3 Designing inclusive learning experience through Open Educational Practices

Mais Fatayer

Introduction

I wrote this chapter to equip learning designers with both theoretical insights and practical guidance on integrating Open Educational Practices (OEP) into learning design practice. Along the chapter, I provide advice that helps learning designers understand how OEP contribute to the advancement of social justice in higher education, drawing on my experience in learning design and open education.

For higher educational institutions, OEP hold the potential to reduce educational barriers for students, thereby expanding learning opportunities and democratising education, promoting a connected academic community and enhancing student learning experience. In the field of educational technology, OEP benefit from leveraging current technologies to develop content that is both accessible and inclusive. In the learning design sphere, OEP offer innovative methods and techniques to enhance interaction and active participation in the learning process, fostering a more dynamic and collaborative approach to knowledge acquisition as an integral part of pedagogy (Paskevicius & Irvine, 2019). However, drawing from over a decade of experience in both formal and informal leadership roles as a learning designer, I have frequently observed the hesitant and fragile incorporation of OEP into daily learning design practices. These instances occur due to many barriers such as lack of awareness of the role of open education in advancing learning, concerns about the quality of Open Educational Resources (OER), time constraints for either creating or reviewing OER, lack of clarity about intellectual property issues, lack of recognition of OEP and lack of adequate infrastructure for hosting OER. Existing literature is also in alignment with of all these barriers (Atenas et al., 2022; Morgan, 2019), which highlights evidence of similar barriers from institutions around the world.

Even with the previous challenges, learning design is a significant area to advance open education in higher education. In this chapter, I reinforce the prevailing call for the involvement of learning designers in open education, as advocated by Roberts at al. (2022). Additionally, I extend this appeal by calling for intentional steps toward adopting OEP in learning design practice. The aim here is to help learning designers to seamlessly integrate OEP into their learning design practice in order to enhance student learning experiences. Further, the advice provided in this chapter offers a pathway to make OEP more visible through practical approaches so learning designers will be able to take concrete steps towards socially just education.

But why is open education important to learning designers? Why does it matter, and why should learning designers care? In response to these underlying questions, I pose three key broad responses that I’ll elaborate on throughout the chapter:

- Learning designers possess the skills to develop OER: These skills are integral in learning design practice and are deployed consistently in building educational materials.

- The open education movement in higher education is advancing slowly: Learning designers are urged to utilise their relationships and leadership skills to raise awareness and encourage greater engagement among faculties and senior management.

- Learning design is rooted in human-centred approaches: As learning designers, our core commitment is to design for the betterment of people to enable socially just education. This ethical responsibility aligns strongly with the values of open education.

As a final note, over the past two decades the open education movement has made substantial advances in various parts of the world, notably in the United States and Canada. While Australia has been perceived as a late adopter, it has increasingly begun to make significant contributions to the field, signaling a promising emergence in open education initiatives. Throughout the chapter, I will be borrowing examples from existing projects and initiatives in Australia and globally to illustrate the growing impact of OEP on higher education in different places.

Understanding Open Educational Practices (OEP)

This section offers a concise chronological exploration of key concepts in open education. It begins with a historical overview of open education and open pedagogy, encompassing contemporary perspectives, and concludes with an exploration of Open Educational Practices (OEP). The section concludes with highlighting the role of open education as a catalyst for social justice.

Before delving into OEP, it is vital to highlight the more general concept of open education. As a pedagogical approach, open education advocates for increased participation, democracy, and social inclusion within the educational sphere. Lambert (2018, p. 239) introduced a conceptualisation of open education wherein social justice stands as its overarching objective:

“Open Education is the development of free digitally enabled learning materials and experiences primarily by and for the benefit and empowerment of non-privileged learners who may be under-represented in education systems or marginalised in their global context. Success of social justice aligned programs can be measured not by any particular technical feature or format, but instead by the extent to which they enact redistributive justice, recognitive justice and/or representational justice.”

For learning designers who are usually immersed in the design process (i.e., co-creation, constructive alignment between content and outcomes, developing inclusive and accessible material, etc), this definition holds significance for two key reasons. Firstly, it transitions the perspective of open education from being perceived merely as a collection of pedagogies applicable to all learners, to encompassing both processes and artefacts tailored for and co-created with marginalised learners. Secondly, it establishes a quality assurance mechanism, ensuring that both the process and artefacts are responsive to the existing needs of the learners involved.

The evolution of open education has unfolded gradually, shaped by various influences and developments over time. The historical timeline of open education spans decades, from the introduction of the Open University in the 1960s (Open University, 2010), as an advocate for openness and socially just education, to the early mention of open education in the 1970s by Elliot (1973) and Mai (1978), describing tensions between ‘closed’ and ‘open’ pedagogies. In 1998 David Wiley coined the term ‘open content’ working on the premise that educational content should be developed and shared freely and openly similar to the free software philosophy (DiBiase, 2011). Moving into the 21st century, the emergence of Web 2.0 technologies contributed significantly to the rise of OER. In 2001, the OpenCourseWare of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) marked a milestone, when MIT academics made course materials freely available online. This was followed by the introduction of Creative Commons licenses in 2001, enabling legal sharing and remixing of content.

Following the efforts of MIT and Creative Commons, in 2002 the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the Western Cooperative for Educational Telecommunications, and global education leaders met at UNESCO headquarters for the OER Forum. The group explored the impact of open courseware in higher education and concluded with a declaration

‘At the conclusion of the Forum on the Impact of Open Courseware for Higher Education in Developing Countries, organized by UNESCO, the participants express their satisfaction and their wish to develop together a universal educational resource available for the whole of humanity, to be referred to henceforth as Open Educational Resources.’ (UNESCO, 2002, p. 28)

This forum represents a significant milestone in the open education movement’s journey. Additionally, international organisations, including UNESCO, OECD, and ICDE, played a significant role in initiatives such as ‘open educational quality initiatives’ (OPAL) to promote OER adoption globally (Falconer et al., 2013). Since that time, there was a projection of a substantial increase in demand for open learning innovations, encompassing OER, open textbooks, and Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) (Jacobi et al., 2013).

In February 2011, with UNESCO funding, an open meeting aimed to establish the OERu, a project building a parallel learning universe for more affordable education. Now a global initiative, OERu includes institutions from five continents, collaborating to broaden access and is a formal project of the UNESCO-Commonwealth of Learning (COL) OER Chair network (Open Educational Resources University, n.d.).

At this stage, the term OEP began to take clearer shape as introduced by OPAL (Open Educational Quality Initiative, 2011) as ‘a set of activities around instructional design and implementation of events and processes intended to support learning. They also include the creation, use and repurposing of Open Educational Resources (OER) and their adaptation to the contextual setting. They are documented in a portable format and made openly available’ (p. 13). As the concept of OEP gained momentum, Cronin (2017) introduced OEP by encompassing OER, pedagogies, and the sharing of teaching practices. Cronin’s work is noteworthy as it highlights that academics integrating OEP into their teaching do so in four dimensions:

- Balancing privacy and openness: This dimension involves managing digital identity boundaries and carefully considering teacher-student interactions in online spaces.

- Developing digital literacies: This involves academics developing proficiency in social media use and encouraging students to cultivate digital identities, fostering overall digital literacy.

- Recognising the importance of social learning: This requires understanding of theories of social learning such as social constructivism and sociocultural theory that emphasise the importance of learners being actively involved in the learning process.

- Challenging conventional expectations associated with the traditional teaching role: This involves academics embracing broader identities, viewing themselves as learners, dismantling lecturer-student barriers, and demonstrating care for students such as creating different communication channels (e.g., communicating with students via X previously known as Twitter) (Cronin, 2017).

Meanwhile, scholars like Weller (2014) and Wiley (2013) emphasised the term ‘open pedagogy’ that became closely associated with OEP. Both Weller and Wiley contributed significantly to expanding on integrating OEP into learning activities and teaching practices. For instance, Wiley’s significant contribution lies in defining the practical set of five activities in using OER or what is now known as the 5R activities—retain, revise, remix, reuse and redistribute (Wiley, n.d.). These activities provide a foundation for designing learning approaches for integrating OEP in learning and teaching. Wiley and Hilton (2018) further defined open pedagogy as a shift towards student-centred, flexible learning experiences, emphasising trust in students and adaptability based on learner needs.

UTS Learning Design Meetup community: Adopting OEP with David Wiley

Back in March 2021, I invited David Wiley to share his thoughts with the “UTS Learning Design Meetup community” about adopting OEP. Demonstrating through a couple of examples, David showed how the 5R’s enable students to engage in content through collaboratively creating an enhanced version of an existing open textbook and students reusing videos to create a debate of ‘wikis vs blogs’ by imitating the voices of Kennedy and Nixon. The following video is a 15-minute snippet from the meetup where David elaborates on those ideas.

Open Education in Australian higher education

The initial phases of open education in Australia were predominantly government-led initiatives that were committed to demonstrating transparency, information sharing, and access to publicly funded research projects. This is demonstrated by government-focused initiatives such as Australian Government Policy on Open-Source Software, Government 2.0 and Australian Government Open Access and Licensing Framework (AusGOAL), which paved the way for the Australian higher education sector to follow (Bossu, 2016, pp. 15-16).

Australian higher education institutions are positioned towards the late majority of what is known as Rogers’ innovation-adoption curve (Rogers, 2003, pp. 35-36), particularly in joining the open education movement. However, over the last two decades, there have been considerable efforts across Australian universities towards OEP, where innovative projects and initiatives take place. The following are some of the examples of OEP in the Australian higher education sector:

- The Open textbooks at La Trobe project demonstrates the value of modern curriculum in providing flexibility in developing educational resources and enhancing affordability for students. Dr David Walker from La Trobe’s School of Business highlighted that ‘this [adopting open textbook] has also enabled me to structure the content and frame the questions and topics more precisely to the things we want to cover’. Associate Professor Tanya Serry, School of Education, also emphasised the contribution to students’ wellbeing as she mentions that ‘the open textbook for this core 1st year subject has generated up to $45,650 of student cost savings by replacing a traditional commercial text’.

- University of South Australia (UniSA) Textbook Minimisation Project: Between 2020 and 2022, the Library and the Teaching Innovation Unit at UniSA implemented a pilot project with the aim of minimising course material costs for students. The university is actively working to reduce the number of textbooks students need to purchase during their program of study by transitioning certain courses from traditional textbooks to high-quality research-driven resources. This significant initiative has already saved UniSA students a total of $9 million in textbook costs. Two crucial outcomes have emerged from this effort: firstly, the integration of this initiative into Action Item 2.7 of the University’s Academic Enterprise Plan 2021-2025 as a strategic priority, and secondly, under the direction of the Academic Strategy, Standards, and Quality Committee (ASSQC), the Library is now incorporating the minimisation of student textbook costs as a ‘business as usual’ activity.

- University of Southern Queensland OEP Grants: Learning and Teaching Staff Scholarships provide grants to aid a USQ staff member or a team in enhancing their leadership in and approaches to advancing students’ educational experiences and graduate outcomes. Several academics shared their experience about this initiative, stating that these scholarships empower them to enhance their pedagogical skills, leading to publications, presentations, and increased impact while concurrently engaging in projects including developing renewable assessments and open textbooks.

- The Council of Australian University Librarians (CAUL) and the OER Collective: an organisation representing the university librarians or library directors of Australian universities. CAUL is committed to advancing open access within the sector, helping institutions implement, communicate, deliver, and evaluate their open access initiatives. CAUL is also committed to raise awareness of OER with government and higher education sector stakeholders through professional development programs. The CAUL OER Collective initiative has also been introduced to develop capacity for publishing open textbooks and other educational resources, working collaboratively to promote OER within the broader agenda of OEP across Australian higher educational institutions and offering a publishing platform for authors from the Australian universities.

It is important to note that the creation of the textbook you’re reading was made possible through a CAUL grant awarded to the authors. This grant has allowed us to offer learning designers in the Australasian context a comprehensive resource that aligns with the distinctive aspects of the learning design profession, both in theory and practice.

This brief exploration underscores the evolution of the OEP concept and its proliferation in Australian higher education, forming a starting point for considering their relevance in the context of socially just learning design. As learning designers, we stand at a strategic vantage point to actively contribute to the realisation of the overarching objectives of OE. Our engagement can take the form of implementing and cultivating OEP to expand access, as well as advocating for inclusivity through the incorporation of OEP principles in higher education.

OEP and learning designers

Nowadays, open education definitions are often amalgamated into OER; therefore, it is crucial for learning designers to use these terms accurately when communicating with stakeholders. Clear understanding of applications of OEP is vital when incorporating them into the learning design practice, whether through content creation, developing activities and assessments, use of technology, communication or faculties relationships.

As learning designers, we play a pivotal role in advancing OEP in higher educational institutions. Delving into the opportunities within learning design requires thoughtful consideration, deep reflection on the potential impact, and careful decision-making to effectively embrace and implement OEP. The following activity provides a short list of just a few practices in which learning designers can actively engage to promote OEP.

Exercises

As you read through these, consider which practices you can promptly incorporate into your work. Reflect on areas within your workplace that may have gaps, and identify how one of the OEP below can address them. Also, consider evaluating which of these practices are inherent to your learning design role. Finally, think about whether there are practices that you will be incorporating into your work over the long term.

- Creation and adaptation of OER: Learning designers are inherently capable of developing OER or adapting existing resources to suit specific educational needs. For example, through utilising Wiley’s 5 Rs, you can consider developing interactive H5P content and sharing in H5P OERHub, sharing videos in Kaltura, learning elements in Canvas Commons or enhancing accessibility of existing OER. Nevertheless, this may entail the challenge of navigating tension when collaborating with academics and senior management who may not embrace OEP (Roberts et al., 2022).

- Integration of OEP into learning design: Embedding principles of OEP into the instructional design process ensures that courses and learning materials are designed with openness in mind. This includes using content that is published under open licenses, ensuring proper attribution of materials published under open licenses and public domain, adopting open learning design models such as ABC Learning Design, and developing reusable teaching resources such as the UTS Adaptable Resources for Teaching with Technology resource collection and Equity Unbound online community.

- Promotion of open pedagogy: Learning designers can advocate for and incorporate open pedagogical practices, which involve engaging students in the creation and sharing of knowledge. This might include collaborative projects for creating OER, student-generated content, and renewable assessments. As learning designers, our approach to engaging academics in open pedagogy involves presenting practical examples for adoption of approaches to open pedagogy, rather than offering a theoretical overview. For example, the Open Pedagogy Notebook curates valuable resources for educators and learning designers who are seeking to delve deeper into open pedagogy, offering a range of evidence based examples from classroom practices.

- Training and professional development: Providing training and professional development opportunities for academics on OEP ensures that the broader educational community is aware of and skilled in implementing open approaches. This can be through running workshops and generating instructional resources such as the UTS resource collection Integrating Open Education Resources into your teaching.

- Advocacy for OEP: This can involve encouraging academics to share learning materials, raising awareness of the benefits of OEP in teaching and learning, and engaging in conversations with senior management and key stakeholders in higher educational institutions. It is important to ensure that these efforts align with institutional strategic goals, emphasising the value that OEP brings to the overall educational mission. For example, the OER Advocacy Toolkit, developed under the CAUL Enabling a Modern Curriculum OER Advocacy Project, serves as a comprehensive reference for advocates of OEP in higher educational institutions. The Toolkit includes information, resources, checklists, and practical ideas for effectively communicating with various stakeholders, including academics, librarians, teaching and learning committees, and university executives.

- Accessibility and inclusivity: As learning designers, we weave inclusivity into our work. OER hold the potential for ensuring accessible and inclusive learning. The fact that OER allow for adaptation, reuse, remix, and repurpose means we can use any OER to translate, create subtitles, and enhance content by adding alt text to images, among other improvements. This signifies that OEP help us cater to different learning styles, provide alternative formats, and ensure content is usable by individuals with various abilities. As a good practice, checking accessibility of H5P elements can be vital given the popularity of the tool. A good example is the H5P Accessibility tool by Libre Studio, which helps assessing and evaluating accessibility of H5P activities.

- Community engagement: Actively participating in the open education community such as Open Education Global, and special interest groups such as Australasian Open Educational Practices Special Interest Group allows librarians and learning designers to share insights, collaborate on projects, and stay informed about best practices and emerging trends in the field.

OEP encompasses skills and approaches that are inherent in learning design. As learning designers working directly with faculties, we can deliberately integrate these strategies into our practice. This will enable us to make meaningful contributions to the learning and teaching ecosystem, fostering collaboration, accessibility, and the widespread sharing of knowledge.

Open pedagogy: From theory to practice

The term open pedagogy has been introduced in the literature as a concept that revolves around making educational resources freely available, encouraging collaboration, and involving students in the creation and sharing of knowledge (Tietjen & Asino, 2021). Open pedagogy goes beyond that, as it entails not only making resources accessible but also influencing and transforming the methods and approaches used in teaching.

DeRosa and Jhangiani (2017) define open pedagogy as a dynamic and ‘contested site of praxis’, where theories of learning, teaching, technology, and social justice intersect, guiding the ongoing development of educational practices and structures. It embodies an access-oriented commitment to learner-driven education, involving the intentional design of architectures and the use of tools that empower students to actively contribute to and shape the public knowledge commons in which they participate.

Wiley and Hilton (2018) underscore the idea that students learn best through hands-on experiences. They argue that copyright laws restrict various educational activities (like copying or creating derivative works without permission), limiting students’ learning options. OER with their permissions for the 5R activities (retain, revise, remix, reuse and redistribute), remove these limitations. The advantages of using open licenses extend to facilitating pedagogical approaches that are otherwise unattainable when working with copyrighted materials (DeRosa & Robison, 2017). Therefore, when using OER instead of traditional copyrighted resources, students have the freedom to engage in a wider range of activities and, consequently, to learn in more diverse ways. Further, Fatayer and Tualaulelei (2023) have argued that learning activities should take place in socially relevant settings that allow knowledge to be cognitively mediated between two or more people. In the context of renewable assessments, defined by David Wiley as assessments that produce meaningful and valuable artifacts that contribute positively to the world and can be extended, revised, and improved upon by future students and others, the process of learning becomes more explicit as students engage in the negotiation of knowledge with academics, fellow students, and professionals, concurrently contributing to the development of student-generated OER. Students may then share their growing knowledge with people other than those who are assessing their assignments and they become a member of a learning community (Fatayer & Tualaulelei, 2023). It is important to point out that such inclusive practice of engaging students with different stakeholders in the knowledge development process is core to OEP and a result of openness as a pedagogical approach. Importantly, OEP are recognised for their economic advantages in terms of cost savings for students. An additional and often overlooked benefit is the engagement of students in the learning process.

The following H5P element is adapted from ‘Attributes of Open Pedagogy’ by Bronwyn Hegarty, originally licensed under CC BY 3.0. The new derivative is an H5P accordion redesigned for accessibility, incorporating resources and tools specifically intended for learning designers and redesigned to include examples of each attribute.

Adapted from Attributes of Open Pedagogy by Bronwyn Hegarty, licensed under CC BY 3.0.

Paskevicius and Irvine (2019) suggest that OEP constitute a developing approach to learning design, incorporating elements from established models of constructivist and networked pedagogy. This involves leveraging open software tools and content to innovate the creation and dissemination of learning materials and assessments.

The previous section introduced different tools for adopting open pedagogy and suggested tools that can be utilised by learning designers to develop activities that are informed by open pedagogy. Among the impactful approaches is utilising renewable assessments. Renewable assessment, as exemplified by Wiley’s concept of “renewable assignments,” (Wiley & Hilton, 2018) is a pedagogical approach that integrates constructionism and openness within OER-enabled teaching. In contrast to “disposable assignments,” where the work is understood to be temporary and discarded after grading, renewable assignments aim to serve dual purposes. They not only facilitate individual student learning but also contribute to the creation or enhancement of OER that can benefit the wider learning community. This approach underscores the idea that assessments can be valuable beyond their immediate use, providing lasting educational value by producing resources that are shared and reused by others.

As learning designers, embracing a model for renewable assessment is in line with principles of co-creation, student agency, and ownership of learning, contributing to the development of valuable, reusable educational resources. The following section provides an evidence-based approach for constructing an OER development model. This model aims to sustain OER in higher education by leveraging renewable assessments.

OER development model

The concept of student-generated content, originating from user-generated content, has gained prominence in formal learning environments. The term ‘student-generated content’ was first used by Sener (2007) and encompasses various terms such as ‘learner-generated content’ (Pérez-Mateo et al., 2011) and ‘student as producer’ (Neary, 2010) and is utilised in teaching approaches like project-based learning and group work. When students work together on assignments, they generate extra brainpower called ‘cognitive surplus’. This term, coined by Shirky (2010) in his book The Cognitive Surplus, describes the abundance of content created through activities that people generate when they collaborate online. This surplus leads to creative outcomes through activities like Wikipedia.

The proliferation of content generation tools, such as blogs, wikis, and social networking sites, has made it easier to design collaborative learning activities. Importantly, these technologies enhance the learning experience, promote digital literacy, and support active learning (Mason & Rennie, 2008; Sener, 2007).

Crafting effective learning design models is crucial for successful teaching with technology in today’s educational landscape. This section presents a learning design model that offers clear instructions and adaptable resources, catering to various disciplines.

Three-stage model for student-generated OER

At the outset, a model was proposed where students and academics developed OER as learning artefacts through a three-step process: creating, evaluating and publishing (Fatayer, 2016). The following H5P interactive elaborates on the OER development model and presents two case studies of model integration into undergraduate and postgraduate studies.

By guiding the implementation of this model and ensuring compliance with open access and intellectual property policies, learning designers contribute to the broader goal of making educational resources freely accessible to a wider audience and extending the benefits of student work to several communal goals. Finally, it is important to note that this knowledge generation not only benefits the students themselves but also enhances the availability of quality educational materials for learners everywhere.

OER and open textbooks

Open education, encompassing content, practices, policy, and a global community, offers the unprecedented opportunity for universal access to cost-free, high-quality, open learning resources. This educational revolution is driven by OER, materials freely shared with legal permissions, empowering learners and educators worldwide.

According to Creative Commons (n.d.), OER have become important in learning and teaching due to several key factors.

- Storage: The digital nature of educational resources allows for easy storage, duplication, and distribution at minimal cost.

- Access: The public access of content and the widespread availability of the internet simplifies the process of sharing digital content with the public.

- Licensing: Legal sharing of content using Creative Commons licenses as they play a pivotal role by providing a straightforward and legal framework for individuals to both retain copyright and share educational resources openly with a global audience.

- Adaptability and reusability: OER’s adaptability nature enhances inclusivity in learning and teaching. The reusability of OER allows educators to tailor materials to accommodate the diverse needs of learners, including those with different learning styles, languages, or cultural backgrounds.

These combined elements have facilitated the emergence of OER in different learning environments.

Why OER?

Watch the following video and think about how Open Educational Resources align with your role as a learning designer and your commitment to enhancing student learning experiences.

Certainly, open textbooks are among the most prevalent and widely recognised forms of OER. Open textbooks are typically available in digital formats, making them easy to store, duplicate, and distribute at minimal cost. Importantly, traditional textbooks restrict pedagogical choices (Jhangiani et al., 2016), which results in constraining the learning experience for individuals with diverse learning preferences. However, through the creation and adoption of open textbooks, educators and learners gain the flexibility to customise the content to meet their specific needs and teaching priorities. For example, OpenStax is a non-profit organisation that offers a collection of free, peer-reviewed, openly licensed textbooks via their website. Academics can customise these resources to suit the diverse needs of their students, whether by translating content into different languages, adding supplementary materials, or structuring the material to accommodate various learning styles. This adaptability ensures that open textbooks can cater to a wide range of learners, promoting inclusivity and accessibility in education.

The adoption of open textbooks in learning and teaching has the potential to achieve two significant outcomes: it can significantly reduce the financial burden on students, particularly those from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds, and enhance their prospects for academic success. This transformative impact aligns with the concept of redistributive justice, one of the core principles of social justice within open education, as articulated by Lambert (2018).

In addition to redistributive justice, Lambert (2018) proposes that open education encompasses two other vital dimensions of social justice: recognitive justice and representational justice, both of which are emerging areas in the open education landscape. Recognitive justice focuses on the inclusion of diverse perspectives, images, and case studies within educational resources, fostering a broader and more inclusive educational experience. Representational justice, on the other hand, emphasises the amplification of voices from marginalised groups in textbooks and the open curriculum, ensuring that their narratives are both heard and respected (Lambert, 2018).

In their open textbook, Tualaulelei (2020) and her postgraduate students, present an example of utilising a renewable assessment approach. Importantly, this collaborative approach of generating open textbooks with students provides a practical example that reflects Lambert’s (2018) framework of redistributive, recognitive and representational justice.

Renewable assignments show promise for perspective transformation as students will repurpose their assignment artefacts for a broader professional audience and step more fully into their future professional identities.

According to Tualaulelei and Green (2022), this approach helped ‘to flatten out hierarchies within social structures such as the teaching profession’ and engaged students in developing resources that address concerns related to reconciliation and intercultural education and continuing professional development or professional learning.

OER, open textbooks and learning designers

As learning designers, we recognise that OEP hold the promise of broadening access and championing inclusivity. It is imperative for us to comprehend the effective approaches for developing OER and open textbooks. Given our close partnerships with academics, it becomes essential to raise awareness among them about the available opportunities in the realm of OEP. As our understanding of the potential of OEP in enriching the learning experience deepens, we are committed to leveraging existing resources that align with our mission of fostering equitable, inclusive, and diverse education.

Approaches to open textbooks development

I was interested in the different approaches for generating open textbooks and integration in learning and teaching. I reached out to a few people in my network and interviewed them about their techniques. I was keen to know about the motives behind the decision to create and publish an open textbook rather than using traditional publishing methods, finding content, support to get the book reviewed and published, timeframe from start to publish and the impact on student learning and engagement.

Read the blog and watch the three interviews.

The three examples above can be used as insights for us as learning designers on adopting OEP in our daily work. Importantly, we can consider several concrete actions to address the issues of inequitable access and exclusion of marginalised voices as highlighted in the following work by Andersen (2022).

Example of adapting open textbooks

Enhancing Inclusion, Diversity, Equity and Accessibility (IDEA) in Open Educational Resources (OER) was developed by Nikki Andersen, Open Education Librarian at the University of Southern Queensland, to provide the Australian OER content developers with practical strategies for producing diverse, inclusive and accessible OER and open textbooks. The work is an adaptation of Improving Representation and Diversity in OER Materials by OpenStax. The work has also received the 2022 Australian Award University Teaching Citation for Outstanding Contributions to Student Learning and OEGlobal award for Diversity, Equity & Inclusion 2023.

According to Andersen (2022): Content advertised as ‘open access’ and ‘freely accessible’ may give the impression that OER are universally accessible, but many users still face inequitable barriers to access. Additionally, access doesn’t equal inclusion. Textbooks often express sexist and racist content and exclude marginalised voices. We need to consider how to contribute to a transformation and expand open access to resources to truly address diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

Learning design, copyright and Creative Commons

As learning designers, we are required to pay attention to using and reusing materials to create new content in the learning management system or any instructional resources. However, often we question whether the content we use is covered by copyright. The copyright area is broad, and it is not the intention of this section to delve into legalese, but rather to highlight the aspects of copyright that are important to learning designers working in the Australian higher education sector.

Copyright is the automatic legal protection given to all original work that we create in a materialistic format. Copyright applies as soon as a work has been put into a material form such as being written down or recorded in some way, which applies to both print and digital material. However, copyright is for protection given to the expression of an idea and not the ideas themselves.

The concept of copyright originated in 1709, making it a long-standing idea. The main reasons for the need of copyright law were to protect the publishing and printing industries and to promote the advancement of knowledge. Its main mission was to protect authors’ ideas and advance knowledge. Copyright law has two main reasons behind it, though the reasons may differ in different legal systems.

- Utilitarian: To encourage authors by offering benefits of their work, such as commercial rewards and societal advantages.

- Author’s rights: To recognise and safeguard the bond between authors and their creative work. It is based on moral rights, which ensures authors receive credit for their work and protect the integrity of their creations.

The utilitarian rationale is more commonly found in common law systems, while the author’s rights rationale has historical connections to civil law systems.

Copyright covers various works, such as art, literature, recordings, and broadcasts. However, ideas, concepts, methods, styles, facts, names, and titles are not copyrighted; they may be protected under different laws like patents or trademarks. When using indigenous cultural and intellectual property, it is essential to respect relevant protocols and ethical guidelines.

It is important to note that copyright law might differ from country to country. So here in Australia, we do not need to register work in some way or have the copyright symbol on it to be protected. Therefore, images, text, and videos that you may find on the Internet are not free to use if they do not have a copyright notice! Copyright also lasts for a very long time, generally for 70 years after the creators’ death. After the copyright has expired, the work then enters into the public domain, which means you can reuse it however you like.

The copyright owner holds exclusive economic rights, including publishing, communicating to the public, copying, reproducing, performing, and adapting the work. Additionally, moral rights safeguard the creator’s personal rights, such as the right to attribution and protection of the work’s integrity.

Copyright questions I heard from learning designers

Copyright laws in Australia protect the intellectual property of learning designers and creators. Copyright automatically applies to original works once they are created, and it grants the creator exclusive rights to use and distribute their work. This means that learning designers have certain rights and protections for their educational materials and content. However, this may change if you belong to a higher educational institution in Australia. When it comes to learning designers working in Australian higher educational institutions, copyright, is still, of utmost importance. We are usually responsible for creating and designing educational materials, online subjects, and other content used in teaching and learning. In most Australian higher education institutions, we often collaborate with educators and subject matter experts to develop educational materials, instructional resources, and interactive content. This content can include lecture notes, presentations, multimedia, assessments, and more.

As my experience primarily resides in the learning design sphere, I often encounter intriguing questions from colleagues regarding copyright and Creative Commons. While I am not an expert in copyright, I respond to all questions from my perspective and recommend that they reach out to the university library’s copyright officer for legal advice. In the following paragraphs, I have categorised each question and listed both the question and the corresponding response under each category.

To ensure compliance with copyright laws and policies, as learning designers we should stay informed about copyright regulations, seek appropriate permissions when necessary, and work closely with our institution’s legal and intellectual property experts.

Creative Commons essentials for learning designers

While there is a vast amount to discuss regarding Creative Commons, immersing oneself in the content of the Creative Commons Certificate open textbook can offer a thorough guide to effectively utilising Creative Commons licenses within educational environments.

Creative Commons story

The creators of Creative Commons acknowledged the disparity between the possibilities enabled by technology and the limitations imposed by copyright. They offered an alternative method for creators who wish to distribute their work. This approach is now embraced by countless creators worldwide. It all began with the case of Eldred v. Ashcroft (2003), which was argued in the Supreme Court of the United States by Lawrence Lessig, a Stanford law professor who would go on to found Creative Commons. For detailed background, listen to this podcast about the Creative Commons story

For learning designers, obtaining a fundamental grasp of Creative Commons licenses may appear adequate. Yet, as you delve deeper into working with OER and creating or publishing them, you’ll discover certain complexities that demand a thorough understanding of the nuances and legal terms within the licenses.

Creative Commons explainer: NonCommercial and ShareAlike

Among the different types of Creative Commons licenses, the NonCommercial (NC) restriction and the ShareAlike (SA) condition often pose challenges for many, including novices and experienced users alike. The blog post titled ‘Creative Commons Explained: NonCommercial and ShareAlike’ offers an in-depth explanation of both types, illustrated with examples from academic contexts.

Hot topics in open learning design

Open education and decolonising the curriculum.

“Decolonising is not about deleting knowledge or histories that have been developed in the West or colonial nations; rather it is to situate the histories and knowledges that do not originate from the West in the context of imperialism, colonialism and power and to consider why these have been marginalised and decentred.” Rowena Arshad, University of Edinburgh (Arshad, 2021, para. 4).

One of the key aspects of decolonising the curriculum is to incorporate diverse perspectives and voices from different cultures and regions. Academics can use OER that are freely available and accessible to all learners and adapt these resources to produce inclusive learning experiences. By curating OER from various sources, including non-Western authors, Indigenous knowledges, and marginalised communities, academics can create a more inclusive curriculum that challenges Eurocentric perspectives.

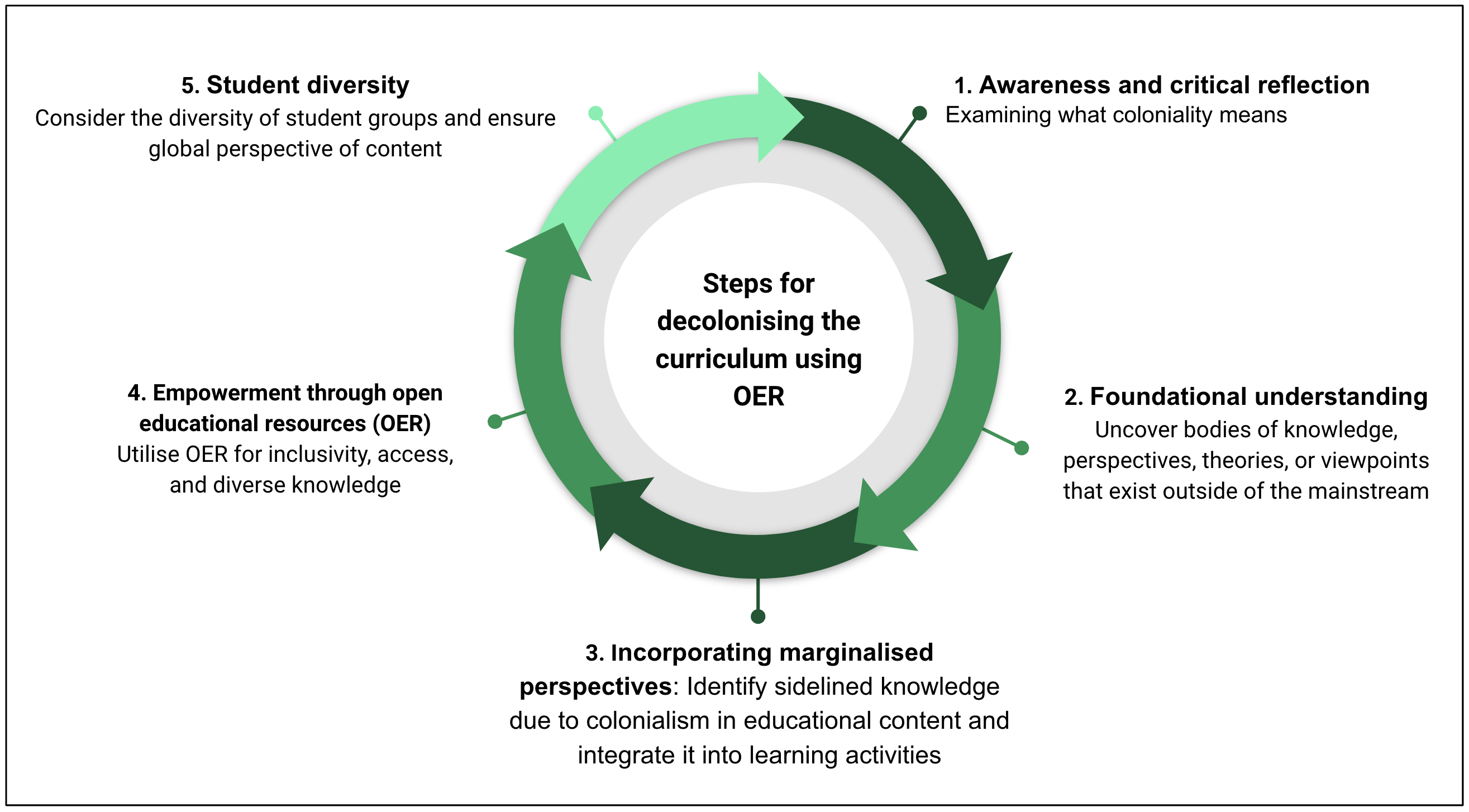

Educational materials that utilise OEP and OER enable the integration of multiple voices and perspectives and produce student-centered content. Importantly, these practices aim to address social injustice in the classroom. In her article ‘Decolonising the curriculum – how do I get started?’, Rowena Arshad suggests that decolonising the curriculum has to be contextual to our discipline and subject areas. She proposes four guiding points that can be used in decolonising the curriculum approach. The following points integrate OER/OEP as the fifth guiding point to demonstrate their introduction in Arshad’s guide and to reveal where to revise the curriculum, spotting chances for decolonisation.

Awareness and critical reflection: Start by examining what coloniality means and why decolonising the curriculum is important as part of our commitment to justice. Read Walter D. Mignolo’s 2017 paper ‘Coloniality is far from over, and so must be decoloniality’. This paper emphasises that the impact of colonialism persists in various aspects of modern society.

Foundational understanding: Review your subject materials to uncover bodies of knowledge, perspectives, theories, or viewpoints that exist outside of the mainstream or dominant narratives knowledge canons that may have been marginalised or disregarded due to colonial influences. Determine if there are perspectives, theories, or contributions that have been overshadowed by colonialism and should now be integrated into the subject’s discourse for meaningful discussion with students.

Incorporating marginalised perspectives: Identify side-lined knowledge due to colonialism in your educational content and integrate it into learning activities (e.g., ice-breaker, discussions boards, assessments, etc). Include various voices, re-imagine the learning content to encompass broader global and historical viewpoints.

Empowerment through Open Educational Resources (OER): Curate and identify OER to replace identified content. Ensure the chosen resources have open licenses for adaptability. A good start is in Indigenisation, Decolonisation and Cultural Inclusion. A common CC license used by an OER such as the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial (CC BY-NC) license is a good option. This license allows others to reuse, remix, and redistribute the resource as long as they provide appropriate attribution to the original creators and do not use it for commercial purposes. Another CC license, that can also be used, is the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license which allows even greater freedom for users, permitting both commercial and non-commercial use if attribution is given to the original authors.

Student diversity: Consider the diversity of your student groups and ensure that the learning content transcends Western perspectives, encompassing broader global frameworks.

Importantly, as learning designers it is crucial for us to continuously assess, gather feedback, and enhance content design to ensure its relevance to students’ diverse backgrounds.

Openness: From social justice to liberation

This hot topic holds great personal significance for me as it resonates with my cultural identity, as a first generation Palestinian in the diaspora, and underscores the transformative potential of openness in advancing social justice to achieve liberation. As I compose this chapter, the atrocities of the Israeli army on civilians in the Gaza Strip persist. Regrettably, by the time of completion, additional tragic incidents are anticipated, including the loss of innocent lives, particularly children, as a result of Israeli military actions and rocket attacks on civilian spaces such as refugee camps, educational institutions and hospitals. This has also resulted in the loss of lives of academics, artists, journalists, scientists, and historians. Furthermore, the atrocities of the occupation have extended to archives, libraries, museums, and historical buildings.

The educational system lies at the heart of this devastation, with the persistent war preventing approximately 608,000 students from exercising their fundamental right to school education, and interrupting the studies of over 90,000 university students. Moreover, the loss of 17 professors, 59 holders of Ph.D. degrees, and 18 individuals with master’s degrees has dealt a severe blow to the intellectual foundation of Gaza’s universities (Mediterranean Universities Union, n.d.).

Education serves as a moral compass for Palestinians as they strive for learning at all stages, making them the country with the lowest illiteracy rate in the world per capita. Palestinian universities stand as symbols of pride and resilience for the Palestinian people; however, due to the occupation, their participation in generating knowledge remains limited, encountering barriers imposed by the Israeli occupation (Alfoqahaa, 2015). Preserving lives is crucial, as is safeguarding human intellectual property. Through openness, Palestinians can find ways to preserve their knowledge and pave the way towards liberation.

Openness, as a transformative force for equity, goes beyond its role in facilitating learning and teaching through OER. It acts as a catalyst for liberation, providing a platform to disseminate narratives and facts that illuminate the persistent challenges endured by the indigenous people of Palestine. In doing so, it actively contributes to the discourse surrounding the 76 years of occupation, fostering awareness about injustice, correcting media misconceptions about the history of the land and emphasising the urgent need for global attention and support.

Yet, preserving knowledge amidst occupation poses significant challenges, often entailing serious risks. Under Israeli occupation, access to material goods and decent living standards are often considered privileges to Palestinians rather than basic human rights. Consequently, these factors deprive Palestinians of having a robust health system, an income to secure basic needs without having to resort to working in subhuman conditions, and proper education.

According to Itmazi (2020), in the Arab States, including Palestine, a notable concern arises from the insufficient availability of open digital content in the Arabic language. Currently, all Arabic content on the web constitutes less than 3% of global digital content. Furthermore, the absence of political strategies or action plans from Arab Ministries has been identified as a hindrance to the development and implementation of OER. It is critical to carry out awareness campaigns about the importance of creating, using, and sharing OER. Importantly, the available OER could be translated from other languages into Arabic and further recontextualised to meet the needs of Palestinian education.

Javiera Atenas writes on how her trip to Palestine changed her views on OEP, stating that ‘Opening up means to me to share, to do things in a transparent way, to collaborate, to support and to provide the tools for educators and students to be critical thinkers, to challenge and to question, to become communities and not to follow a rule that tells you if you are open enough according to someone else’s agenda, so just be open, under your own terms, share, distribute, communicate, participate, engage, thinking that before Open rules there are human rights, and that accessing quality education is one of these.’ (Atenas, 2017, chapter 8).

As previously discussed in this chapter, open education centres on principles such as access, agency, ownership, participation, and experience. It holds the potential to emerge as a significant global equaliser, empowering individuals worldwide to exercise their basic human right to education (Blessinger & Bliss, 2016, p. 11).

Importantly, in the Palestinian context, the role of openness in education extends beyond ensuring proper education. It has the potential to preserve historical events, narrate stories, and document innovations within a self-sufficient society. This entails preserving cultural heritage, documenting the innovations of Palestinian scientists, safeguarding patents from destruction, and offering a global platform for Palestinian artists and poets to persist in their noble call for liberation and justice (Mahn et al., 2020).

As learning designers, understanding the perspectives and needs of learners can inform the design decisions, therefore adopting human-centred approaches is usually seen as a core commitment in designing for the better, both for people and the planet. It is our ethical duty and commitment to design for better futures, acknowledge ethical responsibilities and to speak out against injustices. We cannot be learning designers who stay disconnected from brutal war crimes while claiming to operate from a space of empathy when we design for spaces, technology, and interfaces. Empathy, as we understand it, is the ability to feel deeply and resonate with the human experience.

Practical steps to support liberation through OEP

There are many ways we can consider to pave the way to liberation through an open education lens:

- Cultivate empathy for the enduring struggle of Palestinians over the long term.

- Educate ourselves on the history of the occupation dating back to 1948.

- Curate OER tailored to address the specific needs and infrastructural challenges (See OERs for Gaza).

- Challenge and rectify misconceptions by decolonising available resources.

The principles of open education pave the way for individuals across various learning design roles to contribute to a more informed, empathetic, and socially responsible approach to addressing the challenges posed by conflicts and displacements. As learning designers, our contribution can be through global awareness and solidarity, documenting and preserving narratives, as well as cultural preservation and restoration, to name a few possibilities.

Generative AI and Open Educational Practices

Part of this section is adapted from Getting Started: OER Publishing at BCcampus by BCcampus Open Education Team, available from https://opentextbc.ca/gettingstarted/chapter/generative-artificial-intelligence/#decisiontree under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The introduction of generative AI has brought a significant disruption in higher education, although it is worth noting that disruption is the norm in the higher education sector. Before exploring generative AI and OEP more extensively, it is crucial to recognise that, at the time of writing, higher education is primarily reacting to the emergence of generative AI. Numerous uncertainties surround the integration of these new technologies into learning and teaching. Consequently, this discussion will focus on examining potential applications of generative AI in the development of OER.

What is artificial intelligence (AI)?

UNESCO World Commission on the Ethics of Scientific Knowledge and Technology, UNESCO (2019) defines Artificial Intelligence (AI) into two distinct aspects: theoretical or scientific AI and pragmatic or technological AI. The theoretical aspect explores AI concepts and models to answer questions about human beings and other living things, intersecting with disciplines like philosophy, logic, linguistics, psychology, and cognitive science. It addresses questions about intelligence, distinguishing natural from artificial intelligence, the role of symbolic language in thought processes, and the possibility of achieving “strong AI” comparable to human intelligence. On the other hand, pragmatic or technological AI is engineering-oriented, leveraging branches of AI such as natural language processing, knowledge representation, machine learning, deep learning, computer vision, and robotics. It aims to create machines or programs capable of independently performing tasks that typically require human intelligence. The success of pragmatic AI is evident in its integration with information and communications technology (ICT), leading to widespread applications in areas like transport, medicine, communication, education, finance, law, military, marketing, customer services, and entertainment (UNESCO, 2019).

As technology develops, so too do the ways we define it. There is no single or fixed definition of AI, but there is common agreement that machines based on AI “are potentially capable of imitating or even exceeding human cognitive capacities, including sensing, language interaction, reasoning and analysis, problem solving, and even creativity” (UNESCO, 2019).

Generative artificial intelligence (AI) is a type of artificial intelligence used to create images, text, audio, video, computer code and other types of content via text prompts from a user. Generative AI exists in the form of a standalone tool or can be incorporated or integrated into other content creation tools for example ChatGPT for text, Dall-e for images, or GitHub for computer code to name a few. In his short blog, David Wiley (2023) has attempted to respond to the question of what impact generative AI is going to have on education by starting with the assumption that ‘Generative AI greatly reduces the degree to which access to expertise is an obstacle to education’. David’s initial thought sparked more questions such as, how will generative AI tools impact the development of OER by learning designers, especially considering they may not always be subject matter experts?

Using generative AI in developing OER

Some ways in which generative AI could be used when creating or adapting OER are as follows:

- To create questions sets, case studies, and other types of instructional resources.

- To analyse a photo to create alt text for accessibility purposes.

- To create illustrations and photo-realistic images for both decorative and instructional purposes.

- To generate scripts that can be used for videos and podcasts.

- To create instructional videos.

- To generate sentences, paragraphs, and chapters for a textbook.

- To analyse and create summaries of longer sections of text.

- To automate the creation of an audio version of text, usually for accessibility purposes.

- To translate text to another language.

Nonetheless, ensuring the quality of OER will remain a challenge that learning designers need to address. Generative AI tools can handle routine and bulk tasks, accelerating the content development process and reducing the necessity for expertise in all aspects of content creation. These tools also aid in generating accessible content, such as alt text. However, human intuition and an expert’s final touch are unlikely to become obsolete and remain a necessity to ensure the overall quality of content.

Intentional vs. unintentional use

With the proliferation of generative AI tools and the continual integration of these tools into other software packages, you may not know that a tool you are using to create learning materials is using generative AI. Therefore, these guidelines are intended to be interpreted with leniency and flexibility to allow for the possibility that generative AI use may not always be visible or apparent to the person who is using a tool. Here are guidelines to consider if you plan to use generative AI tools during the OER content creation process.

Considerations and risks

While these tools can be of great value, there are numerous ethical concerns and potential risks you should be aware of when you consider using generative AI tools to develop OER.

- Lack of transparency: The source of the training data and the programming logic used by many generative AI tools is not always made available to the public. Indeed, even the companies that develop the tools may not be able to explain exactly how they work, or how they arrived at the outputs they did.

- Bias: Because there is a lack of transparency in how the tools are constructed and what data is used to train them, this can lead to biases being present in the output.

- Accuracy: Generative AI systems can sometimes produce inaccurate or made-up answers (also referred to as hallucinations).

- Intellectual property (IP) and copyright: There are three areas where copyright and IP should be considered; the content that the AI tool has been trained with, the content that the AI tool generates, and using AI to generate summaries of copyrighted content.

- Use of content to train AI models: Many generative AI tools have been trained on copyrighted works often without the permission of copyright holders. While organizations such as Creative Commons argue that this use is considered fair use under current copyright legislation, there are a number of lawsuits where creators are arguing that AI tools are creating unauthorised derivatives. This also means that AI-generated content could be subject to copyright claims.

- Applying copyright to generated output: Legal decision and rulings around copyrighting AI generated content has been very clear in the United States. AI generated content is not human made and therefore cannot be protected by copyright. In Canada there has not been as definitive legal rulings around this, although the emerging consensus in Canada is that Canadian copyright law will follow closely with the US when it comes to copyright and AI due to the shared international copyright and trades agreements the two countries have with each other. To date, there isn’t a specific legal reference available for Australia’s stance on copyrighting AI-generated content.

- Using AI to generate summaries of copyrighted work: It is unlikely that using generative AI to summarise copyrighted content is a violation of copyright as the AI generated summary is machine and not human generated.

- Sustainability: Generative AI uses massive amounts of electricity to operate, which has led to examinations as to how environmentally sustainable generative AI is.

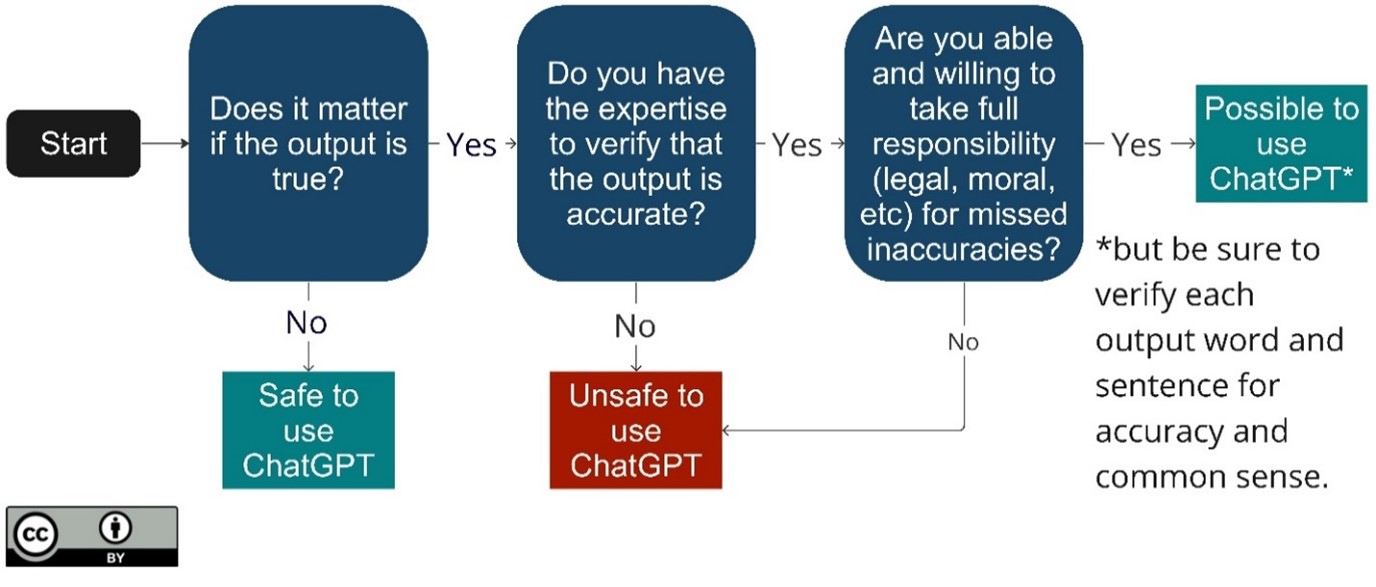

Is it safe to use ChatGPT?

Use the following flowchart to check if the content generated by GenAI is safe to use:

Is it safe to use ChatGPT image description

- Does it matter if the output is true?

- No. It is safe to use ChatGPT.

- Yes. Continue to next question.

- Do you have expertise to verify that the output is accurate?

- No. It is unsafe to use ChatGPT.

- Yes. Continue to next question.

- Are you able and willing to take full responsibility (legal, moral, etc.) for missed inaccuracies?

- No. It is unsafe to use ChatGPT.

- Yes. It is possible to use ChatGPT, but be sure to verify each output word and sentence for accuracy and common sense.

Key Takeaways

Guidelines and recommendations:

- Be cautious with your use of AI generated content. While we do provide some guidelines and suggestions, AI generated content is an area that is in considerable flux right now and these guidelines and recommendations may change as the field evolves.

- Manually review and assess all AI generated content for accuracy, appropriateness, and usefulness before including it in any OER. AI generated content should be reviewed by more than one subject matter expert to ensure the validity of the content. As an OER author, you are ultimately accountable for the content that you share in your OER, therefore you must manually verify the accuracy of the content.

- Closely review any AI generated content for bias, including language or images that reinforce cultural or societal stereotypes around race, ethnicity, colour, ancestry, place of origin, political beliefs, religion, marital status, family status, ability, sex, gender identity and expression, sexual orientation, age, and class and/or socioeconomic status. Consider reviewing and assessing the outputs of AI generated content using the lenses of equity, diversity and inclusion and ask whether the content aligns with these considerations.

- Do not use generative AI to generate content for an area or subject where you do not have the appropriate level of knowledge or understanding to verify the accuracy of the content.

- Be transparent about your use of generative AI. Just like attributing the reuse of open content, you should include statements within the OER that let others know that you have used generative AI in the creation of the OER. This should include:

- what content was generated

- what tools were used to generate the content, including links to the tool,

- how you used that tool (i.e., what prompts was the tool given that generated the content?)

- the date the content was generated

- what steps were taken to review the content to ensure it was valid and correct.

- As much of the legal consensus around AI generated content suggests AI created content is not copyrightable, you should not apply a Creative Commons license to AI generated content as Creative Commons licenses can only be applied to content that is copyrightable.

- You should avoid generating content that may include content that is protected by a trademark or patent. For example, you should avoid creating an image using an AI image generator that includes a trademarked corporate logo unless you are doing so under the purposes of Fair Use.

- If you use AI to create a summary of another work, you should ensure that you are familiar enough with the original work to determine whether or not the generated summary is an accurate representation of the original work before using the summary.

Evaluating OER

Publishing an OER is a valuable endeavour that requires careful planning, creation, and dissemination. The following sequence can be useful for learning designers to consider before publishing OER:

- Quality of content and use of third-party content

When evaluating the quality of content for OER, several crucial considerations come into play. Firstly, it is imperative to review the content for accuracy, ensuring it is free from errors. Additionally, a critical aspect of quality control involves addressing biases and conflicting information to present an unbiased and cohesive resource. The content should align with the values of the institution where its developed and should not convey messages contradictory to these principles. Furthermore, adherence to accessibility guidelines is essential to guarantee that the content can be accessed and utilised by all learners. In the case of third-party content incorporation, it is crucial to verify licenses for compatibility with the broader OER and ensure compliance with legal and ethical standards. This first step of the evaluation process is fundamental to maintaining high quality and the integrity of the OER.

Practical tool for OER development and evaluation in the Australian context

EmpoweredOER is a website and practical tool designed to guide the development and evaluation of inclusive OER. This platform provides simplified explanations and concrete examples of good practice. EmpoweredOER adapts the Equity Rubric for OER Evaluation developed by a non-profit organisation, Branch Alliance for Educator Diversity (BranchED) (Grunzke et al., 2021). Barber’s work (2023) incorporated into EmpoweredOER provides valuable insights into good practices, featuring illustrations from an Australian context. These practices are intricately woven into three overarching themes: (1) accessibility, (2) the intersection of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and inclusive open education, and (3) perspective and representation.

- Publishing guidelines

The process of license selection and definition is a crucial step in the creation and publication of OER. As you decide on how the work will be disseminated, consider the following:

-

- Firstly, and foremost, it is essential to carefully choose an appropriate license that aligns with the intended use and sharing of the OER.

- Secondly, to ensure institutional alignment and compliance, obtaining approval from the relevant academic unit or faculty is imperative, as this step helps validate the chosen license and the decision to publish the OER.

- Finally, a copyright officer’s advice should also be sought to address any potential copyright-related concerns and to maintain legal integrity. Copyright officers, who are most of the time embedded in university libraries, can identify and resolve any copyright issues that may arise during the development and sharing of the OER. This step in the evaluation process safeguards the proper dissemination of OER while upholding legal and institutional standards.

OER licensing tools

Open Attribution Builder

To simplify the process of licensing, an attribution builder tool developed by Open Washington OER Network ( Washington State Board for Community and Technical Colleges, n.d) can be utilised to generate the license, ensuring that it accurately reflects the desired permissions and restrictions.

This tool facilitates convenient citation of open materials by automatically generating attribution as you fill out a form. It is designed specifically for citing openly distributed work, including content licensed by Creative Commons or released into the public domain. Keep in mind that the tool offers a default attribution statement, which can be modified to better suit specific needs.

Open Education Licensing Toolkit

The OEL Toolkit is a web application designed to assist teaching staff in Australian higher education institutions. It is a decision tree system that provides easy access to relevant support resources regarding open educational resources. The tool was developed by a team from Swinburne University and the University of Tasmania and was supported by the Australian Government Office for Learning and Teaching.

- Technological considerations

When it comes to hosting OER, several essential considerations need to be addressed. Firstly, it is crucial to determine the most suitable platform or location for hosting the OER content, ensuring it aligns with your goals and target audience. Once hosted, there should be a well-defined plan in place for the ongoing maintenance and preservation of the OER to ensure its long-term accessibility and relevance. Additionally, it is important to review the terms and conditions of global OER repositories, such as OER Commons, to confirm that they align with your objectives and any licensing agreements you’ve chosen for your OER. These repositories can provide valuable platforms for sharing your educational resources.Recommendations for suitable OER repositories should be made considering the nature of your resource and its intended audience. For example, OER Commons is recommended as a publishing platform. It is essential to ensure that publishers, if involved, adhere to the original purpose of making the resource open and accessible.Lastly, the inclusion of sufficient meta-data attributes is crucial for effective discovery and categorisation of the OER. These attributes enhance the resource’s visibility and usability, facilitating its access by educators and learners seeking relevant educational materials.

OER infrastructure

Open Educational Resources Search Index

OERSI, or the Open Educational Resources Search Index, is a search engine designed for open educational materials in higher education. Launched in 2021, it connects various OER repositories, including initiatives, university libraries, and subject-specific repositories. OERSI, developed as an open-source service, does not store content but centralises metadata for uniform searching. Users can integrate OERSI into other platforms and customise searches based on specific criteria. The project encourages open participation, allowing feedback, bug reporting, and feature requests through transparent processes on the GitLab platform.

OER Commons

Developed in 2007 by Institute for the Study of Knowledge Management in Education (ISKME), OER Commons provides a robust infrastructure for curriculum experts and instructors at all levels to discover high-quality OER that can be downloaded directly through the curated resources. Individual learning content developers can also share their own materials directly through this platform.

ISKME’s technology platform, tools, and metadata enhancements in OER Commons emphasise fostering accessibility and inclusive design principles. By aggregating resources and standardising metadata from OER content providers, the site supports knowledge sharing and access to teaching and learning materials, strategies, and curricula online.

Conclusion

This chapter has presented practical approaches for the adoption of OEP in higher education, offering insights from Australia and other places around the world. The concept of openness holds immense potential to enrich higher education, particularly as it aligns with strategies commonly embraced by universities, emphasising principles of social justice. Key takeaways from this chapter can be summarised as follows:

- In our roles as learning designers, it is imperative that we intentionally approach open education with confidence and courage, recognising that our unique qualifications empower us to leverage the 5Rs (retain, revise, remix, reuse and redistribute) effectively in our learning design processes.

- As learning designers, a thorough understanding of the fundamentals of open education is indispensable for our daily interactions with academics. Utilising the insights of open pedagogy provides a common language that bridges the understanding gap between us and academics, making it essential to be cognisant of diverse teaching approaches grounded in open pedagogy.

- In our routine tasks, we often encounter inquiries about open textbooks or copyrights, typically better addressed by library copyright officers. However, it is crucial to share our insights with academics, guiding them in unpacking the benefits of open textbooks. This involves empowering them to infuse their perspectives into a curriculum that might be outdated and inherently biased.

- Lastly, delving deeper into the role of OEP beyond social justice becomes increasingly vital in the face of the disruptions we experience, whether due to political challenges or technological advancements. Open education holds the potential to decolonise and elevate the quality of education, enabling us to foster inclusivity for everyone in the learning journey.

I unequivocally concur with Ash Barber’s (2023) assertion in her paper that ‘… the reality is OER alone cannot achieve this goal [inclusive, equitable and diverse education] because OER itself is not the goal. OER is the vehicle to the goal of dismantling the education exclusion zone’.

Similarly, the exclusion zone within the learning content we construct, the interactivity infused into resources, and the innovations embedded in our designs must be dismantled . This dismantling need is essential to amplify the voices of those at the margins and foster inclusivity for everyone within the learning environment.

References

Alfoqahaa, S. A. A. Q. (2015). Economics of higher education under occupation: The case of Palestine. Journal of Arts and Humanities, 4(10), 25-43.

Andersen, N. (2022). Enhancing inclusion, diversity, equity and accessibility (IDEA) in open educational resources (OER). https://usq.pressbooks.pub/diversityandinclusionforoer/

Arshad, R. (2021). Decolonising the curriculum – how do I get started? Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/decolonising-curriculum-how-do-i-get-started

Atenas, J. (2017). Open education in Palestine: A tool for liberation. In M. Bali, C. Cronin, L. Czerniewicz, R. DeRosa, & R. Jhangiani (Eds.), Open at the margins: Critical perspectives on open education (ch. 8). Pressbooks. https://press.rebus.community/openatthemargins/chapter/open-education-in-palestine-a-tool-for-liberation/

Atenas, J., Havemann, L., Cronin, C., Rodés, V., Lesko, I., Stacey, P., … & Villar, D. (2022). Defining and developing ‘enabling’ open education policies in higher education. In UNESCO World Higher Education Conference, 18-22 May 2022. Barcelona, Spain. https://oars.uos.ac.uk/2481/

Barber, A. (2023). Dismantling the education exclusion zone: Empowering OER authors towards inclusive design. In T. Cochrane, V. Narayan, C. Brown, K. MacCallum, E. Bone, C. Deneen, R. Vanderburg, & B. Hurren (Eds.), People, partnerships and pedagogies (pp. 281–285). Proceedings ASCILITE 2023. Christchurch, N.Z. https://publications.ascilite.org/index.php/APUB/article/view/560/597

Blessinger, P., & Bliss, T. J. (Eds.). (2018). Open education: International perspectives in higher education. Open Book Publisher.

Bossu, C. (2016), Open educational practices in Australia. In F. Miao, S., Mishra, & R. McGreal (Eds.), Open educational resources: Policy, costs and transformation. UNESCO and Commonwealth of Learning. http://oasis.col.org/handle/11599/2306

Creative Commons. (n.d.). Unit 5: CC for educators. Creative commons certificate for educators, academic librarians and GLAM. https://certificates.creativecommons.org/cccertedu/

Cronin, C. (2017). Openness and praxis: Exploring the use of open educational practices in higher education. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(5), 15-34. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i5.3096