Topic 5: Capital Structure and Cost of Capital

Introduction

In capital budgeting, accurately estimating the cost of capital is critical to assessing project risk and determining the Net Present Value (NPV) or Internal Rate of Return (IRR). A company’s cost of capital is directly influenced by its capital structure and these two concepts are the focus of this topic.

Capital structure refers to the mix of debt and equity a company uses to finance its operations and investments, while cost of capital is the rate of return required by investors and lenders to fund these activities. As explained in the last topic, this cost of capital plays a central role in capital budgeting as it serves as the discount rate used to evaluate the viability of long-term investment projects.

Capital structure is directly related to the financing decision, the second key area of corporate financial decision-making. The financing decision focuses on determining how a company will fund its operations and investments by choosing an appropriate mix of debt and equity. Capital structure represents the outcome of this decision, reflecting the proportions of these funding sources.

An optimal capital structure balances the benefits and costs of debt and equity, minimizing the company’s overall cost of capital while managing financial risk. For example, using debt can be advantageous due to tax-deductible interest payments, but excessive reliance on debt increases the risk of financial distress. Equity, while more expensive, provides flexibility and reduces default risk. The financing decision ensures that the capital structure aligns with the company’s strategic objectives, risk tolerance, and market conditions, ultimately influencing its ability to achieve sustainable growth and value creation.

The key learning outcomes for this topic include:

- Understand the Main Sources of Financing: Identify and explain the primary sources of financing available to companies, including debt (e.g., loans, bonds) and equity (e.g., retained earnings, issuing shares). Discuss the advantages, disadvantages, and suitability of each financing source based on business needs and market conditions.

- Comprehend the Concept and Measures of Capital Structure: Define capital structure and its role in corporate finance. Understand how to measure a company’s capital structure using financial ratios such as the debt-to-equity ratio, debt ratio, and equity ratio. Explore how these measures provide insights into a company’s financial health and risk profile.

- Explore Capital Structure Theories: Examine key theories of capital structure, including the Modigliani-Miller theorem, the trade-off theory, the pecking order theory, and the agency theory. Analyse how these theories guide decision-making and the implications of choosing between debt and equity financing.

- Estimate the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC): Learn how to calculate the WACC as a function of the costs of debt and equity and their respective proportions in the capital structure. Understand the significance of WACC in evaluating investment opportunities, serving as the discount rate in capital budgeting, and its impact on corporate valuation.

Learning Objective 1 - Characteristics of Equity and Debt

Debt and equity are the two primary sources of finance for a company, each with distinct characteristics, advantages, and implications for decision making.

1. 1 Equity Financing

When a company raises funds through equity, it typically does so by issuing ordinary shares (common stock) during an initial public offering (IPO) in the capital market. In an IPO, investors purchase the newly issued shares, providing the company with the capital generated from the total sale of those shares. This capital becomes part of the company’s equity, which can then be used to finance operations, growth initiatives, or other strategic objectives.

Equity possesses the following characteristics

- Residual Claim: Dividend payments to ordinary shareholders are discretionary, meaning they are only distributed after a company has fulfilled its financial obligations to all other claimants, including suppliers, employees (wages and salaries), lenders (debt and interest payments), and the government (taxes). In the event of liquidation, ordinary shareholders have a residual claim on the proceeds from the sale of the company's assets, after all prior obligations are settled. Because ordinary shareholders bear the highest risk, they expect a higher return compared to debt investors.

- Not Tax-Deductible: Dividend payments made to shareholders are not tax-deductible for the company, unlike interest payments on debt. As a result, the company does not receive any tax benefit from using equity financing.

- Infinite Maturity: Ordinary shares have no maturity date, meaning they remain outstanding as long as the company operates and is listed on the stock exchange. Shareholders cannot "cash in" their shares with the company directly but can sell them in the secondary market.

- Dividend Entitlement: Shareholders are entitled to a proportional share of any dividends declared by the company’s board of directors. However, these payments are not guaranteed and depend on the company's profitability and financial policy.

- Management Control: Ordinary shareholders hold voting rights that allow them to influence the management of the company. They typically have the right to vote on significant matters, such as electing members to the board of directors, granting them some control over the company's operations. Generally, each share held corresponds to one vote.

- Liquidity in the Secondary Market: Ordinary shareholders have the right to sell their shares on the stock exchange, providing liquidity. This allows them to exit their investment without requiring the company to repurchase the shares.

From the point of view of the company, there are a number of advantages associated with equity as a form of financing.

- Discretionary Dividend Payments: The company is not obligated to pay dividends to ordinary shareholders; dividend payments are made at the discretion of the board of directors.

- No Maturity Obligation: Ordinary shares have no maturity date, meaning the issuing company is under no obligation to redeem them, and they remain outstanding indefinitely as long as the company operates.

- Impact on Debt Financing Costs: A higher proportion of equity in a firm's capital structure reduces the risk to lenders, as equity serves as a buffer against potential losses. This lower risk can result in reduced interest rates on debt financing, decreasing the overall cost of borrowing for the company.

However, there are also disadvantages of this form of financing which include:

- Legal Claim and High Priority in Financial Distress: Borrowers are obligated to make regular interest payments and repay the principal amount to lenders as agreed. In the event of default, lenders have legal recourse to recover their funds. For secured loans, this may involve taking possession of pledged assets, while unsecured loans may lead to legal action against the borrower.

- Tax-Deductible Interest: Interest expenses incurred on debt are tax-deductible, providing a tax shield that reduces the company's taxable income. For instance, if a company pays $1,000,000 in annual interest and the corporate tax rate is 30%, it saves $300,000 in taxes (30% of $1,000,000). This tax benefit lowers the effective cost of debt financing.

- Fixed Maturity: Debt typically comes with a specified maturity date by which the principal amount must be fully repaid. For example, a 10-year $10,000 bond issued on April 1, 2017, will mature on April 1, 2027, requiring repayment of the full $10,000 at that time.

- No Direct Management Control: Lenders generally do not have control over a company's operations as long as the borrower meets its debt obligations. However, if the company defaults, lenders can exert significant influence, such as seizing pledged assets, appointing an administrator, or placing the company into receivership or liquidation. While lenders lack direct management control, their potential control in cases of default is considerable.

Debt financing can be an attractive financing option for companies due to the following advantages:

- Tax Benefits: One of the most significant advantages of debt is that interest payments are tax-deductible, reducing the company’s taxable income and providing a tax shield. This lowers the effective cost of borrowing, making debt a cost-efficient source of financing.

- Retained Ownership and Control: Unlike equity financing, debt does not dilute the ownership of existing shareholders. The company retains full control over its operations as long as it meets its debt obligations, preserving shareholder influence and decision-making authority.

- Predictable Cost: Debt financing involves fixed interest payments and a predefined repayment schedule, providing predictability in financial planning. This makes it easier for companies to forecast expenses and manage cash flows.

- Leverage Benefits: Properly structured debt can enhance returns for equity holders. By leveraging borrowed funds to finance profitable projects, a company can increase its return on equity (ROE), magnifying shareholder value.

The major issue with using debt is it leads to increased financial risk which manifest when the company is unable to make the payment obligations. Due to the financial risk associated with borrowing, companies that have a high level of borrowing may experience:

- Potential Loss of Assets: For secured debt, lenders may seize pledged assets in the event of default, which can severely impact the company’s operations and financial stability.

- Higher Cost of Borrowing with Increased Debt: As the company takes on more debt, lenders may perceive a higher risk of default and demand higher interest rates, increasing the overall cost of borrowing.

- Impact on Credit Rating: Excessive debt can negatively affect the company’s credit rating, making it more difficult and expensive to secure additional financing in the future.

Learning Objective 2: Concept and Measure of Capital Structure

2.1 What is Capital Structure?

As previously explained, capital structure refers to the mix of debt and equity a company uses to finance its operations, growth, and investments. This mix is critical because it influences the company’s overall cost of capital, financial risk, and ability to generate returns for stakeholders. Companies strive to achieve an optimal capital structure that minimizes the cost of financing while maximizing shareholder value. However, the composition of debt and equity varies significantly between companies due to several internal and external factors. These factors, known as the determinants of capital structure, help explain why different companies may adopt different financing strategies.

Some important determinants of capital structure include:

- Nature of the Business:

- Companies in stable and asset-intensive industries, like utilities, often use more debt because of predictable cash flows that support regular interest payments.

- Conversely, firms in volatile or growth-oriented sectors, like technology, prefer equity to avoid fixed repayment obligations.

- Profitability:

- Highly profitable companies often rely more on retained earnings (a form of equity) and may use less debt because they can fund growth internally.

- Less profitable firms may turn to debt due to limited access to equity markets or to preserve ownership.

- Asset Structure:

- Companies with a significant proportion of tangible assets, such as manufacturing firms, are more likely to use debt because these assets can serve as collateral.

- Businesses with intangible assets, like tech or service firms, may face difficulties securing debt and lean more toward equity financing.

- Taxation:

- Countries with high corporate tax rates make debt more attractive due to the tax shield provided by interest deductions.

- In jurisdictions with lower tax benefits for debt, companies might rely more on equity.

2.2 How to measure a company's capital structure?

A company's capital structure can be measured using two main ratios:

- Debt-to-Equity Ratio (D/E): Measures the proportion of a company's debt relative to its equity, highlighting the balance between borrowed funds and shareholder contributions.

- Debt-to-Capital Ratio (D/V): Represents the proportion of debt in the company’s total capital structure, where capital is the sum of equity (E) and debt (D), also referred to as the firm's value (V).

These ratios provide insights into the financial risk and stability of a company by indicating its reliance on debt to finance its operations.

The extent to which a company uses debt is known as financial leverage or gearing. A higher level of debt indicates a higher degree of financial leverage or gearing.

A secondary measure of the ability of the company to make its interest payment known as the Interest Cover Ratio can sometimes be used to determine the level of debt a company carries is manageable and healthy. It is calculated as:

A high interest cover ratio suggests that the company generates sufficient earnings to comfortably cover its interest payments, indicating a healthy level of debt. Comparing the interest cover ratio to industry standards helps assess whether the company’s debt levels are appropriate relative to peers. For instance, a manufacturing firm with stable earnings may sustain a lower interest cover ratio compared to a technology startup with volatile revenues. Finally, monitoring changes in the interest cover ratio provides insights into a company’s evolving financial health. A declining ratio may signal increasing financial strain, while an improving ratio suggests better debt management.

Learning Objective 3: Capital Structure Theories

Capital structure theories aim to provide a framework for understanding how different capital structures impact shareholder wealth and corporate decision-making. While the optimal capital structure varies depending on a company’s unique characteristics and external environment, these theories offer general principles and insights to guide financial strategy.

Some of the most prominent capital structure theories include:

- Modigliani-Miller Theorem: Proposes that, in a world without taxes or transaction costs, a company’s capital structure is irrelevant to its value. Extensions of this theory introduce the impact of taxes and financial distress.

- Trade-Off Theory: Suggests that companies balance the tax benefits of debt with the costs of financial distress to determine their optimal capital structure.

- Pecking Order Theory: Argues that companies prioritize internal financing, followed by debt, and use equity as a last resort due to information asymmetry between managers and investors.

- Agency Theory: Examines how conflicts of interest between shareholders, managers, and creditors influence capital structure decisions.

3.1 Modigliani-Miller Theorem

The Modigliani-Miller (MM) Theorem, developed by Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller in 1958 [Footnote 1], is a foundational concept in corporate finance. It addresses the impact of a company's capital structure on its overall value and cost of capital. The theorem is based on two main propositions:

- Proposition I (Capital Structure Irrelevance):

In a world without taxes, bankruptcy costs, or market imperfections, the value of a company is independent of its capital structure. This means that whether a company is financed entirely by equity, entirely by debt, or a mix of both, its total value remains unchanged. The reasoning is that the firm's value is determined by its ability to generate cash flows from operations, not by how it is financed. - Proposition II (Cost of Equity and Leverage):

The cost of equity increases with financial leverage because equity holders demand higher returns to compensate for increased risk from using debt. However, the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) remains constant across all levels of leverage.

Note that the MM theorem only hold under key assumptions of perfect capital markets that are characterised as:

- Companies and individuals can borrow at the same interest rate.

- There are no taxes.

- There are no costs associated with the liquidation of a company.

- Companies have fixed investment policies, meaning that investment decisions are not affected by financing decisions.

To illustrate the MM theorem, consider an example.

Imagine two companies, A and B, operating in the same industry and generating identical operating income of $1,000,000 annually. Both companies are valued at $10,000,000, but their capital structures differ:

- Company A: Fully equity-financed, with 1,000,000 shares outstanding, each worth $10.

- Company B: 50% debt-financed, with $5,000,000 in debt (at 5% interest) and 500,000 shares of equity outstanding.

According to MM Proposition I, the value of both companies should remain the same, $10,000,000, regardless of their capital structure. The total value is based on their operating income, not the mix of debt and equity.

For Company B, the cost of equity would increase because equity holders face higher risk due to the financial leverage. If the cost of equity rises to 12% (compared to 10% for Company A), the higher cost offsets the cheaper cost of debt, leaving the WACC unchanged.

In practice, the MM theorem serves as a theoretical baseline, highlighting the conditions under which capital structure would not matter. However, real-world factors such as taxes, bankruptcy costs, and market imperfections do exist, influencing companies' financing choices. For instance:

- Tax Shield Benefit: Debt provides a tax advantage, reducing the effective cost of borrowing.

- Financial Distress Costs: Excessive debt increases the risk of bankruptcy, affecting company value.

The MM theorem offers valuable insights into the fundamental trade-offs in capital structure decisions while acknowledging that real-world complications are critical to practical applications.

3.2 Trade-Off Theory of Capital Structure

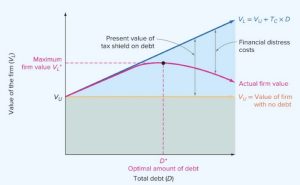

The trade-off theory of capital structure builds on the Modigliani-Miller (MM) theorem by incorporating real-world factors such as taxes and financial distress costs. Unlike the MM theorem, which suggests that capital structure is irrelevant in a perfect market, the trade-off theory acknowledges that firms face a trade-off between the benefits of debt and the costs associated with it. Hence, the optimal capital structure is one that is a balanced trade-off between the benefits and costs of having debt.

The major benefit of debt is the tax shield because interest payments are tax-deductible. This reduces the company’s taxable income and lowers the overall cost of debt, making debt an attractive option.

The major cost of debt is the higher risk of financial distress, a situation where a company's financial obligations cannot be met or met only with difficulty. There are direct and indirect costs of financial distress:

- Direct costs of financial distress or bankruptcy are out of pocket expenses incurred during the bankruptcy process such as legal fees, accounting and auditing fees, administrative costs and consulting fees. These costs can be significant as illustrated in the case of Enron, once a leading US energy company, that filed for bankruptcy in 2011. It is estimated that the total legal and accounting costs exceeded $US1 billion. [Footnote 2]

- Indirect costs of financial distress are the less visible, often longer-term economic consequences that a company faces due to financial instability. These costs arise from the erosion of business value and operational inefficiencies, even before formal bankruptcy proceedings begin. They typically include: loss of customers and revenue, suppliers' stricter supplying agreements, employee turnover and difficulty raising capital leading to lost investment opportunities. While direct costs of financial distress (e.g., legal fees) are measurable, indirect costs often exceed direct costs and have a more profound impact on a firm's long-term value.

The trade-off theory posits that there is an optimal level of debt where the marginal tax shield benefit of debt equals the marginal cost of financial distress. At this point, the firm’s value is maximized, and its Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) is minimized.

This theory can be graphically presented as follows where the optimal amount of debt is determined at the point where the firm value is maximized.

Source: Brealey et al, Principles of Corporate Finance, 14e

The implications of the trade-off theory of capital structure on firms' choice of financing are therefore:

- Profitable Firms Use More Debt: Profitable firms have higher taxable incomes, making the tax shield from debt more valuable. By using debt, they reduce their taxable income, which effectively lowers the cost of financing. For example, utilities companies often have stable and significant profits, which makes the tax benefits of debt attractive. Firms like ExxonMobil or BP are highly profitable and use debt to take advantage of tax deductions while financing large-scale capital projects.

- Firms with Tangible Assets Use More Debt: Tangible assets can be used as collateral, reducing lenders’ risk and the costs associated with financial distress. Companies like real estate investment trusts (REITs) heavily use debt because their assets (e.g., buildings and land) can serve as reliable collateral.

- Volatile and Intangible-Asset-Heavy Firms Use Less Debt: Firms with volatile cash flows or primarily intangible assets (e.g., intellectual property) face higher costs of financial distress and difficulty securing debt. Software firms tend to rely more on equity to finance operations because their assets are largely intangible, and cash flows can be uncertain. Similarly, R&D-focused firms such as biotechnology companies, often in the early stages of profitability, use less debt to avoid financial distress risks.

3.3 Pecking Order Theory of Capital Structure

The pecking order theory of capital structure, proposed by Myers and Majluf (1984) [Footnote 3], is commonly considered an alternative theory to the trade-off theory in explain capital structure. It suggests that firms prioritize their financing choices based on the principle of minimizing costs and asymmetries associated with external financing. It highlights the influence of financing costs and information asymmetry on capital structure decisions, providing a complementary perspective to other theories.

According to this theory, companies prefer:

- Internal Financing: Using retained earnings first, as it involves no transaction costs or information asymmetry.

- Debt Financing: If internal funds are insufficient, firms issue debt, as it is generally less costly than equity and signals less negative information to the market.

- Equity Financing: As a last resort, firms issue new equity, as it is the most expensive and risky due to significant information asymmetry.

Key assumptions underlying the pecking order theory is information asymmetry, a situation where managers have better knowledge of the firm’s value and future prospects than external investors. This creates a preference for financing methods that do not require revealing private information such as debt. This theory also implies that companies aim to minimize costs in choosing their funding methods, hence, they prefer internal funds with no issuance costs followed by debt with moderate costs (interest and financial distress) and equity with high cost (issuance expense and risk of the market undervalue the shares).

The implications of this theory on firms' financing behaviour are therefore:

- Profitable firms reply on retained earnings and avoid external financing while less profitable firms with insufficient internal funds may resort to debt before equity. In practice, some of the most profitable companies in the world such as Microsoft and Apple replied primarily on internal funds and have very minimal borrowings.

- Firms with stable and high internal cash flows tend to have lower leverage, while firms with higher capital needs and lower profits rely more on external financing.

3.4 Agency Theory of Capital Structure

The agency theory of capital structure, developed by Jensen and Meckling (1976),[Footnote 4] explores how conflicts of interest between different stakeholders (e.g., managers, shareholders, and debt holders) influence a firm's financing decisions. It highlights how capital structure can be used to mitigate or exacerbate these conflicts, impacting firm value.

One key agency conflict in a firm, as introduced in Topic 1, is a conflict between managers and shareholders. Managers (agents) may prioritize personal benefits (e.g., job security, perks) over maximizing shareholder value (principals). Therefore, debt can be used as a disciplinary tool in that debt can reduce agency costs by limiting free cash flow available to managers, forcing them to focus on efficient project selection and repayment obligations. For example, high leverage may reduce wasteful spending, as managers are pressured to generate cash to meet debt obligations.

The agency problem can be exacerbated when the company has excess free cash flows, i.e the cash flows in excess of what they need for future investments. When there is excess cash in the company, managers may have a tendency to misuse the cash such as overpay on mergers and acquisitions or accept projects without proper risk analysis. In this situation, debt commitments can constrain free cash flow, aligning managerial actions with shareholder interests. [Footnote 5]

Another key agency conflict within a firm is one between shareholders and debt holders because Shareholders may take actions that benefit them at the expense of debt holders, such as Investing in risky projects to increase potential returns for equity holders, while debt holders bear more risk (asset substitution) or avoiding low-risk projects that benefit debt holders but offer limited returns to shareholders (underinvestment). Higher debt levels increase the likelihood of these conflicts, potentially raising the cost of borrowing or limiting access to debt markets. In addition, debt covenants and collateral requirements are often used to protect debt holders.

When agency conflicts are considered, an optimal capital structure is a trade-off between reducing managerial agency cost by using debt to discipline managers (benefit) and avoiding excessive leverage that could lead to costly debt covenants or financial distress (cost).

Some real-world implications of the agency theory of capital structure are as follows:

- Private equity firms use high leverage to discipline managers of target firms, ensuring cash flows are directed towards debt repayment and operational efficiency.

- Family businesses often prefer lower leverage to retain control and avoid external interference, reflecting an aversion to agency conflicts with creditors/debt holders.

- Companies frequently negotiate covenants to align shareholder and debt holder interests, such as limits on additional borrowing or requirements for maintaining certain financial ratios.

3.5 Key Differences between the theories

The trade-off theory, pecking order theory, and agency theory share a common goal of explaining how firms make financing decisions to maximize value. All three recognize the importance of balancing the benefits and costs of debt and equity, influenced by factors such as profitability, risk, and asset structure. They acknowledge that financing decisions involve trade-offs, whether between tax benefits and financial distress costs, minimizing information asymmetry, or resolving stakeholder conflicts. Additionally, these theories highlight the dynamic nature of capital structure, evolving as firms grow and adapt to new opportunities or risks. Despite their differences, they converge on the idea that no single financing strategy fits all firms.

However, there are key differences between these theories which are summarized in the table below.

| Aspect | Trade-Off Theory | Pecking Order Theory | Agency Theory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Firms balance the tax benefits of debt against the costs of financial distress to determine an optimal capital structure. | Firms prioritize financing sources based on cost and information asymmetry (internal funds → debt → equity). | Capital structure is influenced by conflicts between managers, shareholders, and debt holders. |

| Focus | Optimal debt-to-equity ratio. | Financing hierarchy, not an optimal ratio. | Mitigating agency conflicts to maximize firm value. |

| Tax Shield Emphasis | Strong emphasis on the tax benefits of debt. | Does not explicitly consider tax benefits. | Considers tax indirectly through its role in reducing free cash flow agency costs. |

| Financial Distress Costs | Integral to the theory; firms avoid excessive debt to limit distress costs. | Implies firms avoid debt primarily due to funding preferences, not distress costs. | Considers distress costs as a driver of shareholder-debtholder conflicts. |

| Information Asymmetry | Less emphasis on information asymmetry. | Central to the theory; equity issuance signals potential overvaluation to investors. | Not a central focus but can influence managerial behaviour. |

| Role of Profitability | Profitable firms may use more debt to benefit from the tax shield. | Profitable firms rely on internal funds and have less debt. | Debt disciplines managers regardless of profitability. |

| Debt as a Disciplinary Tool | Not explicitly addressed. | Not a focus. | Debt constrains managerial behaviour by limiting free cash flow. |

| Behavioural Assumptions | Firms actively manage their capital structure to achieve optimal levels. | Firms follow a financing hierarchy passively. | Firms use debt strategically to mitigate agency conflicts. |

| Practical Implications | Encourages firms to find a balance between debt and equity based on benefits and costs. | Suggests firms rely on internal funds first, then debt, and equity as a last resort. | Recommends debt levels that minimize conflicts while aligning stakeholder interests. |

| Examples of Application | Utility companies with stable cash flows maintain higher leverage for tax benefits. | Technology firms often rely on internal funds due to high information asymmetry. | Leveraged buyouts use high debt to align managerial actions with shareholder interests. |

| Key Limitations | Assumes firms can accurately assess the costs and benefits of debt. | Does not explain why some firms maintain stable leverage ratios. | Oversimplifies stakeholder dynamics and may not account for managerial motivations. |

Learning Outcome 4: Estimate the Cost of Capital (WACC)

The cost of capital is the minimum return a company must generate to meet the expectations of its investors—both equity holders and debt holders—given the company’s level of risk. For investors, it represents the required rate of return (RRR) they need to justify their investment in the company.

From the company’s perspective, the cost of capital is what it must provide to investors in the form of interest (for debt) or dividends and capital gains (for equity) to raise funds. If the company’s securities, such as shares and bonds, are actively traded, this cost of capital is observable in the market. The market price of a security reflects the return that investors require based on the company’s risk and the expected cash flows.

To account for the cost of all financing sources, companies calculate and use the weighted average cost of capital (WACC).

From an investor's perspective, WACC represents the weighted average of the required returns on debt and equity, with the weights based on their respective market values. It reflects the return investors expect for providing capital to the company.

From a company's perspective, WACC is the average cost of funds, or the return the company must offer to attract financing from both debt and equity holders. Conceptually, the required returns for investors and the costs incurred by the company are two sides of the same coin.

WACC also serves as the opportunity cost of capital for the company's investors as of today. Companies use this cost of capital as the discount rate (or hurdle rate) to evaluate new investment opportunities with comparable levels of risk. It ensures that investments meet or exceed the minimum returns required to justify their financing costs.

4.1 The WACC framework

The formula for the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) is:

Where:

- E = Market value of equity

- D = Market value of debt

- V = Total market value of the company (E + D)

- re = Cost of equity (required return on equity)

- rd = Cost of debt (required return on debt)

- Tc = Corporate tax rate

A key point to remember is WACC uses the market value of equity and debt, not their book values, to reflect the current cost of capital.

4.2 The cost of equity

The cost of equity is the minimum rate of return required (RRR) by a company’s shareholders, given its riskiness. The cost of equity for a company is a weighted average of the costs of the different types of shares that the company has outstanding at a particular point in time.

There are two alternative methods for estimating the cost of ordinary shares.

Method 1: Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM)

- Estimate the beta of the shares using historical data (for some shares Beta’s are publicly available)

- Determine the current risk-free rate

- Determine the expected market risk premium

- Substitute these values into the CAPM equation re=rf+βx(rm−rf)

There are some practical issues that must be considered when choosing the appropriate risk-free rate, beta, and market risk premium for the above calculation.

- The recommended risk-free rate (Rf) to use is the yield on a long-term Treasury security (eg. 10-year government bonds) because WACC aims to estimate the cost of long-term sources of capital. A long-term risk-free rate better reflects long-term inflation expectations and the cost of getting investors to invest their money for a long period of time.

- Beta (βi) for a share can be estimated using a regression analysis. For most listed shares, their betas are publicly available). Identifying the appropriate beta is much more complicated if the share is not publicly traded. This problem may be overcome by identifying a “comparable” company, with publicly traded shares, that is in the same business and that has a similar amount of debt. When a good comparable company cannot be identified, it is sometimes possible to use an average of the betas for the public companies in the same industry.

- The market risk premium (Rm - Rf) can be estimated using a:

- Historical approach using historical data. For example, historical average difference between the return on a market index (ASX S&P 200) and the risk-free rate (e.g., yield on 10-year Treasury bonds)

- Forward looking approach based on current market prices and expected future cash flows (dividends, earnings).

- The choice of what approach to use depends on data availability, market conditions and analytical preference. A combination of methods can also be used to get a more comprehensive estimate.

Method 2: Constant-growth dividend model

The constant growth dividend discount model (DDM) can be adapted to estimate a company's cost of equity (

) by using the current stock price, expected dividend, and dividend growth rate. The formula is rearranged as:

Where:

- = Cost of equity (required rate of return)

- = Expected dividend in the next period

- = Current price of the stock

- = Constant growth rate of dividend

A key assumption underlying this model is that dividends grow at a constant rate (g) indefinitely. This method is easy to use for firms with stable dividends and is commonly used in industries with consistent dividend policies like utilities. However, it cannot be applied for companies that do not pay dividends nor companies in volatile or high growth industries as their dividend would not be stable.

4.3 The cost of debt

The cost of debt is the effective rate that a company pays on its borrowings, such as loans and bonds. For calculating the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC), the cost of debt is adjusted for the corporate tax rate because interest payments are tax-deductible.

The formula for the after-tax cost of debt is:

Where:

- = Pre-tax cost of debt (required return on debt)

- = Corporate tax rate

Common methods to estimate the cost of debt include:

- Yield to Maturity (YTM) Method: YTM is the internal rate of return (IRR) on the company’s existing bonds, reflecting the market's required return on debt. It reflects the market rate and accounts for time value of money but requires bonds to be actively traded for accurate price data.

- Current Borrowing Rates: Use the interest rate on recently issued debt or loans as a proxy for . This method can be used if the company does not expect significant changes in the cost of borrowing in the future.

- Credit Ratings Approach: The cost of debt can be estimated based on the company’s credit rating (e.g., Moody’s, S&P) and the prevailing interest rates for bonds with similar ratings. It could also be estimated as the risk-free rate plus a premium determined by the company's credit rating. The premium is lower if the company has a better credit rating and vice versa.

- Interest Expense Method: The cost of debt can be estimated based on the interest expenses incurred by the company. This method is simple but based on historical data and hence should be used only when there is no significant changes in the cost of debt in the foreseeable future. The formula to use is

Let's calculate the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) for a hypothetical company based on the following data:

- Risk free rate: 4.38% (based on the yield of the Australian 10-year government bond as of 31 Dec 2024)

- Market risk premium: 6% (commonly used market risk premium in Australia)

- Company's beta: 1.1

- Market Value of equity: $150 billion

- Market Value of debt: $48 billion

- Current yield to maturity: 5%

- Corporate tax rate: 30%

You can follow the steps outlined below to estimate the WACC for the company

1. Calculate the Cost of Equity

Using CAPM

The formula for CAPM is:

2. Calculate the Weight of Equity and Debt

- Equity weight

- Debt weight

3. Adjust the Cost of Debt for Taxes

The after-tax cost of debt is:

4. Apply the WACC Formula

The formula for WACC is:

Summary - Key Concepts in this Topic

1. Characteristics of Debt and Equity: Debt and equity are the primary sources of financing for companies, each with distinct characteristics:

- Debt:

- Fixed obligations, such as interest payments, which are tax-deductible.

- Lower cost compared to equity due to the tax shield but increases financial risk (e.g., bankruptcy risk).

- Examples: Bonds, loans, and credit facilities.

- Equity:

- Represents ownership in the company, with returns in the form of dividends and capital gains.

- No fixed repayment obligation but has a higher cost due to higher risk for investors.

- Examples: Common shares, preferred shares.

A company’s decision to use debt, equity, or a mix impacts its financial health and risk profile.

2. Capital Structure Concept and Measure: Capital structure refers to the proportion of debt and equity used to finance a company’s operations and growth. It can be measured using the following ratios:

- Debt-to-Equity Ratio:

- Debt-to-Capital Ratio:

An optimal capital structure balances the benefits of debt (tax shield) with its risks (financial distress) while minimizing the overall cost of capital.

3. Capital Structure Theory: Several theories explain how firms choose their capital structure:

- Trade-Off Theory: Firms balance the tax benefits of debt against the costs of financial distress to determine the optimal debt-equity mix.

- Pecking Order Theory: Firms prefer internal financing first, then debt, and equity as a last resort, due to information asymmetry and cost differences.

- Agency Theory: Debt can mitigate conflicts between managers and shareholders by limiting free cash flow, but excessive debt may cause conflicts with creditors.

These theories provide frameworks for understanding the trade-offs firms face when structuring their financing.

4. Estimating the Cost of Capital (WACC): The WACC represents the weighted average rate of return required by all investors (debt and equity holders). It is calculated as:

WACC serves as the hurdle rate for evaluating new investments, ensuring returns exceed the cost of financing.

Footnotes

- For more details, see Modigliani, F. & Miller, M. 1958, 'The cost of capital, Corporation Finance and the Theory of Investment', The American Economic Review, 48, pp 261-297.

- For more details, see Bankruptcy Cost – It Could Cost You Much More Than You Expect

- For more details, see Myers, S. & Majluf, N. 1984, 'Corporate Financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have', Journal of Financial Economics, 13, pp 187 - 221.

- For more details, see Jensen, M. & Meckling, W. 1976, 'Theory of the firm: Managerial behaviour, agency costs and ownership structure', Journal of Financial Economics, 3, pp 305-360.

- For more details, see Jensen, M. 1986, 'Agency Cost of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance and Takeovers', The American Economic Review, 76, pp. 323-329.