3 Establishing Your Purpose and Career Identity

To be yourself in a world that is constantly trying to make you something else is the greatest accomplishment

Ralph Waldo Emerson, American poet

Learning Objectives

Learning Objectives

On completion of this chapter you should be able to:

- Understand what professional purpose is and how this aids your career development.

- Reflect on your underlying values and aspirations and how these can be used to help define your career identity.

- Appraise the concept of career identity and reflect on how this translates to your own circumstances.

- Translate the theoretical knowledge provided into a set of strategies for improving your employability on graduation.

Introduction

For young people, self-perceived employability refers to ‘the perceived ability to attain sustainable employment appropriate to one’s qualification level’ (Rothwell et al., 2008, p. 2). To help students develop their employability, vocational and higher education institutions (V&HEI) have historically had a skills-based focus of employability as described in Chapter 2, but this has declined in more recent years as consensus emerges that employability provision needs to be multi-dimensional, experiential, and embedded in the curriculum (Artiss, 2019). In practice, learning to become employable entails undertaking multiple activities both within the educational setting such as work-integrated learning, and outside it, through for example part-time work and/or voluntary work. Employability practices in educational settings need to start with the formation of a professional purpose and the building of a career identity.

Professional Purpose

Professional purpose reflects an individual’s level of commitment to developing a professional future aligned to their personal values, aspirations, and outlook. It has been argued that the rapid rate of change in the workplace means that skills learning is not a sufficient strategy on its own to raise employability. The new work environment requires the development of a growth mindset (we’ll look at this in more depth in Chapter 7) and a deep understanding of an individuals own worldview, beliefs, and values (Bates et al., 2019).

Watch our industry expert, Sean Tierney, discuss value alignment, identity and job changes.

Watch our industry expert, Sean Tierney, discuss value alignment, identity and job changes.

Values represent basic convictions that an end-state is preferable to an opposing end-state. They contain a judgemental element that is related to an individual’s ideas of right, wrong, good, and bad; they have both content and intensity attributes. The content attribute says that the end-state is important, and the intensity attribute specifies how important is it. So, if you think about a work example, the content attribute of autonomy in your job might be important but it might not be very intense, meaning that if other things that you evaluate as desirable are good e.g. a high salary, you may be willing to have less autonomy in your work. However, if your content attribute of ethical practice is very intense, then you might not work for a defence firm, no matter how much salary they offered. All of us have a hierarchy of values that form our value system, and values, once developed, are fairly stable and enduring over time. A more likely scenario is that you might enter a workplace that you believe treats people equitably but then find out that this is not so and that favouritism leads to promotions for example, rather than being based on merit. This inequitable behaviour would go against your values system, meaning you’ll be disappointed and become disaffected. This may lead to being less productive at work and ultimately leaving the organisation having not had a very good experience.

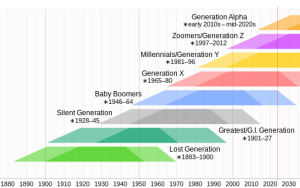

A professional purpose mindset commits someone to develop a professional future aligned with their own values and aspirations. For V&HEI students, therefore, time spent developing an understanding of your values, beliefs, and aspirations through reflection and practice, often but not necessarily aligned to your studies, will lead you to develop your professional purpose. This in turn leads to the construction of a career identity, which can be re-constructed over time. It is interesting that some research suggests that different age cohorts have different values (Table 3.1). Figure 3.1 shows the various generational cohorts and this is important to understand as current workplaces will often have four different age cohorts working together, potentially even five; Table 3.1 shows the four common age groups working together and their dominant work values.

Figure 3.1 ‘Generation timeline’ Cmglee, 2023. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Table 3.1 Dominant work values in today’s workforce (adapted from Valantine, 2021)

| Cohort | Age in 2019 | Dominant work values |

| Baby Boomers | 55-73 | Success, achievement, ambition, loyalty to career |

| Gen X | 39-54 | Work/life balance, team-orientated, dislike of rules, loyalty to realtionships |

| Millenials | 23-38 | Confident, career focused, financial success, self-reliant, work flexibility, upward mobility, feedback |

| Gen Z | 7-22 | High aspirations, social responsibility, interesting and meaningful work, autonomy |

Career Identity

Career identity can be described as a way in which individuals consciously link their own interests, motivation and competencies with acceptable career roles. Career identity has been reported to be an important indicator for both general well-being and career development and satisfaction (Praskova et al., 2015; Stringer and Kerpelman, 2010). Career identity develops through active career preparation activities such as planning, exploration, decision-making and work experience. Individuals need to make sense of their experiences, become aware of their likes and dislikes and commit to career choices. This active reflection leads to the construction and re-construction of an individual’s career identity and clarity of career path.

Research has shown that career identity is the foundation of an individual’s perception of one’s employability, and it is linked to better reasoning about future career opportunities, less career self-doubt, and future occupational attainment (Praskova et al., 2015). Therefore, if you are a current student or a recent graduate, spending some time reflecting on your career purpose and identity is time well spent so complete Exercise 3.1 now.

Exercise 3.1

Exercise 3.1

Set aside some time to reflect about your values, ask yourself:

- What are you passionate about?

- What wouldn’t you give up for a job or career?

- Imagine yourself in 20 year’s time – what makes you happy? What are you doing if everything works out perfectly?

Then, take the Claremont Purpose Scale quiz to see how well your current activities meet your purpose.

Clarify your values by:

- Writing down your most important priorities.

- Discussing with your family and friends – this can help you clarify what’s important.

Developing your career identity

There is evidence that university students who commit to career-related exploration during their studies are best able to adopt career self-management behaviours that enhance their employability after graduation (Artiss, 2019; Bates, 2019). Strauss, Griffen and Parker (2012) found that the more an individual holds a clear view of their future self at work, the more this will motivate proactive behaviour. Therefore, V&HEIs need to provide students with time to identify a view of their future work self, time to test out the identity, and to re-evaluate and re-test it. This means that V&HEI should not leave graduate employability interventions towards the end of students’ study time, but introduce these concepts from first year (Mullen et al., 2019).

Figure 3.2 ‘A career identity learning cycle’ © Michelle Gander, 2023. CC BY-NC 4.0.

Artiss (2019) showed that provision of early career interventions promoted a sense of clarity about career intentions which in turn led to better satisfaction with work after graduation. This points to the need for students to have time to work through a number of iterations to identify and test the formation of their career identity. Using Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning cycle, which is defined as ‘the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience’ (p. 41), Gander’s (2023) career identity learning cycle (Fig 2.1) allows for individuals to learn through four different modes involving action/reflection and experience/abstraction: experiencing, reflecting, thinking, and acting. The more time that students are provided with to go through this cycle multiple times, the stronger career identity that will be created.

Exploring Careers

If then, we need to go through cycles as highlighted in Fig. 2.1 to explore, test and reflect on what is important for us in our careers, how can we start this process? You’ve already started to explore your values in Exercise 2.1 so you should have some idea of what is important, and what you wouldn’t give up. Career values have been found to be a critical aspect of an individual’s motivations and takes centre stage in multiple career theories (Table 3.2) such as Theory of Work Adjustment (TWA, Dawis, 2001), Career Anchors (Schein, 1996), the Protean Career (Hall, 1976), and the Boundaryless Career (Arthur, 1994).

Table 3.2 Key career values in various contemporary career theories

| TWA core values | Career anchors | Protean career | Boundaryless career |

| Achievement | Technical competence | Professional commitment | Skills utilisation |

| Comfort | Lifestyle | Work-life balance | Work-life balance |

| Status | Managerial competence | Personal development | Career development |

| Altruism | Service/dedication to a cause | Meaningful work | Meaningful work |

| Safety | Security/independence | ||

| Autonomy | Autonomy/independence | ||

| Pure challenge | Learning/growth | Skill development |

Table 3.2 shows that although there is some difference in the values between the different career theories, many are similar and cut across all career theories mentioned. We can therefore infer that these values are critical to career satisfaction and if our values do not align with our careers, dis-satisfaction occurs which can lead to stress, burnout and depression which has been evidenced in multiple occupations including nurses and other health professionals, medics, teachers, blue collar and white collar workers (Tennant, 2001). As early Gen Zs (born 1997–2012) start to hit the workplace, research has shown that this cohort prioritise meaningful work (Schroth, 2019). It has been reported that a growing number of young people are taking into account the climate commitments of the companies they work for. A recent KPMG survey showed that 20% of recent graduates and office staff had turned down job offers due to a company’s environment, social and governance (ESG) factors, the percentage was higher for those aged 18-24 (McCalla-Leacy, 2023). This is one factor that is pushing companies to commit to embed such values into their organisational culture as part of their triple bottom line. For example, some large and well-known companies are committing to becoming net zero, such as Unilever, Salesforce, L’Oréal, Microsoft and Nike. Deloitte (2022) also suggest that there will be a new classification of worker. Where the industrial revolution gave rise to blue collar workers, and professionlisation to white collar workers, green collar workers will be about how decarbonisation influences their work and skills. To understand what a values-based, or meaningful career might look like for you, do Exercise 3.2 now.

Exercise 3.2

Exercise 3.2

Set aside some time to reflect about what meaningful work means for you – work that is satisfying, meets your values and potentially contributes to solving a problem or problems you are passionate about.

To help you, you can go to www.80000hours.org. This website has been created using the results of 10 year’s worth of research to help you figure out how you can use your career for good. You have 80,000 hours in your career – use those hours to do good!

Researching your career

One of main predictors of career success are the relatively broad and stable Big 5 personality traits: extraversion (also often spelled extroversion), agreeableness, openness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism (Heslin, Keating and Minbashian, 2018). Personality plays an important role in career success because organisational life allows for stable traits to manifest in people’s behaviour at work. This leads to the ability for personality traits to be accurately assessed and aligned to varying careers. You may already have a strong indication of the career you want to pursue, in which case you can skip this section, or do the career test below just for interest. However, if like many students you do not really know the career you want to pursue, then the first place to start thinking about your career is to take a personality-based career assessment; go to Exercise 3.3 now and take the test.

Exercise 3.3

Exercise 3.3

Many people need help in establishing what sort of careers are out there and what they have interest in and the personality for.

If you need help in exploring your fit with different careers, you could take the free online career assessment by Truity. Look for career test under the personality tests banner.

Other tests are available, for free and for a fee. You may also have access to career assessments via your local V&HEI Careers Service.

Once you have some idea of a career or careers you want to find more about, then you can start researching these. You can do this easily online and by using your networks. For example, I took the test and, surprise, surprise one of the careers that best matched my personality was college professor! I then went online and Googled ‘how to become a college professor’ and got 614,000,000 results. The top one was from a major online recruiter (Seek.com), which provided a list of tasks this job undertakes. There were many more sites that I could have explored.

If I was now convinced that I wanted to follow this path, I could then start to use my real-world networks to see if I could find a college professor to talk to. The idea of six degrees of separation often holds true, so even if you do not know a college professor personally, then someone not too many steps away from you in your social network will – try to find this link. Once you have a contact, do not be afraid to reach out, most people will be generous with their time and talk to you. It would be best to go to that meeting with a few questions, so that you can prompt the person to answer the questions you really want answers to. If we stick with the college professor example, you could potentially ask questions such as: what does a typical day consist of? How much teaching will I do compared to how much research? Is it easy to get promoted? What is it like to work in a university? And so on.

Career development opportunities

There are various ways to enhance your employability whilst you are studying. Many students already have part-time work, and this can be an excellent way of gaining several work-related skills, even if it’s not work that you will want to continue when you graduate. For example, if you are a barista, you are gaining skills in customer service, time management, and staying calm under pressure – all soft skills (we will discuss these further in Chapter 7) that translate into any other type of work. Of course, ideally you could gain work experience in the career you think you want or work adjacent to that career. If you are studying to be an accountant, you can get work as a junior bookkeeper, if you are studying a creative arts course you could work as a theatre officer and so on. If getting paid part-time work in an area that you’re interested in finding out more about is difficult, you could undertake some voluntary work. A caveat here, I know that for many students being able to do voluntary work is a luxury, and if you need paid employment then this should always take precedence, however, if you find time for voluntary work, and it is certainly relatively easy as many institutions will gratefully take on volunteers especially in the charitable sectors, this will prove an advantage when you come to apply for your graduate job.

Within your course, especially at university, you will have the option of undertaking a work-integrated learning (WIL) experience. Many courses now have integral WIL components as core, but, even if one is not core, there should be a unit of study available to you that you can take as an elective. WIL has been shown to improve a student’s self-efficacy and Martin and Rees (2019) showed that undertaking a WIL experience added value to students generally by, improving their self-efficacy, having an enjoyable experience, reaffirming their employment pathway, and providing a point of difference on their CVs.

In Summary

This chapter has explored how V&HEI have started to move beyond a training focussed approach to employability as a process approach and started to embed career activities within curriculum to help students find their professional purpose and career identity. We learnt that spending some time thinking about your professional purpose, your personality, and your career identity gives you a solid foundation to go and explore actual jobs to understand the requirements needed to be successful. It is now time to move on to some practical activities you can do to enhance your employability.

Exercise 3.4

Exercise 3.4

Think about the following questions and prompts:

- Reflecting on the outcome of the above exercises, do you now have a picture of your underlying values, aspirations and nascent career identity?

- Can you now start to explore some specific job roles to gain a better understanding of the requirements?

- Can you now develop a set of goals related to the above and a plan on how to meet them?

Key Takeaways

Key Takeaways

- Find your professional purpose by reflecting on your values and what motivates you.

- Explore how your personality aligns with different careers to ensure the maximum likelihood of career success.

- Use social media and real-world networks to find our more about a career you’re interested in.

- Use part-time and voluntary work to gain work experience.

- Undertake a work-integrated learning / placement activity whilst you’re studying.

References

- Arthur, M. B. (1994). The boundaryless career: a new perspective for organizational inquiry. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(4), 295–306. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030150402.

- Artiss, J. (2019). Learning to be employable. In: Graduate Careers in Context: Research, Policy and Practice, Eds. C. Burke and F. Christie. Taylor Francis.

- Bates, G. W., Rixon, A., Carbone, A. and Pilgrim, C. (2019). Beyond employability skills: developing professional purpose. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 10(10), 7–26.

- Dawis, R. V. (2001). Towards a psychology of values. The Counseling Psychologist, 29(3), 458–465. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000003031003008.

- Deloitte. 20220. Work towards net zero: the rise of the green collar workforce in a just transition. Deloitte Global. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/gx-deloitte-work-toward-net-zero-Nov22.pdf.

- Hall, D. T. (1976). Careers in Organizations. Goodyear.

- Heslin, P. A., Keating, L. A. and Minbashian, A. (2019). How situational cues and mindset dynamics shape personality effects on career outcomes. Journal of Management, 45(5), 2101–2131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318755302.

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Prentice Hall.

- Martin, A. J. and Rees, M. (2019). Student insights: the added value of work-integrated learning. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 20(2), 189–199.

- McCall-Leacy, J. (2023). Climate quitting – younger workers voting with their feet on employer’s ESG commitments. KPMG. https://kpmg.com/uk/en/home/media/press-releases/2023/01/climate-quitting-younger-workers-voting-esg.html.

- Mullen, E., Bridges, S., Eccles, S., Dippold, D. (2019). Precursors to employability—how first year undergraduate students plan and strategize to become employable graduates. In: Employability via Higher Education: Sustainability as Scholarship, Ed. A. Diver. Springer.

- Praskova, A., Creed, P. A. and Hood, M. (2015). Career identity and the complex mediating relationships between career preparatory actions and career progress markers. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 87, 145–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.01.001.

- Rothwell, A., Herbert, I. and Rothwell, F. (2008). Self-perceived employability: construction and initial variance validation of a scale for university students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73, 112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.12.001.

- Strauss, K., Griffin, M. A. and Parker, S. K. (2012). Future work selves: how salient hoped-for identities motivate proactive career behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(3), 580–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026423.

- Schein, E. H. (1996). Career anchors revisited: implications for career development in the 21st Century. The Academy of Management Executive, 10(4), 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0974173920070407.

- Schroth, H. (2019). Are you ready for Gen Z in the workplace? California Management Review, 61(3), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125619841006.

- Stringer, K. J. and Kerpelman, J. L. (2010). Career identity development in college students: decision making, parental support, and work experience. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 10(3): 181–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2010.496102.

- Tennant, C. (2001). Work-related stress and depressive disorders. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 51(5): 697–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00255-0.

- Valantine, A. C. (2021). Baby Boomers, Generation ‘X’ and Generation ‘Y’ in the workplace: a melting pot of expertise. Resource 1, 16 August 2021. https://www.resource1.com/baby-boomers-generation-x-and-generation-y-in-the-workplace-a-melting-pot-of-expertise.

Professional purpose can be defined as the ‘driver of the development and pursuit of career-related goals related to a general career identity’ (Bates et al., 2019).

Where companies commit to focusing on social and environmental concerns

Self-efficacy can be defined as the beliefs in your own capability to organise and implement the courses of action required to attain your goals.