6 Water Transport

David Payne

For First Nations in Australia, water was used for transport as a quick and convenient way to traverse various area of water and country up rivers, or cross to islands for their rich food supply, or just to go fishing. These watercraft were designed to suit the local resources and the challenges to water travel within their environment.

The existing distribution of watercraft around Australia is rich and extensive. In contemporary times the watercraft were gradually recorded in colonial journals and logs, then later in research papers. Throughout their existence, the craft have also been kept as knowledge by the communities building them, and many communities still hold that knowledge and can continue the practice. Despite the extensive distribution and examples of the ongoing tradition, today there are still many people who are unaware that any Indigenous watercraft even existed.

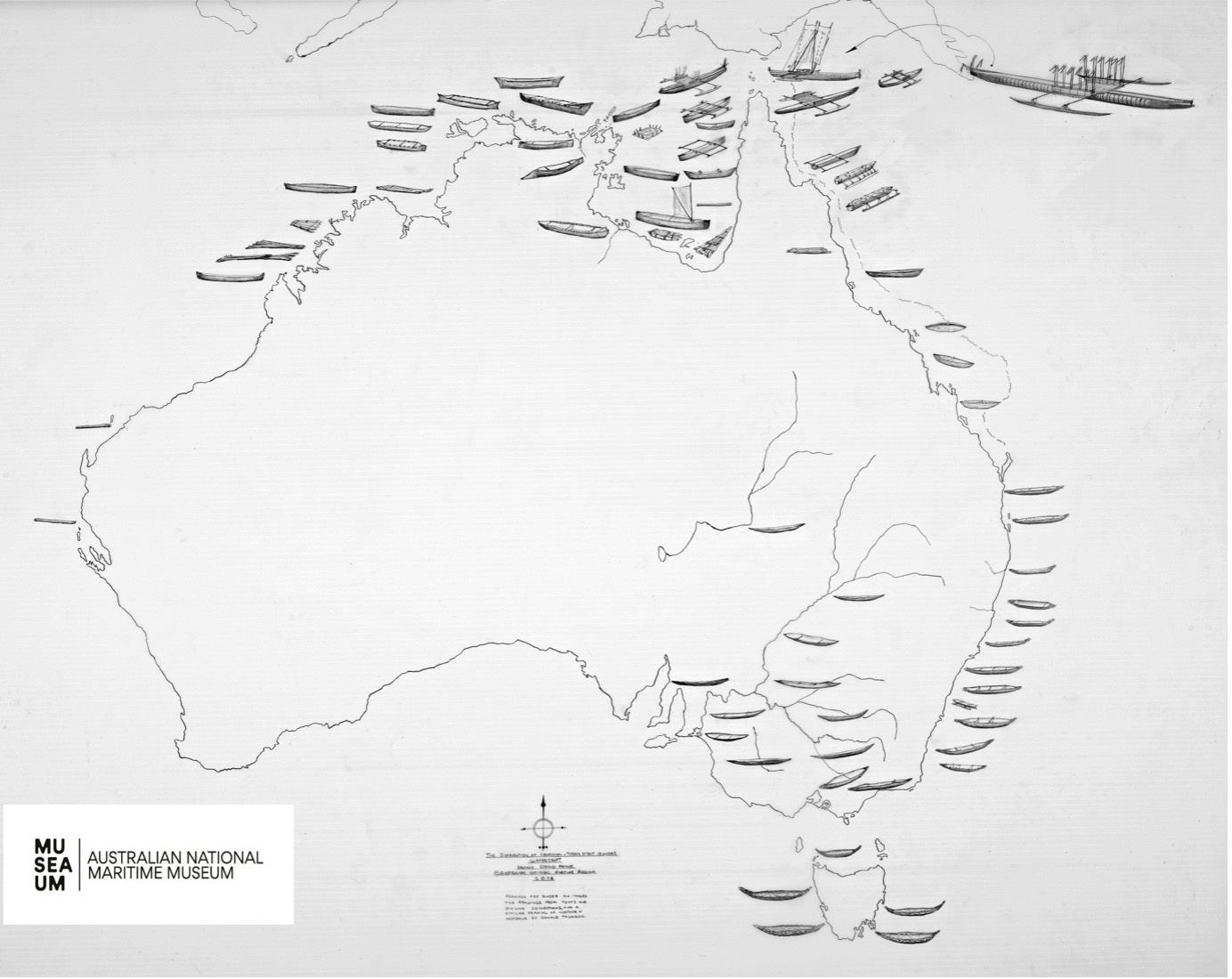

The map (figure 1) I have drawn records as best I can all those craft that existed at the time Europeans arrived, and almost all are still able to be made by their community.

The craft have been studied a number of times with basic maps that show some of the types and locations. Only one, by Rupert Gerritsen [1] was comprehensive, but he adopted symbols for each broad type. By drawing them individually, based on documented images and descriptions, it is possible to go deeper into these broad types and reveal the individual variation that exists, even within distinct types. Freshwater and Saltwater are a good division to start from.

Freshwater communities:

The freshwater, south east inland river system we know as the Murray Darling is the primary mainland freshwater region that supported communities with watercraft. Evidence from elders also connects similar craft to adjacent rivers flowing toward Lake Eyre in central Australia. This extensive waterway system is home to a distinct type, a single sheet of smooth bark formed into an elegant boat shape. It goes by various names but is known as a yuki by the Ngarrindjeri people on the lower reaches. Whilst it is commonly known that the prolific river red gum was used for their construction, it is less well known that one or two other barks were also available and used.

Elsewhere, amongst the numerous inland freshwater rivers, lakes, swamps and billabongs that exist across the country, the ability to make a simple raft for temporary use was also practiced in a number of places. Sometimes these were made on a more or less regular basis, other times it may have been an almost spontaneous construction to suit the moment and perhaps only used once or twice.

Saltwater communities:

The great majority of watercraft belong to coastal and estuarine saltwater communities. As can be seen on the map, their distribution covers over 2/3rds of the coastline, and includes the lower tidal and brackish reaches of the many rivers that flow to the coast. Bark canoes are the most numerous types, along with dugouts, outrigger canoes and rafts. Dugouts were a greater commitment of resources and more designed for deep sea travel.

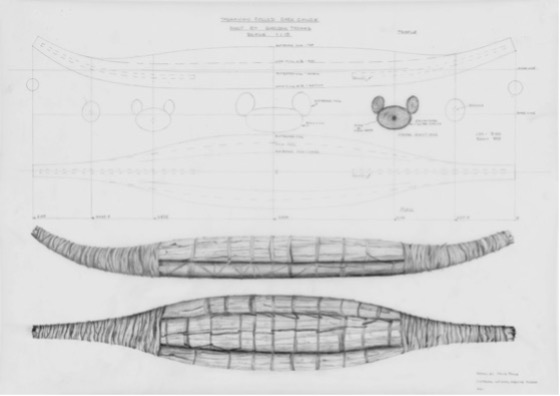

Tasmania is home to a very distinct type of bark canoe, the rolled bark canoes called ningher. Their relatively solid, three-part or multi-part configuration is quite different from other bark canoes on the mainland. Research is showing how different material choices, locations and uses gave subtle variation to the form within the overall concept of a bundles of buoyant material strapped together, then finished with a layer of stiffer bark.

On the mainland along the eastern coastline of NSW and Victoria the tied-bark canoes offer a good example of individual variation within a shared concept. They range from the Boonwurung and Kurnai communities in SE Victoria up along the coast as far as the Gubbi Gubbi community and the Fraser Island area in Queensland.

All these craft have the ends folded and tied together after the ends of the sheet have been thinned down, and the bark is heated by fire to help make it more supple. They are often both tied and fastened with a peg through the folds, and have minimal framing inside the hull. There are variations in the proportions, details of the ties and the method of framing. On parts of the NSW north coast the folds appear quite small and the bound ends are also turned upwards with a crease across the hull. From about Lake Macquarie south, the crease disappears and the folds become a bit wider. Ring frames with ties across the top pulling the frame and sides inwards appear in these craft, alongside the beam and tie system that is simpler to make. Gippsland craft show evidence of being quite long, and having their ends very tightly tied.

In most communities the bark sheet cut from the tree is then inverted to form the craft, and thus the smooth inside surface of the bark becomes the outside surface of the canoe. This also holds the resin rich, waterproof and strongest fibres, and as these are undisturbed by the thinning process, they maintain their integrity as a foundation for a strong canoe.

Along the north-eastern Coral Sea and Great Barrier Reef coast of Queensland the diversity of bark canoes begins with marked change from the tied bark canoes that have come up about as far as the Gubbi Gubbi community adjacent to Fraser Island. To the north including the area around the Percy Islands, a more complex three panel, framed bark canoe occurs over a small section of the coast. This craft has flat panels made from the ironbark, and has the top edge (or gunwale) as well as the joint ( or chine) at the bottom between the panels reinforced with a branch secured along its length .

Above this point on the coastline the beginnings of the sewn bark type appear. The principal element of these sewn craft is a neatly sewn join at the ends of the craft, bringing the sides together to form a rounded hull with a profiled bow and stern shape. Internal frames and longitudinal branches at the top edge help add support. The sewing is very precise and combined with a resin sealant provides a very watertight joint.

Torres Strait and nearby areas of Cape York’s coastline are home to outrigger canoes. The Torres Strait examples are perhaps the most elaborate Indigenous watercraft, and their construction is closely related to the Indigenous communities in nearby Papua New Guinea. Traditionally the main hull was made by a Fly River delta PNG community in exchange for shell and other trade items from the Torres Strait islanders seeking the new canoe. The final arrangement of outriggers, platform and sails were completed by the Torres Strait Islanders. Ian McNiven has made an extensive study of these craft and their social story, showing that their trading reach extended well south [2] and possibly east as far as Hawaii [3].

Different types of outriggers that show an influence from the PNG canoes are built by Aboriginal communities along the Cape York coastline. These show as simpler forms of single and double outrigger canoes, using dugout logs from the local region’s trees. They share the waterways with the sewn bark type, providing a distinct comparison of materials and technology.

The top end of Australia, from Cape York and Torres Strait across as far as the Kimberley and Broome regions takes this comparison of different types sharing the coastline and waterways even further. Sewn bark canoes in a variety of distinct profiles and framing techniques exist from the Tiwi Islands in the west across to Cape York in the east, but all sharing a sewn method of joining the sides to form the two ends, and even joining panels of bark together to form a longer canoe shaped hull. The evidence currently points to them pre-dating the introduction of the Macassan style dugouts seen throughout this region.

The dugout canoes were introduced by the visiting Macassin traders, possibly as early as the 1500s. Initially they traded their lipa lipa craft, but eventually the skills and tools to make them were acquired as well. On the whole they appear quite similar in construction and shape, another point of comparison with the sewn bark ones and their variation in style. On the western side of Cape York, they have adapted dugout canoe hulls with the addition of simple outriggers to form a more stable vessel suitable for deep sea travel.

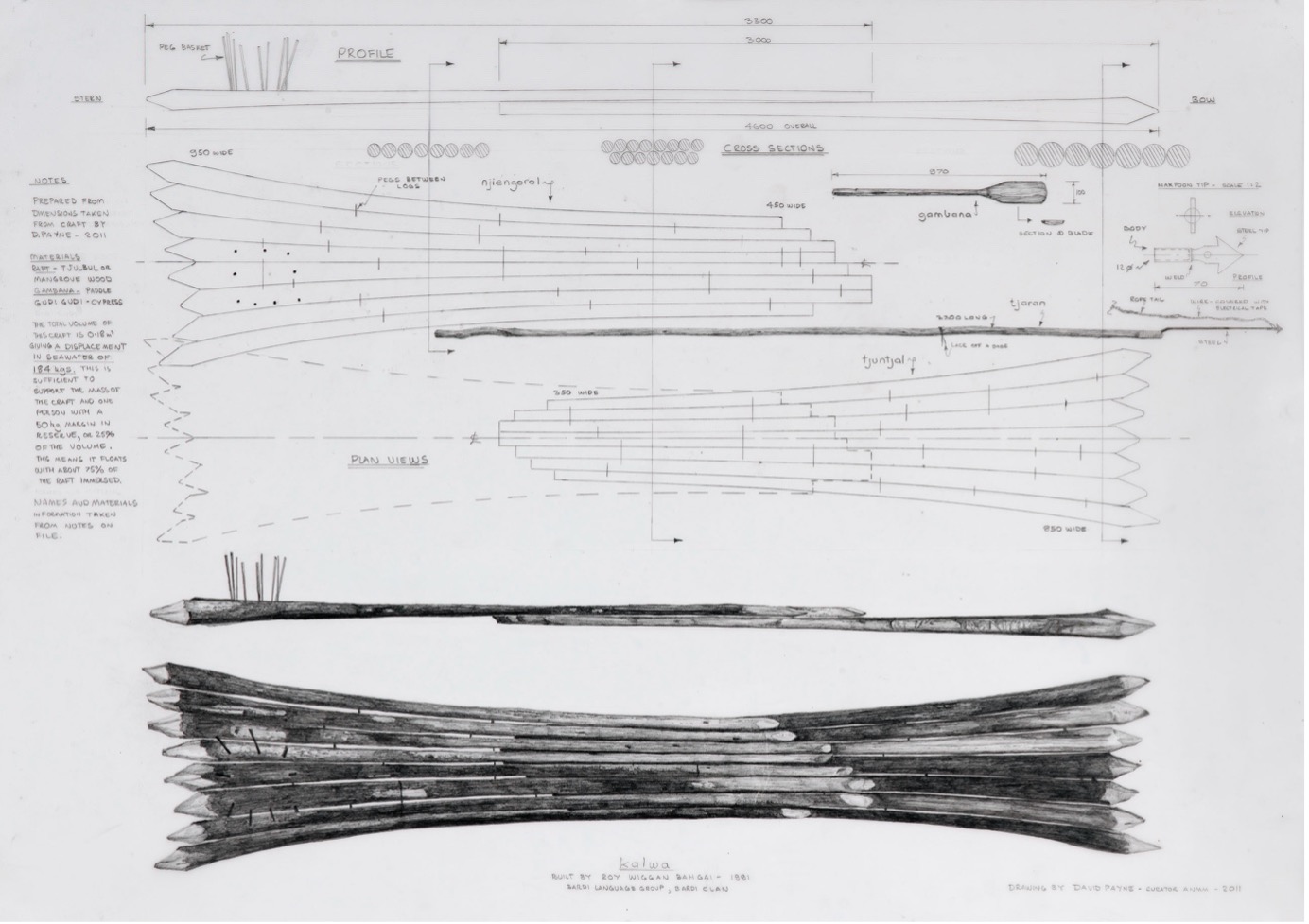

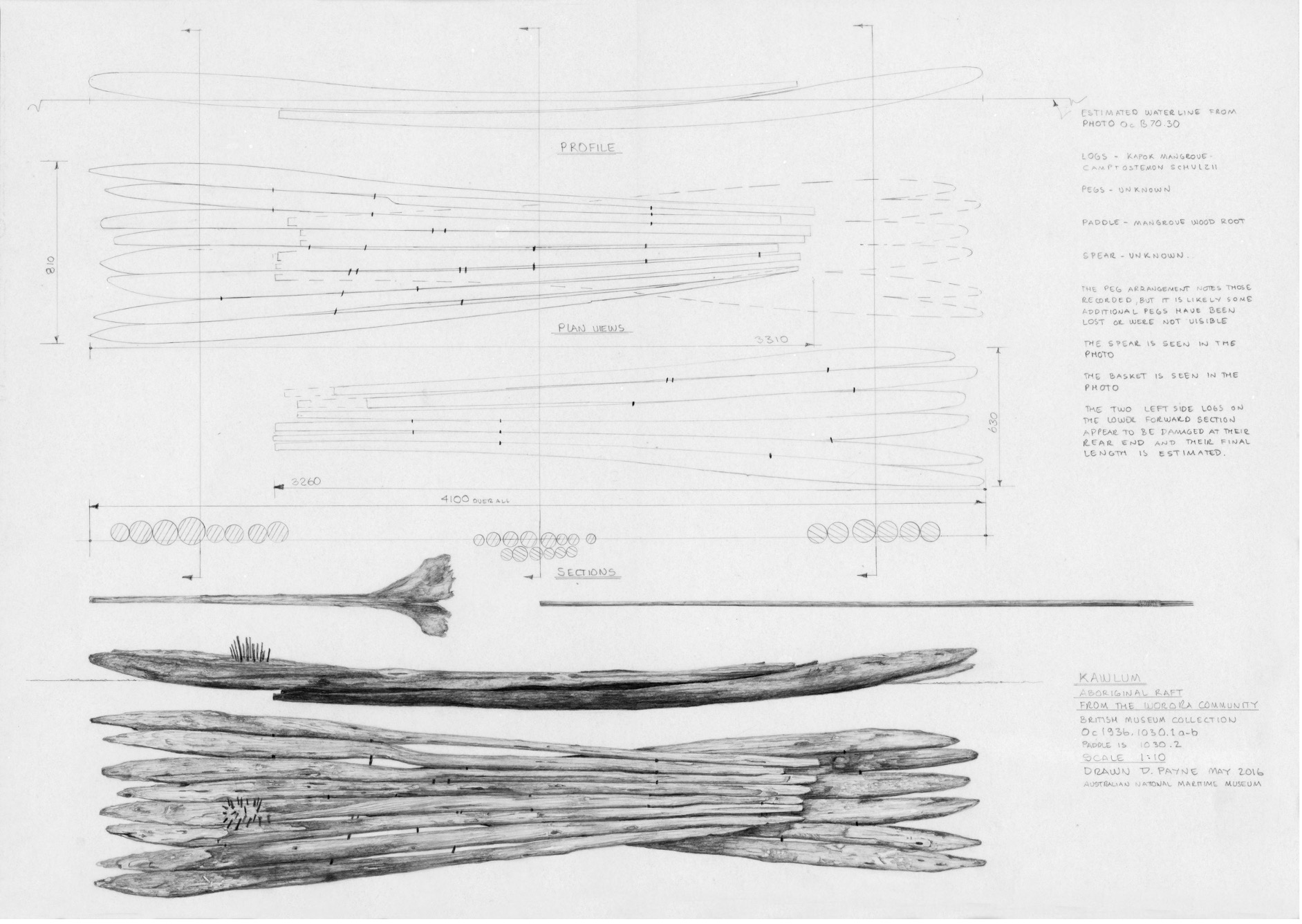

Added to all of this are the distinct raft types that would have co-existed in the same time frame as the many bark canoes. These are well known in the King Sound region of the Kimberley coast where kalwa or galwa double raft was used, with two fan shaped sections simply lapped together. Research is showing some variations of this type further to the west, including just single fan versions. Rafts are also represented by vee-shaped types, from the Mornington Island group in the lower Gulf of Carpentaria. the Kaiadilt and Lardil communities’ walba or walpa. Branches and trunks are bundled together and strongly tied to form a locked in rigid structure with sufficient buoyancy.

In addition to this, throughout Australia there seems to be consistent evidence of simple rafts and swimming logs being used in saltwater environments too. Sometimes they were made on a more or less regular basis, at other times it may have been an almost spontaneous construction to suit the moment and perhaps only used once or twice.

It seems that two thirds of the country have an array of specialised craft, but the south west quadrant remains empty of evidence. A lot of it is a rugged and dangerous coastline that would not be easy to use beyond the beaches, yet the existence of estuaries such as the Swan River where calm conditions prevail begs the question- were there craft that plied these waterways, but not recorded by early explorers? Community stories suggest that even in these estuarine areas there were no canoes as the water was shallow and everything that was needed could be sourced and managed in various ways without requiring a watercraft.

Overall, the map tells a story of the types, where they are related or where there are distinct changes, but in this form does not show how this might correlate to communities, and to the environment. It needs an overlay with both, to see how they could inform us further about the variations that exist. A study of stringybark for example shows it provides a good material over a range of similar trees from South Australia though to the top end, but how the pliability and other factors within the bark material compares to each other, and how this then relates to the eventual shapes and construction methods is worthy of further investigation.

This area is one where the results could help with a much bigger picture than shown on this map. If we compare the known evolution of the Australian environment since occupation with its current state, which has now existed in relative stability for about the last 7,000 years, then we may develop a new understanding of the possible chronology and age of these watercraft.

The construction of these water craft link to their diversity together, which we can highlight through a couple of craft.

The ningher rolled bark canoes (figure 2) from Tasmania seem to tell a story for floatation and stability, where the thin sheets of bark or strands of buoyant reed that are bundled together to form the craft, by bulking out the volume that gives the displacement needed to support its weight and anyone on board. The actual displacement volume is still porous and very dependent upon how tightly the reeds or bark is rolled together to minimise spaces that would fill with water as the craft entered the sea. Each craft would have varied, some better at floating than others, but their substantial size may be one element that reflects the difficulty in achieving volume.

A section through a rolled bark canoe shows the two outer hulls or sponsons around the main hull, creating on one hand a cockpit area protected from waves, but equally important, the volume out wide these hulls provide adds hugely to is stability. It is an idea seen again in a section through a modern polyethylene sit-on kayak where a lot of stability is provided by adding a section at water level on the outer side of the main hull, so that the craft are safe and usable by a wide range of people. At two ends of the time scale the same idea is being used.

However, an overall observation of the environment they are often used in and how well the shape is adapted to this is a consideration that I have made that deserves to be acknowledged. These craft when taken offshore of the coast are in a region where storms and strong winds can come up suddenly, and rough seas are very common. In these conditions an open canoe such as a tied bark canoe is vulnerable to being swamped on many occasions. However, the relatively solid shape of these rolled bark canoes probably allowed waves to roll over them, and they remain buoyant after the wave has passed and the water trapped between the side sponsons has drained off through the gap between them and the main hull. In this manner they are the ideal solution.

The Kimberley coastline is home to the kalwa, galwa (figure 3) and kawlum (figure 4)- a two-part, fan shaped multiple log raft and presents a good opportunity to highlight some vessel design issues, in particular that key element; you have to have enough volume for the craft to float. It’s easy enough to visualise a log floating roughly half in and half out of the water. The half that submerged is creating enough volume to support the weight of the log by itself, so the half that’s left above the water is free to allow the log to support some more weight before it too is submerged. If you put enough logs together, you have enough volume in reserve to support a person, or even a couple of people as evidenced in images of these being used. The key is recognising how much volume is needed.

Contemporary designers can calculate this, as I have done on the drawings which show two craft. Both will support itself and at least one person with about at least 20% of their volume still above the water. The larger one has sufficient volume to take two people. However, an experienced builder, working with the knowledge handed onto him in a sequence going back countless generations, will know by observation of the length and size of the logs he has just how much it might be able to support.

The construction is well thought out, with the shaped mangrove tree logs pegged together to create a rigid fan of logs in the same plane. Its use as a two-part craft for hunting dugong or turtle is a highlight. The line from the harpoon spear tip used to spear the animal is tied off to the forward part of the raft which is then separated from the aft part, with the animal secured to it and left to tire itself out before the raft section and animal are retrieved. This can be seen as a clever piece of lateral thinking.

There was also a single fan raft recorded, the brief sketch showing how it was made rigid with beams lashed across the ends.

What also needs to be highlighted is similar to the ningher. These rafts are quite open, the water can flow through and over them and they remain buoyant. This is a big advantage in this region of strong tides, whirlpools and rips. Over a month-long voyage in a sizable yacht, I have sailed through and experienced them myself and it is easy to recognise again how a conventional open canoe type would founder in these conditions whereas a raft passes through the waves unharmed.

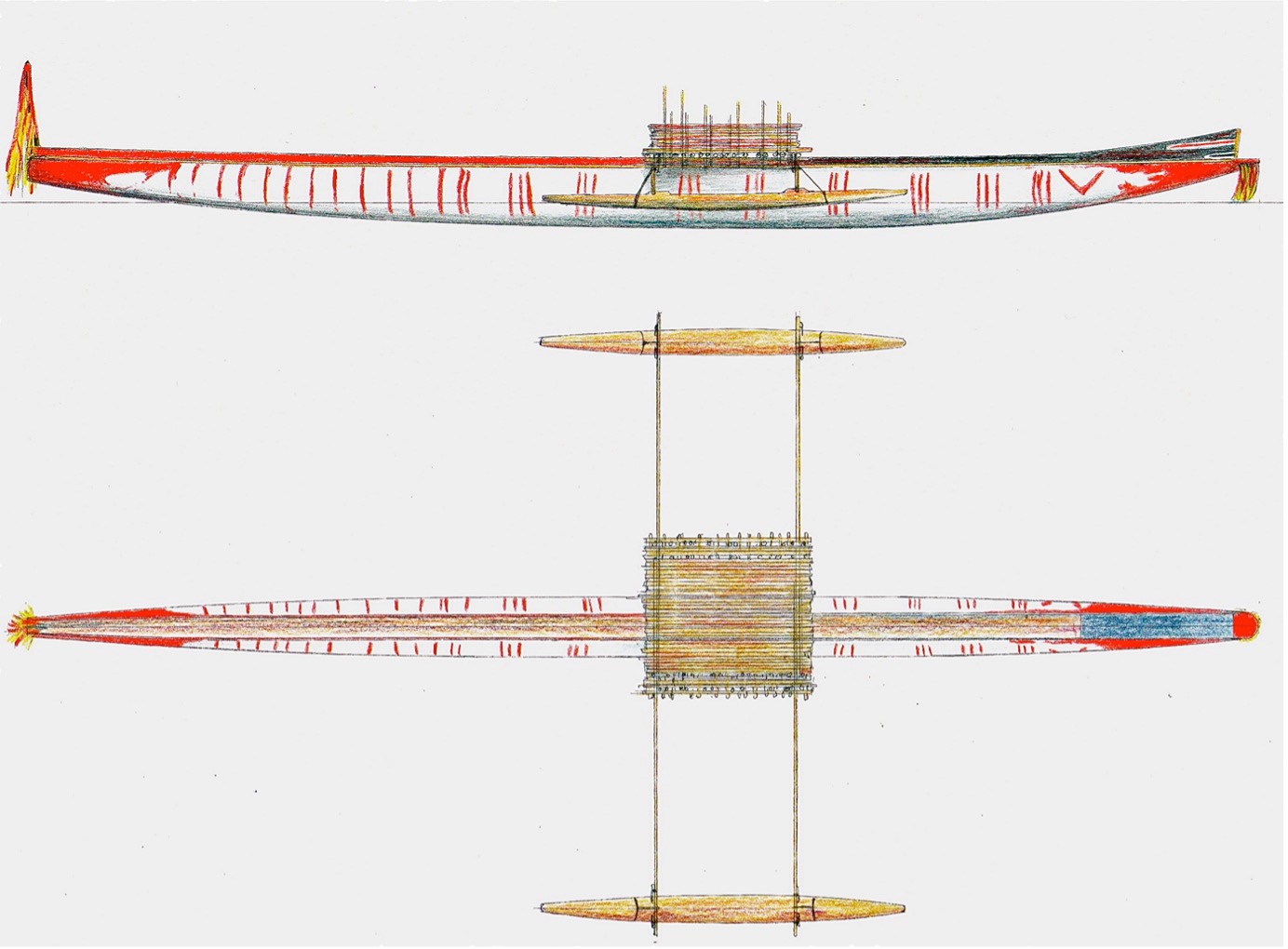

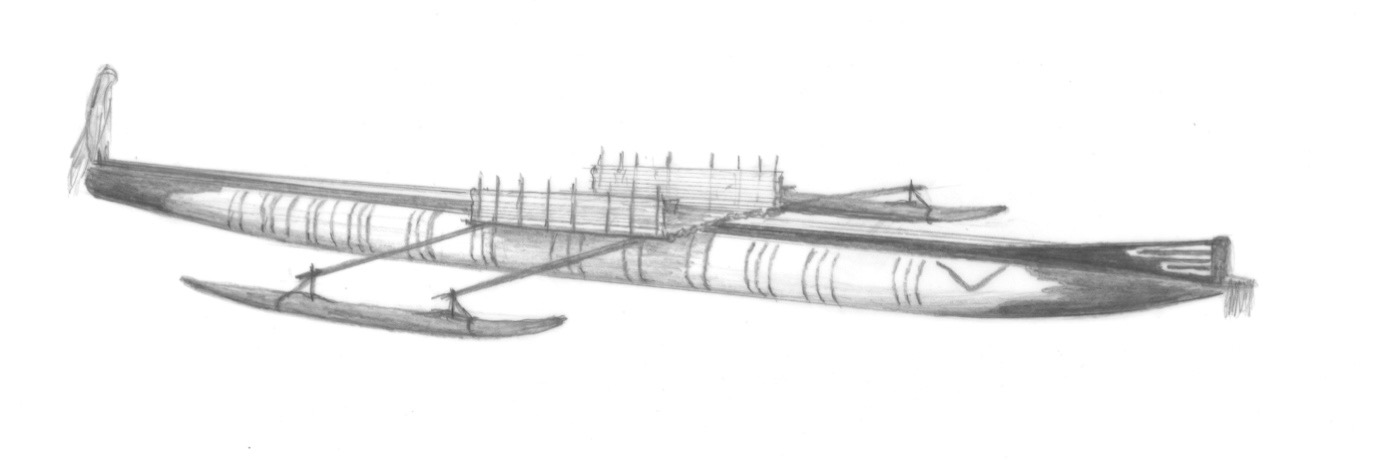

The double outrigger craft from Torres Strait Islander communities are the biggest and most sophisticated watercraft, the longest were up to 21m overall (figure 5). The main hull is made in the Fly River region of Papua New Guinea by their community, and this and other features share a strong connection to New Guinea community watercraft. The construction begins with a hull that has similar features to that used in the dugout canoe construction. The canoe hull is made from solid tree trunk that’s simply hollowed out, and has no frames. The hull has a strong base created by a heavy wall thickness on the bottom that compensates for the significant loss of strength created by the cut-out along the top quarter of the cross-section’s circumference. It also puts weight lower down as the sides have a significantly thinner wall thickness, helping lower the centre of gravity, very useful on this long and narrow rounded hull shape that offers little form stability derived from width, unlike the bark canoes.

Another feature not immediately obvious is that the craft is orientated to take advantage of the upwards taper in the trunk starting from its widest section at the base. Their custom is to always have the shape orientated so that the bottom of the tree becomes the bow end, and then the shape gradually tapers aft to become thinner, perhaps not by much in some trees. The overall distribution of the volume then places more of it at the front, and one factor for this is it provides support where a hunter stands ready to harpoon quarry. In this case the forward concentration of the hull’s volume distribution also requires the main structure across the hulls to be placed forward of the middle so that the hull will sit level in the water, and does not need an awkward distribution of the paddlers to compensate for the weight and bring it back to level trim. Outriggers such as Kia Marrina below show very elaborate construction and embellishment, and the width of the outriggers allows the floats to be smaller helping provide a balance between stability and manoeuvrability.

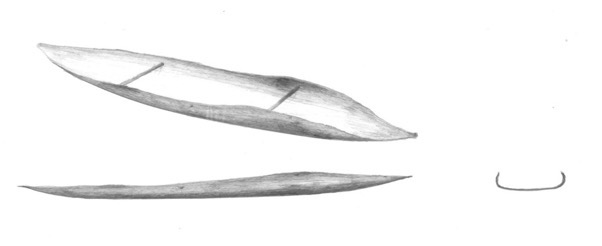

To finish its interesting to show how these watercraft craft have been developed to a high degree yet often appear quite simple, using the yuki (figure 6) from the Murray Darling River System. This shell-like craft can be classed in modern terms as a monocoque construction, whereby the panel is strong enough by itself to support the load with minimal or no support structure. The term comes from a combination of Greek and French, coined when the French created monocoque panels for aircraft in the early 1900s, and it was considered a very advanced method of building at the time. Essentially it is a shell or ‘stressed skin’ form of construction, where the shell supports the loads. Characteristically there are large panel areas spanning between the bare minimum of frames and longitudinal supports, perhaps none in some designs. Monocoque construction has had a resurgence of use with composite fibre reinforcement panels, and in the maritime field it is now well known for its use on dinghies, yachts, powercraft and other vessels.

Clearly the monocoque concept has always been well understood by Indigenous Australians. Bark is essentially a fibrous material. In some of the trees much of the fibre orientation runs parallel to the vertical trunk, ie: running up and down the tree or along the panel when it is cut. The interwoven nature gives a good cross connection, and often allows it to bend easily athwartships, while remaining stiffer and more rigid fore and aft. A yuki is generally made from red gum Eucalyptus camaldulensis and can be a shell that is 25mm thick. Their layers of fibres run more diagonally and interweave in different directions under each other forming a more homogonous panel that can be manipulated in both directions. The bend around the hull is easier than the bend fore and aft, but the ends can be moulded to rise up a little. The best yuki come from trees with a slight bend already in the trunk, along the length of the panel to be cut. Taking the bark from around this bend gives a nice curve fore and aft already built in that can be accentuated more easily at the ends, with heat and pressure. Once completed the canoes often have just two beams holding the sides apart.

Some may look more elegant than others when placed side by side, but that’s not the measure, the yardstick is how well each one relates to their circumstances- the environment they operate in and the materials it offers for community to work with.

Within individual types there is often subtle variation in the detail over the geographical range of the type. However, looking for a pattern of exchange and sharing of methods between the different types along the coastline doesn’t seem to show any gradual change and evolution between type or community. In fact, there are some quite marked changes at times. While gradual change might seem an obvious avenue to explore, its actually the wrong pattern.

What is probably shared but evolves and changes to suit each community is the broad concept or pattern of making and using a watercraft, the one first outlined when we built the nawi. Is the vessel needed, what are the resources, there is proper ceremony or protocols to observe, a method to be practised each time, a way of looking after it for use. Overall it is a series of steps that delivers the required craft, steps that are repeated each time to maintain continuity, stability and sustainability.

References:

1. Gerritsen, Rupert. (2008). Australia and the Origins of Agriculture. BAR International series 1874. Oxford.

2. McNiven, I.J. (2011). ‘Canoes of Mabuyag and Torres Strait’. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series. Queensland Museum.

3. Briggs, Victor (2023). Seafaring: Canoeing Ancient Soonglines, Magabala Books