1.2 What do we mean by “people”?

Sarah Riley; Siobhán Healy-Cullen; Gareth Terry; Don Baken; and Aorangi Kora

Overview

People working in health psychology are involved in a range of research, policy development, and therapeutic practice that aims to support health and wellbeing, or prevent, or treat illness. How they do this work is shaped by the conceptual frameworks they have, including how they conceptualise the person whom they seek to help. This means that it is important for health psychologists to critically reflect on how they conceptualise people. You might be surprised at the variation. This chapter therefore asks the question: What kind of person are health psychologists thinking of?

Building on the previous chapter, which included a te ao Māori perspective for this question, here, we consider three approaches from Western traditions that offer different ways to conceptualise the person: (1) the biopsychosocial approach and how health psychologists address the “psycho” element with atomised models of universal psychological processes; (2) phenomenologically informed psychology which focuses on individual interpretations of their lived experience; and (3) social constructionist approaches that conceptualise the person as produced through, and thus inseparable from, their context. Throughout we give examples, often using coronary heart disease as a running theme to show the similarities and differences between the approaches when applied to the same health condition. In so doing, we cover the following learning objectives:

Learning objectives

- Understand that there are different ways to conceptualise the person.

- Explain why critical health psychologists are concerned with the individualist orientation in our discipline.

- Reflect on how these different ways to conceptualise the person produce different ways for psychologists to think about, and respond to, health issues.

Introduction

The New Zealand Psychological Society defines psychology as the scientific study of how people behave, learn, think, feel, and respond (New Zealand Psychological Society, 2024). This definition is similar to other professional psychological organisational definitions, such as the American Psychological Association’s description of psychology as the study of the mind and behaviour (American Psychological Association, 2024). These definitions are deliberately broad statements, designed to summarise a whole discipline in an accessible way. But to understand these relatively simple statements, we need a shared understanding of what we mean by “people”.

In Chapter 1.1, Kora and Brittain invited us into te ao Māori, a holistic worldview where people are made sense of through interconnected relationships across human, physical, and spiritual realms. Te ao Māori offers a unique, culturally grounded framing of people that differs from that usually implied in the definitions used by psychology organisations, the latter drawing on Western ideas of people as individuals ontologically separate to, if interacting with, other individuals and their environment.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, one of the opportunities of living in a society where Māori culture is recognised is being primed to understand that there are multiple ways to conceptualise what it means to be a person. This helps us engage with one of the important pou in critical health psychology, which is to notice our taken-for-granted understandings. We believe that reflecting on our taken-for-granted understandings increases our capacities to think about an issue. Critical reflection is thus the starting point for being able to envisage new, and more enhancing, ways of doing health.

Different frameworks for thinking about what it means to be a person can fundamentally shape how health psychologists think and practice. It is important to recognise that what we know shapes what we do, and what we know is only ever a partial perspective (for further discussion, see Gavey, 2018). The concepts we have about the world therefore represent some aspects of how we might see the world, but not others. This idea is neatly summarised in the expression “the map is not territory”. For example, a geologist’s map can tell you about the types of rock, while a travel map gives information about roads. The both offer different representations of the same land, and depending on context, one may be more, or less, useful to you. But neither of them are the territory. This is why another version of the expression is “all models are wrong (but some useful).”[1]

In this chapter, we build on the map metaphor to argue that having more than one map is important for expanding our possibilities of thought, and thus practice, in relation to health psychology. We start with mainstream psychology and its engagement with the biopsychosocial approach below (also see Morison & Gibson Chapter 2.1 for discussion of the biopsychosocial approach in relation to understanding health and illness).

The biopsychosocial approach

We start with the biopsychosocial approach[2] because it is foundational for health psychology (Crossley, 2008). This approach to thinking about people’s health can be traced to an article by American psychiatrist George Engel (Engel, 1977). Engel proposed a model of health, within which the range of factors interacting to shape health behaviours and outcomes could be classified into one of three categories related to a person’s biology, psychology, or social context, the latter including social, cultural, and environmental factors. The three elements of the biopsychosocial approach are understood as existing independently from each other, but interacting in complex ways. See text box below using coronary heart disease as an example.

Example of some of the biopsychosocial elements related to coronary heart disease

Cardiovascular diseases, which include coronary heart disease (CHD), are a leading cause of illness and death worldwide (World Health Organization, 2021). A range of factors influence health behaviours and outcomes for CHD (Steptoe & La Marca, 2022). Biological, psychological and social examples include:

Biology: genetic predisposition can account for between 40 – 60% of variance of risk (McPherson & Tybjaerg-Hansen, 2016).

Psychology: people’s response to stress impacts CHD. Fun fact: the concept of a Type A personality came from a cardiologist whose patients were wearing away chair upholstery in a pattern that suggested they were agitated while waiting (Friedman & Rosenman, 1974).

Social: racism and childhood trauma are both implicated in the development of CHD through stress-related physiological responses (Almuwaqqat et al., 2021; Javed et al., 2022; Su et al., 2015); while social norms and government policies can reduce smoking (Monson & Arsenault, 2017; Rey Brandariz et al., 2024).

Interaction: an epigenetic study of people who had experienced periods of starvation during World War II in Amsterdam showed that their children experienced genetic changes that predisposed them to develop CHD (Roseboom, 2019).

The biopsychosocial approach helps us think about how our health is produced through intersecting elements (biological, psychological, and social), which in turn, helps health professionals develop efficacious health interventions to support recovery or prevent illness. Continuing our CHD example, breathing techniques to reduce stress responses work on the biological level; providing information on diet addresses the psychological (cognitive) level; and providing collective exercise classes speaks to social issues (e.g., social support). These are all designed to have subsequent positive effects on the biological (e.g., reducing development of disease).

Interventions can also be developed from recognising how different biopsychosocial levels intersect with each other. For example, social isolation and loneliness are psycho-social risk factors for CHD (Kahl et al., 2023). Recognising the dynamic relationships between the biological, psychological, and social also alerts us to how onset of disease (biological) can cause psychological and social outcomes. For example, the experience of illness creates stress (psychological) and affects people socially (e.g., loss of job or isolation) (Barlow et al., 2015).

For health psychology, the advantage of the biopsychosocial approach is that it gives psychology a role alongside the medical profession, and it recognises human health as a complex system. As such, the biopsychosocial approach encourages us to think of illness as having multiple, interacting factors, rather than single causes. This creates richness in our understanding, thus increasing the likelihood of more efficacious interventions.

Problems with the biopsychosocial approach

However, there are concerns from both critical and mainstream health psychologists with how health psychologists and other health practitioners use the biopsychosocial approach. As we discuss below, these problems relate to:

- poor theorising and a lack of explanatory power

- one element getting priority

- an individualist approach.

a) Theorising the biopsychosocial approach

When Engel (1977) coined the term “biopsychosocial”, his primary focus was critiquing biomedicine as dehumanising because it was:

- reductionist (reducing complex phenomena to a single primary issue), in this case, the biological

- underpinned by a mind-body dualism that gave no role for the mind in disease causation or progress

- imagining the body like a machine, with atomised parts that could be isolated from the whole to be removed or fixed.

Instead, Engel wanted hospital care to include considerations of:

…the person who has the illness, the person’s experience of, account of and attitude towards the illness; whether the person or others in fact regard the condition as an illness; care of the patient as a person … the effect of conditions of living on onset, presentation and course; and finally, the healthcare system itself … [which] involves social factors such as professionalisation (1977, p. 131–135).

Engel drew all of that together in the pithy term “biopsychosocial”, seeking to encourage a holistic approach to healthcare. But he did not theorise how the bio-psycho-social elements might causally affect each other, nor suggest how to align the psychoanalytic approach of the psychology of the time with the biomedical focus on physiology (Bolton & Gillett, 2019).

Researchers were thus left without direction for how they might operationalise the biopsychosocial model to give it explanatory power (Roberts, 2023). Some ultimately concluding that it was “a slogan too vague to be of any use” (Bolton & Gillett, 2019, p. 6; referencing a critique by Ghaemi, 2009) or that it was never designed to be treated as an explanatory model in the way that people have subsequently—and erroneously—tried to use it (McLaren, 2021). These problems, of (1) explanatory power and (2) untheorised causal relationships, continue to haunt health psychology, with Stam’s (2000) critique generally holding, 25 years later:

It is an interesting phenomenon in its own right that such a loose formulation has become the rhetorical mainstay of theory in health psychology … it appeared almost obligatory to mention the model although very few contemporary textbooks cite papers beyond the original formulations by Engel (1977) or the revision published by Schwartz in 1982. The ‘model’ has simply been taken for granted and, remarkably, there is absolutely no discussion of what this term could mean other than the ‘interplay’ or ‘interaction’ of biological, psychological and social factors (Stam, 2000, p. 24).

b) One element gets priority

Without clearly conceptualising the relationships between the biological, psychological, and social, one element can get emphasised over the others, such as when a dominant conceptual framing shapes researchers’ perspective (Roberts, 2023). For example, a biomedical orientation can produce a “bio bio bio” focus, conflating the biopsychosocial model with the biomedical model (Mescouto et al., 2022). This can be seen when mental health problems like psychosis are framed primarily as a (biological) chemical imbalance, which precludes discussion of how psychosis might be understood as a psychological solution to social difficulties (Baboulene, 2020). (See Harper & Cromby (2013) for a similar argument on paranoia).

Conversely, a culturally dominant framing can emphasise psychology, such as when noncommunicable diseases, like coronary heart disease, are framed as “lifestyle diseases” and the outcome of poor decision making. This “psycho psycho psycho” approach undermines and blames patients, negating the biological and social elements of disease causation (Robson et al., 2025). At other times, two, but not three of the elements are considered by researchers professing to use the biopsychosocial model. For example, In their evaluation of how physiotherapist literature on lower back pain enacted the biopsychosocial model, Mescouto et al., (2022, p. 3270) stated that the “social context was rarely mentioned … and other broader aspects … such as culture and power dynamics received a little attention.”

c) Aligning the psychosocial to a universalising, atomised and individualist approach

Distancing itself from psychoanalytic theory, mainstream psychology became dominated by the natural science paradigm, which aligned more easily with the biomedical approach, since the researcher was understood as being able to observe an external world objectively, and produce generalisable findings that could be applied to a range of populations or contexts. From this, the job of psychologists working in health was to develop the “psycho” and/or “psycho-social” part of the model through empirical research that aimed to identify universal psychological variables implicated in health behaviour.

These variables were conceptualised as interacting, but discrete, atomised components. They also needed to be measurable so that they could be comparable with biomedical measures and included in statistical analysis and modelling (Crossley, 2008). The outcome was a psychological project of substantial and sophisticated analysis focused on developing socio-cognitive models comprised of atomised elements with hypothesised relationships, and the quantifying of subjective experience through the development of scales to measure them (Ogden, 2003).

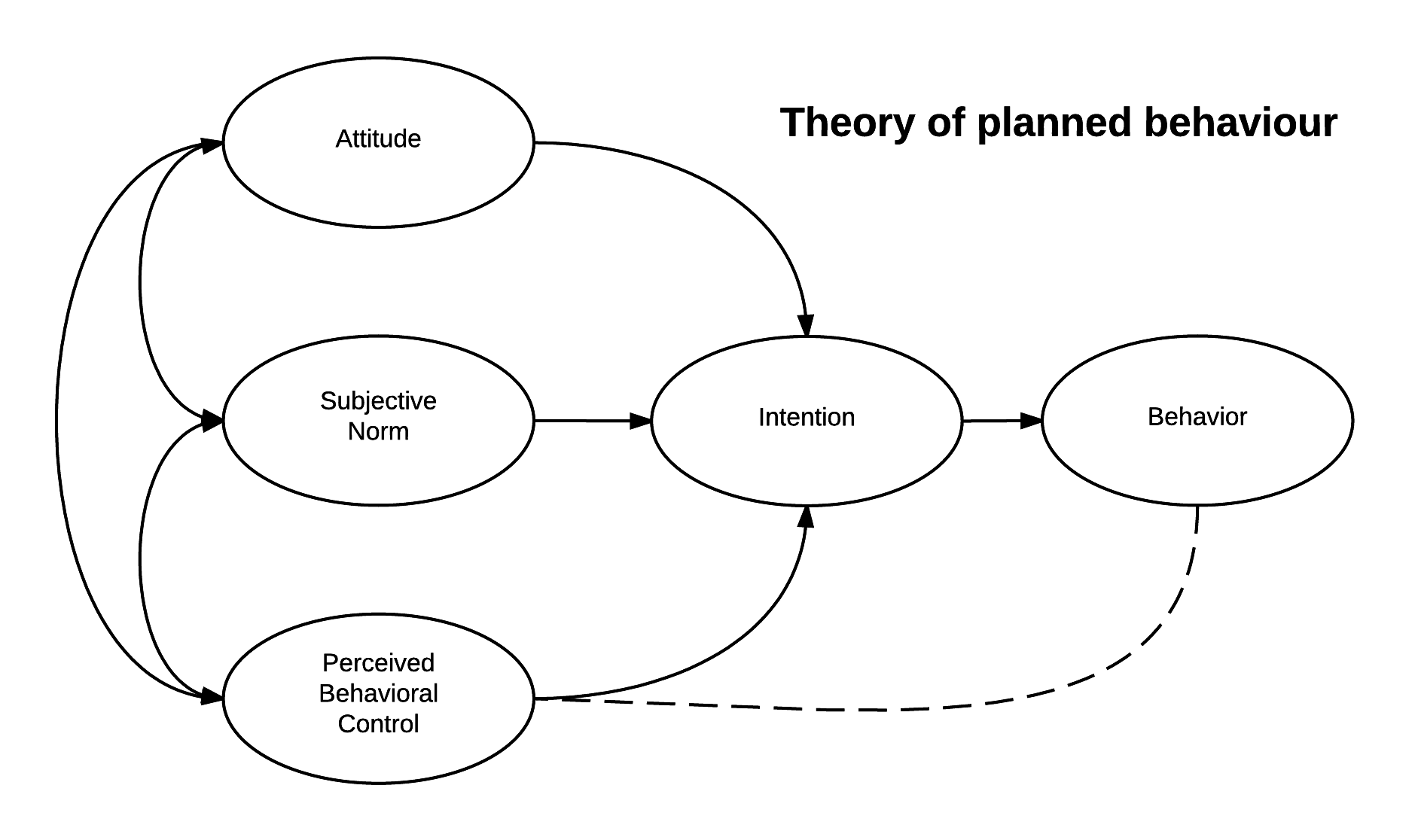

An example of a socio-cognitive model is the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB). The TPB has three elements (attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control) that are hypothesised to predict intention to behave, and thus behaviour (Ajzen, 1985; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1972).

TPB is a significant model. A Google Scholar search at time of writing, gives nearly two million results for research articles with “theory of planned behaviour” in the title, and review studies show it is one of the most successful models psychologists have for predicting variance in health behaviours (Mielewczyk & Willig, 2007). The TPB can account for between 4–50% of behaviour variance depending on the health behaviour studied, if TPB was supplemented with additional measured variables, or whether objective measures of behaviour were used in the study (Armitage & Conner, 2001; Mielewczyk & Willig, 2007). Meta-analyses of TPB research suggest “small-to-medium-sized effects, albeit with considerable between-study heterogeneity” (Hagger & Hamilton, 2024, p. 201).

Overall, the evidence suggests that TPB—and relatedly, the Health Belief, Reasoned Action, and Trans Theoretical/Stages of change, to name all four main social cognition models—may be useful tools in health psychology for understanding some health issues, in some contexts. But, overall these models have “poor showing in predicting behaviour” (Stainton-Rogers, 2017, p.46). Returning to our map metaphor, social cognition models, such as TPB, leave a lot of the territory unrepresented. As, Mielewczyk and Willig (2007) argue, “given that TPB routinely leaves around four-fifths unaccounted for … we need to develop theories which are far more able … to address the variety and complexity of the influences and processes involved in the performance of health behaviours” (pp. 82, 817).

Of particular interest for us, given the critical health psychology pou of moving beyond individualism, and considering knowledge as produced in context, is the limited way in which the social context is conceptualised. These include how TPB, and more broadly the socio cognitive models it is part of:

- fail to include factors that can predict health behaviour without changing intention to behave, such as when nudging (changing the choice architecture) changes people’s health behaviour (Sniehotta et al., 2014)

- do not adequately account for the dynamic nature of social contexts, nor includes researchers’ reflection of their own cultural location and context (Ogden, 2015)

- take an individual focus, which has limited effectiveness in practice because this minimises the important role of the social determinants of health (e.g., Theis & White, 2021). For example, in the TPB, all the complexities of wider social, governmental, environmental, and relational contexts in which health related behaviours are practiced are reduced to considerations of perceived subjective norms and perceived behavioural control (both of which are conceptually located in the individual). For further discussion, see Rosin et al., (2024) and the NICE evidence review of behaviour change interventions, which evaluated psychological behaviour change research and recommends developing interventions that “take account of the social, environmental and economic context of behaviours” (2007, p. 56).

In summary, mainstream health psychology is now conceptually aligned with biomedicine through the use of social-cognition models, providing opportunities to have a shared theoretical framework for a biopsychosocial approach. However, many researchers and practitioners have raised concerns that this shared framework is flawed in how it:

- conceptualises people in individualist and universalising ways, and,

- reduces psychology to atomised and measurable parts.

We develop these concerns below in relation to how this overall approach can lead to:

- reification – treating concepts as if they are real

- oversimplification of complex experiences

- epistemic injustice – treating people’s realities as wrong

- under theorising of power.

a) Reification: As a student, Sarah had an existential crisis when it occurred to her that the model she was experimentally testing was not made of “real” elements, but social constructs being treated as real. It was rather a comfort to find out that a similar crisis had sent Kenneth Gergen on the path to laying the foundations of social constructionism in psychology (Gergen, 1996). Reification occurs when psychologists treat the psychological elements in a model or scale as if they are real, confusing the map with the territory.

b) Oversimplification: The models used in this kind of psychology are atomistic (separating out elements) and universalising (since they seek generalisable, not context-specific knowledge). This can oversimplify the complex dynamics that underpin human (health) behaviour because it misses how health practices are contextualised and relational. For example, depending on context and interpersonal relations, expecting condom use during sex may signify trust in taking care of your partner’s sexual health, or a distrust in your partner’s monogamy (Willig, 1995).

Indigenous scholars have also problematised atomisation in quantified psychological measures. For example, King et al. (2017) argues that mainstream constructs of atomised, measurable psychological categorisations is a product of European industrialisation, urbanisation, and a particular strand of philosophy that has reduced complex phenomena to measurable categories that fail to recognise the contextualised, interconnectedness, fluidness, and heterogeneity of the self. The authors argue that the outcome for psychology is an “impoverishing psychological knowledge of the self” (King et al., 2017, p.728). Writing from a Māori perspective of studying epistemology in psychology, one of the authors (Pita King) explains,

…one of the first things I … noticed when studying European philosophy was its eagerness to distinguish, categorize, order, and in general, to break things apart and to pin down their definitions with a high degree of “certainty.” … For Māori, less importance is placed on atomizing the subject matter under consideration. Atomization is often avoided (King et al., 2017, p. 731).

c) Epistemic injustice: describes when “someone is wronged specifically in their capacity as a knower”, either by having their credibility unfairly undermined due to prejudices, or by underrepresentation of marginalised groups in collective knowledge making (Fricker, 2007, p. 1). It can apply to “medical gaslighting”, but we connect it here to the way that psychological measures reduce the complexity of human experience and decision making in ways that feel harmful. Crossley (2008) gives an example when describing how a research participant who she was interviewing, expressed anger at the safe sex messaging of health professionals and the sense of judgement she felt for having unprotected sex with her (HIV positive) partner. The participant explained that she did not care about the risks, not because she did not know them, or was sentimental, emotional, or foolish, but because:

It’s so much more than that. I can’t really express it. It’s just so incredibly important. A kind of moral stance, if you like. To say, look, there are higher values in this world than just ‘keeping safe’. To show him how I value him over and above all the trite messages that we’re bombarded with (p. 24).

Crossley (2008) reflects that health psychology models might categorise this woman as low in “perceived benefits“ of safe sex, but to do so would be to undermine what she had said about complexity. The use of socio-cognitive models in mainstream psychology can therefore produce epistemic injustice. As Crossley (2008) argues,

…mainstream health psychology seems to have largely bypassed a consideration of many of the complex moral, emotional and ethical issues that lay at the very heart of peoples’ experiences of health and illness. It has done this through the use of methods that encourage reductionism and the objectification of experiences into simplistic coding devices that facilitate the testing of particular theories and models (p. 26).

d) Under theorising of power: Power issues tend to be minimised when psychologists think about the ‘social’ element of the biopsychosocial model. Health psychology textbooks might include issues such as class or ethnicity, for example, but not connect these to exploitative capitalism or structural racism to understand how they come to matter. For example, in a book translating health psychology research into practical guidance for people working with clients, social practices are mentioned, but not racism (Kwasnicka et al., 2021).

Similarly, the Behaviour Change Wheel (Michie et al., 2011) includes social and physical opportunities as elements that can limit health behaviours, but directs focus back onto the individual. This is seen in suggestions of interventions related to education, persuasion, incentivisation, and even coercion, all of which focus on the individual as the site of change (Marks, 2020). This focus on the individual leaves power and social structures under theorised in our models, thus potentially missing important elements that shape people’s health experiences. In relation to CHD, such arguments have led critical health psychologists to ask if this is why less than 50% of patients diagnosed with CHD complete cardiac rehabilitation or maintain rehab-taught lifestyle changes to diet and exercise at six-month follow-up (Robson et al., 2024).

Section summary: The biopsychosocial approach aligns psychology with biomedicine by focusing on identifying discrete variables in cause-and-effect relationships. This approach can predict some variance in behaviour, providing directions for how to develop efficacious interventions. However, it fails to deal with the complexity of lived experience, sometimes causing harm through epistemic injustice. For these reasons, some psychologists have put this conceptual map down, and explored the possibilities offered by phenomenology.

Phenomenological health psychology

Much of mainstream health psychology continues to conceptualise its job as identifying discrete, compartmentalised, and measurable elements that are valued if they can predict enough variance of behaviour across large groups of people. This “nomothetic” approach stands in contrast to phenomenological psychology, which takes an “idiographic” approach that prioritises a deep dive into individual, lived experiences of people as they understand and experience them. As such, phenomenologically informed psychology (herein “phenomenological psychology”) speaks to the concerns of oversimplification and epistemic injustice discussed above.

Phenomenology is a branch of philosophy developed in the work of people such as Husserl, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, Sartre and Stein. These people were European philosophers writing in the early and mid 20th Century, although they also drew on ideas with a longer history,[3] and their ideas were subsequently developed by others (e.g., Ricoeur and Schutz). This means that phenomenology is an umbrella term for a range of ideas, some of which are conflicting.

Conflict also emerges when psychologists use phenomenology, since taking thinking from one discipline and applying it in the service of another inevitably creates translation issues and disagreements. What phenomenological psychologists share, though, is a model of the person as an interpreter, who is constantly making sense of their conscious experiences. The word “phenomenon” is derived from the Greek for “show” or “appear”, with “phenomenology” being the study of how things appear to people.

Conceptualising the person as an interpreter is linked to Husserl’s response to Descartes’ famous statement “I think therefore I am”. Husserl argued that, if a person is thinking, they need to be thinking of something, therefore when we are conscious, we are conscious of something (Husserl, 1901/1970; cited in Eberle, 2022). This argument gives us the phenomenological concept of “intentionality” of consciousness. Eberle’s (2022) gives a helpful example of perceiving a bird: he is not objectively perceiving a thing external to him, nor a conceptual concept of a bird, but the bird as it is perceived by him in that moment.

Phenomenologists reject the idea that researchers can stand outside of the world to observe it (as in the natural sciences paradigm described above). Instead, they collapse distinctions between the subject (who is studying) and the object (being studied). As Eberle explains, “Husserl argues that the crisis of modern sciences was caused by the fact that they had taken their idealizations and abstractions, their mathematical and geometrical formulae, for bare truth and had forgotten that they originated in the life-world” (2022, p. 110; also see reification argument above). From the perspective of phenomenological psychologists, psychologists’ should prioritise understanding that life-world, that is, how a phenomenon is subjectively perceived, experienced, and interpreted by a person (Langridge, 2007).

For these psychologists, phenomenology is the “study of human experience and the way in which things are perceived as they appear to consciousness” (Langdridge, 2007, p. 10). It is underpinned by a model of the person as an individual, actively perceiving, experiencing, and interpreting their “lifeworld”. This model of the person is individualised, since people’s thoughts are framed as originating from a relatively coherent self that is the author of their own meaning-making and interpretation of their experience.

Although the focus is on the individual, a person’s interpretation of their lifeworld is understood to be highly contextualised because this model of the person is of “a situated, meaning-making person” (Larkin et al., 2011, p. 318). In this conceptual framework, people cannot stand outside of their world. Instead, interpretation of the present moment is shaped by:

- the interpretive frameworks that people have already developed through past experiences

- the linguistic concepts they have available

- intersubjectivity, as meaning making is generated between people (e.g., awareness of other people’s feelings about an issue can shape interpretations of an experience)

- embodiment, since people are conscious of the world through their bodies (Eberle’s experience of a bird is shaped, for example, by the kind of eyes and visual cortex that he has as a human).

- emotions, since these “color” how people experience a phenomenon (Russell, 2006, p. 68).

- temporality, since experiences occur in a particular time (and place), in an ongoing way, and experiences of the past can also shape interpretation of the present moment.

In Notes from a Heart Attack: A Phenomenology of an Altered Body, Kevin Aho provides a personal reflection on his experience of suffering a heart attack at 48 years old. He uses phenomenology to explore how such a “world-shattering” (Aho et al., 2019, p. 189) event altered his lived experience of the body, touching on key elements such as embodiment, temporality, spatiality, affect, and intersubjectivity.

Embodiment: Aho describes how his sense of embodiment was radically altered by the heart attack: “The ‘I can’ that opened up my world, that I had effortlessly embodied just a few weeks earlier, had become a debilitating ‘I can’t'” (p. 192). Before the heart attack, he took for granted the possibilities his body afforded him, such as planning long bike rides, overseas travel, and a productive career in academia. After the heart attack, his body became a source of vulnerability and uncertainty, an intimate site of heightened awareness. It also came under the gaze of healthcare professionals as a detached, corporeal object.

Temporality: Aho describes how time became more fragile with his increased consciousness of mortality. His ability to plan or envision long-term goals was hampered by the constant awareness of his body’s vulnerability; what if his implanted defibrillator shocked him while he was travelling? While he had once lived a fast-paced life, he was forced to slow down and reflect on the identity he previously held—the productive, active and dynamic professor—and reshape a new identity, all while navigating a constant feeling of trepidation and uncertainty about the future.

Spatiality: Aho’s describes feeling like his altered, broken body was taking up (too much) space, while simultaneously feeling that his world was contracting: the four yellow footsteps painted on the hospital floor encouraging him to walk as far as the bathroom; the university campus and his neighbourhood became threatening, expansive spaces. The heart attack collapsed his world, reducing it to the confines of “safe” spaces.

Affect: Aho experienced fear, vulnerability, and anxiety, as well as the bodily effects of medication, including fatigue, which impacted his ability to work and socialise. Most frightening to Aho was that the things that used to give him pleasure, such as movies, food, and reading, he now experienced as “affectively empty and flat” (p. 194). These hobbies and activities that held his identity together became meaningless, resulting in a “bleached” life, an inability to feel affected, and a crisis in identity (p. 194).

Intersubjectivity: The heart attack also brought about a new kind of intersubjectivity; Aho became vulnerable, and dependent on the expertise and care of others. His previously held illusion of autonomy and strength was fractured. Aho recalls an altercation with a cardiologist, who flippantly told him, “It may require surgery, but who knows?”, to which he replied, “You should know! You’re the damn doctor” (Aho, 2019, p. 194). Although strained interactions with healthcare professionals were common, the heart attack experience also introduced new dynamics of care, trust, and vulnerability. He experienced gratitude and connection during recovery, with the support of nursing staff and loved ones helping him make sense of his newly altered body and identity. For example, he described being overcome with love and appreciation not just for his family, but also for strangers, in recognition of his, and everybody’s, helplessness and dependence on others.

Applied to research, phenomenological psychology conceptualises both participants and researchers as interpretive beings. Research encounters thus form a “double hermeneutic”, of participants interpreting their experiences, and researchers interpreting that interpretation (Smith, 2007). This opens the possibility for psychologists to analyse beyond what people say or might be aware of. Relatedly, phenomenologists might draw on other theoretical frameworks to help with their interpretation (Langridge, 2007), including psychoanalytic theories (to explore what might be unconsciously driving experience), or social theories (to examine how social structures related to class, gender, sexuality and dis/ability, shape experience).

However, as Guenther, (2020, p. 12) argues, “structures like patriarchy, white supremacy, and heteronormativity … [are] … not things to be seen but rather ways of seeing, and even ways of making the world that go unnoticed without a sustained practice of critical reflection” (their emphasis). The risk for phenomenological psychology, then, is that in focusing on understanding people’s lived experience, people working within this approach have not attended to the social structures that shape experience because neither the participant, nor the psychologist, considered such issues in their interpretation.

A way to address this problem is to take a critical phenomenological approach that seeks to connect people’s lived experience to wider social structures. However, this critical orientation is most conceptually aligned with phenomenology when it is done with research participants who include social structures as part of their interpretation. For example, Ahmed’s (2014), phenomenological analysis considered how equal rights activist Audre Lorde experienced being made a racialised subject when treated as vermin as a young Black girl on a New York train: “Suddenly I realise there is nothing crawling up the seat between us; it is me she doesn’t want her coat to touch … I will never forget it … The hate” (Lorde, 1984, p. 148).

Section summary: Phenomenology offers a theoretically rich approach to studying the complexity of lived experience of health, including how lived experience is contextualised in time, space and embodiment. It is possible to do critical phenomenology in psychology, but few phenomenological psychologists have engaged with political or social structural analysis. Phenomenological psychology therefore remains individualist, offering a limited map for psychologists interested in issues of power. For these reasons, critical health psychologists often prefer a social constructionist approach.

Social constructionism

Although mainstream health psychology (epitomised in the biopsychosocial approach) and phenomenological psychology are distinct approaches, both share an individualistic orientation to thinking about the person. Social cognition models, for example, are underpinned by taken-for-granted individualist ideas of the person as a separate being, who then interacts with their world and other people. For example, questions about how concerned people are about meeting social norms in TPB studies imply that people are separate from social norms ontologically, even if they rate themselves as caring very much about meeting them.

Thus, while models in mainstream health psychology are often revised, as researchers investigate, debate, and develop them, psychologists rarely question the assumed individualism behind these models. The idea of a separate, rational, coherent, autonomous being who interacts with others, and their environment, therefore remains unchallenged. Relatedly, phenomenology also focuses on the individual, despite blurring distinctions between the subject and the object.

In much of psychology, there is the assumption that the self is coherent and stable enough that, with the right scientific tools and rigour, researchers can identify its real nature. This assumes that the focus of psychological research is the individual, conceptualized as an independent entity, albeit one that develops as they interact with others in society (Riley et al., 2021, p. 286).

In Western thought, individualism is such a taken-for-granted way to understand people that it is often confused with the territory. We gain this insight particularly from cross-cultural analysis, as anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1974, p. 31) infamously stated:

The Western conception of the person as a bounded, unique, more or less integrated motivational and cognitive universe; a dynamic center of awareness, emotion, judgment, and action organized into a distinctive whole and set contrastively both against other such wholes and against a social and natural background is, however incorrigible it may seem to us, a rather peculiar idea within the context of the world’s cultures.

When Geertz wrote this, the “us” he was referring to were Westerners, grounded in North American and European traditions in thinking. In contrast, as Kora and Brittain (see Chapter 1.1) have highlighted, those who are steeped in a te ao Māori worldview would argue that the individualism of Western concepts of the self is the peculiar idea.

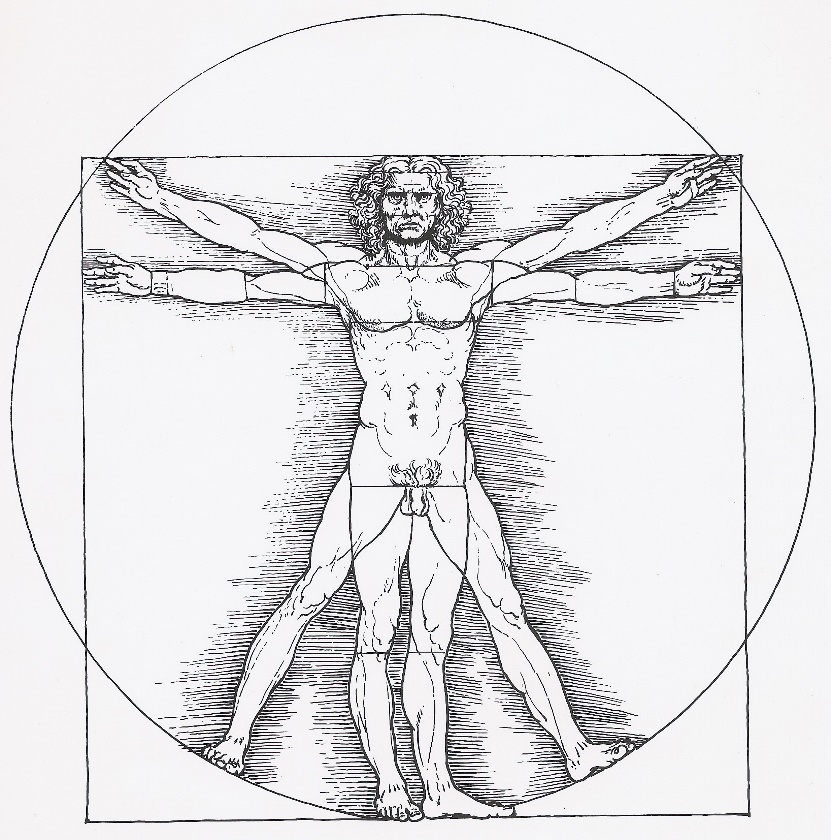

Leonardo DaVinci’s Vitruvian man (see Figure 1.2.2) offers us a representation of this individualism. The image places an individual human at the centre. The person is male, adult, seemingly without dependents, and not currently dependent on others, since he is represented as separate from other people and from his environment. The ideal healthy human represented in this image is thus a separate individual, autonomous, fully formed, and in a stable state of health.

There are several concerns with such representation standing in for ideals of health. For example, many people find vitality in experiences that could be described as the opposite of autonomous independence, such as when distinctions between self and other are blurred in intimacy, playing sports, being in an audience, or in spiritual experiences that transcend the self. Pregnancy also creates dynamic and deeply interdependent embodied experiences that contrast with ideals of an autonomous, stable body. Relatedly, the Vitruvian man is male and European, which when represented as an idealised norm, reproduces Eurocentrism, colonialism and the male-as-norm (Coulthard, 2014; Ussher, 2006).

As a figure who stands in for ideal humanity, Vitruvian man represents a cultural norm that is not attainable for most people, since everyone is born dependent, and most of people will experience fluctuating levels of sickness, dis/ability and/or dependency across their lifespan. The Vitruvian man thus reproduces “our collective fantasy that the body is stable, predictable, or controllable” (Garland‐Thomson, 2011, p. 603). As critical disability scholars have argued, this “mythical norm” pushes many people outside of constructs of valued humanity, creating and problematising people who “misfit” (Garland-Thomson, 2011). These norms “haunt the human sciences by establishing and re-inscribing norms and outliers, ensuring that some of us are more human than others, and that many of us are excluded from the category” (Rice et al., 2021, p. 98).

Social constructionist theory

Social constructionism shifts analytic focus away from the individual, and onto the shared, social constructs (or ideas) that circulate between people. Social constructionism is an umbrella term covering a range of theories that share the idea that what we consider to be “facts” about the world are, instead, culturally shared agreements about reality. In other words, our truths are shared understandings that are “taken-for-granted” by people in a particular time and place.

This idea is supported by cross cultural and historical analyses that show significant differences in how people make sense of themselves (see Geertz, 1974, quote above). For example, today, English people would usually point to their heart if asked where they feel love. But, in Shakespearean England, the liver elicited passionate feelings (Riva et al., 2011): “Then shall he mourne, if ever love had interest in his liver” (Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, 1600 ca.; cited in Riva et al., 2011, p. 5).

Social constructionists argue that if human understandings were driven by the natural world, they would mirror a shared external reality across both time and cultures and therefore there would be little variation in our sense making (Burr, 2025). To use our example above, people could be heartbroken or liverbroken, but not both. Given that people have been both, it is therefore likely that the ideas humans have to make sense of their world are socially produced and historically bound.[4]

Further, these ideas are communicated and shared through language. To continue our example, Shakespeare grew up in a world where people talked and wrote about emotions as emanating from their liver, providing a conceptual framework for understanding the liver as a source of feelings and emotions. Social constructionists therefore highlight the importance of language because they do not see it as neutrally describing the world, but rather as actively constructing it. Social constructionists would therefore argue that the reason why it is hard for those of us who are English (only) speakers to imagine feeling love in our liver—or even find the idea ludicrous—is because we have not grown up in a linguistic community that makes connections between that organ and our feelings. We do not have a language for it, thus the liver is excluded from our culturally shared agreements and communication about embodied feelings. Also see below for “How language shapes the way we think” video (Boroditsky, 2017).

From a social constructionist perspective, language enables possibilities for thinking because it provides the building blocks for thought. This argument flips a common sense idea that thoughts originate in people’s heads first, and then, if we want to communicate them, we convert them into words or other forms of expression. Instead, social constructionism argues that language has a prior existence before us, offering us a set of concepts from which we can build our individual thoughts. An analogy might help here: two children playing with Lego could build very different Lego creations, but those creations are produced with block-like shapes, and whatever they make, it will not look like something they made with stickle bricks. As the philosopher Wittgenstein said, “the limits of my language … mean the limits of my world” (1961, p. 68).

Activity

If people cannot think outside of the concepts they have available to them, then they are “constituted through language”, because language provides the conceptual building blocks for them to make sense of themselves. This argument is often counter to our taken-for-granted understandings, so an activity might help:

Two sites that circulate ideas for thinking about our bodies are social media and sports. For example, social media circulate ideas about a “glow” while sports can talk about “low centre of gravity”. Now think of a concept or phrase that is familiar in your social media or sports world that is used to describe the body, and imagine looking in the mirror:

-

- How did you think about your body before you knew that concept/phrase?

- Once you were familiar with that concept/phrase, how did you think about your body?

- Even when not looking in the mirror, do you ever use that concept/phrase to think about your body? And, if you do, does it elicit good or bad feelings about your body, or about yourself, or other people?

The above activity is intended to help you understand how concepts – including those we use to make sense of ourselves – circulate outside of ourselves first, and once we become familiar with them, can become concepts we use to think with and take for granted. Once we start to use these ideas to think with, they feel like they originate in us, as our own ideas because they are in our personal thoughts. And because we experience these ideas as our own thoughts and beliefs, it is hard to think differently even when we want to. For example, people critical of media representations of the “thin-ideal” can find it frustrating that they still want to be thin. Further, knowledge and action go together (Burr, 2025; Gergen, 1985), so social constructions shape, not just what people can think, but what they can say, feel or do. (We will unpack relations of power and language further in Riley et al. Chapter 1.4).

Key takeaways: The social constructionist model of the person

- people are born into a world where concepts for how the world can be understood are already circulating, primarily through language

- as people grow up, they learn to understand the world—including themselves—through these concepts

- these concepts can differ across socio-historic contexts

- people are thus constituted through their social context

- the social constructs available to a person shape what they can say, think, feel or do.

Social constructionism offers a radical alternative to the individualism of mainstream psychology and phenomenological psychology, by shifting focus onto what concepts for meaning making are shared within a particular socio-historic context. Social constructionism thus “de-centres” the subject in psychology, moving focus away from the subject and onto language.

As well as recognising differences in meaning making across socio-historic contexts, social constructionists also argue that there is variation within socio-historic contexts. Thus, in any given socio-historic context, different ways of making sense of an issue circulate, potentially offering multiple ways for people to make sense of themselves (Billig et al., 1988). Social constructionist psychologists are therefore often interested in the different ways people make sense of themselves.

The multiplicity of everyday sense making

Robson et al. (2024) offers a novel approach to explore the perennial problem of why patients do not follow doctors’ advice, showing how doctor’s expert medical knowledge could be constructed in multiple ways that simultaneously made it valued and devalued. Here is an example from a participant discussing how he feels about his prescribed medication:

…you have to listen to the advice of people who, you know, hopefully know more than you do, you know, and I listen to my GP and I’ve listened to the consultants, at least I’ve got from 80 mgs down to 40. Who knows, maybe with diet, now that I’ve got the stent in, eventually maybe I’ll be able to kick them in the head completely (Eddie, mid 60s, retired public service worker living in Wales, UK; cited in Robson, et al., 2024, p. 11).

We identify three social constructs in Eddie’s extract: (1) medical advice to take medication has value; (2) medication-free life is preferable; and (3) a language of addiction where people aspire to be free of drugs (“I’ll be able to kick them in the head completely”). Moved through fluidly during a few seconds of speech, these accounts are partially contradictory (e.g., medicine is both valued and devalued), and draw on wider discourses, including those that position medical doctors as expert specialists, and the current resurgence towards framing natural as inherently good and medicine as bad (Greenhalgh & Wessely, 2004; Robson et al., 2024).

Within social constructionism, people are therefore not theorised as unified, relatively coherent, bounded individuals as we are used to in Western thinking. Instead, social constructionism:

…replaces the self-contained, pre-social and unitary individual [of individualist psychology] with a fragmented and changing, socially produced phenomenon, who comes into existence and is maintained not inside the skull but in social life (Burr, 2015, p. 122).

The outcome is that people are conceptualised as multiple, contradictory, fluid, and partial, because they are constituted within multiple, contradictory, and partial forms of sense making (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2017). We expand on these points below:

- Constituted: people can only draw on the linguistic concepts that are available to them. Although they may actively use, re-appropriate, resist, or otherwise negotiate these conceptual ideas, they cannot think outside of them. For example, Crossley’s participant could push back against safe sex messaging, but she struggled to articulate another way to be understood. Her “I can’t explain it” suggests that she was unable to access another way to make sense of her experience.

- Multiple: people have access to different ways to make sense of themselves, others, and issues in their world, as in the example of genetics versus lifestyle explanations of disease causation we gave earlier.

- Contradictory: given the multiplicity of sense-making circulating at any one time, some social constructs will contradict others. This means people may understand themselves in conflicting ways. Social constructionist approaches do not problematise such contradiction because it is seen as the outcome of people shifting between multiple meanings, rather than a failure to produce a coherent self or to reconcile the accuracy of contradictory information (as individualist approaches might conceptualise it).

- Fluid: people may dynamically move through different forms of meaning making, both over the course of their day, and lifetime. A person with coronary heart disease may, for example, shift between understanding themselves as a loving partner, a good patient, and an organised person, as they, respectively, kiss their partner goodbye in the morning, visit their doctor for a check-up, and plan their diary.

- Partial: people may only be partially constituted through specific forms of sense-making, because they:

- draw on concepts in a fleeting way, producing only partially formed thoughts

- may not be fully aware of the underpinning rationality of these concepts (in the same way that Western psychologists might not notice the individualism underpinning their ideas)

- need another person to confirm that sense-making. For example, Crossley validated her participant by listening to her.

Psychological language

We take psychological language for granted. We use it all the time, such as when we encourage people to have a positive attitude, describe ourselves as “a bit OCD”, or list our strengths and weaknesses for a job application in ways that make even our weaknesses sound good (“my perfectionist tendencies mean I do every job to the highest level”). Often such talk reproduces an understanding of a unique, autonomous self that we can find by looking “inwards”.

It is hard to imagine how we might make sense of ourselves without psychological vocabularies (Rose, 1998). People who are not good at doing so are often problematised, since they are unable to reflect on their thoughts and feelings, and develop better self-awareness (Illouz, 2008).[5]

Psychological language is a taken-for-granted in our current socio-historic moment, so it might be a surprise to know that it is a relatively new phenomenon, and the outcome of multiple social processes, including:

- developments during the European Middle Ages as people imitated new royal court practices of etiquette that required an ability to keep some emotions private/hidden, when previously, emotions were public displays (Elias, 2000)

- later shifts from monarchy to democracies, requiring governments to have self-regulating citizens who would primarily govern themselves within valued constructs of citizenship, rather than as subjects of authoritarian monarchical rule (Foucault, 1977; Gibson, 2016; Miller & Rose, 1990; also see Riley et al. Chapter 1.4 for discussion of “governmentality” )

- 20th Century rise of therapeutic cultures, built on developments in medicine, psychiatry and psychology (Foucault, 1976; Parker, 2015), including psychoanalysis and humanism (Illouz, 2008) and 21st Century self-help cultures (Riley et al., 2019a; Riley et al., 2019b) that require an inward focus to facilitate “fixing” the self

- 20-21st Century expansion of neoliberal economics that has required autonomous, rational, flexible, and risk managing citizens to meet the needs of a market-driven economy (Harvey, 2005; see Riley et al. Chapter 1.4 for further discussion on neoliberalism)

- 20-21st Century digital technologies requiring people to participate in significant reflection on how they present themselves to others (Gergen, 1991; Orgad & Gill, 2021).

More-than-human theory

Social constructionism offers a substantial critique and alternative to individualism, locates knowledge in its social context, and opens possibilities to embed theorising power (especially when connected to poststructuralist theories of power, which we explain in Riley et al. Chapter 1.4). Social constructionism therefore speaks to several of the pou of critical health psychology. However, the focus on social constructions at the expense of material aspects of the physical world, has led some critical health psychologists to turn to “more-than-human theory”.

More-than-human theory is informed by the work of Deleuze and Guattari (e.g., 1987), Braidottii (e.g, 2013), and others, including Barad’s (2007) argument based on quantum physics, that you can study the real, even though the real changes in response to being studied (Barad, 2007). We unpack these arguments further in Riley et al. Chapter 1.3. For now, what is important to know is that more-than-human theory emphasises the mutually co-constitutive processes in which meaning-making and the physical world (“materiality”) dynamically interact. That is, the human and nonhuman produce and shape each other in an entangled and unfolding process.

In this approach, the subject of psychology is further decentered. We are not imagining an individual drawing on linguistic concepts circulating within their wider social context, as in social constructionism, but part of an open system of multiple, intersecting (discursive and material) elements that momentarily actualise our object of study, including the person.

An example is clearly going to help here, and we turn to what has become the relatively common place idea that gut bacteria shape our health. When thinking about the relationship between gut bacteria and health, we can conceptualise a unified human body, within which clearly defined gut bacteria reside in multiple numbers (this keeps our sense of a coherent whole intact). Alternatively, we can take a more-than-human approach and imagine an open system, through which multiple elements are in constant flux (e.g., glucose flows across cell membranes, some of which are human and others non-human).

Example of thinking with a more-than-human approach

More-than-human theory is underpinned by a “processual” philosophy that focuses on the continual unfolding of an emerging world, directing attention to those forces that shape the emerging world, rather than its separated-out components. A more-than-human approach radically changes how we might think about the object of our study in health psychology, including where the body begins and ends, and distinctions between human and non-human, including animals or other aspects of the natural world (Burr, 2024; Lupton et al., 2023).

These ideas are not, however, radical in Indigenous thought. We return to our earlier quote from Māori scholar, Pita King, that “atomization is often avoided” (King et al., 2017, p. 731). Indeed, the interconnection and unfolding of human and non-human relations, where the human is not the centre of these relationships, is typically part of Indigenous cosmologies (Hokowhitu, 2020), and may offer important directions for enhancing human relations (Bansal, 2020).

Conclusion

We started this chapter saying that if health psychology is about supporting people towards health and wellbeing, we have to ask, “What kind of person are health psychologists thinking of?” Chapter 1.1 had already started this work with discussion of te ao Māori. In this chapter we built on that discussion by considering four Western approaches to conceptualising of the person. Asking such a fundamental question speaks to the critical health psychology pou of challenging taken-for-granted understandings, and thinking critically, and reflexively, about the conceptual frameworks we use. At the end of this chapter, we hope you now have a better understanding of why we asked that question, and also the potential ways you can answer it.

Key takeaways from this chapter

- The biopsychosocial approach, is an example of how mainstream psychology conceptualises the person as an individual separate to the world, who then interacts with it, and whose health practices can be modelled by identifying atomised factors that predict behaviour across contexts. Although there is sophisticated modelling employed in this approach, the underlying principles tend to be under theorised.

- Phenomenological psychology offers a more theoretically developed approach that also focuses on the individual. It conceptualises the person as an interpretative being, whose interpretations of their health experiences are produced through embodiment, temporality, spatiality, affect, intersubjectivity, and personal histories.

- Social constructionism constructs the person as produced through language, and as multiple, contradictory, fluid, and partial because there is always more than one way to understand the world in any linguistic community. Health psychologists employing this theoretical approach tend to focus on how people make sense of their health, and the implications that meaning-making has for what they can say, think, feel, or do.

- More-than-human theories consider how meaning-making and the material, the human and non-human, dynamically interact in an ongoing process that produces experiences of health.

We started this chapter with a map metaphor for thinking about these different approaches. The usefulness of a map depends on the context in which it is being used and its user’s desired outcomes. Thus, while critical health psychologists tend to prefer approaches that are richly theorised and less individualistic, we recognise that all approaches offer potentially useful maps depending on context. So rather than making a case for one being better than the other, we encourage you to think about the possibilities and limitations in all of them.

Further, although there are significant distinctions between approaches, we also note there are important synergies. Social constructionist and more-than-human approaches stand in contrast to individualised approaches, for example, since they conceptualise people as produced through their social context. Additionally, Kaupapa Māori (discussed in Brittain & Kora Chapter 1.1), social constructionist, and more-than-human approaches share the idea that our understandings of the world are produced relationally, and that power shapes those understandings.

In the next chapter, we build on what we have discussed so far, helping you develop your familiarity, and thus understanding of these ideas. We do so by considering how different approaches shape the psychological knowledge that we produce and use in health psychology, considering, (1) Kaupapa Māori, (2) mainstream psychology, (3) phenomenological psychology, (4) social constructionist and (5) more-than-human approaches.

Knowledge Check

Want to know more?

Watch: “The Century of the Self” (Episode One – Happiness Machines) (Curtis, 2002). This episode explores some of the ways the self has been understood in the 20th century, and how these ideas have been leveraged to shape people’s identity, desires, and behaviour. (You can find it on various platforms including YouTube and the BBC iPlayer).

Listen:

“Where’s does the power lie? A critical look at the biopsychosocial model with Karime Mescouto”, on The Words Matter Podcast with Oliver Thomson (Thomson, 2021).

Read: Chapter 6 “Self, identity, subjectivity” in Gough, B., McFadden, M., & McDonald, M. (2013). Critical social psychology: An introduction (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing.

Also see Morison and Gibson Chapter 2.1 for further discussion of the biomedical and biopsychosocial models.

References

Ahmed, S. (2014). The cultural politics of emotion (2nd ed.). Edinburgh University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt1g09x4q

Aho, K., Dahl, E., Falke, C., & Eriksen, T. E. (2019). Notes from a heart attack: A phenomenology of an altered body. In E. Dahl, C. Falke, & T. E. Eriksen (Eds.). Phenomenology of the broken body (pp. 188–201). Routledge.

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action control (pp. 11–39). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-69746-3_2

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1972). Attitudes and normative beliefs as factors influencing behavioral intentions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 21(1), 1–9.

Almuwaqqat, Z., Wittbrodt, M., Young, A., Lima, B. B., Hammadah, M., Garcia, M., Elon, L., Pearce, B., Hu, Y., Sullivan, S., Mehta, P. K., Driggers, E., Kim, Y. J., Lewis, T. T., Suglia, S. F., Shah, A. J., Bremner, J. D., Quyyumi, A. A., & Vaccarino, V. (2021). Association of early-life trauma and risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in young and middle-aged individuals with a history of myocardial infarction. JAMA Cardiology, 6(3), 336–340. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2020.5749

Alvesson, M., & Sköldberg, K. (2017). Reflexive methodology: New vistas for qualitative research (3rd ed.). Sage Publications Ltd.

American Psychological Association. (2024). APA dictionary of psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org/

Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta‐analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(4), 471–499. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466601164939

Baboulene, K. (2020). Meaning-making of the subjective experience of psychosis, when subject to a dominant psychiatric discourse: A dynamic phenomenological and discursive analysis [PhD Thesis, City, University of London]. https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/26434/

Bansal, P. (2021). Big and small stories from India in the COVID19 plot: Directions for a ‘post coronial’ psychology. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 55(1), 47–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-020-09585-6

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv12101zq

Barlow, M. A., Liu, S. Y., & Wrosch, C. (2015). Chronic illness and loneliness in older adulthood: The role of self-protective control strategies. Health Psychology, 34(8), 870–879. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000182

Billig, M., Condor, S., Edwards, D., Gane, M., Middleton, D., & Radley, A. (1988). Ideological dilemmas: A social psychology of everyday thinking. Sage Publications.

Bolton, D., & Gillett, G. (2019). The biopsychosocial model of health and disease: New philosophical and scientific developments. Palgrave MacMillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11899-0_1

Boroditsky, L. (2017). How language shapes the way we think. TED. https://www.ted.com/dubbing/lera_boroditsky_how_language_shapes_the_way_we_think?audio=en&language=en

Box, G. E. P. (1976). Science and statistics. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 71(356), 791–799. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1976.10480949

Braidotti, R. (2013). The posthuman. Polity Press.

Burr, V. (2015). Social constructionism (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315715421

Burr, V. (2025). Social constructionism (4th ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003335016

Coulthard, G. S. (2014). Red skin, white masks: Rejecting the colonial politics of recognition. University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816679645.001.0001

Crossley, M. (2008). Critical health psychology: Developing and refining the approach. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00041.x

Curtis, A. (Director). (2002). Happiness machines (Episode 1) [TV series episode]. In The century of the self. BBC.

Danziger, K. (1997). Naming the mind: How psychology found its language. Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446221815

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press.

Eberle, T. S. (2022). Phenomenology: Alfred Schutz’s structures of the life-world and their implications. In U. Flick (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research design (Vol. 2, pp. 107–126). Sage Publications.

Elias, N. (2000). The civilizing process: Sociogenetic and psychogenetic investigations (E. F. N. Jephcott, Trans., 2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.847460

Foucault, M. (1976). The birth of the clinic: An archaeology of medical perception (A. M. Sheridan, Trans.). Travistock Publications.

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Vintage Books.

Foucault, M. (2013). Archaeology of knowledge (A. M. Sheridan Smith, Trans.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203604168

Fox, N. J. (2017). Personal health technologies, micropolitics and resistance: A new materialist analysis. Health, 21(2), 136–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459315590248

Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198237907.001.0001

Friedman, M., & Rosenman, R. H. (1974). Type A behavior and your heart. Fawcett Crest.

Garland-Thomson, R. (2011). Misfits: A feminist materialist disability concept. Hypatia, 26(3), 591–609. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2011.01206.x

Gavey, N. (2018). Just sex?: The cultural scaffolding of rape (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429443220

Geertz, C. (1974). “From the native’s point of view”: On the nature of anthropological understanding. Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 28(1), 26–45. https://doi.org/10.2307/3822971

Gergen, K. J. (1985). The social construction is to movement in modern psychology. American Psychologist, 40, 266–275. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.40.3.266

Gergen, K. J. (1991). The saturated self: Dilemmas of identity in contemporary life. Basic Books.

Gergen, K. J. (1996). Social psychology as social construction: The emerging vision. In C. McGarty & A. Haslam (Eds.), The message of social psychology: Perspectives on mind in society (pp. 113–128). Blackwell. http://www.swarthmore.edu/sites/default/files/assets/documents/kenneth-gergen/Social_Psychology_as_Social_Construction_The Emerging_Vision.pdf [PDF]

Ghaemi, S. N. (2009). The rise and fall of the biopsychosocial model. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 195(1), 3–4. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.109.063859

Gibson, B. (2016). Rehabilitation: A post-critical approach. CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/b19085

Gough, B., McFadden, M., & McDonald, M. (2013). Critical social psychology: An introduction (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing.

Greenhalgh, T., & Wessely, S. (2004). ‘Health for me’: A sociocultural analysis of healthism in the middle classes. British Medical Bulletin, 69(1), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldh013

Guenther, L. (2020). Critical phenomenology. In G. Weiss, A. V. Murphy, & G. Salamon (Eds.), 50 concepts for a critical phenomenology (pp. 11–16). Northwestern University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvmx3j22.6

Hagger, M. S., & Hamilton, K. (2024). Longitudinal tests of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. European Review of Social Psychology, 35(1), 198–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2023.2225897

Harper, D., & Cromby, J. (2013). Paranoia: Contested and contextualised. PCCS Books. https://repository.uel.ac.uk/item/85zxz

Harré, R. (1979). Social being: A theory for social psychology. Blackwell.

Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199283262.001.0001

Hokowhitu, B. (2020). The emperor’s ‘new’ materialisms: Indigenous materialisms and disciplinary colonialism. In B. Hokowhitu, A. Moreton-Robinson, L. Tuhiwai-Smith, C. Andersen, & S. Larkin (Eds.), Routledge handbook of critical indigenous studies (pp. 131–146). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429440229

Illouz, E. (2008). Saving the modern soul: Therapy, emotions, and the culture of self-help. University of California Press.

Javed, Z., Haisum Maqsood, M., Yahya, T., Amin, Z., Acquah, I., Valero-Elizondo, J., Andrieni, J., Dubey, P., Jackson, R. K., Daffin, M. A., Cainzos-Achirica, M., Hyder, A. A., & Nasir, K. (2022). Race, racism, and cardiovascular health: Applying a social determinants of health framework to racial/ethnic disparities in cardiovascular disease. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.121.007917

Kahl, K. G., Stapel, B., & Heitland, I. (2023). A lonely heart is a broken heart: It is time for a biopsychosocial cardiovascular disease model. European Heart Journal, 44(28), 2592–2594. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad310

King, P., Hodgetts, D., Rua, M., & Morgan, M. (2017). Disrupting being on an industrial scale: Towards a theorization of Māori ways-of-being. Theory & Psychology, 27(6), 725–740. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354317733552

Korzybski, A. (1933). Science and sanity: An introduction to non-Aristotelian systems and general semantics. Institute of General Semantics.

Kwasnicka, D., Hoor, G. ten, Knittle, K., Potthoff, S., Cross, A., & Olson, J. (2021). Practical health psychology (Vol. 1). European Health Psychology Society. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/M72P5

Langdridge, D. (2007). Phenomenological psychology: Theory, research and method. Pearson Education.

Larkin, M., Eatough, V., & Osborn, M. (2011). Interpretative phenomenological analysis and embodied, active, situated cognition. Theory & Psychology, 21(3), 318–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354310377544

Lather, P. (2007). Getting lost: Feminist efforts toward a double (d) science. State University of New York Press.

Lorde, A. (1984). Sister outsider: Essays and speeches. Crossing Press.

Lupton, D., Wozniak-O’Connor, V., Rose, M. C., & Watson, A. (2023). More-than-human wellbeing: Materialising the relations, affects, and agencies of health, kinship, and care. M/C Journal, 26(4). https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.2976

Marks, D. F. (2020). The COM-B system of behaviour change: Properties, problems and prospects. Qeios, 10, U5MTTB. https://doi.org/10.32388/u5mttb

McLaren, N. (2021). The biopsychosocial model: Reality check. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 55(7), 644–645. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867420981409

McPherson, R., & Tybjaerg-Hansen, A. (2016). Genetics of coronary artery disease. Circulation Research, 118(4), 564–578. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306566

Mescouto, K., Olson, R. E., Hodges, P. W., & Setchell, J. (2022). A critical review of the biopsychosocial model of low back pain care: Time for a new approach? Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(13), 3270–3284. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1851783

Michie, S., Van Stralen, M. M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

Mielewczyk, F., & Willig, C. (2007). Old clothes and an older look: The case for a radical makeover in health behaviour research. Theory & Psychology, 17(6), 811–837. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354307083496

Miller, P., & Rose, N. (1990). Governing economic life. Economy and Society, 19(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085149000000001

Monson, E., & Arsenault, N. (2017). Effects of enactment of legislative (public) smoking bans on voluntary home smoking restrictions: A review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19(2), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntw171

New Zealand Psychological Society. (2024). About psychology. https://www.psychology.org.nz/public/about-psychology

NICE (2007). Behaviour change: General approaches. Public health guideline. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph6.

Ogden, J. (2003). Some problems with social cognition models: A pragmatic and conceptual analysis. Health Psychology, 22(4), 424–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.22.4.424

Ogden, J. (2015). Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour?: One of us will have to go! A commentary on Sniehotta, Presseau and Araújo-Soares. Health Psychology Review, 9(2), 165–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2014.898679

Orgad, S., & Gill, R. (2021). Confidence culture. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478021834

Parker, I. (2015). Towards critical psychotherapy and counselling: What can we learn from critical psychology (and political economy)? In D. Loewenthal (Ed.), Critical psychotherapy, psychoanalysis and counselling: Implications for practice (pp. 41–52). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137460585_3

Petropoulos, G. (2021). Phenomenology and ancient Greek philosophy: An introduction. Journal of the British Society for Phenomenology, 52(2), 95–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071773.2021.1899053

Rey Brandariz, J., Guerra Tort, C., Candal Pedreira, C., García, G., Martín Gisbert, L., Ruano Ravina, A., Varela Lema, L., & Pérez Ríos, M. (2024). Evolution and characteristics of studies estimating attributable mortality to second-hand smoke: A systematic review. ISEE Conference Abstracts, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1289/isee.2024.1883

Rice, C., Riley, S., LaMarre, A., & Bailey, K. A. (2021). What a body can do: Rethinking body functionality through a feminist materialist disability lens. Body Image, 38, 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.03.014

Riley, S., Evans, A., Anderson, E., & Robson, M. (2019a). The gendered nature of self-help. Feminism & Psychology, 29(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353519826162

Riley, S., Evans, A., & Robson, M. (2019b). Postfeminism and health: Critical psychology and media perspectives. Taylor & Francis. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/77181

Riley, S., Robson, M., & Evans, A. (2021). Foucauldian-informed discourse analysis. In M. Bamberg, C. Demuth, & M. Watzlawik (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of identity (pp. 285–303). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108755146.016

Riva, M. A., Riva, E., Spicci, M., Strazzabosco, M., Giovannini, M., & Cesana, G. (2011). “The city of Hepar”: Rituals, gastronomy, and politics at the origins of the modern names for the liver. Journal of Hepatology, 55(5), 1132–1136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2011.05.011

Roberts, A. (2023). The biopsychosocial model: Its use and abuse. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 26(3), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-023-10150-2

Robson, M., Riley, S., & McKeogh, D. (2024). Understanding the disconnect between lifestyle advice and patient engagement: A discourse analysis of how expert knowledge is constructed by patients with CHD. Psychology & Health, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2024.2390031

Robson, M., Riley, S., & McKeogh, D. (2025). Multiple temporalities of lifestyle change. In K. Kenny (Ed.), Temporalities. Palgrave.

Rose, N. (1998). Inventing our selves: Psychology, power, and personhood. Cambridge University Press.

Roseboom, T. J. (2019). Epidemiological evidence for the developmental origins of health and disease: Effects of prenatal undernutrition in humans. Journal of Endocrinology, 242(1), T135–T144. https://doi.org/10.1530/JOE-18-0683

Rosin, M., Mackay, S., Gerritsen, S., Te Morenga, L., Terry, G., & Ni Mhurchu, C. (2024). Barriers and facilitators to implementation of healthy food and drink policies in public sector workplaces: A systematic literature review. Nutrition Reviews, 82(4), 503–535. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuad062

Russell, P. L. (2006). The phenomenology of affect. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 76(1–2), 67–70. https://doi.org/10.1300/J497v76n01_07

Smith, J. A. (2007). Hermeneutics, human sciences and health: Linking theory and practice. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 2(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482620601016120

Sniehotta, F. F., Presseau, J., & Araújo-Soares, V. (2014). Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour. Health Psychology Review, 8(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2013.869710

Stainton-Rogers, W. (2017). Changing behaviour: Can critical psychology influence policy and practice? In Horrocks, C. & Johnson, S. (Eds.), Advances in health psychology: Critical approaches (pp. 44–58). Palgrave McMillan.

Stam, H. J. (2000). Theorizing health and illness: Functionalism, subjectivity and reflexivity. Journal of Health Psychology, 5(3), 273–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910530000500309

Steptoe, A., & La Marca, R. (2022). The biopsychosocial perspective on cardiovascular disease. In S. R. Waldstein, W. J. Kop, E. C. Suarez, W. R. Lovallo, & L. I. Katzel (Eds.), Handbook of cardiovascular behavioral medicine (pp. 81–97). Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-85960-6_4

Su, S., Jimenez, M. P., Roberts, C. T., & Loucks, E. B. (2015). The role of adverse childhood experiences in cardiovascular disease risk: A review with emphasis on plausible mechanisms. Current Cardiology Reports, 17, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-015-0645-1