14 Indigenous design: Water Country

Kate Harriden

This chapter introduces Indigenous design principles in the context of water and highlights their theoretical and practical applications. I write this chapter as yinaa wiradyuri/wiradyuri woman, water woman and engineering sceptic. This chapter includes some activities to encourage you to engage with these ideas beyond this book. An exercise to develop student’s sense of country and Indigenous design principles is also included.

All design systems operate with an associated scientific system. The scientific system you are familiar with came with the colonisers and is referred to as settler-state science in this chapter. Human centred, this science tends to be exploitative and extractive, and marked by its reliance on western engineering and its use to change waterscapes (harriden, 2023). Settler-state science results in a transactional understanding of scientific priorities, practices and outputs. This brief characterisation of settler-science informs its relationship to water, with water regarded as transactional; a commodity to be used for human purposes and profit. By contrast, Indigenous sciences are country-centred, relational and adaptive (harriden, 2023), requiring the human be but one of many entities considered when practicing science and crafting designs. The relationality in Indigenous sciences strongly contributes to water being seen as having life and rivers regarded as kin which is the basic premise of this chapter.

Indigenous design principles stand independent of settler-state principles and are best used as such, rather than attempt shoehorning them into settler-state design frameworks and paradigms. The principles presented in this chapter are high level and do not represent the specific design principles or knowledge of any particular Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander group. Indigenous design principles exemplify how all aspects of country are considered simultaneously, thus reflecting country’s indivisibility and the relational interconnectedness of Indigenous sciences with other types of knowledge.

Country

Country is an actor in Indigenous design, hence when using Indigenous design practice you are working with country. The importance of country cannot be overstated. Thus, it is necessary that when designing a technology or process that students have some understanding of country, its complexity and enduring significance to Indigenous peoples. Designing is working with country, including the materials used and the sites where they are accessed, the physical sites where designs are located or used, and sites where the manufacturing and construction occurs.

Country continues to guide Indigenous people practices and daily activities. Rather than empty rhetoric, the phrase ‘caring for country’ is a guiding ethos for Indigenous lives. County is more than soil, water, plants and animals; more than ‘the environment’. Certainly, these are part of country, but so too are the stars, sky, moon and sun, earth, wind, air, mountains and ancestors, songlines, dreaming, humans and language. How these, and other, entities relate to each other within in specific place/space is country. Importantly, country is indivisible (Marshall, 2017). This means no one entity can be considered in isolation or attributed more importance than another. That is, the web of relationships between all aspects of country is the primary focus of research and design.

As well as indivisible, country is unique. No one country is the same as another, be it the waterscapes, landscapes, skyscapes or the animals and plants. Thus, there is an element of bounded territorially to the web of relationships forming country. Certainly, the ancestors, dreaming and songlines of each Indigenous Nation differs. These differences contribute to an imperative of country centred design – to design with country.

Activity 1 Introduce yourself to water country

Spend some time every day for at least a week consciously, deliberately walking around a body of a water near you. If you can walk to this body of water, do so in a conscious and deliberate manner. Some tips:

- Go at different times;

- walk in different directions;

- look up as well as around; and

- be quiet.

Walking consciously and deliberately will help you start seeing some of the web of relationships that create country, including some of your relationships in that web. As you begin building your relationship with this body of water, you may find yourself greeting it upon arrival (country loves hearing our languages, so if you speak an Indigenous language, use it).

Indigenous design principles

When working with country and its people, the appropriate protocol is to work with the specific design principles and practices of that country and people. Thus, while the broad high-level principles presented here are good for country and inform all Indigenous design practices, the appropriateness of a specific design will vary from country to country. Recognizing that country is indivisible, the water examples in this chapter are designed to support your recognition of Indigenous design principles as applied around waterscapes, rather than suggest they only be used for waterscape design requirements.

Country centred

Being country centred reflects the indivisibility of country, with all decisions, including design, putting country first. No one aspect of country, whether water, an eastern water dragon or soil, is regarded as more important than another, or managed separately. The consequences to country, as a complete unit, are considered and weighted appropriately in decision making and action taking. One aspect of country can not be ‘sacrificed’ for another.

Most design projects crafted in the settler-state framework do not centre country. Indeed, they are often crafted in the face of country’s complexity, focusing on one aspect of country. Consider the following example. Figure 1 shows a reach along Yarralumla Creek on Ngunnawal country in Canberra before a government initiated ‘stream rehabilitation’ project. This site is downstream of the storm water system to which the stream has been converted.

Figure 1 shows a heavily vegetated bank and shallow pool of water, indicating this reach to be less heavily modified than upstream. Hidden by the vegetation at the top left of the image is a natural riffle located immediately downstream of where the stream has a second (terminal) channel. Also unseen is the large raft of eastern water dragons flourishing in this section of the stream and the diversity of macroinvertebrates in the water plants. Despite this complexity and generally low levels of turbidity, the stream rehabilitation project was designed to manage solely turbidity (ACT Government, n.d.). This project specifically and consciously divided country.

Figure 2 shows the same reach upon completion of the so-called stream rehabilitation project. By focussing only on reducing turbidity, it was considered appropriate to widen, straighten the channel and construct three large artificial riffles in the channel. This was clearly a human-centred design. Consequences included the extinction of the local water dragon population, the removal of banks and their associated vegetation. Outcomes such as these are not possible when centring country.

Designing with country places the emphasis on using extant features in country to achieve design outcomes, rather than removing country to achieve design outcomes. Designing with country includes using on-country features to layout camps, for example trees as camp windbreaks or tended and mended as shade or water trees (Page & Memmott, 2021). The use of lava flow formations for fish and eel traps at sites such as Budj Bim is another example of designing with country.

Settler-state approaches to design sometimes feel like ‘design despite country’. Stormwater systems are an example of this approach. Despite country providing floodplains and a range of physical processes to accommodate high flow events, some humans have felt it appropriate to modify streams to support the rapid removal of the increased runoff created from a particular form of urban development. Contemporary urban water practitioners are gradually coming to understand that the design values and practices reflected in storm water system design are damaging urban waterscapes and leading to increased flooding.

Everything is animate

Indigenous ways of being and valuing, including those of science and design, regard all entities in the web of relationships forming country as animate. This need to be remembered and respected. Songlines, art and dance tell of times when mountains, trees or birds, for example, manifest in human form. Their animacy remains constant across the physical forms taken whether human or a more-than-human entity of country. As will be outlined in the water specific design principles section, creeks, streams and rivers are animate and the water within them is regarded as having life.

The animacy recognized in non-human entities is an expression of the relationality that imbues Indigenous ways of being and valuing. Relationality is a central tenet of Indigenous worldviews, referring to the connection between all entities and reflecting the web of relationships that forms country. Relationality exists between ideas and entities, meaning that not only do Indigenous people see the world in terms of relationships but also “feel the world as kin” (Tynan, 2021:4). The belief that every thing is alive and related strengthens the country-centred imperative, fundamentally altering what can be regarded as legitimate design choices and processes.

Functional sophistication

A hallmark of Indigenous design is that an artefact may seem simple in both design and material, but is extraordinarily effective. For example, Page and Memmott (2022) highlight the woomera as an example of functional sophistication, as it can be used for hunting and carrying food gathered while hunting. The boomerang is a better-known example of the functional sophistication of Indigenous design.

The leaky weirs designed in my research were to modify baseflow in open storm water channels. The weirs were simply lengths of untreated pine cut to a template roughly reflecting stream bed shape and attached with coach bolts in the expansion joints. Yet the changes in channel reach conditions, in terms of biodiversity and a range of physical and chemical processes for example, were significant. Figure 3 shows the channel flow before the leaky weirs are install; Figure 4 is after weir installation.

Immediately obvious from these images is the impact on flow morphology, as the flow slows and widens to pass around the weir. While hard to observe in Figure 4, this simple intervention traps sediment, which influences bed morphology and the retention of organic matter (Fig 5), allowing insects to thrive to the point that a mother duck brought ducklings upstream to forage in the resultant islands and accumulated sediment.

Embedded storytelling

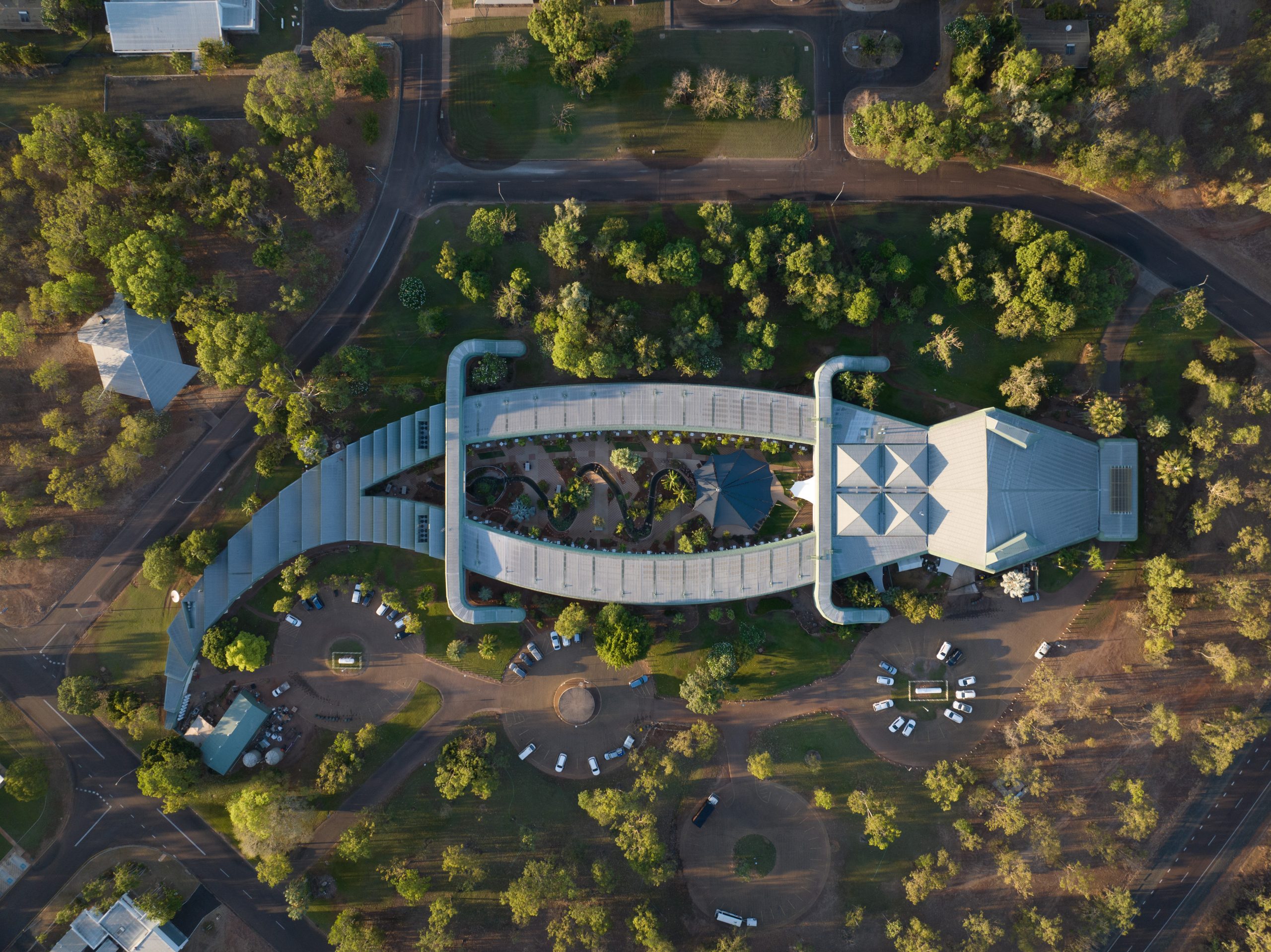

In addition to functional sophistication, Indigenous design often embeds a narrative in artefacts. A contemporary example of this aspect of Indigenous design is found in the Gagudju Crocodile Hotel in Kakadu (Figure 6). The crocodile is an important totem animal of the local traditional custodians, the Gaagudju people. With every aspect of the building reflecting the crocodile, include carparks shaped and located to look like crocodile eggs from the air, only the most insular visitor does not immediately understand the significance of this animal to the Gaagudju people.

Embedding narratives in design allow Indigenous peoples to demonstrate their knowledge, connection to country and history. More than including Indigenous art or motifs, Indigenous narratives or story telling in design influences the function and feel of a place/space. Embedded narratives also demonstrate the dynamic and continuing culture of Indigenous peoples beyond design.

Small scale, local materials and adaptive design

Indigenous design prefers small scale design, be it stream interventions or toolmaking, reflecting the design requirement to centre country and fulfil relational obligations.

The use of local materials supports small scale design. Fibres are widely used, being possibly the most common material globally (Page & Memmott, 2021). Not every place has an abundance of fibre. In places with an absence of grass fibres the locally abundant material, including rocks and tree fibres, are necessarily the preferred material. The reliance on local material encourages small scale design through the volume of material available at a place. That is, small scale artefacts require less material, reducing what is taken from country. If accessing materials from other places is not an option, or only small volumes of coveted materials can come from other places, small scale design is a practical way to ensure effective use of limited materials. There does appear a link between the size of an artefact and its capacity to be adapted, with larger artefacts, think bridges, dams or storm water systems for example, being less amenable to accommodating adaptive design features.

Adaptive design reflects the need for trial and error to achieve appropriate and effective artefacts. More than ensuring high performance of an artefact, the capacity to adapt designs is critical to the long-term survival of any community given the imperative to respond to changes in environmental conditions and knowledge systems. The waterwheel, for example, continues to be used in some Indigenous communities across southeast Asia, despite engineering alternatives such as pumps, for their capacity to continuously supply water without any fuel source. As people became more experienced with waterwheels they identified that sealing the wheel allowed more water to be moved. More robust materials have also been used to enhance the design function of the waterwheel. Consequently, the adaptive design capacity in these communities has seen the waterwheel remain entrenched in many waterscapes, despite the engineering solutions now available.

Small scale design based on local materials supports the adaptive reuse of both materials and artefacts. Large structures are not as readily convertible as small structures as their individual components can be too large or weighty to manipulate and manoeuvre, and these components may not be able to be put to another use as readily as smaller components. Page & Memmott (2021) provide evidence of structures that could be expanded or contracted in response to seasonal and other needs. That is, adaptive reuse is a design principle embedded in Indigenous practices, in contrast to its very recent inclusion in settler-state design principles.

Activity 2 Identifying non-Indigenous design on water country

As you walk water country, how may features in and around the waterscape that do not reflect Indigenous design principles can you identify?

For example, does the waterscape appear to have been modified with only human wants and needs in mind? Do the design features in water country have a sole purpose? Is the scale appropriate and material local? Can you see the story of water country?

Indigenous design principles – water specific

This section introduces Indigenous design principles with specific relevance for water country. These principles compliment those just discussed and do not detract from the recognition of country as indivisible. While the following design principles are specifically about water, they build on and work within those presented in the previous section.

Water and streams are of such significance they require a specific design focus. For example, Gammage refers to templates, defined as “plant communities deliberately associated, distributed, sometimes linked to natural features, and maintained for decades or centuries to prepare country for day-to-day working” (2011:xix). Water, particularly in creeks, could be used as a template “anchor” (Gammage, 2011:222), to extend water’s availability across time and a range of environmental conditions. Templates are not about dividing country but supporting country’s indivisibility. As such, templates represent designing with country.

Rivers as kin

Relationality is the basis of recognising rivers as kin. Every entity enmeshed in the web of relationships forming individual countries is sentient. Many entities are integral members in human kinship systems. Totemic relationships are an example of Indigenous kinship systems. Rivers and water are entities widely regarded as kin. Wiradyuri people in southeast Australia describe themselves as fresh water people; the people of three rivers. One of these rivers is marrambidya (currently called the Murrumbidgee River). The wiradyuri translation of marrambidya is big/good friend.

The Tlingit people in North America consciously cultivate a “powerful intimate and spiritual relationship” (Hayman, James, Wedge & Katzeek, 2017:222) with many more-than-human beings. Those who cultivate such a relationship with water learn deeply about it, and appreciating water as an individual. They also hold the obligation to identify and articulate things that may damge the relationship. The different ways of understanding water and rivers offered in these examples transforms the nature of design questions asked and solutions proposed. If you have cultivated, and are obliged to maintain, a deep relationship with water or see the river as your good friend, you simply cannot treat water or streams as sites for human-centred manipulation and extraction.

Don’t build on floodplains

First Nations people have been telling settler communities since their arrival to respect rivers by not building on their floodplains. While this principle may seem self-evident, if only to access the fertile farming soil of floodplains, it is about respect. Respect for the rivers, streams and creeks to express their sentience. This principle acknowledges the animacy of country, and that rivers and streams, as kin and country, have the right to flood and not be controlled.

Nothing attached permanently to stream bed or banks

This principle supports the prohibition on building on floodplains. Prohibition of permanent design artefacts on beds or banks ensure the range of biological, chemical and physical processes in play in water country are not affected by human-centric design. For example, channel bank storage, an important process occurring in channel banks ameliorating in-channel event flow, has a critical role moving water between ground and surface sites and performs water treatment functions. Channel bank storage processes are extinguished when urban streams are converted to storm water channels with impervious armouring such as concrete. Importantly, leaving channel beds and banks free of permanent design features allows the stream to express the flow regime and course of its choice.

Pre-1788, there would have been many water interventions designs. For example, Gammage refers to a “duck under” (2011:26) which, from assembling logs and sheets of bark, was one of the designs allowing water to be temporarily (re)directed. In the 21st century, new designs using Indigenous science and design principles are required to manage the impact of setter-state science and design on waterways. My research incorporated installing artificial channel bank storage sites (Figure 7) in a creek converted to a storm water channel, to replace the event flow storage role of this process.

Don’t permanently change flow patterns or stream course

To permanently change stream course or flow patterns is regarded as disrespectful to water’s rights as a sentient entity. Temporary modifications are acceptable, particularly when they extend water availability to food and drinking water sites such as wetlands.

Permanent changes to stream course generate unintended consequences affecting the web of relationships that is country. Water remembers the path, and will try to follow it. The consequences can range from: the catastrophic failure of meters of stream banks and bed armouring of materials considered permanent, such as concrete or rocks being ripped up during a large event flow; to the trickle of subsurface flow through concrete armouring into channel flow (Figure 8).

Indigenous water country design principles are a stark contrast to those of settler-state design. Each set of design principles reflects how water and rivers are understood in the respective design framework. Vastly different waterscape outcomes are the consequence of these difference. For example, dams, channel diversion, storm water systems and other water management features of the settler-state design framework, including pumps and pipes built into stream banks and beds are problematic in terms of Indigenous design. Even when settler-state water designs seek to mimic nature, such as renaturalizing or daylighting streams, these projects are expensive and highly engineered, with the stream given a course to follow. Settler-state design principles do not regard streams as independent, kin related entities able to set and follow their own course.

This short section indicates how deeply waterscapes are influenced by design principles. The principles inherent in settler-state design tend to support highly controlled waterscapes reflecting human needs. By contrast, Indigenous design principles aspire to design for country, where human needs are not the highest priorities, water is regarded as alive and rivers as kin.

Activity 3 Identifying Indigenous design on water country

As you walk water country, how many features in and around the waterscape reflecting Indigenous design principles can you identify?

In this case you are looking for designs that includes features such as having more than one purpose, use local materials and built at a scale that is reasonable and relevant. What water country designs can you identify that treat streams/rivers as kin?

Summary

The beliefs and values represented in the Indigenous water design principles are an extension of the general principles outlined early in the chapter, including centring country and relationality. Engaging with Indigenous design principles generates design problems and artefacts fundamentally different to those of settler-state design. These differences are the physical output of the fundamental philosophical difference between a transactional and relational understanding of the world. Using Indigenous principles supports crafting designs and artefacts that centre country and allow streams to run free. Thus, the decision a designer makes about which principles to use matters.

Doing the three activities provided in this chapter will guide designers in critically applying design philosophies and practices in their work. Completing the following exercise is an opportunity to deepen and extend designers understandings of both Indigenous and settler-state design principles, and how each influences the waterscape. A short reference list is provided to support independent research.

Final exercise

This exercise could be used as an assessment piece, or a way to bring together the three exercises in this chapter.

Reflecting on the different design approaches identified in the water country you walked in the previous activities, select an existing water storage system and assess it against the design principles presented in this chapter. What are some benefits of each design approach? What are some of the limits or problems associated with each design approach.

Note: All images provided by author and not licenced for reuse.

References

ACT Government. (n.d.). Waterway restoration – Curtin (upper Molonglo Catchment). https://www.environment.act.gov.au/water/ACT-Healthy-Waterways/healthy-waterways/sites/waterway-restoration-curtin-upper-molonglo-catchment

Gammage, B. (2011). The Biggest Estate on Earth. Allen & Unwin.

Harriden, K. (2023). Working with Indigenous science(s) frameworks and methods: challenging the ontological hegemony of ‘western’ science and the axiological biases of its practitioners. Methodological Innovations 16(2), 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/20597991231179394

Hayman, E., James, C., Wedge, M. & Katzeek, D. (2017). I yá.axch´age? (Can you hear it?), or Héen Aawashaayi Shaawat (marrying the water): A Tlingit and Tagish approach towards an ethical relationship with water. In. F. Ziegler & D. Groenfeldt (Eds.), Global water ethics: Towards a global ethics charter. (1st ed., pp. 217-242). Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315469690

Indigai, D. (2024). Drone.jpg [Photograph]. https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fo/v32bpc1qnflg46wb51jzi/AJbuqNgpsHboLlqlbLv-aWg?dl=0&e=1&preview=DRONE.jpg&rlkey=ogn367w1hciuyl3wniqt6dsru.

Marshall, V. (2017). Overturning Aqua nullius: Securing Aboriginal water rights. Aboriginal Studies Press.

Memmott, P. & Page, A. (2022) Materiality and design in Aboriginal engineering. In C. Kutay, E. Leigh, J. Prpic & L. Ormond-Parker (Eds), Indigenous engineering for an enduring culture (pp. 319-348). Cambridge Scholars Publisher.

Page, A., & Memmott, P. (2021). Design : Building on Country. Thames & Hudson Australia.

Tynan, L. (2021). What is relationality? Indigenous knowledges, practices and responsibilities with kin. Cultural Geographies, 28(4), 597–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/14744740211029287