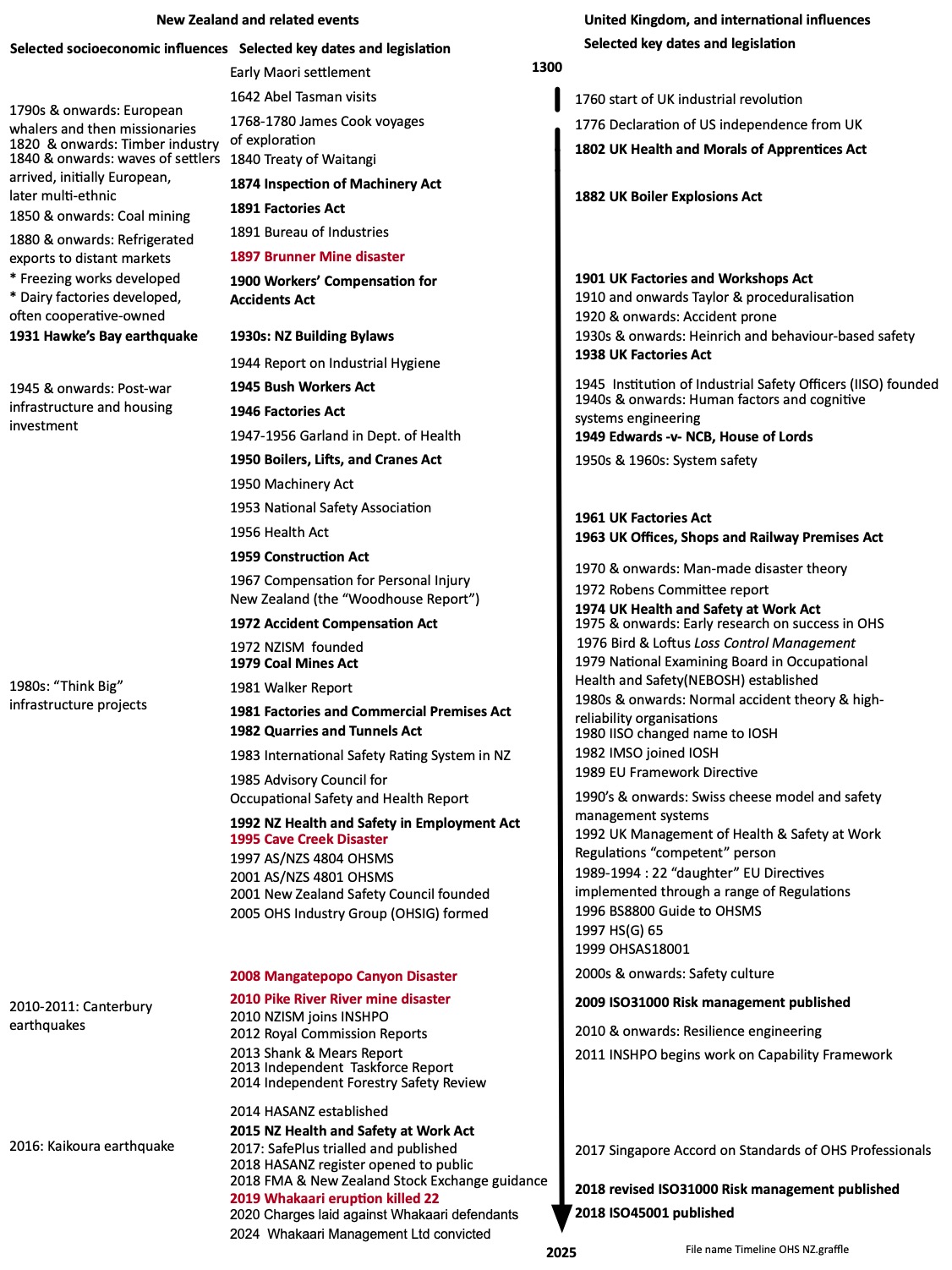

Figure 1 summarises some key events in the development of occupational health and safety (OHS) in New Zealand and elsewhere from 1840 to 2020. Some of the history of occupational health and safety as a profession in New Zealand was summarised by Peace et al (2019) and, for academic students, will fill some gaps.

After 2010 in New Zealand

In occupational health and safety terms New Zealand has come some distance from the time of Te Tiriti o Waitangi in 1840 but our legislation was, until recently, reactive and did not cover all workers in all workplaces. In contrast to the UK (where the 1974 law change was to remove obsolete legislation and replace it with modern law) the New Zealand Health and Safety at Work Act (2015) followed the Pike River tragedy (Macfie, 2021) and subsequent Royal Commission (2012), Independent Taskforce (Jager et al., 2013), and the Shanks & Mears Reports (Shanks & Meares, 2013), plus the Independent Forestry Safety Review (Adams, G. et al., 2014). The NZ Act is closely based on the Australian Model Work Health and Safety Bill (2011) but is ultimately derived from the British Health and Safety at Work Act (1974).

A sea change in thinking about uncertainty and its management

It has increasingly been accepted that managing occupational health and safety requires the identification and management of uncertainty about achieving objectives. The international standard ISO31000 Risk management – guidelines (first published 2009; updated in 2018) defines risk as the “effect of uncertainty on objectives” and is a major theme in this book. A similar change has occurred with the publication of ISO45001 (2018) Occupational health and safety management systems, the topic of the first part of this book.

If uncertainty is to be effectively managed it must be understood; this will require the use of diagnostic management techniques set in the generally accepted risk assessment process described in ISO31000(2018). Some applicable techniques are identified in each chapter and described in Chapter 21 of this book. Many techniques are more fully described in IEC/ISO31010 (2019) Risk assessment techniques and IEC62740 (2015) Root cause analysis.

Hazard, risk, uncertainty and OTIF 95

While revising the content of the book I have tried to minimise use of the words “hazard” and “risk”, instead referring to the causal factors of events and their consequences, and how much certainty there is about achieving objectives. A key takeaway for any risk or safety advisor using this book is to ask colleagues the question: “How sure are you we will achieve that On Time, In Full, 95% of the time?” – OTIF95 for short.

Even better is to coach the CEO to ask the question. Asking managers for the probability of OTIF may start to reveal areas of undue optimism – or systemic weaknesses. OTIF is quite difficult to achieve 95% of the time. When linked with occupational health and safety, quality, or other goals it gives a strong focus on the objectives of organisations. This becomes something tangible to help improve management of a PCBU.

Integration of management systems

Annex SL (ISO/IEC Annex SL, 2020) provides a common framework for management system standards published by the International Standards Organization (ISO). Three standards (ISO9001 Quality management systems, ISO14001 Environmental management systems, and ISO45001 Occupational health and safety management systems) are often used in larger organisations (Zutshi & Sohal, 2005). Integration of the three standards into a single standard could seem a logical step (Labodova, 2004) but this might be difficult within the Standards organisations. However, such management systems could be integrated in a single system within a business or undertaking (Peace, 2024a; Pojasek, 2006; Zutshi & Sohal, 2005), so reducing costs, resulting in a more consistent and harmonised hazard management process (Ferreira Rebelo et al., 2017) and “Total Safety Management” (Kontogiannis et al., 2017). This could be extended to include corporate social responsibility (Asif et al., 2013) using an integrated management systems (IMS) approach, an approach now advocated by the US National Safety Council (National Safety Council, 2023).

Bunn et al. (2001) used a single case study to show how management of safety, workers’ compensation, short-term disability, long-term disability, healthcare, and absenteeism could be integrated, yielding benefits for the employer and workers. Badri et al (2012) showed how the construction industry has tools, methods and approaches that could help integrate OHS with management generally. Finally, changes in employment arrangements have led to precarious employment, often resulting in deterioration of OHS standards. Nossar (2003) proposed a regulatory strategy requiring re-integration of “industrial relations, OHS and workers’ compensation and social security” that can be regarded as a parallel approach to integrated management systems.

Integration in this book

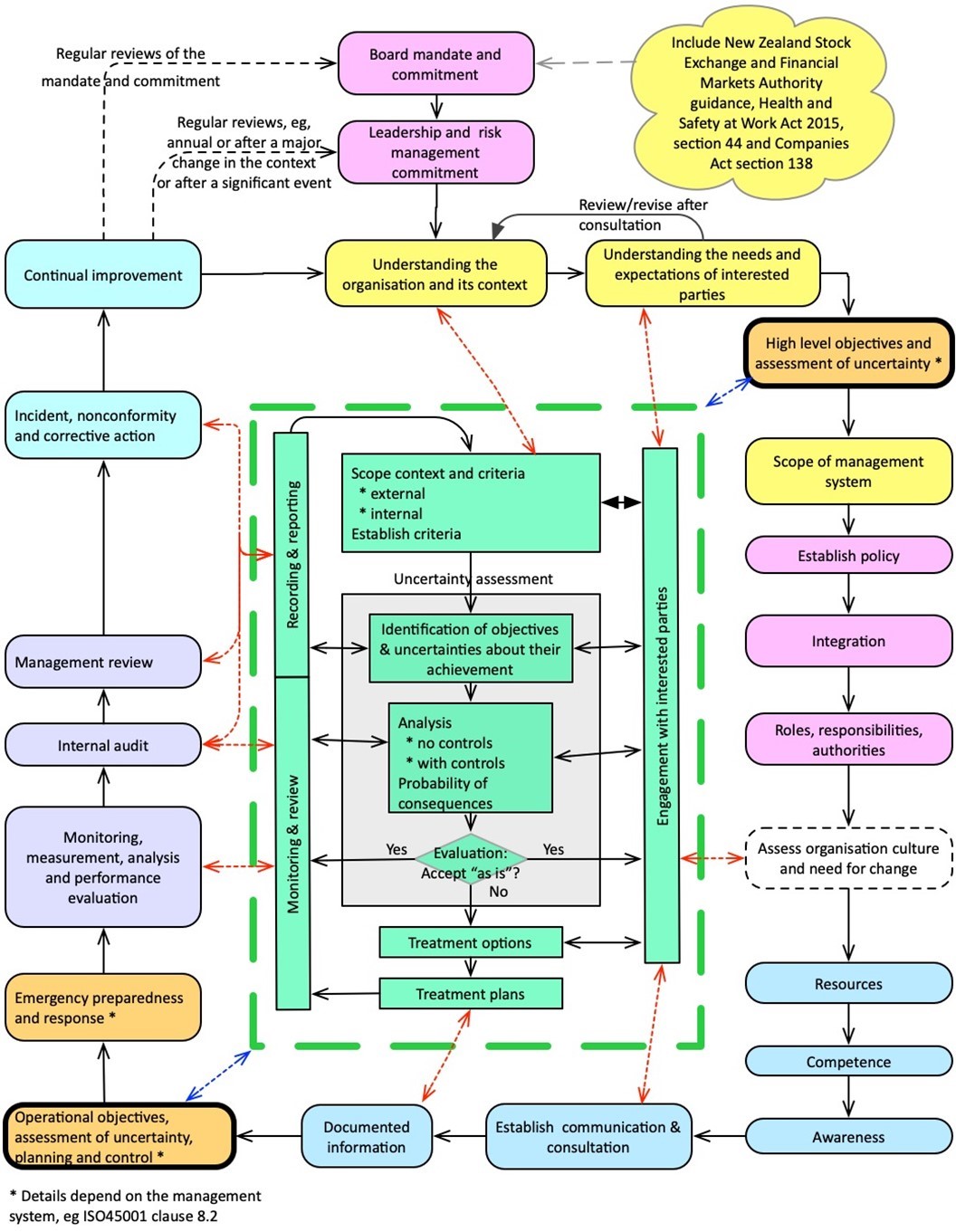

Figure 2 shows the high-level structure in all ISO management system standards and the risk management process in ISO31000. The outer loop is based on the guidance in ISO Annex SL (2020) and is the basis of chapters 1-10 of this book while the central green boxes represent the risk management process covered in chapters 11-20.

Layout and content of the book

I have separated the content of this book into four parts:

Part 1 – Chapters 1-10: Management systems and systems thinking in occupational health and safety

This part introduces management systems relevant to occupational health and safety and how and why they might be integrated.

Part 2 – Chapters 11-20: Understanding, assessing, and managing uncertainty in PCBUs

This part introduces uncertainty (risk) and its assessment, leading what my friends and mentors Roger Estall and Grant Purdy call “sufficient certainty” about achieving business objectives.

Part 3 – Chapter 21: A to Z of useful management techniques, including writing

This chapter presents techniques that an OHS professional should know of and how to use some to help find information or diagnose problems.

Part 4 – Chapter 22: A glossary of many terms commonly defined in standards and legislation

This short chapter offers definitions of terms used in some standards and legislation referred to in this book.

This structure of the book allows for expansion to include other major topic areas, one of which (Incident Investigation) is under development with a colleague and may become a fifth part and a new paper.

References cited within each chapter are listed in a bibliography at the end of each chapter.

The law and legal decisions

New Zealand legislation and court cases on OHS are cited throughout this book. However, legislation, and cases from other jurisdictions (eg, Australia, Canada and Britain) that might be important to managing work health and safety in New Zealand workplaces are also included.

Who might use this book?

This book will be used by our students at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington to help their studies in the Master of Health in Work Health and Safety programme. I hope it will also be of help to our graduates when they work as practitioners, professionals, and managers, and to teachers and students elsewhere.

While the current edition is still a work in progress, it is fully referenced and maps against the two papers I teach; it also has some material in common with other papers that my colleagues teach. An import file for Endnote contains much grey literature and can be downloaded from the Victoria University of Wellington library.

This book incorporates many of the technical and supporting skills set out in the International Network of Safety and Health Practitioner Organisations capability framework (INSHPO, 2017) and the Institution for Occupational Safety and Health Professional Standards (IOSH, 2019), and also responds to the requirements for health and safety generalists published by the Health and Safety Association NZ (2022), and the New Zealand Institute for Safety Management (NZISM) and New Zealand Safety Council (NZSCP).

Acknowledgements

Three people have been especially influential to my thinking, work, and research.

Vicky Mabin was one of my PhD supervisors and introduced me to the Goal Tree, changing how I view organisations and objectives.

Grant Purdy (who I met when he was the chair of the joint standards committee on risk management) and Roger Estall (who was my manager for five years in the 1980s, and who was also on that joint standards committee) provoked and informed my thinking about risk. Sadly, Roger died in 2023. We didn’t agree on some things (and I have no doubt this book would have provoked some reactions!), but we agreed about the importance of uncertainty.

My thanks to Selena Armstrong who, when the CEO of the New Zealand Institute of Safety Management (NZISM) asked me to present webinars for members using the fact or fiction theme.

I also thank my wife, Ruth Brassington, for her professional editorial assistance. Ruth has clarified my writing and made invaluable suggestions about the structure of the book.

Thanks also to Philip Worthington, a Subject Librarian at Victoria University Library | Te Pātaka Kōrero, who leads the Open Educational Resources Working Group . Philip first approached me in June 2021 about writing this book and has supported and assisted me in numerous ways since, with copyright permissions, converting to Pressbooks, and helping refine drafts of this book. Philip recruited Mary Cobelbick to copyedit my manuscript, thank you Mary.

Important points

Navigating this book

- clause refers to part of a standard or Annex SL

- section refers to a part of this book or part of an Act of Parliament

- paragraph refers to a paragraph in a District Court or High Court decision or part of a Regulation.

Models

Many of the graphics in this book can be thought of as models. However: “It has been said that ‘all models are wrong but some models are useful’ In other words, any model is at best a useful fiction – there never was, or ever will be, an exactly normal distribution or an exact linear relationship. Nevertheless, enormous progress has been made by entertaining such fictions and using them as approximations.” (Box & Luceño, 1997, p. 6).

Some models help us move from between theory and practice and vice versa (Morrison & Morgan, 1999). Put another way, use my graphics as models to help understand the real world.

Copyright

All graphics, figures, photographs and tables are Copyright © Chris Peace unless otherwise stated.

Cover image

The cover image is Ngā Mokopuna (formerly the Living Pā) under construction.

Feedback and improvements

This book will be revised annually at the end of calendar years but your feedback, comments and suggestions for improvement are welcome at any time.

I hope this book will contribute to a reduction in workplace deaths, injuries, and damage to assets.

Chris Peace

Wellington

January 2025

christopher.peace@vuw.ac.nz

References in the preface

Adams, G., Armstrong, H., & Cosman, M. (2014). Independent Forestry Safety Review. http://cosmanparkes.co.nz/

Asif, M., Searcy, C., Zutshi, A., et al. (2013). An integrated management systems approach to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Cleaner Production, 56, 7-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.10.034

Badri, A., Gbodossou, A., & Nadeau, S. (2012). Occupational health and safety risks: Towards the integration into project management. Safety Science, 50(2), 190-198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2011.08.008

Box, G., & Luceño, A. (1997). Statistical Control By Monitoring and Feedback Adjustment. Wiley.

Bunn, W. B. I., Pikelny, D. B., J. Slavin, T., et al. (2001). Health, Safety, and Productivity in a Manufacturing Environment. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 43(1), 47-55. http://journals.lww.com/joem/Fulltext/2001/01000/Health,_Safety,_and_Productivity_in_a.10.aspx

Ferreira Rebelo, M., Silva, R., & Santos, G. (2017). The integration of standardized management systems: managing business risk. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 34(3), 395-405. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQRM-11-2014-0170

HASANZ. (2022). An Overview of Health & Safety Generalist Careers in New Zealand [Information Paper]. Health and Safety Association of Zealand, Wellington. https://www.hasanz.org.nz/

Health and Safety at Work Act (2015). New Zealand http://www.legislation.govt.nz/

Health and Safety at Work etc Act (1974). Great Britain http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1974/37

IEC62740: 2015 Root cause analysis (RCA), International Electrotechnical Commission, Geneva. https://www.standards.govt.nz/

IEC/ISO31010: 2019 Risk management – Risk assessment techniques, International Electrotechnical Commission,, Geneva.

INSHPO. (2017). The Occupational Health and Safety Professional Capability Framework: A Global Framework for Practice [Standard]. International Network of Safety and Health Practitioner Organizations, Park Ridge, Il, USA. https://www.inshpo.org/

IOSH. (2019). Professional standards for safety and health at work: competency framework [Standard PS07068]. Institution of Occupational Safety and Health, Wigston, UK. www.iosh.com

ISO31000: 2009 Risk management – Principles and guidelines, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

ISO31000: 2018 Risk management – Guidelines, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

ISO45001: 2018 Occupational health and safety management systems: Requirements with guidance for use, International Standards Organization, Geneva.

ISO/IEC Annex SL. (2020). Proposals for management system standards. In Directives, Part 1: Consolidated ISO Supplement – Procedures specific to ISO (11th ed.). International Standards Organization. https://www.iso.org/directives-and-policies.html

Jager, R., Cosman, M., Mackay, P., et al. (2013). Independent Taskforce on Workplace Health & Safety. Wellington. www.hstaskforce.govt.nz

Kontogiannis, T., Leva, M. C., & Balfe, N. (2017). Total Safety Management: Principles, processes and methods. Safety Science, 100, 128-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2016.09.015

Labodova, A. (2004). Implementing integrated management systems using a risk analysis based approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 12(6), 571-580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2003.08.008

Macfie, R. (2021). Tragedy at Pike River mine: how and why 29 men died (2nd ed.). Awa Press.

Model Work Health and Safety Bill (2011). Australia http://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/

Morrison, M., & Morgan, M. (1999). Models as mediating instruments. In M. Morgan & M. Morrison (Eds.), Models as mediators: perspectives on natural and social science (pp. 10-37). Cambridge University Press.

National Safety Council. (2023). The New Value of Safety and Health in a Changing World [Executive Summary]. Author, https://www.nsc.org/workplace/resources/new-value-of-safety?

Nossar, I., Johnstone, R., & Quinlan, M. (2003). Regulating supply-chains to address the occupational health and safety problems associated with precarious employment: The case of home-based clothing workers in Australia [Working Paper wp21]. Australian National University, Canberra. www.http://ohs.anu.edu.au/

Peace, C. (2024a). Integrating management systems in the energy sector: the case of the electricity industry in New Zealand. NZ Journal of Health and Safety Practice, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.26686/nzjhsp.v1i1.8680

Peace, C., Lamm, F., Dearsly, G., et al. (2019). The evolution of the OHS profession in New Zealand. Safety Science, 120, 254-262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2019.07.005

Pojasek, R. B. (2006, Winter2006). Is your integrated management system really integrated? Environmental Quality Management, 16(2), 89-97. https://doi.org/10.1002/tqem.20124

Royal Commission on the Pike River Coal Mine Tragedy. (2012). [Enquiry Report Volume 2]. Wellington. www.pikeriver.royalcommission.govt.nz

Shanks, D., & Meares, J. (2013). Pike River Tragedy [Investigation Report]. Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, Wellington. http://www.mbie.govt.nz/

Zutshi, A., & Sohal, A. S. (2005). Integrated management system: The experiences of three Australian organisations. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 16(2), 211-232. https://doi.org/10.1108/17410380510576840

Image descriptions

Figure 1. Development of thinking about safety as a science – image description

This figure is a dual-column timeline comparing the development of occupational health and safety (OHS) science and legislation in New Zealand (left column) and in the United Kingdom/international contexts (right column), from the 1300s to the 2020s. Each column is organized chronologically from top to bottom, with key events grouped by decade and contextual influences included.

Each side includes:

- Italicised text for socioeconomic influences

- Bold text for legislation and regulatory milestones

- Red text for notable disasters or incidents that significantly impacted policy

New Zealand and Related Events Timeline (Left Side)

Selected Socioeconomic Influences

- 1790s onwards: Arrival of European whalers and missionaries.

- 1820 onwards: Timber industry development.

- 1840 onwards: Multi-ethnic settler society emerges post-Treaty of Waitangi.

- 1850 onwards: Expansion of coal mining.

- 1880 onwards: Refrigerated exports promote global trade; cooperative dairy development noted.

Legislation and Regulatory Milestones

- 1840: Treaty of Waitangi.

- 1874: Inspection of Machinery Act — early industrial safety regulation.

- 1891: Factories Act.

- 1900: Workers’ Compensation for Accidents Act.

- 1930s–1950s: Series of safety-related reports and acts:

- 1935: Health Act

- 1945: Bush Workers Act

- 1946: Factories Act

- 1950: Boilers, Lifts, and Cranes Act

Significant Incidents and Their Consequences (New Zealand)

- 1897: Brunner Mine Disaster — over 60 fatalities; led to calls for regulatory reform.

- 2008: Mangatepopo Canyon Disaster — raised questions around risk management in outdoor education.

- 2010: Pike River Mine Disaster — catalyzed national OHS overhaul.

- 2019: Whakaari Eruption — 22 deaths; legal action followed.

National Safety System Maturation and Reform

- 1970s–1980s: Establishment of NZISM (1972), Coal Mines Act (1979), and advisory councils.

- 1992: Landmark Health and Safety in Employment Act.

- 1995–2001: Standards development (e.g., AS/NZS 4801 OHSMS).

- 2015: Health and Safety at Work Act post-Canterbury earthquakes.

- 2017–2024: Ongoing implementation of standards, public guidance, sentencing, and safety registries.

UK and International Timeline (Right Side)

Industrial and Legislative Origins

- 1760: Start of UK Industrial Revolution.

- 1802: Health and Morals of Apprentices Act — earliest factory legislation.

- 1882: UK Boiler Explosions Act — safety response to industrial risks.

Workplace Reform Milestones

- 1901–1938: Expansion of UK factory and safety acts:

- 1901: UK Factories and Workshops Act

- 1938: UK Factories Act

- 1945: Founding of Institution of Industrial Safety Officers.

- 1949: Edwards v. National Coal Board — pivotal case that established the principle of “reasonably practicable” risk mitigation, a key standard in modern safety law.

Modern Safety Systems

- 1961–1974: Regulatory foundations developed:

- 1974: UK Health and Safety at Work Act

- 1980–1990s: Introduction of systems thinking (Swiss Cheese Model, NEBOSH).

- 1992: UK Management of Health & Safety at Work Regulations — defined “competent person.”

- 1996–1999: Global standards introduced (BS8800, HS(G)65, OHSAS18001).

Recent Developments

- 2000s onwards: Emphasis on safety culture, resilience engineering, and ISO standards:

- 2009: ISO31000 Risk Management

- 2018: ISO45001 published — global OHS benchmark.

Visual Cues Enhancing Understanding

- Red text: Indicates major disasters or fatal incidents that had a significant impact on OHS policy or public awareness.

- Bold text: Used for acts, legislation, and official standards to distinguish legal or structural developments.

- Italic text: Denotes broader socioeconomic or cultural influences shaping policy and industrial change.

- Two-column layout: Allows parallel tracking of local (New Zealand) and external (UK/international) developments for comparative understanding.

- Chronological flow: Events are ordered top-to-bottom within each column by decade or thematic phase to show progression.

This timeline highlights the parallel but interconnected development of workplace safety science in New Zealand and globally, showing how major incidents and international legal principles — like the “reasonably practicable” standard — influenced domestic legislation and thinking.