Chapter 3: Discovering yourself as a learner

Liam Frost-Camilleri

Learning Objectives

- Recognising and reflecting on your learning strengths and areas of improvement

- Challenging fixed perceptions of ability and growth

- Managing learning strategies to apply practical solutions to manage tasks, yourself, and relationships

- Embracing productive struggle as a means to grow and adapt

3.1 Who are you as a learner?

Most of the research published concerning getting to know who you are as a learner is focused on how educational institutions support students (or, how they do not). Some research highlights the importance of an accessible learning environment for students (Closs et al., 2021), while others explore the link between creating a sense of belonging and helping students remain engaged (Waite et al., 2023). While institutes such as universities have a responsibility to cater to your engagement and learning needs, the challenge that every student faces when attending university is discovering and understanding themselves as a learner. This understanding can then be leveraged to make your time in higher education more enjoyable and successful.

This question of ‘who are you as a learner?’ is more complex than most people tend to realise. Due to some poor practices with theory, most students will call themselves ‘visual learners’ or ‘hands-on’ learners, when there is no empirical evidence to support the concept of learning styles at all (Frost-Camilleri, 2021). In fact, some researchers criticise the learning styles idea because it makes learning appear too simplistic (Nancekivell et al., 2020). When not referring to learning styles, many students tend to think about their learning in terms of what they are good at and what they feel they struggle with. These students will say things like: “I’ve always been a good reader” or “I’ve never been good at maths”, but these statements are quite finite or fixed and can make it difficult to challenge, change, and grow your understanding and skill. In many ways, the most important thing about becoming someone who is aware of who they are as a learner is to adopt a less fixed perspective.

Many students equate a strength with something that they enjoy, but enjoyment does not always equal strength. One of the best ways to determine a strength is when it is highlighted by others. It is worth reflecting on the advice and praise you have received about the things that you have done well. A similar point can be made for areas of improvement as your teachers, friends, and family can indicate where improvement is needed. Accepting the perspectives of others can be emotionally confronting, but it is an important aspect of academic growth.

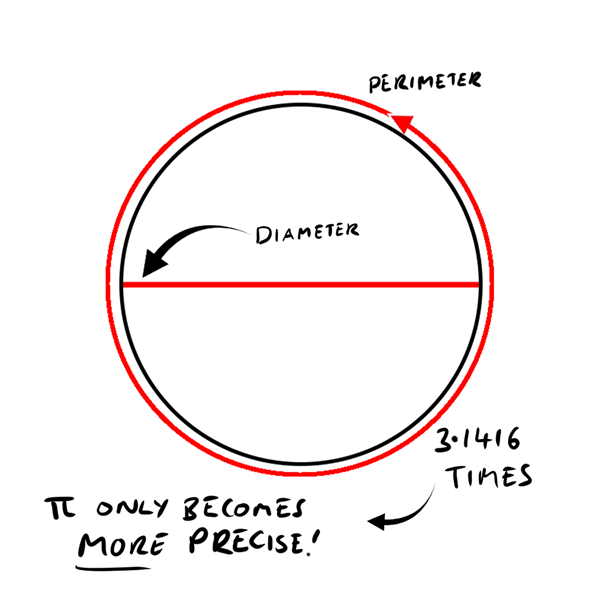

The truth is, however, that every aspect of yourself as a learner can be developed, no matter how brilliant or horrible you are at something. An excellent writer can still refine their writing in the same way that a person who has difficulty understanding mathematical concepts can develop their knowledge. A good metaphor for this concept is the mathematical symbol pi (π). See figure 3.

To find π you need to know the diameter of a circle. The diameter is a straight line that runs through the centre of a circle. If you take the diameter and wrap it around the perimeter (the line running along the outside) of the circle, it will wrap around 3.1416 times. The important part of π is that the number never ends and does not have a pattern. If you tried to remember every digit after the decimal, you would never finish remembering numbers.

π never ends; it just becomes more accurate. Thinking of your skills as a never-ending patternless list of numbers is a good way to remember that no matter how precise or ‘good’ you think your skills are, they can always be developed to become more precise, just like π. This also means that there is no such thing as doing something ‘perfectly’; there is only how far you have come on your learning journey, or rather, how far you would like to go on your journey.

Moving your thinking from the fixed idea that you simply have unmovable strengths and weaknesses, or that you are a particular kind of learner is a difficult shift to make for many students. Looking to understand concepts straight away, or attaining a High Distinction on your first try are rare achievements. Additionally, many students will see skill development as ‘fixing’ the parts of themselves that are not ‘good enough’. We are not ‘fixing’ ourselves, because nothing is broken. Clearly, if you are enrolled, then you are good enough to do the course. Getting to know who you are as a learner helps you to be more self-compassionate while you make small improvements. Knowing yourself also means you can better understand the individual work you need to do to achieve your goals.

3.2 Being honest with yourself

Keeping your learning journey in mind while you try to identify your areas of strengths and/or improvement can be difficult, as many students are trained to think of their skills as finite and fixed. If you received a series of reports that highlighted how much you struggled with mathematics over the years for example, it can be very difficult to feel like you can improve these skills. However, being honest with yourself is extremely important for your growth.

One effective way of getting to know yourself is to have conversations with the people who know you. Talking to your friends, partner, mentors, colleagues, other students, teachers, and parents while listening intently can be confronting and may make you question your identity as it challenges the story you have been telling yourself. It is, therefore, very important that you go gently into this area of getting to know yourself through the eyes of others while keeping an open mind.

To keep your conversations on track in terms of growth, try to use more neutral or positive language when discussing yourself with the people who know you. Instead of asking ‘what am I bad at?’ ask, ‘what areas could I improve upon?’. Additionally, ask some follow up questions that relate to how these skills can be improved. A question like, ‘how do you think I could get better at…?’ could help you with some strategies to develop your skills. Similarly, when discussing your strengths, ask what you do that makes it a strength. For instance, if someone tells you that you are an effective writer, you can follow up with, ‘what about my writing makes me effective?’.

For some people, answering questions like this can be difficult, so it would be best not to force the issue. Viewing this task as merely an exercise to see what you might focus on next might not require an intense interrogation, but the conversations can be quite interesting and freeing as you learn more about yourself as a learner.

3.3 Taking stock of your skills

Taking stock of your learner skillset as it relates to university is an important step toward getting to know yourself. We tend to break this task into three categories: forging positive relationships, task management, and self-management.

Positive relationships are important as they give you a chance to discuss your ideas and develop your understanding of course or unit content. At university you will encounter people from diverse backgrounds and cultures, making the ability to build a quick and lasting rapport very useful. Try to forge these relationships by asking your peers questions and listening intently to their responses. Get to know your peers and try to remember that every person in your class is a resource that can help you to further develop your understanding. Group work is also an important part of attending university, which means skills in negotiation, discussion, and working with others will be especially helpful (negotiating group work is covered in more detail in Chapter 8).

The ability to manage tasks is an extremely important aspect of being successful at university. As you will have no doubt noticed by now, lecturers and tutors will not spend much time motivating you to complete weekly readings or any other tasks, leaving you in charge of getting all you can out of your university experience. Consider your usual habits when completing tasks: Do you know how to research? Do you usually understand what assessment tasks are asking you to do? Do you know how to move between different online platforms and navigate different websites? Can you navigate assessment criteria to determine how best to approach a task? Answering questions such as these is crucial for determining your skill level. By evaluating your strengths and identifying areas where you may need support, you can better plan and manage the process of successfully completing university tasks. It is also important to recognise that different tasks require different skills, so be sure to focus on the specific skills needed for each task to ensure success.

Being able to manage yourself requires a better understanding of who you are and your relative strengths. Think about the process you tend to undertake when completing tasks. Some students will need a dedicated workspace that needs to be quiet and distraction-free. Others will need music and noise to keep their motivation going. Some students need to procrastinate to ‘think’ about the tasks they are completing, while others block out dedicated time in their calendar or they will simply not find the time. It is worth reflecting on what helps and what hinders you when you are thinking about working on your university tasks.

Working on developing positive relationships, how you manage tasks, and how you manage yourself are effective ways of ensuring you are maintaining a positive mindset of improvement. Try to experiment with ways that you can improve in these areas and stay curious while you do.

Rate the following questions from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) to help you reflect on your strengths and areas of improvement. Be sure to be honest in your responses and create an action plan on how you can improve yourself further.

- I feel confident in my ability to grasp new concepts quickly.

- I receive positive feedback from others on my work regularly.

- I tend to understand the feedback that I receive.

- I can easily explain complex ideas to others.

- I can remain focused on my studies.

- I am often motivated to study.

- I can organise my time effectively.

- I can organise my space to help me study better.

- I use a variety of study methods when studying.

- I often participate in classes.

- I ask clarifying questions in class when I am not sure of something.

- I feel confident talking in front of the class.

- I know how to navigate group work tasks.

- I know how to set time aside to complete required tasks.

- I approach revision and preparation for tasks in a structured manner.

- I set clear goals for improving my strategies.

- I actively seek out and use support resources.

- I regularly review and adjust my study plans based on my progress.

- I have a clear action plan for addressing my areas of improvement.

- I find reading and analysing text easy.

- I find writing and explaining my thoughts easy.

3.4 Getting close to the course content

Some of what has been covered in this chapter can be quite overwhelming. Feeling worried or anxious about the process (further addressed in Chapter 9), is completely normal, especially if it is the first time you have studied at university and you want to be successful. However, there are some practical ways that you can develop your skills to help you better engage with your course or unit and alleviate some of this anxiety. Preparing before class, participating in the class, and immersing yourself in the course or unit are three strategies that are quite effective. Just remember to leverage the strengths that you have acknowledged above when implementing these strategies.

Your goal should be staying active and making the most of your class time. Aim to always ask clarifying questions when you do not understand something (unless, of course, it is in a lecture and there is no opportunity to ask questions; in this case, write the question down so you can ask it during the tutorial, or write it on an online discussion board forum). You may be a student who is already comfortable with talking in front of a class, but if you are not, it is important to become comfortable with this. Remember that higher education is not like secondary school. University classes, whether on campus or online are much less worried about the social pecking order and much more interested in understanding and growth. Engage in discussions, question your beliefs and values, and seek clarification from your lecturer on anything you are unsure about. The more you interact, the richer your university experience will be. It is also important to focus on the weekly activities and readings set by your lecturers. By looking into these tasks you will find it much easier to engage in class content and develop your self-efficacy.

Immersing yourself in the course or unit means exploring everything it has to offer, including the assessments, readings, topics, and general concepts. Getting to know the course can be as simple as reading any material that discusses the assessments and the content. While reading, get into the habit of recording any questions that you might have, so you are ready to discuss them in class. Making a list of relevant vocabulary used in the course with definitions might also be helpful in successfully navigating the content. This is called a ‘glossary of terms’ and will help you to develop your academic language. Immersing yourself can also involve getting to know the finer details of the course, like the thinkers who first discussed the theories that you are examining. Ask yourself if you know who this person is/was, what their areas of interest were/are? Why did they make the contribution that they did? What does this tell you about the content you are studying and your understanding of the world? And how does this theory fit into the overall course? These reflective questions are quite difficult to answer, but they can be used to help you develop a fascination and interest in the topic(s) that you are studying. Lecturers spend a lot of time thinking about their course or unit and developing content, so very little information is chosen by accident.

While being active and immersing yourself in the course are two effective ways of getting close to the content, you need to remember to cater for the person you are by making continual adjustments. If you are unable to attend every class, how might you address this? Are you the type of person who will read the readings in advance, or do you tend to be less organised? Do you daydream? Do you ask questions when you need to follow up? All of these aspects can be catered for and worked on, but it will take recognition, time, and effort. Practice self-compassion while you do what will no doubt be some uncomfortable things in the name of learning and growth.

Rate your proficiency levels for each of these skills (beginner/intermediate/advanced). There are helpful steps to help you enhance each still you rate.

1. Building positive relationships. Rating: (beginner/intermediate/advanced)

Steps to Enhance:

- Engage in active listening during conversations.

- Participate in group activities or study groups.

- Seek opportunities for mentorship and collaboration.

2. Task management. Rating: (beginner/intermediate/advanced)

Steps to Enhance:

- Use a planner or digital tool to record deadlines.

- Break down larger tasks into smaller steps.

- Set clear goals and timelines for each task.

3. Self-Management. Rating: (beginner/intermediate/advanced)

Steps to Enhance:

- Develop a routine that includes breaks and self-care.

- Set realistic and achievable personal goals.

- Practice mindfulness or meditation to help manage stress.

4. Time management. Rating: (beginner/intermediate/advanced)

Steps to Enhance:

- Create a weekly schedule that includes study, work and leisure time.

- Identify time wasting activities and work to reduce them.

- Set specific time blocks for focused study without distractions.

5. Research. Rating: (beginner/intermediate/advanced)

Steps to Enhance:

- Familiarise yourself with academic databases and research tools.

- Check sources for relevance and peer review.

- Develop a systematic approach to note taking and organising your information.

6. Collaboration. Rating: (beginner/intermediate/advanced)

Steps to Enhance:

- Be open to participate in group projects and contribute to the group.

- Practice open and respectful communication with others.

- Develop skills in conflict resolution and negotiation.

7. Flexibility. Rating: (beginner/intermediate/advanced)

Steps to Enhance:

- Embrace change and seek opportunities for growth.

- Developing coping strategies for handling unexpected challenges.

- Reflect on past experiences of change and identity lessons that you have learned.

8. Problem solving. Rating: (beginner/intermediate/advanced)

Steps to Enhance:

- Practice breaking down complex problems into smaller components.

- Explore multiple solutions before deciding on the best approach.

- Reflect on problem-solving successes and areas of improvement.

9. Self-Reflection. Rating: (beginner/intermediate/advanced)

Steps to Enhance:

- Set aside time for self-reflection and journaling.

- Seek feedback from peers and lecturers on your progress and growth.

- Use self-reflection to inform your personal and academic development plans.

Use your response to these skills to plan for your development. You may be able to think of additional skills that you would also like to develop.

3.5 Productive struggle

To put it simply, learning is uncomfortable, but it is also an exciting challenge. The discomfort you experience while learning is the pain of personal growth, as new skills and knowledge change what you can do, how you see the world, and how you understand yourself. Not knowing what you are talking about or whether you truly understand something can be anxiety-provoking, but struggling with content is an important part of learning, especially at university. Grappling with ideas by discussing, asking and answering questions is generally known as ‘productive struggle’, and it is not only inevitable when studying at university, it is often desirable. Being comfortable with being uncomfortable is the key here. Spending time in the in-between state of not knowing and knowing is something that every student needs to develop a tolerance for. The research takes this one step further to talk about the “pedagogy[1] of discomfort”. The pedagogy of discomfort highlights the changes in emotional states (from curiosity to frustration or from interest to boredom for instance) while learning (Mills & Creedy, 2021). Sometimes this emotional state can be because the learning is challenging your biases (as can be seen in the study by Mills & Creedy, 2021), and sometimes it can be your own impatience with the learning process. But there are a few things you can do to engage better in productive struggle.

Now that you understand your strengths and areas of improvement better, try to be more transparent about the challenges you are going to face. Being aware of how difficult something is going to be will help you to maintain a positive or growth mindset toward the task at hand. Developing a growth mindset and reminding yourself that you do not understand ‘yet’ is also helpful when engaging in productive struggle. Allow yourself time to persevere and take a break when you feel yourself becoming frustrated. Understanding yourself and how you usually react here will help you to predict your emotional reaction before it becomes a problem, making you more efficient and helping you feel more positive about your learning and progress. Discuss your thinking process with others and really listen to the ways that they interpret what you are saying. Asking specific questions on what you do not understand will help you better discuss the content while meeting your learning needs. Essentially, you learn the most when you are challenged or feel discomfort.

Engaging in productive struggle and embracing the discomfort will develop your tolerance for uncomfortable situations and thinking. Many of your lecturers who conduct research will experience this almost daily, so it could be worth talking about it directly with your lecturer.

3.6 Weeding in the rain

Developing your skills as a learner is often compared with the care we take growing a garden. This is a great metaphor as it emphasises the patience required, the joy in seeing things bloom, and, perhaps most importantly, the time it takes to grow. Giving your garden the right amount of water, sun, and fertiliser will allow it to grow into something amazing. Too much sun and not enough water will dry it out which is very similar to trying to work without enough rest or play. Some soil is harder to grow in than others, so extra attention and care are needed to ensure that you are giving the plants (skills) the best chance at success. Again, this is very similar to our experiences and challenges when trying to learn. But the real test to your resilience is when you are forced to try to develop your skills when the conditions are not the best. Life will happen while you are trying to study, which can make it hard to focus on skill development. To continue the metaphor, if it is raining outside, will you spend time weeding your garden? Studies have shown that the most resilient people tend to focus on looking after themselves when things become more difficult, whereas less resilient people will start to drop many of the things they do for self-care. It turns out that weeding in the rain is not just a metaphor for looking after yourself and your skills when things get difficult, it is an important skill of resilience that ensures that you can continue to learn and grow.

A word of caution: while it is true that continuous improvement is an important aspect of attending university, make sure you pause occasionally to reflect and celebrate the successes of your achievements. This chapter is intended to break you out of a fixed mindset towards a compassionate understanding of skill growth. It is not intended for you to replace one difficult habit (thinking of yourself as fixed, broken, or unable to grow) with another (thinking of yourself as never good enough and constantly searching for the perfect student with no respite). Experiment and enjoy the process, but do not let it become an obsession.

3.7 Key strategies from this chapter

- Recognise strengths and weaknesses: Reflect on feedback from others and adopt a growth mindset to identify areas for improvement.

- Challenge fixed perceptions: Move away from seeing skills as unchangeable by understanding that all abilities can be developed.

- Manage tasks effectively: Break tasks into smaller steps, use planners, and focus on the skills required.

- Embrace productive struggle: Learn to embrace discomfort in learning by realising that it is part of the process.

- Increase academic engagement: Prepare for classes, engage in discussions, and explore the course or unit materials to deepen your academic engagement.

- Celebrate growth: Acknowledge your progress and take breaks to ensure learning is sustainable.

3.8 Chapter summary

In this chapter, we have:

- developed an understanding of the self as a learner by focusing on growth rather than fixed abilities.

- understood that strengths and areas of improvement are not static and can be developed over time with reflection and effort.

- discussed how effective learning begins with productive struggle and embracing discomfort.

- examined the concept that managing tasks, the self, and fostering positive relationships can help develop an understanding of academic demands.

3.9 Reflection questions

- How do you currently perceive your strengths and areas of improvement as a learner? How might these perceptions influence your approach to studying?

- How do you typically respond to feedback from others? What strategies could you use to make feedback more constructive for your learning process?

- In what ways can you adapt a growth mindset to help you approach your learning and growth in a more positive way?

- Reflect on your current approach to managing academic tasks. What changes could you make to improve your task management and overall academic performance?

- How do you react to challenges and discomfort in your learning process? What steps can you take to better tolerate and utilise productive struggle?

References

Closs, L., Mahat, M., & Imms, W. (2022). Learning environments’ influence on students’ learning experience in an Australian Faculty of Business and Economics. Learning Environments Research, 25(1), 271-285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-021-09361-2

Frost-Camilleri, L. (2021). It is time to let go of learning styles. Fine Print, 44(3), 3-7.

Mills, K., & Creedy, D. (2021). The ‘pedagogy of discomfort’: A qualitative exploration of non-indigenous student learning in a First Peoples health course. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 50(1), 29-37. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2019.16

Nancekivell, S., Shah, P., & Gelman, S. (2020). Maybe they’re born with it, or maybe it’s experience: Toward a deeper understanding of the learning style myth. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(2), 221-235. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000366

Waite, C., Walsh, L., & Black, R. (2023). Negotiating senses of belonging and identity across education spaces. The Australian Educational Researcher, 50(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-023-00633-9

I would love to hear your thoughts on this chapter, share your feedback.

- Pedagogy is a teaching term which means ‘the method and practice of teaching’. ↵