11 Materials and Construction

David Payne

Introduction

The Aboriginal people with their culture and community have been in Australia ‘for ever’. Contemporary western science and archaeology tell us people crossed over to Sahul ( a paleocontinent that included Australia and Meganesia by watercraft, somewhere between 45,000 to 60,000 years ago (Wikipedia, n.d.).

Creation stories refer to the spiritual origins of Aboriginal people on this country, with no measurable time span as to when that was, and these stories are still true today. The spirit of that creation remains in the land around us.

Watercraft feature in Dreamtime stories and watercraft exist today, therefore they have been part of the countless generations that have existed before the present. This legacy leads us to the understanding that in some form or other, these watercraft have also been here ‘for ever’.

What they look like now may or may not be what they looked like then, and this should not matter in the bigger picture. Speculating what they once were and then how the first craft might compare to the contemporary craft can easily head off on a subjective path of discussion and theory. What is important is the process that delivers these watercraft, and there is reason to accept that this process has, in concept, been developed and remained consistent for much of, and perhaps almost all of this ‘for ever’ timespan.

The example I will employ later in the chapter outlines a process that is used for one watercraft that is very familiar to me, the nawi tied bark canoe. I build them and pass on the instruction as my responsibility within my Yuin community circle. The process is a cycle that is repeated every time one is made, with a combination of spiritual or deep knowledge and practical aspects ensuring continuity in the community and sustainability within the environment. It also happens to be a good design.

This process is about taking only what is needed and doing ceremony for respect to elders, to mother earth, asking the trees for their permission, to settle ourselves, then for healing afterwards. Each time we move on to another place out of respect for the resources, to not take too much from one place.

There is cooperation with each other as the nawi is formed, respect for what the material can do and cannot do, then there is care when it is in use to maintain the craft for a length of time before it is returned to mother earth. It is not there to be used for just a few times, or for one season or cycle. In current marketing terms, this is not a single use, throw away item.

BUILDING CANOES

Vessel design as a profession is now taught as a branch of engineering called naval architecture but there are many who say it is an art as well, particularly with yacht design. Art has that intangible feel to it.

Form can follow on from function, but this often lacks a sympathetic, aesthetic style. We as people also see something within shapes that stirs our emotions in relation to beauty or elegance, and that also defines the chosen form. It can become a guide for judging if your object is going to work as intended. With boats, the flowing lines and form that are generated in the structure can be that guide, when they are looking right, they are in sympathy with the action and flow of the water and waves which it must move through.

Design by accident is often an accident waiting to happen. So, it might help to begin with an outline of what are the practical needs to be considered to make a floating craft, what requirements there are within the engineering or physics that must be observed to avoid accidents.

Vessels are a significant structure and like any structure they need to respect essential engineering practicalities to hold together. In addition, there are specific vessel design factors in relation to their volume and shape that will ensure they float and make progress on the water with the load they are expected to carry. Formal education now gives these factors names and methods of calculation, but there is much that can be observed from nature that would help make the process just as reasoned. Trial and error can help you arrive at a working solution, but clarity within this observation will reduce the errors considerably.

A boat is a complex item, but five things as broad concepts seem to stand out.

It has to be shaped to have:

- Enough volume to support the weight of the vessel and its load

- Enough freeboard in reserve to allow for waves, pitching and rolling.

- Enough stability so it does not capsize easily

- A shape to go through waves and water easily without excessive drag

- A shape that is controllable and can be propelled in any direction as desired.

Then there is construction, and the shape has to be built strong enough to:

- float in the water and support those in it

- accommodate changes in loading over the hull due to wave motions and being propelled

- be handled out of the water and stored on shore

If there is one thing that stands out as a priority it is this- there has to be enough volume to support the weight of the craft and what it will carry, with a reserve capacity. The remainder is fine tuning the shape of that volume and the hull overall to work better, and having it strong enough for its task and environment.

Instead of talking about weight, modern vessel designers talk about displacement, meaning how much water is displaced or pushed aside when a vessel floats. Think of it as the hole or shape created in the water by the floating object. If it were a ball, it could be a half sphere. With a boat, the displacement shape is the submerged part of the boat below the waterline. That volume is the first part of an important consideration, and when weighed that volume of water pushed aside or displaced will be equal to the weight of the object that created the hole- that is the basis of the Archimedes principle.

Therefore, a canoe or raft has to have enough volume to support its own weight and the added weight of the people and whatever else it carries. It then requires a margin, in the form of additional volume and depth to the hull, obtained by adding height to its sides above its waterline called freeboard, to stop waves coming in and allow for rocking from side to side. To restate things, this additional material becomes a margin of safety providing additional volume in reserve.

And the bottom line here? This can be observed by seeing something floating, adding a weight to it and seeing how much lower it floats in the water, and deducing what the limits are before it submerges, or alternately what extra is needed to allow for more weight. You learn to see and feel the size of the hole in the water you need to fill and then deduce the volume needed for your canoe. You know how big to make it.

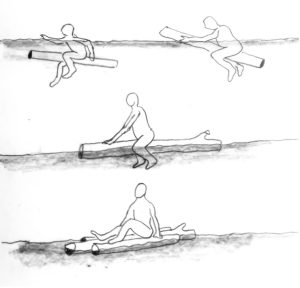

A swimming log will serve to illustrate this. If the log is too small it will all be submerged and not provide any assistance to the swimmer. But if it is big enough some part will remain clear of the water and the swimmer will also be partly supported out of the water. If you keep looking you will eventually find a log you can sit on with just your legs in the water. Then put the three of them together and you have a basic watercraft with volume and stability.

From swimming log to raft. D. Payne, Australian National Maritime Museum.

All the Aboriginal watercraft in Australia recognise the many requirements beyond just the volume; they have the necessary engineering and hydrodynamics for their purpose within them, and it seems most likely this was all determined through observation and gradual improvement. It wasn’t a matter of discovering engineering as a principle of design then building a craft, the craft that were best and hence their design was repeated, were those that observed the necessary practical requirements to build a well-engineered watercraft, otherwise it would not work in the first place.

The plan

The plan and the information for building were not drawn or written down. The process from the natural material to the finished watercraft was handed down by the older people to the younger people. Initially it was observed, and you probably just grew up with it from the day you were first placed in a canoe and developed a feel for their motion in the water.

When the time came to participate it was spoken about, described, modelled or demonstrated, then finally acquired through repeated participation in the building process until this plan, including the things that could go wrong, had been absorbed. The plan was kept as knowledge within each community, and it was shared and passed on, ensuring continuity and community cohesion.

The craft kept to a ‘plan’ to recreate the canoe each time, it was a process that was practised and renewed through the continued seasonal construction of the craft. Generally speaking, there was apparently no desire to change or improve this model a community had arrived at, it fitted the equilibrium of living with the environment. Within the various communities it seems that maintaining a stable and sustainable culture was a much stronger practise than one seeking continued technological improvement.

However, the design changes depending on where and when you build the canoe (see Chapter 12), the environment supplies the resources and the challenges of water travel that determine the construction.

Exercises

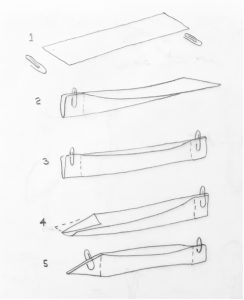

For now we can do a paper exercise that demonstrates some basic aspects of simplicity in this process very quickly.

- Take a sheet of paper, cut so its length is at least four times its width. Note how it bends easily in either direction.

- Bring one set of corners on a short side together and secure with a paper clip, then do the same with the other. Now the shape holds itself up.

- Take off the paperclip from one end, fold the corners inwards, then fold it up again and secure with the paper clip.

- You now have a pointy end.

You have also just made a Yolgnu nardan or derrka canoe shape, the type seen in the movie Ten Canoes.

Drawing by D Payne

We have demonstrated some key points to take in.

- We’ve taken an available resource and not processed the material

- In simple steps we have shaped it

- We were letting it form in a way the material is happy to move

- We have an elegant and usable object

Think what it would mean if all engineering could be this simple and effective?

Building a canoe

Why are we building a canoe, or building yet another canoe? Why are we doing this today? This should be a question to ask before you start using resources.

The purpose of a canoe or other form of watercraft is to harness the waterways for transport. It enables easier movement within or between communities, improving communication, supporting social activities, along with fishing and food gathering. We can walk on the land, but the canoe becomes an object to take advantage of the water that is already there, and often provides or more direct link on the journey being undertaken.

With that reason we will create a nawi tied bark canoe from the eastern coastline. I have been building tied bark nawi canoes for over 12 years with the Yuin community. Within this a special relationship has been made my mentors, Saltwater elders Uncle Dean Kelly (Yuin) and Uncle John Kelly (Dunghatti). For all of us, it has been a period of relearning the past practices. Because the detail comes when you are there, being an active participant in the story, I can share only a broad description. This follows the teaching methods of my elders, mentors and community,

When I began my journey over a decade ago it was with a model, then a 3 m long canoe full of leaks. It was just about the building back then; I didn’t realise many aspects which I have since learnt. The actual building of the canoe from the sheet of bark is just the middle stage in a passage that begins with sourcing the material and progresses through the construction to the eventual use, but they are all stages with an impact on the design and engineering, as well as a strong cultural or spiritual relationship. So, its not just a practical exercise of construction, it’s a wide-ranging process where each step is an important connection.

There is also another aspect not immediately obvious. Building nawi became an opportunity to bring people together for many other much more things. The men make much more than just the canoes. They make friendships, listen to the elders and teachers, and understand and practise the key behaviours of patience, observation, responsibility and respect. They talk, yarning openly about personal issues. As both uncles said to me recently in the wake of personal tragedy ‘This will be healing for you, brother’. It has helped me through a difficult period, and it’s brought a lot more to others inside our group. So, the building process has other qualities as well.

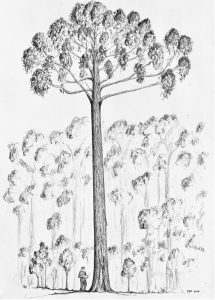

The tree we use is the stringybark, so having brought our group together, we begin with the tree.

We ask permission from the tree to take the bark. By this I mean we observe what the tree is telling us. Is it saying to us it is the right tree, the right size, are we in the right place, is it accessible for us to secure the bark, is this the right season, and taking it here will not deplete a resource dramatically. Respect starts here. Before we start, we let the ancestors know we are there and acknowledge the tree’s gift, and do this with a smoking ceremony. Then when we have taken the bark, we do another smoking ceremony to close off and offer healing to the tree.

With the sheet of bark secured we can now build a nawi. Here is the story of the nawi.

Grey, red, yellow.

Fire, forming, finishing.

These are the individual chapters in the story I tell for building a nawi. It is a story that has grown gradually until I have been happy with how it flows.

First, the colours – grey, red, yellow.-you often see them at sunrise. They are also the layers of bark we work though. The grey outside layer is taken off to reveal a stronger red bark. This red layer is trimmed down until the body of the nawi can be formed, then at the ends the red bark is removed to reveal the yellow layers, which have the strongest fibres. They are the inside face next to the hardwood trunk of the living tree, whose outer rings carry a flow upwards from the roots to the branches and leaves. But these yellow layers are also very much alive – they take the downward flow back to the base of the tree They are adding to the spirit and life that are always in the nawi, and this comes from Mother Earth and Grandfather Sun. At the ends, this yellow layer is thinned down further.

Fire is a tool to respect, and a friend to work with; use it to heat these thinner ends to help soften them further. Forming the nawi, you take the sheet off the fire, bring up the sides to make a body, and then fold the softened ends to create a raised bow and stern. Finishing requires you to peg and bind the folded ends, then hold the sides apart with branches that push out against the cross-ties that pull in.

Now it’s done. We have shared the knowledge and our nawi is complete. It’s hard, physical work. Our hands are dirty, but we have a feeling of great satisfaction. For everyone, the process of working the bark into a nawi has taken patience, observation and respect for the material, along with personal responsibility and respect for others to work as a team. The finished nawi has its own individual look, but in concept it is the same as all those that have come before it – a mark of respect for the elders and their knowledge which has been passed on, observed and now preserved in another generation.

Before we go further, how does this connect with those points made earlier about what a vessel needs to float? Our period of building these craft has shown us how to arrive at the answers by observation. However, we did start with a basic guide, as some of the early colonial reports describe basic elements of the process and even some basic dimensions. However, in the end we have had to relearn almost all of it, and arrive at our own conclusions about process, dimensions and scantlings, whilst delivering a craft that looks identical with the depictions of early artists.

The first three key points of volume, freeboard and stability came quickly, by building the canoes and observing them in the water noting just what they could support, and how they felt to paddle. We soon knew how wide and long a craft needed to be for one or for two people. Inverting the bark to give a smooth outer surface gave us a lower drag and retained strength, and the longer the craft the easier it was to paddle at a reasonable speed. Some of the craft came out quite flat at the ends, this taught us the need to have them fold so that the bow and stern rise up so it can go over waves. With these features in hand, we were meeting the last two objectives. Overall, we had a shape that satisfied what those engineers, the naval architects, call the hydrodynamic requirements – the how and why of a vessel’s ability to float and move in a usable manner.

Strength requirements also came for building many craft and learning from each one. We learnt how far to go with thinning down the layers simply by going too far in the early days. We learnt what proportions were best, and what thicknesses were best. There is a lot of feel in this, feeling the bark to see how pliable it is as it is being worked on, and understanding what feels right came with practise. With experience we found we had craft that were strong enough to support the load it carried in static and dynamic situations, and we learnt how to handle them out of the water so they were not damaged.

Then the last phase, the use, is something we are now learning more about. Many of the craft we built went on display, and in that controlled environment they held their shape as a result. Some deteriorated, but we didn’t really ask why, often putting it down to poor support. Others took to the water, sometimes for just one event, but a few did multiple events before being retired. They all leaked, and some had significant cracks sealed up as best possible, but they still had a very limited watertight margin for the time they could be used on the water before being sponged dry.

We began to solve these leaks by sourcing our bark in the right season so it was quite moist and came off the tree easily without developing cracks. However, even then if there was a delay in forming a nawi from the recently cut sheet it would dry out gradually and develop some cracks, so we still had faults to deal with. We experimented and learnt more about traditional resins that would help seal the remaining leaks, working principally with different combinations of grass tree resin, the red eucalyptus gum that seeps often prolifically from angophoras and iron barks, ochre, black wattle resin and water. Clay and paperbark were part of the mix too. And once again, collecting these had to be done with respect to culture and community, and always only taking what was needed at the time.

Something else is just becoming apparent as we build bigger and better nawi without any cracks in the bark to begin with. It is about learning how to maintain them for use on the water. The observations and actions we need to take are still being learnt, but it may come down to something simple as an answer, don’t let them dry out completely.

Reflection

Let’s go back to our paper model. How nice it would be if all engineering could be as simple and as sympathetic to the environment. There was a time and place when it was, and through tens of thousands of years of history that place is still here, and we are in it now.

What have we learnt overall? It is a practical and spiritual process; the latter keeps the former in balance. It is a journey that is an example where the actual building, the practical engineering part is significantly influenced by much earlier actions that should be observed, and they help ensure it’s a process that works in sympathy with the environment and the material rather than coercing both into unnatural behaviours.

Contemporary practice follows an industrial and commercial process that by and large supports the individuals taking part with everyone focused on their own part of building the object, while manipulating the materials along the way. Instead, we have walked through a cultural act that has brought community together to do more than build an artefact, and created this in sympathy with the environment. It is an example of where Indigenous engineering and construction satisfies needs, whereas modern engineering seems to becoming more about satisfying wants or luxuries, things that go beyond the basic need. And like Country, the canoe has combined not just the tangible but also the intangible elements throughout, they cannot be separated.

References

Payne, D. (2023). Canoes. Australian National Maritime Museum. https://www.sea.museum/2016/12/15/australias-first-watercraft/canoes

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Sahul. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sahul

Dreamtime stories of watercraft include:

- Canoe in Orion -Yolgnu;

- Illawara and 5 Islands -Yuin;

- Three Brothers – Bundjalung;

- Ngurunderi dreamtime canoe– Ngarrindjeri