Topic 6: Equity Financing

Introduction

Equity financing is a cornerstone of modern business growth, enabling companies to raise capital by offering ownership in the company in exchange for funding. Equity financing allows companies to attract investors who share in both the risks and rewards of the business. This financing approach is critical for businesses at various stages, from early startups seeking to establish themselves to mature companies looking to expand operations or diversify their portfolios.

A prominent real-life example of equity financing is Amazon’s journey to becoming a global powerhouse. In its early days, Amazon relied on venture capital to fund its growth, securing $8 million from Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers in 1995. Later, in 1997, the company went public through an Initial Public Offering (IPO), raising $54 million by offering shares to the public. As Amazon grew, it also issued Seasoned Equity Offerings (SEOs) to further finance its expansion and fuel innovation. [Footnote 1]

Through this topic, we will explore key aspects of equity financing, including its various forms, the role of venture capital, the significance of IPOs, and the function of seasoned equity offerings.

The key learning outcomes for this topic include:

- Distinguish Between Different Types of Equity – Understand the key differences between private and public equity, as well as common and preference shares, and their implications for businesses and investors.

- Explain Venture Capital and Private Equity – Describe how venture capital supports early-stage businesses, the role of private equity firms, and how these investors provide funding and strategic direction to companies.

- Understand IPOs and Public Equity – Explain the Initial Public Offering (IPO) process, why companies go public, the benefits and challenges of being publicly listed, and how public markets impact corporate financing.

- Analyze Seasoned Equity Offerings (SEOs) – Understand how seasoned equity offerings allow publicly traded companies to raise additional capital, why firms pursue SEOs, and their effects on existing shareholders and market valuation.

Learning Outcome 1: The many different kinds of equity

As explained in the previous topic, equity represents ownership in a company and forms the foundation for raising capital to fuel growth and operations. Businesses utilize various types of equity to meet diverse funding needs and strategic goals. These types include:

- common equity: the basic ownership shares with voting rights.

- preferred equity: which provides fixed dividends and priority in liquidation

- private equity: held by a select group of investors or

- public equity: traded on stock exchanges and accessible to the general public.

Each type serves distinct purposes, from early-stage funding to corporate expansions, reflecting the dynamic nature of equity financing.

1.1 Common vs. Preferred Equity

Common equity and preferred equity are two primary forms of equity that companies issue to raise capital. While both represent ownership in a company, they differ significantly in terms of rights, benefits, and risks.

Common equity (also known as common shares) represents the basic ownership in a company and held by common shareholders. These shareholders typically have the right to vote on key corporate matters, such as electing the board of directors. In case of liquidation, common shareholders receive assets only after all debts and preferred shareholders are paid (that is they are residual claimants on the firm’s assets). Common shareholders benefit directly from the company’s growth, as their returns are tied to stock price appreciation and dividends. These two forms of return: share price increase and dividends are the main reason why investors invest in equity. However, there is risk involved in investing in equity as returns are not guaranteed, and in the cases of financial distress or bankruptcy, common shareholders may receive nothing and lose their entire investment in the company.

Preferred equity (also known as preferred shares or preference shares) is a hybrid form of equity that combines features of both equity and debt, offering specific privileges over common equity. These privileges include priority in dividends, at a fixed dividend rate such as 8% of the par value, and priority in liquidation, should the company encounter bankruptcy. However, most preference shares have limited or no voting rights and hence restrict preference shareholders’ involvement in business operations. A major advantage of preference shares over common shares is fixed dividends provide a more predictable income stream. However, preferred shareholders typically do not benefit from the company’s growth to the same extent as common shareholders, as their returns are fixed.

The below table summarizes key differences between these two types of equity.

| Common Equity | Preferred Equity | |

|---|---|---|

| Ownership | Basic ownership with full voting rights. | Hybrid ownership with limited or no voting rights. |

| Dividends | Variable, dependent on company profits. | Fixed and paid before common dividends. |

| Risk | Higher risk with potential for high returns. | Lower risk with stable but limited returns. |

| Liquidation Priority | Paid last after all obligations. | Paid before common shareholders. |

| Growth Potential | Benefits from stock price appreciation. | Limited growth potential due to fixed returns. |

From an investor point of view, common equity is ideal for investors seeking high growth and a voice in corporate decisions, while preferred equity suits those prioritizing stable returns and lower risk.

1.2 Private vs. Public Equity

Private equity represents ownership stakes in private companies that are not publicly traded on stock exchanges. It is typically held by a limited number of private investors, such as institutional investors or high-net-worth individuals. As the companies are private, shares are not easily bought or sold; and private equity investments often require long-term commitments before investors can realize their return.

A major source of private equity is private equity funds. These private equity (PE) funds are investment vehicles that pool capital from institutional investors, high-net-worth individuals, and sometimes sovereign wealth funds to invest in privately held companies. These funds are managed by private equity firms and are designed to achieve substantial returns by taking ownership stakes in companies and actively managing them to increase value over time. Investments are normally held for 5–10 years, during which the PE firm works to increase the company’s value. PE funds realize returns through methods such as selling the company, conducting an IPO, or merging with another company. The focus of PE funds is primarily:

- Venture Capital: investments in startups or early-stage companies

- Growth Capital: investments in established companies seeking growth capital.

- Buyouts Capital: investment in underperforming companies that require restructuring

A well-known example is Blackstone Group, one of the largest private equity firms globally, which has used its funds to acquire and transform businesses worldwide. In Australia, one of Blackstone’s largest investments is Crown Resorts which it acquired in 2022 for $A8.9 billion. [Footnote 2] The aim of Blackstone in this investment is to improve the management of the company and generate returns for its investors.

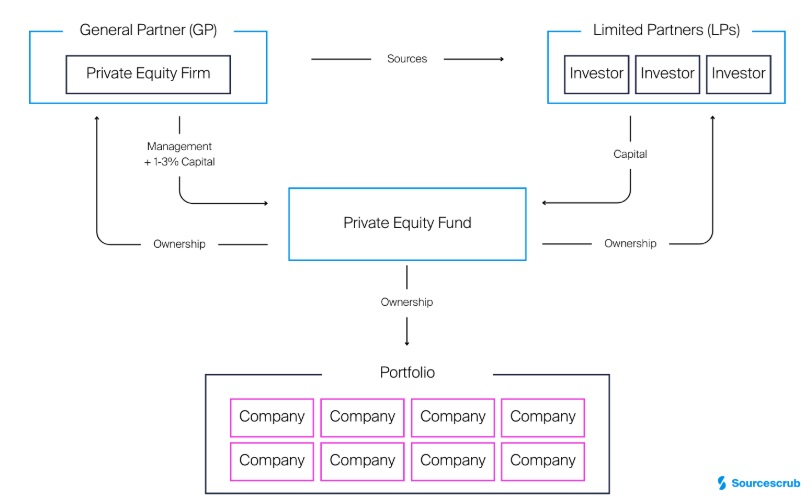

Most PE funds operate as limited partnerships (LPs) comprising of two types of partners:

- General Partners (GPs): The private equity firm manages the fund, selects investments, and oversees portfolio companies. These GPs may contribute a small share of capital of approximately 10% and receive a 20% share of the profits plus a management fees.

- Limited Partners (LPs): Institutional investors or individuals who provide the majority of the capital but have limited liability and no active role in management. LPs typically contribute the majority (90%) of the capital and receive the majority of the profits (80%) as a return on their investment.

The structure of a PE fund is illustrated graphically below

Private equity funds play a vital role in the financial ecosystem by providing critical funding and expertise to businesses, driving innovation and growth in startups and rescuing and restructuring struggling companies to restore profitability.

While offering potentially high returns, these funds are generally accessible only to sophisticated investors due to the high-risk, long-time horizon, and significant capital requirements involved.

Public Equity represents ownership in companies that are publicly traded on stock exchanges such as the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX). For these listed companies, shares are distributed among a broad base of public investors which comprise of both institutional and retail investors and can be freely bought and sold on the stock market, offering high liquidity. Due to the broad investor base, publicly listed companies are subject to strict regulatory and reporting requirements imposed by the stock exchanges as per the listing rules. Public equity offers liquidity, transparency, and accessibility, making it a suitable option for a wider range of investors.

The table below provides a summary of the key differences between private and public equity.

| Private Equity | Public Equity | |

|---|---|---|

| Ownership | Limited to private investors (e.g., private equity firms). | Broadly distributed among the public. |

| Access to Shares | Restricted; requires private agreements. | Freely accessible on public stock exchanges. |

| Liquidity | Low; investments are long-term and difficult to sell. | High; shares can be traded daily on the market. |

| Regulation | Minimal disclosure requirements. | Highly regulated with mandatory disclosures. |

| Investment Stage | Often targets startups, early-stage, or distressed companies. | Targets mature companies seeking broader capital. |

| Transparency | Limited visibility into business operations. | High transparency due to public reporting standards. |

| Returns | Potential for high returns due to early or turnaround investments but higher risk. | Returns depend on market performance and dividends. |

1.3 Life cycle analysis of equity financing

The firm life cycle refers to the stages a business typically goes through as it grows, matures, and evolves over time. Each stage is characterized by distinct challenges, opportunities, and financing needs, influencing the firm’s strategy, operations, and access to capital. Understanding the firm life cycle helps businesses anticipate and adapt to changes, ensuring sustainable growth and long-term success. The key stages of the firm life cycle are:

- Start-Up Stage: The business is in its infancy, focusing on developing a product or service, building a customer base, and establishing a market presence. In this stage, the company has a high level of risk, limited resources, and uncertainty about market acceptance.

- Growth Stage: The firm experiences rapid revenue and market expansion, scaling operations to meet growing demand. The major challenges for the company during this phase is to manage growth, hire talent and expand its infrastructure while maintaining the quality of its products and services.

- Maturity Stage: The firm reaches a stable position, with consistent revenues, established market share, and operational efficiency. During this stage, the company is still growing but at a much slower rate. It faces competition and pressure to innovate.

- Decline or Renewal Stage: The firm faces stagnation or decline due to market saturation, outdated products, or operational inefficiencies. Alternatively, it may pursue renewal through innovation or diversification to remain relevant in the marketplace.

As a firm progresses through its life cycle, it has varying funding needs and can access different types of equity tailored to its evolving needs and growth stages. The type of equity available to the company at different stages in its life is presented in the table below.

| Life Cycle Stage | Funding Needs | Type of Equity Available |

|---|---|---|

| Start-Up Stage | – Product development – Initial operations – Building a customer base |

– Seed Funding: Early investments from founders, friends, or family. – Venture Capital: Investments in exchange for equity (PE funds or angel investors). |

| Growth Stage | – Scaling operations – Market expansion – Hiring talent – Infrastructure development |

– Private Equity: Growth capital from private equity firms. – Convertible Equity: Convertible bonds or preferred shares that can be converted into common equity. – Strategic Partnerships: Equity funding from corporate investors. |

| Maturity Stage | – Sustaining growth – Diversifying product lines – Expanding to new markets |

– Public Equity: Issuance of shares through an Initial Public Offering (IPO). – Seasoned Equity Offerings (SEOs): Additional shares issued to raise funds. |

| Decline/Renewal Stage | – Restructuring operations – Innovation – Addressing competition or market shifts |

– Private Equity Buyouts: Equity sold to private equity firms for turnaround financing. – Seasoned Equity Offerings (SEOs): Additional public equity to fund restructuring or innovation. – Convertible Equity: Used to attract investors during high-risk stages. |

Learning Outcome 2: Venture Capital and Private Equity

2.1 What is Venture Capital?

Venture capital (VC) is a form of private equity financing that provides funding to early-stage, high-growth startups in exchange for an ownership stake. Venture capital firms and investors invest in companies that have strong growth potential but may not yet be profitable or able to secure traditional bank loans or other forms of borrowings.

Venture capitalists are investors who provide funding to early-stage, high-growth startups in exchange for equity. They can be individuals, venture capital firms, or investment groups that specialize in identifying and backing promising businesses with strong potential for scalability. Venture capitalists typically come from backgrounds in finance, entrepreneurship, or technology and often have industry expertise that helps them assess business opportunities. They do more than just provide capital—they also offer strategic guidance, mentorship, and access to their professional networks to help startups succeed.

A well-known example of a company that received venture capital funding is Canva, the Australian graphic design platform.

Canva secured early-stage funding from Blackbird Ventures, an Australian venture capital firm known for backing high-growth startups. As the company scaled, it attracted investments from prominent global VC firms, including Sequoia Capital, Felicis Ventures, and Bessemer Venture Partners. These firms provided capital across multiple funding rounds, helping Canva expand its product offerings and global reach.

Through strategic VC backing, Canva grew from a startup to a multi-billion-dollar unicorn and is now one of Australia’s most successful tech companies. This highlights how venture capital helps innovative businesses scale and achieve international success.

2.2 Characteristics of a venture capital investment

Equity investments in general are inherently risky, but venture capital investments carry an extremely high level of risks with a promise of an extremely high level of returns if/when the startups succeed.

Major characteristics of a venture capital investment is as follows:

- Equity-Based Investment: Venture capitalists provide funding in exchange for an equity stake (ownership) in the company, rather than a loan that requires repayment.

- Focus on High-Growth Startups: VC firms invest in early-stage, high-potential companies, often in technology, biotech, and other innovative sectors.

- High Risk, High Return: Since startups have uncertain futures, venture capital is considered high-risk, but successful investments can yield massive returns through potential IPOs or acquisition by another company.

- Active Involvement & Mentorship: VCs provide more than just capital; they offer strategic guidance, mentorship, and industry connections to help startups grow.

- Long-Term Investment Horizon: Venture capitalists typically expect a 5–10 year investment period before they see returns through an exit strategy like an IPO or acquisition.

- Exit-Driven Strategy: The ultimate goal of venture capital is to generate high returns through a profitable exit, usually by selling shares in an IPO or through a corporate acquisition.

- Portfolio Approach: Since many startups fail, VCs diversify investments across multiple companies, hoping that a few big successes will outweigh the losses.

- Preference for Disruptive & Scalable Businesses: VCs target companies with innovative business models and strong potential for scalability in large markets.

2.3 Stages of Venture Capital Funding

Venture capital firms typically provide funding in stages to manage risk, ensure startups meet growth milestones before additional funding can be provided, and optimize their investment strategy. This approach allows VCs to allocate capital efficiently, reducing the chances of heavy losses while maximizing potential returns.

Each round/stage of venture capital funding serves a different purpose in a startup’s growth. As companies progress, they raise additional funding at higher valuations to scale operations, expand market reach, and eventually achieve an exit (IPO or acquisition).

- Seed funding: Seed funding is provided at an early development stage to help validate the startup’s business idea and model before scaling. It’s typically used to develop a prototype, conduct market research and build an initial team. As an example, Canva raised $3 million in seed funding from Blackbird Ventures and Matrix Partners in 2013 to refine its product before launching.

- Series A funding: This type of funding is used to scale the business after the business meets certain performance milestones such as revenue, subscriber number etc after the seed funding stage. The funding from Series A can be used for marketing, recruiting talent or improving technology. Airtasker (an Australian task marketplace) raised $6.5 million in Series A from Exto Partners and Morning Crest Capital to expand operations in 2016.

- Series B funding: Companies can proceed to Series B funding after they successfully build a scalable business and sizeable customer base. Series B funding can support rapid expansions, business development and entry into new markets.

- Series C funding: This is typically the last stage of venture capital funding as the business has reached a level of maturity that prepares them for the next step of funding such as an IPO. Series C funding is used for large scale expansions, acquisitions of other businesses or preparation for an IPO.

Each funding stage supports a startup’s journey from idea to global expansion. Investors participate at different points based on risk tolerance and return expectations, ensuring that capital is deployed effectively as the company grows.

2.4 Importance of Venture Capital

Venture capital (VC) plays a crucial role in driving innovation and economic growth by funding early-stage companies that have the potential to disrupt industries. Many of the world’s largest and most successful companies, including Amazon, Google, Facebook (Meta), and Tesla, were initially backed by venture capital firms.

For example, Google received early funding from Sequoia Capital and Kleiner Perkins, which helped it scale its search engine technology and expand into a global tech giant.

Similarly, Facebook secured investment from Accel Partners in its early days, allowing it to grow rapidly and dominate the social media space.

Tesla, now a leader in electric vehicles, was supported by Draper Fisher Jurvetson (DFJ), which provided the capital needed to develop cutting-edge battery and automotive technology.

Without venture capital, many of these companies would have struggled to secure the funding necessary for research, development, and global expansion. By taking on high-risk investments in startups, VC firms fuel innovation, create jobs, transform entire industries and contribute to economic growth.

Learning Outcome 3: Initial Public Offerings and Public Equity

3.1 What is an Initial Public Offering (IPO)

An Initial Public Offering (IPO) is the process by which a private company offers shares to the public for the first time. In this process, the company gains access to public equity and allows it to be listed on a stock exchange such as the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX), the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) or National Association of Security Dealers Automated Quotations (NASDAQ).

A company is ready for an IPO when it has reached a level of maturity, financial stability, and market demand that justifies going public. Several key factors determine whether a business is prepared for this major transition including financial performance and revenue growth. Companies are also more likely to go public when market conditions are favourable ie. during market upswing with strong investor confidence as they are more likely to succeed in those conditions.

3.2 Why companies go public

Companies choose to go public through an Initial Public Offering (IPO) to raise significant capital, enhance their market presence, and provide liquidity for early investors.

One of the primary motivations is access to large-scale funding. By issuing shares to the public, companies can raise substantial capital that can be used for expansion, acquisitions, research and development, or debt reduction. Unlike debt financing, where loans must be repaid with interest, IPO funding does not require repayment, allowing companies to invest in long-term growth without immediate financial pressure.

Going public also enhances a company’s market visibility and credibility. Being listed on a stock exchange increases brand recognition, improves customer and partner confidence, and can attract more business opportunities.

Additionally, an IPO provides liquidity for early investors and employees who have equity in the company. Venture capital firms, private equity investors, and founders can sell their shares and realize returns on their early investments. Employees with stock options also gain the ability to convert their equity into cash, which can help attract and retain top talent.

While an IPO brings benefits, it also comes with risks such as increased scrutiny, regulatory compliance, and market volatility. Therefore, companies must weigh the long-term advantages against the challenges before deciding to go public.

3.3 The IPO Process

The IPO process involves several stages, from preparing the company for public scrutiny to listing on a stock exchange. It is a complex process that typically takes several months and requires coordination between investment banks, regulators, and financial advisors.

Once the decision to go public is made, the IPO process generally involves the following steps:

- Selecting an investment bank to work as the underwriter: The company usually hires investment banks to manage the IPO, set the share price, and attract investors. These banks act as underwriters, meaning they buy the shares from the company and resell them to investors. For a small issue, the company may hire just one investment bank to help with the issue. For larger issues, such as the Facebook’s IPO in 2012 that raised approximately US$16 billion, a group of investment banks can all be appointed as underwriters creating an underwriting syndicate. An underwriter plays a crucial role in an IPO by managing the entire process, ensuring the company successfully transitions from private to public ownership. The IPO company chooses an underwriter or underwriter syndicate based on quality of the investment banks research and marketing teams, geographical expertise, investor client base/distribution networks, industry reputation as well as any prior dealings the company may have had with particular banks.

- Due diligence and regulatory filings: The company, along with auditors and legal teams, prepares the prospectus, a legal disclosure document that provides information about the share offering to the public. The prospectus typically details the company’s financial performance, risks, business model, and future plans. Once completed, the prospectus is submitted to regulators for approval. In Australia, it goes to the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC) for an ASX listing.

- Roadshow and marketing: The company and underwriters go on a roadshow which is a series of meetings with institutional investors such as hedge funds and mutual funds to generate interest and estimate demand for the shares. This phase helps determine the final IPO price based on investor appetite. Roadshow can sometimes be referred to as the bookbuilding process as this activity allows the issuing company to “build a book” of potential orders from institutional inventors.

- Setting the IPO price and share allocation: Based on investor demand from the roadshow, underwriters determine the final IPO price and the number of shares to be sold to public investors. They will also determine how shares are allocated between institutional and retail investors.

- IPO day: On IPO day, shares that investors subscribe to are released and they can be traded on the stock exchange. The stock price may fluctuate significantly on the first day based on market demand and investor sentiment. When the closing share price after the first day of trading is greater than the IPO price, the issue is said to be “underpriced”. In the opposite situation, it is “overpriced”.

An IPO is considered successful when the company can sell all the intended shares to the public without being significantly “underpriced”. The proceeds that the company receives from selling each share is slightly less that what the investors have to pay to reflect a spread, which represents the return to the underwriters to compensate them for the work that they do.

3.4 IPO Success Determinants

Empirical research highlights five critical factors that determine the success of an IPO.

- Financial Performance and Transparency: Companies exhibiting consistent revenue growth and clear financial reporting instill confidence among investors, enhancing IPO success.

- Unique Business Model: A distinctive and scalable business model with a clear competitive advantage makes a company more attractive to investors during an IPO.

- Experienced Management Team: A seasoned leadership team with a proven track record assures investors of effective company stewardship and strategic execution, which are vital for post-IPO success.

- Accurate IPO Pricing Strategy: Setting an appropriate IPO price is essential; overpricing can deter investors, while underpricing may lead to capital shortfalls.

- Favourable Market Conditions and Timing: Launching an IPO during periods of market stability and positive economic indicators can enhance the likelihood of success, as investor sentiment is more likely to be optimistic.

Empirical data supports the impact of market conditions on IPO activity. For instance, in 2024, the U.S. IPO market experienced a resurgence, raising over $41 billion, up from $24 billion in 2023 and $22 billion in 2022. This increase coincided with favourable market conditions, including declining interest rates and positive investor sentiment. [Footnote 3]

Conversely, during bear markets, IPO activity tends to decline. Economic uncertainty and declining stock prices make investors cautious, leading to reduced interest and lower valuations for IPO companies.

Learning Outcome 4: Season Equity Offerings

While an IPO marks a company’s first sale of shares to the public, many firms later raise additional capital through Seasoned Equity Offerings (SEOs). An SEO occurs when a publicly traded company issues new shares to investors, either to fund expansion, pay down debt, or strengthen its financial position.

Unlike IPOs, SEOs are available only to companies that are already listed on a stock exchange. The success of an SEO, much like an IPO, depends on factors such as market conditions, investor confidence, and the company’s financial health. For instance, companies with a strong business model and a history of profitability tend to attract more investor interest when issuing additional shares. Market conditions also play a crucial role—firms often conduct SEOs when stock prices are high and investor sentiment is strong, maximizing the capital they can raise.

Recent IPO trends show that many newly listed companies later turn to SEOs to fuel further growth, highlighting how public equity financing remains a key strategic tool beyond the initial public listing.

The Seasoned Equity Offering (SEO) process is similar to an IPO but involves a publicly traded company issuing additional shares to raise capital. Like an IPO, the process includes hiring underwriters, filing regulatory documents, determining pricing, marketing to investors, and executing the offering. However, a key difference is that SEO regulations allow for faster approval since the company is already listed and has an established track record. In Australia, companies must notify the ASX and comply with Listing Rule 7.1, which limits how many shares can be issued without shareholder approval.

SEOs can be primary (new share issuance, diluting existing ownership) or secondary (existing shareholders selling shares, with no dilution). Companies often conduct SEOs when market conditions are favorable, stock prices are high, and investor confidence is strong to maximize capital raised while minimizing dilution effects. Post-offering, firms must comply with ongoing financial reporting and market disclosures, similar to IPO requirements.

SEOs can be structured in different ways, depending on the target investors, regulatory considerations, and the company’s financial strategy. The three main types are Public Offerings, Rights Issues, and Private Placements.

4.1 Seasoned Equity Public Offerings

In a seasoned equity offering, companies typically issue new shares to the general public. The process of issue is similar to an IPO as highlighted above.

A key consideration for existing shareholders in a company that decides to undertake a seasoned equity public offering is dilution. Dilution is the situation when the total number of outstanding shares increases, reducing the ownership percentage of existing shareholders.

Dilution Example

Suppose a company currently has 100 million shares outstanding, and its stock is trading at $50 per share. The company’s market capitalization (total value of shares) is:

100 million shares × $ 50=$5 billion

Now, the company decides to raise $1 billion through a public seasoned equity offering by issuing additional shares. If the company prices the new shares at a 10% discount to attract investors, the offering price would be:

50 × 0.90=45 dollars per share

The number of new shares issued will be:

45 dollars per share/1 billion dollars=22.22 million new shares

After the offering, the total number of shares outstanding increases from 100 million to 122.22 million. Each existing shareholder now owns a smaller percentage of the company.

For example, if an investor previously owned 1 million shares, their ownership percentage before the offering was:

100 million=1%

After the offering, their new ownership percentage is:

1 million/122.22million=0.82%

This dilution means the investor owns a smaller share of the company, which could affect their proportional earnings and voting power.

Additionally, the earnings per share (EPS) may decrease if the capital raised does not immediately generate equivalent profit growth.

Due to the potential dilution effect, in Australia, companies listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) must adhere to Listing Rule 7.1, which limits the number of new shares a company can issue without shareholder approval to 15% of existing capital within a 12-month period. This rule is designed to protect shareholders from excessive dilution of their holdings.

The pricing of a public seasoned offering is a critical factor in its success. Unlike an Initial Public Offering (IPO), where pricing is based on market demand and company valuation, a SEPO’s price is influenced by the company’s existing stock price, market conditions, and investor sentiment. Companies often issue shares at a discount to the market price to attract investors and ensure demand. For example, in the above example, the shares were issued at a 10% discount compared to the market price. However, excessive discounts can signal financial distress, leading to negative market reactions.

4.2 Equity Rights Issue

A rights issue is a form of Seasoned Equity Offering (SEO) in which a publicly traded company offers existing shareholders the right to purchase additional shares at a discounted price, usually in proportion to their current holdings. This method allows companies to raise capital while giving existing investors the opportunity to maintain their ownership percentage and avoid dilution. Unlike a public issue, where new shares are sold to the general public, a rights issue is restricted to current shareholders.

Additionally, rights issues often have subscription rights, meaning shareholders can choose to exercise their right to buy more shares, sell their rights to other investors, or let them expire. A key difference is that public issues aim to attract new investors and expand ownership, whereas rights issues prioritize protecting existing shareholders’ stakes. Public issues may also involve underwriters who guarantee the sale of shares, whereas rights issues may be partially or fully underwritten depending on the company’s strategy. While both methods raise capital, a rights issue is generally used when a company wants to strengthen its balance sheet without significantly altering its shareholder base.

To understand the mechanism of a rights issue, consider the following numerical example.

Suppose you own 1,000 shares of Wobble Telecom, each trading at $5.50. The company announces a rights offering to raise capital, offering 10 million new shares at a subscription price of $3 per share. The rights issue is structured as a 3-for-10 offer, meaning you can purchase 3 additional shares for every 10 shares you currently own.

Step 1 – Calculating the Theoretical Ex-Rights Price (TERP)

- Total value of existing shares = 1,000 shares × $5.50 = $5,500

- Total cost to purchase new shares = 300 shares × $3 = $900

- Combined value of shares = $5,500 (existing shares) + $900 (new shares) = $6,400

- Total number of shares after rights issue = 1,000 (existing) + 300 (new) = 1,300 shares

Hence, the price of each share after the rights issue should theoretically be:

-

- $6,400 ÷ 1,300 shares = $4.92 per share

Step 2 – Calculating the Value of a Right

The value of one right is determined by the difference between the TERP and the subscription price:

- $4.92 (TERP) – $3 (subscription price) = $1.92 per right

Therefore, each right has a theoretical value of $1.92. As a shareholder, you can choose to exercise your rights to maintain your ownership percentage or sell the rights to other investors. This example demonstrates how rights issues provide existing shareholders with the opportunity to purchase additional shares at a discount, while also illustrating the potential dilution effect if the rights are not exercised.

4.3 Private Placement

A private placement is a method of raising equity capital by selling shares directly to a select group of investors rather than through a public offering. These investors typically include institutional investors, such as banks, insurance companies, superannuation funds, or high-net-worth individuals.

Unlike public offerings, private placements are not required to be registered with regulatory bodies like the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) or the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), making the process faster and less costly.

However, this also means that private placements are subject to fewer disclosure requirements, which can limit transparency. Companies often use private placements as an alternative to traditional public offerings when they want to raise funds quickly, maintain control over their shareholder structure, or avoid market fluctuations.

Private placements are typically priced based on a discount to the prevailing market price of the company’s shares or securities. The discount is offered as an incentive to attract investors and is determined by several factors, including the size of the placement, the company’s financial health, market conditions, and investor demand. In some cases, pricing is based on a VWAP (Volume-Weighted Average Price) over a specified period to ensure fairness and avoid price manipulation.

A company can conduct a private placement alongside a retail offer as part of a capital-raising strategy to ensure fairness between institutional and retail investors. This often occurs in capital raisings that involve an institutional placement followed by a share purchase plan (SPP) or rights issue for retail investors. This dual structure allows the company to quickly secure funds from institutional investors while ensuring that retail investors also have the opportunity to participate in the capital raising on similar terms.

When a company raises capital through a private placement without offering retail investors a similar opportunity to participate, it can lead to dilution of existing shareholders’ ownership. This occurs because new shares are issued to institutional or high-net-worth investors, increasing the total number of shares on issue. As a result, the percentage ownership of existing shareholders decreases, potentially reducing their voting power and claim on future earnings and dividends.

The dilution effect is particularly pronounced if the private placement is conducted at a discount to the prevailing market price, as this effectively transfers value from existing shareholders to the new investors. If a significant amount of equity is raised through a placement, existing shareholders who are not given the opportunity to participate may see a reduction in their relative stake in the company.

To prevent excessive dilution, many stock exchanges and regulators impose limits on the amount of equity a company can issue through private placements within a given period. In Australia, under ASX Listing Rule, a company can issue up to 15% of its shares in any 12-month period via private placement without needing shareholder approval. [Footnote 4]

Summary – Key Concepts in this Topic

1. Different Kinds of Equity: Equity represents ownership in a company, and there are various types including common vs. preferred equity, private vs. public equity. The type of equity that a firm has access to depends on where it is in its life cycle.

2. Venture Capital and Private Equity: Venture Capital is a type of private equity and specifically targets early-stage investment in startups with high growth potential. VC firms provide funding in exchange for equity and often take an active role in management.

3. IPO (Initial Public Offering) and Public Equity: A company can access public equity through an IPO. IPO refers to the first time a company offers its shares to the public on a stock exchange to raise capital. This provides liquidity to early investors and allows broader ownership. Following an IPO, shares traded on public markets, allowing any investor to buy and sell ownership stakes. Companies must comply with disclosure and regulatory requirements to maintain transparency.

4. Seasoned Equity Offerings (SEOs): Any subsequent equity issue undertaken by a public company is referred to as a SEO. There are a few different ways in which a company can conduct an SEO including: a public offering, a rights issue or a private placement. Each type of SEO issue has its own advantages and disadvantages that the company needs to consider thoroughly before making a decision that is best for the company and its sha

Footnotes

- For more details, see https://www.fundable.com/learn/startup-stories/amazon

- For more details, see Where I’m putting the money: Blackstone’s Australian investments

- For more details, see investopedia.com

- For more details, see Public companies in Australia raising capital by Hamilton Locke