1.4 Equity and power

Sarah Riley; Siobhán Healy-Cullen; Sonja Ellis; Gareth Terry; and Aorangi Kora

Overview

In this chapter, we focus on issues of equity and power, as they intersect with how we conceptualise health. In so doing, we continue our critical reflection on the concepts we use by asking: How do our concepts of health shape possibilities for in/equitable health outcomes?

To address the above question, we start with the distinction between equity and equality. We then introduce a poststructuralist approach for thinking about relationships between power, meaning making, psychology, and health. From this, we consider “healthism”, a term used to describe an individualist orientation to health that makes it a personal responsibility. As a framework for understanding health, we discuss how healthism contributes to a culture of risk and blame, which can make health inequities appear fair or justified. We finish with ways we might work with, challenge, or destabilise this individualist orientation to health. Within each section, we thread through examples relating to health and weight–since weight is often treated as a proxy for health. In so doing, we cover the following learning objectives:

Learning objectives

- Understand why equity issues are important for psychological work seeking to enhance health.

- Critically reflect on how modern power works through psychology.

- Evaluate healthism as a discourse of health.

Introduction

During New Zealand’s 2020 electoral campaign, electoral candidate Judith Collins described weight as a personal responsibility. When challenged, she argued that healthy eating was not “that hard” and that “we can all take personal responsibility” (1News, 2020). These comments were made in response to population statistics showing that Aotearoa New Zealand had the third highest adult obesity rate in the OECD (34% of the population, OECD, 2023), with Māori and Pacific peoples having higher rates than the national average (Ministry of Health, 2015). These statistics, and the politician’s response to them, can be contextualised within an entrenched “obesity epidemic” discourse circulating globally in health and public spheres. This discourse constructs fatness[1] as a significant population health issue, and the outcome of people making poor choices that can be addressed through lifestyle change (Gailey, 2022; Gard, 2010). Collins was therefore simply reproducing normative discourses. Yet push back quickly followed.

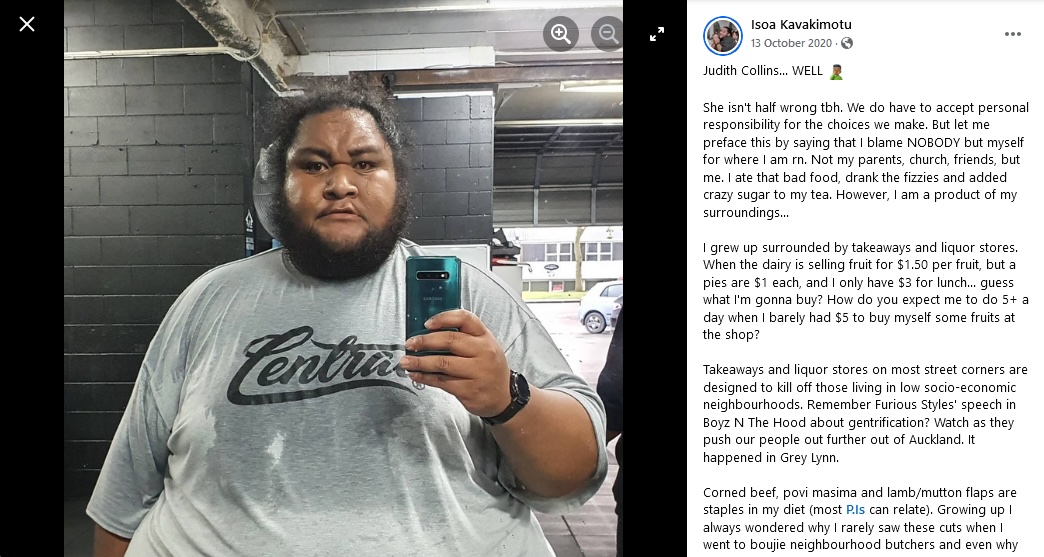

The response that caught the public attention came from a social media post by Isoa Kavakimotu, a Pacific man who grew up in Auckland, whose photograph, along with his post showed him as visibly fat (see Figure 1.4.1).

While acknowledging the personal responsibility discourse, Kavakimotu highlighted social issues, such as the kinds of food, and the price differentials of healthy and unhealthy food that were sold in his neighbourhood, as well as how historic trade systems shaped the diet of Pacific Islanders.[2] See text box below for an abridged version of his post.

Excerpt from Isoa Kavakimotu’s social media post

I grew up surrounded by takeaways and liquor stores. When the dairy is selling fruit for $1.50 per fruit, but pies are $1 each, and I only have $3 for lunch… guess what I’m gonna buy? How do you expect me to do 5+ a day when I barely had $5 to buy myself some fruits at the shop? […] Judith Collins shouldn’t be so dismissive because I’m out here trying to change my own relationship with food and taking responsibility for what got me here. But for her to say “don’t blame the system” is bullshit because this was/is the system in play to enable the fattiest cuts of meat become staples of our diet, and be surrounded by heart attack food

You can read his full post on Facebook, and more posts from Isoa Kavakimotu, see his Facebook page and his Instagram profile.

Kavakimotu’s social media post received significant media coverage and a variety of positive responses (to date, receiving 27,000 thumbs up/heart responses on Facebook). Multiple expert and public voices followed suit, with social justice and equity arguments against the personal responsibility discourse. This Collins-Kavakimotu moment makes visible the multiple, and competing, constructs of health in our time. In this chapter, we consider these ideas in depth, starting with an examination of what we mean by equity.

Equality, equity and social justice

Equality is often treated as a taken-for-granted good thing, defined as treating people the same. In this logic, treating people differently becomes a taken-for-granted bad thing, since it is a practice of inequality. These ideas assume an equal starting point. But since people often do not have the same starting point, treating everyone the same often produces inequitable outcomes, which is why it is useful to make a distinction between equality and equity.

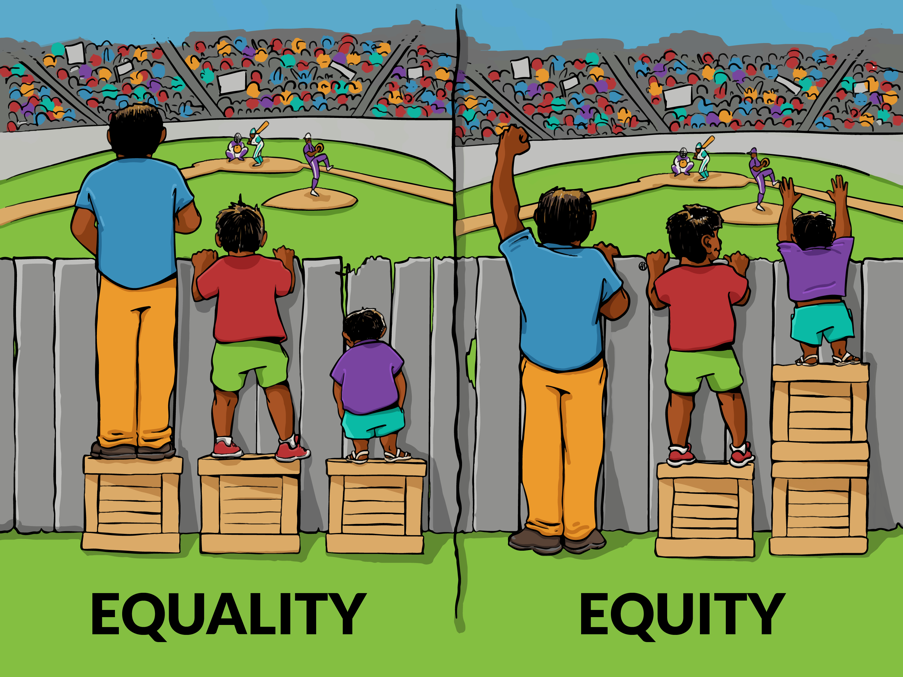

We understand this distinction in relation to physical issues. For example, we do not call it “equality” to expect a person who uses a wheelchair to take the stairs. But it can be harder to see how treating people the same in health contexts can reproduce existing privilege and marginalisation.[3] To address that difficulty, the image in Figure 1.4.2 was designed to visually represent distinctions between equality and equity.

It is therefore often useful to make distinctions between equality, defined as distributing resources equally, and equity, defined as distributing resources in relation to needs and outcomes. As the World Health Organization (2018) states:

Health inequities are differences in health status or in the distribution of health resources between different population groups, arising from the social conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age. Health inequities are unfair and could be reduced by the right mix of government policies.

The COVID–19 vaccination rollout in Aotearoa New Zealand offers us a good example of such distinctions between equality and equity. In 2021, Manatū Hauora Ministry of Health rolled out a phased approached to Covid-19 vaccinations, similar to strategies used internationally. This approach prioritised vaccination for older people according to age brackets because they were at higher risk of severe illness if they contracted COVID-19 (The New Zealand Government, 2021). However, the focus on age, meant that the rollout overlooked intersecting ethnic differences in health needs. For example, in contrast to the majority Pākehā, Māori have higher mortality rates and manage more health conditions – disparities that are rooted in longstanding health inequities. Māori are thus less likely to be in the older age brackets, and when younger, are more at risk for developing severe illness if they contract COVID-19 (Hunt & Bradwell-Pollak, 2022).

The COVID-19 vaccination rollout example demonstrates why it is important to evaluate health policies, and practice, in relation to their risk of producing health inequities. We can expand the remit of critical health work further when connecting it to a social justice agenda, which includes dismantling entrenched social values and meaning making that perpetuate marginalisation (e.g., Bailey et al., 2024; Goodman et al., 2004).

To do this work demands strong critical evaluation skills. Figure 1.4.2 above, for example, is a highly circulated (and thus socially valued) image used to represent equity issues. But critical analysis highlights how it also reproduces the male norm (since the figures are male-presenting), White supremacy (the people who need help are brown), and a deficit orientation to the person who needs “help”, since there is no sense that the shorter person has strengths that could be leveraged (Ann Milne Education, 2021; Mind Reader, 2018).

Accordingly, people have experimented with creating images to represent these distinctions, such as how different size and shaped bodies can ride better on different types of bicycles. Others have focused on showing how fixing the system to enable equal access to opportunities is preferable to adding props to the system (like the boxes to stand on).

Activity: Thinking critically about equality, equity and social justice

Put the search terms “equality and equity meme” in an internet browser image search to explore the variations of these images – consider, which one do you prefer, and why?

Critical reflection is an important part of health psychology because it allows us to identify, challenge, or avoid practices that may seem fair to those managing resources, but which perpetuate marginalisation. Critical reflection also helps identify alternative solutions. It is therefore important that we have the tools for doing critical reflection on power.

The power of discourse

To be able to critically evaluate the way we frame health, we need to think deeply about discourse and power. For this task, the philosophical work of Michel Foucault[4] is invaluable. Although many of his ideas had taken some form in prior feminist writing (Gavey, 2018), and were further developed by subsequent theorising, Foucault’s conceptualising of power as operating through discourse, and being productive, diffuse, and disciplinary, offers an important foundational framework for critical health psychology, as we outline below.

Discourse

In previous chapters, we have used the term “discourse” to describe broad forms of shared cultural sense making that construct an object, or issue, in a relatively coherent way. When doing so, we were drawing on Foucault (e.g., 1977, 1978), who defined discourse as practices that systematically form the object of which we speak. From this perspective, health discourses do not neutrally describe what health is, but actively construct our idea of it:

“Discourses are thus relatively coherent ways of making sense of an issue, they govern how that issue can meaningfully be thought and talked about, which in turn, shapes what people might feel or do. Crucially, discourses are not neutral descriptions of the issue but bring it into being” (Riley, Forthcoming)

Productive power

Foucault distinguished between coercive and productive power. Coercive power is enacted when a person explicitly wields power over the other. Using a contemporary example, coercive power operates when a person cannot access healthcare until they lose weight.

In contrast, productive power operates when some ideas about the world, and the people in it, accrue greater cultural acceptance than others – we can think of this as power that produces particular understandings. Returning to our weight example, productive power occurs when body mass index (BMI) serves as a widely recognised, proxy measure for health (despite evidence challenging this simple notion; e.g., Bacon & Aphramor, 2011; Tomiyama et al., 2013, 2016).

Productive power renders issues (such a health) “knowable”, providing us with ways to make sense of them (e.g., related to weight) and suggesting ways to respond based on such sense making (e.g., weighing people). So, while productive power is not coercive, it is directive in the sense that it shapes how people see and operate in the world.

Applied to how we understand people, productive power is evident in “subject positions”, a term used to describe how discourses produce types of persons or roles that have associated ways of speaking and acting (Davies & Harré, 1990). When people occupy a subject position, they have a particular vantage point from which to understand themselves, or be understood by others. People categorised as “obese”, for example, report finding it hard to have their healthcare professionals consider any symptoms they report as not related to their weight (Pausé, 2014).

Power as diffuse

Foucault also argued that multiple agents circulate similar ideas, which makes power “diffuse”, that is, pervasive and dispersed. Diffuse power can be contrasted with top-down flows of power, such as directives from a singular identifiable source in an autocracy. Associations between health and weight, for example, are familiar to many because they are reproduced in multiple places, and by multiple people, including those in formal institutions related to health, government, or education; as well as in everyday interactions, health and lifestyle publications, social media, and technology (such as when upmarket electronic scales measure adiposity as well as weight).

Disciplinary power

Foucault used the term “disciplinary power” to describe how discourses provide the building blocks for people’s thinking, shaping their internal life (see the Social constructionism section in Riley et al. Chapter 1.2 on people being constituted through language).

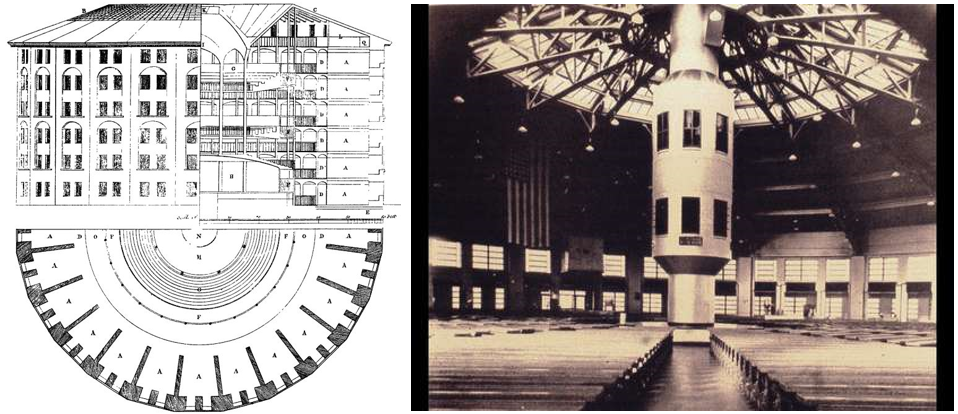

Foucault used the panopticon prison design as a metaphor for disciplinary power (Foucault, 1977). With a central guard tower surrounded by well-lit prison cells (see Figure 1.4.3 below), the panopticon prison was imagined as one where there was always potential for a guard to be looking at a prisoner. Never sure if they were being looked at, the prisoners would thus act as if the guard was looking, in effect becoming their own guard.

Through the process of managing themselves within the norms set by the guard, prisoners in a panopticon would use these norms to think with. These norms were thus shaping their inner most thoughts and feelings, with a prisoner:

“…interiorising to the point that he is his [sic] own overseer, each individual thus exercising this surveillance over, and against himself. A superb formula: power exercised continuously and for what turns out to be a minimal cost (Foucault, 1980, p. 155)

Using the panopticon metaphor, disciplinary power describes how people manage themselves in line with dominant societal constructs, while often feeling like this is driven by their own desires. Norms, surveillance, and examination play an important part of this process:

- norms set expectations

- surveillance measures people against these norms

- examination identifies any need for intervention.

BMI health apps offer an example. Disciplinary power occurs when people download a BMI calculating app, and input their height and weight for the app to calculate their BMI. The app then examines them against programmed norms regarding valued and problematised weight categories (e.g., underweight, healthy weight, overweight, or obese). If the app user’s weight falls outside the “desired” range, the app offers a recommendation, and implied expectation, to change category status (e.g., by providing opportunities to “track your progress”). Such health apps add features to encourage motivation, such as celebration animations when people hit particular targets. Some apps may also put people in groups to hold each other to account. This technological architecture creates affordances related to practices of self–surveillance and examination against the (desired) norm of a “healthy” weight.

Desires for self-transformation

Such practices of self-surveillance, examination, and transformation highlight how people work on themselves to produce themselves into the image of their desires (Foucault, 1988). But people’s desires for who they want to be are shaped by socially-shared meanings, especially those about what it means to be a “good” person or live a “good” life. Discourses and norms thus work “on and through desire” (Zabrodska et al., 2011, p. 710), directing us to understand that certain things, such as a BMI between 18-25, will bring us health and happiness. In our contemporary moment, “good life” discourses are often linked to self-transformation, creating an imperative to be continually working on oneself:

The transformation imperative is enabled by the idea that the body is malleable, and therefore can be transformed, if with the application of effort, money, skill and appropriate use of technologies and expertise (Riley et al., 2023, p. 50).

The transformation imperative has a hopeful, optimistic affective register, it connects with Foucault’s idea of technologies of self, that is, things people do, “so as to transform themselves in order to attain a certain state of happiness, purity, wisdom, perfection or immortality” (Foucault, 1988, p. 18). However, these hopes can produce a form of “cruel optimism” when good life discourses direct people’s desires towards things that may be unattainable or harmful (Berlant, 2011). One example is when restrictive or obsessive dietary and exercise practices are understood as “just healthy eating” (Lewthwaite & LaMarre, 2022, p. 1).

These ideas, about hope and cruel optimism, highlight the role of feelings and emotions in shaping our desires towards, and experiences of, understanding ourselves within a discourse. For example, discourses that associate health, weight, and “goodness” mean that people may feel joy, pride, anxiety, shame, fear, or distress when looking at their BMI calculator apps. These feelings occur, in part, because they understand their BMI as representing something important to them, and about them.

Discourses about feelings and emotions also have disciplinary power because they create “feeling rules”, that is, culturally prescribed norms and expectations about emotional expression (Hochschild, 1979; Wetherell, 2013). Feeling rules are often gendered, and as intersectionality theory argues, gender is always racialised (e.g., Collins & Bilge, 2020; Crenshaw, 1991). For example, women are valued for expressing positivity, which reduces their ability to express anger or other “problematic” feelings (e.g., Calder-Dawe et al., 2021; Orgad & Gill, 2021). For Black women, positive feeling rules can translate into desires to be seen as a “strong Black woman” who can face any challenge thrown at her, and be a source of support for others. The “strong Black woman” is an affirmative subject position, but it also individualises difficulties in Black women’s lives, even when they are related to wider issues such as sexism, racism, cost of living, or existential fears like climate change. Expectations for emotional strength also deny legitimacy to difficult feelings (e.g., anger or vulnerability) and may reduce help seeking (Edeh et al., 2022; Graham & Clarke, 2021; Woods-Giscombé, 2010).

Key takeaways

So far, we have shown how Foucauldian theorising offers a conceptual framework for thinking about power as:

- productive, through discourses that construct how an object, issue, or person can be understood

- diffuse, when discourses circulate across a range of actors and media, and

- disciplinary, because discourses shape people’s thoughts, and thus feelings and desires.

Possibilities for resistance

Agency and resistance can be enacted when people actively shift from one discourse to another. For example, rejecting a weight focused discourse for a weight inclusive one (Calogero, et al., 2019). (For further discussion on how people shift across discourses, see Chapter 1.2 section on Social constructionist models of the person).

But, often it is hard to resist entrenched discourses, and the norms they produce, because to understand oneself within a valued norm is to be able to recognise oneself as “a viable being” (Davies, 2013, p. 24). Think back, for example, to the potential for a person to feel pride when looking at the outcome of their BMI calculator app. It would be hard for them to say that this number does not matter, and if it really did not matter to them, they would have lost the possibility of understanding themselves in a culturally valued way.

Governmentality

In a variety of ways, organisations render people knowable, such as when they categorise people as requiring social support, eligible for healthcare, and so forth. People can draw on these organisational ways of knowing to understand themselves, shaping their desires towards wanting to be known within valued categories. This process of government-produced disciplinary power is known as “governmentality”.

Governmentality can occur as an outcome of administration. For example, census data designed for government planning creates—as a byproduct —different kinds of more, and less, valued categories of people (Miller & Rose, 1997). But, disciplinary power can also be deliberately leveraged to shape people’s thinking and thus behaviour, so that to the people concerned, it feels like they are enacting their own free will:

What makes power hold good, what makes it accepted, is simply the fact it doesn’t only weigh on us as a force that says no, but that it traverses and produces things, it induces pleasure, forms knowledge, produces discourse. It needs to be considered as a productive network which runs through the whole social body, much more than as a negative instance whose function is repression (Foucault, 1980, p. 119).

In the extract above, Foucault contrasts coercive power (“a force that says no … whose function is repression”) to diffuse, productive power that connects to identity and desire (“it traverses and produces pleasure, forms knowledge”). For Foucault, modern power works by inviting people to understand themselves in particular ways, from which they will govern themselves. Governmentality thus refers to how organisations manage people through their psychology.

Government funded BMI calculator apps are an example of governmentality. These apps enact productive power (since they (re)produce the idea that BMI is a proxy for health), and they act as a form of governmentality, since they are made available to people to choose to download and use. Users thus participate in self-surveillance and understand it as empowerment.

We are not criticising people who find such tools empowering. The implication of Foucauldian approaches to power, is not so much that we should identify good or bad discourses, but to examine what capacities for action are enabled or restricted when discourses operate within particular contexts. Returning to our map analogy of Chapter 1.3, poststructuralist theories of power help sensitise us to the maps/discourses we are using to make sense of ourselves. They also lay the foundational work for thinking about the most entrenched map we have for thinking about health in our current moment, the map that was invoked by Judith Collins when she said weight is a personal responsibility, and the topic of our next section.

Healthism

The term ‘healthism’ is attributed to Robert Crawford (1980), a political scientist who outlined a range of interacting factors that produced our contemporary idea of health as personal responsibility and a product of lifestyle choice. Within healthism, health is constructed as a risk, which can be mitigated when people understand that their health is their responsibility and subsequently engage in on-going health-maintaining practices.

Developments in the 1970s in the USA were pivotal in producing the antecedents for healthism. Crawford (1980, 2006) highlighted how this era was characterised, in part, by an anti-establishment attitude, including feminist concerns of how patriarchal medicine ignored women’s lived experience of their bodies. Antiestablishmentarianism was often linked to a highly individualist approach, as seen in the countercultural movements of the time, which sought self-actualisation through radical individualism (Curtis, 2011), and the rise of therapeutic cultures that directed attention to individual psychology (Illouz, 2007). The wellness industry capitalised on these cultural shifts, all of which intersected with the extension of medical issues into everyday life (medicalisation) and secularity, with its associated focus on the here and now (see Turrini, 2015, for more details).

The context outlined above was also shaped by neoliberal economics. Neoliberal economic policies focus on deregulating industry and allowing markets to determine flows of capital, with view to generating a self-adjusting economy and monetary growth. These policies radically shaped 1980s government policies across the globe, including Thatcher’s Britain, Reagan’s USA, Pinochet’s Chilean dictatorship, and the “Rogernomics” of Aotearoa New Zealand. Now, neoliberal policies are pervasive and often taken for granted (Harvey, 2005).

Want to know more about neoliberalism in Aotearoa New Zealand?

Watch: Barry, A. (Director) (2015, April 15). Someone Else’s Country documentary [Video recording].

Listen: Juggernaut: The Story of the Fourth Labour Government, episode 2 “The nation is at risk“.

Embodied neoliberalism. Professor Antonia Lyons recounts some of the key points from the keynote address she delivered at the last ISCHP conference. Informed by her research programme on young adults’ drinking cultures, she reflects on a broad range of issues including gender, social media identity curation, marginalised groups, and neoliberalism.

Read: Groot, S., van Ommen, C., Masters-Awatere, B., & Tassell-Matamua, N. (Eds.) (2017). Precarity: Uncertain, insecure and unequal lives in Aotearoa New Zealand. Massey University Press.

Important for our discussion on psychology, is that neoliberal economies need a particular kind of person, someone who:

- understands themselves to be responsible for their own destiny, who is not reliant on state welfare/services, nor determined by social structures, such as class (Giddens, 1991)

- is risk-managing and self-monitoring and thus able to recognise fluctuations in the market and flexibly adjust accordingly (e.g., by re-skilling for an emerging market or being willing to move to areas of higher employment) (Beck, 1992; Kelly, 2006)

- who understands themselves as a project, and consumption as a route through which they can create themselves (thus meeting the needs of a consumer economy) (Giddens, 1991; Rose, 1998).

Neoliberal citizens are valued for their ability to live productive lives, when productive lives are linked to consumption, economic participation, and not being a cost on the state. Failure to do so represents individual failure.

Neoliberalism and health

When neoliberal logic is applied to health, as in healthism, people are interpellated (i.e., called on) to understand their health:

- as a personal responsibility

- as produced through their lifestyle and consumption practices

- as a risk to be managed through continuous self-monitoring

- as part of their project of self and a measure of whether they are a good person

- as part of their responsibility, as citizens, to live a productive life and avoid being a cost-risk to the state through ill health.

The power of healthism

Healthism has an optimistic tone. It constructs health as an achievable, stable state (if one works hard enough and consumes appropriately). By being linked to morality and citizenship, healthism offers the opportunity to understand oneself as a good person living a good life, and to be understood by others as so doing:

…in a health-valuing culture, people come to define themselves in part by how well they succeed or fail in adopting healthy practices (Crawford, 2006, p. 403).

But, seen through the lens of governmentality, healthism can be read as an enactment of power more closely linked to cruel optimism, as we discuss below.

Health becomes hard work, risky, and expensive

Within healthism, health is not a given, but a risk to be managed. This is for everyone, regardless of health status, since even when one feels healthy, there may be hidden problems potentially developing! The optimistic tone of healthism thus shifts towards anxiety. Healthism is also connected to a transformation imperative, and associated consumer practices to effect that transformation (e.g., expensive blenders and fruit to go in them) that require resources in time, money, and skills, and moving health out of reach for people without these resources.

Health is also hard work because it requires significant knowledge, “responsibilising” people to gain and keep up with medical knowledge related to health. This can feel hard in a complex health environment, with many experts and contradictory advice shared across traditional and social media, and a proliferation of practices people feel expected to do. This complexity means that alongside the importance of getting it right, there is difficulty in getting it right.

Ill health is stigmatised within a logic of blame

If a person does not look “healthy” (when health is read as a slim athletic body), or if a person is ill, then the implication within healthism is that they made poor choices, creating a logic of blame. For example, when psychologist Carla Willig had a potential melanoma, her friends asked questions that implied her responsibility (“Did you use a sunbed?”) (Willig, 2011).

Within healthism, ill health becomes read as a moral failure. This stigmatises ill health, reproduces the mythical norm (discussed in Chapter 1.2), and casts any deviation from the “ideal”—including disability—as “a diminished state of being human” (Bailey et al., 2024, p. 348, citing Campbell, 2008, p. 44). This sense making therefore also produces an “eradication” discourse, where non-normative bodies are positioned as needing fixing, changing, or eradicating (Gillon & Pausé, 2021). It is through noting such eradication discourses that critical scholars consider healthism to be part of a continuation of the eugenics movement (Bailey et al., 2024; Klein, 2023).

The logic of blame can cause distress when people become ill (e.g., Robson et al., 2023), when those they care for become ill, or when they are too ill to care for their dependents (e.g., Parton et al., 2019). Furthermore, it can limit people’s engagement with health care when it connects to shame or stigma (Kashkari & LaMarre, 2024; Singh et al., 2012).

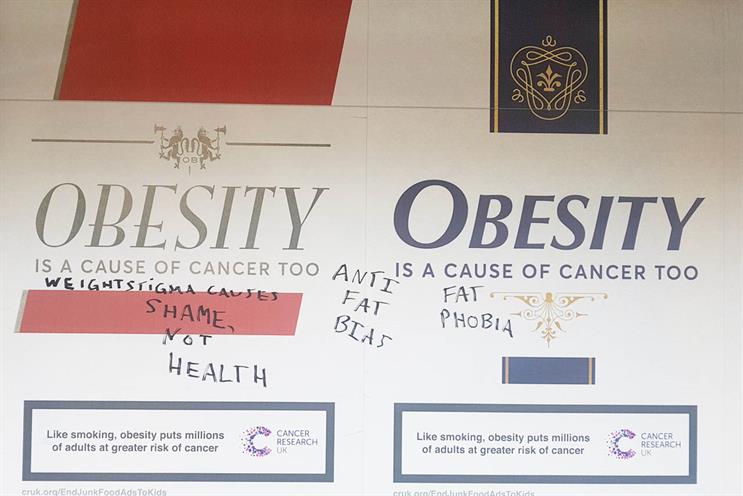

Relatedly, healthism underpins public health campaigns that place responsibility on individuals for their health behaviours, which can lead to stigmatisation, guilt, and shame (Lupton, 2014, 2016). See Figure 1.4.4 below. Such campaigns ignore the well-established links between health/wellbeing and broader economic, social, and cultural factors that shape health, masking the structural inequities that influence health behaviours, especially among marginalised populations (Sumibcay, 2024).

Subjectivity

When health becomes an identity, people’s sense of self is shaped by how much they understand themselves as adopting healthy practices, or being read by others as adopting them. An advantage of this, is that people might participate in health practices more, such as doing an extra walk, motivated by the sense of “doing health” or enjoying the subject position of a “healthy person”.

But when health is defined in terms of lifestyle choices that can be visibly read on the body, people’s sense of self can become wrapped up in appearance and self-scrutiny (Graham et al., 2017; Kristensen et al., 2016; Riley et al., 2019; Tischner & Malson, 2012). This opens possibilities for negative psychological outcomes or health practices, such as appearance-related anxiety, dietary restriction, and excessive exercising.

Practices of self-scrutiny can also be applied to others, producing a surveillance culture in which people scrutinise themselves and others, and watch themselves being scrutinised by other people (Riley et al., 2016; Robson et al., 2023). This, in turn, further heightens an internalised awareness in people of their own performance of a healthy body (Rysst, 2010).

Such dynamic, critical looking can also harm people’s relationships. Robson et al. (2023), for example, showed how couples applied health surveillance to their partners as well as themselves, as a form of “relational healthism”. Their work showed that healthism’s emphasis on surveillance, control, and discipline contravened relationship norms of support, acceptance, and respect for the other’s autonomy, creating contradictory demands for people when enacting loving relationships.

These subjective and relational effects are intensified when healthism intersects with gender, in particular, with postfeminism, a term that describes a dominant framing of femininity that:

renders the intense surveillance of women’s bodies normal or even desirable, that calls forth endless work on the self and that centres notions of empowerment and choice while enrolling women in ever more intense regimes of ‘the perfect’ (Gill, 2017, p. 609).

Postfeminism intersects with healthism, blurring the boundaries between health and appearance, and interpellating a range of feminine-identified people to understand that working on their bodies to meet normative constructs of feminine health/appearance is empowering. The outcome is a “postfeminist healthism”, a term that describes how work on the body and mind to meet cultural norms of feminine health and beauty, is understood as the route to living a good life, and being recognised as doing so by others (Riley et al., 2019, 2023). For example, aesthetic procedures are increasingly framed as not just a personal choice, but an act of self-care and an expression of self-worth, “because you’re worth it” (Pussetti, 2021; Riley et al., 2019, 2023). Relatedly, appearance concerns and diet cultures, which had become subject to public concerns regarding body image, got an affirmative rebrand through their connection to health (Cairns & Johnston, 2015), as seen the proliferation of images of women joyfully eating salad (see Figure 1.4.5 below).

Postfeminist healthism also shapes practices of health associated with masculinity, especially when binary concepts of gender intersect with a “masculinity in crisis” discourse that serves to distance men from feminised practices. This can include encouraging men to avoid salads, to participate in exercise regimes designed to enhance muscularity rather than (slender) flexibility, and even the public shaming of men with eating disorders more commonly associated with women (Riley et al., 2023).

Limited solutions

In the context of postfeminist healthism, solutions become individualised and individuals responsibilised. For example, in an article about healthy lifestyle in menopause (Mishra & Mishra, 2011), the nine-sentence abstract contained eight instances of modal verbs, such as “should”, “should not”, “must”, as well as the term “imperative”.

Individualised solutions, such as listing exercises people should do, rarely considers the social contexts within which people try to enact health. This is despite substantial evidence that the social determinants of health (see Table 1.4.1 below) have greater impact on health than individual lifestyle change (Barnett & Bagshaw, 2020; Hodgetts & Stolte, 2017; Wilkinson & Marmot, 2003).

The social context includes whether it is safe, or possible, to exercise; as well as social norms, such as how women often bear disproportionate responsibility for providing and preparing food for the family, further reducing their time for other activities (Fielding-Singh & Dmowska, 2022; Tischner, 2012). Research on the social context of people’s health practices also shows the many cost-benefit assessments that low-income families must make, which lead to them buying cheaper foods that are higher in fat, sugar, and salt. Such assessments are absent in the “individual choice” argument (Arlinghaus & Laska, 2021; Daniel, 2020; Ward et al., 2013). Relatedly, Warin et al.’s, (2015) ethnographic study of Australians in a low socioeconomic neighbourhood targeted with a public health intervention on healthy eating, showed how a discourse of future risk of ill health mitigated by current lifestyle change required an orientation to the future that was not possible when people were living day to day.

Individual solutions also cause other issues when they intersect with culture. Greenhalgh and Wessely (2004), for example, describe how healthism has produced a middle class subculture[5] of health recognisable in doctors’ surgeries in the UK. This is linked to inappropriate requests or expectations that undermine the doctor patient relationship, including rejection of medical expertise for alternative medicine solutions and requests for referrals or treatments in the privatised sector that the doctor does not recommend.

Individual solutions cause different difficulties for more collectivist communities, since individual solutions go against cultural norms and practices, as shown in Kashkari and LaMarre’s (2024) analysis of South Asian Muslim individuals’ experiences of type 2 diabetes healthcare in Aotearoa New Zealand. Relatedly, notions of “personal responsibility” and “individual success” that underpin a healthism approach are antithetical to Māori perspectives on health. Further, when health is defined in narrow terms, disabled, fat, and racialised bodies, especially, are positioned as outside of health and undesirable, making places of self-improvement feel unwelcoming:

the fitness and leisure sector tends to capacitate bodies already imagined as able or capable and to debilitate or ignore those deemed unwanted, disposable, and non-vital (Bailey et al., 2023, 2024, pp. 351–352; also see Rinaldi et al., 2021).

Affect

Within healthism, health is hard work, exclusionary, complicated, and difficult, yet also a measure of a person and a valued identity. As an ongoing project of the self, even those who have “achieved” health can never be confident of sustaining this position. Such a context produces the conditions of possibility for a range of feelings, including, joy, pride, shame, anxiety, distress, dissatisfaction, and fear.

These feelings can tie people closer to the norms of healthism, in line with our discussion of disciplinary power above. Conversely, in the context of so many demands and practices, people, feeling exhausted or anxious can turn away from health (Crawford, 2006). These various feelings can also shape relations with others. For example, fat and skinny women report people commenting on their body in ways that make them feel uncomfortable or distressed, and the source of other people’s envy or hatred[6] (Riley et al., 2023).

Commercial solutions for health

An individualised lifestyle orientation to health that aligns with consumerism, will logically position consumer culture, and the associated commercial sector, as offering solutions to health. This logic puts commercial vested interests at the centre of health practices and interventions (Dutta, 2016), as when governments partner with companies like Weight Watchers (Cobiac et al., 2010; Mahase, 2020), or Coca-Cola sponsors anti-obesity initiatives in schools (Powell & Gard, 2015). The concern is that such public-private partnerships may:

- prioritise profit over public or individual health goals

- direct attention onto individual solutions for social problems

- promote products or services that are not necessarily beneficial to health, or are unhealthy

- connect health to products that may be unaffordable or unrelated to health

- shape discourses of health, and a healthy life, towards vested commercial interests

- elicit continuous desire for product rather than sating it with lasting solutions (thus feeding consumers back into cycles of consumption that meet the needs of capitalist profit generating systems).

Surveillance in health insurance policies

The integration of tracking apps with health insurance policies exemplifies Foucauldian ideas of power as operating through surveillance, norms, and examination. In Aotearoa New Zealand the public health system (Te Whatu Ora – Health New Zealand) provides only some services at no cost. Others are low cost through subsidies, and others still are paid fully by patients. In this context, many people have additional private health insurance to cover these gaps (Blumberg, 2006).

Some insurers collect data from wearable devices and apps on physical activity, sleep, and self-care (e.g., meditation), linking specific behaviours to rewards within insurance plans, and offering, for example:

… a science-backed health and wellbeing programme that gives you more out of life so you can start thriving. It shows you how healthy you are now, provides you with tools you need and offers rewards and discounts to keep you motivated along your journey (AIA Insurance, www.aia.co.nz, retrieved December 11, 2024).

This language frames health as an aspirational, quantifiable state of optimal functioning (“thriving”). By offering rewards and discounts to “keep you motivated”, the programme reinforces the idea that health is a personal (endless) journey tied to consumer choices. The programme also normalises specific health metrics (e.g., gym visits) as markers of a “healthy” life, measuring insurees against these norms, with incentives like discounts and rewards serving as a mechanism of power to encourage compliance.

Amongst joyful images of youthful, slim healthiness, the promise of “thriving” becomes a moral imperative. This can result in a range of affective responses (shame, guilt, anxiety) since the language used by the health provider frames those who cannot/decide not to participate as neglectful of their own wellbeing, or as choosing not to “thrive”. Siobhán experienced this tension firsthand when choosing health insurance. The external rewards were appealing, as was motivation to participate in healthy activities, even while she was concerned about how insurers were embedding surveillance into health policies, and the way these policies widen inequities by excluding those who cannot afford or access such technologies (Martani et al., 2019; Presset & Ohl, 2023).

Different kinds of solutions

Above, we have outlined problems with individualised health solutions. In this section we consider some directions for thinking about health, equity, and power that more strongly align with the pou of critical health psychology. These are:

- critically evaluating discursive constructions

- producing alternative discourses

- foregrounding the social determinants of health

- employing holistic constructs of health.

Critically evaluating discursive constructions

Above we have highlighted the problems of individualism in health, especially the personal responsibility discourse. And so, we start this section by suggesting caution about its use. As illustrated by the supportive response to Kavakimotu’s post, people are pushing back against the personal responsibility discourse that dominates discussions about health. Relatedly, popular culture also offers a site for critical, and humorous, responses to dominant constructions, such as the “women laughing alone with salad” memes that parody postfeminist healthism (see Figure 1.4.6 below).

We note that Foucauldian theories of power emphasise how all discourses open some possibilities while closing others. The complexity of the discursive space means the consequences of discourses in shaping capacities are unpredictable (Hook, 2001). Aligning with our critical health psychology pou of knowledge in social context, the implication of what we have discussed is that we need to identify and critically evaluate the discourses we use when working in health psychology. Further—in an ongoing way—we need to assess them for their potential to enable health or perpetuate marginalisation, stigma, pathologisation, and othering. See text box on “nudge” below for such a discussion.

What is nudge? By Paulina Bondaronek

Nudging involves interventions that change people’s behaviour in predictable ways by modifying how choices are presented (choice architecture) to encourage healthier or more favourable decisions while preserving freedom of choice. For example, placing fruit at eye level in a supermarket is a nudge, but banning junk food in hospitals is not. As Thaler and Sunstein (2009), who coined the term, state: “To count as a mere nudge, the intervention must be easy and cheap to avoid” (p. 6).

Nudge theory has attracted significant interest among policymakers and is grounded in dual processing theories. These theories, popularised by Daniel Kahneman’s (2011) book Thinking, Fast and Slow, distinguish between automatic, fast processing (System 1 – based on feelings, habits, instinctive responses) and controlled, slow processing (System 2- reflective, logical, problem-solving and planning). Nudges target System 1 by simplifying decisions, making healthier choices more intuitive and less effortful.

Practical applications of nudge theory in public health

Examples of nudge interventions include using traffic light labels to highlight healthy choices. Signs encouraging stair use, visible bike racks, offering smaller glass sizes for wine, prominently placing non-alcoholic drinks, implementing graphic warning labels on cigarette packaging to deter smoking, and making organ donation opt-out are other strategies (Arno & Thomas, 2016; Landais et al., 2020). With attention to context, these interventions can have an impact on physical activity and diet.

Criticisms and ethical concerns

Nudging can undermine autonomy by subtly influencing choices without individuals’ awareness, raising concerns about manipulation of the decision-maker. Additionally, covert nudges can lead to decisions made without informed consent, potentially causing regret and distrust. Furthermore, the predictability of nudges is not always guaranteed; they may backfire, causing reactance or other unintended negative outcomes, which complicates their ethical application. For example, if a cafeteria prominently labels certain items as “healthy” while implicitly labelling others as “unhealthy”, this can lead to reactance, where people deliberately choose the less healthy options as a form of resistance against the perceived control (Kuyer & Gordijn, 2023; Sunstein, 2015).

Consideration of ethical concerns also needs to be contextualised within our wider capitalist context, where commercial interests already structure choice architecture. We are constantly “nudged” but who is nudging most effectively? Nudge interventions therefore do not occur in a truly “neutral” environment. In this context, do we need stricter regulation of commercial practices that exploit our automatic responses (System 1) before we nudge?

Equity and power in the context of nudging

As indicated above, promoting healthy behaviours through nudging is challenging when commercial interests shape choice architecture, exploiting System 1 to create desires for unhealthy options in the first place. This can lead to interventions that fail to address underlying inequities, such as the broader socioeconomic context that relates to access to resources and health literacy. For example, unhealthy food outlets are more common in poorer neighbourhoods (“food deserts”). As discussed earlier in the chapter, not only does this undermine efforts to increase healthy eating through nudging, but it can facilitate a logic of blame where poor people are framed as making poor choices.

A critical health psychology approach might therefore accept that nudging can be a useful tool for health psychology, but only in the context of careful reflection, which includes (1) who is doing the nudging, (2) the ethical values underpinning the intervention (e.g., if eliciting shame is considered appropriate), and (3) the power relations creating the context for the need to nudge in the first place, and if these should be addressed instead or as well.

Discussion point

Thinking of a health issue that you would like to change, reflect on:

- the choice architecture it is embedded in

- the System 1 and 2 elements that are involved in this architecture.

With this knowledge, what sort of intervention would you design?

Producing alternative discursive constructions

Paying attention to discourse involves not just challenging taken-for-granted discourses about body/minds, but exploring alternatives. Fat studies scholars have, for example, rejected seeking to define what health “is” (which tends to stigmatise fat people), and instead, ask affirmative questions around “How can we promote health for fat people”? (Burgard, 2009).

Another example of reframing comes from Warin et al.’s, (2015) ethnographic study of Australians in a low socioeconomic neighbourhood targeted by a public health intervention on healthy eating (discussed above). The researchers challenged the dominant narrative that such people were failing to focus on the risk of future ill health. Instead they highlighted poor people’s innovative strategies for survival in the present, and the responsibility of public health interventions to recognise the socioeconomic and material contexts within which people make decisions, and tailor interventions accordingly.

People participating in online health cultures can also resist healthism through role modelling of alternative, relational care practices that recognise a collective vulnerability and centre responsibility for care of others (Toffoletti, et al., 2025). Participatory research, and collaboration, is another way to shift the discourse, since it enables the people targeted by health policies and practices to contribute to the services designed to support them (NICE, 2007; Szaflarski & Vaughn, 2015; Taylor & Hanefeld, 2021).

Decolonisation also involves opposing taken-for-granted discourses by illuminating, and challenging, the ongoing implications of colonialism on health and wellbeing (Hawaiiki et al., 2024). Decolonising psychology involves kōrero (conversations), listening, and unlearning ingrained beliefs and practices. Listening requires non-Indigenous people to hear perspectives that may be new or different, and which may be difficult to hear at first, especially if they challenge taken-for-granted knowledge (see Introduction Part One for distinctions between lovely and difficult knowledge). By “unlearning”, we mean the active identification and resistance of internalised colonial logics that position Indigenous knowledge and peoples as inferior or deficit, and simultaneous engagement with Indigenous thinking that can widen the discursive framing of health issues. For example, in their article exploring Kaupapa Māori perspectives of fatness and health, Gillon and Pausé (2022) discussed how words in te reo Māori (Māori language) that are associated with fatness widen discursive possibilities for value and pleasure. For example:

“mōmona“, which is often used for the word fat, however it also means in good condition, rich, fertile, nourished. Also, to ‘”whakamōmona” is to make something fat, to enrich it, to nourish it (Gillon & Pausé, 2022, p. 13).

Re*vision projects that shift the discourse

Re*vision, Centre for Art and Social Justice (https://revisioncentre.ca), has undertaken a range of projects seeking to widen possibilities for thinking about fat, Indigenous, and disabled ‘crip’ bodies that challenge harmful weight stigma discourses. Examples of projects include:

- “Through thick and thin: investigating body image and body management amongst queer women in Southern Ontario”. The project included a video story “My Mi’kmaw body” by a participant whose statement “I have a proud survivor’s body”, explains how her weight represents the strength of the Indigenous Mi’kmaw people to survive extreme (social and environmental) conditions because they could store fat well.

- “ReVisioning Fitness” also made short videos centring the lived experiences of trans, non-binary, queer, Black, radicalised, disabled, and fat/thick/thick/curvy people’s fitness-related experiences and inventiveness. Their aim was to reimagine fitness spaces that could centre and celebrate difference and unsettle “white supremacy in fitness” (p. 353). As one participant explained:

My intention was as a Black and plus sized woman, to let people know, who are like me, that they are not alone. And for [white, thin, able-bodied] people who dominate the gym space to realize what they are doing. Sometimes they might not realize what that does to someone. And my video doesn’t just target Black plus sized women, but everyone who feels uncomfortable in the gym (Bailey et al., 2024, p. 358).

- Worlding Difference is an open access online platform filled with counter hegemonic knowledge about bodymind difference, built by, for, and with difference. It invites visitors to imagine new accessible worlds and ways of being together, offering an entry into crip culture, desiring neurodiversity, aging vitalities, and counter-culture making as resistance. It contains contributions from 200 artists, academics, and community members.

Foregrounding the social determinants of health

An important way people can challenge taken-for-granted discourses that individualise health is to focus their work and interventions on the social determinants of health (see textbox below).

List of the social determinants of health as outlined by WHO (2024)

Income and social protection

Education

Employment and job security

Safe and fair working conditions

Food security

Housing, basic amenities, and a safe living environment

Support for early childhood development

Social inclusion, equity, and non-discrimination

Peaceful and cooperative societies/nations

Access to affordable health services of decent quality.

A social determinants of health approach often means promoting health widening capacities and capabilities of people by focusing on the social and environmental levels. One example is ensuring safe environments for physical activity by addressing adequate lighting and footpath infrastructure (Stephens and Breheny, 2018). Acknowledging colonisation as a social determinant of Indigenous peoples’ health, including Māori, also recognises the long-lasting impacts of historical events and offers broader understandings of health status.

Racism’s impact on pregnancy outcomes

This excerpt from When the Bough Breaks explores the impact of racism on pregnancy outcomes.

It illustrates how a lifetime of exposures to racism can literally get inside the body and affect the health of new-borns. Those from lower socioeconomic groups are also at greater risk of poor health due to factors such as poor-quality housing, hazardous work conditions, and other risk imposing environments that no amount of investment in self-improvement technologies will mitigate.

The social determinants of health approach highlights how people on low incomes may be more likely to eat highly processed, (often) cheap food as a matter of necessity rather than choice, when healthy diets including fresh fruit, vegetables, wholegrains, and lean meat are unaffordable and unavailable (Bowen, et al., 2019). These obesogenic environment arguments have gained traction in recent years and offer important directions for social and policy interventions (O’Dea et al., 2007; Sushil et al., 2017).

However, care should be taken about the idea that people will make “good” consumer choices when facilitated to do so (i.e., when healthy food is affordable and available), since this argument ignores psycho-social and affective aspects of eating. For example, people often enjoy eating sugary/fatty foods. This pleasure can relate to the sensation of taste, but in the context of poverty, it may be one of few pleasures available (Ngawhika, 2020; Warin et al., 2015). Sweet/fatty foods are also often part of valued cultural practices and markers of identity, developed when calories were hard to access, but made risky when traditional ways of eating intersect with industrialised food supply systems (Thow et al., 2010).

Within the social determinants of health, therefore, we also need to consider the commercial determinants of health. The “commercial determinants of health” refers to the influence exerted by commercial actors, such as industries involved in the production and marketing of goods and services related to health, as well as those providing solutions to health problems.

Examples include the alcohol and food industries, whose marketing practices, product formulations, and lobbying efforts can profoundly shape public health outcomes. For instance, the promotion of unhealthy food and beverages contributes to rising rates of obesity and diet-related diseases (Kickbusch et al., 2016; Stuckler et al., 2012; also see the “Commercial solutions for health” section above and the Podcast with Antonia Lyons in the “Want to know more about neoliberalism in Aotearoa New Zealand?” section above.

The digital determinants of health

In this mix, we also highlight the importance of challenging the individual choice discourses embedded in the roll out of digital health technologies. As digital health technologies —such as health tracking apps and wearable devices—become increasingly integrated, already underserved populations may be further marginalised through inequitable access to these technologies. For example, those with low incomes may not be able to afford the technology, or the data required to use them, reducing their ability to participate in “the digital health ecosystem” (Lupton, 2017, p. 2; Lupton, 2022).

Jahnel et al. (2022) describe this phenomenon as the “digital rainbow”, whereby interlocking factors such as socioeconomic status, housing, healthcare services, and so forth, come to bear on people’s use of digital health resources, shaping health outcomes. They offer an example of the German COVID-19 warning app (Corona-Warn-App, CWA). Usage analyses of the app highlighted significant social stratification, partly because the languages of major immigrant communities, who were overrepresented in high-exposure public–facing jobs, were not available on the app, exemplifying how digital determinants can deepen health inequities.

Others highlight how the dominance of Western sensibilities in digital health technology means that consideration of Indigenous peoples’ cultural needs is rarely incorporated into the designs. For Indigenous people, this increases the risk of digital exclusion, inadequate care, and loss of sovereignty over their health data (Choukou et al., 2021; Cordes et al., 2024; Naderbagi et al., 2023).

Holistic constructs of health

Holistic constructs of health also offer alternatives to the individualistic focus of healthism. Māori models, such as the Meihana Model (Pitama et al., 2007, 2017), for example, highlight how health is produced through multiple, interconnected elements. These include the four described in Te Whare Tapa Whā model (Durie, 1985), namely aha wairua (spiritual wellbeing), taha tinana (physical wellbeing), taha hinengaro (psychological/mental wellbeing), and taha whānau (family wellbeing), but also other elements, such as those that account for the historical and social context of Aotearoa New Zealand, including the ongoing impact of colonisation, migration, marginalisation, and racism for whānau (see Brittain & Kora Chapter 1.1 for further discussion of these models[7]). Holistic models emphasise how health is contingent on all these elements and the dynamic interactions between them; and that what impacts one element, impacts all the others. For example, strong connections to whānau, whenua, and whakapapa can be spiritually, mentally, and emotionally healing while dis-connection from those same dimensions can have the opposite effect. Relatedly, Gillon and Pausé explain:

Evident in te reo Māori, the Māori language, is the complexity of health. “Hauora” is a Māori word often used for health and wellness. Hauora also means to be fit, well, healthy, vigorous, in good spirits. The word “hau” is understood as vitality, vital essence, and “ora” is understood as well, safe, cured, to be alive, to recover, to be healthy; ora is vitality and ora is life … This highlights the ways in which health for Māori centers not only around cultural and holistic interpretations, but also, anti-oppressive notions of wellness, for example, ensuring Māori live sovereign lives, exercising agency and self-determination (2021, p. 11).

In this quote, we see not just the interconnectedness of multiple factors shaping health, but an extension of what these factors might be, which goes far beyond individual lifestyle choices, and towards explicit considerations of power. An important contribution to these debates is offered by Warbrick et al. (2016, p.394), whose article showed the harm that an individual, weight-centred orientation to health can do to Māori, and which offered, instead “a new epistemology for Māori health” that included how Māori would recognise the significance of the land supporting the house in the Te Whare Tapa Whā model, and the importance of centring land and culture in health interventions. Describing the approach taken by Ihirangi Heke in his work to improve health in sedentary and “overweight” Māori communities, the authors explained:

Heke’s focus was not to ‘help’ people lose weight, but to connect these individuals, all of whom were Māori, to ancestral lands; their mountains, rivers, and forests. In the process, individuals and families came to know these culturally significant locations, which are an inseparable part of cultural identity and health, more intimately. The actual physical activity and subsequent changes in health and weight achieved in the process of ‘reconnecting’ became secondary to a far more meaningful and arguably healthier focus. Presenting physical activity as a means to enhance cultural identity or conversely, cultural identity as a means to enhance physical activity and linkages to significant aspects of ones environment by running up culturally-significant maunga (mountains), and swimming in genealogically relevant awa (rivers) has led to enhanced health and well-being, without focusing individual efforts on weight and weight loss (Warbrick et al., 2015, p. 14).

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have centred the critical health psychology pou of power and equity. We started by discussing distinctions between equality, equity, and social justice, from which, we emphasised the importance of critical reflection on health practice and policy to avoid reproducing inequities and injustice. We then presented important tools for critical reflection from Foucauldian poststructuralist theories, which understand power through the concepts of:

- discourse (relatively coherent ways of understanding an issue, which produce the concept rather than describing something already in existence),

- power as productive, diffuse, and disciplinary,

- power as operating on and through psychology by shaping subjectivity, desire and affect,

- governmentality, in which disciplinary power is leveraged in order to have citizens manage their own behaviour in ways that meet the needs of the state.

Having set up this foundational theoretical framework (and addressing our pou of valuing theoretical/conceptual thinking), we applied it to health, identifying “healthism” as a language of governmentality that:

- produces a narrow construct of health (often related to being slim, White, young or young looking, able bodied, and in full health),

- individualises health as a personal responsibility,

- connects health to consumerism, neoliberal citizenship, and expectations for continuous self-transformation as part of living a good life.

Addressing our pou of challenging taken-for-granted knowledge, our subsequent critique of healthism as a dominant construct of health addressed the question we posed at the beginning of this chapter, namely, “How do our concepts of health shape possibilities for in/equitable health outcomes?”. We did this by showing how healthism makes health hard work, expensive, and risky. It produces a space of anxiety for those who can achieve it, while being out of reach for people with non-normative bodies, including fat and disabled bodies. The optimistic tone of healthism thus easily collapses into a form of cruel optimism, within which shame, anxiety, fear, and stigma circulate.

Having highlighted the limitations of healthism as an individualised construct of health, crystallised in the “personal responsibility” discourse, we finished the chapter through addressing our pou of moving beyond individualism, by considering the importance of:

- critically evaluating discursive constructions, and how they are used in context, for the possibilities they enable and limit

- foregrounding the social, commercial, and digital determinants of health

- holistic constructs of health in Indigenous world views.

Throughout we have addressed our pou of considering knowledge as produced in context, for example, showing how healthism developed into a dominant discourse through multiple intersecting factors, including the responsiblising of citizens within neoliberal economies. This chapter completes our review of foundational thinking in critical health psychology. We have taken you through a lot of ideas, some of which may feel exciting, some may feel overwhelming (maybe both at the same time!).

In the next two chapters we hope to move you fully into an exciting space, as we apply the five pou of critical psychology, and all the associated theoretical work that we have done so far, to understanding how people experience illness (Chapter 1.5) and experience treatment (Chapter 1.6). We also note how the foundational concepts we have covered here will be picked up and developed in Part Two (Approaches to understanding health and illness), and Part Three (Doing critical health psychology).

Knowledge Check

Want to know more?

Watch:

- Leiden University – Faculty of Humanities (Director). (2017, October 19). Chapter 2.5: Michel Foucault, power [Video recording]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=keLnKbmrW5g

- Curtis, A. (Director). (2011). All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace [Video recording]. BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b011lvb9 (also available to watch: https://watchdocumentaries.com/all-watched-over-by-machines-of-loving-grace/)

- Manchanda, R. (2013). What makes us get sick? Look upstream. TED Talk. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/rishi_manchanda_what_makes_us_get_sick_look_upstream

Listen:

- West, S. (2018). Michel Foucault. Philosophize This! [Broadcast]. Retrieved December 11, 2024, from https://www.philosophizethis.org/search?q=foucault

- Gordon, A., & Hobbes, M. (2021). The Body Mass Index. Maintenance Phase [Broadcast]. Retrieved December 11, 2024, from https://www.buzzsprout.com/1411126/episodes/8963468-the-body-mass-index

Read:

- Chapter 2 “Weight”, in Riley, S., Evans, A., & Robson, M. (2019). Postfeminism and health: Critical psychology and media perspectives. Routledge. Available open access at: https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/77181

- The Routledge critical approaches to health book series is produced in association with the International Society for Critical Health Psychology (ISCHP) and covers a range of topics, several of these books are also open access. See the book series website for further details: https://www.routledge.com/Critical-Approaches-to-Health/book-series/CRITHEA

References

1News. (2020, October 13). Judith Collins says obesity is “generally” a weakness, urges personal responsibility over blaming the “system”. https://www.1news.co.nz/2020/10/13/judith-collins-says-obesity-is-generally-a-weakness-urges-personal-responsibility-over-blaming-the-system/

Ann Milne Education. (2021, September 12). That equity image! https://www.annmilne.co.nz/blog/that-equity-image

Arlinghaus, K. R., & Laska, M. N. (2021). Parent feeding practices in the context of food insecurity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020366

Arno, A., & Thomas, S. (2016). The efficacy of nudge theory strategies in influencing adult dietary behaviour: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 676. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3272-x

Bacon, L., & Aphramor, L. (2011). Weight science: Evaluating the evidence for a paradigm shift. Nutrition Journal, 10(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-10-9

Bailey, K. A., Bessey, M., Rice, C., Kelly, E., McHugh, T.-L. F., Punjani, S., Dube, B., Tshuma, P., Besse, K., Sookpaiboon, S., & Quest, S. (2024). In the wake of Canada’s violent eugenic legacies: An urgency to ReVision fitness. Leisure/Loisir, 48(2), 347–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2023.2291033

Bailey, K. A., Griffin, M., Habib, S., Fayyaz, N., Lopez, K. J., & Fudge Schormans, A. (2023). Building community or perpetuating inclusionism? The representation of “inclusion” on fitness facility websites. Leisure/Loisir, 47(4), 659–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2023.2252842

Barnett, P., & Bagshaw, P. (2020). Neoliberalism: What it is, how it affects health and what to do about it. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 133(1512), 76–84. https://nzmj.org.nz/journal/vol-133-no-1512/neoliberalism-what-it-is-how-it-affects-health-and-what-to-do-about-it

Barry, A. (Director). (2015, April 15). Someone else’s country documentary [Video recording]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8PISea_Tc4k

Beck, U. (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity (Vol. 17). Sage Publications.

Berlant, L. (2011). Cruel optimism. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1220p4w

Blumberg, L. J. (2006). The effect of private health insurance coverage on health services utilisation in New Zealand. Fulbright New Zealand. https://fulbright.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/axford2006_blumberg.pdf [PDF]

Breheny, M. (2020, October 15). The tailwind of privilege. International Society of Critical Health Psychology. https://ischp.net/2020/10/15/the-tailwind-of-privilege/

Burgard, D. (2009). What is “health at every size”? In E. Rothblum & S. Solovay (Eds.), The fat studies reader (pp. 42–53). New York University Press. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9780814777435.003.0010

Cairns, K., & Johnston, J. (2015). Choosing health: Embodied neoliberalism, postfeminism, and the “do-diet.” Theory and Society, 44, 153–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-015-9242-y

Calder-Dawe, O., Wetherell, M., Martinussen, M., & Tant, A. (2021). Looking on the bright side: Positivity discourse, affective practices and new femininities. Feminism & Psychology, 31(4), 550–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/09593535211030756

Calogero, R. M., Tylka, T. L., Mensinger, J. L., Meadows, A., & Daníelsdóttir, S. (2019). Recognizing the fundamental right to be fat: A weight-inclusive approach to size acceptance and healing from sizeism. Women & Therapy, 42(1–2), 22–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2018.1524067

Choukou, M. A., Maddahi, A., Polyvyana, A., & Monnin, C. (2021). Digital health technology for indigenous older adults: a scoping review. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 148, 104408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2021.104408

Cobiac, L., Vos, T., & Veerman, L. (2010). Cost-effectiveness of weight watchers and the lighten up to a healthy lifestyle program. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 34(3), 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00520.x

Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (Eds.) (2020). Intersectionality (2nd ed.). John Wiley.

Cooper, C. (2010). Fat studies: Mapping the field. Sociology Compass, 4(12), 1020–1034. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2010.00336.x

Cordes, A., Bak, M., Lyndon, M., Hudson, M., Fiske, A., Celi, L.A., & McLennan, S. (2024). Competing interests: Digital health and indigenous data sovereignty. NPJ Digital Medicine, 7 (178). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01171-z

Crawford, R. (1980). Healthism and the medicalization of everyday life. International Journal of Health Services: Planning, Administration, Evaluation, 10(3), 365–388. https://doi.org/10.2190/3H2H-3XJN-3KAY-G9NY

Crawford, R. (2006). Health as a meaningful social practice. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 10(4), 401–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459306067310

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Curtis, A. (Director). (2011). All watched over by machines of loving grace [Video recording]. BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b011lvb9

Daniel, C. (2020). Is healthy eating too expensive?: How low-income parents evaluate the cost of food. Social Science & Medicine, 248, 112823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112823

Davies, B. (2013). Normalization and emotions. In K. G. Nygren & S. Fahlgren (Eds.), Mobilizing Gender Research: Challenges and Strategies (pp. 123–129). Mid Sweden University. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:646913/FULLTEXT01.pdf#page=31

Davies, B., & Harré, R. (1990). Positioning: The social construction of selves. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.1990.tb00174.x

Durie, M. H. (1985). A Māori perspective of health. Social Science & Medicine, 20(5), 483–486.

Dutta, M. J. (2016). Neoliberal health organizing: Communication, meaning, and politics (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315423531

Edeh, N. A., Riley, S., & Kokot‐Blamey, P. (2022). The production of difference and “becoming black”: The experiences of female Nigerian doctors and nurses working in the national health service. Gender, Work & Organization, 29(2), 520–535. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12779

Fielding-Singh, P., & Dmowska, A. (2022). Obstetric gaslighting and the denial of mothers’ realities. Social Science & Medicine, 301, 114938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114938

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison (A. Sheridan, Trans.). Vintage Books.

Foucault, M. (1978). The history of sexuality (Vol. 1). Pantheon Books.

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings 1972-1977 (C. Gordon, L. Marshall, J. Mepham, & K. Soper, Trans.). Vintage Books.

Foucault, M. (1988). Technologies of the self. In L. H. Martin, H. Gutman, & P. H. Hutton (Eds.), Technologies of the self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault (pp. 16–49). The University of Massachusetts Press. https://philpapers.org/rec/FOUTOT-3

Gailey, J. A. (2022). The violence of fat hatred in the “obesity epidemic” discourse. Humanity & Society, 46(2), 359–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160597621995501

Gard, M. (2010). The end of the obesity epidemic. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203881194

Gavey, N. (2018). Just sex? The cultural scaffolding of rape (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429443220

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Stanford University Press.

Gill, R. (2017). The affective, cultural and psychic life of postfeminism: A postfeminist sensibility 10 years on. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 20(6), 606–626. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549417733003

Gillon, A., & Pausé, C. (2021). Kōrero Mōmona, Kōrero ā-Hauora: A Kaupapa Māori and fat studies discussion of fatness, health and healthism. Fat Studies, 11(1), 8–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/21604851.2021.1906525

Goodman, L. A., Liang, B., Helms, J. E., Latta, R. E., Sparks, E., & Weintraub, S. R. (2004). Training counseling psychologists as social justice agents: Feminist and multicultural principles in action. The Counseling Psychologist, 32(6), 793–836. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000004268802

Graham, K., Treharne, G. J., Ruzibiza, C., & Nicolson, M. (2017). The importance of health(ism): A focus group study of lesbian, gay, bisexual, pansexual, queer and transgender individuals’ understandings of health. Journal of Health Psychology, 22(2), 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105315600236

Graham, R., & Clarke, V. (2021). Staying strong: Exploring experiences of managing emotional distress for African Caribbean women living in the UK. Feminism & Psychology, 31(1), 140–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353520964672

Greenhalgh, T., & Wessely, S. (2004). ‘Health for me’: A sociocultural analysis of healthism in the middle classes. British medical bulletin, 69(1), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldh013

Groot, S., van Ommen, C., Tassell-Matamua, N., & Masters-Awatere, B. (2017). Precarity: Uncertain, insecure and unequal lives in Aotearoa New Zealand. Massey University Press.

Guesmi, H. (2021, April 16). Reckoning with Foucault’s alleged sexual abuse of boys in Tunisia. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/4/16/reckoning-with-foucaults-sexual-abuse-of-boys-in-tunisia

Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199283262.001.0001

Hawaiiki, T. M. M. O., Le Grice, J., Hamley, L., Latimer, C. L., Groot, S., Gillon, A., Greaves, L., & Clark, T. C. (2024). Rangatahi Māori and the whānau chocolate box: Rangatahi wellbeing in whānau contexts. EXPLORE, 20(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2024.05.005

Hochschild, A. R. (1979). Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. American Journal of Sociology, 85(3), 551–575. https://doi.org/10.1086/227049

Hodgetts, D., & Stolte, O. (2017). Urban poverty and health inequalities: A relational approach (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315648200

Hokowhitu, B. (2014). If you are not healthy, then what are you?: Healthism, colonial disease and body-logic. In K. Fitzpatrick & R. Tinning (Eds.), Health education: Critical perspectives (pp. 31–47). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203387993

Hook, D. (2001). Discourse, knowledge, materiality, history: Foucault and discourse analysis. Theory & Psychology, 11(4), 521–547. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354301114006

Hunt, P., & Bradwell-Pollak, S. (2022). Access to vaccines and New Zealand’s distinctive response to COVID-19. Health and Human Rights, 24(2), 215.

Illouz, E. (2007). Cold intimacies: The making of emotional capitalism. Polity Press.

Jahnel, T., Dassow, H.-H., Gerhardus, A., & Schüz, B. (2022). The digital rainbow: Digital determinants of health inequities. Digital Health, 8, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076221129093

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Penguin.

Kashkari, S., & LaMarre, A. (2024). South Asian Muslim individuals’ lived experiences of Type 2 Diabetes healthcare – ‘I just want someone to actually break it down for me.’ Psychology & Health, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2024.2418469