4 Negotiating the assumptions and identity tensions surrounding third space academics/professionals

Puvaneswari P Arumugam

Introduction: What is the fuss about third space practitioners?

Video transcript

Hi, I am Puva P Arumugam, and I am a third space academic – I am a Lecturer, Learning Futures in an Australian university and I belong to a very prominent workforce in the higher education sector known as third space practitioners. As an academic, I am very interested in the research involving third space practitioners. Recently, colleagues asked me what the fuss was about third space practitioners in the higher education landscape and why third space practitioners warrant any research interest. My answer is that third space practitioners will always be an ever-developing important aspect of the higher education workforce, and there is no better time than now to be involved in this research.

Among the many hats that I wear in my role, I am an academic lead of teaching and learning course and unit development projects and I enjoy my work because I get to work with a variety of discipline-based academics and projects, and I can indulge in lifelong learning in my role. As a third space academic, I am also constantly working to make an impact with the work that I do and to bring about awareness of my hybrid identity in the higher education teaching and learning space.

As this textbook is aimed at providing an inclusive and diverse learning experience for learning designers who also come under the umbrella of third space practitioners (either as third space professionals or third space academics), it is right to point out that their roles have at times been perceived as an appendix to the discipline-based academics and/or higher education professional workforce. This perception causes assumptions, and these assumptions cause blurred boundaries in terms of professional identity and having a sense of belonging in the higher education landscape. As such, third space practitioners do often find that they have to navigate a fair bit of tension and challenges before completely understanding this space in which they operate.

I hope to unpack a few of the tensions and challenges and show what the fuss is about third space practitioners as I narrate through my own reflections of being a third space academic and by drawing references from literature and research that has been done in this space.

Who are these third space practitioners?

Third space practitioners, who are often referred to as third space professionals and third space academics, have been in the higher education landscape for quite some time now. A fair amount of research has been done across the globe regarding the work of third space practitioners, the liminal space they occupy and their identity in the higher education landscape. The work and presence of third space professionals has become more prominent through the work of Celia Whitchurch. Whitchurch (2008) highlights the mixed background and portfolios that third space professionals come from and how their appointments span across the domains of both academics and professionals. She highlights that because third space professionals are likely to have work experiences in settings external to higher education, third space professionals may feel a sense of outsider status. During the recent global COVID-19 pandemic, third space practitioner roles such as learning designers, educational technologists, educational developers, academic developers and instructional designers, to name a few, become increasingly necessary as higher education institutions moved to a more integrated learning environment and the roles gained popularity as a career choice (Heggart & Dickson-Deane, 2022). This chapter discusses details surrounding the professional identity of and the assumptions about the role of third space practitioners. It highlights the tensions and challenges faced by third space professionals and third space academics within the liminal space (Manathunga, 2007) they occupy within the higher education landscape and provides an ‘industry’ (i.e., working in the higher education space) perspective. This chapter also describes the difference between third space professional and third space academic roles and the way learning designers are perceived by traditional teaching staff, and how this perception affects the way they function in both roles. Using the lens of Homi Bhabha’s concept of ambivalence and liminal space (Bhabha, 1994), this chapter highlights certain tensions and challenges faced by third space practitioners in higher education as they navigate expectations and assumptions held by traditional institutional and discipline academics.

Your task

Let’s take a moment to reflect on your own practice and your experience of either being a third space practitioner or having worked with third space practitioners.

Using the Padlet activity ‘Navigating the tensions and challenges as Third Space Practitioners’, share your thoughts about the following questions:

What has been your experience of working with third space practitioners? Please feel free to share your own experience of being a third space practitioner within the higher education context.

Teaching and learning staff members in higher education

Video transcript

I didn’t really think I would end up being a third space academic. I actually stumbled into this role by chance. I worked as a casual academic for four years while completing my PhD. I truly enjoyed my role as an academic and just before my graduation I was acting as the unit chair for several units that were related to my area of expertise. After my PhD, owing to personal circumstances, I had to leave academia and I took a job in the corporate world. I brought to my corporate roles many transferable skills from my experience as a casual academic. I knew how to work technology, manage people, meet deadlines, prepare and deliver presentations and train and mentor people on the job.

The pay and work in the corporate sector were good, but deep down inside I knew that I wanted to work in academia as I didn’t want to ‘waste’ my PhD. Wanting to go back into academia is also a cultural thing for me. I come from Southeast Asia, and I grew up in a multicultural environment. And we are measured by our achievements. Having a PhD and being an academic do rank quite high in terms of personal achievement. I personally pursued a PhD because I wanted to be an academic. But with a niche discipline background like Cultural Studies and Performing Arts, it was hard to get back into that discipline. So, after 11 years of not being in academia, I returned to working in the university and took on a third space professional role as a Senior Educational Designer. Within a year, I applied for a third space academic role within a faculty in the university, and I became a Lecturer, Learning Futures.

I was very happy that I got an academic role, but there was also this sense of curiosity about what exactly I would be doing in this role.

Discipline-based academics

In many universities, the discipline-based academics (Manathunga, 2007), also known as traditional academics, experience a clear sense of belonging, because there is clear alignment between their professional identity, the job they do and the relationship these have to their discipline. Usually, discipline-based academics do not hold any teaching qualifications and they teach content based on their knowledge of the subject matter as it relates to the field, and they are usually trained in their area of expertise by way of working or research. Their role is to teach in the discipline they belong to with a minimum of contact time with students, and they must prepare, curate or develop the teaching materials and manage the administrative and content development related tasks that are attached to this role. These may include curriculum development, writing of assessments and rubrics, developing teaching plans and learning content, lecture and seminar teaching, as well as developing learning materials, marking, grading, producing final reports, sitting on academic committees, contributing to scholarship of teaching, presenting at conferences and collaborating with other institutions and getting grants from industry partners. This ties in very much with Boyer’s scholarship model, where ‘the priorities of the academic encompassed four main themes, namely: teaching and learning, integration, application, and discovery’ (Boyer, 1990, p. 2). Discipline-based academics are paid according to academic pay scales that recognise seniority. Of course, this is a general description, and the role of a discipline-based academic is by no means confined to these elements. However, it is important to note that many discipline academics love being academics. They are usually in ongoing roles and because they fit in this space very easily, they are happy to move from one higher education institution to another to continue to grow their career.

Casual Academics/session tutors

Another group of academics that are part of the higher education teaching staff are casual academics. This group is made up of aspiring academics who are doing their PhD or have just completed their PhD. They are generally seeking to become academics after completing study or working in the industry of their expertise. Casual academics often take on several roles in the university including those of tutors, seminar leaders, acting lecturers and acting unit chairs, depending on the need for teaching staff within their school and faculty. They engage in teaching and developing content as needed. They usually work on short-term contracts, and they do not enjoy the full remuneration benefits of paid leave in many institutions. They do not have to do the administrative work, but some might get paid to do it. They do engage in research and are eligible for awards and grants, depending on the particular higher education institution, but often this research is either in their own time or limited.

Professional staff

The next important group of teaching and learning staff would be the professional staff members who support administrative functions in the universities. These professional staff would be stationed in areas such as Finance, Student Enrolment, Human Resources, Timetabling, Library, Information Technology, Unit Site Development, Assessment Submission and Office Procurement. There is no research load for professional staff, and they can attend conferences and other professional learning opportunities to enhance their understanding of the higher education space without having to publish or engage in research. In Australia, professional staff do not have to work beyond agreed hours and they have flexibility to go full or part time. They, too, often consider the higher education landscape to be their home and place where they belong.

Third space practitioners

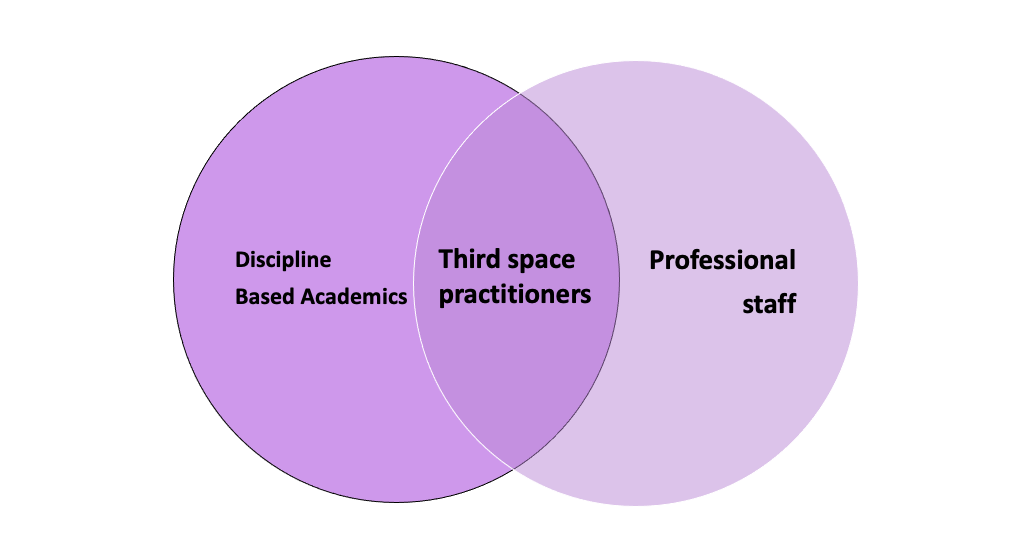

While professional staff in the past have provided support for administrative tasks, some of them have also, for the past two decades or so, crossed into the realm of preparing teaching and learning materials and co-designing teaching and learning with academics, hence navigating a space in between teaching and administration. They have become known as third space professionals (Whitchurch, 2008). Figure 1 shows the liminal space that is occupied by third space practitioners, who are often in both academic and professional roles. This pool of staff, owing to the hybrid space they occupy, have often struggled to find their place in the university and hence are often ‘homeless’ when it comes to finding their place in the university setting (Manathunga, 2007). Unlike the other categories discussed above, they often only have a very vague sense of belonging within the higher education landscape.

Third space professionals

Third space professionals are non-academic staff who come under the umbrella of third space practitioners. They might be educational technologists, or librarians, or school administrative staff who create or assist with the creation of teaching and learning materials to support teaching staff. These are often professional roles such as Educational Developer, Learning Designer, Instructional Designer, Educational Technologist, among others. Third space professionals have a varied educational background; many do have postgraduate qualifications, sometimes related to the discipline they work in. These roles are often categorised by Higher Education Worker (HEW) levels in Australia. They are non-teaching roles. They do provide capacity building or professional learning to teaching staff members, but not because they have a teaching component attached to their roles.

Third space academics

Video transcript

I recall an incident when an academic whom I had not worked with in the faculty met me as I was making my cup of tea in the shared kitchen. She asked: ‘What is it you do?’ I replied happily: ‘Oh, I help support academics in the faculty with their teaching and learning practices and material, I co-design their teaching and learning cloud site and I also help to review their assessment and rubrics, and I build academics’ capacity to transition smoothly into the blended teaching space.’ Her response shocked me: ‘Oh, I see … I am a real academic, unlike you. I teach students in class, we have to teach several units, and we have a research load that we have to do. It’s hard work. Very busy.’

I stood there looking at her blankly. I sort of missed most of the words after she said ‘real academic’. My thoughts were along the lines of: How am I not a real academic? Why am I not a real academic? I have a PhD. I teach. I work on several units. I write learning objectives, I care about students and their learning experience. I care about all the things she cares about. I have a research load and I am so busy too! How am I not a real academic?

Her reaction and response never left me and won’t leave me as long as I am in this role.

According to Smith et al. (2021), third space academic is a term used to describe roles that are held by non-discipline academics who are not necessarily subject matter experts although they support a wide variety of teaching academics from all disciplines with curriculum development, assessment and rubric design, learning design, content management, project management, and people and time management, and they have a research component as part of their workload allocation model. These academics have migrated from other disciplines (Manathunga, 2007), transferring their prior identities and knowledge from their home discipline into teaching. Karen Dowd and David Kaplan have categorised academics into several groups; two that relate to third space practitioners would be Mavericks and Connectors, as they are both listed as being boundaryless (Dowd & Kaplan, 2005). Dowd and Kaplan describe Mavericks as academics who are independent and seemingly unconstrained by the structural limitations of the tenure-track nature of academia; and Connectors are academics who perceive their roles to go beyond the traditional boundaries of teacher and researcher. Within this conceptualisation, third space academics would sit in between the parameters of being Maverick and Connector in terms of academic career types. Their career trajectories in terms of what they teach and learn are boundaryless, but they are bound by academic requirements to publish. Academics in these roles also have postgraduate qualifications including PhDs that might or might not be related to the discipline in which they work. In some universities they are described as Academic Developers, Senior Educational Developers, Learning Design Developers, among others, and they have teaching, service and research components attached to their roles. Their pay is classified according to academic pay scales and they follow academic promotion pathways. Given that discipline-based academics view them as not being ‘real academics’ owing to the lack of industry knowledge about what exactly they do, third space academics often find it hard to have a sense of belonging to their professional identity and to the higher education landscape.

Polymathic nature of the third space practitioners’ role

Video transcript

When I became a Lecturer, Learning Futures seven years ago, I struggled for the first four years when people asked me what my job was about. I would tell them that I am an academic in the faculty, but I don’t lecture in any of the units and I work with academics more than students. They would give me a puzzled look. I would quickly add that I am in an academic role, and I have a PhD in another discipline although I help to support teaching and learning in a completely different discipline. Usually I would have lost them at ‘I work with academics’. It was just too hard. No one understood the entirety of my role. So, I started to tell them I am a third space academic. Believe me, I didn’t do any research about this term when I first started using it – it just seemed apt for my role because I knew that if I called myself a third space professional, then discipline-based academics and those who aren’t familiar with that term would not take me seriously. But even now, people don’t get what exactly I do. What in the world does third space academic mean to the lay person? You are either an academic or you’re not! What is this blurred space that is attached to the role and identity?

Polymathic nature of the role

Similar to third space academics, the work that third space practitioners do can be categorised as unbounded. This distinguishes them from other professional staff (Whitchurch, 2008). Aranee Manoharan (2020) states that third space professionals are polymathic in their expertise. She argues that third space professionals are able to navigate multiple lifeworlds and disciplinary areas within a university. As such, they understand different professional motivations and are able to connect with a range of occupational dispositions. Polymathic (Manoharan, 2020) means to go beyond a singular specialisation and to function with multiple expertise. It is not a ‘jack of all trades and master of none’ proposition. On the contrary, third space practitioners, owing to the broad areas of teaching and learning projects that they work on, can have in-depth knowledge of more than one area of specialisation.

Table 1 shows the similarities and differences in role titles held by third space professionals and third space academics. However, there will be differences in work experience, understanding of position descriptions and expectations of the output for third space professionals and third space academics. Even within the same university, the roles of third space professionals and third space academics are not defined by a standard set of position descriptions and they often play a variety of roles within their capacity of supporting educational development. Hence, they are often expected to have a variety of skills, knowledge and practice about educational development, learning design, curriculum development and assessment and rubrics design. In the current higher education landscape, the lack of role clarity regarding the differences in expectations and functions may cause third space practitioners to become more liminal in terms of their understanding of their roles and their own professional identity.

| Types of roles | Third space professionals | Third space academics |

| Learning Designer | Yes | Yes |

| Librarian | Yes | No |

| Educational Technologist | Yes | No |

| Instructional Designer | Yes | No |

| Academic Developer | Yes | Yes |

| Senior Educational Designer | Yes | Yes |

| Educational Consultant | Yes | Yes |

| Lecturer, Central Teaching Team | No | Yes |

Text-based version of Table 1

Table 1 titled Examples of different titles and roles held by third space practitioners. The table has three columns and nine rows including the header row. Header row has ‘types of roles’, ‘Third Space professionals’ and ‘Third Space Academics’. The first row contains the learning designer.

What are the skill sets necessary to become a third space practitioner?

Video transcript

I was never trained to the job I am doing now. I picked up all the skills, all the good stuff about teaching and learning practices, over the last ten years as I worked my way across the realm of being a third space practitioner.

In my current role, I am very much involved in the designing, developing and deciding side of teaching and learning practices. When I first started as an academic developer, I had no clue what an LMS was, what terms like pedagogy and andragogy meant; for that matter, I had no idea what a flipped classroom was. But I have been exposed to all of them as an academic. I just didn’t know that what I was doing had names and theories attached to it.

Now, I am a fully-fledged higher education academic strategist – well, here’s an additional term to describe third space academics/practitioners like me, and I do call myself that in my LinkedIn profile description.

Heggart & Dickson-Deane (2022) present several skills for learning designers that are applicable to third space professionals. These skills include ‘prioritisation of communication and collaboration skills; we need to be able to make adaptive decisions, we need to be able to work in teams’. Very often, third space practitioners are involved in projects which are of differing scales. They can be short-term or one-off projects such as learning transformation or implementing a new learning management system (LMS), or they can be ongoing projects within a faculty or school such as subject development and/or professional development. Given the various projects that third space practitioners manage, they also need to know project management. They need to know how to manage their workload ebbs and flows. These are skills that are not picked up in courses but are only developed during work placements. These are the skills that discipline academics might not necessarily have in their skill set, depending on their discipline, and that is what makes third space academics less ‘academic’ in their view.

Your task

If you identify as a third-space practitioner, reflect on a situation where you had to explain your role and consider whether the reaction aligned with your expectations. Visit the ‘Navigating the tensions and challenges as Third-Space Practitioners’ Padlet activity to share your thoughts.

Navigating the liminal space

Source: Photo by Kristjan Kotar on Unsplash

Source: Photo by Kristjan Kotar on Unsplash

Video transcript

I am not sure if you have noticed that for those of us who have been to interviews for any third space roles, one of the questions will focus on how well we can deal with difficult academics. Here they are referring to discipline-based academics. I can’t see you, but I know that a few of you will be nodding. They have asked this question in all the interviews that I went for. And initially, I went home wondering, why are they asking about difficult academics? I am an academic and I don’t think I would be difficult. But when I took my first few roles, and started working with discipline academics, difficult academics made up a good proportion of the people I have worked with. These academics are not difficult people, but because they don’t understand my role, and they don’t understand how as a non-subject matter expert I can help them, they simply become difficult because they don’t want someone like me telling them how to teach their units.

Third space practitioners have been described as being in a liminal space within the higher education landscape as they work together with academics and professionals (Veles et al., 2019). Their roles are described as ‘liminal, binary/overlap or borderless’ (Veles et al., 2019, p. 77). Although Bhabha (1994) uses the term ‘liminal space’ to describe the feeling of dislocation experienced by both slave and master – the coloured and the white – purely in the context of post-colonial national identity, this idea of being in a dislocated space applies quite well to the liminal space occupied by third space practitioners in the higher education landscape.

According to Bhabha (1994), a liminal space is the space occupied in the stairways where it is neither at the top nor at the bottom. Third space practitioners are entrapped by their liminal space of not being a discipline-based expert when they work across various faculties and schools. They are often perceived to be ‘lesser’ than discipline-based academics, and university professional staff members and fail to see the value of their expertise in the area of teaching and learning. This is because they do not get the validation they deserve when they engage in their area of expertise. It can also be argued that discipline-based academics and professional staff members feel a sense of surprise, and discomfort at times, to find that their expertise and knowledge of subject matter content can be further enhanced when they are supported by third space practitioners to provide better teaching and learning experiences for both academics and students. Hence, these three sectors that currently exist in the higher education workforce often find that it is never easy to work cohesively. These different spheres ‘then behave in accordance with a neurotic orientation creating the challenges and tensions in the way they work together’ (Bhabha, 1984).

Your task

Using the Padlet activity ‘Navigating the tensions and challenges as Third Space Practitioners’, share some of your thoughts and experiences of the challenges you have faced as a third space practitioner.

Expectations and assumptions

Video transcript

Just before the 2020 pandemic, two of my third space practitioner colleagues and I started autoethnographic research about assumptions pertaining to the role that we held and how that had an impact on the work that we did in the third space. This research has been accepted for print in the form of a journal article and we are working on the paper now. What brought about this research was the fact that we realised we are not always talking about the same thing when we talk about templates, or unit build, or terms like chunking or curriculum development. One of my colleagues came from a teaching background and the other came from an information systems background, and I am from a cultural studies and theatre studies background. Our exposure to learning design work has been varied.

I have worked on several learning management systems, but it is not my forte. I like working on curriculum development and that too from a holistic point of view. I love conducting high-level mapping meetings and doing audits to facilitate whole-of-course approaches. My colleagues in the research team like to work on assessment design and improving the learning design on the learning management system. And we realised that we all thought of different things during team meetings even as we nodded away to indicate our understanding of who was going to do what and so on. All of us had the assumption that we were working from the same page at the same level. But when we came together, we were unpleasantly surprised to discover that we had misunderstood our understanding of common terms such as templates, or unit content, or constructive alignment for that matter. We started to see that we had gaps in our understanding of what we were meant to do owing to this assumption that we all did the same thing in a very similar manner. That led to us having frank conversations about what we actually thought we knew about each other’s work and what we thought discipline academics thought of our work. This started a great research project which is hopefully going to come to fruition very soon.

Much of the tensions and challenges experienced by third space practitioners occur because of the boundless nature of their roles. The fact that they do not sit within an easily recognised function in the higher education landscape creates a lack of a sense of belonging. This lack of a sense of belonging and displaced boundaries cause constant challenges to navigate in terms of understanding who they are in the workplace, the impact of their role and the work they do, thereby affecting their professional identity.

There are two sides to this notion of assumptions causing the lack of a sense of belonging and adding to the tensions and challenges of being a third space practitioner. One is the assumptions that other colleagues, both discipline-based academics and professional staff, make about the roles of third space practitioners. For example, we have established that discipline-based academics are not always receptive to ideas about teaching and learning advice or support given by third space practitioners. This could be due to a lack of knowledge about the roles third space practitioners perform and/or just an aversion to ideas suggested by people outside the sphere of their professional/industry knowledge. Their expectation of third space practitioners is someone who is technologically savvy; someone who will upload their teaching content into the learning management system and set up their assessment submission pages and discussion areas. This is the type of administrative support teaching academics need to make their work easier. They do not perceive third space practitioners to be a support to aspects relating to teaching and learning pedagogies, strategies and frameworks.

The other assumption that causes tensions and challenges is the perception held by third space practitioners about other third space practitioners’ skills and knowledge. As stated by Manathunga (2007) and Manoharan (2020), we come from different roles outside the discipline we work in, and we are not all trained in the same way. However, owing to similar titles and roles, it is easy for third space practitioners to assume that there will be similarities in work style, management of time, meeting delivery timelines and so on. However, in many cases, there will be instances where learning designers join a team of third space practitioners with varied skill sets and experiences but are expected to work like the rest of the team. These unspoken expectations and assumptions can be the cause of much tension and misunderstanding among third space practitioners themselves, and also strengthen misconceptions held by discipline-based staff members about the work third space practitioners do.

Assumptions of third space practitioners regarding their role is a great contributing factor to internal tension and confusion. Many a time, for the third space practitioner, be they learning designers or educational developers or third space academics, it is imperative that their voice is heard during learning design or the scoping of teaching and learning projects. They assume that their voice will be taken seriously. However, in many real-life scenarios, this assumption is not met by people they work with. Discipline-based academics can hold preconceived ideas about how they will be working on a project. They often want their voice to be registered as a teaching and learning specialist or expert. For example, they may know ways to enhance engagement of students and motivate self-regulated learning.

Case study

Andrew is a subject matter expert in the School of Business. He attends the first scoping meeting with the learning design team in his faculty. At the meeting, Sarah, who is a learning designer, asks him about the support that he needs from the learning design team. Andrew replies that he wants Sarah to make the PowerPoint slides look nicer. Sarah asks him what he means by ‘nicer’. Andrew replies that he inherited his teaching slides and that they are just too fancy, there are bits about the way the content appears that he doesn’t understand, and that he wants them to look less boring. Sarah takes notes that he wants transitions removed, information on slide to be updated and icons and graphics to be reviewed. Sarah asks if he has had time to review the content within the slides and if he wants to move some of the content in his deck of 71 slides per week to the LMS, for example. Andrew stares blankly and states that he has not been given time to review the slides or the content. All he wants are presentable teaching materials.

As a learning designer, what sort of support and advice can Sarah provide to Andrew? Use the Padlet activity ‘Navigating the tensions and challenges as Third Space Practitioners’, to share your thoughts.

Role clarity of third space practitioners

Many institutions are still not clear about the role third space practitioners play. For example, many third space practitioners will have similar job titles across the university but do very different work depending on a few factors such as:

- who they work with

- which faculty they work with

- their existing workload

- the team they are part of, whether they are with a central team or within a faculty, and last but not least

- which project they are part of.

It can be really frustrating to see this sort of disparity and to be able to do nothing about it as some of these factors are beyond the control of the third space practitioners.

For some third space practitioners, the lack of role clarity can cause tensions. There will be this constant battle about how much of the work they must do and where they draw a line before they have stepped into the work area of either a professional or an academic. For example, academics may only expect learning designers to add a few visual elements to their teaching content without having to go into detail about the purpose of adding the elements. They may not have considered the cognitive load or universal learning design aspects of being inclusive and presenting accessible materials. And there will be a few academics who are not keen to involve third space practitioners in the design or development of assessment, simply because they do not view them as being subject matter experts. These barriers cause tensions in the work third space practitioners do. One way to navigate this sense of frustration is to understand what is causing some of these tensions.

The third space professional and third space academic divide

Video transcript

I recall an instance where I was working in a team of four third space practitioners: two third space academics and two third space professionals. We had had several discussions among ourselves about our roles. Apart from the contribution made by third space academics to research, there were no clear indicators as to what distinguished the role of the third space academics from that of the professionals. As a third space academic, I often lead in unit redevelopment projects and take on the role of academic lead. The expectation is that I manage the project in terms of timelines, academic correspondence, meetings, content delivery, liaising with a third party for multimedia creation and delivery, and overall quality assurance of the project. However, in my absence, the third space professionals who do the learning design part of the work in the project can also do all these functions.

Given that we worked on several projects at a time, we sometimes crossed over into the territory of one another, and sometimes I had to work on developing content into the learning management system as well. So, the boundaries were blurred. And that led to many frank conversations as to what the value-add of our presence would be for each project. I looked across other faculties and central teams within the university for some form of role clarity regarding third space academics and I realised that the role can never be the same for all. The way we work on projects really depends on the project, the discipline, the timing, and the intended outcome of the project. Not one learning and teaching team functioned the same way across the university. And this lack of clarity in the role can cause a lot of internal and external tensions for all third space practitioners involved. I have at many times wondered why my colleagues in other faculties had more academic freedom or why they had more university-wide exposure to projects. I haven’t found the answers.

The role clarity and the recognition of third space practitioners must come from the institution for a start. When the higher education institution makes the objectives and role clarity associated with third space practitioners clear to the university, for both academic and professional roles, it becomes easier to navigate the tensions and challenges that exist in these roles. In certain universities, teaching teams comprise discipline-based academics and third space practitioners. In that case, it is clear who does what and who oversees what and they work towards a common goal of delivering purposeful teaching and learning practices.

Conclusion

Video transcript

I have often been asked if I would move out of being a third space academic. I am not sure, to be frank. There are always times that make me want to leave this role and go to a more research-focused role. In that way, I can get papers published and at least see a promotion in my lifetime as an academic. However, the team in which I work is really good. I have developed lots of good relationships in the faculties that I have worked in, and I can learn constantly in this role. There is always something I pick up in terms of tech expertise, or teaching and learning practice, or a current innovative assessment project and so on. And I have learnt to navigate my tensions and challenges. I am still navigating them, but I think I have learnt to accept my role’s limitations and growth. So the short answer to the question is that I really don’t know.

The aim of this chapter was to highlight that the role of third space practitioners – both academics and professionals – is not an easy ride, just like other roles in the higher education landscape. There are many factors contributing to the displacement that practitioners in the third space might experience and endure. However, not all is gloom and doom. Understanding that this role is in a liminal space, and that it will take time for perceptions, assumptions and role clarities to be worked out, will make working in this role a very rewarding experience and possibly create a much-needed sense of belonging.

Takeaway activity

Position description for Learning Designer in higher education

About the role

Join our Teaching and Learning Innovation team to transform education through digital assessment innovation! Shape modern pedagogy and assessments across the University. Leverage your pedagogical insights and learning design background to lead the transformation of assessment practices. Be a driving force in shaping the future of learning!

Your responsibilities will include:

– providing expertise on assessment improvements. Collaborating with staff to create evidence-based, engaging assessments that enhance student learning.

– advising on assessment design process, including iterative templates and learning modules.

– collaborating with the digital exams team, advising on assessment and exam design with teaching staff.

– creating and maintaining support resources, workshops, and training for implementing assessment solutions. Developing digital assessment expertise University wide.

Who we are looking for:

Seeking an organised, detail-focused learning designer with a strong work ethic, openness to innovation, and adept problem-solving in tight schedules. Utilise exceptional stakeholder management and interpersonal skills to collaborate with diverse stakeholders for successful outcomes. Flourish in team settings, offering guidance amidst dynamic priorities.

You will also have:

Postgraduate qualification with relevant experience or an equivalent combination of relevant experience and/or education/training.

Proven expertise in applying education theories, design principles, and modern assessment techniques to create exceptional learning experiences and activities.

Skilled in translating stakeholder needs into educational resources using enterprise technologies like LMS, ensuring an optimal student experience, seamless journey, and accessibility considerations.

Proven track record in creating online or in-person professional development, guiding the use of digital technologies, assessments, and learning design within subjects.

Example of a job advertisement that was once advertised on Seek.com in 2023

Position description for a Lecturer role in Teaching and Learning

Support and provide advice to academic staff on teaching and learning matters across the University by applying an evidence-based approach. Contribute to enhancing the quality of student learning experiences and outcomes. Provide specialist hands-on support for curriculum and learning design, produce teaching and learning resources, and work with teaching teams to improve teaching practice. Contribute to the planning, development, implementation and evaluation of programs and initiatives enabling innovation and excellence in educational practices.

Responsibilities

Education and employability

- Provide advice, support, academic leadership, and capability building in all aspects of teaching and learning in higher education, particularly in learning design and assessment.

- Apply an evidence-based approach to support and advise academics to enhance the quality of student learning experiences and outcomes.

- Work positively and effectively with Faculty colleagues and Deakin Learning Futures team members to support unit and course enhancement across the University.

- Develop and maintain an in-depth understanding of educational issues, educational methodologies and technology issues facing higher education and work with Faculty staff to develop tailored educational design solutions accordingly.

- Research, publish and present individually, or in collaboration with peers at conferences and through scholarly publication.

Selection

Qualifications and experience

- PhD in a relevant discipline and/or other relevant qualifications and experience

- Evidence of excellence in contribution to innovative teaching at undergraduate and/or postgraduate levels, in online, campus based and blended learning environments.

- Emerging reputation in research and scholarship through publications and/or exhibitions and/or success in obtaining external research funding.

- Evidence of experience in providing effective and practical support and advice to academics in relation to matters pertaining to enhancing learning, teaching and assessment.

- Evidence of ability to establish and maintain effective and collaborative working relationships with students and colleagues.

- Excellent interpersonal skills and a proven ability to undertake capability building in a collaborative and consultative manner.

Example of a Lecturer, Learning Futures Position Description – Deakin University, 2021

Your task

The first sample is a job advertisement for a third space professional. The second sample is a position description for a third space academic. Identify the areas in which these jobs in the higher education landscape intersect in terms of similar responsibilities. What are the key differences? Use the Padlet activity ‘Navigating the tensions and challenges as Third Space Practitioners’, to share your thoughts.

References

Bhabha, H. (1984). Of mimicry and man: The ambivalence of colonial discourse. October, 28, 125-133. https://doi.org/10.2307/778467

Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The location of culture. Routledge.

Boyer, E. L. (1990). Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate (ED326149). ERIC. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ed326149

Dowd, K. O., & Kaplan, D. M. (2005). The career life of academics: Boundaried or boundaryless? Human Relations, 58(6), 699.

Heggart, K., & Dickson-Deane, C. (2022). What should learning designers learn? Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 34(2), 281-296. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-021-09286-y

Manathunga, C. (2007). “Unhomely” academic developer identities: More post-colonial explorations. International Journal for Academic Development, 12(1), 25-34. https//doi:10.1080/13601440701217287

Manoharan, A. (2020). Creating connections: Polymathy and the value of third space professionals in higher education. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 24(2), 56-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603108.2019.1698475

Smith, C., Holden, M., Yu, E., & Hanlon, P. (2021). ‘So what do you do?’: Third space professionals navigating a Canadian university context. Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management, 43(5), 505-519. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2021.1884513

Veles, N., Carter, M.-A., & Boon, H. (2019). Complex collaboration champions: University third space professionals working together across borders. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 23(2-3), 75-85. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603108.2018.1428694

Whitchurch, C. (2008). Shifting identities and blurring boundaries: The emergence of third space professionals in UK higher education. Higher Education Quarterly, 62(4), 377-396. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2008.00387.x