5 Indigenous-led learning design: Reimagining the teaching team

Katrina Thorpe; Shaun Bell; and Susan Page

Introduction

University graduates’ capacity to work effectively with Indigenous Australians to enhance equity has been a growing concern for more than two decades. In that time, a variety of reports have argued that university graduates can contribute to improved outcomes for Indigenous Australians but that requires the development of specific skills and knowledges to enable them to work effectively with Indigenous Australians (Behrendt et al., 2012; Bradley et al., 2008; Indigenous Higher Education Advisory Council, 2006; Universities Australia, 2011). There are similarities with universities in other colonised nations – for example, Canada (Battiste & Findlay, 2002), New Zealand (Jones, 2009) and Bolivia (Drange, 2011) – where inequity remains of concern. Concurrently, there has also been a growing need for staff to engage with Indigenous Knowledges and to develop cultural capability (Universities Australia, 2017). However, few universities in Australia have ready-made professional development resources to ensure that academic staff are prepared to teach, supervise Indigenous research or develop relevant curriculum.

In the absence of such professional development resources, in 2019, a team of scholars from the Centre for the Advancement of Indigenous Knowledges (CAIK) at the University of Technology (UTS), set out to develop a suite of microcredentials to address this significant gap. The suite of microcredentials consisted of three, 3 credit point online courses. Recognising that the learner group would be scholars from our own and other Australian universities, the CAIK team aimed to develop innovative offerings that allowed learners to progress independently and at their own pace. In this chapter we outline our approach to developing the first microcredential, Supervising Indigenous Higher Degree Research, through an innovative collaboration between a group of discipline experts working with a group of learning designers and media specialists.

The CAIK is an Aboriginal-led centre focused on teaching and research in Indigenous Studies. The curriculum development project reflected the motivations of the CAIK scholars, including the need to grow Indigenous student participation in higher degree research (Moreton-Robinson et al., 2020). The project was also supported through an institutional Postgraduate Strategic Funding Program grant, reflecting the university’s commitment to a national policy focused on technological advancement through retraining and upskilling of the workforce (Productivity Commission, 2017) and a global pressure to digitise teaching (Weitze, 2015). Supervising Indigenous Higher Degree Research curates a program that is relevant to the academic workforce, draws on the CAIK staff research strengths and contributes to social change through supporting excellence in Indigenous education.

The grant provided a modest amount of funding which facilitated the employment of an Indigenous project manager, but critically, provided access to a team of learning designers to work with the CAIK scholars on the design and development of the course. Vital to the successful development of Supervising Indigenous Higher Degree Research, was the collaborative effort of the CAIK’s discipline experts and the instructional design team. The learning design team supported the innovation the CAIK staff were so keen to embrace, by ensuring that the ‘content’ knowledge was presented in interesting and engaging ways, and the design of the online learning was conducive to student learning.

Through a reflective process, we found the success of our collaboration hinged on three key factors: trust, iterative discussion, and the combined skills of scholars and learning designers. Through this collaborative process we have reimagined the composition of a teaching team, beyond the traditional academic model. In the next section we provide a brief contextual background to Indigenous research supervision and showcase examples from the microcredential to illustrate the vital roles of each team member, illuminating the creative synergy which propelled the teaching development and inspired learning well beyond the curriculum content.

Context

Indigenous research supervision context: Supporting Indigenous higher degree research

In Australia, Indigenous research has rapidly grown into a prominently scholarly field (Moreton-Robinson, 2013; Nakata, 2007; Rigney, 1999) and internationally (Brayboy & Chin, 2018; Smith, 2012) and includes methodological, methods and ethical dimensions. There is also a growing literature related to the supervision of Indigenous research and Indigenous higher degree research (HDR) students (Barney, 2013; Moodie et al., 2018; Trudgett et al., 2016). Growing from concerns about the exploitation of Indigenous peoples and communities in research (Smith, 2012), along with sector wide concern about the intertwined problem of needing to grow the Indigenous researcher population and the lack of Indigenous supervisors or non-Indigenous supervisors of Indigenous HDR students, with the capability to supervise or undertake ethical Indigenous research (Hutchings et al., 2019), there have been increasing calls for professional development for staff (Australian Council of Learned Academies [ACOLA], 2016; Behrendt, 2012; Trudgett, 2014). Many scholars in Australian universities have limited knowledge of Indigenous research, having not engaged with Indigenous Studies as part of their own disciplinary education. Other scholars have come to Australia more recently from overseas and do not have the disciplinary, cultural or social knowledge to work effectively and ethically in this field. Developing the professional capability of non-Indigenous students and supervisors of higher degree research to ‘work with and for Indigenous peoples’ was therefore a significant ethical driver for curriculum development in this area.

The CAIK team previously delivered workshops on supervising Indigenous HDR candidates for university staff. The workshops included content such as Indigenous research methodologies and ethics, as well as best practice in supervising Indigenous graduate students and Indigenous research. We began the development of the subject imagining that we would develop our existing materials into a more efficient and potentially widely available offering.

The microcredential: Supervising Indigenous Higher Degree Research

Supervising Indigenous Higher Degree Research is a fully online asynchronous subject that runs over six weeks. It was first offered in December 2020 and in 2023 was in its sixth offering. To date, it has attracted 230 learners from 18 universities across Australia. In the first cohort, learners were primarily academics working in the humanities, social sciences and health sciences with a few from the information technology disciplines. Since this time, we have been pleased to witness academics enrolled from the full diversity of disciplines represented in Australian universities. It has been exciting to see writers, plant scientists, mechatronics engineers, architects, musicologists, astrophysicists and a gastronomy historian (to name a few) share knowledge and experience throughout the course. A number of learners recently moved to Australia for research and teaching positions and were interested in engaging with Indigenous communities but felt that Indigenous peoples and research were invisible within their workplaces. The wide interest has been particularly encouraging at a time when university funds were generally limited at the end of a few challenging years due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

We sought feedback early, frequently and often from our learners during the initial development of the microcredential, and continued this practice through subsequent course offerings, making adjustments in areas such as assessment based on learner feedback. What is most heartening is the way in which our learners have come to embrace the approaches described and modelled in the subject.

Dr Elizabeth Humphrys, one of our early learners who was interested in both supervising and Indigenous teaching and learning, shared the following:

We have growing numbers of Indigenous students at my university and in my School, so I completed the course to be better prepared if I was asked to contribute to the supervision panel of an Indigenous student in the future. The course was incredibly useful in terms of the content, and one of the best organised and designed training courses I’ve done. Despite having done methods subjects at postgraduate level, many of the ideas in the course – in particular around quantitative Indigenous methodologies – were new to me. The most significant outcomes to date have been on my undergraduate teaching and in assisting a non-Indigenous HDR student.

The course also inspired Elizabeth’s own practice:

The section of the course on Indigenous quantitative methodologies led me to enhance the ‘data lab’ weeks in our subject Global Economies, where we introduce students to the basics of locating, using and analysing statistics. Last year I developed an extra topic for students on responsible use of data using some of the ideas from the microcredential (with acknowledgment to CAIK), and Maggie Walter and Michele Suina’s 2019 paper ‘Indigenous data, indigenous methodologies and indigenous data sovereignty’. Students also read about 5D data and the CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. This year I introduced an additional tutorial case study on Indigenous employment, where students use a 5D lens to explore data gathering possibility and policy options.

Elizabeth further explains how her learning impacted on her supervisory practice:

The course was also useful in assisting one of my HDR students to plan their research methodology and apply for ethics approval. Their study on climate justice movements in part involves interviews with Indigenous activists. While this student’s co-supervisor works in Jumbunna, as a wholly non-Indigenous team I felt the course provided a better framework than I’d had previously for this supervision. The course assisted me in advising him on research design, the CARE principles, and needing to work with relevant Indigenous people during the design of the methodology and prior to submitting the ethics application.

Overall, the course was really thought provoking, and I have returned to my notes from it several times over the last couple of years.

Dr Elizabeth Humphrys, Social and Political Sciences, School of Communication, University of Technology Sydney.

The curriculum and learning design team

The course design team included the Director at that time, CAIK academic staff, a learning designer, other learning design professional staff, their senior supervisor, and was further supported by educational media technologists and producers. We also had significant contributions from many of the CAIK doctoral students. What is potentially unusual or unique about this project was how the combined academic subject matter expert team and core members of the learning design team met frequently at regular intervals over the course of more than 12 months, and how we created a relationship and workflow that generated a high degree of mutual understanding and collegial respect.

The three discipline experts and the project officer working on the project were all Aboriginal. All had expertise and experience in Indigenous Studies and Indigenous research. The Aboriginal members of the team had been working together for some time and were familiar with one another’s strengths and approaches to disciplinary theory. There were three staff members on the learning design team: a Senior Learning Designer, a Learning Designer and a Learning Technologist, all of whom were non-Indigenous. While the learning design team were experts in learning design, they had less experience in Indigenous education. The authors of this chapter include two of the academic collaborators (Thorpe and Page) and the Learning Designer (Bell) who worked most closely on the curriculum design project. As the project developed, it became clear that for both the academics and learning designers this was ‘uncharted ground’. This was the first time the academic staff had experienced such intensive learning design support in the development of teaching materials. The academics had no idea of the learner engagement that was possible in the online learning environment and the potential for this mode of delivery in developing a community of learners. The learning design collaborators had varied experience in Indigenous education and the Indigenous protocols that the academics almost reflexively brought to the project.

While the academic team had experience writing content for subjects using the Canvas Learning Management System (LMS), this was mainly for ‘flipped classroom’ learning where students engage in preparatory activities such as watching a pre-recorded lecture or engaging in set readings ready to come to class to participate in deeper discussion and structured in-class activities to enhance and consolidate learning. In designing for this microcredential, we were working towards an exciting and engaging, asynchronous, fully online learning experience, with optional ‘live and online’ Zoom seminars to supplement the learning in Canvas. The examples shared below show how the team approach led to far more ambitious outcomes.

We (the authors) analysed the conversational modes, communicative practices, and analogue and digital workflows that constituted the main forms of our team’s engagement over the course of the subject co-design in the context of scholarship of theories and practices that support quality online learning design. At the time of our co-design engagement, our learning designers were supported by research-based practices and guidelines through the UTS Model of Learning (University of Technology Sydney, 2019) that worked to maximise the presence of learning experiences that are authentic, aligned, active and social. These guidelines provided a strong foundation; however, anyone working with Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (Janke, 2021) acknowledges that there are significant complexities in the design of quality online learning (Phren et al., 2020) in relation to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, peoples, knowledges and histories. Some of our team of designers had prior experience in this domain at other institutions and had some understanding and training of practices and approaches that can better support such projects. As our further discussion highlights, such understanding or adherence to available protocol guidelines does not replicate authentic, consistent and sustained collaboration between diverse members (or stakeholders) of the academic and professional staff on the project, or the specific experience and knowledge of an Indigenous-led unit. Our reflection identified a number of practices we undertook that we argue contributed significantly to our success, including a ‘flat’ team structure, common team understandings and understanding of wider university structures. A ‘structural’ or organisational approach within the co-design team meetings that was arguably ‘flat’, enabled the sharing by multiple voices and experiences.

Flattening the hierarchy

This lack of hierarchy within the group led to sustained synchronous and asynchronous feedback discussions relating to learner experience, content design and presentation, as well as issues surrounding ‘modality’, tone and voice. These collaborative discussions were enabled by strong rapport with honest, deliberate, and kind interactions between team members. In addition, all the people who worked on the project felt a strong sense of personal and professional learning through this multiskilled and multidisciplinary engagement and academic and professional staff collaboration (Cheek, 2021; Osguthorpe, 2007). While our course design team were not aware of this at the time, the work by scholars like Osguthorpe and colleagues (2018) articulates an ethical or moral imperative in learning design, with models that enable transformative learning at all levels.

Seeking permissions and protocols

A ‘common point of understanding’ among core team members were the additional requirements around seeking permission for materials used in the module, respecting cultural and intellectual authority and ownership (Janke, 2021). Some non-Indigenous team members had some specific training and experience and understood concepts like Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property rights, and they worked with their non-Indigenous colleagues to understand the ‘stakes’ by exploring resources available through reputable protocol documents, (Australia Council for the Arts, 2019), but they could not rely on this knowledge in place of deliberate discussion with co-design partners. This checking by the non-Indigenous team members even where they had existing knowledge is a practical demonstration of cultural humility (Burgess et al., 2022; Cox & Simpson, 2020) that aims to ‘develop and maintain respectful processes and relationships based on mutual trust’ (p. 2). Non-Indigenous people acting like experts in Indigenous matters can often be abrasive for Indigenous colleagues, so ‘checking in’ is one of the elements contributing to the development of trust.

Rapport and reciprocity

It is well recognised in the literature that relationship building, rapport and reciprocity are important when working and researching with Aboriginal communities and this can take time (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, 2020; NSW Department of Community Services, 2009). Indeed, taking time and providing the appropriate resources are essential to ensuring successful outcomes; however, one of the common criticisms is that universities do not adequately accommodate this vital work (Smith et al., 2017). The broader university environment recognised our project’s unique status as an Indigenous-led project with a goal to exemplify best practice in respectful use of Indigenous cultural and intellectual property. There was a clear recognition that this approach necessitated different and specific ways of working, including a higher degree of consultation and collaboration with stakeholders including students, artists, external academics and other experts. Supportive management within faculty and the learning design unit, including learning design supervisors who were across issues related to ownership, copyright and permissions, provided support within the project to allow for practical issues like long lead-times to commence discussions with experts and figures external to the university. As we discuss below, we had support to engage media producers and design experts who actively changed their processes to ensure our efforts to enhance the presentation of content and create interactive multimedia were respectful of issues related to cultural sensitivity and appropriateness.

Enacting the curriculum development collaboration

We have discussed the way in which our team structure and institutional context might have contributed to, or enabled, a co-design partnership that has produced a quality online learning experience with an enduring impact on learners. What enabled this in practice was how institutional supports, moral/ethical investment in the work, specific experience and expertise, and interpersonal and individual capacity building all came together in the specific design of explicit ‘learning moments’ or objects within the Canvas LMS (see Figures 1 and 2 below). Our workflow built on existing co-design models and learning approaches within UTS and more broadly, and capitalised on a shared understanding of other common academic production workflows, but was most significantly enhanced by a ‘dialogic model’ exemplified by the CAIK academic team – a kind of open, collaborative, deliberative conscious discussion – as well as specific design knowledges of core team members. In practice, this often meant an ‘all in’ approach to the collaborative authoring and design of pages, as we’ve outlined.

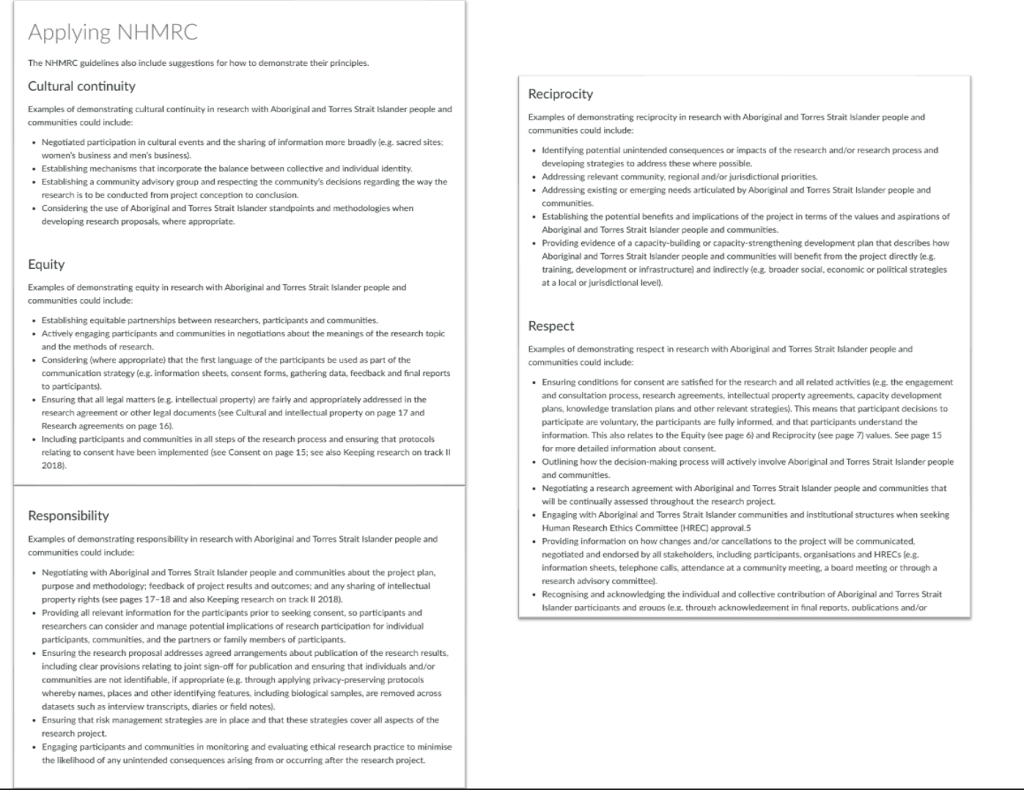

The examples below are from one of the pages within Module 2 (related to Indigenous research ethics) of the Canvas LMS subject that helps highlight three important things we learnt during this project, which are: (1) the importance of trust; (2) the value of conversation and iteration; and (3) the strength of a multidisciplinary team.

The importance of trust

The two figures below show how one page developed over time. In Canvas, you can create pages through a combination of rich-text and HTML formatting. The intuitive nature of the platform meant that the learning design team invited our academic partners to draft directly on the Canvas page, fostering opportunities for the academic staff to learn and develop digital skills in a supported environment (Huizinga et al., 2014). Through this process, the team built the trust that became a critical feature of the course development and which is so important for success in collaborative relationships (Bond-Barnard et al., 2018; Buanduchi, 2013). One of the useful features of Canvas is that it is very hard to ‘break’ something, and it has robust versioning abilities which means it is also hard to lose your work. The CAIK team took to Canvas with gusto, but that does not mean it was always easy-going. Figure 1 shows where we started in July of 2020, while Figure 2 shows a ‘final version’ of the page finalised in November. We authored this page through 20 iterations of distinct edits, involving in-page design, and many hours of online video discussion between learning designers and academics as changes were made to this single page.

We include this example for several reasons. Firstly, because the text from the NHMRC Ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and communities: Guidelines for researchers and stakeholders covers fundamental knowledge for researchers and research supervisors working in health-related disciplines, and outlines ways of thinking about ethical research guidelines more broadly. Secondly, because we collectively found the development of this page content challenging as the material covered is important, but also somewhat ‘dry’ and policy-driven. The desire to move beyond the presentation of content to learner engagement led to the pedagogical choice to use a variety of media. The ‘After’ page includes a short video, interactive elements and a reflective task, as well as a link to the original document to ensure learners could locate the document for future reference. There is ample evidence to support the improvements in student efficacy through providing opportunities for learning across multiple media modalities (Wayan, 2020), and providing learning that includes a degree of meaningful interactivity, choice, and agency (Dailey-Herbert, 2018). Those engaged in design work can easily find helpful checklists and protocols to unpack the selection of meaningful technology-enhanced interactivity.

Every learning design project has its challenges. Occasionally, these arise from a disconnect between the academic and the learning designer and team because they may have a different vision for a specific resource, a page or whole subject! We found that the only way around this was to ‘talk it out’, and a strong working relationship might be one of the ‘hidden ingredients’ in a successful course design build (Mason & Lefrere, 2003).

The value of conversation and iteration

This leads, to the second point, which is the value of iteration through ongoing conversation. This ‘teacher talk’ has been identified as important to successful design collaborations (McKenney et al., 2016). In our case, this was via weekly meetings and an agreed mode of communication in the form of colour coded notes in the pages themselves – a bit like when you collaborate on a document. This workflow was arguably also very ‘flat’ in structure: no single team member’s comments had any more or less prominence, and all comments were visible to the whole team. Everyone worked together on the pages, which resulted in a very clean and polished final presentation, but it also meant a sometimes-messy process of drafting.

We were able to work through the challenges related to the NHMRC and other pages as we’d already developed a strong and collaborative basis of trust because of our collective response to design challenge we faced earlier in the project.

Early in our design journey we found ourselves needing to down tools and talk through one such issue. Our team of multidisciplinary designers had collaborated on an interactive resource introducing learners to concepts of a ‘Welcome’ and ‘Acknowledgment of Country’, which we made using a common rich media authoring tool, using a standard production workflow. The design concept for the artefact was simple, comprising an engaging visual background with a clickable object that revealed text content set against an illustrated background depicting Australian flora – too easy, right?

We were relatively early in the co-design of this subject, and relationships between the CAIK team and the learning design team were still forming. To say our team of designers were keen to impress is an understatement – internally, we knew this project had the potential to garner attention from senior figures in other parts of our university, and our designers working across early phases of the project also had a degree of personal investment. We’d already had several conversations and had some material in draft form, but we’d yet to ‘crack’ the overarching shape of the microcredential subject.

This is fairly common when designing a new learning experience with a new group of co-designers, and as part of our design process, we aim to rapidly design, prototype and implement educational resources to ‘get us into the drafting’, with the goal of creating familiarity and comfort with the authoring tools and process, and then iterating and refining the materials once deployed. This workflow can sometimes be at odds with the ‘durations’ and timelines of the other kinds of work that make up the workloads of our main co-design partners, working academics: teaching and publishing.

In this example, the result of our different approaches led to the selection of a visual element – a design featuring a flower, the Gymea lily – that was not just inappropriate, but held important cultural meanings that the learning designers were unaware of – In this instance, we did not take the time to talk through the design, and we rushed into production, hoping to spur our new co-design partners into activity, without being conscious of how our design choice was playing out in discussions within the subject matter expert team.

What did this experience teach us?

- It is vital that learning designers work with their expert co-designers to understand the appropriateness of their learning design approach, especially when working with cultural content that carries a specific, sacred, or sensitive meaning.

- There is a wealth of protocol and guideline documents to support designers who are unsure of issues of process, or procedure. These resources will help, but trust and courtesy are arguably more important because protocols or guidelines cannot possibly provide the means to understand all situations, and should not be used in place of honest and direct conversation with co-designers. You cannot replace or replicate knowledge and mutual respect.

- It was not all bad news: this experience provided our academic co-designers their first real sense of the power of design and the ‘wow’ factor and wonder that well-designed interactive learning can create.

The value of the multidisciplinary team including learning designers, teachers and academics

The importance of conversation leads to the third point: a strong multi-disciplinary team can make all the difference in the process of designing a good learning sequence. There is now a growing body of research that highlights how differing team structures and compositions can enable design through ‘ill-structured’ or poorly understood design problems and contexts (Ertmer, 2008; Pan & Thompson, 2009; White et al., 2021). There is also a growing interest in the affordances provided by ‘third space’ education professional staff who bring their own expertise, and share common understandings or motivations around work culture and goals with academic staff (White et al., 2021).

Our project had the typical issues of overworked dedicated academic staff managing multiple competing imperatives, on top of commencing right at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and our university’s rapid transition to fully online learning. We often met online over Zoom in between many other Zoom meetings. There was also a degree of experimentation and uncertainty around the scope and ambition for the subject. We worked online, at first on documents, and then in our LMS. Most importantly, though, we engaged in a kind of relationship of mutual teaching and learning. While our learning designers had some awareness of some of the issues and concepts our microcredential subject engages with, our academic co-design partners did need to spend time to educate our learning design team so they could understand enough to be able to effectively support our goal. At the same time, our academic team were relatively unfamiliar with the affordance, possibilities and limitations of the online learning environment. Our learning design team spent time engaging in forms of design thinking, prototyping and troubleshooting to create activities, design resources and engaging presentation of knowledge, as well as developing systems to enable the smooth delivery of the completed learning experience.

This dynamic resulted in meetings focused on content creation, alongside discussions on the best ways to present and deliver this content through digital and online learning techniques. The academic team would engage in theoretical discussions in an inclusive manner with the designers, inviting us into the discussion and even considering some of the points we raised deriving from our experience as learners of this knowledge. There are ample accounts of negative dynamics between academics and learning designers, often centred around authority, positionality and our different roles and drivers related to the creation of a learning experience or product (Tay et al., 2023). It is common for learning designers in Australian higher educational settings to be employed as professional staff, although many also have teaching or academic experience, or hold relevant qualifications.

In some instances, the specific experience of our learning designers is that they often must take on the unpleasant role of managing deadlines or chasing academic co-designers for their contributions – the worst outcome being when a co-design partnership is undermined or forestalled by disengaged or oppositional team members, potentially using their authority and position in a way that invalidates more junior and precarious team members (Tay et al., 2023).This was not the case in this project where mutual respect for different competencies, skills and knowledges created a collaborative and iterative workflow that enabled the production of highly engaging and well- authored learning sequences.

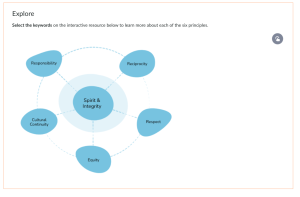

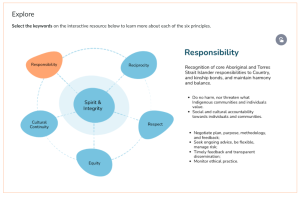

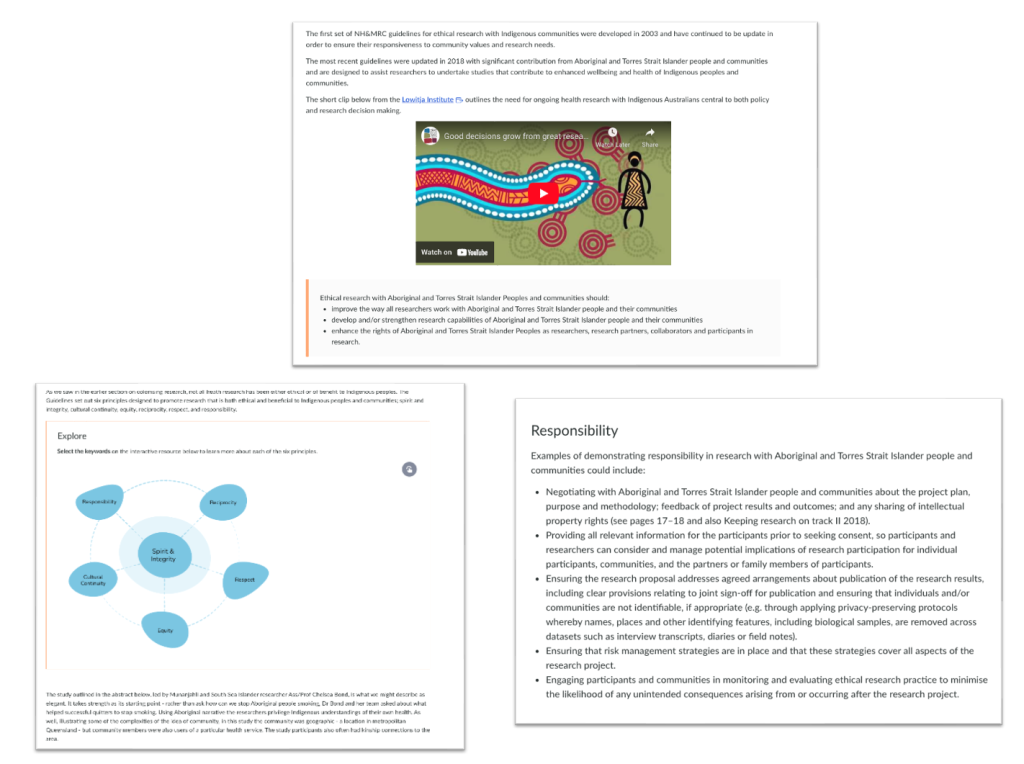

We can see this successful co-authoring in the final version of the NHMRC page introduced earlier. There are some good learning design elements on the page. For example, we present a ‘choice’ for learners by providing optional links to more information (e.g., to the NHMRC website); we also ‘chunked’ information in different formats like videos, and through the ‘explore’ interactive, which was made using a tool called genial.ly. There is also a ‘scaffolding’ activity that progressively moves students to a stronger understanding of the material through the ‘read, consider, compare’ activity using HTML layout, an H5P document tool and a Canvas social poll.

A specific example can be seen in Figure 3 below, also from the NHMRC page in Module 2. The creation of this image involved the whole team discussing issues related to content organisation, authenticity of imagery and design, and ease of access and Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) standards. Everyone on the team brought a perspective, and the result is an inviting presentation of the content.

Figure 3. ‘NHMRC interactive made using genial.ly’. Based on material provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council (representing the Commonwealth of Australia). Used with permission. All rights reserved by NHMRC.

In designing the interactive, our interactives expert found that the key was chunking the sections and deciding what knowledge was at the core of all the information in what is a very lengthy document. As for the visuals, we discussed how we already had a style guide for this specific suite of courses developed over many months, and it was important to use this consistently to keep the course site clean and matching the existing style. In our context at UTS, these style guides are typically ‘uncomplicated’ and built out from stock assets. In the specific context of our project, we required a greater deal of collaboration with Indigenous Australian artists and knowledge holders and practitioners, and as much as we could we engaged external collaborators and licensed works. This was not without complication, and required ongoing conversations with the artists to ensure we engaged in respectful repurposing of their work. In terms of the example in Figure 3, this interactive collaboration between the design team and the discipline experts led to excellent design and content – which learners found deeply engaging. Dr Natalie Morrison from Western Sydney University noted:

‘This course has been exceptional. The flow, the materials and all the presentation aspects are second to none. I will have to rethink everything I do in my teaching practices – both to reflect what I am learning here by intent (course materials) but also that which is unintentional (the delivery format).’

Dr Natalie Morrison, Senior Lecturer, School of Medicine and the Translational Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University.

Conclusion

While there has been much discussion of the digital revolution, the scramble to switch to largely online learning in Australian schools and universities at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic would suggest, at the level of the classroom at least, that there has been less a revolution and more an intermittent evolution. The need for skills development is clear (Sousa & Rocha, 2019), but that development will require trust, ongoing dialogue and, vitally, access to multidisciplinary teams. Skills development for academic staff is important; however, there are specialist skills that for the sake of efficiency and effectiveness require learning designers to be integral parts of a teaching team. There is ample opportunity to increase efficiency and effectiveness through the exploration of different design models and team structures. As our experience has shown, combining academic and professional staff members, and encouraging the co-design of subjects and enabling their co-development with support through funding models, staffing resources and time, not only enabled the creation of a unique, highly regarded and successful fully online learning experience, it also generated significant capacity for individuals and institutions who are further supporting specifically Indigenous ways of learning and teaching across the sector. Such is the strength of this collaboration that we authors have come together to document the journey and outcome of this Aboriginal-led co-design process. Alongside this, we’ve seen substantial capacity and knowledge growth of online learning approaches and methodologies in our academic and professional staff, as well as the learners who have undertaken the subject.

Acknowledgements:

As authors we would like to acknowledge the contributions of the team, whose collaborative efforts brought the microcredential to fruition.

Professor Gawaian Bodkin-Andrews played a significant role in the development of curriculum content, Dr Danièle Hromek (Project Officer) contributed to the literature review, content and early design work. PhD scholars (and now) Dr Ros Sawtell and Dr Rhonda Povey shared their experiences of navigating their PhD candidature and Artist Nathan Peckham’s artwork is featured throughout the course (with formal agreement). UTS Designers Jessy Mai, Learning Designer Eleanor Rowan, Senior Learning Designer John Vulic, Post Graduate Learning Designer (PGLD) Media Manager Anthony Bourke and PGLD Media Producer Matilda Fay enhanced the visual presentation of our ideas and transformed the academic content into interactive and engaging activities. UTS FASS Short Forms of Learning Director Sita Chopra and Short Forms of Learning Coordinator Ines Soares provided strategic advice on microcredential development, industry engagement and impact. The project was funded through the UTS Postgraduate Strategic Funding Program.

References

Australia Council for the Arts. (2019). Protocols for using First Nations cultural and intellectual property in the Arts. https://australiacouncil.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/protocols-for-using-first-nati-5f72716d09f01.pdf

Australian Council of Learned Academies. (2016). Review of Australia’s research training system: Final report. ACOLA. https://acola.org/research-training-system-review-saf13/

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. (2020). AIATSIS code of ethics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research. https://aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-10/aiatsis-code-ethics.pdf

Barney, K. (2013). ‘Taking your mob with you’: Giving voice to the experiences of Indigenous Australian postgraduate students. Higher Education Research & Development, 32(4), 515–528.

Battiste, M., Bell, L., & Findlay, L. M. (2002). Decolonizing education in Canadian universities: An interdisciplinary, international, indigenous research project. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 26(2), 82–95.

Behrendt, L. Y., Larkin, S., Griew, R., & Kelly, P. (2012). Review of higher education access and outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education. https://www.education.gov.au/download/2658/review-higher-education-access-and-outcomes-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-people/3703/document/pdf

Bond-Barnard, T. J., Fletcher, L., & Steyn, H. (2018). Linking trust and collaboration in project teams to project management success. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 11(2), 432–457.

Bradley, D., Noonan, P., Nugent, H., & Scales, B. (2008). Review of Australian higher education: Final report. https://vital.voced.edu.au/vital/access/services/Download/ngv:32134/SOURCE2

Brayboy, B. M. J., & Chin, J. (2018) A match made in heaven: Tribal critical race theory and critical indigenous research methodologies. In J. T. De Cuir-Gunby, T. K. Chapman, & P. A. Schutz (Eds.), Understanding critical race research methods and methodologies: Lessons from the field (pp. 51–63). Taylor & Francis.

Bunduchi, R. (2013). Trust, partner selection and innovation outcome in collaborative new product development. Production Planning & Control, 24(2–3), 145–157.

Burgess, C., Thorpe, K., Egan, S., & Harwood, V. (2022). Towards a conceptual framework for Country-centred teaching and learning. Teachers and Teaching, 28(8), 925–942.

Cheek, D. (2021). Analogies, metaphors, proverbs, and similes for learning. In B. Hokanson, M. sExter, A. Grincewicz, M. Schmidt, & A. A. Tawfik (Eds.), Learning: Design, engagement and definition: Interdisciplinarity and learning (pp. 87–97). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85078-4_7

Cox, J. L., & Simpson, M. D. (2020). Cultural humility: A proposed model for a continuing professional development program. Pharmacy, 8(4), 214–223.

Dailey-Hebert, A. (2018). Maximizing interactivity in online learning: Moving beyond discussion boards. Journal of Educators Online, 15(3), 1–26.

Drange, D. L. (2011). Intercultural education in the multicultural and multilingual Bolivian context. Intercultural Education, 22(1), 29–42.

Ertmer, P. A., Stepich, D. A., York, C. S., Stickman, A., Wu, X., Zurek, S., & Goktas, Y. (2008). How instructional design experts use knowledge and experience to solve ill‐structured problems. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 21(1), 17-42

Huizinga, T., Handelzalts, A., Nieveen, N., & Voogt, J. M. (2014). Teacher involvement in curriculum design: Need for support to enhance teachers’ design expertise. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 46(1), 33–57.

Hutchings, K., Bainbridge, R., Bodle, K., & Miller, A. (2019). Determinants of attraction, retention and completion for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander higher degree research students: A systematic review to inform future research directions. Research in Higher Education, 60, 245–272.

Indigenous Higher Education Advisory Council. (2006). Partnerships, pathways and policies: Improving Indigenous education outcomes. Conference report of the Second Annual Indigenous Higher Education Conference. Commonwealth of Australia. https://vital.voced.edu.au/vital/access/services/Download/ngv:17061/SOURCE2

Janke, T. (2021). True tracks: Respecting Indigenous knowledge and culture. UNSW Press.

Jones, C. (2009). Indigenous legal issues, Indigenous perspectives and Indigenous law in the New Zealand LLB curriculum. Legal Education Review, 19(1/2), 257–270.

Mason, J., & Lefrere, P. (2003). Trust, collaboration, e‐learning and organisational transformation. International Journal of Training and Development, 7(4), 259–270.

McKenney, S., Boschman, F., Pieters, J., & Voogt, J. (2016). Collaborative design of technology-enhanced learning: What can we learn from teacher talk? TechTrends, 60(4), 385–391.

Moodie, N., Ewen, S., McLeod, J., & Platania-Phung, C. (2018). Indigenous graduate research students in Australia: A critical review of the research. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(4), 805–820.

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2013). Towards an Australian Indigenous women’s standpoint theory: A methodological tool. Australian Feminist Studies, 28(78), 331–347.

Moreton-Robinson, A., Anderson, P., Blue, L., Nguyen, L., & Pham, T. (2020). Report on indigenous success in higher degree by research: Prepared for the Australian Government Department of Education and Training. Indigenous Research and Engagement Unit, Queensland University of Technology. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/199805/1/49092585.pdf

Nakata, M. (2007). The cultural interface. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 36(S1), 7–14.

NSW Department of Community Services. (2009). Working with Aboriginal people and communities: A practice resource. https://www.facs.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/322248/working_with_aboriginal_people.pdf

Osguthorpe, R. T. (2007). Instructional design in a flat world. Educational Technology, 47(2), 48–50.

Osguthorpe, R. T., Osguthorpe, R., Jacob, W. J., & Davies, R. S. (2018). The moral dimensions of instructional design. In R. E. West (Ed.), Foundations of learning and instructional design technology. EdTech Books. https://edtechbooks.org/lidtfoundations/instructional_design_moral_dimensions

Pan, C., & Thompson, K., (2009). Exploring dynamics between instructional designers and higher education faculty: An ethnographic case study. Journal of Educational Technology Development and Exchange, 2(1), 33–52.

Prehn, J., Peacock, H., Guerzoni, M. A., & Walter, M. (2020). Virtual tours of Country: Creating and embedding resource-appropriate Aboriginal pedagogy at Australian universities. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching, 3(Sp. Iss. 1), 12–20.

Productivity Commission. (2017). Upskilling and retraining, shifting the dial: 5 year productivity review: Supporting paper no. 8. Productivity Commission. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/productivity-review/report/productivity-review-supporting8.pdf

Rigney, L. I. (1999). Internationalization of an Indigenous anticolonial cultural critique of research methodologies: A guide to Indigenist research methodology and its principles. Wicazo Sa Review, 14(2), 109–121.

Smith, J. A., Larkin, S., Yibarbuk, D., & Guenther, J. (2017). What do we know about community engagement in Indigenous education contexts and how might this impact on pathways into higher education? In J. Frawley, S. Larkin, & J. A. Smith (Eds.), Indigenous pathways, transitions and participation in higher education: From policy to practice (pp. 31–44). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4062-7_3

Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). Zed Books.

Sousa, M. J., & Rocha, Á. (2019). Digital learning: Developing skills for digital transformation of organizations. Future Generation Computer Systems, 91, 327–334.

Tay, A., Huijser, H., Dart, S., & Cathcart, A. (2023). Learning technology as contested terrain: Insights from teaching academics and learning designers in Australian higher education. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 39(1), 56–70. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.8179

Trudgett, M. (2014). Supervision provided to Indigenous Australian doctoral students: A black and white issue. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(5), 1035–1048.

Trudgett, M., Page, S., & Harrison, N. (2016). Brilliant minds: A snapshot of successful Indigenous Australian doctoral students. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 45(1), 70–79.

Universities Australia. (2011). National best practice framework for Indigenous cultural competency in Australian universities. Universities Australia. https://universitiesaustralia.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/National-Best-Practice-Framework-for-Indigenous-Cultural-Competency-in-Australian-Universities.pdf

Universities Australia. (2017). Indigenous Strategy 2017–2020. Universities Australia. https://universitiesaustralia.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Indigenous-Strategy-2019.pdf

University of Technology Sydney. (n.d.). What students learn: The UTS model of learning, https://www.uts.edu.au/research-and-teaching/learning-and-teaching/uts-model-learning/what-students-learn

Wayan K. Y. (2020). Multimedia learning theory. In J. Egbert & M. Roe (Eds.), Theoretical models for teaching and research. PressBooks. https://opentext.wsu.edu/theoreticalmodelsforteachingandresearch/chapter/multimedia-learning-theory/

Weitze, C. L. (2015). Pedagogical innovation in teacher teams: An organisational learning design model for continuous competence development. In A. Jefferies & M. Cubric (Eds.), Proceedings of the 14th European Conference on e-Learning ECEL-2015 (pp. 629–638). Academic Conferences and Publishing International.

White, S., White, S., & Borthwick, K. (2021). Blended professionals, technology and online learning: Identifying a socio‐technical third space in higher education. Higher Education Quarterly, 75(1), 161–174.

Media Attributions

- NHMRC page – Before

- After

- genially interactive element

- genially interactive element – Responsibility