Topic 7: Fundamentals of Valuation

Introduction

Business valuation is a critical process in corporate finance, providing an objective assessment of a company's value based on its financial performance, market position, and future growth potential. It serves as the foundation for key financial decisions, including mergers and acquisitions (M&A), private placements, venture capital funding, Initial Public Offerings (IPOs), and equity financing. An accurate valuation ensures that companies can raise capital efficiently, negotiate fair deals, and maximize shareholder value.

For instance, as illustrated in the last topic, when a company goes public through an IPO, its valuation determines the initial share price and the amount of capital it can secure. A misvaluation can have significant consequences—if overpriced, investor demand may be weak, leading to post-IPO price declines, as seen in Facebook’s 2012 IPO, where its stock dropped over 50% in the following months. On the other hand, an undervaluation means the company may not raise as much capital as possible, as demonstrated by Alibaba’s 2014 IPO, where the stock surged 38% on the first trading day, indicating strong investor demand.

Beyond IPOs, business valuation plays a crucial role in M&A transactions, where companies must determine the fair price of an acquisition target to avoid overpaying or undervaluing assets. It is also essential in private equity and venture capital funding, where investors need to assess a business’s potential before making an investment.

To accurately determine a business’s value, several valuation methods are used. Each approach has its advantages and limitations depending on the company’s industry, financial structure, and growth stage. Understanding these valuation techniques is essential for executives, investors, and financial analysts to make informed strategic decisions and ensure businesses are fairly priced in the market.

The key learning objectives for this topic include

-

Understand the Nature and Importance of Valuation – Develop a fundamental understanding of valuation, its significance in finance, and its role in investment decisions, corporate strategy, and financial markets.

-

Apply Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Analysis – Learn to estimate intrinsic value by projecting future cash flows, selecting an appropriate discount rate, and conducting sensitivity analysis in corporate finance and investment valuation.

-

Use Comparable Company Analysis (CCA) for Market-Based Valuation – Assess the relative value of a company by identifying suitable peer firms, analyzing financial multiples (e.g., P/E, EV/EBITDA), and applying this method to equity research.

-

Conduct Valuation Using Precedent Transactions Analysis (PTA) – Understand how to determine fair value based on historical acquisition data, deal multiples, and transaction context, particularly in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and private equity.

Learning Objective 1: The Nature and Importance of Valuation

1.1 The Nature of Valuation in Finance

Valuation in finance is the process of estimating the economic worth of an asset, company, security, or investment based on future cash flows, market conditions, and risk factors. It serves as a critical tool for investors, financial analysts, and corporate decision-makers in determining fair pricing for financial instruments, assessing investment opportunities, and facilitating corporate transactions such as mergers, acquisitions, and capital raising.

Valuation is often considered both an art and a science. It involves quantitative techniques such as Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis, which projects future earnings and discounts them to present value, as well as market-based comparisons, such as Comparable Company Analysis (CCA) and Precedent Transactions, which rely on industry benchmarks and historical deal data. However, valuation is also influenced by subjective factors, including market sentiment, economic conditions, and investor expectations, making it a dynamic and context-dependent discipline.

Valuation is used across various domains in finance, including:

-

Investment Analysis – Equity analysts and fund managers use valuation to determine whether a stock is overvalued or undervalued relative to its intrinsic worth, influencing buy and sell decisions.

-

Corporate Finance – Businesses rely on valuation when seeking funding, issuing shares, or considering acquisitions. For instance, a company raising capital must justify its valuation to investors before issuing new shares.

-

Mergers & Acquisitions (M&A) – Companies engaging in M&A transactions must conduct thorough valuations to assess fair deal pricing, negotiate terms, and structure transactions that create shareholder value.

-

Private Equity and Venture Capital – Investors in startups and private businesses use valuation to determine investment size, ownership stakes, and expected returns, often applying methods suited to high-growth companies.

-

Financial Reporting and Compliance – Public companies must report asset valuations under accounting standards such as International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) for accurate financial disclosure.

-

Risk Management and Credit Analysis – Banks and financial institutions assess valuation when issuing loans, ensuring that collateral and business fundamentals support lending decisions.

Given its wide-ranging applications, valuation is an essential component of financial decision-making. It helps investors maximize returns, ensures fair pricing in financial markets, and supports businesses in strategic growth initiatives.

1.2 The importance of financial valuation

Mastering valuation techniques is essential for providing a reliable estimate of asset prices, which serves as the foundation for informed corporate decision-making. Accurate valuation ensures that companies allocate capital efficiently, make strategic investment choices, and mitigate financial risks. Whether assessing the value of a company for an acquisition, determining the fair price of a stock, or evaluating the financial health of a business, a well-executed valuation process enhances transparency, credibility, and financial stability in corporate finance.

To illustrate the importance of valuation, consider the collapse of HIH Insurance's collapse in 2001 - touted as Australia's most significant corporate collapse at that point in time. HIH Insurance, once Australia's second-largest insurance company, went into liquidation with estimated losses of $5.3 billion. A key factor in its downfall was severe mis-valuation of both assets and liabilities, and poor valuation in acquisition. [Footnote 1]

Insurance companies must value their liabilities accurately, ensuring they have sufficient reserves to cover future claims. However, HIH significantly underestimated its insurance liabilities, failing to account for rising claims costs. Instead of using rigorous actuarial valuation models, HIH relied on overly optimistic assumptions about future payouts. This resulted in the company writing high-risk policies—such as workers' compensation and liability insurance—at unsustainably low prices. When claims surged, HIH found itself unable to meet its obligations, leading to insolvency. [Footnote 2]

HIH’s financial statements reflected inflated asset values and understated liabilities, creating a misleading picture of the company’s health. The company failed to mark assets to fair market value, making it appear more solvent than it truly was. This inaccurate valuation misled investors, regulators, and auditors, delaying intervention until the financial damage was irreversible. [Footnote 3]

To add to the financial misjudgement, HIH made several aggressive acquisitions, failing to conduct proper due diligence and valuation assessments. One of the most damaging was the acquisition of FSI Insurance in the U.S., which HIH overpaid for without fully valuing its underlying risks and financial stability. The acquisition turned out to be a major financial drain, as FSI had hidden liabilities that HIH failed to account for, worsening its financial position. [Footnote 4]

The HIH disaster underscores the importance of rigorous valuation techniques in corporate finance. Had HIH properly valued its liabilities, conducted better due diligence in acquisitions, and reported asset values accurately, its collapse could have been prevented. This case serves as a cautionary example of how mis-valuation can lead to catastrophic financial consequences, destroying shareholder value and destabilizing entire industries.

1.3 Key Valuation Methods

To provide a structured approach to valuation, three key valuation methodologies that are widely used across industries will be examined in this topic:

-

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Analysis – This method estimates intrinsic value by projecting a company’s future cash flows and discounting them to present value using an appropriate discount rate. It is widely used in corporate finance and investment analysis, particularly in capital-intensive industries like mining and infrastructure.

-

Comparable Company Analysis (CCA) – This market-based valuation method assesses a company’s value relative to peer firms by using financial multiples such as Price-to-Earnings (P/E) and Enterprise Value-to-EBITDA (EV/EBITDA). This technique is frequently used in equity research and investment banking, especially in evaluating ASX-listed companies.

-

Precedent Transactions Analysis – This approach values a business by analyzing historical acquisition deals in the same industry. It is commonly used in mergers and acquisitions, such as the valuation of Afterpay before its $39 billion acquisition by Block (formerly Square) in 2021, which was one of Australia’s largest fintech deals.

Learning Objective 2: Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Analysis

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis is a fundamental valuation method used to estimate the intrinsic value of an asset, company, or investment based on its expected future cash flows. The core principle behind DCF is that the value of an asset today is equal to the present value of its future cash flows, discounted back at a rate that reflects the risk associated with those cash flows.

Key steps in a DCF analysis therefore are:

- Forecasting future cash flows

- Determining the discount rate

- Discounting and summing the cash flows to obtain the valuation

DCF analysis is widely regarded as the most theoretically sound valuation method because it is based on fundamental finance principles such a time value of money and the risk-return trade-off. Unlike other valuation methods, DCF is not influenced by market noise, investor speculation, or short-term mispricing.

Despite being theoretically sound, DCF has some practical challenges. In relation to valuing a business, this valuation method is highly sensitive to changes in some key inputs such as the discount rate or the growth rate of a business. The discount rate, or WACC, in some cases is difficulty do determine accurately as it depends on market conditions, risk-free rates, and equity risk premiums. For start-ups or companies with unpredictable or negative cash flows, the use of DCF analysis is highly limited.

2.1 DCF Analysis - Bond Valuation

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis is a fundamental method used in bond valuation, as bonds generate predictable future cash flows in the form of periodic interest payments (coupons) and a final repayment of principal at maturity. Since these cash flows occur over time, they must be discounted to present value using an appropriate discount rate, typically the bond’s required rate of return (yield to maturity, YTM).

The steps involved in valuating bonds using DCF analysis are as follows:

Step 1: Identify Bond Cash Flows

A bond provides two types of cash flows:

- Coupon Payments: Periodic interest payments based on the bond’s coupon rate.

- Face Value (Par Value) at Maturity: The principal amount repaid at the end of the bond’s term.

For a fixed-coupon rate bond, the cash flows remain constant, making it well-suited for DCF valuation.

Step 2: Select the Discount Rate

The appropriate discount rate is the required rate of return or the yield to maturity (YTM), which reflects the bond's risk including credit and interest rate risk.

Step 3: Discount Future Cash Flows to Present Value

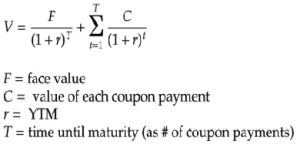

The following formula can be used to calculate the present value of a bond. The first component reflects the present value of the face value while the second component reflects the present value of the coupon payments.

Note that when the bond has a fixed coupon rate throughout its life, the regular coupon payments represent a series of payments at equal time interval of equal value. Hence, the formula for an annuity can be used to estimate the present value of this stream of coupon payments. Of course, the PV function in Excel can also be used to work out the value of bonds efficiently.

2.2 DCF Analysis - Ordinary Share Valuation

Applying a valuation procedure to ordinary shares is more difficult than applying it to bonds for various reasons.

- In contrast to coupon payments on bonds, size and timing of cash flows associating with equity (i.e dividends) are less certain.

- Ordinary shares are true perpetuities in that they have no final maturity date.

- Unlike rate of return, or yield to maturity, on bonds, rate of return on ordinary shares cannot be observed directly.

DCF analysis can still be used to value an ordinary share (equity value) by estimating the present value of future cash flows available to shareholders. This typically involves using either the Dividend Discount Model (DDM) or Free Cash Flow to Equity (FCFE), depending on the company’s financial structure and dividend policy.

The Dividend Discount Model

The Dividend Discount Model (DDM) is a valuation method used to estimate the intrinsic value of a stock based on the present value of its expected future dividends. This model is most appropriate under specific conditions where dividends are a reliable and meaningful measure of a company's financial performance and future cash flows. For example, the DDM is most suitable for companies operating in mature and stable industries and hence have a stable dividend policy.

On the other hand, growth companies that do not pay dividends or pay little dividends tend to be undervalued by DDM. DDM is also not appropriate when dividends are irregular or unpredictable.

DDM accounts for two types of dividend patterns:

- fixed dividends indefinitely (Constant Dividend Model)

- dividends increase at a fixed rate (Gordon Growth Model)

Constant Dividend Model

This model is used for companies that pay a constant dividend indefinitely. For example, many Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) have fixed dividend policies making them idea candidates to be valued using the constant dividend model.

Where:

- P₀ = Present value (intrinsic value of the stock)

- D = Constant annual dividend

- r = Required rate of return (cost of equity)

For example, suppose a company pays a constant annual dividend of $0.40 per share and the required rate of return is 8% pa. The value of the share in this company can be estimated as:

P₀=0.40/0.08=5.00

According to this model the intrinsic value of this share is $5.00.

Gordon Growth Model

This model is used for companies that increase their dividends at a constant rate each year. This model is suitable for stable companies with steady earnings growth.

P₀=D1/(r−g)

Where:

- P₀ = Present value (intrinsic stock price)

- D₁ = Next year’s expected dividend (D₀ × (1 + g))

- r = Required rate of return (cost of equity)

- g = Constant dividend growth rate

Assuming a company just paid a dividend (D₀) of $1.00 per share. The dividend is expected to grow at 5% per year and the required rate of return is 9% per annum.

The Gordon growth model can be applied to provide an estimate of the intrinsic value of the share as:

Step 1: Estimate Next Year's Dividend

Step 2: Apply the DDM Formula

Given these inputs, the value of the company's share is estimated as $26.25 per share.

Free Cash Flows to Equity (FCFE) Approach

The Free Cash Flow to Equity (FCFE) approach is a Discounted Cash Flow (DCF)-based method that values a company's ordinary shares based on the present value of future cash flows available to equity shareholders. Unlike the Dividend Discount Model (DDM), which applies only to dividend-paying companies, FCFE is more flexible and can be used for firms that do not distribute dividends but generate free cash flows that belong to equity holders.

This approach is more sophisticated and involves several steps as outlined below.

Step 1: Calculate Free Cash Flow to Equity (FCFE)

FCFE represents the cash flow available to common shareholders after accounting for:

- Operating expenses and taxes

- Capital expenditures (CapEx) for business growth

- Working capital requirements

- Debt financing (interest and principal payments, new debt issuance)

Where:

- Net Income = Profit after tax available to shareholders.

- Depreciation & Amortization = Added back since they are non-cash expenses.

- Capital Expenditures (CapEx) = Investments in fixed assets (subtracted because they require cash outflow).

- Change in Working Capital (ΔWC) = Adjustments for short-term cash requirements.

- Net Debt Issued = New debt raised minus repayments (added because debt can fund shareholder payouts).

Step 2: Forecast Future FCFE

This step involves forecasting FCFE for a period of time in the future, commonly known as the high growth period. The rationale behind this approach is companies tend to growth strongly for a period time before the growth rate starts to stabilize and decline to a long-term growth rate. The period of high growth therefore depends on:

- the industry that the company is in: a high growth industry means a longer high growth period

- the current growth rate: the higher the current growth rate, the longer the high growth period

- industry barriers to entry: an industry with significant barriers to entry limit the number of newcomers and hence guarantee a longer high growth period for existing companies.

For practical reasons, the high growth period is typically set at 3, 5, 7 or 10 years depending on the above factors.

Step 3: Calculate the Terminal Value

After the high growth period, a terminal value is calculated to account for the value of equity at this point in time. This value captures all FCFE from this point onwards. A common assumption is after the high growth period, FCFE will grow at a lower rate indefinitely (g). Hence, the terminal value can be determined as:

Step 4: Determine the Discount Rate

Since FCFE belongs to equity holders, the appropriate discount rate is the Cost of Equity (Re), calculated using the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) introduced earlier:

Where:

- = Risk-free rate (e.g., Australian government bond yield).

- = Systematic risk measure (stock’s volatility relative to the market)

- = Market risk premium.

Step 5: Discount Future FCFE and Terminal Value to Present Value

Once the FCFE and Terminal Value (TV) are estimated, discount them to present value using the cost of equity:

Where:

- PV(FCFE) = Present value of free cash flows to equity.

- TV = Terminal value

- n = the year when the TV is calculated, also known as the terminal year

Step 6: Calculate the Intrinsic Share Price

PV(FCFE) provides an indication of the value of equity in a company. To derive the intrinsic share price, divide the total equity value by the number of outstanding shares:

The FCFE approach is a powerful alternative to DDM, especially for firms without stable dividend payments. It provides a comprehensive view of a company’s intrinsic value, making it a preferred method for growth companies, tech firms, and firms undergoing expansion.

Free Cash Flow to Firm (FCFF) Approach

The Free Cash Flow to Firm (FCFF) approach is a Discounted Cash Flow (DCF)-based valuation method that estimates the total value of a company (enterprise value) by discounting its future free cash flows before debt payments. Unlike the FCFE method, which values only equity, the FCFF method values the entire firm, which can later be adjusted to determine the equity value per share.

The process to value the entire firm is very similar to the FCFE approach with the following key distinction:

| Aspect | FCFF (Firm Valuation) | FCFE (Equity Valuation) |

|---|---|---|

| What it Values | The entire firm | Equity value |

| Discount Rate Used | WACC (Accounts for both equity and debt) | Cost of Equity (re) (Only considers equity holders) |

| Cash Flow Basis | Free Cash Flow available to both debt and equity holders (do not account for net debt issued) | Free Cash Flow available only to equity holders (account for net debt issued) |

| When to Use | Firms with debt financing (e.g., highly leveraged firms) | Firms with stable capital structure or no debt |

| Final Step | Subtract debt to derive equity value | Directly provides equity valuation |

Learning Objective 3: Comparable Company Analysis (CCA)

Comparable Company Analysis (CCA) is a market-based valuation method that estimates the value of a business by comparing it to publicly traded companies with similar financial and operational characteristics. Instead of relying on intrinsic valuation techniques like DCF, CCA derives a company’s valuation by benchmarking against industry peers based on financial multiples.

CCA is widely used in investment banking, equity research, mergers and acquisitions (M&A), and corporate finance for determining fair market value.

3.1 Key Steps in Conducting CCA

Step 1: Identify Comparable Companies

- Select publicly traded companies with similar industry, size, growth profile, business model, and geographic operations.

- For example, to value Woolworths (WOW.AX), suitable peers might include Coles (COL.AX) and Metcash (MTS.AX) that owns IGA chain of supermarkets.

Step 2: Select Key Financial Multiples

Common valuation multiples used in CCA:

-

Enterprise Value Multiples (Used for Firm Valuation)

- EV/EBITDA – Most widely used, focuses on operating profitability.

- EV/Revenue – Useful when profits are negative.

- EV/EBIT – Excludes capital structure impact.

-

Equity Value Multiples (Used for Share Price Estimation)

- P/E (Price-to-Earnings Ratio) – Common for equity valuation.

- P/B (Price-to-Book Ratio) – Useful for financial institutions.

- P/S (Price-to-Sales Ratio) – Used when earnings are volatile.

Step 3: Calculate Peer Group Multiples

- Compute the selected valuation multiples for each comparable company.

- Determine the mean, median, or range of multiples to establish industry benchmarks.

Step 4: Apply the Multiples to the Target Company

Multiply the target company’s corresponding financial metric (e.g., EBITDA, Net Income) by the selected multiple from peer companies to estimate valuation.

If the industry median EV/EBITDA is 10x and the target company’s EBITDA is $100M, the estimated enterprise value is:

Step 5: Adjust for Market Conditions and Business-Specific Factors

Consider liquidity, growth prospects, risk exposure, and company-specific factors when interpreting results.

For example, if Australia enters a consumer spending slowdown, discretionary retail demand could decline and affect the valuation of supermarkets/retailing companies. In this scenario, investors may apply a discount to retail companies due to lower growth expectations and higher economic uncertainty. A 10% discount can be applied to account for weaker market conditions.

Sometimes, business-specific adjustments are required. As an example, when the company has a larger market share, better supply chain efficiency and higher profit margins than its peers, a valuation premium may be justified.

3.2. Pros and Cons of CCA Analysis

Just like other valuation methods, CCA has a few strengths and weaknesses.

Pros of CCA Analysis

- Market-Based and Real-World Pricing – Uses current market prices, reflecting real investor sentiment.

- Quick and Simple to Apply – Easier and faster than DCF, making it ideal for rapid valuations.

- Useful for Benchmarking – Helps compare financial performance and valuation against industry peers.

- Commonly Used in Investment Banking and M&A – Provides a practical reference for pricing deals and IPOs.

- Flexible in Application – Can be applied across different industries and company sizes.

Cons of CCA Analysis

- Dependent on Market Conditions – Stock market fluctuations and investor sentiment can distort valuation.

- Difficult to Find Truly Comparable Companies – Even in the same industry, firms may differ in size, business model, and profitability.

- Ignores Company-Specific Intrinsic Value – Does not consider unique competitive advantages or long-term potential although this issue can be partly alleviated by conducting a firm-specific adjustment to valuation.

- Accounting Differences May Distort Multiples – Differences in financial reporting practices can make direct comparisons inaccurate.

- May Not Work for Private or High-Growth Firms – Hard to apply when there are no public comparables or when companies have volatile earnings.

Given the above characteristics of CCA, it's ideal to value publicly listed companies as well as to establish industry benchmarking. It is also useful when DCF is impractical due to unpredictable future cash flows for companies like start-ups.

Learning Objective 4: Precedent Transactions Analysis (PTA)

Precedent Transaction Analysis (PTA) is a market-based valuation method that determines the value of a company based on the pricing of similar past mergers and acquisitions (M&A) transactions. This approach assumes that historical acquisition prices provide a fair benchmark for valuing a similar company today.

Investment bankers, corporate finance professionals, and M&A analysts use PTA to assess the fair acquisition price for a company by examining comparable deals where similar businesses were bought or merged.

The following process illustrates how the PTA is applied in practice.

Step 1: Identify Relevant Precedent Transactions

- Look for past M&A deals in the same industry, with similar business models, financial profiles, and geographic presence.

- Consider transactions that occurred recently, as market conditions change over time.

- Example: If valuing an Australian retail company, past acquisitions of Coles (COL.AX) or Metcash (MTS.AX) would be relevant.

Step 2: Gather Transaction Details

- Collect data from public filings, company announcements, investor presentations, and databases such as Bloomberg and Capital IQ.

- Key transaction details include:

- Purchase Price (Transaction Value)

- Type of Buyer (Strategic vs. Financial - Private Equity vs. Corporate)

- Premium Paid (Offer Price vs. Pre-Deal Market Price of Target)

Step 3: Calculate Key Valuation Multiples

From the transaction data, extract valuation multiples used to compare deals, such as:

-

Enterprise Value Multiples (For Full Firm Valuation)

- EV/EBITDA – Most commonly used for profitability comparisons.

- EV/Revenue – Useful for companies with negative earnings.

-

Equity Value Multiples (For Shareholder-Level Valuation)

- Price-to-Earnings (P/E) Ratio – Common for equity valuation.

- Price-to-Book (P/B) Ratio – Used for financial firms.

Assuming BHP acquired a mining firm for $5B, and the target company’s EBITDA was $500M, the EV/EBITDA multiple is:

Step 4: Apply the Multiples to the Target Company

Use the median or range of transaction multiples to estimate the value of the company being analyzed.

For example, if past transactions in the retail industry had a median EV/EBITDA of 9x and the target company’s EBITDA is $600M, the estimated enterprise value is:

Step 5: Adjust for Market Conditions and Business-Specific Factors

Consider differences between the precedent transactions and the target company and adjust for economic trends, company growth, profitability, or synergies. For example, if the market is currently weak, apply a discount to reflect lower deal-making activity.

The key difference between CCA and PTA is that CCA relies on current market data from publicly listed companies to value a company with similar characteristics while PTA used historical M&A transaction data which often include a premium that the acquiring company usually offers the target to make their bid attractive. PTA is therefore more relevant in valuing companies for M&A and buyout purposes.

Summary - Key Concepts in this Topic

1. The Nature and Importance of Valuation in Finance

- Valuation is the process of determining the worth of an asset, company, or investment using financial models and market-based approaches. It is critical for investment decisions, mergers and acquisitions (M&A), corporate finance, and financial reporting.

- Methods of valuation include Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis, Comparable Company Analysis (CCA), and Precedent Transaction Analysis (PTA).

2. Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Analysis

- DCF analysis is an intrinsic valuation method that estimates the present value of expected future cash flows. It is based on the time value of money (TVM) principle where future cash flows are discounted back to the presence to reflect their value today. It can be applied to value any financing asset include debt and equity.

- Two common valuation approaches:

- Free Cash Flow to Firm (FCFF) – Values the entire company.

- Free Cash Flow to Equity (FCFE) – Values only equity holders' cash flows.

3. Comparable Company Analysis (CCA)

- A market-based valuation method that values a business by comparing it to similar publicly traded companies using financial multiples.

- This valuation method is easy to apply and reflects current market pricing, but it can be challenging to identify a perfect comparable company.

4. Precedent Transaction Analysis (PTA)

- A market-driven valuation approach that uses past M&A deal prices to estimate a company's worth.

- This method reflects market transaction values which include any premium that is offered to the target company. It's typically used to value companies for M&A and buyout purposes.

Footnotes

- For more details, see Why this was Australia’s most significant corporate collapse

- For more details, see Why insurers fail by PACICC

- For more details, see The failure of HIH Insurance by the HIH Royal Commission

- For more details, see FAI takeover precipitated HIH collapse