2 Ancient history activities

1. Socratic seminar: What is a civilisation?

Nicholas Reynolds

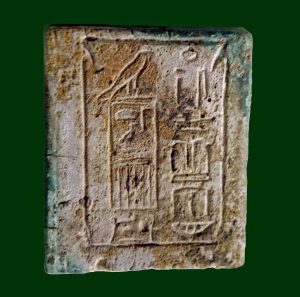

Cuneiform Tablet by Medelhavsmuseet (Europeana) CC BY-NC-ND 2.5

| Curriculum context | Unit 1: Ancient History (VCAA, 2020) |

| Historical thinking concept/s | Ask and use historical questions |

| Historical context | Ancient Mesopotamia > Discovering Civilisation > Features of Civilisation |

| Learning intentions | Identify the key features of Ancient Mesopotamia and how these reflect the designation ‘The Cradle of Civilisation.’

Hone independent research skills. Understand the complexities of the word ‘civilisation’ and why it is considered a contentious term. Engage in collaborative discussion. |

Activity

For this activity, you will work either individually or in small groups in order to research a list of questions revolving around the concept of ‘civilisation’, and the relevance of ancient Mesopotamia on the development of ‘civilisation’ (VCAA 2020: 31). Make sure to write at least several lines in response to each question, citing sources where relevant. While you should utilise the sources given, you are also encouraged to read more broadly.

After the research session, the class will come together and hold a Socratic seminar prompted by a question about the term ‘civilisation’ and Ancient Mesopotamia. Students will facilitate the discussion, and as a group we will ensure that it is a safe, open space is created to explore ideas. Once we finish the seminar, you will reflect on the questions and ideas raised through this process.

Part 1: Preparing for a Socratic seminar

Research prompts:

- Where does our concept of ‘civilisation’ come from?

- What are considered to be the pillars of civilisation?

- What are some problems with the term ‘civilisation’?

- What are the elements of Ancient Mesopotamia that seemingly make it ‘The Cradle of Civilisation’?

- Where is Mesopotamia geographically? How and why is that relevant to its development as a civilisation?

- What are some examples of other ancient societies which may be neglected by these definitions of ‘civilisation’?

Information sources:

- National Geographic: Civilizations

- Kids Britannica: Civilization

- Britannica: Civilization

- The Conversation: The concept of ‘Western civilisation’ is past its use-by date in university humanities departments

- The Conversation: Friday essay: the recovery of cuneiform, the world’s oldest known writing

Part 2: Socratic Seminar

Question prompt: ‘Do you think writing, building and agriculture are the elements that make Mesopotamia a civilisation?’

Further questions to prompt discussion:

- What instead makes a ‘civilisation’?

- Why do you think Western definitions of ‘civilisation’ may be problematic, especially from the perspective of First Nations and other Indigenous societies?

- Do you think that Mesopotamian myths and stories may give us a better insight into ancient Mesopotamian societal perspectives?

References

Britannica (n.d.) Civilization, Britannica, accessed 21 August 2022.

Coleborne C (21 November 2017), The concept of ‘Western civilisation’ is past its use-by date in university humanities departments, The Conversation, accessed 21 August 2022.

Facing History & Ourselves (n.d.) Socratic Seminar, Facing History & Ourselves, accessed 21 August 2022.

Kids Britannica (n.d.) Civilization, Britannica, accessed 21 August 2022.

National Geographic (n.d.) Civilizations, National Geographic, accessed 21 August 2022.

Pryke L (6 October 2017), Friday essay: the recovery of cuneiform, the world’s oldest known writing, The Conversation, accessed 21 August 2021.

VCAA (Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority) (2020) VCE History Study Design, Victorian Government, accessed 21 August 2022.

2. The Epic of Gilgamesh: Research and develop a creative response

Nicholas Reynolds

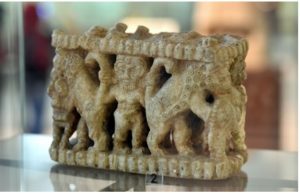

Sculpted scene depicting Gilgamesh wrestling with animals, National Museum of Iraq by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg) CC BY-SA 4.0

| Curriculum context | Unit 1: Ancient History (VCAA, 2020) |

| Historical thinking concept/s | Explore historical perspectives |

| Historical context | Ancient Mesopotamia > Discovering Civilisation > Social, Political and Cultural Features |

| Learning intentions | Develop an understanding of ancient perspectives, including the social, political and cultural features of Mesopotamian society.

Explore the way primary sources can be used to extract evidence about not just artistry, but also ancient perspectives. Draw connections between Mesopotamian myths and other cultures’ stories, and why those connections may exist. |

Activity

Through the study of the ancient Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh this activity asks you to examine how myths, narratives and storytelling give insight into people’s perspectives, societal beliefs and in ancient times. Each small group will be given an excerpt from David Ferry’s translation of either Tablet I or Tablet XI, and asked to answer a list of questions.

Once you have briefly presented your findings to the class, you will be asked to compose a 300-word equivalent creative piece from the perspective of one of the characters from the Epic, accompanied by a 50-150 word rationale explaining what historical aspects and perspectives informed your piece.

Part 1: Research

Working in groups, read the excerpt from David Ferry’s translation of ‘The Epic of Gilgamesh’. Remember that these are recent English translations of the ancient Bablyonian tablets (from circa 1,800 BCE) – try and compare the differences between the two translations. Once you have read them, answer the questions as a group.

Also look at the article Guide to the classics: the Epic of Gilgamesh from The Conversation, it has some great notes about the relevance of these myths in Mesopotamian society to help guide your responses.

- Tablet One, Excerpts i-iii: translation

- Tablet One, Excerpt iv: translation

- Tablet Eleven, Excerpts i-iii: translation

- Tablet Eleven, Excerpts iv-vi: translation

- Tablet Eleven, Excerpts vii-ix: translation

- Alternative translation

Questions

- What is the relevant theme, message or moral of your excerpt?

- What insight does the story give us about Ancient Mesopotamian society and the development of ‘civilisation’? Do you think everyone would have agreed?

- What translational biases might it hold?

- Is there any Mesopotamian art which may help to enrich your understanding of the story? How? (Hint – there are some relevant pictures attached below!)

- Can you think of another story (myth, parable, fable or modern) which shares aspects with this story? Do you think that connection is convergent or divergent?

Research prompt images

Image 1: Gilgamesh Sculpture by Kadumago, Wikipedia Commons CC-BY-4.0

Image 2: Votive Relief by Royal Museums of Art and History, Brussels, Belgium (Europeana) CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0

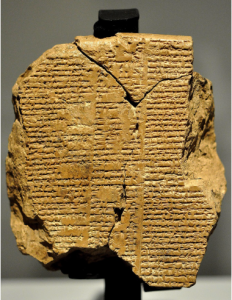

Image 3: Tablet V of The Epic of Gilgamesh by Dr. Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin, Wikipedia CC-BY-SA-4.0

Part 2: Presenting findings

As a group, present a short presentation of your group’s answers to the rest of the class. Remember, you all have different parts of the story, so make sure to give a quick recap of your part of the narrative. Help your classmates by explaining the links and connections to Mesopotamian society – what does your story teach us about the ancient society?

Part 3: Creative response

Now you will compose a short 300-word equivalent creative response (of your choice – story, poem, image, song etc) from the perspective of one of the characters from your excerpt. In the work, utilise the social and cultural understanding of Mesopotamia you have developed, including Ancient Mesopotamian perspectives you’ve utilised. For example, what does your character think of the afterlife? Do they prefer the wilds to the Mesopotamian cities? These findings may be more thematic than literal–utilise your creativity! This should be accompanied by a 50-150 word rationale in which you explain how you’ve used your research to present realistic ancient perspectives of Mesopotamian society.

References

Pryke L (8 May 2017), Guide to the classics: the Epic of Gilgamesh, The Conversation, accessed 22 August 2022

Ferry D (n.d.) Gilgamesh: Tablet 1, The Poetry Foundation, accessed 22 August 2022

Type your textbox content here.Ferry D (n.d.) Gilgamesh: Tablet 11, The Poetry Foundation, accessed 22 August 2022

Jason and the Argonauts Through the Ages (n.d.) The Epic of Gilgamesh: Translated by William Muss-Arnolt 1901, Jason and the Argonauts Through the Ages, accessed 22 August 2022

3. Religion, power, and the pharaohs: A timeline of change

Brittany Bell

Procession from the Temple of Amun by Metropolitan Museum of Art, picryl Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0) Public Domain Dedication.

| Curriculum context | Unit 2: Ancient Egypt (VCAA, 2020) |

| Historical thinking concept/s | Analyse cause and consequence |

| Historical context | Changes in religious beliefs and practices, power, and representation during the time of Middle Kingdom Egypt and Second Intermediate Period |

| Learning intentions | Identify key moments of change during Middle Kingdom Egypt and the Second Intermediate Period.

Create a timeline to demonstrate knowledge of the periods. Work collaboratively to create a group resource. |

Activity

Individual activity:

Find out about and build a timeline of important people, events, and change. Your focus is on religion, religious practices, and the role of the Pharaohs during the following two Egyptian periods:

- Middle Kingdom Egypt 2040 – 1782 BCE

- Second Intermediate Period 1782 – 1570 BCE

Your timeline can be on paper or created digitally. For each point on the timeline, you need to include:

- Heading

- Dates or date range

- Source of evidence (try using the following sources for pictures)

- Resources at Digital Egypt for Universities

- Middle Kingdom (2025-1700 BC)

- Egypt in the Second Intermediate Period (about 1700-1550 BC)

- Online Collections by Penn Museum

- Resources at Digital Egypt for Universities

Whole class activity:

Once your timeline has been created, you will be working together with the class to make a timeline incorporating everyone’s research. Using the class timeline, update your own with any missing information so you can use it in the next activity.

You could use the following resources as part of your research:

Resources by World History Encyclopedia

Middle Kingdom of Egypt Timeline

Second Intermediate Period of Egypt

Second Intermediate Period of Egypt Timeline

An Introduction to the Ancient Egyptian Civilization

Timestamp 2:45 Middle Kingdom Egypt

Timestamp 4:49 Second Intermediate Period

Resources by The Australian Museum

Here are some key people and words to get you researching:

Senwosret II (also Senusret II), Senwosret III (also Senusret III), Sesostris, Amenemhat III, Amun, Osiris, Isis, 12th Dynasty, 13th Dynasty, Hyksos, Herakleopolis, Thebes, Iti-tawi, Karnak, Nubia

References

Ancient History Encyclopedia (8 October 2020) ‘An Introduction to the Ancient Egyptian Civilization’, World History Encyclopedia, YouTube, accessed 25 July 2022.

The Australian Museum (14 May 2021) Ancient Egyptian Timeline, The Australian Museum, New South Wales Government, accessed 25 July 2022.

Mark JJ (4 October 2016) Middle Kingdom of Egypt, World History Encyclopedia, accessed 25 July 2022.

Mark JJ (5 October 2016) Second Intermediate Period of Egypt, World History Encyclopedia, accessed 25 July 2022.

Penn Museum (n.d.) Online Collections, Penn Museum, accessed 25 July 2022.

University College London (n.d.) Middle Kingdom (2025-1700 BC), University College London, accessed 25 July 2022.

University College London (n.d.) Egypt in the Second Intermediate Period (about 1700-1550 BC), University College London, accessed 25 July 2022.

World History Encyclopedia (n.d.) Middle Kingdom of Egypt Timeline, World History Encyclopedia, accessed 25 July 2022.

World History Encyclopedia (n.d.) Second Intermediate Period of Egypt Timeline, World History Encyclopedia, accessed 25 July 2022.

VCAA (Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority) (n.d.) Teaching and learning activities, VCAA, Victorian Government, accessed 25 July 2022.

VCAA (Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority) (2020) VCE History Study Design, VCAA, Victorian Government, accessed 11 July 2022.

4. How cause and consequence shaped Middle Kingdom Egypt and the Second Intermediate Period

Brittany Bell

Apotropaic rod, Egypt, Middle Kingdom, 2040 – 1640 BC by Metropolitan Museum of Art, picryl. Available under Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0) Public Domain Dedication.

| Curriculum context | Unit 2: Ancient Egypt (VCAA, 2020) |

| Historical thinking concept/s | Analyse cause and consequence |

| Historical context | Changes in religious beliefs and practices, power, and representation during the time of Middle Kingdom Egypt and Second Intermediate Period |

| Learning intentions | Demonstrate knowledge of key moments during Middle Kingdom Egypt and the Second Intermediate Period.

Identify and contextualise the links between timeline events and their causes and consequences. Evaluate the impacts of cause and consequence for the people of the time. |

Activity

In this activity you will use the timeline you developed in the last activity to analyse cause and consequence of events during Middle Kingdom Egypt and the Second Intermediate Period.

In groups of 3 – 4, you will work together to explain and document the cause between each stage of your timeline and the consequences that occurred for the Ancient Egyptian people. You will need to critically think about each of these points on your timeline and analyse the how, when, where, why and what.

Considering different groups of people during the time will provide examples of consequences shaped by different the perspectives. For example, would a change of religion or religious practice impact the ruling class and slaves differently?

Cause and consequence analysis

As part of your group’s analysis

- Use a fishbone diagram template to consider each stage of your timelines

- You will need to complete 4 fishbone diagrams to analyse different points along your timeline. If you have extra time keep going!

- Write the consequence you identify on the left and ask your questions along the branches.

Group Work

Working in groups is a great opportunity to hear other people’s thoughts and discuss viewpoints you may not have considered. When working in a group it may be helpful for your group to give each member a role to keep everyone on track. Suggested roles for this activity are:

- Facilitator (keep everyone on track and keep the conversation moving)

- Recorder (fill in the fishbone diagrams on behalf of your group)

- Researcher (research additional information to support group discussion)

- Researcher (research additional information to support group discussion)

See the below prompts to get you started in your discussion:

- The role of the pharaoh

- Who were the pharaohs of the time? What was their line of succession?

- What are they remembered for?

- Did their actions have long or short-term consequences?

- Representation of power

- How did the pharaohs or ruling class wield their power?

- Who gained benefits when power changed hands?

- How did different groups of people respond to changes in power?

- Location of the ruling class

- Did this change during the periods? Why?

- What impacts did this have on different groups of people?

- Changes in religion or religious practices

- Why did religion change? How does this happen and who was involved?

- Is there any development of a dominant god or gods?

- How does this change influence the religious practices of the people?

References

Commonwealth of Australia (n.d.) Fishbone Diagram, Global Education Website, accessed 26 July 2022.

Facing History & Ourselves (n.d.) Assigning Roles for Group Work, Facing History & Ourselves, accessed 26 July 2022.

VCAA (Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority) (2021) VCE History Study Design, VCAA, Victorian Government, accessed 11 July 2022.

5. Exploring ancient Egypt: A tour of the past

Nicolette Arranga

Sphinx Pyramid, Egypt. by JMA659, Pixabay License

| Curriculum context | Unit 2: Ancient Egypt (VCAA, 2020) |

| Historical thinking concept/s | Establish and evaluate historical significance |

| Historical context | Ancient Egypt, Old Kingdom |

| Learning intentions | Locate and select a natural or architectural feature of Ancient Egypt and evaluate its geographical, political, social, religious and symbolic significance.

Compare the significance of the feature in ancient times compared to its perceived importance in the present. |

Activity

PART 1: Research

Locate and research a significant natural or architectural feature of Ancient Egypt. Examples include the Nile delta or specific architectural features of the pyramids of Djoser and Meidum, the Pyramid Texts, pyramid fields at Dashur and the complex of Dynasty VI at Giza, cemeteries of Saqqara, Giza and Dahshur.

Use the following table to guide your note-taking:

NOTE-TAKING GUIDE

General information

Identify general facts or information.

Geographic significance:

What is the significance of its location? Is it in the centre of what was Ancient Egypt? Does it face a certain direction?

Political significance:

Did the feature have a place in politics? Was it the location of a court?

Social significance:

Did all of society value this feature? Was it special only to the rich and royal? Who could access it?

Religious significance:

Did this feature represent a religious deity? What beliefs are associated with it?

Symbolic meaning:

Is there a symbolic meaning behind this feature? Does it represent life, death, or power?

Significance in the present:

Does the feature still exist today? How has it changed or stayed the same? What is its historical significance in the present? What is its heritage status?

You might like to use the NAME acronym: Novelty, Applicability, Memory, Effects (History Skills, 2022) to develop further questions based on these criteria.

Synthesising your research: Drawing on your research, write a response to the following question: To what extent has the historical significance of this feature developed since it was used in the period of the Old Kingdom?

PART 2: Virtual tour

Plan your virtual tour

Now you have done some research you are going to imagine you are a tour guide in Egypt today and your task is to take another person in the class on a virtual tour of this feature. You will guide your visitor around the site using photos and descriptive details. You can include up to two minutes of video footage without audio but you must provide the commentary.

- The sources you use must be questioned for context, content, and authorship. Try your best to locate and use copyright appropriate material that you have permission to reproduce.

- Be sure that the images you are using are linked to a historical context. For example, if there is a photograph of your feature, make sure you list when the photograph was taken.

- Have a look through at Google Arts and Culture example of a Virtual Tour.

- You will have to tell your tourist about the reasons why the feature was religiously, socially, politically, geographically and symbolically significant at the time and the extent that it is considered historically significant today, and by whom.

Take a tour and give a tour

You will have the opportunity to take someone on a tour and go on their tour. When you are taking a tour you need to ask questions that relate to finding out more about the historical significance of the feature.

References

Google Arts and Culture (2022) Masterpieces of ancient Egyptian art and architecture explained. Google Arts and Culture, accessed 6 September 2022.

History Skills (2022) Historical significance explained. History Skills, accessed 6 September 2022.

VCAA (Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority) (2021) VCE History Study Design, VCAA, Victorian Government, accessed 6 September 2022.

6. Developing inquiry questions about the Old Kingdom

Remi Donnison

Plate of Horus Netjerkhau (Pepi II), with the mention of the 1st “Heb Sed” (Jubilee feast) of the King, Egyptian Museum, Cairo by Juan R. Lazaro, Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)

| Curriculum context | Unit 2: Ancient Egypt (VCAA, 2020) |

| Historical thinking concept/s | Ask and use historical questions

Use sources as evidence |

| Historical context | The Double Crown: Kingship in Old Kingdom Egypt from the Early Dynastic Period (2920 BCE) concluding at the end of the First Intermediate Period (2040 BCE). |

| Learning intentions | Analyse artefact from the old Kingdom.

Develop a historical question based on the source analysis and research the answer.

|

Activity

Step 1: View this image of a statue from the Old Kingdom.

Step 2: Analyse the image by answering the following questions:

1. What do you see in this image?

2. Who is the pharaoh? Give two reasons to explain how you know?

3. Who is the other person in the image?

4. What is the historical context or time period of the statue?

Step 3: Create your inquiry question

With the information you have gathered from your analysis, create a questio about power dynamics in the Old Kingdom of Egypt that interests you. You can use some of the following key words to help create your question.

- power dynamics

- Old Kingdom

- pharaoh

- causes

- consequences

- archaeological discoveries

- nomarchs

- Memphis

- wealth

- relationships

- bureaucracy

Step 4: Answer your inquiry question.

References

VCAA (Victorian Curriculum Assessment Authority) (2020) Victorian Certificate of Education, History Study Design: Accreditation Period 2022-2026, VCAA, Victoria State Government, accessed 20 July 2022.

Gobetz W (13 April 2008) NYC: Brooklyn Museum- Statue of Queen Ankhnes-meryre II and her son, King Pepy II [image], flickr, accessed 4 September 2022. Available under Attribution-NonCommerical-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

7. Primary source analysis (part 1): Slavery in ancient Rome

Anna Griffiths

Roman Colosseum by Ichigo121212 Pixabay License

| Curriculum context | Unit 1: Investigating the Ancient World (QCAA, 2018) |

| Historical thinking concept/s | Source analysis |

| Historical context | Roman society (753–133 BCE) |

| Learning intentions | Analyse one primary source to identify explicit and implied/inferred information, and connect this information to prior knowledge.

Evaluate one primary source for reliability and usefulness. |

Activity

You have been given one of the primary sources below (an excerpt from a book, play or document) and may choose to work individually, or in pairs or small groups with students allocated the same primary source. There are two tasks to complete to analyse the source.

Task 1:

From your primary source, identify:

- THREE explicit (clearly expressed) ideas

- TWO implicit or inferred (indirectly expressed) ideas

- ONE connection to prior knowledge

Task 2:

- You may need to research your source and its author to complete Task 2.

- You can structure your response to Task 2 using dot points, a table, sentences, subheadings, or another format you prefer.

- You can record your responses in your workbook or digitally.

Analyse your primary source to determine its:

Origin

- What kind of source is it?

- Who created this source?

- What historical events are likely to have influenced the creation of this source? Why and/or how did these events influence the source?

Perspective

- What point of view does the source present?

- Why and/or how is that point of view presented?

Context

- When was the source created?

- Was the source created during or after the period and events it depicts?

Audience

- Who is the source’s intended audience?

- How would the audience have accessed the source?

Motive

- Why was this source created?

- What is the author/creator’s motive in creating the source?

SOURCE 1

Twelve Tables, c. 450 BCE, Excerpts mentioning slaves

Table VI. Ownership and Possession

- When one makes a bond and a conveyance of property, as he has made formal declaration so let it be binding.

Table VII. Property

- If one has maimed a limb and does not compromise with the injured person, let there be retaliation. If one has broken a bone of a freeman with his hand or with a cudgel, let him pay a penalty of three hundred coins If he has broken the bone of a slave, let him have one hundred and fifty coins. If one is guilty of insult, the penalty shall be twenty-five coins.

- A slave is ordered in a will to be a free man under this condition: “if he has given 10,000 asses to the heir”; although the slave has been alienated by the heir, yet the slave by giving the said money to the buyer shall enter into his freedom..

Table VIII. Offences

- If one has maimed a limb and does not compromise with the injured person, let there be retaliation. If one has broken a bone of a freeman with his hand or with a cudgel, let him pay a penalty of three hundred coins If he has broken the bone of a slave, let him have one hundred and fifty coins. If one is guilty of insult, the penalty shall be twenty-five coins.

- In the case of all other … thieves caught in the act freemen shall be scourged and shall be adjudged as bondsmen to the person against whom the theft has been committed provided that they have done this by daylight and have not defended themselves with a weapon; slaves caught in the act of theft …, shall be whipped with scourges and shall be thrown from the rock; but children below the age of puberty shall be scourged at the praetor’s decision and the damage done by them shall be repaired.

Table XII. Supplementary Laws

- If a slave shall have committed theft or done damage with his master’s knowledge, the action for damages is in the slave’s name.

Reference

From: Thatcher OJ (ed) (1901), The Library of Original Sources, Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 9-11, Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co.

Scanned by: Arkenberg JS, Department of History, California State Fullerton. Prof. Arkenberg has modernized the text.

Collection: Halsall P (1996) ‘Ancient History Sourcebook: The Twelve Tables c. 450 BCE’, Internet History Sourcebooks Project, accessed 23 July 2022.

SOURCE 2

Diodorus Siculus, Books 34/35. 2. 1-13

- When Sicily, after the Carthaginian collapse, had enjoyed sixty years of good fortune in all respects, the Servile War broke out for the following reason. The Sicilians, having shot up in prosperity and acquired great wealth, began to purchase a vast number of slaves, to whose bodies, as they were brought in droves from the slave markets, they at once applied marks and brands.

- The young men they used as cowherds, the others in such ways as they happened to be useful. But they treated them with a heavy hand in their service, and granted them the most meagre care, the bare minimum for food and clothing. As a result most of them made their livelihood by brigandage, and there was bloodshed everywhere, since the brigands were like scattered bands of soldiers.

- The governors (praetores) attempted to repress them, but since they did not dare to punish them because of the power and prestige of the gentry who owned the brigands, they were forced to connive at the pillaging of the province. For most of the landowners were Roman knights (equites), and since it was the knights who acted as judges when charges arising from provincial affairs were brought against the governors, the magistrates stood in awe of them.

- The slaves, distressed by their hardships, and frequently outraged and beaten beyond all reason, could not endure their treatment. Getting together as opportunity offered, they discussed the possibility of revolt, until at last they put their plans into action.

- There was a certain Syrian slave, belonging to Antigenes of Enna; he was an Apamean by birth and had an aptitude for magic and the working of wonders. He claimed to foretell the future, by divine command, through dreams, and because of his talent along these lines deceived many. Going on from there he not only gave oracles by means of dreams, but even made a pretence of having waking visions of the gods and of hearing the future from their own lips.

- But, as it happened, his charlatanism did in fact result in kingship, and for the favours received in jest at the banquets he made a return of thanks in good earnest. The beginning of the whole revolt took place as follows.

- There was a certain Damophilus of Enna, a man of great wealth but insolent of manner; he had abused his slaves to excess, and his wife Megallis vied even with her husband in punishing the slaves and in her general inhumanity towards them. The slaves, reduced by this degrading treatment to the level of brutes, conspired to revolt and to murder their masters. Going to Eunus they asked him whether their resolve had the favour of the gods. He, resorting to his usual mummery, promised them the favour of the gods, and soon persuaded them to act at once.

- Immediately, therefore, they brought together four hundred of their fellow slaves and, having armed themselves in such ways as opportunity permitted, they fell upon the city of Enna, with Eunus at their head and working his miracle of the flames of fire for their benefit. When they found their way into the houses they shed much blood, sparing not even suckling babes.

- They tore them from the breast and dashed them to the ground, while as for the women — and under their husbands’ very eyes — but words cannot tell the extent of their outrages and acts of lewdness! By now a great multitude of slaves from the city had joined them, who, after first demonstrating against their own masters their utter ruthlessness, then turned to the slaughter of others.

- When Eunus and his men learned that Damophilus and his wife were in the garden that lay near the city, they sent some of their band and dragged them off, both the man and his wife, fettered and with hands bound behind their backs, subjecting them to many outrages along the way. Only in the case of the couple’s daughter were the slaves seen to show consideration throughout, and this was because of her kindly nature, in that to the extent of her power she was always compassionate and ready to succour the slaves. Thereby it was demonstrated that the others were treated as they were, not because of some “natural savagery of slaves,” but rather in revenge for wrongs previously received.

Reference

Halsall P (1996) ‘Ancient History Sourcebook: Sources for the Three Slave Revolts’, Internet History Sourcebooks Project, accessed 23 July 2022.

Source 3

How to Manage Farm Slaves

[Davis Introduction]:

Cato the Elder passed as the incarnation of all worldly wisdom among Romans of the second century B.C. The precepts here given were undoubtedly put into effect on his own farms. During the early Republic, when the estates were small, there seems to have been a fair amount of kindly treatment awarded the slaves; as the farms grew larger the whole policy of the masters, by becoming more impersonal, became more brutal. Cato does not advocate deliberate cruelty—he would simply treat the slaves according to cold regulations, like so many expensive cattle.

Excerpt from Cato the Elder, Agriculture, chapters 56-59

Country slaves ought to receive in the winter, when they are at work, four modii [Davis: One modius equals about a quarter bushel] of grain; and four modii and a half during the summer. The superintendent, the housekeeper, the watchman, and the shepherd get three modii; slaves in chains four pounds of bread in winter and five pounds from the time when the work of training the vines ought to begin until the figs have ripened.

Wine for the slaves. After the vintage let them drink from the sour wine for three months. The fourth month let them have a hemina [Davis: about half a pint] per day or two congii and a half [Davis: over seven quarts] per month. During the fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth months let them have a sextarius [Davis: about a pint] per day or five congii per month. Finally, in the ninth, tenth, and the eleventh months, let them have three hemina [Davis: three-fourths of a quart] per day, or an amphora [Davis: about six gallons] per month. On the Saturnalia and on Compitalia each man should have a congius [Davis: something under three quarts].

To feed the slaves. Let the olives that drop of themselves be kept so far as possible. Keep too those harvested olives that do not yield much oil, and husband them, for they last a long time. When the olives have been consumed, give out the brine and vinegar. You should distribute to everyone a sextarius of oil per month. A modius of salt apiece is enough for a year.

As for clothes, give out a tunic of three feet and a half, and a cloak once in two years. When you give a tunic or cloak take back the old ones, to make cassocks out of. Once in two years, good shoes should be given.

Winter wine for the slaves. Put in a wooden cask ten parts of must (non-fermented wine) and two parts of very pungent vinegar, and add two parts of boiled wine and fifty of sweet water. With a paddle mix all these thrice per day for five days in succession. Add one forty-eighth of seawater drawn some time earlier. Place the lid on the cask and let it ferment for ten days. This wine will last until the solstice. If any remains after that time, it will make very sharp excellent vinegar.

Reference

From: Davis WS (ed) (1912-13) Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources, 2 Vols., Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 90-97, Allyn and Bacon, Boston.

Scanned by: Arkenberg JS, Department of History, California State Fullerton. Prof. Arkenberg has modernized the text.

Collection: Halsall P (1996) ‘Ancient History Sourcebook: Slavery In the Roman Republic’, Internet History Sourcebooks Project, accessed 23 July 2022.

Source 4

The Conduct and Treatment of Slaves

[Davis Introduction]:

A Roman playwright, Plautus, writing about the time of the end of the Second Punic War (201 B.C.), gives this picture of an inconsiderate master, and the kind of treatment his slaves were likely to get. Very probably conditions grew worse rather than better for the average slave household, for at least two centuries. As the Romans grew in wealth and the show of culture they did not grow in humanity.

Plautus, Pseudolus, Act. I, Sc. 2.

[Ballio, a captious slave owner, is giving orders to his servants.]

Ballio: Get out, come, out with you, you rascals; kept at a loss, and bought at a loss. Not one of you dreams minding your business, or being a bit of use to me, unless I carry on thus! [He strikes his whip around on all of them.] Never did I see men more like asses than you! Why, your ribs are hardened with the stripes. If one flogs you, he hurts himself the most: [Aside.] Regular whipping posts are they all, and all they do is to pilfer, purloin, prig, plunder, drink, eat, and abscond! Oh! they look decent enough; but they’re cheats in their conduct.

[Addressing the slaves again.] Now, unless you’re all attention, unless you get that sloth and drowsiness out of your breasts and eyes, I’ll have your sides so thoroughly marked with thongs that you’ll outvie those Campanian coverlets in color, or a regular Alexandrian tapestry, purple-broidered all over with beasts. Yesterday I gave each of you his special job, but you’re so worthless, neglectful, stubborn, that I must remind you with a good basting. So you think, I guess, you’ll get the better of this whip and of me—by your stout hides! Zounds! But your hides won’t prove harder than my good cowhide. [He flourishes it.] Look at this, please! Give heed to this! [He flogs one slave] Well ? Does it hurt ? . . . Now stand all of you here, you race born to be thrashed! Turn your ears this way! Give heed to what I say. You, fellow! that’s got the pitcher, fetch the water. Take care the kettle’s full instanter. You who’s got the ax, look after chopping the wood.

Slave: But this ax’s edge is blunted.

Ballio: Well; be it so! And so are you blunted with stripes, but is that any reason why you shouldn’t work for me? I order that you clean up the house. You know your business; hurry indoors. [Exit first slave]. Now you [to another slave] smooth the couches. Clean the plate and put in proper order. Take care that when I’m back from the Forum I find things done—all swept, sprinkled, scoured, smoothed, cleaned and set in order. Today’s my birthday. You should all set to and celebrate it. Take care—do you hear—to lay the salted bacon, the brawn, the collared neck, and the udder in water. I want to entertain some fine gentlemen in real style, to give the idea that I’m rich. Get indoors, and get these things ready, so there’s no delay when the cook comes. I’m going to market to buy what fish is to be had. Boy, you go ahead [to a special valet], I’ve got to take care that no one cuts off my purse.

Reference

From: Davis WS (ed) (1912-13) Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources, 2 Vols., Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 90-97, Allyn and Bacon, Boston.

Scanned by: Arkenberg JS, Department of History, California State Fullerton. Prof. Arkenberg has modernized the text.

Collection: Halsall P (1996) ‘Ancient History Sourcebook: Slavery In the Roman Republic’, Internet History Sourcebooks

Task 3:

Using your ideas from Task 2, write a short response (one paragraph) evaluating the reliability and usefulness of your primary source.

References

Department of Education and Training (DET) (2022) Reading, interpreting and analysing History sources, Literacy Teaching Toolkit, accessed 4 August 2022.

Facing History and Ourselves (n.d) Big Paper: Remote Learning, Resource Library: Teaching Strategies, Facing History and Ourselves, accessed 26 July 2022.

History Skills (n.d.) How to analyse historical sources, History Skills, accessed 25 July 2022.

QCAA (Queensland Curriculum and Assessment Authority) (2018) Ancient History 2019 v1.2: General Senior Syllabus, Queensland Government, QCAA.

8. Historical Argument Jigsaw (part 2): How were slaves treated in Ancient Rome?

Anna Griffiths

Jigsaw by Clker-Free-Vector-Images, Pixabay License

| Curriculum context | Unit 1: Investigating the Ancient World (QCAA, 2018) |

| Historical thinking concept/s | Source analysis |

| Historical context | Roman society (753–133 BCE) |

| Learning intentions | Share analysis and evaluation of primary source from activity.

Synthesise information from all four primary sources. Write a short response to communicate a historical argument supported by evidence. |

Activity

- Gather your primary source and responses from the previous activity: How cause and consequence shaped Middle Kingdom Egypt and the Second Intermediate Period.

- Form groups of four. Each student must have analysed and evaluated a different primary source in Activity 1.

- In your groups, take turns to explain your analysis of your source. Take notes during other students’ presentations so you can discuss the analysis and evaluation of all four sources.

- As a group, synthesise the source information. You will need to consider:

- How the sources corroborate and/or contradict each other? Why might the sources corroborate and/or contradict each other?

- What representation of slavery in Ancient Rome is being presented? Is this representation through explicit or implied information? How do the sources’ motives and intended audiences influence this representation?

- What information or perspectives are missing from this representation

- Using three of the primary sources and your prior knowledge, develop a historical argument in a response to the question: How were slaves treated in Ancient Rome?

References

QCAA (Queensland Curriculum and Assessment Authority) (2018) Ancient History 2019 v1.2: General Senior Syllabus, Queensland Government, QCAA.