15 Humanitarian engineering skills: A perspective from Engineers Without Borders, Australia

Sai Rupa Devarapu

Working for a fairer and more equitable future in the face of social inequality and environmental degradation remains the greatest challenge for engineers of our era. Humanitarian engineering, at its core, is both an approach and a discipline that seeks to strengthen engineering principles to address global challenges and improve the well-being of the planet and its people. Humanitarian engineering, as practised and advocated for by organisations like Engineers Without Borders (EWB) Australia, aims to address the closely interwoven social and technical challenges faced by communities worldwide, including First Nations.

EWB takes a community-centred approach to engineering practice to bridge First Nations-identified gaps in access to health, wellbeing and opportunity. Since 2009, EWB has worked with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in Queensland, the Northern Territory, South Australia and Western Australia on a range of community-identified projects.

We believe this provides an opportunity for engineers to also work with a highly skilled low-tech society that places sustainability at the heart of its engineering. If you consider what engineering would be like if it was developed from a foundation of sustainability, it would inevitably resemble the engineering of the First Nations, hence this is an excellent learning space. Moreover, the work is productive as the designs we develop with community often go on to be used by the group they were designed with.

However, that work requires various skills that are not taught in technical units. This chapter outlines 10 essential skills for effective humanitarian engineering practice, both in the context of Engineering on Country, and more broadly:

- Work alongside communities to understand the context

- Engage in collaborative and empowering partnerships

- Value and integrate multiple knowledges and ways of thinking

- Mind your language

- Focus on strength-based resilience and problem solving

- Leave no one left behind

- Promote cultural safety

- Lean on multi-disciplinary approaches

- Rethink project management to enable relationships

- Integrate environmental protection, climate action, and engineering

Work alongside communities to understand the context

EWB recognises and acknowledges Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People as the first engineers and scientists of this nation, caring for Country sustainably for as much as 65,000 years. As such, Engineering on Country (EoC) is not about imposition of Western ideas; it is about walking alongside and supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People to pursue their aspirations to live and thrive on Country, facilitated by equitable access to appropriate engineering, technology and infrastructure.

When working with Indigenous communities, humanitarian engineers must continually seek to understand and appreciate the historical, cultural, social, and environmental contexts in which these communities exist. Such understanding helps to establish respectful relationships and ensure that engineering interventions are appropriate and sustainable. At the heart of this approach is trust – an expansive, multi-disciplinary and multi-faceted term, with most definitions involving a combination of relationships, expectations, and the behaviours linked to those expectations (Notter, 1995, p. 4). As Feltman (2011, p. 7) writes, trust often involves ‘choosing to risk making something you value, vulnerable to another person’s actions.’ As such, working alongside communities comes with great responsibility to listen to, seek to understand, and centre their values before imposing our own values.

Exercises

What local community groups are in your area? Does anyone at your university or employer have any links with a group, through friendship, a previous project, anything. What are their needs and what could you do to assist in supporting that developing, either technology, labour, or just support.

- What group can you contact?

- What skills do you have to offer them?

- Keep your project within your skills and ability to complete the design and implement in community.

Engage in collaborative and empowering partnerships

Engineers Without Borders Australia recognises the importance of working with First Nations communities in a collaborative and empowering way. Through the EoC program, EWB aims to support communities in identifying and addressing their engineering requirements.

Engaging in collaborative partnerships with real involvement of all parties is a fundamental principle of humanitarian engineering in general and is amplified when working with First Nations communities. Engineering programs that centre the interests of community members in decision-making processes through involving members throughout the process can create greater agency and empowerment, active participation in the engineering projects, and foster self-determination with First Nations supported by technology.

This approach recognises that First Nations are the experts on their own needs and aspirations. By valuing and incorporating traditional knowledge, engineers can design and implement engineering solutions that are not only technically sound but also culturally appropriate sustainable and valued by community.

Cultural context reflection

Choose a current (or recent) project or course where you have had some engagement. Re-read the project/course materials and build a list of items that you can see were ignored or avoided because of specific pre-set requirements.

Now applying this EWB approach to thinking, what might you do now or in the future in regard to such items?

Value and integrate multiple knowledges and ways of thinking

As engineers, we are typically taught to focus on numbers and figures – the language of litres, kilonewtons and torque is our comfort zone. Rarely are we called on to think and engage far beyond what can be observed and measured. Yet the ability to integrate social with technological thinking is among the most important keys to unlocking humanitarian engineering. It does require multiple different understandings of knowledge, and the ability to hold them all as valid and valuable at the same time.

The typical engineering approach represents ‘positivist’ thinking. Positivist thinking is one epistemological approach, but there are other ways of understanding the world and developing knowledge that can impact engineering decision making. Beyond yield strength or balancing forces, humanitarian engineering incorporates considerations like perspective, values, and justice – considerations that have a massive impact on how we live and work but are not readily measured (McArdle, 2022). Rather, humanitarian engineering requires what we call constructivist thinking, which still draws on those observable, measurable aspects of the world around us, but at the same time acknowledges that the different ways in which people interpret and make sense of that world also matter. It is important to keep this duality of observation and perspective in mind because it is not just theory, it has practical implications for how we work as engineers. Forrest and Cicek (2021, p.2) put it this way:

The approach to problem solving in engineering courses focuses on repetition of mathematical problems. These problems are distinct in their subject matter and their requisite mathematical formulae, but are all generally approached the same way. Problem solving is treated as a fairly simple algorithm to navigate calculations, often under stable conditions. Such an approach neglects the fact that an engineer should engage with other perspectives to understand a problem fully. Multi-perspective thinking, which is the recognition that various perspectives exist with respect to an event, idea, or problem, can influence an individual’s problem solving (Wang et al., 2006). … In an analysis of creative problem solving strategies, perspective taking, or considering more deeply the needs of another person (generally a stakeholder), was found to be strongly associated with developing a diverse array of creative solutions, which is an outcome more likely to produce useful solutions (Rubenstein et al., 2019).

In no small part, integrating knowledges and ways of thinking is difficult because it means admitting that we may not have the right answer; that our solutions to problems may be inadequate; or that we may not always have all the data we want and thus find the problem hard to understand. These acknowledgements are uncomfortable, and it can be tempting for engineers to seek comfort in the certainty of numbers and parameters. But that discomfort comes from the power and privilege embedded in the ‘normal’ ways of doing engineering, whereas humanitarian engineering is about breaking down those norms to reveal and address social inequity. For instance the positioning of First Nations communities as rightsholders rather than stakeholders helps change consultations and collaborations.

Key Takeaways

We are seeking new ways from old ways as we are in crisis. We have been supporting an approach to our earth that is not sustainable and does not even respect that resources are limited.

- What are Australia’s most evident resources

- How can we maximise their usefulness and minimize waste within a circular economy

If we want to practice humanitarian engineering in substance, not just in rhetoric, we need to put energy into aligning our values with our practice, and not turning a blind eye to social inequity that engineering can bring about. As Brown (2018, p. 184) puts it, ‘Daring leaders who live into their values are never silent about hard things’. Humanitarian engineering facilitates more effective and successful engineering projects because it demonstrates respect for differences in cultures and ways of working.

Importantly, incorporating First Nations knowledges into engineering practice is not only about the ‘what’, but also the ‘how’ (Yunkaporta, 2019). Too often, mainstream science risks viewing such knowledges as simplistic, when if anything it can be the other way around. The complexity and nuance of Indigenous systems thinking can be difficult for Western science to comprehend within its existing paradigm.

It is for these reasons that Engineering on Country emphasises valuing and incorporating First Nations knowledges as a critical aspect of working with these communities. By recognising the wisdom and expertise that Indigenous communities have fostered across many millennia, engineers can gain a deeper understanding of the intricacies and complexity of systems and environments. This knowledge can profoundly inform the design and implementation of engineering solutions, ensuring that they are contextually appropriate, sustainable, and community-driven. By engaging with Indigenous community members in ways that break down the unhelpful power structures of who is the ‘knowledge-holder’ and who is the ‘listener’, to instead emphasise both-way knowledge sharing, an Engineering on Country approach can avoid imposing solutions on communities.

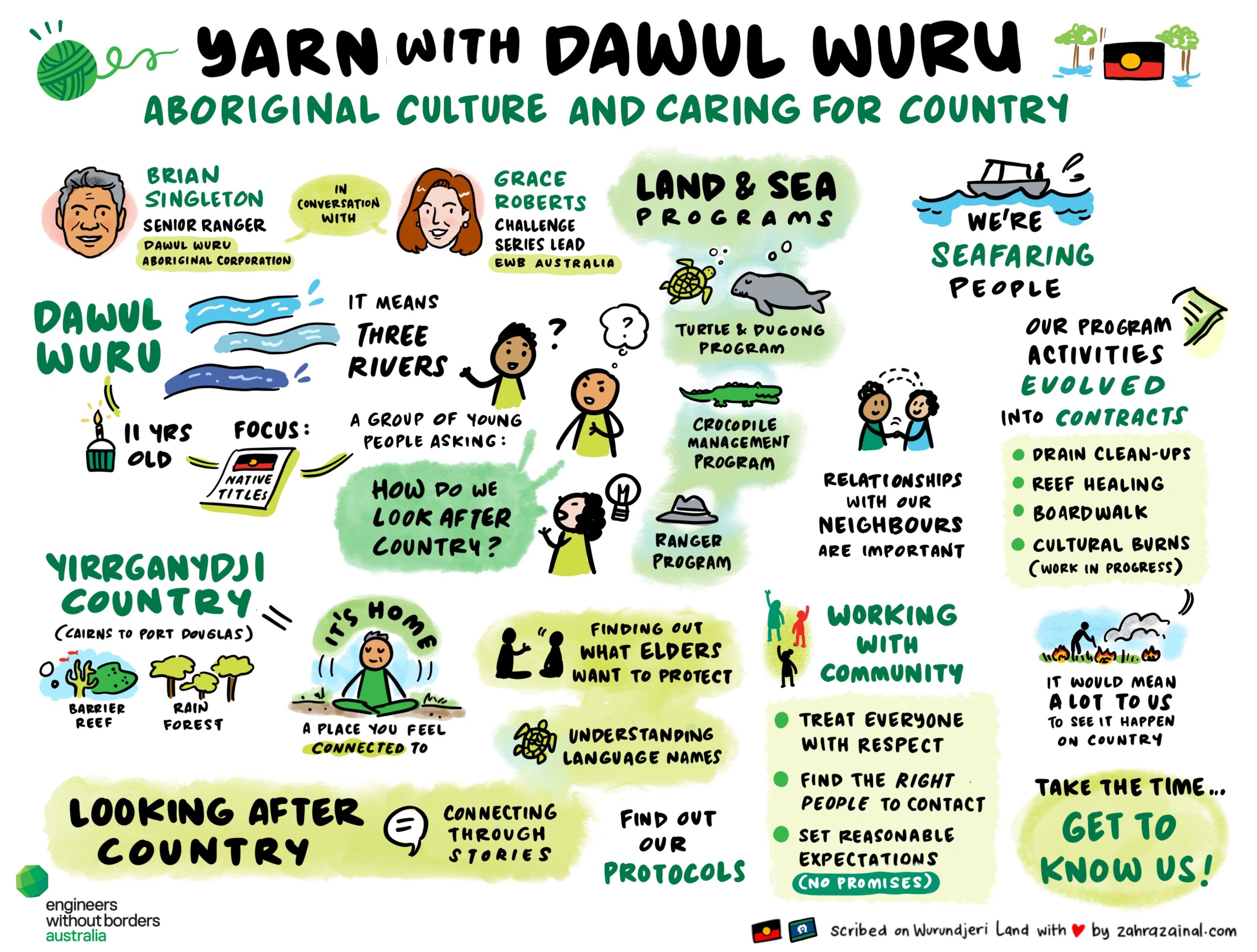

Figure 1. From Engineers without Borders, 2022 . Licensed for adaption and re-use under (CC.

Key Takeaways

Listening is hard especially when people speak a different first language. Cultural assumptions are a barrier to seeing other ways of doing and being.

- When listening to others try not to assume anything not said or ask when there is a chance to.

- When joining the conversation, you are confirming what you understand about what was told to you, it is a way of others see what you know from their contribution.

- Both-way learning is where you listen, wait, then explain what that means to you, so both can understand the others perspective and values. Both ways need explaining and both ways have equal value.

Mind your language

The language we use is central to how engineers learn from and share knowledge. For that reason, paying attention to the language we use is an essential skill for humanitarian engineers.

In his book ‘Sand Talk’, Tyson Yunkaporta (2019, p. 21) highlights the trouble of discussing problems in English.

English inevitably places settler worldviews at the centre of every concept, obscuring true understanding. For example, explaining Aboriginal notions of time is an exercise in futility as you can only describe it as ‘non-linear’ in English, which immediately slams a big line right across your synapses. You don’t register the ‘non’—only the ‘linear’: that is the way you process that word, the shape it takes in your mind. Worst of all, it’s only describing the concept by saying what it is not, rather than what it is. We don’t have a word for non-linear in our languages because nobody would consider travelling, thinking or talking in a straight line in the first place. The winding path is just how a path is, and therefore it needs no name.

At the very least, this calls for engineers to emphasise what we call reflexivity, the intentional consideration of specific ways in which our engineering work is influenced by our own histories, familiarities, world views, and perspectives (Yardley, 2015).

Reflection:

Next time you’re in a project management class or meeting, pay attention to the language being used. Think closely about where certain terms might have come from, and if that could have any subtle implications. For instance, when going to the ‘kick-off’ meeting, you could reflect on who would have traditionally participated in a ‘kick-off’. Or, in the projects ‘control phase’, does ‘controlling’ allow for both-way knowledge sharing and partnerships, listening, and adaptation? (Atkinson et al., 2021; Dix & Visser, 2022; Gollan & Stacey, 2021).

Focus on strength-based resilience and problem solving

The concept of resilience is a common term in engineering practice, and while there are many definitions, it is often used to describe the ability of a system to absorb, cope with, and/or recover from adversity. That’s fine if you’re strength-testing reinforced concrete so that your building design can withstand an earthquake. But we can go deeper, why do we want the building to stay up?

The answer is because we want people to be able to use the building safely even during the earthquake. People are the reason we talk about resilience.

Yet, if we talk about resilience as coping, we suggest that people are passive or helpless. But people and communities are not helpless – they have strengths, preferences, and agency which must be considered in humanitarian engineering. Taking this a step further, even adaptation – a term we often hear in relation to a changing climate – can be problematic. When talking about resilience, we need to be mindful of who is responsible for shouldering the burden. If we suggest that the person or community facing adversity is responsible for adapting to it, we deflect scrutiny from our own thinking, designs, and behaviour which might in fact be contributing the problem (Chandler & Reid, 2016; McArdle, 2022).

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Eleanor Ostrom, a trailblazing environmental scientist who won the Nobel Prize for Economic Sciences in 2009, summed it up well. Instead of focusing on the helplessness of a situation, she instead chose to focus on people’s strengths and aspirations for change. In her words: ‘I would rather address the question of how to enhance the capabilities of those involved to change the constraining rules of the game to lead to outcomes other than remorseless tragedies’ (Ostrom, 1990, p. 7).

Examples

There are many examples of the way that over catering to the negative aspects of projects we can ignore the value that community can bring.

- What skills/training is there in the community already which can contribute to the project or design of the project

- What new knowledge is being provided on the ground to the technology you are working with, are these examples of local technology or a new use of western technology that can inspire change

Enhancing capabilities is a very different way of thinking about engineering than, say, fixing a problem. This mindset is not solely focused on a recipient community benefitting from outside assistance, but refers to all those people taking part in a system and, crucially, redistributes the burden of responsibility for resilience onto the broader society. This leads us to a crucial point, resilience is, by its nature, social. An inherent element of community resilience is the way in which they are supported by their community. The ways in which people are supported by infrastructure, services and systems that they use every day are crucial in our resilience to adversity. The more accessible and appropriate our engineering designs and the more inclusive and just our work, the more resilient the people and communities who use them will be.

Leave no one left behind

All engineers have a responsibility to consider the impact of our work on the communities that use them, or in some cases, don’t or can’t use them. This is why humanitarian engineering talks about ‘leaving no one behind’.

To leave no one behind is language that comes from the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It focuses our attention on the fact that not all people have equitable access to goods, services, and infrastructure, and ‘calls for all stakeholders to intensify their efforts to narrow existing gaps’ (Bennett, 2020, p. 9). It’s also the reason that EWB says its purpose is for ‘Harnessing the potential of engineering to create an equitable reality for the planet and its people’ (Engineers Without Borders Australia, 2020).

When it comes to engineering, equity goes hand in hand with principles of fairness, and participation, and justice (Sultana, 2018). Like resilience, these principles are heavily dependent on relationships, and are contextual rather than universal (Boelens, 2015; Roth et al., 2014)

What this means for the engineering profession is that the people who use and access the infrastructure and services we design are not only interested in the material aspects of buildings and roads, but also share in the fairness of our work (Lauderdale, 1998, p. 9). Often, engineering work is about deliverables – constructing that bridge; or reaching that efficiency target. But fairness is not the sort of concepts we’re taught in most engineering degrees, and isn’t often talked about in project management meetings.

Key Takeaways

What has to change in our approach to our designs

- Who should contribute to designing?

- Who can be employed on the development?

- Who should be engaged in the implementation?

Sometimes, leaving no-one behind is not efficient. Sometimes it’s arduous, or expensive. It’s rarely financially economical to make sure people living far from the city have equitable access to the facilities enjoyed by people in large urban centres. Sometimes listening to the concerns of all water users along a shared river basin is time-intensive, and frequently uncomfortable. It can take active engagement to look for social inequity. It often takes significant funding to engage with issues of injustice. It is essential that humanitarian engineers build our skills in areas that will help us to engage positively with these issues

Promote cultural safety

Engineering on Country acknowledges the notion that ‘cultural safety is a pre-condition for First Nations of Australia to access, be involved in and thrive within workplaces and services’ including the contexts of engineering project work (Gollan & Stacey, 2021).

Developed by Māori nurse Irihapeti Ramsden (2002) in Aotearoa/New Zealand, the concept of cultural safety has been adapted for First Nations Australia contexts and communities (CATSINaM, 2017; Gollan & Stacey, 2018, 2021; Lowitja Institute, 2018). As Gollan and Stacey (2021) articulate, ‘A culturally safe environment is created in policy development, evaluation, research and service design and delivery when the circumstances are in place’ (S. Gollan & K. Stacey, 2021)

As with the EoC approach to community resilience discussed above, it is important to remember that the responsibility for cultural safety is heavily rooted in genuine, balanced, both-way relationships. Accordingly, non-First Nations engineers ‘have a high level of responsibility as well as significant capacity to create culturally safe environments’ (Gollan & Stacey, 2021, p. 5).

Extending on this, cultural safety situates humanitarian engineering skills as an ongoing process, rather than an endpoint or definitive output. Where skills in this area are sometimes referred to as cultural competency, humanitarian engineers should approach safe engagement with First Nations communities as dynamic and will, after long preparation, be informed by communities themselves. This not only leads to more effective and sustainable solutions but also fosters trust, collaboration, and empowerment as central to humanitarian engineering work.

Exercises

Consider a large-scale engineering project in, or affecting your community

- Examine the ethical considerations embedded within Western engineering practices such as risk assessment, cost-benefit analysis, and legal compliance.

- Discuss how Western engineering often priorities individual rights, property ownership and liability avoidance

- Compare this with Indigenous ethical frameworks, which may prioritize collective well-being intergenerational equity and connection to the land.

- Reflect on the ethical dilemmas that arise when Western and Indigenous perspectives intersect in engineering projects

With cultural competency training, engineers will engage in meaningful and ongoing dialogue with community members, elders, and local histories. It is important to seek opportunities to learn about Indigenous tradition and values and strive to build relationships based on mutual respect and trust. Integrating Indigenous studies and perspectives into the engineering curriculum is crucial for fostering cultural competence and understanding; and these competencies are essential to effective engineering practice.

In the engineering industry, we rightly talk a lot about workplace health and safety. But how often do we think about culture in that context? Safety is physical and cultural. Take water, for example: the way in which water is managed is not only about drinking and cooking – water is also about health and wellbeing. This can be seen in the barriers to teaching on Nari Nari Country when water is scarce:

The knowledge transfer from the elders to the younger generation can’t happen because they [the community] can’t go back to those sites on the river where there were waterholes and there were stories attached to that. No one wants to go and see a waterhole and talk about a story when there’s no water (Woods in McArdle 2022, p.169).

Health and wellbeing considerations are thus paramount in humanitarian engineering projects and are as pertinent as ever when working with Indigenous communities. Engineers must prioritise the safety of community members by conducting thorough risk assessments, implementing appropriate safety measures, and addressing potential health hazards. These must extend beyond physiological hazards, where health and safety analysis incorporates and respects Indigenous practices and beliefs.

Lean on multi-disciplinary approaches

One of the key distinguishing characteristics of humanitarian engineering is its multi- or even trans-disciplinary nature. Undoubtedly incorporating the fundamental physical sciences, life sciences, and mathematics expected of the engineering profession, humanitarian engineering expands our understanding of problem solving into fields such as social sciences, public health, psychology, education, political science and peace and conflict studies, among others.

Approaching engineering beyond its familiar technical efficacy opens space for us to also consider the interconnectedness of social, cultural, and environmental dimensions of the challenges faced. Collaboration is a cornerstone of humanitarian engineering, necessitating the ability to work with diverse groups inclusive of non-engineering experts, community members, individuals of various genders, and those from different cultures and identity groups. The effectiveness of humanitarian endeavours relies deeply on interpersonal relationship to collaboratively address complex issues of social justice embedded in technology, infrastructure, products and systems.

Learning Objectives

What are the enduring aspects of First Nations knolwedge and science, that provide similarity across many countries and Nations. These are key to any real collaboration on projects and any integration of sustainable thinking

- Respect and Reciprocity

- Flexibility and minimalisation

- Local based solutions based on deep knowledge of local systems

- Holistic knowledge collection through stories

What else?

Rethink project management to enable relationships

Project management skills are also crucial in humanitarian engineering projects. Engineers must be able to effectively plan, organise, and coordinate projects while considering the specific needs and priorities of the community.

This includes engaging in meaningful consultation and collaboration with Indigenous community members throughout all stages of the project, from initial planning to implementation and evaluation. By incorporating community members as active partners, engineers can ensure that the project is culturally appropriate, respectful, and aligned with the goals and values of the community. Additionally, engineers need to consider the historical and ongoing impacts of colonisation on Indigenous communities. This awareness can help in mitigating potential power imbalances and promoting equitable partnerships, allowing for more effective project management and sustainable outcomes.

Integrate environmental protection, climate action, and engineering

Humanitarian engineers must always prioritise environmental and social considerations in their projects. Or even better, recognise the mutual complementarity of each component, whereby environmental protection, climate action, and humanitarian engineering each supports the success of the others. Similarly, neglecting one component undermines the others, which emphasises the need to integrate approaches to each.

Recognising the benefit in breaking down silos can open space for more systemic and holistic responses to addressing community needs and aspirations. For example, integrating climate action and environmental protection into engineering thinking and practice, rather than a more siloed approach of triple bottom line can not only improve community outcomes, but in the process also reduce duplication and optimise use of limited resources. ‘The degree of integration will vary based on the needs and priorities of each [region or community]’ but simply prioritising integration will open space for mutually beneficial outcomes (Pacific Community [SPC] et al., 2016, p. 7)

Different actors in the humanitarian engineering space will be at different stages of their journey. Just as different organisations have different roles and resources, an empathetic approach that meets people and organisations where they are on their path can foster inclusivity in moving the engineering sector forward. An inclusive engineering sector that advocates for greater listening, learning and knowledge sharing is encouraged to bring about positive change.

Exercises

What would change in your latest project if you integrated more envirnonment and climate considerations:

- What materials would you use?

- How big would your project be, can you separate it into parts?

- Who would you engage on the project?

- How would you implement the project?

- How would you convince other engineers to implement your approach?

Note: Country, capitalised, is described by AIATSIS as ‘the term often used by Aboriginal peoples to describe the lands, waterways and seas to which they are connected. The term contains complex ideas about law, place, custom, language, spiritual belief, cultural practice, material sustenance, family and identity’ (AIATSIS (2024) What is Country?)

References

Atkinson, P., Baird, M., & Adams, K. (2021). Are you really using Yarning research? Mapping social and family yarning to strengthen Yarning research quality. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 17(2), 191–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/11771801211015442

Bennett, J. G. (2020). Leave no one behind: Guidelines for project planners and practitioners. GIZ.

Boelens, R. (2015). Water, power and identity: The cultural politics of water in the Andes. Routledge.

Brown, B. (2018). Dare to lead: Brave work, tough conversations, whole hearts. Vermillion.

Chandler, D., & Reid, J. (2016). The neoliberal subject: Resilience, adaptation and vulnerability. Rowman & Littlefield.

Congress of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nurses and Midwives (CATSINaM). (2017). Position statement: Embedding cultural safety across Australian nursing and midwifery.

Dix, L., & Visser, J. (2022). COFEM Learning brief series: Feminist project management. Coalition of Feminists for Social Change.

Engineers Without Borders Australia. (2020). Towards 2030 strategy. https://ewb.app.box.com/file/731586765509?s=3omxnseuws49217jct6xfassb7pvvvy4

Feltman, C. (2011). The thin book of trust: An essential primer for building trust at work. Thin Book Publishing.

Forrest, R., & Cicek, J. S. (2021). Rethinking the engineering design process: Advantages of incorporating Indigenous knowledges, perspectives, and methodologies. Canadian Engineering Education Association (CEEA).

Gollan, S., & Stacey, K. (2018). Personal and professional transformation through cultural safety training: Learnings and implications for evaluators from two decades of professional development. Australasian Evaluation Society Conference, Launceston. https://www. aes.asn.au/images/images-old/stories/files/ conferences/2018/16GollanSStaceyK.pdf

Gollan, S. & Stacey, K. (2021). First Nations cultural safety framework.

Australian Evaluation Society.

Lauderdale, P. (1998). Justice and equity: A critical perspective. In R. Boelens & G.Davila (Eds.), Searching for Equity: Conceptions of Justice and Equity in Peasant Irrigation, (pp. 5–10).

Lowitja Institute,. (2018). Journeys to healing and strong wellbeing: A project conducted by the Lowitja Institute. Lowitja Institute. https://www.lowitja.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/lowitja_consulting_journeys_to_healing_report.pdf

McArdle, P. I. (2022). Transforming water scarcity conflict: Community responses in Yemen and Australia. The University of Sydney. https://hdl.handle.net/2123/29933

Notter, J. (1995). Trust and conflict transformation. Institute for Multi-Track Diplomacy.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

Pacific Community (SPC), Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPRE), Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat (PIFS), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR), & University of the South Pacific (USP). (2016). Framework for resilient development in the Pacific: An integrated approach to address climate change and disaster risk management. https://www.resilientpacific.org/en/framework-resilient-development-pacific

Ramsden, I. M. (2002). Cultural safety and nursing education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu.

Roth, D., Zwarteveen, M., Joy, K., & Kulkarni, S. (2014). Water rights, conflicts, and justice in South Asia. Local Environment, 19(9), 947–953. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2012.752232

Rubenstein, L. D., Callan, G. L., Ridgley, L. M., & Henderson, A. (2019). Students’ strategic planning and strategy use during creative problem solving: The importance of perspective-taking. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 34, 100556 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2019.02.004

Sultana, F. (2018). Water justice: Why it matters and how to achieve it. Water International, 43(4), 483–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2018.1458272

Wang, Y., Dogan, E., & Lin, X. (2006). The effect of multiple-perspective thinking on problem solving.

Yardley, L. (2015). Demonstrating validity in qualitative psychology. In JA Smith (ed.). Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods. SAGE Publications, pp. 235-251. http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/id/eprint/54781

Yunkaporta, T. (2019). Sand talk: How Indigenous thinking can save the world. Text Publishing.