2 Making socially just pedagogy a reality

Keith Heggart and Camille Dickson-Deane

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Kae Novak in developing this chapter.

The following chapter is a development of ideas presented in the post by Heggart, K., Dickson-Deane, C. & Novak, K. (2020, September 7). The path towards a socially just learning design. The Society of Research in Higher Education Blog. Retrieved September 12, 2020, from https://srheblog.com/2020/09/07/the-path-towards-a-socially-just-learning-design/. We as authors see this as an ongoing project.

Introduction

Being socially just has different connotations and meanings for every individual and institution. Higher education institutions, which often have as part of their mission the promotion of social good, are required to consider their own systems and practices and how they intersect with social justice, while at the same time they struggle with residual challenges from the pandemic. These challenges include ongoing questions about how universities are funded, precarious employment within those universities, and a student demographic that is increasingly demanding – and increasing diverse. Amidst these challenges, universities are also required (by government and industry) to demonstrate their connection to the workforce, and by other parts of society to commit to widening pathways to participation, especially from groups that have previously been marginalised and prevented from attending higher education.

Perhaps heightened by the growing awareness of educational injustices in the past (especially in the form of exclusion, marginalisation and systemic oppression), there have been calls for educational practice to adapt so that it is more inclusive (Bradley et al., 2008; Collins et al., 2019). This path has by no means been straightforward: arguments in the United States and even in Australia about the place of Critical Race Theory and its relevance to higher education are one example of the challenges faced by those who advocate for greater inclusivity (Bargallie & Lentin, 2022; Morgan, 2022). Nevertheless, many universities have made significant strides and implemented programs that are intended to make universities, and learning within them, more accessible and inclusive. In some cases, this focuses on entry into university (Devlin et al., 2023). Another element is to ensure that students feel like they belong at university and are therefore less likely to drop out (Mahoney et al., 2022). These initiatives are often branded as a commitment to social justice, but that term suffers from a frustrating vagueness.

This chapter works towards resolving that vagueness by bringing some clarity to the discussion around social justice within higher education. Specifically, it is an attempt to explore what that term might look like within educational practice, and specifically within the design of learning ecosystems at the tertiary level. In doing so, it is important to distinguish between teaching about social justice and socially just pedagogy. Both are important within educational settings, but there is a difference: teaching about social justice refers to content and learning activities related to equality, equity and similar topics. Socially just pedagogy, however, refers to the practice of education; that is, the principles that inform pedagogy, which ensure that the context, including tools, techniques, mindsets and behaviour, include elements such as fairness, equity, equality and inclusivity as major contributors to a holistic ecosystem that embodies diverse beings – students of the world.

This chapter examines just one aspect of that educational ecosystem: the design of learning. Learning and instructional design is still considered a developing field, even though it has been in existence for more than a century (Reiser, 2001). As recognition of the field continues to grow, learning designers are increasingly required to ensure that their designs meet both legal and institutional requirements. This is often captured under the broad umbrella of the term accessibility, whereby learning designers need to be mindful about features like font types and size, contrast, the availability of transcripts and interactive elements. However, this is a necessary but not sufficient part of socially just pedagogy. In addition to a focus on accessibility, there is a need to examine inclusivity – how it is actioned and what it means to those who experience it. This is in keeping with recent work that considers inclusivity as a rightful presence within courses (Calabrese Barton & Tan, 2020). This chapter seeks to identify ways in which learning designers can do just that. In doing so, it builds upon previous work by the authors in this field (Heggart et al., 2020).

Socially just pedagogy

Learning design, and imply by association that learning designers are becoming an integral part of the Australian higher education landscape (Heggart & Dickson-Deane, 2022). This is apparent in the increasing numbers of courses that seek to train individuals to become learning designers, as well as the numbers of advertisements for learning designers (Heggart & Dickson-Deane, 2022). Learning designers and those in similarly situated spaces are expected to liaise with academics to ensure that course materials are accessible to all students. This is becoming more important as many university courses make use of educational technologies to offer learning opportunities in different modalities. To be able to use and learn in such environments (Dickson-Deane & Chen, 2018), makes accessibility a key factor but it is not the only factor that should be considered. While it is vital that, for example, students with vision impairment can engage with course material, it is also vital that these students be seamlessly included in the learning ecosystem whilst at the same time accommodating students from differing characteristics. This is often overlooked despite calls for the decolonisation of curriculum (Tuitt et al., 2023). As the cohort of higher education students becomes increasingly diverse, there is a need to ensure that the curriculum, its content and, indeed, the entire learning ecosystem, reflects the target audience.

Achieving this can be difficult as the field commercialises core learning design processes (Traxler, 2018) At first glance, balancing time to delivery, costs and implementation with the ongoing worldly challenges is difficult for all institutions. Thus, we ask: how can learning designers cater for all the different characteristics and needs within a student cohort? This may lead to a focus on one group over another (for example a focus on accessibility via captions but ignoring inclusivity of students from diverse backgrounds) to meet institutional requirements, and it also ignores the compounding challenges presented by the intersectional nature of disadvantage (Heggart et al., 2020).

Nancy Fraser (2007) has suggested that there are ways in which this might be done. In her view, the answer lies in providing more opportunities for students to take an active part in the development of the course, rather than the learning designer and/or academic seeking to cover every eventuality. To do this, Fraser (2007) proposed three principles that could inform the design of learning experiences. The first is redistribution. This principle is about economics and in educational terms it seeks to ensure that more people have access to education (and in this case, higher education) through varying allocations – designs. Simply by increasing the opportunities for access for diverse groups of society, including those that have previously been marginalised, higher education will become more socially just. This is something that many universities are already taking seriously, via various programs and policies. Such programs are often implemented at a level beyond the remit of the individual learning designer and hence this principle will not be discussed at length in this chapter.

The second principle, however, is very much within the domain of learning designers. This is the principle of recognition. This principle encourages designers to reconsider the content of higher education, with a view to making it more diverse and representative. Pedagogical approaches that have adopted this idea include culturally relevant (Ladson-Billings, 2021) and culturally sustaining (Alim & Paris, 2017) pedagogies. There have been significant strides made in this area over recent years, with efforts to decolonise the curriculum (for an example, see Zembylas, 2018) and to include scholars who are women or gender diverse, from the Global South, or from non-dominant cultures.

The final principle espoused by Fraser is representation. This principle is perhaps the hardest to realise, even if it is the most important. Representation is best described as politically developing authentic partnerships between students and teachers in the decision-making process (Casey et al., 2022). Representation can invite learning designers to consider students less as objects, and more as active participants in the learning ecosystem, who might take a more active role in determining the what and the how of that experience – a shared design and ultimately a learning ecosystem. In doing so, it requires academics and learning designers to relinquish, in part, their control over the learning ecosystem, and instead embrace the complex and ‘messy’ nature of student-centred learning.

Clare Hocking (2010, p. 2) argues that a truly socially just education is one that ‘embraces a wide range of differences and explores their effects on individual learning’ – basically a positive acknowledgement of individual differences (Cronbach & Snow, 1969; Heggart et al., 2020; Jonassen & Grabowski, 1993). Hocking proposes that the relationships between participants be fair and just, measured by choice, distribution, opportunities, privileges, and indeed, any form of activity (Boyles et al., 2009) .

Adopting these principals signals a more in-depth approach to pedagogical activities. In the past, many attempts at inclusivity or accessibility have necessitated a focus on a particular group or learning requirement. In some cases, especially around accessibility, this will continue to be important. However, a truly socially just pedagogy requires a shift in attention away from the group or individual, to the learning ecosystem as a whole. In other words, through a careful understanding of what comprises learning ecosystems, it should be possible to incorporate the principles of redistribution, recognition and representation for all. The term learning ecosystem (Huijser et al., 2022) is used deliberately here to mark a difference between it and the more commonly used term ‘teaching and learning’. This is important because a student’s experience incorporates much more than just the ‘in-class’ time, and learning designers should be mindful of that.

The question of educational technology

While these principles are important, even more important is the practice of how these might be implemented within learning ecosystems. This is where the challenge lies: after all, what does redistribution or recognition actually look like, in Chemistry, or Accounting, or Law? And how might these principles be implemented effectively, considering the challenges involved in changing academic practice, and the limited time and budgets available to many universities?

Educational technology may answer some of these questions, especially when it is considered in conjunction with the ideas of universal design, and especially Universal Design for Learning (UDL). The usual caveats apply when it comes to educational technology: the field is littered with disappointing applications and unfulfilled promises, and this must be kept in mind in the context of developing a socially just pedagogical framework (Watters, 2023). Attention must be paid to specific learning goals, rather than the tools themselves (de Alvarez & Dickson-Deane, 2018; Dickson-Deane & Asino, 2018; Watters, 2023) – using needs to frame behaviour (Dickson-Deane & Edwards, 2021).

As described above, shifting the focus away from the student towards the learning ecosystem is something that is central to UDL (Meyer et al., 2014). Indeed, the broader universal design movement calls for a change from an individual deficit model (i.e., there is something wrong or missing with a person) towards a recognition that the deficit or problem is a societal one – which is where the problem should be addressed. It is this line of thought that has led to accessible buildings, for example. However, what does that look like in the learning context? In short, it means that, once a student has enrolled in a course or program, the learning ecosystem should be relevant to them (Dickson-Deane, 2023). For example, a student from a low socio-economic background should not face barriers due to their status, such as required access to paid content. Instead, the course should be adaptable so that these ‘deficits’ are not an imposition. Some examples might help to illustrate this point. One of the key principles of UDL is that the alterations to learning design are essential for some students, but they are of benefit for many, if not all (Fornauf & Erickson, 2020). Students with hearing impairments might require captions or transcripts on video content. Yet captions are also useful for students with no hearing difficulties or students for whom the language used to teach is not their first language. Furthermore, this is an accommodation where those who prefer to watch course materials while traveling, and do not want to disturb those around them, can prosper. This principle of multiple means of representation thus has value far beyond the students who might expressly need it.

A second principle of UDL focuses on providing multiple means of engagement for all learners. This is potentially a powerful tool, and aligns well with Fraser’s ideas of representation, in that engagement between learners and educators suggests the start of a partnership. Yet, such opportunities for engagement are often limited. This is understandable as many academics and learning designers are dealing with tight timelines and institutional inertia, and as such the learning environments may not be conducive to experimentation. In this case, interaction might be limited to some form of asynchronous activity. There is nothing wrong with asynchronous forms of interaction in and of themselves, and they definitely have a place in a course or program. However, they fail to recognise that many students, especially those entering higher education, have grown up in a world where the formalised environment is being merged with the societal environment (informal learning spaces) whereby online and interaction means something very different to them (Bennett, 2008). Students are expecting to be able to have some ownership over the course material, and to be able to adjust the content (Dickson-Deane et al., 2023). In order to leverage this predilection, learning designers can make use of David Wiley’s (2014) 5 Rs of open educational infrastructure (Table 1). These 5 Rs provide clear guidance for how learners might interact with the course material in new and interesting ways. Clearly, the ideas of remixing and redistributing, to name a few examples, go far beyond online discussion boards and opinion polls.

|

R |

Explanation |

|

Retain material |

make, own and control a copy of the resource (e.g., download and keep your own copy) |

|

Revise material |

edit, adapt and modify your copy of the resource (e.g., translate into another language) |

|

Remix material |

combine an original or revised copy of the resource with other existing material to create something new (e.g., make a mashup) |

|

Reuse material |

use your original, revised or remixed copy of the resource publicly (e.g., on a website, in a presentation, in a class) |

|

Redistribute material |

share copies of your original, revised or remixed copy of the resource with others (e.g., post a copy online or give one to a friend) |

Table 1: David Wiley’s 5Rs (Wiley, 2014)

Text-based version of Table 1

This table lists the 5Rs that define the principles of open content according to David Wiley. Each R is paired with a brief description of the rights it encompasses, emphasising the freedoms provided to users regarding open educational resources.

The 5Rs are not without significant challenges to the current higher education ecosystem. Principally, there are questions about ownership and intellectual copyright that need to be carefully negotiated, as well as issues of trust, control and management. It might prove to be confronting for academics to be expected to give permission for their course content to be remixed and distributed by students, for example. Such cases will need to be carefully considered. Nevertheless, we would propose that this shift in the locus of control is part of a wider movement in higher education, where courses are becoming less the domain of an individual course or subject coordinator and instead the product of a group of individuals, which includes academics, learning designers, analysts, media producers and so on. There are two further possible extensions of this idea of openness. Firstly, the development of a course could be made dynamic – that is, ongoing for the duration of the course – as it responds to changing ideas and discussions within the cohort. Secondly, the learners could be included as partners within the design and development of the course.

Putting it all together: Developing iterations

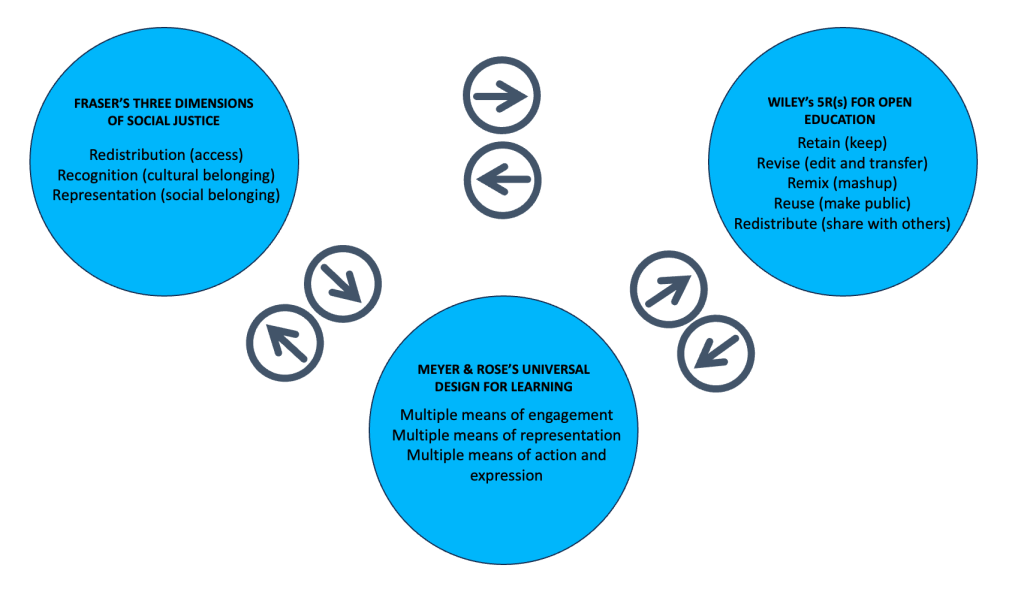

Taken together, the three concepts (Fraser’s 3Rs, Wiley's 5Rs and UDL) described above provide learning designers with a framework to use in their work to ensure that they are designing socially just learning ecosystems. There is significant overlap between some of the ideas. For example, allowing students to demonstrate their learning via multiple means of expression has something in common with the notion of remixing course material by students. Equally, there is a connection between recognising diverse learners (from Fraser’s three dimensions of social justice) and multiple means of representation. And, of course, by allowing students to reuse and redistribute course materials, students are becoming partners in the learning process and thus are more likely to be represented (although this is not an automatic process and needs to be carefully designed for and resourced if it is to occur). These connections are depicted in Figure 1.

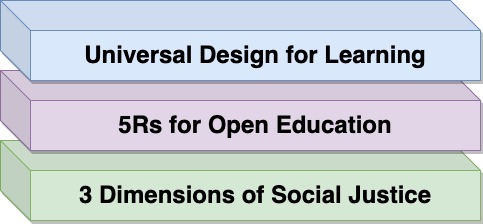

Figure 1 shows the original conception of a framework for socially just learning design (Heggart et al., 2020). It captures the connections between the different elements discussed above. However, it fails to fully articulate the nature of the relationships between the different elements, and specifically the ways in which they influence one another. The more carefully theorised depiction (Figure 2) has been developed by the authors to address this and explains the more complex relationship between the different elements of the framework.

In the new framework, Fraser’s three dimensions are placed at the bottom. This is because they occupy a foundational part of the described approach to designing learning ecosystems. The three principles of recognition, redistribution and representation are important, but they are aspirational and wide-ranging. They are aspirational because they describe what a socially just learning environment should look like: it should be accessible to all, and all should feel like they belong within the environment and they should be able to ‘see’ that belonging through representation. However, what Fraser’s dimensions do not do is provide advice or guidance (except in the most general terms) on how learning designers might create such an environment that does this: this is where the next two levels come into play.

Wiley’s 5Rs of Open Education provide actionable structures to re-envision what a contemporary learning ecosystem might look like. Recognising the fundamental shift in both resource availability and possible interaction that technological change has provided, Wiley describes ways in which the traditional learning ecosystem can be altered in order to make the most of it. The 5Rs of Open Education point out how the three dimensions of social justice might be realised in the classroom.

The final level of this revised framework belongs to Universal Design for Learning (UDL). A broad conception of UDL offers the best description of how to employ the 5Rs in a classroom setting – and, crucially, to what end they should be employed. This is worth some further explanation: the 5Rs themselves do not necessarily constitute an approach to socially just learning design. While not necessarily Wiley’s intention, it would be theoretically possible, for example, to redistribute or remix materials in a way that makes them less accessible than previously. More likely, however, the 5Rs can be used in such a way that they have little impact on the learning process. Clearly, this is not desirable for educators. By placing UDL at the highest layer, learning designers are prioritising the student experience over the technological affordances. In the next section, some examples of what this might look like in practice are explored, as well as how they align to the framework described above.

What it looks like in practice

Example 1: Creating a culture that values inclusivity

The use of the word culture can be unclear to many as it is typically used to reference the characteristics of an individual or group. The formalised processes used in designing for learning are not separate from who participates in the activity, and through self-reflection of those contributing to the outcome, there is positivity/success. Designers, instructors, administrators and (eventually) students need to cohesively contribute to the process of design and implementation knowing that without their individual interactions, understandings, discussions and perceived-positionalities, the process will have less successful outcomes. By always iteratively thinking of the next step of who will be contributing with what knowledge, and that the current knowledge is not all that can be shared in the space at that specific time, it basically shows that the design process is not only dynamic but a living process and is the key to developing an inclusive culture. This kind of activity is not easily portrayed. It requires boundaries to be relaxed, powers to be relinquished and reflections to act as a partial guide to how the learning design occurs. It allows for less formalisation of what is assumed to be known, leading to an iterative process whereby the cognitive power used to guide intentional designs leaves doors open for contextual interpretation and subjective value-making.

An example of what this may look like is not making conclusive design decisions but instead leaving enough wriggle room for students to explore the what-ifs in their learning process.

For example:

- asking students to contribute steps 3 and 4 of a guided activity which they believe will contribute to the learning goal

- allowing students to introduce ideas which they think are relevant to their understanding of the topic and then be assessed on that same topic

- going off script with one of the topics – loosely designing spaces to fill the gaps in student knowledge.

Each of these examples introduces unstructured designs that may leave everyone uneasy. Yet, this also creates a space for students to breathe and restate what they do understand with a new path as to where they would like to go with their knowledge. This can be seen as retracting the lifelong learning back into the formalised learning environment.

Example 2: Creating relevance by adding context to an existing OER

In order to increase representation, learning designers and other educators can encourage students to contribute to the development of course materials. One effective way of doing this could be in the form of an Open Educational Resource (OER). In this example, rather than the course materials or textbooks being sacrosanct and provided by the lecturer or subject coordinator (or worse, having to be purchased by the students), they could instead become open and ‘living’ documents that are being updated and developed by both the students and the academic staff.

For example, students in an Initial Teacher Education course (a program of study for students learning to be teachers) might find and share exemplars and resources on a particular topic, which are then curated into a resource that all students can use. The academic’s role in this case is to be a curator of the examples provided by the student, rather than a content producer. The learning designer, then, must provide the structure or mechanism that is required in order to make the sharing of resources as seamless as possible.

In more advanced iterations, students and the academic could use this platform as a mechanism to comment on the shared resources and to engage in a critical discussion of their usefulness and validity in various settings. Simple tools can be used by teachers and students to undertake this task. This approach is a powerful one; it reframes students less as consumers of pre-generated material and instead casts them as equal partners in the learning process. This meets the criterion of representation, as educators and students are now working as partners. It also allows students to retain, revise and remix the finished textbook or resource – and the fact that it is likely to be of immediate use in their practice will probably lead to higher levels of engagement.

Example 3: Adjusting rubrics to accommodate for different media

Rubrics are becoming an increasingly common aspect of assessment in many higher education institutions. While the development of rubrics is an area of expertise in and of itself, the use of rubrics can sometimes be restrictive. This is often the case in higher education, where there is (still) a preponderance of written assignments, reports and essays in assessment. Of course, this is appropriate in some settings, but it should be recognised that firstly, these assignments are not constructively aligned (Biggs, 1996) with the outcomes of the learning ecosystem, and secondly, such approaches privilege students who have more experience with those forms of assessment. Fortunately, the solution is relatively simple and involves redesigning the assessment in such a way as to allow students to submit their assessment task in multiple different forms.

For example, students in a nursing course might previously have been expected to write an essay about culturally safe approaches to nursing. This is clearly an important topic, and one that nurses should be expected to know about. However, there is no requirement for such an assessment task to have to be submitted in written form. Why shouldn’t students have the opportunity to record a video, or create an infographic, or even make a presentation? This allows students to choose a form that they think best suits their work. Incidentally, it might also address some concerns regarding academic integrity. Of course, such an approach might lead to some concerns about the rigour or validity of the assessment; an essay is not necessarily any more rigorous than a video presentation. For example, in some nursing courses, students recording assessment tasks is becoming more common as it is seen as more relevant than a written essay due to the advent of telemedicine. More recent advances in generative artificial intelligence have also troubled this area. The key to rigour doesn’t necessarily lie in the format but rather in the task itself, and the rubric that guides the students.

This example demonstrates aspects of all parts of the socially just learning design framework. Firstly, it adopts the UDL principle of multiple means of expression by allowing students to determine how best to meet the assessment task requirements instead of mandating them to demonstrate their learning in a particular fashion. This, in and of itself, is also an example of recognition: it recognises that students have different backgrounds and expertise and they should be able to make use of these to present their learning in the best possible setting. Broadly speaking, this is also an example of remixing: students are remixing the traditional assessment task into something that is more familiar to them.

Example 4: Providing more contextual choice in assessments

The final example also pertains to assessment. It is not particularly surprising that there is such a focus on assessment in terms of socially just learning design. As others have noted (Biggs, 1996), it is often the case that assessment drives the learning, regardless of whether that should be the case or not. In this example, assessments can be restructured or even entirely redesigned in order to provide more opportunity for students to contextualise their learning to the assessment task. This works especially well when students are asked to respond to a brief, or to take part in a scenario-type assessment. Normally, students are presented with a brief upon which to base their assessment task. However, such an approach can be exclusive, rather than inclusive, because the content of the brief will include elements of assumed or ‘hidden’ knowledge that not all students will be privy to, and thus students might be marginalised.

A better approach allows students to develop their own brief, tailored to their unique contexts and experiences. For example, in a Learning Design Program, students are often asked to develop a high-level learning design plan in response to a brief. In the past, the course coordinator has provided them with a generic brief based on a small enterprise seeking to train its facilitators in online learning practices. All students had to make use of the same brief. As explained above, this kind of context might be very familiar to some students in the course, especially those who have undertaken work in the corporate world. Yet, it might also be very unfamiliar to those who have come into the course from an educational background.

In order to improve this task, the students could be required to develop their own brief, based on their own experience. A generic brief could still be provided for those students who want it, but it would be far more effective in terms of engagement and motivation for students to consider a learning design problem to resolve that is directly related to their own context and experience. This approach necessitates extra work from learning designers; who must create a framework for students to draft their own briefs and provide several exemplars, but the increased engagement and likely higher quality outcomes would be a payoff for the additional work.

Again, this approach draws on the framework. Fraser’s (2007) notions of recognition and representation are both present: by changing the curriculum to one that is more inclusive, recognition is addressed; and allowing students to choose their own brief is an example of the development of an authentic partnership between educators and students. Students will have the opportunity to remix the exemplar brief to suit their own circumstances, and they will also have the chance to engage in the topic in multiple ways, by virtue of the choice element of the assessment task.

Conclusion

Designing for inclusivity is challenging but vitally important for learning designers. A learning designer’s first instinct might be to design learning materials that cater to everyone, but this is quickly revealed to be impossible. Some features of accessibility are not negotiable and need to be included in all course materials. However, in order to truly develop a feeling of inclusivity and belonging in a course, rather than focusing on individuals or specific groups, learning designers would be better placed to consider how they can incorporate students as active and authentic partners in the learning ecosystem. One way of doing this is by adopting the framework described in this chapter, which combines Fraser’s (2007) three dimensions of social justice with the principles of UDL and also with David Wiley’s (2014) 5Rs of Open Educational Practices.

References

Alim, H. S., & Paris, D. (2017). What is culturally sustaining pedagogy and why does it matter? In D. Paris & H. S. Alim (Eds.), Culturally sustaining pedagogies: Teaching and learning for justice in a changing world (pp. 1–21). Teachers College Press.

Bargallie, D., & Lentin, A. (2022). Beyond convergence and divergence: Towards a ‘both and’ approach to critical race and critical Indigenous studies in Australia. Current Sociology, 70(5), 665–681. https://doi.org/10.1177/00113921211024701

Bennett, W. L. (2008). Civic life online: Learning how digital media can engage youth. MIT Press.

Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32(3), 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138871

Boyles, D., Carusi, T., & Attick, D. (2009). Historical and critical interpretations of social justice. In W. Ayers, T. Quinn, & D. Stovall (Eds.), Handbook of social justice in education (pp. 30–42). Routledge.

Bradley, D., Noonan, P., Nugent, H., & Scales, B. (2008). Review of Australian higher education: Discussion paper. Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

Calabrese Barton, A., & Tan, E. (2020). Beyond equity as inclusion: A framework of ‘Rightful presence’ for guiding justice-oriented studies in teaching and learning. Educational Researcher, 49(6), 433–440. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X20927363

Casey, C. C., Goodsett, M., Hoover, J. K., Robertson, S., & Whitchurch, M. (2022). Open pedagogy. EdTechnica: The open encyclopedia of educational technology. https://dx.doi.org/10.59668/371.8682

Collins, A., Azmat, F., & Rentschler, R. (2019). ‘Bringing everyone on the same journey’: Revisiting inclusion in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 44(8), 1475–1487. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1450852

Cronbach, L. J., & Snow, R. E. (1969). Individual differences in learning ability as a function of instructional variables. Final report. School of Education, Stanford.

Devlin, M., Zhang, L. C., Edwards, D., Withers, G., McMillan, J., Vernon, L., & Trinidad, S. (2023). The costs of and economies of scale in supporting students from low socioeconomic status backgrounds in Australian higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 42(2), 290–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2022.2057450

Dickson-Deane, C. (2023). Learning within context [Case study]. In V. Rossi, Inclusive learning design in higher education: A practical guide to creating equitable learning experiences (pp. 207-210). Routledge.

Dickson-Deane, C., & Asino, T. I. (2018). Don’t forget, instructional design is about problem solving. EDUCAUSE Review. https://er.educause.edu/blogs/2018/3/dont-forget-instructional-design-is-about-problem-solving

Dickson-Deane, C., & Chen, H. L. O. (2018). Understanding user experience. In M. Khosrow-Pour (Ed.), Encyclopedia of information science and technology (pp. 7599–7608). IGI Global.

Dickson-Deane, C., & Edwards, M. (2021). Transcribing accounting lectures: Enhancing the pedagogical practice by acknowledging student behaviour. Journal of Accounting Education, 54, 100709.

Dickson-Deane, C., Heggart, K., & Vanderburg, R. (2023). Designing learning design pedagogy: Proactively integrating work-integrated learning to meet expectations. In M. J. Lehtonen, T. Kauppinen, & L. Sivula (Eds.), Design education across disciplines: Transformative learning experiences for the 21st century (pp. 125–142). Springer International Publishing.

Fornauf, B. S., & Erickson, J. D. (2020). Toward an inclusive pedagogy through universal design for learning in higher education: A review of the literature. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 33(2), 183–199.

Fraser, N. (2007). Reframing justice in a globalizing world. In D. Held & A. Kaya (Eds.), Global inequality: Patterns and explanations (pp. 252–272). Polity.

Heggart, K., & Dickson-Deane, C. (2022). What should learning designers learn? Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 34(2), 281–296.

Heggart, K., Dickson-Deane, C., & Novak, K. (2020, September 7). The path towards a socially just learning design. SRHE Blog. https://srheblog.com/2020/09/07/the-path-towards-a-socially-just-learning-design/

Hocking, C. (2010). Inclusive learning and teaching in higher education: A synthesis of research. Higher Education Academy.

Huijser, H., Kek, M. Y. C. A., Padró, F. F. (2022). Introduction: Student support services in an overall ecology for learning. In H. Huijser, M. Kek, & F. F. Padró (Eds.), Student support services. University Development and Administration. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3364-4_49-1

Jonassen, D. H., & Grabowski, B. (1993). Individual differences and instruction. Allen and Bacon.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2021). Culturally relevant pedagogy: Asking a different question. Teachers College Press.

Mahoney, B., Kumar, J., & Sabsabi, M. (2022). Strategies for student belonging: The nexus of policy and practice in higher education. Student Success, 13(3), 54–62. https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.2479

Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. T. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice. CAST Professional Publishing.

Morgan, H. (2022). Resisting the movement to ban critical race theory from schools. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 95(1), 35–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2021.2025023

Reiser, R. A. (2001). A history of instructional design and technology: Part I: A history of instructional media. Educational Technology Research and Development, 49(1), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02504506

Sulecio de Alvarez, M., & Dickson-Deane, C. (2018). Avoiding educational technology pitfalls for inclusion and equity. TechTrends, 62(4), 345–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-018-0270-0

Traxler, J. (2018). Distance learning – Predictions and possibilities. Education Sciences, 8(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8010035

Tuitt, F., Haynes, C., & Stewart, S. (Eds.). (2023). Race, equity, and the learning environment: The global relevance of critical and inclusive pedagogies in higher education. Routledge.

Watters, A. (2023). Teaching machines: The history of personalized learning. MIT Press.

Wiley, D. (2014). The access compromise and the 5th R. In D. Wiley (Ed.), An open education reader. https://openedreader.org/chapter/the-access-compromise-and-the-5th-r/

Zembylas, M. (2018). Decolonial possibilities in South African higher education: Reconfiguring humanising pedagogies as/with decolonising pedagogies. South African Journal of Education, 38(4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v38n4a1699

Media Attributions

- Figure 1: One-dimensional framework for socially just learning design activities

- Figure 2: Layered framework for socially just learning design activities

Accessibility focuses on ensuring that environments, services, and tools are usable by everyone, particularly students with disabilities. It involves removing barriers to participation and making sure that everyone can engage with educational materials and activities on the same basis as their peers. This includes providing resources in accessible formats, such as screen reader-compatible documents or videos with captions, to comply with legal obligations under acts like the Disability Discrimination Act 1992.

Inclusivity goes beyond providing access. It requires intentional and deliberate efforts to ensure that everyone, including students with disabilities, feels a sense of belonging at the university. Inclusivity encompasses designing resources and learning experiences from the outset in a way that considers diverse needs and perspectives. It's about creating an environment where all students feel valued and included, not just accommodated.

Nancy Fraser outlines three dimensions of social justice in her work: redistribution, recognition, and representation. These dimensions are designed to address different forms of social injustices and inequities:

Redistribution: Focuses on the economic aspect of social justice, aims to address inequalities in the distribution of resources and wealth and seeks to correct economic disparities by redistributing wealth, income, and opportunities to ensure a fairer allocation.

Recognition: Concentrates on the cultural and social aspect of social justice, addresses issues of misrecognition or cultural domination where certain groups are devalued or disrespected based on their identity (e.g., race, gender, ethnicity) and calls for the affirmation and respect of diverse identities and cultural practices to combat discrimination and promote equal respect.

Representation (or Political Justice): Pertains to the political aspect of social justice, deals with issues of political voice and participation, ensuring all individuals and groups have equal opportunities to be heard and influence decision-making processes and seeks to address political marginalisation and ensure fair representation in political institutions and public life.

Fraser argues that a comprehensive approach to social justice must consider all three dimensions, as focusing on only one can lead to incomplete or even counterproductive outcomes. Redistribution without recognition, for example, may fail to address the deeper cultural injustices that perpetuate economic inequalities, and vice versa. Similarly, without proper representation, marginalised groups may lack the political power needed to achieve both economic redistribution and cultural recognition.

The UDL Guidelines are a tool used in the implementation of Universal Design for Learning. These guidelines offer a set of concrete suggestions that can be applied to any discipline or domain to ensure that all learners can access and participate in meaningful, challenging learning opportunities.

– Retain – the right to make, own, and control copies of the content

– Reuse – the right to use the content in a wide range of ways (e.g., in a class, in a study group, on a website, in a video)

– Revise – the right to adapt, adjust, modify, or alter the content itself (e.g., translate the content into another language)

– Remix – the right to combine the original or revised content with other open content to create something new (e.g., incorporate the content into a mashup)

– Redistribute – the right to share copies of the original content, your revisions, or your remixes with others (e.g., give a copy of the content to a friend)

Open Educational Resources (OER) are learning, teaching and research materials in any format and medium that reside in the public domain or are under copyright that have been released under an open license, that permit no-cost access, re-use, re-purpose, adaptation and redistribution by others.

About the authors

Keith Heggart is the academic lead for the Graduate Certificate in Learning Design at UTS, where he developed an innovative course combining microcredentials and work-integrated learning. This course received the AECT Learning Innovation Award in 2022 and a UTS Teaching and Learning Citation. Keith’s research focuses on social justice and learning design, earning him awards such as the Best Publication from AECT and the Early Career Researcher award from ASCILITE. He has over 20 publications, including two books, and is an Apple Distinguished Educator.

Accessibility focuses on ensuring that environments, services, and tools are usable by everyone, particularly students with disabilities. It involves removing barriers to participation and making sure that everyone can engage with educational materials and activities on the same basis as their peers. This includes providing resources in accessible formats, such as screen reader-compatible documents or videos with captions, to comply with legal obligations under acts like the Disability Discrimination Act 1992.

Inclusivity goes beyond providing access. It requires intentional and deliberate efforts to ensure that everyone, including students with disabilities, feels a sense of belonging at the university. Inclusivity encompasses designing resources and learning experiences from the outset in a way that considers diverse needs and perspectives. It's about creating an environment where all students feel valued and included, not just accommodated.

Nancy Fraser outlines three dimensions of social justice in her work: redistribution, recognition, and representation. These dimensions are designed to address different forms of social injustices and inequities:

Redistribution: Focuses on the economic aspect of social justice, aims to address inequalities in the distribution of resources and wealth and seeks to correct economic disparities by redistributing wealth, income, and opportunities to ensure a fairer allocation.

Recognition: Concentrates on the cultural and social aspect of social justice, addresses issues of misrecognition or cultural domination where certain groups are devalued or disrespected based on their identity (e.g., race, gender, ethnicity) and calls for the affirmation and respect of diverse identities and cultural practices to combat discrimination and promote equal respect.

Representation (or Political Justice): Pertains to the political aspect of social justice, deals with issues of political voice and participation, ensuring all individuals and groups have equal opportunities to be heard and influence decision-making processes and seeks to address political marginalisation and ensure fair representation in political institutions and public life.

Fraser argues that a comprehensive approach to social justice must consider all three dimensions, as focusing on only one can lead to incomplete or even counterproductive outcomes. Redistribution without recognition, for example, may fail to address the deeper cultural injustices that perpetuate economic inequalities, and vice versa. Similarly, without proper representation, marginalised groups may lack the political power needed to achieve both economic redistribution and cultural recognition.

The UDL Guidelines are a tool used in the implementation of Universal Design for Learning. These guidelines offer a set of concrete suggestions that can be applied to any discipline or domain to ensure that all learners can access and participate in meaningful, challenging learning opportunities.

– Retain – the right to make, own, and control copies of the content

– Reuse – the right to use the content in a wide range of ways (e.g., in a class, in a study group, on a website, in a video)

– Revise – the right to adapt, adjust, modify, or alter the content itself (e.g., translate the content into another language)

– Remix – the right to combine the original or revised content with other open content to create something new (e.g., incorporate the content into a mashup)

– Redistribute – the right to share copies of the original content, your revisions, or your remixes with others (e.g., give a copy of the content to a friend)

Open Educational Resources (OER) are learning, teaching and research materials in any format and medium that reside in the public domain or are under copyright that have been released under an open license, that permit no-cost access, re-use, re-purpose, adaptation and redistribution by others.

name: Dr Camille Dickson-Deane

institution: University of Technology Sydney

website: https://www.uts.edu.au

Camille Dickson-Deane is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Technology Sydney and a Fulbright and OAS scholar. Her research focuses on pedagogical usability, individual differences, and contextualised online learning designs. Camille serves on the editorial boards of Educational Technology Research and Development and Internet and Higher Education, is an advisor for EdTechnica, and is an Associate Editor for the Journal of Computing in Higher Education. She also represents Australia on the EDUCAUSE Horizon Report panel of experts.

Accessibility focuses on ensuring that environments, services, and tools are usable by everyone, particularly students with disabilities. It involves removing barriers to participation and making sure that everyone can engage with educational materials and activities on the same basis as their peers. This includes providing resources in accessible formats, such as screen reader-compatible documents or videos with captions, to comply with legal obligations under acts like the Disability Discrimination Act 1992.

Inclusivity goes beyond providing access. It requires intentional and deliberate efforts to ensure that everyone, including students with disabilities, feels a sense of belonging at the university. Inclusivity encompasses designing resources and learning experiences from the outset in a way that considers diverse needs and perspectives. It's about creating an environment where all students feel valued and included, not just accommodated.

Nancy Fraser outlines three dimensions of social justice in her work: redistribution, recognition, and representation. These dimensions are designed to address different forms of social injustices and inequities:

Redistribution: Focuses on the economic aspect of social justice, aims to address inequalities in the distribution of resources and wealth and seeks to correct economic disparities by redistributing wealth, income, and opportunities to ensure a fairer allocation.

Recognition: Concentrates on the cultural and social aspect of social justice, addresses issues of misrecognition or cultural domination where certain groups are devalued or disrespected based on their identity (e.g., race, gender, ethnicity) and calls for the affirmation and respect of diverse identities and cultural practices to combat discrimination and promote equal respect.

Representation (or Political Justice): Pertains to the political aspect of social justice, deals with issues of political voice and participation, ensuring all individuals and groups have equal opportunities to be heard and influence decision-making processes and seeks to address political marginalisation and ensure fair representation in political institutions and public life.

Fraser argues that a comprehensive approach to social justice must consider all three dimensions, as focusing on only one can lead to incomplete or even counterproductive outcomes. Redistribution without recognition, for example, may fail to address the deeper cultural injustices that perpetuate economic inequalities, and vice versa. Similarly, without proper representation, marginalised groups may lack the political power needed to achieve both economic redistribution and cultural recognition.

The UDL Guidelines are a tool used in the implementation of Universal Design for Learning. These guidelines offer a set of concrete suggestions that can be applied to any discipline or domain to ensure that all learners can access and participate in meaningful, challenging learning opportunities.

– Retain – the right to make, own, and control copies of the content

– Reuse – the right to use the content in a wide range of ways (e.g., in a class, in a study group, on a website, in a video)

– Revise – the right to adapt, adjust, modify, or alter the content itself (e.g., translate the content into another language)

– Remix – the right to combine the original or revised content with other open content to create something new (e.g., incorporate the content into a mashup)

– Redistribute – the right to share copies of the original content, your revisions, or your remixes with others (e.g., give a copy of the content to a friend)

Open Educational Resources (OER) are learning, teaching and research materials in any format and medium that reside in the public domain or are under copyright that have been released under an open license, that permit no-cost access, re-use, re-purpose, adaptation and redistribution by others.